Abstract

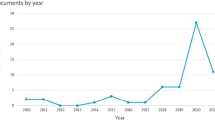

This paper focuses on women’s entrepreneurship policy as a core component of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. We use a systematic literature review (SLR) approach to critically explore the policy implications of women’s entrepreneurship research according to gender perspective: feminist empiricism, feminist standpoint theory, and post-structuralist feminist theory. Our research question asks whether there is a link between the nature of policy implications and the different theoretical perspectives adopted, and whether scholars’ policy implications have changed as the field of women’s entrepreneurship research has developed. We concentrate on empirical studies published in the “Big Five” primary entrepreneurship research journals (SBE, ETP, JBV, JSBM, and ERD) over a period of more than 30 years (1983–2015). We find that policy implications from women’s entrepreneurship research are mostly vague, conservative, and center on identifying skills gaps in women entrepreneurs that need to be “fixed,” thus isolating and individualizing any perceived problem. Despite an increase in the number of articles offering policy implications, we find little variance in the types of policy implications being offered by scholars, regardless of the particular theoretical perspective adopted, and no notable change over our 30-year review period. Recommendations to improve the entrepreneurial ecosystem for women from a policy perspective are offered, and avenues for future research are identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Small Business Economics (SBE), Entrepreneurship, Theory, and Practice (ETP), Journal of Business Venturing (JBV), Journal of Small Business Management (JSBM), Entrepreneurship and Regional Development (ERD).

We considered including other leading journals, books, and conference papers, but given the considerable qualitative analysis involved in our methodological approach and the inevitable increased volume of material, we felt such inclusions would be beyond that which would be manageable within a single journal paper.

References

Acker, J. (2008). Feminist theory’s unfinished business: comment on Andersen. Gender and Society, 22(1), 104–108.

Acs, Z., Astebro, T., Audretsch, D., & Robinson, D. (2016). Public policy to promote entrepreneurship: a call to arms. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 35–51.

Acs, Z., Bardasi, E., Estrin, S., & Svejnar, J. (2011). Introduction to special issue of small business economics on female entrepreneurship in developed and developing economies. Small Business Economics, 37, 393–396.

Ahl, H. (2004). The scientific reproduction of gender inequality: a discourse analysis of research texts on women's entrepreneurship. Copenhagen: CBS Press.

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 595–621.

Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2012). Exploring the dynamics of gender, feminism and entrepreneurship: advancing debate to escape a dead end? Organization, 19(5), 543–565.

Ahl, H., & Nelson, T. (2015). How policy positions women entrepreneurs: a comparative analysis of state discourse in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 273–291.

Aldrich, H. E., & Martinez, M. A. (2001). Many are called but few are chosen: an evolutionary perspective for the study of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(4), 41–56.

Alsos, G., Isaksen, E. J., & Ljunggren, E. (2006). New venture financing and subsequent business growth in men- and women-led businesses. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 667–686.

Anna, A. N., Chandler, G. N., Jansen, E., & Mero, N. P. (2000). Women business owners in traditional and non-traditional industries. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(3), 279–303.

Bartunek, J. M., & Rynes, S. (2010). The construction and contributions of 'Implications for practice: what’s in them and what might they offer? Academy of Management Learning and Education, 9(1), 100–117.

Bird, B., & Brush, C. (2002). A gendered perspective on organizational creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(3), 41–65.

Black, N. (1989). Social feminism. New York: Cornell University Press.

Brush, C. G. (1992). Research on women business owners: past trends, a new perspective and future directions. Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, 16(4), 5–30.

Calas, M. B., & Smircich, L. (1996). The woman’s point of view: feminist approaches to organization studies. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of organization studies (pp. 218–257). London: Sage Publications.

Campbell, R., & Wasco, S. M. (2000). Feminist approaches to social science: epistemological and methodological tenets. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 773–791.

Carter, N. M., & Allen, K. R. (1997). Size determinants of women-owned businesses: choice or barriers to resources? Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 9(3), 211–220.

Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2011). Institutions and female entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 37, 397–415.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1990). Small business formation by unemployed and employed workers. Small Business Economics, 2(4), 319–330.

Fischer, E. M., Reuber, R. A., & Dyke, L. S. (1993). A theoretical overview and extension of research on sex, gender and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 151–168.

Foss, L., & Gibson, D. V. (Eds.). (2015). The entrepreneurial university. Context and institutional change. London: Routledge.

GEM—Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2015) Special report—women’s entrepreneurship. Available from: http://www.babson.edu/Academics/centers/blank-center/global-research/gem/Documents/GEM%202015%20Womens%20Report.pdf. Accessed 3 August 2016.

Gicheva, D., & Link, A. E. (2015). The gender gap in federal and private support for entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 45, 729–733.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Grimaldi, R., Kenney, M., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2011). 30 years after the Bayh-Dole: reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40, 1045–1057.

Gupta, V. K., Goktan, A. B., & Gunay, G. (2014). Gender differences in evaluation of new business opportunity: a stereotype threat perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 273–288.

Harding, S. (Ed.). (1987). Feminism and methodology. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Henry, C., Foss, L., & Ahl, H. (2016). Gender and entrepreneurship: a review of methodological approaches. International Small Business Journal, 34(3), 217–241.

Holmes, M. (2007). What is gender? London: Sage.

Hooks, B. (2000). Feminist theory: from margin to center: Pluto Press.

Isenberg, D. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–51.

Jayawarna, D., Rouse, J., & Macpherson, A. (2014). Life course pathways to business start-up. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(3–4), 282–312.

Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? The Academy of Management Annals, 7, 661–713.

Kalleberg, A. L., & Leicht, K. T. (1991). Gender and organizational performance: determinants of small business survival and success. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 136–161.

Kalnins, A., & Williams, M. (2014). When do female-owned businesses out-survive male-owned businesses? A disaggregated approach by industry and geography. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(6), 822–835.

Kantis, H. D., & Federico, J. (2012). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in Latin America: the role of policies. Liverpool: International Research and Policy Roundtable (Kauffman Foundation).

Katz, J. A. (2003). The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrepreneurship education 1876–1999. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 283–300.

Klyver, K., Nielsen, S. L., & Evald, M. R. (2013). Women's self-employment: an act of institutional (dis)integration? A multilevel, cross-country study. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 474–488.

Kvidal, T., & Ljunggren, E. (2014). Introducing gender in a policy programme: a multilevel analysis of an innovation policy programme. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32, 39–53.

Link, A. N., & Strong, D. R. (2016). Gender and entrepreneurship: an annotated bibliography. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 12(4–5), 287–441.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1984). The postmodern condition: a report on knowledge (Vol. 10). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Manolova, T., Varter, N. M., Manev, I. M., & Gyoshev, B. S. (2007). The differential effect of men and women entrepreneurs' human capital and networking on growth expectancies in Bulgaria. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 407–426.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth-oriented enterprises. OECD LEED programme. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Entrepreneurial-ecosystems.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2015.

Mazzarol, T. (2014). Growing and sustaining entrepreneurial ecosystems: what they are and the role of government policy. Seaanz, Australia: Seaanz White Paper.

McAdam, M. (2013). Female entrepreneurship. London/New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Mendez-Picazo, M. T., Galindo-Martin, M. A., & Riberio-Soriano, D. (2012). Governance, entrepreneurship and economic growth. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 24(9/10), 865–877.

Moore, J. F. (1996). The death of competition: leadership and strategy in the age of business ecosystems. New York: Harper Business.

Mukhtar, S. M. (2002). Differences in male and female management characteristics: a study of owner-manager businesses. Small Business Economics, 18(4), 289–310.

Neergaard, H., Frederiksen, S. H., Marlow, S. (2011). The emperor’s new clothes: rendering a feminist theory of entrepreneurship visible. Paper to the 56th ICSB Conference, June 15-18, Stockholm.

Nilsson, P. (1997). Business counselling services directed towards female entrepreneurs—some legitimacy dilemmas. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 9(3), 239–258.

Orser, B. J., Riding, A. L., & Manley, K. (2006). Women entrepreneurs and financial capital. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 643–665.

Pittaway, L., & Cope, J. (2007). Entrepreneurship education. A systematic review of the evidence. International Small Business Journal, 25(5), 479–510.

Roomi, M. A. (2013). Entrepreneurial capital, social values and cultural traditions: exploring the growth of women-owned enterprises in Pakistan. International Small Business Journal, 31, 175–191.

Rosa, P., & Dawson, A. (2006). Gender and the commercialization of university science: academic founders of spinout companies. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development: An International Journal, 18(4), 344–366.

Scherer, R. F., Brodzinsky, J. D., & Wiebe, F. A. (1990). Entrepreneur career selection and gender: a socialization approach. Journal of Small Business Management, 28(2), 37–43.

Scott, R. W. (2014). Institutions and organizations: ideas, interest, and identities (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Shneor, R., Metin Camgöz, S., & Bayhan Karapinar, P. (2013). The interaction between culture and sex in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(9–10), 781–803.

Spiegel, B. (2015). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12167

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769.

Steffens, P. R., Weeks, C. S., Davidsson, P., & Isaak, L. (2014). Shouting from the ivory tower: a marketing approach to improve communication of academic research to entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 399–426.

Steyaert, C. (2011). Entrepreneurship as in(ter)vention. Reconsidering the conceptual politics of method in entrepreneurship studies. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23(1), 77–88.

Tranfield, D. R., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14, 207–222.

Tylor, E. B. (1974). Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art and custom. New York: Gordon Press.

Van De Ven, H. (1993). The development of an infrastructure for entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(3), 211–230.

Verhul, I., Uhlaner, L., & Thurik, R. (2005). Business accomplishments, gender and entrepreneurial self-image. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(4), 483–518.

WEF—World Economic Forum. (2013) Entrepreneurial ecosystems around the globe and company growth dynamics: report summary for the annual meeting of the new champions 2013,” Switzerland: WEF, September, available from: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_EntrepreneurialEcosystems_Report_2013.pdflast accessed 20th November 2015.

Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship—conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 35(1), 165–184.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing Gender. Gender and Society, 1, 125–151.

Wicker, A. W., & King, J. C. (1989). Employment, ownership, and survival in microbusiness: a study of new retail and service establishments. Small Business Economics, 1(2), 137–152.

Zahra, S. A. (2007). Contextualizing theory building in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(3), 443–452.

Zahra, S. A., & Nambisan, S. (2012). Entrepreneurship and strategic thinking in business ecosystems. Business Horizon, 55, 219–229.

Zahra, S. A., & Wright, M. (2011). Entrepreneurship’s next act. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(4), 67–83.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Stages in the SLR process

Stage | Description |

|---|---|

1 | A list of the “Big Five” journals in entrepreneurship research was compiled: ERD, ETP, JBV, JSBM, SBEa. |

2 | Each member of the author team was allocated a discrete 10-year period to search: period 1: 1983–1992; period 2: 1993–2002; period 3: initially 2003–2012 and subsequently updated to include the period up to end December 2015. |

3 | Within journal searches were conducted by means of a systematic Boolean keyword search using the terms “gender” OR “women” OR “woman” OR female AND “entrepreneur” OR entrepreneurship OR “business” in the title, keywords, and abstract field. We used the academic Scopus database to perform our search. This database covers all the journals in our SLR. As a cross check, in some cases, content pages of each journal issue/volume were examined to ensure no relevant paper was omitted/missed. |

4 | The resulting articles were then examined, and exclusion criteria were applied. Discussions between the authors throughout the process ensured that any further potential exclusions were discussed and agreed. In this step, we excluded 50 papers in the last (updated) period and 39 papers in the three first periods. This resulted in a total of 165 papers. |

5 | The common thematic reading guide designed by authors was then applied |

6 | The author team discussed articles as they reviewed them to ensure consistency of analysis. |

Appendix 2: Reading guide

SLR reading guide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Article title | ||||

2. Author(s) | ||||

3. Year of publication | ||||

4 Journal | ||||

5.Feminist perspectives | Perspectives | Explicit (x) | Implicit (x) | Comments |

FE | ☐ | ☐ | ||

FST | ☐ | ☐ | ||

PSF | ☐ | ☐ | ||

Other | ☐ | ☐ | ||

6. Feminist perspective key findings/notes | ||||

7a. Policy implications | Yes (x) ☐ No (x) ☐ | |||

7b. If yes in 7a. How are the policy implications being reported in the paper | Explicit ☐ Implicit ☐ | Policy implication findings /quotes/notes: | ||

7c: If yes in 7a. Definition of policy implications: | Yes ☐ If yes Explain: No ☐ | |||

How do they address the implications: | ||||

8a. Other implications reported? | ☐ Future entrepreneurs ☐ Nascent entrepreneurs ☐ Education ☐ Female business owners ☐ Financial capital providers ☐ Researchers ☐ Managers ☐ Others…………………………………………….. | |||

8b: Practical implication text: | ||||

9a. Ecosystem code | ☐P = Policya ☐F = Funding and finance ☐C = Culture ☐M = Mentors ☐U = Universities as catalyst ☐E = Education ☐H = Human capital and workforce ☐L = Local and global markets ☐NO = No implications for ecosystem | |||

9b. Ecosystem explanations (beside policy implications): | ||||

10a. Type of implications for future research | ☐ Entrepreneurship research ☐ Gender research ☐ Other: …………. ☐ No implications | |||

10b. If yes in 10a. Implication text: | ||||

11. Sample size n: | ||||

12. Country: | ||||

Appendix 3. Logistic regression

We formulated H1: There is a significant relationship between policy implications in articles and feminist perspectives applied. Given the binary nature of the dependent variable, we conducted a binary logistic regression with feminist perspectives as explanatory variables and policy implication as the binary dependent variable. The dependent variable is coded 1 for articles with policy implications and 0 for those with no policy implications. The feminist perspectives are used as the independent variables, all coded as dummy variables. The feminist perspective “other theoretical perspective” containing only three cases was removed from the analyses since there was no variation in this variable. All three of these cases where coded “policy implication.” To ensure we accounted for all the variability in our SLR data, we controlled for other observations collected in our SLR, such as geographical area, time periods and specific type of implication, and type of journal, all coded as dummy variables.

1.1 Results

Categories | Variables | Policy implication | |

|---|---|---|---|

Coefficienta (std. error) | Wald χ2 | ||

Feminist perspectives | Post-structural feminism | – | 3.39 |

Feminist empiricism | 1.023 (0.73) | 1.94 | |

Feminist standpoint theory | 0.190 (0.76) | 0.06 | |

Journals | SBE | – | 6.07 |

JSBM | 1.134 (0.70) | 2.64 | |

ETP | − 0.240 (0.70) | 0.12 | |

ERD | − 0.286 (0.71) | 0.16 | |

JBV | 0.342 (0.70) | 0.24 | |

Area | Asia + Africa | – | 1.02 |

Europe | 0.371 (0.68) | 0.29 | |

America | − 0.149 (0.63) | 0.05 | |

Time | 1982–1993 | – | 15.57 |

1993–2002 | 1.643 (0.57) * | 8.11 | |

2003–2015 | 2.472 (0.63) ** | 15.21 | |

Practical implications | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 1.454 (0.43) ** | 11.51 |

Constant | − 2.454 (1.2) ** | 3.75 | |

Model diagnostic | |||

N | 162 | ||

− 2 log likelihood | 158.00 | ||

Cox and Snell R2 | 0.213 | ||

Nagelkerke R2 | 0.303 | ||

Model χ2 | 38.892 ** | ||

df | 11 | ||

Hosmer and Lemeshow χ2 | 8.002 (p = 0.433) | ||

Overall % correct prediction | 76.1% | ||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Foss, L., Henry, C., Ahl, H. et al. Women’s entrepreneurship policy research: a 30-year review of the evidence. Small Bus Econ 53, 409–429 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9993-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9993-8

Keywords

- Women’s entrepreneurship

- Ecosystem

- Policy implications

- Gender research

- Systematic literature review (SLR)