Abstract

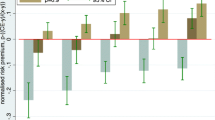

Risk aversion—but also the higher-order risk preferences of prudence and temperance—are fundamental concepts in the study of economic decision making. We propose a method to jointly measure the intensity of risk aversion, prudence, and temperance. Our theoretical approach is to define risk compensations of different orders, and in an experiment we elicit these compensations with a price list technique. We find evidence for risk aversion, prudence, and temperance. These traits correlate within subjects. The compensations elicited for prudence are significantly larger than those for risk aversion and temperance. In contrast to commonly used utility functions, prospect theory can predict this behavioral pattern. In our experiment, risk-averse, risk-loving, and risk-neutral subjects are prudent. This supports a recent theoretical observation that prudence may be a more universal trait than previously realized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Deck and Schlesinger (2010) are the first to provide an intuitive, qualitative discussion on the issue. They analyze in what direction probability weighting, reference dependence, and loss aversion influence preference among the risk apportionment lottery pairs in their experiment. They also compute the prospect theory values of their lotteries for the estimates of Tversky and Kahneman (1992).

Eeckhoudt and Schlesinger (2006) originally considered the lotteries \(\tilde {B}_2=0\) and \(\tilde {A}_2=[0,\tilde {\epsilon }],\) where \(\tilde {\epsilon }\) is a zero-mean risk, and show that preferring \(\tilde {B}_2\) over \(\tilde {A}_2\) for all \(\tilde {\epsilon }\) is equivalent to u ′′ < 0. We use the lotteries B 2 and A 2 to avoid experimental certainty effects.

Many different compensations or premia are possible. For example, the (second-order) risk premium defined in Ross (1981) corresponds to an amount subtracted from B 2 for sure in our setting. Crainich and Eeckhoudt (2008) define a prudence compensation similar to ours that is subtracted in the good state of A 3 only. We have chosen the compensation that, we think, is most convenient for experimentation; see Section 2.3 for a discussion. It has been termed “compensating risk compensation” in Pope and Chavas (1985), and Kimball (1990) considers a “compensating precautionary compensation” in the context of prudence. The earliest analysis of this compensation we are aware of is LaValle (1968). Pratt (1964) briefly mentioned that this compensation relates to the “bid price,” while his “equivalent premium” relates to the “ask price” of a risk.

The corresponding intervals in stage PR is also (−5,5) for all three tasks, while in stage TE they are (−3.5,3.5) and (−2.8,2.8) for tasks TE1 and TE2, respectively. Therefore, in stage TE this caveat is less pronounced.

Aggregated over six tasks, 85% of individuals switched once and 8% did not switch. That is, 93% of subjects never violated transitivity. For 3% we observe two switches, and in about 4% of responses subjects switch back and forth more than two times. This latter fraction is slightly lower than reported in other price list experiments to elicit risk preferences. Holt and Laury (2002), for example, report between 5 to 6% of multiple switches.

We do so simply because the observations for the six task compensations are similar and because comparisons of six compensations throughout would be cumbersome. Nevertheless, for the interested reader we collect further results on the task compensations in Section C of the web appendix. One result on task level we would like to highlight concerns the impact of differently skewed zero-mean risks \(\tilde {\epsilon }_1\) employed in tasks PR1, PR2, and PR3. Similar to Ebert and Wiesen (2011), we find some support for “stronger prudence” when \(\tilde {\epsilon }_1\) is more left-skewed. Ebert (2012) provides a theoretical analysis of this result.

Ebert and Wiesen (2011), Noussair et al. (2014), and Deck and Schlesinger (forthcoming) do not observe gender differences when testing for prudence, and only Noussair et al. find that women are more temperate. Deck and Schlesinger (2010) and Maier and Rüger (2011) do not report any gender-related results.

For the functional forms of these utility classes see Section E of the web appendix. Analogously to the empirical stage compensations \(\overline {\hat {m}}^{\overline {\text {\tiny PR}}}\) and \(\overline {\hat {m}}^{\overline {\text {\tiny TE}}},\) the predicted stage compensations mPR and mTE are the means of the predicted task compensations in stage PR and TE, respectively.

For a risk averter who prefers more to less, sure reductions in wealth are “bad” and zero-mean risks are also “bad.” For a risk lover who prefers more to less, sure reductions in wealth are “bad” but zero-mean risks are “good.”

Risk lovers are those subjects that demanded a negative compensation in stage RA whereas risk-averse (risk-neutral) subjects demanded a positive (zero) compensation in stage RA.

References

Abdellaoui, M. (2000). Parameter-free elicitation of utility and probability weighting functions. Management Science, 46, 1497–1512.

Abdellaoui, M., Driouchi, A., L’Haridon, O. (2011). Risk aversion elicitation: Reconciling tractability and bias minimization. Theory and Decision, 71, 63–80.

Baillon, A. (2013). Prudence (and more) with respect to uncertainty and ambiguity. Working paper.

Barberis, N. (2012). A model of casino gambling. Management Science, 58, 35–51.

Barsky, R.B., Kimball, M.S., Juster, F.T., Shapiro, M.D. (1997). Preference parameters and behavioral heterogeneity: An experimental approach in the health and retirement study. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 537–579.

Becker, G., DeGroot, M., Marschak, J. (1964). Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behavioral Science, 9, 226–232.

Bostian, A.J., & Heinzel, C. (2012). Prudential saving: Evidence from a laboratory experiment. Working paper, University of Virgina.

Caballé, J., & Pomansky, A. (1996). Mixed risk aversion. Journal of Economic Theory, 71, 485–513.

Carrol, C.D. (1994). How does future income affect current consumption? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 111–147.

Carroll, C.D., & Kimball, M.S. (2008). Precautionary savings and precautionary wealth. In S. Durlauf & L. Blume (Eds.) The new palgrave dictionary of economics, (pp. 579–584). MacMillan.

Crainich, D., & Eeckhoudt, L. (2008). On the intensity of downside risk aversion. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 36, 267–276.

Crainich, D., Eeckhoudt, L., Trannoy, A. (2013). Even (mixed) risk lovers are prudent. American Economic Review, 104, 1529–1535.

Croson, R.T.A., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 448–474.

Deck, C., & Schlesinger, H. (2010). Exploring higher order risk effects. Review of Economic Studies, 77, 1403–1420.

Deck, C., & Schlesinger, H. (forthcoming). Consistency of higher-order risk preferences. Econometrica.

Dittmar, R.F. (2002). Nonlinear pricing kernels, kurtosis preference, and evidence from a cross section of equity returns. Journal of Finance, 57, 369–403.

Dynan, K.E. (1993). How prudent are consumers? Journal of Political Economy, 101, 1104–1013.

Ebert, S. (2012). Skewed background risks. Working paper, University of Bonn.

Ebert, S. (2013). Even (mixed) risk lovers are prudent: Comment. American Economic Review, 103, 1536–1537.

Ebert, S., & Wiesen, D. (2011). Testing for prudence and skewness seeking. Management Science, 57, 1334–1349.

Ebert, S., & Wiesen, D. (2013). Web appendix to joint measurement of risk aversion, prudence, and temperance, available at: https://sites.google.com/site/ebertecon/research.

Eckel, C.C., & Grossman, P.J. (2008). Forecasting risk attitudes: An experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 68, 1–17.

Eeckhoudt, L., & Gollier, C. (2005). The impact of prudence on optimal prevention. Economic Theory, 26, 989–994.

Eeckhoudt, L., Gollier, C., Schlesinger, H. (1996). Changes in background risk and risk taking behavior. Econometrica, 64, 683–689.

Eeckhoudt, L., & Schlesinger, H. (2006). Putting risk in its proper place. American Economic Review, 96, 280–289.

Eeckhoudt, L., & Schlesinger, H. (2008). Changes in risk and the demand for saving. Journal of Monetary Economics, 55, 1329–1336.

Eeckhoudt, L., Schlesinger, H., Tsetlin, I. (2009). Apportioning of risks via stochastic dominance. Journal of Economic Theory, 144, 994–1003.

Esö, P., & White, L. (2004). Precautionary bidding in auctions. Econometrica, 72, 77–92.

Fei, W., & Schlesinger, H. (2008). Precautionary insurance demand with state-dependent background risk. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 75, 1–16.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-tree: Zurich toolbox for readymade economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Franke, G., Schlesinger, H., Stapleton, R. (2011). Risk taking with additive and multiplicative background risks. Journal of Economic Theory, 146, 1547–1568.

Gomes, F., & Michaelides, A. (2005). Optimal life-cycle asset allocation: Understanding the empirical evidence. Journal of Finance, 60, 869–904.

Greiner, B. (2004). An online recruitment system for economic experiments In K. Kremer, & V. Macho (Eds.) Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen. Bericht 63, (pp. 79–93). Göttingen: Gesellschaft für wissenschaftliche Datenverarbeitung.

Grether, D.M., & Plott, C.R. (1979). Economic theory of choice and the preference reversal phenomenon. American Economic Review, 69, 623–638.

Guiso, L., Jappelli, T., Terlizzese, D. (1996). Income risk, borrowing constraints and portfolio choice. American Economic Review, 86, 158–172.

Holt, C.A., & Laury, S.K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92, 1644–1655.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–292.

Kimball, M.S. (1990). Precautionary savings in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 58, 53–73.

Kimball, M.S. (1992). Precautionary motives for holding assets. In P. Newman, M. Milgate, John Eatwell (Eds.) The new palgrave dictionary of money and finance, (pp. 158–161): Stockton Press.

Kocher, M., Pahlke, J., Trautmann, S. (2012). An experimental test of precautionary bidding. Working paper.

LaValle, I.H. (1968). On cash equivalents and information evaluation in decisions under uncertainty: Part I: Basic theory. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 63, 252–276.

Leland, H.E. (1968). Saving and uncertainty: The precautionary demand for saving. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 82, 465–473.

Maier, J., & Rüger, M. (2011). Experimental evidence on higher-order risk preferences with real monetary losses. Working Paper, University of Munich.

Menezes, C.F., Geiss, C., Tressler, J. (1980). Increasing downside risk. American Economic Review, 70, 921–932.

Menezes, C.F., & Wang, X.H. (2005). Increasing outer risk. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 41, 875–886.

Montgomery, D. (2005). Design and analysis of experiments. Wiley.

Noussair, C., Trautmann, S., van de Kuilen, G. (2014). Higher order risk attitudes, demographics, and financial decisions. Review of Economic Studies, 81(1), 325–355.

Pope, R., & Chavas, J. (1985). Producer surplus and risk. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 100, 853–869.

Pratt, J.W. (1964). Risk aversion in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 32, 122–136.

Ross, S. (1981). Some stronger measures of risk aversion in the small and in the large with applications. Econometrica, 49, 621–663.

Rothschild, M.D., & Stiglitz, J.E. (1970). Increasing risk: I. A definition. Journal of Economic Theory, 2, 225–243.

Saha, A. (1993). Expo-power utility: A flexible form for absolute and relative risk aversion. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 75, 905–913.

Sandmo, A. (1970). The effect of uncertainty on saving decisions. Review of Economic Studies, 37, 353–360.

Schubert, R., Brown, M., Gysler, M., Brachinger, H.W. (1999). Financial decision-making: Are women really more risk-averse? American Economic Review, 89, 381–385.

Stott, H. (2006). Cumulative prospect theory’s functional menagerie. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 32, 101–130.

Tarazona-Gomez, M. (2004). Are individuals prudent? An experimental approach using lottery choices. Working paper, Copenhagen Business School.

Treich, N. (2010). Risk-aversion and prudence in rent-seeking games. Public Choice, 145, 339–349.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

Wakker, P., & Deneffe, D. (1996). Eliciting von Neumann-Morgenstern utilities when probabilities are distorted or unknown. Management Science, 42, 1131–1150.

White, L. (2008). Prudence in bargaining: The effect of uncertainty on bargaining outcomes. Games and Economic Behavior, 62, 211–231.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for valuable comments and suggestions by Han Bleichrodt, Louis Eeckhoudt, Armin Falk, Thomas Gehrig, Holger Gerhardt, Glenn Harrison, Lorens Imhof, Harris Schlesinger, Reinhard Selten, anonymous referees, and the editor. We also thank conference participants of the 2012 ESEM (Malaga), 2011 ESA European Meeting (Luxembourg), the 2011 EEA (Oslo), the 2010 GfeW Meeting (Luxembourg), and the 2010 LMU Excellence Symposium in Munich. We further thank seminar participants in Bonn, Essen, Freiburg, Rotterdam, Tilburg, and participants of the Sino-German Summer School workshop in Bonn in January 2010. We thank Emanuel Castillo for his z-Tree programming assistance as well as Martin Acht and Javier Sanchez for their help with conducting the experiment. Christian Hilpert and Johannes Pfeifer provided very valuable consultation on Matlab programming. Furthermore, we thank Michael Borss, Mara Ewers, Stefanie Lehmann, Jan Meise, and Gert Pönitzsch for their participation in a pilot experiment and their helpful comments on the experiment at that stage. The experiment was financed through the Geneva Association Research Grant 2009. During their doctoral studies, Ebert received financial support from the Bonn Graduate School of Economics, and Wiesen from the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ebert, S., Wiesen, D. Joint measurement of risk aversion, prudence, and temperance. J Risk Uncertain 48, 231–252 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-014-9193-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-014-9193-0