Abstract

We study immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment in Sweden combining population-wide register data and a unique survey targeting a large representative sample of the total population of long-term self-employment. Using the registers, we analyze the evolution of labor and capital incomes during the first 10 years following self-employment entry. We find that immigrant-native differences in labor income become smaller, whereas immigrant-native differences in capital income grow stronger, over the course of self-employment. These findings are robust to controlling for factors such as organizational form and type of industry. We use the survey data to gain further insights into immigrant-native differences among the long-term self-employed, and show that immigrant self-employed experience more problems and earn less, but work harder than native self-employed. They also have a less personal relation to their customers, do not enjoy their work as much as natives, and appear to have different perspectives on self-employment in general.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research regarding immigrant-native differences in self-employment rates has been conducted in several OECD counties.Footnote 1 Besides mapping immigrant-native differences in self-employment rates, much attention has been paid to identify the determinants behind the self-employment entry decision among different groups of immigrants. Studies from different countries have shown that factors such as family traditions, home-country traditions, and the existence of ethnic enclaves, as well as discrimination in the wage-employment sector, are important determinants behind the self-employment entry decision among certain immigrant groups.Footnote 2 However, despite the relatively large amount of research that has focused on immigrant-native differences in self-employment, and despite the fact that certain immigrant groups have higher exit rates from self-employment, less is known about the extent to which there are immigrant-native differences among individuals who remain self-employed over the years, i.e., if there are immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment.

In this paper, we aim to fill this knowledge gap by conducting a study in which we compare different economic outcomes for foreign- and native-born individuals who have been self-employed for a spell of 10 years or more in Sweden. Since the share of self-employed immigrants has increased in several countries over the years, and since self-employment often has been viewed as a way for immigrants who have problems in entering the labor market to escape poverty and unemployment, it is important to increase our understanding of how self-employed immigrants perform in the long run. Sweden is a suitable country for a study of long-term outcomes of self-employed immigrants since it is a country with a relatively long history of immigration and a country that also has experienced a large increase in self-employment among foreign-born individuals during the past 30 years.

Our study is conducted with the help of a combination of high-quality Swedish register data and a unique survey designed specifically for this paper. From the register data, we obtain information about demographic background factors such as age, educational attainment, and the family situation of individuals. We also obtain information about labor and capital income. The survey, which targeted foreign-born individuals as well as native-born Swedes with long-term experience from self-employment, allows us to obtain answers to questions that cannot be addressed using register data. The questions in the survey depart from results and experiences from previous research regarding immigrant self-employment, and aim to further increase our understanding regarding the success factors and obstacles self-employed immigrants encounter in their businesses. By combining register and survey data, we are able to paint a detailed picture of the background factors that characterize long-term self-employed natives and immigrants, as well as analyze what factors these individuals themselves consider to be the most important for their self-employment experience.

Throughout the paper, we define immigrants as foreign-born individuals. We further divide the foreign-born population by region of birth, separating between European and non-European immigrants. This is due to the fact that research has shown that non-European immigrants, more often than European immigrants, suffer from low earnings and high rates of unemployment and are over-represented in the self-employment sector.Footnote 3

We arrive at several interesting results. Our register analysis shows that, over the course of the first decade of self-employment experience, immigrant-native differences in labor income become smaller over time, whereas immigrant-native differences in capital income grow stronger. These findings are robust to controlling for factors such as organizational form and type of industry. The survey results show that self-employed immigrants experience more problems and earn less, but work harder. They also have a less personal relation to their customers, do not enjoy their work as much as natives, and appear to have different perspectives on self-employment in general.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 below, we provide a brief discussion of Swedish immigration history and the composition of migration to Sweden during the last decades. Section 3 describes the register and survey data that we use in our analysis. In Section 4, we present an analysis of immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment outcomes based on Swedish population registers, using a combination of graphical and regression analyses. In Section 5, we analyze our survey targeted at the long-term self-employed which allows us to obtain insights into the factors explaining the outcome differences documented in Section 4. Finally, Section 6 offers concluding remarks.

2 Immigration to Sweden

Sweden has experienced a relatively extensive immigration during the decades after World War II. However, the characteristics of this immigration have changed over time.Footnote 4 During the end of the 1940s, immigration to Sweden consisted primarily of refugees from Eastern Europe. In the 1950s, labor force migration reached significant proportions as a result of the industrial and economic expansion. The labor force migration peaked during the 1950s and 1960s, with the influx of immigrants coming predominantly from Sweden’s neighbors (e.g., Finland) and from countries in Western and Southern Europe (e.g., Italy, Greece, West Germany, Yugoslavia).

From the 1970s and onwards, immigration to Sweden has consisted primarily of refugee immigrants and “tied movers” or relatives of already admitted immigrants. In the 1970s, refugee migration from Latin America increased, while during the 1980s, many refugees came from Africa and the Middle East.

Migration from Europe increased temporarily again during the early 1990s. This involved refugees fleeing the civil war in former Yugoslavia. Since the mid-1990s, most of the immigrants to Sweden have been refugees from countries in and around the Middle East and Africa. During the 2000s, immigration to Sweden reached historically high numbers, peaking during the years 2015 and 2016 with a large influx of refugees from Syria, Iraq, and also other countries in the Middle East and Africa.

As of 2020, about 20% of Sweden’s total population is foreign-born. The change from labor force migration to refugee migration has transformed the composition of the country’s immigrant population. During recent decades, the share of immigrants born outside Europe has grown markedly, and today, around 55% of the foreign-born population originates from countries outside Europe, with Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Somalia being the dominant countries.Footnote 5

3 Data and institutional setting

3.1 Register data

The register data that we use in the paper consist of Swedish linked employer-employee data combined with administrative data from the Swedish tax authority. The data cover the period 2002 to 2016 and is longitudinal, enabling us to follow individuals over time. The data include information on sector of employment, labor, and capital income, as well as socio-economic and demographic information, such as educational attainment and immigration status.Footnote 6

Throughout the paper, we define natives as those born in Sweden and immigrants as those who are born outside of Sweden. Hence, in our paper, immigrants correspond to first-generation immigrants. Using information on birth region, we further classify immigrants into European and non-European immigrants. The motivation behind this classification is that previous research has shown that non-European immigrants typically are considered to have a disadvantage in the Swedish labor market and are over-represented in the self-employment sector. These patterns are not unique to Sweden, and can be found in many other European countries.Footnote 7

We define a person as self-employed if his/her main source of income are self-employment activities.Footnote 8 To analyze long-term self-employment outcomes, our register analysis focuses on self-employment spells that began between 2002 and 2006.Footnote 9 This allows us to follow individuals for at least 10 years. In principle, we could include earlier self-employment experiences into our analysis, but we choose the relatively narrow interval 2002–2006 in order to focus on businesses that develop during roughly the same point in time and hence face roughly the same business climate and macroeconomic conditions. Furthermore, this ensures that the sample used in the analysis based on register data matches the survey data. The data allow us to distinguish between incorporated and unincorporated business owners, as well as to identify people who are wage-employed. In our analysis, we restrict our attention to individuals aged 20 to 64 and exclude self-employed individuals in the agricultural sector.

To compare self-employment performance between immigrants and natives, we focus on annual taxable labor and capital income from the tax administration. These are the two main sources of economic compensation to individuals and are tightly connected to individual well-being. Labor income represents the sum of the employment income from wage and business activities, minus a general deduction. The capital income variable includes interest income from savings, and dividend income from stocks and ownership in closely held corporations.Footnote 10

Figure 1 shows the fraction of people in our sample who stay self-employed for at least T years, where T = 0,...,10 and T = 0 corresponds to the year of self-employment entry. From the figure, we observe that the share who remain in self-employment is higher among natives than among European and non-European immigrants. Ten years after self-employment entry, around 40% of natives are still self-employed, whereas for European immigrants, the corresponding share is somewhat lower. Among non-European immigrants, on the other hand, the corresponding share is 30%.Footnote 11

Our focus is on immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment. We therefore focus on individuals who became self-employed in 2002–2006 and remained in self-employment for at least ten consecutive years. These individuals are defined as long-term self-employed in our paper and correspond to those who are still in the sample at T = 10 in Fig. 1. In total, the sample includes 54,486, 4089, and 3095 self-employed natives, European immigrants, and non-European immigrants, respectively.

Our register-based analysis will be divided into two parts. We will first graphically analyze how taxable labor and capital income evolve over the first 10 years following self-employment entry. We will then estimate, in a regression framework, the effect of immigrant background on these outcome measures, averaged over these 10 years. The purpose of analyzing the effect of immigrant background on these ten year averages is to approximate “permanent” income measures for the long-term self-employed.

Table 1 below shows summary statistics for our final sample.Footnote 12 The first thing to notice is that, on average, self-employed natives have both higher labor and capital income than self-employed European and non-European immigrants. In terms of individual characteristics at the year of self-employment entry, we find that on average, European immigrants are older, and non-European immigrants are younger than their native counterparts. For all groups, the majority of the self-employed are male, with the fraction being the largest among non-European immigrants and smallest among European immigrants. Non-European immigrants are on average the least educated and European immigrants are the most educated. In addition, as compared to natives and European immigrants, non-European immigrants are more likely to be married and more likely to have children under the age of 18 living at home.

In terms of business characteristics, around half of native self-employed individuals start an incorporated business, whereas only around 14% of self-employed non-European immigrants do so.Footnote 13 Furthermore, we find that about 44% of non-European immigrants start businesses in industries with low barriers to entry while the corresponding share among natives and European immigrants is only around 20%.Footnote 14

3.2 Survey data

A key aspect of our contribution is that we combine a register analysis for the total population, with the results from a tailor-made, register-linked survey that enables us to learn about the factors that native and immigrant entrepreneurs themselves consider to be important for their long-term self-employment experience.

The survey was designed uniquely for this paper and was conducted in collaboration with Statistics Sweden between September 2018 and January 2019. It targeted a random sample of the total population of self-employed in Sweden who had been self-employed for ten consecutive years between 2007 and 2016 (we exclude the self-employed in the agricultural sector).Footnote 15 A total of around 17,500 survey questionnaires were sent out by regular mail and the response rate was around 40%, corresponding to around 7000 respondents. Among the respondents, the shares of natives, and European and non-European immigrants were about 41, 34, and 25%, respectively.Footnote 16

We selected the survey questions based on results from previous research regarding self-employment and immigrant self-employment.Footnote 17 To understand the nature of the businesses of the self-employed in our sample, we asked different questions about their self-employment experience, and the characteristics of their firms. It is well known that social and entrepreneurial networks, educational attainment, and access to financial capital are of central importance for the possibility to become and succeed as self-employed, and that the importance of these factors may vary between immigrants and natives (see, for example, Blanchflower & Oswald 1998; Blanchard et al., 2008). We therefore asked the respondents how important they perceived that these factors have been for their self-employment activities. Furthermore, it is well known that immigrants may encounter other problems than natives in their firms (see, for example, Constant & Zimmermann 2006; Aldén & Hammarstedt2016). We therefore asked the respondents about perceived success factors and perceived obstacles in their self-employment activities. Table 18 in Appendix B presents the full set of survey questions.

To assess the representativeness of our survey data, Table 2 presents descriptive statistics where we compare the survey respondents and the population data from which the survey was drawn.Footnote 18 The table shows that the survey sample and the corresponding population data from which the survey was sampled are overall quite similar in terms of average characteristics. The only clear exceptions are that non-European immigrants in the survey data are more likely to be college educated than non-European immigrants in the population data (40% versus 26%) and are also more likely to be female (27% versus 18%).Footnote 19

Comparing the characteristics of natives and immigrants within the group of survey respondents, we find that the share of women is about 30% for both natives and immigrants. The average age in the year 2016 is about 56, 57, and 54 for natives, and European and non-European immigrants, respectively. Among the survey respondents, both natives and immigrants seem to have similar education levels. Non-European immigrants are more likely to be married and more likely to have children under the age of 18 at home than the other groups. Furthermore, among self-employed non-European immigrants, the share of individuals with an incorporated business is much smaller and the share of individuals working in industries with low barriers to entry is much higher, relative to natives and European immigrants. In terms of income, we find that self-employed natives have on average a much higher disposable income than both European and non-European immigrants.Footnote 20

4 Economic outcomes for the long-term self-employed: evidence from Swedish registers

4.1 Graphical evidence

We begin with a graphical analysis where we, for different immigrant groups, explore how measures of self-employment performance evolve during the first 10 years following self-employment entry.

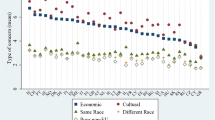

In Fig. 2, we analyze the evolution of labor income, focusing on yearly population averages as well as the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles. Similar to Fig. 1, T = 0 corresponds to the year of self-employment entry (which is potentially different for each individual).

The figure shows that there is a sizable gap between natives and immigrants, especially in the case of non-European immigrants. The gap decreases with self-employment experience, but a noticeable difference is evident even after 10 years in self-employment. The fact that all the graphs are upwards sloping likely reflects the fact that many businesses grow over time, and therefore generate an increasing stream of income to their owners. We can also see that the gap between natives and immigrants diminishes over time. As time goes by, immigrants become more and more integrated into society (e.g., by learning language skills) and are therefore able to achieve business incomes that are more similar to those of natives.

Figure 3 shows the trajectories for capital income. The figure in the left panel shows capital income trajectories in a graph similar to the first panel of Fig. 2. The perhaps most interesting observation is that, in contrast to the evolution of labor income, we find that the gap in terms of capital income between self-employed natives and non-European immigrants, widens over time. Thus, when it comes to capital income, non-European immigrants do not seem to catch up in the same way as in Fig. 2. The gap between natives and European immigrants is on the other hand quite small, at least when looking at average outcomes. Since a sizable share of individuals earn zero capital income, the right panel of Fig. 3 shows the share of positive (non-zero) capital income among natives and immigrants. The figure shows that the share of individuals with positive capital income increases for both natives and immigrants over the course of self-employment. However, even after a long time in self-employment, e.g., at T = 10, less than 50% of non-European immigrants earn a positive capital income.

In Fig. 4, we analyze the evolution of the distribution of capital income among the self-employed with positive capital income by inspecting the evolution of different percentiles. We observe a clear, widening gap between natives and immigrants in the top quartile of the distribution, in particular between natives and non-European immigrants.

In the analysis so far, we have not considered that natives and immigrants run different types of firms with respect to corporate form and type of industry. Figure 5 therefore shows the share of self-employed who have an incorporated business (left panel) and the share who work in industries with low barriers to entry (right panel), and how these variables evolve over time. We see that the fraction of non-European immigrants who have an incorporated business is very low. The share at T = 0 is about 15% among non-European immigrants, while the corresponding shares for natives and European immigrants are about 35% and 50%, respectively. However, the extent of incorporation increases over time in all immigrant groups, but there is no pattern of convergence or divergence across immigrant groups.Footnote 21 About half of non-European immigrants work in industries with low barriers to entry, whereas the share is only about 20% for natives and European immigrants. Furthermore, it does not seem that long-term entrepreneurs change industries during the first 10 years following self-employment entry. There is a small tendency for European immigrants to leave industries with low barriers of entry, but, overall, the likelihood of moving between low- and high-entry barrier industries is low for both natives and immigrants during the first 10 years.

In Appendix A, motivated by the immigrant-native differences documented in Fig. 5, we re-do Figs. 2 and 4 based on whether an individual starts an incorporated business or not at the time of self-employment entry (see Appendix Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11) and based on whether an individual starts a firm in a low barrier-to-entry industry or not (see Appendix Figs. 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). These results show that capital income is generally much higher among those who start an incorporated business and those who start a business in an industry that does not classify as an industry with low barriers to entry. However, independently of the corporate form and type of industry at the time of self-employment entry, the immigrant-native gap in labor income seems to converge over time, whereas the immigrant-native gap in capital income seems to widen over time.Footnote 22

One reason for the stronger growth of capital income among natives could be that natives run businesses that are more likely to generate capital income to their owners as the businesses grow. Another explanation could be that self-employed natives are better at obtaining a larger share of their self-employment compensation in the form of capital income, which is beneficial due to the typically lower marginal tax rate on capital income in the context of the Swedish dual-income tax system (where the taxation of capital income is separated from the taxation of labor income).Footnote 23

Finally, we have repeated Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5 where we compare natives with immigrants, dividing up the analysis depending on if these immigrants arrived to Sweden before or after (or in) 1990. These figures can be found in Figs. 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, and 32 in the Appendix and show that cohorts that arrived to Sweden before 1990 generally have a more positive long-term development of labor and capital income relative to more recent cohorts, especially among European immigrants.

4.2 Regression evidence

We now turn to a regression approach to examine immigrant-native differences in average labor income and capital income over the course of self-employment. The benefit of the regression approach is that we can control for a set of individual characteristics at the year of self-employment entry. We focus on the following specification:

The outcome variable \(\log Y_{i}\) is the logarithm of individual average income over the period T = 0 to T = 10. The purpose of focusing on 10-year averages is to approximate a “permanent” income measure for the long-term self-employed. Xi represents a vector of control variables, including age, gender, marital status, education, and the number of children in the household under age 18, and 𝜖i is an error term. The variables of interest are the dummies Europeani and NonEuropeani that indicate whether a self-employed person is a European or a non-European immigrant, with the reference group being self-employed natives. The estimates of the coefficients β and γ capture immigrant-native difference in average earnings.

Table 3 presents the estimated coefficients of interest for each outcome variable, with and without controls.Footnote 24 The results in specification (2), with controls, show that, relative to natives, average labor income is about 24% lower for European immigrants and about 41% lower for non-European immigrants. Mirroring the graphical evidence, the largest immigrant-native differences are found for capital income, which is around 60% lower for European immigrants and around 90% lower for non-European immigrants.Footnote 25 The average income gap between immigrants and natives may not fully reflect how the gap looks like in different parts of the outcome distribution. Therefore, in Table 12 in Appendix B, we re-run the above specification using quantile regression. For both labor and capital income, the results show that the earnings gap is largest in the bottom of the distribution (at the 25th percentile) and smallest at the top of the distribution (at the 75th percentile).

Notice that the longitudinal nature of the data also allows us to perform a traditional panel data analysis. However, the major advantage of using 10-year averages is that this approximates a measure of permanent long-term income for the long-term self-employed in our sample. This cross-sectional approach also allows us to smooth out year-specific fluctuations in labor and capital income, which is especially important in the case of capital income, due to the volatile nature of capital income flows. However, as a robustness check, we have also performed a traditional panel data analysis in Table 16 in Appendix B. This analysis confirms the large immigrant-native differences in both labor and capital incomes.Footnote 26

Figure 5 showed that there are large immigrant-native differences in terms of the likelihood to have an incorporated firm and the likelihood to have a firm in an industry with low barriers to entry. It is therefore interesting to estimate the earnings gap when splitting the sample along these dimensions. Table 4 shows that for both labor income and capital income, the earnings gap between self-employed natives and immigrants remains large when restricting the analysis to either individuals with the same corporate form or to individuals who operate in industries with similar barriers to entry. However, the immigrant-native gap is larger among self-employed with unincorporated firms and firms in industries with low barriers to entry.

One key element for the success of self-employment activities is country-specific human capital which is accumulated by immigrants by spending time in the host country. In our sample, at the time of self-employment entry, European immigrants have stayed in Sweden for about 20 years and non-European immigrants have stayed in Sweden for about 14 years. Thus, the two immigrant groups differ not only in terms of their country of birth, but also in terms of their length of exposure to the host country.Footnote 27 Table 5 repeats the analysis in Table 3 dividing up the analysis depending on the length of stay in Sweden at the time of self-employment entry. The results show that for both European and non-European immigrants, the estimated income differences relative to natives decrease with respect to the duration of stay in the host country. The results suggest that country-specific human capital at the time of self-employment entry can have a long-run impact on business performance and earnings.Footnote 28 However, it is important to note that there are substantial differences among natives and immigrants, even among those who have stayed a very long time in Sweden before they start their business, especially in the case of non-European immigrants.

Of course, those who have stayed in Sweden for a long time naturally also belong to earlier cohorts of immigrant to Sweden. To shed further light on the role of immigration cohort, Table 6 presents a table similar to Table 5 that divides up the results depending on if the self-employed individual migrated to Sweden before or after 1990.Footnote 29 The results confirm the pattern observed in the graphical evidence, namely, that cohorts that arrived to Sweden before 1990 generally have better long-term outcomes. In fact, European immigrants who arrived before 1990 have long-term outcomes that are very similar to natives.

4.3 Discussion

The previous literature has found that native self-employed in general have better economic outcomes than immigrant self-employed along a number of economic dimensions. This literature has mainly focused on the choice to become self-employed and short-run self-employment outcomes. Our contribution is to take a long-term perspective, and also analyze important immigrant-native differences in the evolution of capital income along the course of self-employment.

Our graphical analysis showed that labor earnings for long-term self-employed natives and immigrants appear to converge over time, while capital income appears to be widening over time. Moreover, a regression analysis of long-run averages revealed that a substantial immigrant-native gap persists, even after controlling for different factors at the time of self-employment entry. The gap is more pronounced among those with unincorporated businesses, and the widest gap is found when comparing natives and non-European immigrants, and when considering immigrants with a shorter duration of stay in Sweden at the time of self-employment entry or immigrants who arrived more recently to Sweden.

It is well-known that non-European immigrants have difficulties in the Swedish and many European labor markets. Hence, non-European immigrants are more likely than natives to be pushed into the self-employment sector. This is also partly reflected in our results that show that a large number of non-European self-employed immigrants are working in low entry barrier sectors and choose to pursue their business activity in unincorporated firms. However, substantial immigrant-native differences remain even when we restrict attention to those who start the same type of business in the same type of industry. To obtain further insights into the determinants of these remaining differences, we turn to analyze our survey targeting the long-term self-employed.

5 Survey evidence

We now turn to our survey evidence. Section 5.1 starts by describing the background characteristics of the long-term self-employed individuals in our sample. The purpose is to understand what characterizes long-term self-employed individuals along background dimensions that are typically not available in register data, with a focus on highlighting immigrant-native differences.Footnote 30 We then proceed to analyze the more specific questions of our survey, which fall into two broad categories: factors that contribute to long-term self-employment and self-employment success (Section 5.2) and obstacles facing the long-term self-employed (Section 5.3).Footnote 31

5.1 Background characteristics

Table 7 describes the background characteristics of our survey respondents, focusing on individual and family characteristics, business characteristics, language skills, working hours, and perspectives on self-employment. The first three columns show the mean value for each variable for natives, and European and non-European immigrants. The subsequent two columns test for statistically significant differences between each of the two immigrant groups and the native reference group.

We begin by noticing that the average age at self- employment entry is significantly higher among immigrants than that among natives. This holds true especially for non-European immigrants. An interesting question is whether there are immigrant-native differences in the inter-generational transmission of the choice to become self-employed and what role the family plays for the long-term self-employed.Footnote 32 We find that immigrants are in general less likely to have parents who are self-employed.Footnote 33 This could reflect that immigrants are pushed into self-employment due to lack of better alternatives rather than being pulled into self-employment, by, for instance, family traditions. We also find that non-European immigrants are less likely than natives to have family members or relatives work in their business.

Turning to business characteristics, we find that immigrant-owned businesses are on all accounts much more likely to interact with people with a foreign background, in the form of either employee relationships, or relationship with suppliers or customers.Footnote 34 The difference relative to natives is strongest for non-European immigrants. Furthermore, compared with non-European immigrants, natives report to be more likely to have a personal relationship with their customers.

Language skills are obviously very important for immigrants to succeed in the labor market. However, it is unclear to which extent language skills play a role for the long-term self-employed and whether there are differences between immigrant groups. We find that compared to natives, non-European immigrants are about 40 percentage points less likely to be proficient in Swedish while the corresponding difference between European immigrants and natives is only about 17 percentage points. We also note that non-European immigrants are also less likely to be highly proficient in English compared to natives and European immigrants.

Regarding hours of work, we find no differences in terms of hours of work between natives and European immigrants. However, non-European immigrants work much more, on average almost five more hours per week. This is despite the fact that non-European immigrants, on average, generally earn much less than natives. The proportion of individuals among the long-term self-employed who have another job is however small among both natives and immigrants.Footnote 35 We also see that among those who report that their partner works in their business, immigrants report that their partner works longer hours than natives do, especially in the case of non-European immigrants. Thus, a clear message is that non-European long-term self-employed immigrants, and their partners, work much more than their native and European counterparts.

A specific purpose of the survey was to go beyond the traditional monetary measures of self-employment success to obtain a broader view of immigrant-native differences in self-employment success. In particular, we asked respondents whether they enjoy being self-employed, whether they instead would have preferred to be employed as a regular employee, whether they consider themselves to have achieved their goals as self-employed and whether they think that they will be self-employed five years into the future. What we find is that the attitude towards self-employment differs dramatically among self-employed natives and immigrants, even though we focus on individuals who all share a long history of self-employment. Compared to natives, immigrants consider self-employment to be less enjoyable, would rather be wage employed, and to a lesser extent feel that they have achieved their goals. This is line with the common explanation that many immigrants are pushed into self-employment due to the lack of better labor market opportunities. Interestingly, immigrants also feel, to a much greater extent than natives, that luck is more important than hard work for economic success.

To sum up, we find large immigrant-native differences in several important dimensions. The most striking ones are those that relate to working hours and perspectives on self-employment.

5.2 Perceived success factors

Table 8 analyzes how the respondents view different factors that could be important in explaining their long-term success in self-employment. The questions focus on the role of the family, social networks, work experience, and access to capital.

Between 25 and 30% of respondents perceive their partner to be important for the success of their business. Non-Europeans consider their partners to be the most important and the difference relative to natives is statistically significant. Children are considered to be less important in general, with only about 11 to 13% of respondents considering them to be important for the success of their business. There is a small tendency for non-European immigrants to consider children to be more important, but the difference relative to the other groups is not statistically significant. Relatives are considered to be less important than both partners and children, but here there is still a clear immigrant-native difference, with around 10% of non-European immigrants considering children to be important for the success of their business, whereas the corresponding share for natives is only around 6%.

Previous literature has found that social networks are important not only in the startup phase of a business, but also for its long-term performance. Our survey shows that former employers and colleagues are important for both self-employed natives and immigrants, but natives value them much more, especially compared to non-European immigrants. Previous business partners appear however to be roughly equally important to immigrants and natives, with around 20% of respondents expressing that such connections are important for their business. Interestingly, a significantly higher share of self-employed non-European immigrants consider previous classmates, neighbors, and friends to be important. The answers to the questions of the importance of the social network suggest that there are potentially large immigrant-native differences in terms of how important networks outside the workplace are considered for the success in self-employment.Footnote 36 The fact that primarily non-European immigrants seem to, relative to natives and European immigrants, lack social networks with a strong connection to the labor market, could be one explanation for their worse long-term self-employment outcomes.

An important question is to which extent human capital acquired in the home country is transferable to the new host country as individuals migrate and to which extent education acquired in the host country is perceived as valuable for the success in self-employment. Both European and non-European immigrants consider their education in their home country to be valuable, with no clear differences between the two groups of immigrants. Most respondents also consider having an education in the host country (Sweden) to be an important advantage. The shares are 55 and 63%, respectively for European and non-European immigrants, which should be compared to the share among natives, which is 68%. Regarding past work experience in the Swedish labor market, about 60% of natives, 59% of European immigrants, and 55% of non-European immigrants find this factor to be important. Overall, and quite naturally, we see that natives value education and working experience more than immigrants. This is one explanation behind the the fact that a significant proportion of self-employed non-European immigrants work in industries with low barriers to entry, where the human capital requirements are smaller.

Previous research has found that natives and immigrants differ in terms of their ability to obtain capital to fund the startup and growth of their businesses.Footnote 37 From Table 8, we see that both self-employed natives and immigrants consider bank loans to be an important source of capital, although European immigrants weight the importance less than natives. Furthermore, we find that immigrants, particularly non-European immigrants, are more likely to consider other sources of finance, to be important.

5.3 Perceived obstacles

Our survey contained several questions with the purpose of identifying immigrant-native differences in terms of how respondents perceive and rank the importance of different obstacles to self-employment success. The results are shown in Table 9. Overall, we find that non-European immigrants experience more obstacles than natives do. In particular, they perceive high taxes, high salaries, access to capital, tax complexity, and finding appropriate employees to be more of a problem relative to natives, and often also in comparison to European immigrants.

Our results show that high taxes and tax complexity are perceived to be, relative to natives, more problematic among non-European immigrants but not among European immigrants. One natural potential explanation for this is that non-European immigrants are less familiar with European tax systems that share many common features. The immigrant-native divergence in the perceptions about taxes can have important implications since governments often use tax policy to stimulate entrepreneurship. If there are immigrant-native differences in terms of the understanding of the host country’s tax system (which some research seems to indicate is the case; see e.g., Bastani et al., 2020), such measures can potentially exacerbate the immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment outcomes that we have documented in this paper.Footnote 38 We also see that that self-employed non-European immigrants have more difficulties in finding employees. This can be due to several factors, such as ethnically segregated hiring networks or ethnic preferences among employees (see, e.g., Giuliano et al., 2009).

6 Concluding remarks

We have studied immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment using a combination of administrative population registers and a unique survey targeting a large representative sample of self-employed immigrants and natives.

Our register analysis has placed a special emphasis on the evolution of labor and capital incomes during the first 10 years following self-employment entry, and suggests that natives are more successful than non-European immigrants along key dimensions in the sense of having a stronger evolution of labor income, and a much sharper increase in capital income, over the course of self-employment. The only exception to this pattern are self-employed individuals with incorporated firms, where we find small immigrant-native differences in the top of the distribution of labor and capital income. Furthermore, while immigrant-native differences in labor income, on average, seem to converge over the course of self-employment, there is no such convergence for capital income. When analyzing 10-year averages of individuals’ labor income and capital income trajectories in a regression framework, we find that substantial long-term immigrant-native differences remain, even after controlling for several factors at the point of self-employment entry.

Our survey data allowed us to obtain insights into what can explain these differences, and gain further insights into the role of immigrant background for long-term self-employment outcomes. The results show that self-employed immigrants experience more problems and earn less, but work harder than self-employed natives. They also have a less personal relation to their customers, do not enjoy their work as much as natives, and appear to have different perspectives on self-employment in general. Finally, while self-employed natives have a stronger network of former employers and colleagues, self-employed immigrants more often rely on help from their family and relatives in their self-employment activities.

To date, much of the academic and policy discussion have focused on immigrant-native differences in the decision to become self-employed and short-run self-employment outcomes. This discussion has highlighted important immigrant-native differences in the success of self-employment activities, and has also highlighted the fact that natives and immigrants face different obstacles and have different motives for becoming self-employed. We confirm the importance of the factors highlighted in this discussion, but we also add new knowledge to the research area regarding immigrant self-employment, and we conclude that the immigrant-native differences in self-employment activities often documented in previous research also exist when we take a long-term perspective on this issue.

Notes

Studies have been conducted in the USA (see, e.g., Borjas (1986), Yuengert (1995), Fairlie and Meyer (1996), Fairlie (1999), Hout and Rosen (2000), Fairlie and Robb (2007b) and Robb and Fairlie (2009)) and in Australia (see Le (2000)), as well as in different European countries (see e.g., Clark and Drinkwater (2000) and Clark et al. (2017) for studies from the UK, Constant and Zimmermann (2006) for a study from Germany, and Hammarstedt (2001) for a study of Sweden).

The interested reader is referred to Boguslaw (2012) who presents a detailed description and discussion of Sweden’s immigration history.

Detailed information about the ethnic composition of the Swedish population can be found at Statistics Sweden, www.scb.se.

The variable educational attainment measures the highest obtained education. For foreign-born individuals with education acquired abroad, the variable is based on self-reported information.

In many European countries, non-European immigrants have a higher rate of self-employment than natives, such as in the UK, Finland, Belgium, and Hungary (OECD, 2017).

The measurement of sector of employment is made in November each year, and the definition of self-employment used in the paper corresponds to the definition used by Statistics Sweden.

We define an entry into self-employment if an individual was not self-employed in the previous year.

Table 17 provides a detailed description of all variables.

Notice that entrepreneurial exit is not equal to failure, as discussed by DeTienne (2010).

Notice that the final sample corresponds to those who are still in our sample at T = 10. In Appendix Table 15, we show the average characteristics of all individuals who started a business between 2002 and 2006, and the patterns look similar.

Levine and Rubinstein (2017) show that incorporated business owners in the USA tend to be both more educated and have stronger non-routine cognitive abilities than unincorporated business owners. Furthermore, their results suggest that the choice of corporate form mostly reflects the ex ante nature of the business, not the ex post performance. In addition, previous literature has shown that, due to tax incentives, high-income people are more likely to incorporate their business relative to low-income earners in Sweden (Edmark and Gordon, 2013). We present summary statistics separately for corporate and non-corporate business owners in Table 10 in the Appendix.

Our classification follows Lofstrom and Bates (2013) who identify industries with low barriers to entry using Swedish industry codes at a 2-digit level. The industries with low barriers to entry are mainly composed of personal services (excluding professional business services), transportation, and retail.

Notice that our register analysis and survey analysis are based on slightly different samples. The survey targeted all individuals who were self employed for 10 consecutive years between 2007 and 2016, whereas the register sample focuses on all those who started a business between 2002 and 2006 and who were then self-employed for at least ten consecutive years. The reason for this discrepancy is that we wish to have as large of a sample as possible when conducting the register analysis to allow to investigate subgroup differences.

The survey sample was stratified based on gender and region of birth (Sweden, Europe, the Middle East, and other non-European countries). In total, eight strata (2 × 4) were created and a random sample of 3000 individuals was drawn for each strata. For the strata of men and women born in the Middle East and other non-European countries, the population size was smaller than 3000. Hence, in these cases, the survey targeted the total population. In the analysis, we have merged the Middle East and other non-European countries into one category.

In addition, we gathered feedback on the survey from Almi Kronoberg, a local chapter of a state-owned organization that offers financing and support to native and immigrant entrepreneurs in Sweden.

We also compare the survey respondents and non-respondents in Appendix Table 11.

Notice that the register data described in Section 3.1, and the population data described for reference purposes in Table 2 are not the same, as they cover slightly different time periods. For this reason, the label referring to columns (4)–(5) in Table 2 is ”Survey population data” to distinguish it from the population data used in the register analysis.

When analyzing the survey data, we use disposable income as a proxy for the sum of labor and capital income since Statistics Sweden did not provide us with taxable labor and capital income data in the set of register variables connected to the survey data set.

In 2010, there was a reform that lowered the minimum financial capital required to start an incorporated business from 100,000 SEK to 50,000 SEK. Given that in our sample, all individuals started their business in 2002–2006, the reform might have induced some people to switch to an incorporated business 4–8 years after self-employment entry. We see a small tendency for the extent of incorporation to be somewhat higher among non-European immigrants (who are more likely to be capital constrained) during these years.

The only exception is the case of European immigrants, where we find that the labor income trajectories at the 50th and 75th percentiles are almost identical to those of natives for self-employed with incorporated firms (see appendix Fig. 6).

The reason could be immigrant-native differences in knowledge about the tax system, in line with the results of Bastani et al. (2020) who document important immigrant-native differences in tax filing even among individuals with relatively high incomes.

We exclude individuals who have zero capital income throughout the 10-year period. As a result, 3, 11, and 24% of natives, and European and non-European immigrants, respectively, are excluded from the analysis.

The distributions of length of stay in Sweden at the time of self-employment entry for the two immigrant groups are shown in Fig. 18 in Appendix A. We further present the evolution of labor and capital incomes for immigrants with different lengths of stay in Sweden at the time of self-employment entry in Figs. 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24 in Appendix A.

The level of education at the time of self-employment entry is also likely to be important. Table 14 in the Appendix analyzes earnings differences between natives and immigrants for different levels of education at the time of self-employment entry. Interestingly, the estimated interaction effects between the immigration dummies and the dummies for higher education are negative, indicating that the immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment outcomes are larger among those who have higher education. A limitation of these results is that we can only observe the quantity and not the quality of education. In particular, we can not observe whether immigrants have obtained their higher education in Sweden or in their home country. Another aspect is that there is likely to be a higher mismatch among highly educated immigrants between their level of education and the type of businesses that they run, in relation to natives.

The year 1990 can be motivated based on the discussion in Section 2.

As in the register analysis, our focus in the survey analysis is on first-generation immigrants.

An important study on the role of the family for business outcomes is Fairlie and Robb (2007a) who found that the success of small business owners was only weakly correlated with having a self-employed family member, but strongly correlated with prior work experience in a family member’s business.

This is in contrast to what has been found for second- and third-generation immigrants in Sweden; see Andersson and Hammarstedt (2010).

However, non-European immigrants who do have a job on the side also tend to work more hours on this job as well.

Kerr and Mandorff (2015) have shown that non-work relationships facilitate the acquisition of sector-specific skills and represent one important factor contributing to immigrant-native patterns in entrepreneurship.

For example, one particular complex part of the tax system facing self-employed individuals who contemplate incorporating their business is the corporation tax. Da Rin et al. (2011) have shown that the corporate income tax affects both the self-employment entry decision and the characteristics of the entering firms. There can also be a relationship between immigrant-native differences in the sensitivity to personal income taxation and immigrant-native differences in the decision to incorporate the business due to the possibility for tax planning with the context of the Swedish dual income tax system (see Alstadsæter & Jacob 2016 for an overview of income shifting in Sweden).

References

Aldén, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2016). Discrimination in the credit market? Access to financial capital among self-employed immigrants. Kyklos, 69(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12101.

Aldén, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2017). Egenföretagande bland utrikes födda: En översikt av utvecklingen under 2000-talet. Arbetsmarknadsekonomiska rå,det – Underlagsrapport, 1/2017.

Alstadsæter, A., & Jacob, M. (2016). Dividend taxes and income shifting. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 118(4), 693–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12148.

Andersson, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2010). Intergenerational transmissions in immigrant self-employment: Evidence from three generations. Small Business Economics, 34(3), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9117-y.

Andersson, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2015). Ethnic enclaves, networks and self-employment among Middle Eastern immigrants in Sweden. International Migration, 53(6), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2011.00714.x.

Asiedu, E., Freeman, J.A., & Nti-Addae, A. (2012). Access to credit by small businesses: How relevant are race, ethnicity, and gender?. American Economic Review, 102(3), 532–37. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.102.3.532.

Åslund, O., Hensvik, L., & Skans, O.N. (2014). Seeking similarity: How immigrants and natives manage in the labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(3), 405–441. https://doi.org/10.1086/674985.

Bastani, S., Giebe, T., & Miao, C. (2020). Ethnicity and tax filing behavior. Journal of Urban Economics, 103215, 116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2019.103215.

Blanchard, L., Zhao, B., & Yinger, J. (2008). Do lenders discriminate against minority and woman entrepreneurs? Journal of Urban Economics, 63(2), 467–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2007.03.001.

Blanchflower, D.G., & Oswald, A.J. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur?. Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/209881.

Boguslaw, J. (2012). Svensk invandringspolitik under 500 år: 1512–2012. Studentlitteratur.

Borjas, G.J. (1986). The self-employment experience of immigrants. Journal of Human Resources, 21(4), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.2307/145764.

Clark, K., & Drinkwater, S. (2000). Pushed out or pulled in? Self-employment among ethnic minorities in England and Wales. Labour Economics, 7(5), 603–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00015-4.

Clark, K., & Drinkwater, S. (2002). Enclaves, neighbourhood effects and employment outcomes: Ethnic minorities in England and Wales. Journal of Population Economics, 15(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00003839.

Clark, K., Drinkwater, S., & Robinson, C. (2017). Self-employment amongst migrant groups: New evidence from England and Wales. Small Business Economics, 48(4), 1047–1069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9804-z.

Constant, A., & Zimmermann, K.F. (2006). The making of entrepreneurs in germany: Are native men and immigrants alike? Small Business Economics, 26(3), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-3004-6.

Da Rin, M., Di Giacomo, M., & Sembenelli, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship, firm entry, and the taxation of corporate income: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Public Economics, 95(9-10), 1048–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.06.010.

DeTienne, D.R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25 (2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.004.

Edmark, K., & Gordon, R.H. (2013). The choice of organizational form by closely-held firms in Sweden: Tax versus non-tax determinants. Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(1), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dts045.

Ek, S., Hammarstedt, M., & Skedinger, P. (2020). Enkla jobb och kunskaper i svenska – Nycklar till integration? SNS-förlag.

Fairlie, R.W. (1999). The absence of the African-American owned business: An analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(1), 80–108. https://doi.org/10.1086/209914.

Fairlie, R.W., & Meyer, B.D. (1996). Ethnic and racial self-employment differences and possible explanations. Journal of Human Resources, 31(4), 757–793. https://doi.org/10.2307/146146.

Fairlie, R.W., & Robb, A.M. (2007a). Families, human capital, and small business: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. ILR Review, 60(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390706000204.

Fairlie, R.W., & Robb, A.M. (2007b). Why are black-owned businesses less successful than white-owned businesses? The role of families, inheritances, and business human capital. Journal of Labor Economics, 25(2), 289–323. https://doi.org/10.1086/510763.

Giuliano, L., Levine, D.I., & Leonard, J. (2009). Manager race and the race of new hires. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(4), 589–631. https://doi.org/10.1086/605946.

Hammarstedt, M. (2001). Immigrant self-employment in Sweden-its variation and some possible determinants. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 13(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620010004106.

Hammarstedt, M., & Miao, C. (2020). Self-employed immigrants and their employees: Evidence from Swedish employer-employee data. Review of Economics of the Household, 18(1), 35–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-019-09446-1.

Hammarstedt, M., & Shukur, G. (2009). Testing the home-country self-employment hypothesis on immigrants in Sweden. Applied Economics Letters, 16(7), 745–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850701221907.

Hout, M., & Rosen, H. (2000). Self-employment, family background, and race. Journal of Human Resources, 35(4), 670–692. https://doi.org/10.2307/146367.

Kerr, W.R., & Mandorff, M. (2015). Social networks, ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Le, A.T. (2000). The determinants of immigrant self-employment in Australia. International Migration Review, 34(1), 183–214. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676017.

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 963–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw044.

Lofstrom, M., & Bates, T. (2013). African Americans’ pursuit of self-employment. Small Business Economics, 40(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9347-2.

OECD. (2017). Immigrants’ self-employment and entrepreneurship activities.

Robb, A.M., & Fairlie, R.W. (2009). Determinants of business success: An examination of Asian-owned businesses in the USA. Journal of Population Economics, 22(4), 827–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0193-8.

Yuengert, A.M. (1995). Testing hypotheses of immigrant self-employment. Journal of Human Resources, 30(1), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.2307/146196.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. The data that support the findings of this study are provided by Statistics Sweden and are covered by secrecy, but the anonymized microdata can be accessed following a confidentiality assessment, provided that Statistics Sweden considers that the researcher has the grounds to process the data (see https://www.scb.se/en/services/guidance-for-researchersand-universities/ for more information). In addition, one has to to apply for permission from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (https://etikprovningsmyndigheten.se/). The authors are willing to assist in the process of obtaining the data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University. Financial support was received from Familjen Kamprads Stiftelse.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Appendix figures

Appendix B: Appendix tables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aldén, L., Bastani, S., Hammarstedt, M. et al. Immigrant-native differences in long-term self-employment. Small Bus Econ 58, 1661–1697 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00462-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00462-z