Abstract

The notion of merit-aid is not a new development in higher education. Although previous researchers have demonstrated the impact of state-adopted merit-aid funding on student decision-making, fewer studies have examined institutional pricing responses to broad-based merit-aid policies. Using a generalized difference-in-difference approach, we extend previous empirical work by examining the impact of merit-aid on institutional pricing strategies while considering both the institution’s tuition-setting authority and the relative strength of the merit-aid program. In this study, we find that colleges and universities with the authority to set their own tuition increased their in-state tuition and fees following broad-based merit-aid policy adoption; however, institutions with state-controlled tuition-setting authority respond to broad-based merit-aid policies by lowering their in-state tuition and fees. Our findings suggest that the incentives and dynamics of each state’s policy environment are significant determinants of institutional responses to state-level policy adoptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Between 1993 and 2005, 14 states have offered merit aid to high-achieving resident students.

Long (2004) found that four-year institutions throughout Georgia increased their costs for attendance after the adoption of Georgia’s state-level merit-aid policy and effectively diluted the benefit of merit-aid. This study extends Long’s work in several substantive ways, as outlined in this paper.

As we discuss later, we define broad-based merit-aid as merit-aid policies that have large per-FTE subsidies and cover a substantial proportion of students enrolled at public 4-year institutions.

The majority of institutions removed were community colleges that were reclassified as public 4-year institutions due to their awarding of bachelor’s degrees. See Fulton (2015) for information on states implementing community college baccalaureate policies during our analytical period.

Missing data were concentrated primarily in institutions that have zero tuition reliance (i.e., service academies) and public 4-year institutions that reported no state appropriation revenue or FTE enrollment in a given year.

We omitted private institutions from our analysis because not all state merit-aid programs provide incentives for enrollment at private 4-year institutions. All state-adopted merit-aid programs provide financial support to qualified in-state students attending a public 4-year institution.

The practice of using the NASSGAP Survey to identify merit-aid policy adopters is rooted within the academic literature. Specifically, Doyle (2006) used it to classify adopters for his event history analysis as well as Fitzpatrick and Jones (2012) in their analysis of multi-state merit-aid adoption on student migration. Additionally, none of these states met the criteria for broad-based merit-aid policies, and thus would not impact our point estimates.

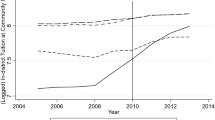

Figure 1 provides the pre- and post-adoption trends for each of our identified broad-based merit-aid states. Across each of our identified adopters, institutions within merit-aid states followed similar pre-adoption trends compared to institutions in non-adopting states.

We borrow from Hillman et al. (2014) when discussing robustness across multiple comparison groups: (a) one comparison group yields a statistically significant result and equals “limited” evidence, (b) two or three groups equals stronger evidence, and (c) all four comparison groups yield statistically significant results, which is the strongest evidence possible. Alternatively, if our estimates have no significant patterns across all four comparison groups, then we conclude that the policy had null effects on that particular outcome.

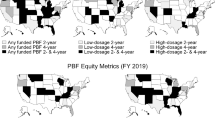

Over the course of our analytical sample, 82 institutions were under a broad-based merit-aid program, 195 institutions were afforded the authority to set their own tuition, and 38 institutions operated both under a broad-based merit-aid policy and decentralized tuition-setting authority.

References

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Baum, S., & Lapovsky, L. (2006). Tuition discounting: not just a private college practice. New York: College Board.

Belasco, A. S., Rosinger, K. O., & Hearn, J. C. (2015). The test-optional movement at America’s selective liberal arts colleges: A boon for equity or something else? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(2), 206–223.

Bell, A. C., Carnahan, J., & L’Orange, H. P. (2011). State tuition, fees, and financial assistance policies: For public colleges and universities, 2010–11. State higher education executive officers.

Bennett, W. J. (1987). Our greedy colleges. The New York times. http://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/18/opinion/our-greedy-colleges.html.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Bettinger, E., Gurantz, O., Kawano, L., & Sacerdote, B. (2016). The long run impacts of merit aid: Evidence from California’s Cal Grant (No. w22347). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bradbury, J. C., & Campbell, N. D. (2003). Local lobbying for state grants: Evidence from Georgia’s HOPE scholarship. Public Finance Review, 31(4), 367–391.

Breneman, D. W., & Finney, J. E. (1997). The changing landscape: Higher education finance in the 1990s. Public and private financing of higher education (pp. 30–59).

Bruce, D. J., & Carruthers, C. K. (2014). Jackpot? The impact of lottery scholarships on enrollment in Tennessee. Journal of Urban Economics, 81, 30–44.

Cellini, S. R., & Goldin, C. (2014). Does federal student aid raise tuition? New evidence on for-profit colleges. American Economic Journal, 6(4), 174–206.

Cohodes, S. R., & Goodman, J. S. (2014). Merit-aid, college quality, and college completion: Massachusetts’ Adams scholarship as an in-kind subsidy. American Economic Journal, 6(4), 251–285.

Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1986). The causal assumptions of quasi-experimental practice. Synthese, 68(1), 141–180.

Cornwell, C., Mustard, D., & Sridhar, D. (2006). The enrollment effects of merit-based financial aid: evidence from Georgia’s HOPE program. Journal of Labor Economics, 24, 761–786.

Creech, J. D. (1998). State-funded merit scholarship programs: why are they popular? Can they in-crease participation in higher education?. Atlanta: Southern Regional Education Board.

Curs, B. R., & Dar, L. (2010). Do institutions respond asymmetrically to changes in state need-and merit-based aid? Available at SSRN 1702504.

Deaton, R. (2006). Policy shifts in tuition setting authority in the American States: An events history analysis of state policy adoption. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Leadership, Policy, and Organizations, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University.

Delaney, J. A., & Doyle, W. R. (2011). State spending on higher education: Testing the balance wheel over time. Journal of Education Finance, 36(4), 343–368.

Delaney, J. A., & Ness, E. C. (2013). Creating a merit aid typology. Merit aid reconsidered, new directions in institutional research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

DesJardins, S. L., Ahlburg, D. A., & McCall, B. P. (2006). The effects of interrupted enrollment on graduation from college: Racial, income, and ability differences. Economics of Education Review, 25(6), 575–590.

Doyle, W. R. (2006). Policy adoption of state merit aid programs: An event history analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 28(3), 259–285.

Doyle, W. R. (2010). Does merit-based aid “crowd out” need-based aid? Research in Higher Education, 51(5), 397–415.

Doyle, W. R. (2012). The politics of public college tuition and state financial aid. The Journal of Higher Education, 83(5), 617–647.

Drukker, D. M. (2003). Testing for serial correlation in linear panel-data models. Stata Journal, 3(2), 168–177.

Dynarski, S. (2000). Hope for whom? Financial aid for the middle class and its impact on college attendance. National Tax Journal, 53, 629–661.

Dynarski, S. (2002). The behavioral and distributional implications of aid for college. American Economic Review, 92(2), 279–285.

Dynarski, S. (2004). The new merit aid. College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 63–100). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ehrenberg, R. G. (2002). Tuition rising: Why college costs so much. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fitzpatrick, M. D., & Jones, D. (2016). Post-baccalaureate migration and merit-based scholarships. Economics of Education Review, 54, 155–172.

Fulton, M. (2015). Community colleges expanded role into awarding bachelor’s degrees. ECS education policy analysis. Education commission of the States.

Geiger, R. L. (2004). Knowledge and money: Research universities and the paradox of the marketplace. California: Stanford University Press.

Griffith, A. L. (2011). Keeping up with the Joneses: Institutional changes following the adoption of a merit aid policy. Economics of Education Review, 30(5), 1022–1033.

Harrington, J. R., Muñoz, J., Curs, B. R., & Ehlert, M. (2016). Examining the impact of a highly targeted state administered merit aid program on brain drain: Evidence from a regression discontinuity analysis of Missouri’s Bright flight program. Research in Higher Education, 57(4), 423–447.

Hauptman, A. (1990). The tuition dilemma: Assessing new ways to pay for college. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Hawley, Z. B., & Rork, J. C. (2013). The case of state funded higher education scholarship plans and interstate brain drain. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 43(2), 242–249.

Hearn, J. C., Griswold, C. P., & Marine, G. M. (1996). Region, resources, and reason: A contextual analysis of state tuition and student aid policies. Research in Higher Education, 37(3), 141–178.

Heller, D. E. (2001). The states and public higher education policy: Affordability, access, and accountability. Baltimore: JHU Press.

Heller, D. E. (2002). The policy shift in state financial aid programs. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 221–261). Netherlands: Springer.

Heller, D. E. (2004). NCES research on college participation: A critical analysis. In E. P. St. John (Ed.), Readings on equal education: Vol. 19, Public policy and college access: Investigating the federal and state roles in equalizing postsecondary opportunity (pp. 29–64). New York: AMS Press, Inc.

Heller, D. E., & Marin, P. (Eds.). (2004). State merit scholarship programs and racial inequality. Cambridge: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller, D., & Rasmussen, C. (2001). Merit scholarships and college access: Evidence from two states. State merit aid programs: College access and equity. Cambridge: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller, D. E., & Rogers, K. R. (2006). Shifting the burden: Public and private financing of higher education in the United States and implications for Europe. Tertiary Education and Management, 12(2), 91–117.

Henry, G. T., Rubenstein, R., & Bugler, D. T. (2004). Is HOPE enough? Impacts of receiving and losing merit-based financial aid. Educational Policy, 18(5), 686–709.

Hillman, N. W., Tandberg, D. A., & Gross, J. P. (2014). Market-based higher education: does Colorado’s voucher model improve higher education access and efficiency? Research in Higher Education, 55(6), 601–625.

Hoxby, C. M. (1997). How the changing market structure of US higher education explains college tuition (No. w6323). New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hu, S., Trengove, M., & Zhang, L. (2012). Toward a greater understanding of the effects of state merit aid programs: Examining existing evidence and exploring future research direction. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 291–334). Netherlands: Springer.

Jaquette, O., & Parra, E. E. (2014). Using IPEDS for panel analyses: Core concepts, data challenges, and empirical applications. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 467–533). Netherlands: Springer.

John, E. P. S. (1992). Changes in pricing behavior during the 1980s: An analysis of selected case studies. The Journal of Higher Education, 63(2), 165–187.

Kim, J., & Stange, K. (2016). Differential pricing in the wake of tuition deregulation at Texas public universities. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(1), 112–146.

Lan, Y., & Winters, J. V. (2011). Did the DC tuition assistance grant program cause out-of-state tuition to increase? Economics Bulletin, 31(3), 2444–2453.

Long, B. (2004). How do financial aid policies affect colleges? The Institutional impact of the Georgia HOPE scholarship. The Journal of Human Resources, 39, 1045–1066.

Lowry, R. C. (2001). Governmental structure, trustee selection, and public university prices and spending: Multiple means to similar ends. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 845–861.

Lyall, K. C., & Sell, K. R. (2006). The de facto privatization of American public higher education. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 38(1), 6–13.

McLendon, M. K., Hearn, J. C., & Hammond, R. G. (2013). Pricing the flagships: The politics of tuition setting at public research universities. Retrieved from: http://www.4.ncsu.edu/~rghammon/Pricing_the_Flagships.pdf.

McLendon, M. K., Tandberg, D. A., & Hillman, N. W. (2014). Financing college opportunity: Factors influencing state spending on student financial aid and campus appropriations, 1990 through 2010. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 655(1), 143–162.

Meyer, B. D. (1995). Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. Journal of business and economic statistics, 13(2), 151–161.

Mumper, M. (2001). State efforts to keep public colleges affordable in the face of fiscal stress. In M. Paulsen & J. Smart (Eds.), The finance of higher education: Theory, research, policy, and practice (pp. 321–395). New York: Agathon Press.

Ness, E. C. (2010). The politics of determining merit aid eligibility criteria: An analysis of the policy process. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(1), 33–60.

Paulsen, M. B. (1991). College tuition: Demand and supply determinants from 1960 to 1986. The Review of Higher Education, 14(3), 339–358.

Ringquist, E. J., & Garand, J. C. (1999). Policy change in the American States. In R. E. Weber & P. Brace (Eds.), American state and local politics (pp. 268–299). New York: Catham House Publishing.

Rizzo, M. J., & Ehrenberg, R. (2004). Resident and non-resident tuition and enrollment at state flagship universities. In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), College Choices: The Economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 303–354). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rogers, K. & Heller, D.E. (2003) Moving on: State policies to address academic brain drain in the south. Paper presented at the Association for the Study of Higher Education Annual Meeting November 12–16, Portland.

Rothschild, M., & White, L. J. (1995). The analytics of the pricing of higher education and other services in which the customers are inputs. Journal of Political Economy, 103(3), 573–586.

Rusk, J. J., & Leslie, L. L. (1978). The setting of tuition in public higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 49(6), 531–547.

Scott-Clayton, J. (2011). On money and motivation a quasi-experimental analysis of financial incentives for college achievement. Journal of Human Resources, 46(3), 614–646.

Shadish, W. R., Clark, M. H., & Steiner, P. M. (2008). Can nonrandomized experiments yield accurate answers? A randomized experiment comparing random and nonrandom assignments. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(484), 1334–1344.

Singell, L. D., Jr., Waddell, G. R., & Curs, B. R. (2006). HOPE for the Pell? Institutional effects in the intersection of merit-based and need-based aid. Southern Economic Journal, 73, 79–99.

Singell, L. D., & Stone, J. A. (2007). For whom the Pell tolls: The response of university tuition to federal grants-in-aid. Economics of Education Review, 26(3), 285–295.

Sjoquist, D. L., & Winters, J. V. (2014). Merit aid and post-college retention in the state. Journal of Urban Economics, 80, 39–50.

Sjoquist, D. L., & Winters, J. V. (2015). State merit aid programs and college major: A focus on STEM. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(4), 973–1006.

Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2008). Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors for fixed effects panel data regression. Econometrica, 76(1), 155–174.

Tandberg, D. A. (2013). The conditioning role of state higher education governance structures. The Journal of Higher Education, 84(4), 506–543.

Titus, M. A., Vamosiu, A., & Gupta, A. (2015). Conditional convergence of nonresident tuition rates at public research universities: a panel data analysis. Higher Education, 70(6), 923–940.

Turner, L. J. (2012). The incidence of student financial aid: Evidence from the Pell grant program. Unpublished manuscript. http://www.columbia.edu/~ljt2110/LTurner_JMP.pdf.

Warne, T. R. (2008). Comparing theories of the policy process and state tuition policy: Critical theory, institutional rational choice, and advocacy coalitions (Doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri–Columbia).

Wellman, J. (1999). The tuition puzzle: Putting the pieces together: The new millennium project on higher education costs, pricing, and productivity.

Wooldridge, M. (2009). An introduction to multiagent systems. Hoboken: Wiley.

Zhang, L. (2011). Does merit-based aid affect degree production in STEM Fields? Evidence from Georgia and Florida. The Journal of Higher Education, 82(4), 389–415.

Zhang, L., Hu, S., & Sensenig, V. (2013). The effect of Florida’s Bright Futures program on college enrollment and degree production: An aggregated-level analysis. Research in Higher Education, 54(7), 746–764.

Zhang, L., & Ness, E. (2010). Does state merit-based aid stem brain drain. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 143–165.

Zinth, K., & Smith, M. (2012). Tuition-setting authority for public colleges and universities. Education Commission of the States. Retrieved from http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/01/04/71/10471.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kramer, D.A., Ortagus, J.C. & Lacy, T.A. Tuition-Setting Authority and Broad-Based Merit Aid: The Effect of Policy Intersection on Pricing Strategies. Res High Educ 59, 489–518 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9475-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9475-x