Abstract

By creating a comprehensive corporate social- and environmental-related lexicon, this paper examines the extent to which board diversity impacts social and environmental disclosures. Contributing to diversity literature, we rely on the faultlines concept, postulated and developed by organizational research, which is hypothetical dividing lines that split a boardroom into relatively homogeneous subgroups based on directors’ diversified attributes. Employing a sample of FTSE All-share non-financial firms, our findings show that firms with higher faultline strength in the boardroom (i.e., relatively more homogeneous subgroups) exhibit significantly lower levels of both social and environmental disclosures in their narrative sections of annual reports. This implies that board diversity faultlines are likely to have a detrimental effect on corporate boards regarding reaching a consensus decision on disclosing information on social and environmental aspects. Our results remain robust after a battery of sensitivity tests and addressing potential endogeneity problems. Our results provide timely evidence-based insights into major recent structural reforms aiming at proposing remedies to corporate governance problems in the UK, specifically that interest should not be confined to board diversity per se but configurations (the extent of convergence) between the diversified attributes. Furthermore, the evidence provided by our paper should be of interest to the UK’s regulatory bodies (Financial Reporting Council) considering their increasing focus and pursuit to understand the underlying challenges of corporate social and environmental reporting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Remarkably, while there has been an increasing interest in studying the antecedents and factors related to corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities (e.g., De Villiers and Marques 2016; Jackson et al. 2019; Michelon and Parbonetti 2012; Muslu et al. 2019; Li et al. 2022; Al-Shaer et al. 2023; Trinh et al. 2023), little attention has been paid toward the impact of board diversity measures on social and environmental disclosures (SED) (Gibson and O'Donovan 2007; Qiu et al. 2016; Terjesen et al. 2009). In addition, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no prior studies analysing the relationship between board of director diversity faultlines, that split a boardroom into moderately homogeneous subgroups dependent on individual directors’ characteristics, and SED practices. Indeed, both board diversity and the firm’s environmental and social reporting are of interest to business communities, different stakeholders, and policymakers (e.g., FRC, 2018; Hoang et al. 2018b, a; Li et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2023).

Diversity is the differences among team members’ attributes (e.g., age, gender, and nationality) that may lead to the perception of being different (e.g., van Knippenberg et al. 2011). Thus, diversity can be looked at as the mix of different attributes within a group of directors and that mix can attribute positively or negatively to the organization. Over the past few decades, there has been ongoing debate as to the extent to which the diversity of team members might have an impact on their processes and outcomes. The empirical evidence (principally concerning firm performance or risk) does not show inclusive and consistent answers for such a question (for meta-analysis papers, we can refer to, e.g., Guillaume et al. 2012), as the findings seem to be subject to context and depend on many different factors. One of the suggestions to overcome this issue is to look at how attributes are allocated across the board and how such allocations are associated with the board’s outcomes (e.g., Meyer and Glenz 2013). Therefore, organizational research postulates the diversity faultlines concept, defined as hypothetical dividing lines that split a team into relatively homogeneous subgroups according to their alignment along diversified attributes, thereby suggesting an impact on team-level outcomes (Lau and Murnighan 2005; Thatcher and Patel 2012). Faultlines, therefore, is opposite to diversity as it captures the configurations between different attributes. Practically, it looks at the different ways in which different director attributes (diversity) can be aligned together and can lead to dividing that group into some other distinctive subgroups.Footnote 1

Accordingly, and in response to Meyer and Glenz (2013), we advance literature on diversity by exploring the association between board of director faultline strength and SED. Therefore, rather than examining the heterogeneity of a single individual attribute within the boardroom, as typically done by previous studies, we capture and investigate the configurations between board of directors diversified attributes simultaneously. It is important to note that faultline is not an overall/compound measure for diversity, but it is a measure of the extent to which different attributes for a diverse board converge in a way in which board members can be split into homogeneous (hypothetical) subgroups based on these attributes. For this reason, faultlines require diversity as a precondition because in a homogenous team or extremely different team faultlines are less likely to be formed. This, accordingly, features our work since the link between faultline strength and team outcomes goes beyond individual diversity measures studied in prior research (Lau and Murnighan 2005). For a review of the faultline constructs, we refer to Meyer and Glenz (2013).

While some stakeholders concentrate on financial returns, others are concerned about the adverse social and environmental effects of a company’s operation. Thus, the board of directors’ social and environmental decision making represents a compromise between competing stakeholder demands. Therefore, a boardroom requires diversification to better tackle problems faced by different stakeholders (e.g., Zhang and Li 2024; Hoang et al. 2018b, a; Ellis and Keys 2015; Singh et al. 2001); ultimately, to represent distinct interest groups, including financial and non-financial objectives of various stakeholders (Cao et al. 2019; Aguilera et al. 2019; Desender et al. 2020; Mallin et al. 2013). Research on the implications of boardroom diversity on corporate social and environmental reporting need further investigation (Byron and Post 2016; Hsu et al. 2017; McGuinness et al. 2017; Post et al. 2011). In this regard, board diversity literature (Katmon and Farooque 2017; Lau et al. 2016) documents the need to rely on multi-dimensional diversity measures to study the impact of board diversity on SED. Thus, this paper fills this gap by examining faultline strength, as a measure for diversity that combines several directors’ characteristics comprising director age, gender, and nationality, on SED.

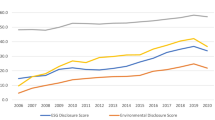

In doing so, and different from extant literature (Ben-Amar et al. 2017; Jain and Jamali 2016; Katmon and Farooque 2017), our paper captures faultline strength on the basis of alignments between directors based on their demographic characteristics that include age, gender, and nationality attributes (e.g., Jaeger et al. 2016; Schmid et al. 2015). Consequently, we utilize the most versatile and accurate measure for faultline strength proposed by Meyer and Glenz (2013), which is available at http://www.group-faultlines.org.Footnote 2 Our paper measures SED, using automated textual content analysis, as the percentage of the number of words that are indicative of social and environmental information for FTSE All-Share index non-financial companies from 2005 to 2018. To that end, our paper develops a comprehensive wordlist that captures the social and environmental information in annual report narratives.

Our results show that firms with higher faultline strength in the boardroom exhibit significantly lower levels of both social and environmental disclosures in their annual report narratives. From an economic perspective, the results show that board of directors faultline strength is associated with 7.94% lower SED, 7.92% lower environmental disclosures (ED), and 4.02% lower social disclosures (SD). This implies that board diversity faultlines are likely to have a detrimental effect on corporate boards, resulting in a decrease of disclosing information on social and environmental aspects. This evidence explains the results obtained by many recent studies on gender diversity (Ben-Amar et al. 2017; Cabeza‐García et al. 2018; Hoang et al. 2018b, a; Post et al. 2015). These results improve the current understanding of board diversity and CG’s involvement, and are beneficial to government and policymakers concerned with the effect of the governance system on targets for SED. This study’s findings add weight to stakeholder demand for a comprehensive structure to establish acceptable standards for reporting and verification of SED. Our inferences remain robust after various sensitivity tests and addressing potential endogeneity problems that are attributable to self-selection bias, simultaneity, and/or omitted variables.

Our paper contributes to the current literature in the following ways. First, our paper is the first to investigate the relationship between faultline strength and textual SED in the UK context over a long period of time, making this paper, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first that measures faultline strength based on a combination of different directors’ characteristics, using real corporate data. Previous diversity research (e.g., Ben-Amar et al. 2017; Cabeza‐García et al. 2018; Jizi 2017; Nadeem 2020) has attempted to identify a single proxy for capturing board diversity (i.e., traditional diversity); however, such attempts have not typically captured the joint effects of multiple diversity attributes. Inferences stemmed from prior research are, therefore, limited to a single measure of diversity and do not represent the joint effect of different diversity attributes that really exist in boardrooms. To overcome such prior limitations, we measure faultline strength that captures the joint demographic attributes in boardrooms (i.e., gender diversity, and nationality). Furthermore, prior faultline research (Meyer and Glenz 2013; Thatcher and Patel 2012) captures diversity based on experimental or hypothetical limited data. Second, the relationship between diversity and SED is debated as the extant evidence is mixed. Our empirical findings provide novel evidence that is consistent with theoretical expectation that a strong faultline is adversely associated with SED (Thatcher and Patel 2012). Third, our paper provides a comprehensive lexicon of SED-related words. This lexicon aims to capture the social and environmental information in annual report narratives and assist future SED research in studying and measuring textual scores for these two increasingly important elements of SED.

Our findings have theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, ignoring the multi-dimensionality aspect of diversity might be a contributing factor to the extant inconsistent empirical evidence linking diversity to firms’ social or environmental activity disclosures, confirming the complex nature of the underlying concept of diversity to be quantified by looking, alone, into individual attributes. Practically, regulatory bodies should, therefore, integrate associated regulations on diversity to ensure effectiveness of application for diversity policies. Additionally, our results support the trend of regulation in the UK in SED that stresses the role of directors in facilitating the process of disclosing social and environmental information. Nevertheless, these results show that more reforms are needed in the UK context and it would be desirable to realise improved board diversity across multiple levels especially keeping in mind the director and board-level dimensions. Consequently, a board with diverse members represents a wide spectrum of interests and serves as a medium to address real and inseparable conflicts between financial (Gamerschlag et al. 2011; Shaukat et al. 2016), social (De Villiers and Marques 2016; Gregory et al. 2014; Haniffa and Cooke 2005; Mallin et al. 2014) and environmental demands (Ben-Amar et al. 2017; Liao et al. 2015; Tauringana and Chithambo 2015). Specifically, our paper is timely to provide evidence-based insights into the four recent reviews of the UK’s corporate governance (CG) environment (BEIS, 2019; Brydon 2019; CMA, 2019) aiming at proposing remedies to CG and reporting problems in the UK, that interest should not be confined to board diversity per se but configurations (the extent of convergence) between the diversified attributes. Furthermore, the evidence provided by our paper should be of interest to the UK’s regulatory bodies (Financial Reporting Council) considering their increasing focus and pursuit to understand the underlying challenges of corporate social and environmental reporting.

This paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 reviews relevant literature and develops the research hypothesis; Sect. 3 introduces research methods; Sect. 4 discusses empirical results, and Sect. 5 conduces and provides several avenues for future research.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

This paper advances literature on SED and boardroom diversity by examining faultline strength that combines board of directors’ multiple diversity attributes, namely, age, gender, and nationality, since they are ideal and provide desirable faultline measurement properties (e.g., Lau and Murnighan 1998, 2005; Meyer and Glenz 2013; Thatcher and Patel 2011, 2012). In boardrooms, gender diversity is an essential aspect of CG, since men and women are biologically, culturally and sociologically different (Byron and Post 2016). For example, the current literature (Liao et al. 2015; Nekhili et al. 2017) shows that women vary in attitude from men, in networking skills, level of education, and work experience/knowledge. Nadeem (2020) argues that women are more dedicated, active, attentive and contribute to a healthy environment on a board. Likewise, female directors are found to be less ego-interest-oriented, thereby boosting the decision-making process and board productivity (Galbreath 2016). Therefore, women’s engagement within the board has a positive effect on the socially responsible actions of an organization (Rao and Tilt 2016). As a result, female directors are more likely to be appointed and to take on board roles related to environmental and sustainable development challenges (Bear et al. 2010; Byron and Post 2016; Cabeza‐García et al. 2018; Liao et al. 2015; Nekhili et al. 2017; Post et al. 2015; Rao and Tilt 2016; Shaukat et al. 2016), as these types of roles are more closely allied to their societal roles. Liao et al. (2015) show that female directors increase the propensity to disclose SED, and this is consistent with stakeholder theory. In this regard, stakeholder theory adopts a specific definition of a board’s overall dual-responsibilities to various stakeholders with conflicting ideologies, which is likely to provide a more explicit reason for the disclosure practices examined in this paper.

Despite theoretical support for the importance of gender diversity, empirical evidence is mixed. Some studies indicate that female directors play an insignificant role in environmental aspects based on sexual stereotypes (Galbreath 2011) indicating that women are anxious but only in relation to a limited set of risk-related environmental issues, resulting in an insignificant impact on their environmental concerns. Ben-Amar et al. (2017) highlight that although men and women are different in terms of their knowledge of scientific matters, it seems to have little impact on their environmental attitudes. Recent diversity literature (Byron and Post 2016; Cabeza‐García et al. 2018; Liao et al. 2015; Nekhili et al. 2017; Post et al. 2015; Rao and Tilt 2016; Shaukat et al. 2016) shows evidence that female directors make a substantial contribution to a board, and gender diversity is highlighted in several recent policy reform initiatives (e.g., FRC 2018). Therefore, the presence of women on a board is predicted to increase the propensity for SED.

Director nationality has been used by prior research to capture diversity (Hoang et al. 2018a, b; Post et al. 2011). Nationality is captured by culture, which reflects directors’ behavioural patterns (e.g., Hoang et al. 2018a, b) and/or ethnicity, with the latter reflecting the origins of directors (Post et al. 2011). Another line of research confirms the significant positive effect of director nationality on social disclosure (Fakoya and Lawal 2020; Katmon et al. 2019; Khan et al. 2013). Additionally, several recent studies find that nationality-based diversity helps in protecting the rights of society and, in turn, increases SED (e.g., Gantyowati and Agustine 2017; Rao and Tilt 2016). Resource dependence theory explains how directors diversity (e.g., on the basis of nationality diversity) brings various resources to the organization (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) and provides vital resources to the boardroom (Parker 2016) including by combining diverse knowledge into a corporate disclosure strategy. Similar to resources brought by the diversity in gender and nationality, prior research suggests the importance of age diversity on board outcomes, albeit results are somewhat limited and inconclusive when considered in isolation (e.g., Backes-Gellner and Veen 2013; Bell et al. 2011; Bunderson and Sutcliffe 2002; Horwitz and Horwitz 2007; Joshi and Roh 2009; Schneid et al. 2016).

Faultline theory focuses on a combination of diversified board of directors attributes rather than looking at individual characteristics as a stand-alone factor. The possibility of forming subgroups is likely to happen due to the possibility of alignments between directors’ individual characteristics. Thus, faultline strength measures the extent to which a subgroup shares the same/similar characteristics, suggesting that a strong faultline significantly increases conflict between groups (e.g., Meyer and Glenz 2013; Thatcher and Patel 2011, 2012; Xue et al. 2024). Therefore, faultline is typically associated with negative outcomes, as they suggest the potential for significant subgroup conflict. The theoretical framework on board faultlines suggests that alignment of directors’ attributes, such as age, gender, or nationality, may form discernible subgroups, leading to faultlines.

In the context of disclosures, such faultlines may lead to disagreements on what should be disclosed, how, and when, as well as on the interpretation of disclosure regulations or the strategic value of transparency. Subgroups may have different risk tolerances, strategic priorities, or stakeholders’ interests at heart, which can result in inconsistent or incomplete disclosures. This conflict can manifest in delays, lack of consensus, or even the withholding of information, potentially compromising the quality and timeliness of disclosures and thus negatively impacting the firm’s transparency and perceived integrity. Boards with strong faultlines may struggle to present a united front, leading to reduced investor confidence and ultimately affecting the firm’s performance and market standing (e.g., Van Peteghem et al. 2018; Elshandidy et al. 2024). Previous research suggests that faultiline diversity hinders smooth decision-making by boards and impedes formation of corporate strategies such as disclosure policies (Cole and Salimath 2013; Das Neves and Melé 2013; Thatcher and Patel 2012; Arena et al. 2024), as well as slowing down the exchange of information among board members (Jaeger et al. 2016), similar to lowering firm performance and less effective CEO oversight (e.g., Van Peteghem et al. 2018).

Based on the discussion above, our paper posits that pronounced faultlines within boards are likely to have an adverse association with SED. Given the strategic nature of SED, which requires a unified and coherent approach from the board of directors, the presence of strong faultlines can be particularly disruptive. Effective SED relies on the board’s collaborative effort in overseeing and executing critical functions such as monitoring, strategy implementation, executive compensation, and capital acquisition capital (e.g., Van Peteghem et al. 2018). These functions are predicated on robust internal communication, mutual trust, and respect for diverse opinions among board members—elements that are undermined in boards fragmented by pronounced faultlines. When board members are divided into homogeneous subgroups, the consequential disagreement is likely to negatively affect the collective decision-making process, essential for conveying the company’s social and environmental stance comprehensively and transparently. Such divisions may lead to conflict in what is communicated, resulting in SED that fails to accurately reflect the firm’s policies or to meet stakeholder expectations for transparency and accountability. This leads to formulating this paper’s hypothesis as follows:

H1

There is a negative association between the board of directors faultline strength and SED in narrative sections of annual reports, ceteris paribus.

3 Research design

3.1 Sample

We obtain an initial sample for FTSE All-Share firms from the Refinitiv Eikon database covering the period 2005–2018. Following prior research, we end our sample in 2018 to avoid the effect of other potential confounding events and thereby the possibility of results bias due to measurement error endogeneity bias (e.g., DeFond et al. 2015; Porumb et al. 2021; Elsayed and Elshandidy 2021; Lennox et al. 2023). This is important due to major disruptions to workplace diversity and inclusion and corporate disclosures that came during the Brexit chaos, which lasted between 2019 and 2020 and were followed by the coronavirus crisis between 2020 and 2021 (e.g., Parliament 2021; FRC 2020; Forbes 2019; Torreggiani and De Giacomo 2022; Elsayed et al. 2023). This also helps because the labor work exerted to manually collect UK annual reports to retrieve qualitative data is substantially time and effort-consuming.

Recall, faultlines are hypothetical dividing lines based on director attributes that split a board of directors into relatively homogeneous subgroups (Thatcher and Patel 2011). Since our faultline variable is measured in the presence of three subgroups (i.e., age, gender, and nationality attributes) (e.g., Jaeger et al. 2016; Schmid et al. 2015), we utilize the most versatile and accurate measure for faultline strength proposed by Meyer and Glenz (2013). Specifically, we employ the free open-source statistical environment R (R Development Core Team, 2012) provided by Meyer and Glenz (2013), available at http://www.group-faultlines.org, to calculate our faultline measure using age, gender, and nationality attributes of directors on the board of directors.Footnote 3

For a given firm to be included in our sample, we require BoardEx database to include director information required to measure the faultline variable, namely age, gender, and nationality. We exclude all firms in the financial (SIC between 6000 and 6999) and utility (SIC between 4000 and 4999) industries, due to their distinct regulations, accounting practices and financial reporting systems. We exclude firms missing adequate data to measure SED variables, firms with annual reports missing or unreadable by Diction 7 software (e.g., secured PDFs or PDFs unconvertable to text files). We exclude firms missing the necessary data to measure the BoardEx CG and Refinitiv Eikon DataStream financial and market control variables. We also collect data on analyst coverage from the Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System (IBES) data set on DataStream. This yields a final sample of 2,044 firm-year observations. Appendix 2 gives the variable definitions and their sources.

3.2 Textual SED analysis

This paper creates a comprehensive list of SED-related keywords to capture the SED in annual report narratives. In line with most prior textual analysis studies in accounting and finance (e.g., Elsayed and Elshandidy 2020), we adopt the bag of words method (Loughran and McDonald 2011), in which the annual reports are parsed into a matrix composed of words and word count vectors. Our approach is consistent with the Loughran and McDonald (2016) assertion of the importance of developing a wordlist in the context of each textual-subject study, as reliance on a wordlist that is derived from a different subject would probably cause spurious results (Loughran and McDonald 2016).

The following procedures are applied to establish the wordlist. (1) We review SED academic studies keywords (Albertini 2014; Gamerschlag 2013; Gamerschlag et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013; Wu 2013), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) framework, e.g., GRI standards 305/2016 (2016: https://www.globalreporting.org/), FRC work on environmental, social governance and climate related reporting 2018 (https://www.frc.org.uk/), ICAEW library of environmental, social and sustainability reporting (2020: https://www.icaew.com/), and Environmental Reporting Guidelines (2019: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/). This step enables identification of the initial wordlist. (2) Following prior research (e.g., Elsayed and Elshandidy 2020), the initial wordlist is expanded by including related synonyms using Roget’s Thesaurus (http://www.roget.org/). (3) To develop the wordlist further, following prior research (e.g., Clatworthy and Jones 2003; Kravet and Muslu 2013), 30 annual reports are randomly selected and carefully read to recognize words that are indicative of the SED. (4) To test the extent to which the words featured in the resulting list are in use, an intensive text search, using QSR version 6 software, is conducted for another 15 randomly selected annual reports. Any words that do not appear in this text search are excluded (e.g., Elshandidy and Shrives 2016). Then, consistent with the prior literature (e.g., Milne and Gray 2013; Gamerschlag et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013; Wu 2013) and our research design purposes, the SED aggregate wordlist is assessed and classified into two categories, namely, environmental- and social-related concepts, used to capture environmental disclosure and social disclosure separately. The final SED wordlist is presented in Appendix 3.

To measure the SED score, as is typically done in textual analysis literature (see the review of Loughran and McDonald 2016), we calculate the percentage of words indicating SED in the narrative sections of annual reports (i.e., the number of SED-related words scaled by the total number of words in the annual report). We assure the reliability and validity of the SED and its categories of environmental and social measures by using Cronbach’s alpha statistical analysis (Elshandidy and Shrives 2016). The Cronbach’s alpha of 94.41% for the computed scores of the SED, as well as its categories of environmental disclosure and social disclosure, implies that the internal consistency between the SED and its categories is high relative to the generally accepted value in social science of 70% (e.g., Elsayed and Elshandidy 2021). Furthermore, we adopt manual coding for 30 randomly selected firms, and we find no significant differences between the three independent coders (Karim et al. 2021). It is, therefore, concluded that the computed SED measures are reliable and valid.

3.3 Empirical model

We employ the following ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions model to test our hypothesis on the relationship between the faultline strength and SED:

where in separate tests, SED equals the score of aggregate social and environmental disclosure (SED), the score of the social disclosure (SD), or score of environmental disclosure (ED). Faultline, our independent variable of interest, ranging from zero to one, captures the faultline strength on the board of directors. Following prior literature (e.g., Katmon et al. 2019; Khan et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2021; Michelon et al. 2015; Nadeem 2020; Trang Cam et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2017), we control for the following firm-level and other board of directors variables: firm size (Firm_Size), return on assets (ROA), capital structure (Leverage), market to book ratio (MTB), firm age (Firm_Age), frequency of board of directors meetings (Board_Meetings), board of directors size (Board_Size), board of directors independence (Board_Independence), audit committee size (AC_Size), audit committee independence (AC_Independence), financial experts on audit committee (AC_Expertise), CEO duality (Duality), and a dummy variable to capture firms belonging to social or environmental sensitive industries (ESSI). We further use industry and year fixed effects to control for inherently volatile industries and unobserved effects over the years, as well as robust standard errors that control for both serial correlation and heteroscedasticity. Additionally, we winsorize continuous variables on the 1% of both tails to mitigate the influence of outliers.Footnote 4 Appendix 2 gives the variable definitions and their sources.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics reported in Table 1 display the distributional properties of the variables used in our main analyses on whether there is association between the board of directors faultline strength and SED. On average, the percentage of words that reflect social and environmental information represents about 10.38% relative to the total number of words disclosed by UK non-financial firms in their annual report narratives. On average, about 8.23% of the annual report narratives disclose environment-related information, while 5.75% of the annual report narratives disclose social-related information. These variables’ inter-quartiles, ranging from 9.82%, 7.77%, and 5.75% to 11.02%, 8.76%, and 6.18%, respectively, imply a significant cross-sectional variation in the environmental and social content of the annual report narratives. This also suggests that consistent with heightened concern for environmental and social issues in the UK (e.g., ICAEW library of Environmental, social and sustainability reporting: https://www.icaew.com/), the non-financial firms devoted considerable content to disclose their environmental and social activities in their annual report narratives. Additionally, on average, the mean value of faultline is about 0.59, where the variable’s inter-quartiles range from 0.46 to 0.67. This implies a significant cross-sectional variation in the faultline variable. This, on average, also suggests that there is a moderate faultline strength in the boards of directors of the UK non-financial firms.

Table 2 reports the pair-wise correlations (Pearson product moment correlations are exhibited on the upper-right-hand portion, and Spearman rank-order correlations are exhibited on the lower-left-hand portion). We discuss the Spearman rank-order correlations but note that the Pearson correlations are generally consistent with the Spearman rank-order correlations. At the 5% significance level, as expected, the SED variable is positively associated with its categories of ED (0.933) and SD (0.891) which, again, implies that the UK non-financial firms significantly employ the annual report narratives to communicate signals about their environmental and social activities. Consistent with our expectations, the faultline variable is negatively correlated with SED (− 139), ED (− 0.142), and SD (− 0.120). These bivariate results come consistent with prior research and give initial support to our research hypothesis.

4.2 Faultline strength and SED

Models 1 through 3 of Table 3 report results related to our research hypothesis on the association between the faultline strength and SED. Across each of the three models’ estimations, faultline is negatively associated with the level of SED, and its categories of ED and SD. Collectively, this finding suggests that firms with stronger faultline strength show significantly lower levels of SED, which are observed in terms of aggregate SED (t-statistic − 0.427, significant at the 1% level) and its categories of ED (t-statistic − 0.426, significant at the 1% level), and SD (t-statistic − 0.216, significant at the 5% level). To put this in an economic perspective, all else being equal, a one-standard-deviation increase in the board of directors faultline strength is associated with a 7.94% (− 0.427 × 0.186) lower SED, a 7.92% (− 0.426 × 0.186) lower ED, and a 4.02% (− 0.216 × 0.186) lower SD, respectively. This evidence supports H1 that board of directors faultline strength is negatively associated with SED.

Our results are consistent with Lau and Murnighan’s (1998) seminal conceptual work that a team or group (e.g., board of directors) diversity faultline is better understood by considering the impact of different dimensions of diversity in conjunction where the alignment of multiple individual attributes (particularly, gender, age, and nationality) leads to hypothetical dividing lines that are likely to negatively influence the group processes and performance (e.g., Thatcher and Patel 2012; Van Knippenberg et al. 2011). Our results extend and complement the conclusions drawn by prior organizational research on diversity faultlines (e.g., Thatcher and Patel 2012) by suggesting that a board of directors faultline negatively affects the SED. Our findings also accord with prior organizational research suggestions that the faultline concept is applicable to contexts such as boards of directors, with expected negative outcomes on the board level (e.g., Meyer and Glenz 2013).

4.3 Robustness tests

4.3.1 Change analysis faultline strength and SED

We validate our findings and test the robustness in various ways. Prior research (e.g., Elsayed and Elshandidy 2021; Elshandidy and Shrives 2016; Kravet and Muslu 2013) proposes a change analysis technique in order to mitigate endogeneity concerns related to correlated omitted covariates and reverse causality, as well as to establish a strong cause-effect relationship between explanatory and dependent variables. Accordingly, we rerun Eq. (1) while replacing Faultline, SED, and its categories of ED and SD by ∆Faultline, ∆SED, ∆ED, and ∆SD, where ∆ denotes the differences between a firm’s observed value and the median value for other firms in the same industry over the years of study. Models 1 through 3 of Table 4 display results obtained from the change analyses which, collectively, are consistent with those previously obtained from our main analysis. Specifically, the coefficient on the ∆Faultline in the ∆SED, ∆ED, and ∆SD tests is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level (t-statistics are − 3.587, − 4.098, − 2.799, respectively). This, therefore, supports our main findings.

4.3.2 Instrumental variables two-stage least squares (2SLS) model

Consistent with prior research (Adams et al. 2010; Farrell and Hersch 2005), we employ an instrumental variables two-stage least squares (2SLS) statistical technique to address endogeneity concerns. Following previous studies (e.g., Correia 2014; Xing et al. 2021), we employ two instrumental variables: the standard deviation of the number of qualifications of all the firm’s directors over the same period, and the average of time on board values of all the firm’s directors over the same period. Fama (1980) argues that an efficient labor market provides implicit incentives for directors. Thus, a large body of research documents the importance of directors’ qualifications and time on board for governance and that the variation in these two attributes are factored into the way the boards are functioning, diversity is practiced, and board efficacy (Adams et al. 2018; Huang and Hilary 2018; Fedaseyeu et al. 2018; Francis et al. 2015; McIntyre et al. 2007). Forbes and Milliken (1999) argue that job-related diversity like the presence of qualifications on boards would improve the functional area knowledge and skill on board.

In addition, time on boards, on average, also associates with board diversity as it impacts board activities, stultified groupthink, board entrenchment and friendliness, and thereby both the advising and monitoring functions (Kim et al. 2014; Jia 2017; Huang and Hilary 2018; Rosenblum and Nili 2019). Thus, these board attributes are expected to impact the experiential diversity on board and, implying that our instruments are likely to satisfy the relevance condition. In addition, Column 1 of Table 5 shows that our two instruments are jointly significant, no theoretical reason to suspect that these instruments are correlated with the error term, and Columns 1–4 report Partial F statistic, Hansen J statistic (overidentification test—p-value), and Wald test of exogeneity p-value. Collectively, these statistic estimates suggest that instrumental variables used in our analysis are valid and not weak (e.g., Stock et al. 2002; Larcker and Rusticus 2010; Correia 2014). Models 1 through 3 of Table 5 report the 2SLS second stage regressions results, which are all qualitatively consistent with our main findings. This implies that inferences driven by our analyses are not subject to omitted variables bias.Footnote 5

4.3.3 Self-selection bias (Heckman selection model)

Companies in the UK adopt a CG code that is not mandatory but, rather, provides provisions for good governance. That is, the CG code in the UK leaves the company the flexibility to comply or explain why it does not comply. Since complying with the CG code is voluntary, it is possible that our sample is systematically biased because of the role played by the CG (FRC 2018). Therefore, we employ the Heckman (1979) two-step estimation method to correct for self-selection bias resulting from the fact that compliance with the CG code in the UK is a managerial decision rather than a random choice. In the first-stage model, we run probit regression of the likelihood of the choice to have good governance, that complies with the UK’s CG code recommendations, on the firm-level and other board of director characteristics (i.e., those composing the control variables in our main analysis). The first-stage model also includes our two exogenous instruments mentioned in the previous section as suggested by prior research (Feng et al. 2009; Larcker and Rusticus 2010).

Consistent with prior research (Bushman et al. 2004; Defond et al. 2005; Elsayed et al. 2022), we utilize the frequency of board meetings, board of director size, board of director independence, audit committee size, audit committee independence, audit committee financial expertise, and duality role to construct an indicator of good governance, CG_good. Specifically, CG_good is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if the firm’s CG summary is greater than the sample median and zero otherwise. In this respect, we construct a CG summary measure that is equal to the sum of the above-mentioned seven CG variables (i.e., a scale ranging from 0 for lowest to 6 for highest). Each CG continuous variable is turned into a dichotomous variable that takes the value of one if it is greater than the sample median and zero otherwise. In the second step, IMR estimated from the probit model in the first step is included as an additional variable in our analyses of faultline-SED relation. Results reported by Models 1 through 3 of Table 6, using Heckman’s two-step self-selection correction model, are qualitatively similar to those reported under the main analysis, suggesting that our findings are not subject to self-selection bias.

4.3.4 Faultline strength and SED (propensity score matching)

As a further effort to address endogeneity concerns, we employ propensity score matching by establishing a treatment group (e.g., firms with CG_good) matched to a control group (e.g., firms without CG_good). First, we calculate each observation’s propensity score using a logit model that predicts the likelihood of the existence of CG_good as a function of firm-level innate characteristics. Then, we employ propensity score matching without replacement, which means that each firm in the control group can only appear and match one firm in the treated group (Ge and Lennox 2011). We retain only those pairs whose scores match within 0.01 (Donelson et al. 2017). Table 7 shows that our results from the propensity score matching technique are consistent and support our previous results. This also confirms that our results are not subject to endogeneity problems.

4.3.5 Faultline strength and SED (firm fixed effects model)

We further employ a firm fixed effects regression model to account for any possible bias that would arise in the dependent variable due to unobserved heterogeneity of firm-specific and/or industry-specific effects; it also excludes the effects of time-invariant covariates (Elsayed and Elshandidy 2021).Footnote 6 This also addresses any possible endogeneity concerns due to omitted variables (Mekhaimer et al. 2022). Table 8 reports results that are qualitatively consistent with our previous findings and further confirms that the relationship between faultline strength and ESD is not driven by firm-specific unobservable factors.

4.3.6 Faultline strength and SED (additional controls)

Following prior research (e.g., Bassyouny et al. 2022; Elsayed and Elshandidy 2020; Elsayed et al. 2022; Mekhaimer et al. 2022), we present an expanded model with additional control variables to alleviate any possible endogeneity concern that might be attributable to unobservable correlated variables. Specifically, we add the following further control variables: the current ratio as total current assets divided by total current liabilities to account for liquidity; ratio of net funds from operations to total liabilities to account for performance; a compound measure of diversity using principal component analysis (PCA) of age, gender, and nationality attributes of directors on the board of directors to account for directors diversity; market beta, captures firm’s systematic risk, which is calculated as the covariance of a firm’s market return relative to a market index (FTSE All-Share), based on between 23 and 35 consecutive month-end prices; stock volatility, the mean of the volatility (standard deviation) using stock price over the previous 52 weeks; stock return over the firm’s fiscal year; and the analyst coverage as the natural logarithm of the number of analysis, plus one, following the firm as reported by I/B/E/S on DataStream. Table 9 reports our expanded model results which are similar to the main findings.

4.3.7 The moderating role of analyst coverage

We expect the faultline strength in the board of directors to have a lower negative impact on SED for firms with a greater information environment. Information environment can act as a monitoring and discipline mechanism (e.g., Gupta et al. 2018; Lennox et al. 2023). Thus, following prior research (e.g., Botosan 1997; Miller 2010; Blankespoor et al. 2014), we employ analyst coverage as a proxy for the firm’s information environment with a conjecture to find moderating effect to the negative relationship between faultline strength and SED. Specifically, consistent with prior research, we expect faultline strength to have lower negative impact on SED of firms under higher analyst coverage. To test this expectation, we estimate Faultline*Analyst_Coverage as the interaction between Faultline and Analyst_Coverage variables, where following prior research, Analyst_Coverage is a dummy variable takes one if firm analyst coverage is above the sample median and zero otherwise. Supporting our expectation, the coefficient estimates (Faultline + Faultline*Analyst_Coverage) reported by Models 1 through 3 of Table 10 suggest that analyst coverage reduces the negative impact of faultline strength on SEC (− 0.199 = − 0.805 + 0.606), ED (− 0.672 + 0.393), and SD (− 0.430 + 0.348).

Collectively, Tables 4 through 9 support our evidence that there is a negative association between faultline strength in the board of directors and SED. Our set of sensitivity tests documents that our inferences are robust and not subject to possible endogeneity problems. Table 10 further suggests that analyst coverage can play as effective mechanism to mitigate the negative association between faultline strength in the board of directors and SED.

5 Conclusion

This paper contributes to the literature on diversity and social and environmental disclosures by examining the influence of faultline strength, that splits a boardroom into relatively homogeneous subgroups based on directors’ diversified attributes, on social and environmental disclosures. To gauge social and environmental disclosures, we create a comprehensive corporate social- and environmental-related lexicon capturing the information conveyed in annual report narratives. Using a sample of FTSE All-share non-financial firms, our results show that firms with higher faultline strength in the boardroom (i.e., relatively more homogeneous subgroups) exhibit significantly lower levels of both social and environmental disclosures in their narrative sections of annual reports. This implies that board diversity faultlines are likely to have a detrimental effect on corporate boards regarding reaching a consensus decision on disclosing information on social and environmental aspects. Our results remain robust after various sensitivity tests and addressing potential endogeneity problems. Our results provide timely evidence-based insights into major recent structural reforms aiming at proposing remedies to corporate governance problems in the UK, specifically that interest should not be confined to board diversity per se but configurations (the extent of convergence) between the diversified attributes. Furthermore, the evidence provided by our paper should be of interest to the UK’s regulatory bodies (Financial Reporting Council) considering their increasing focus and pursuit to understand the underlying challenges of corporate social and environmental reporting. A fruitful expansion of the present study would be to examine how board diversity faultlines are likely to affect social and environmental disclosures during periods of crisis such as Brexit and the pandemic.

Notes

Throughout the paper, we use the terms “diversity faultlines” and “faultlines” interchangeably. Refer to Appendix 1 for an illustrative example on how faultlines can be constituted on the board.

Meyer and Glenz (2013) review and show the limitations of the available faultline measures. Then, they propose a new and the most accurate faultline measure, using a cluster-based approach, average silhouette width (ASW), that identifies the number of subgroups and subgroup membership. Importantly, they indicate that this advantageous measure is suitable to measure the faultline strength on the boards of directors. Refer to Meyer and Glenz (2013) for further details.

As noted earlier, Meyer and Glenz (2013) review and show the limitations of the available faultline measures. Then, they propose a new and the most accurate faultline measure, using a cluster-based approach, average silhouette width (ASW), that identifies the number of subgroups and subgroup membership. Importantly, they indicate that this advantageous measure is suitable to measure the faultline strength on the boards of directors. Refer to Appendix 1 for further details on faultline computation.

Throughout our regressions, we evaluate the effects of multicollinearity by calculating the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for each independent variable. With VIFs less than 10, we conclude that multicollinearity is not a concern in our analyses.

Notably, the observed increase in some coefficient estimates is in line with prior research suggesting possible stronger estimates from analysis using instrumental variables (e.g., Elamer et al. 2021).

Consequently, the slope dummy control variable (ESSI) is dropped from this test.

References

Adams RB, Hermalin BE, Weisbach MS (2010) The role of boards of directors in corporate governance: a conceptual framework and survey. J Econ Lit 48(1):58–107. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.48.1.58

Adams RB, Akyol AC, Verwijmeren P (2018) Director skill sets. J Financ Econ 130(3):641–662

Aguilera RV, Marano V, Haxhi I (2019) International corporate governance: a review and opportunities for future research. J Int Bus Stud 50(4):457–498. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00232-w

Albertini E (2014) A descriptive analysis of environmental disclosure: a longitudinal study of french companies. J Bus Ethics 121(2):233–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1698-y

Al-Shaer H, Albitar K, Liu J (2023) CEO power and CSR-linked compensation for corporate environmental responsibility: UK evidence. Rev Quant Financ Acc 60(3):1025–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01118-z

Arena C, Garcia-Torea N, Michelon G (2024) The lines that divide: board demographic faultlines and proactive environmental strategy. Corp Gov Int Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12570

Backes-Gellner U, Veen S (2013) Positive effects of ageing and age diversity in innovative companies—large-scale empirical evidence on company productivity. Hum Resour Manag J 23(3):279–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12011

Bassyouny H, Abdelfattah T, Tao L (2022) Narrative disclosure tone: A review and areas for future research. J Int Account Audit Tax. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2022.100511

Bear S, Rahman N, Post C (2010) The impact of board diversity and gender composition on corporate social responsibility and firm reputation. J Bus Ethics 97(2):207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0505-2

BEIS SC (2019) The Future of audit. London, England: House of Commons of the United Kingdom. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmbeis/1718/1718.pdf

Bell ST, Villado AJ, Lukasik MA, Belau L, Briggs AL (2011) Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: a meta-analysis. J Manag 37(3):709–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365001

Ben-Amar W, Chang M, McIlkenny P (2017) Board gender diversity and corporate response to sustainability initiatives: evidence from the carbon disclosure project. J Bus Ethics 142(2):369–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2759-1

Blankespoor E, Miller GS, White HD (2014) The Role of Dissemination in Market Liquidity: evidence from Firms’ Use of Twitter™. Account Rev 89(1):79–112

Botosan CA (1997) Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. Account Rev 72:323–349

Brydon (2019) Report of the independent review into the quality and effectiveness of audit. Financial Services Monitor Worldwide. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-quality-and-effectiveness-of-audit-independent-review

Bunderson JS, Sutcliffe KM (2002) Comparing alternative conceptualizations of functional diversity in management teams: process and performance effects. Acad Manag J 45(5):875–893. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069319

Bushman R, Chen Q, Engel E, Smith A (2004) Financial accounting information, organizational complexity and corporate governance systems. J Account Econ 37(2):167–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2003.09.005

Byron K, Post C (2016) Women on boards of directors and corporate social performance: a meta-analysis. Corp Gov Int Rev 24(4):428–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12165

Cabeza-García L, Fernández-Gago R, Nieto M (2018) Do board gender diversity and director typology impact csr reporting? Eur Manag Rev 15(4):559–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12143

Cao J, Ellis KM, Li M (2019) Inside the board room: the influence of nationality and cultural diversity on cross-border merger and acquisition outcomes. Rev Quant Financ Acc 53:1031–1068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0774-x

Chen IJ, Lin WC, Lo HC, Chen SS (2023) Board diversity and corporate innovation. Rev Quant Financ Account. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-023-01145-4

Clatworthy M, Jones MJ (2003) Financial reporting of good news and bad news: evidence from accounting narratives. Account Bus Res 33(3):171–185

CMA CAMA (2019) Statutory audit market study. https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/statutory-audit-market-study

Cole BM, Salimath MS (2013) Diversity identity management: an organizational perspective. J Bus Ethics 116(1):151–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1466-4

Correia MM (2014) Political connections and SEC enforcement. J Account Econ 57(2–3):241–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.04.004

Das Neves JC, Melé D (2013) Managing ethically cultural diversity: learning from Thomas Aquinas. J Bus Ethics 116(4):769–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1820-1

De Villiers C, Marques A (2016) Corporate social responsibility, country-level predispositions, and the consequences of choosing a level of disclosure. Account Bus Res 46(2):167–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2015.1039476

Defond ML, Hann RN, Hu X (2005) Does the market value financial expertise on audit committees of boards of directors? J Account Res 43(2):153–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2005.00166.x

DeFond ML, Hung M, Li S, Li Y (2015) Does mandatory IFRS adoption affect crash risk? Account Rev 90(1):265–299

Desender KA, LópezPuertas-Lamy M, Pattitoni P, Petracci B (2020) Corporate social responsibility and cost of financing—the importance of the international corporate governance system. Corp Gov Int Rev 28(3):207–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12312

Donelson DC, Ege MS, McInnis JM (2017) Internal control weaknesses and financial reporting fraud. Audit J Pract Theory 36(3):45–69. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51608

Elamer AA, Ntim CG, Abdou HA, Owusu A, Elmagrhi M, Ibrahim AEA (2021) Are bank risk disclosures informative? Evidence from debt markets. Int J Financ Econ 26(1):1270–1298. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1849

Ellis KM, Keys PY (2015) Workforce diversity and shareholder value: a multi-level perspective. Rev Quant Financ Acc 44:191–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-013-0403-7

Elsayed M, Elshandidy T (2020) Do narrative-related disclosures predict corporate failure? Evidence from UK non-financial publicly quoted firms. Int Rev Financ Anal 71:101555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101555

Elsayed M, Elshandidy T (2021) Internal control effectiveness, textual risk disclosure, and their usefulness: U.S. evidence. Adv Account 53:100531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2021.100531

Elsayed M, Elshandidy T, Ahmed Y (2022) Corporate failure in the UK: an examination of corporate governance reforms. Int Rev Finan Anal 82:102165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102165

Elsayed M, Elshandidy T, Ahmed Y (2023) Is expanded auditor reporting meaningful? UK evidence. J Int Account Audit Tax 53:100582

Elshandidy T, Shrives PJ (2016) Environmental incentives for and usefulness of textual risk reporting: Evidence from Germany. Int J Account 51(4):464–486

Elshandidy T, Bamber M, Omara H (2024) Across the faultlines: a multi-dimensional index to measure and assess board diversity. Int Rev Financ Anal 93:103231

Environmental Reporting Guidelines. (2019) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-quality-and-effectiveness-of-audit-independent-review

Fakoya MB, Lawal AB (2020) Effect of environmental accounting on the quality of accounting disclosures of shipping firms in Nigeria. J Account Manag, 10(1)

Fama EF (1980) Agency problems and the theory of the firm. J Polit Econ 88(2):288–307

Farrell KA, Hersch PL (2005) Additions to corporate boards: the effect of gender. J Corp Finan 11(1–2):85–106

Fedaseyeu V, Linck JS, Wagner HF (2018) Do qualifications matter? New evidence on board functions and director compensation. J Corp Finan 48:816–839

Feng M, Li C, McVay S (2009) Internal control and management guidance. J Account Econ 48(2):190–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.09.004

Forbes DP, Milliken FJ (1999) Cognition and corporate governance: understanding boards of directors as strategic decision-making groups. Acad Manag Rev 24(3):489–505

Forbes (2019) Is Brexit good or bad news for workplace diversity and inclusion?. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bonniechiu/2019/01/30/is-brexit-good-or-bad-news-for-workplace-diversity-and-inclusion/

Francis B, Hasan I, Wu Q (2015) Professors in the boardroom and their impact on corporate governance and firm performance. Financ Manag 44(3):547–581

FRC (2018) The UK corporate governance code (0012–3242). Financial Reporting Council. https://www.frc.org.uk/news/july-2018/a-uk-corporate-governance-code-that-is-fit-for-the

FRC (2020) Guidance for companies on corporate governance and reporting (COVID-19). Financial Reporting Council. https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/faae2ec8-5b40-4838-8a17-a7b93493ff4c/Company-Guidance-Covid-19-Updated-December-2020.pdf

Galbreath J (2011) Are there gender-related influences on corporate sustainability? A study of women on boards of directors. J Manag Organ 17(1):17–38. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2011.17.1.17

Galbreath J (2016) When do board and management resources complement each other? A Study of effects on corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 136(2):281–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2519-7

Gamerschlag R (2013) Value relevance of human capital information. J Intellect Cap 14(2):325–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691931311323913

Gamerschlag R, Möller K, Verbeeten F (2011) Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: empirical evidence from Germany. RMS 5(2):233–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-010-0052-3

Gantyowati E, Agustine KF (2017) Firm’s characteristics and csr disclosure, Indonesia and Malaysia Cases. Rev Integr Bus Econ Res 6(3):131

Ge R, Lennox C (2011) Do acquirers disclose good news or withhold bad news when they finance their acquisitions using equity? Rev Acc Stud 16(1):183–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-010-9139-y

Gibson K, O’Donovan G (2007) Corporate governance and environmental reporting: an Australian study. Corp Gov Int Rev 15(5):944–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2007.00615.x

Gregory A, Tharyan R, Whittaker J (2014) Corporate social responsibility and firm value: disaggregating the effects on cash flow, risk and growth. J Bus Ethics 124(4):633–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1898-5

GRI standards 305 (2016) https://www.globalreporting.org/pdf.ashx?id=12510&page=16

Guillaume YRF, Brodbeck FC, Riketta M (2012) Surface- and deep-level dissimilarity effects on social integration and individual effectiveness related outcomes in work groups: a meta-analytic integration. J Occup Organ Psychol 85(1):80–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02005.x

Gupta PP, Sami H, Zhou H (2018) Do companies with effective internal controls over financial reporting benefit from Sarbanes-Oxley sections 302 and 404?. J Account Audit Financ 33(2):200–227

Haniffa RM, Cooke TE (2005) The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. J Account Public Policy 24(5):391–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2005.06.001

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352

Hoang TC, Abeysekera I, Ma S (2018a) Board diversity and corporate social disclosure: evidence from Vietnam. J Bus Ethics 151(3):833–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3260-1

Hoang TC, Abeysekera I, Ma S (2018) Board diversity and corporate social disclosure: evidence from Vietnam. J Bus Ethics 151:833–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3260-1

Horwitz SK, Horwitz IB (2007) The effects of team diversity on team outcomes: a meta-analytic review of team demography, vol 33. Sage Publications, Los Angeles, CA, pp 987–1015

Hsu A, Koh K, Liu S, Tong YH (2017) Corporate social responsibility and corporate disclosures: an investigation of investors’ and analysts’ perceptions. J Bus Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3767-0

Huang S, Hilary G (2018) Zombie board: Board tenure and firm performance. J Account Res 56(4):1285–1329

ICAEW library of environmental, social and sustainability reporting (2020) https://www.icaew.com/library/subject-gateways/environment-and-sustainability/environmental-social-and-sustainability-reporting

Jackson G, Bartosch J, Avetisyan E, Kinderman D, Knudsen JS (2019) Mandatory non-financial disclosure and its influence on CSR: an international comparison. J Bus Ethics 162(2):323–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04200-0

Jaeger AM, Kim SS, Butt AN (2016) Leveraging values diversity: the emergence and implications of a global managerial culture in global organizations. Manag Int Rev 56(2):227–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-015-0274-3

Jain T, Jamali D (2016) Looking inside the black box: the effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Corp Gov Int Rev 24(3):253–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12154

Jia N (2017) Should directors have term limits?–Evidence from corporate innovation. Euro Account Rev 26(4):755–785

Jizi M (2017) The influence of board composition on sustainable development disclosure. Bus Strateg Environ 26(5):640–655. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1943

Joshi A, Roh H (2009) The role of context in work team diversity research: a meta-analytic review. Acad Manag J 52(3):599–627. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2009.41331491

Karim ATME, Albitar K, Elmarzouky M (2021) A novel measure of corporate carbon emission disclosure, the effect of capital expenditures and corporate governance. J Environ Manage 290:112581–112581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112581

Katmon N, Farooque OA (2017) Exploring the impact of internal corporate governance on the relation between disclosure quality and earnings management in the UK listed companies. J Bus Ethics 142(2):345–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2752-8

Katmon N, Mohamad ZZ, Norwani NM, Farooque OA (2019) Comprehensive board diversity and quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from an emerging market. J Bus Ethics 157(2):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3672-6

Khan A, Muttakin MB, Siddiqui J (2013) Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: evidence from an emerging economy. J Bus Ethics 114(2):207–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1336-0

Kim K, Mauldin E, Patro S (2014) Outside directors and board advising and monitoring performance. J Account Econ 57(2–3):110–131

Kravet T, Muslu V (2013) Textual risk disclosures and investors’ risk perceptions. Rev Acc Stud 18(4):1088–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9228-9

Larcker DF, Rusticus TO (2010) On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. J Account Econ 49(3):186–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.11.004

Lau DC, Murnighan JK (1998) Demographic diversity and faultlines: the compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Acad Manag Rev 23(2):325–340. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1998.533229

Lau DC, Murnighan JK (2005) Interactions within groups and subgroups: the effects of demographic faultlines. Acad Manag J 48(4):645–659. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2005.17843943

Lau C, Lu Y, Liang Q (2016) Corporate social responsibility in china: a corporate governance approach. J Bus Ethics 136(1):73–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2513-0

Lee K-H, Barker M, Mouasher A (2013) Is it even espoused? An exploratory study of commitment to sustainability as evidenced in vision, mission, and graduate attribute statements in Australian universities. J Clean Prod 48:20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.01.007

Lennox CS, Schmidt JJ, Thompson AM (2023) Why are expanded audit reports not informative to investors? Evidence from the United Kingdom. Rev Acc Stud 28(2):497–532

Li Z, Wang B, Zhou D (2022) Financial experts of top management teams and corporate social responsibility: evidence from China. Rev Quant Financ Acc 59(4):1335–1386

Liao L, Luo L, Tang Q (2015) Gender diversity, board independence, environmental committee and greenhouse gas disclosure. Br Account Rev 47(4):409–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2014.01.002

Loughran TIM, McDonald B (2011) When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. J Financ 66(1):35–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01625.x

Loughran TIM, McDonald B (2016) Textual Analysis in accounting and finance: a survey. J Account Res 54(4):1187–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12123

Ma Y, Zhang Q, Yin Q (2021) Top management team faultlines, green technology innovation and firm financial performance. J Environ Manage 285:112095–112095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112095

Mallin C, Michelon G, Raggi D (2013) Monitoring intensity and stakeholders’ orientation: How does governance affect social and environmental disclosure? J Bus Ethics 114(1):29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1324-4

Mallin C, Farag H, Ow-Yong K (2014) Corporate social responsibility and financial performance in Islamic banks. J Econ Behav Organ 103:S21–S38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.03.001

McGuinness PB, Vieito JP, Wang M (2017) The role of board gender and foreign ownership in the CSR performance of Chinese listed firms. J Corp Finan 42:75–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.11.001

McIntyre ML, Murphy SA, Mitchell P (2007) The top team: examining board composition and firm performance. Corp Gov Int J Bus Soc 7(5):547–561

Mekhaimer M, Abakah AA, Ibrahim A, Hussainey K (2022) Subordinate executives’ horizon and firm policies. J Corp Financ 74:102220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2022.102220

Meyer B, Glenz A (2013) Team faultline measures: a computational comparison and a new approach to multiple subgroups. Organ Res Methods 16(3):393–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428113484970

Michelon G, Parbonetti A (2012) The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. J Manage Gov 16(3):477–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-010-9160-3

Michelon G, Pilonato S, Ricceri F (2015) CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: an empirical analysis. Crit Perspect Account 33:59–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.10.003

Miller BP (2010) The effects of reporting complexity on small and large investor trading. Account Rev 85(6):2107–2143

Milne MJ, Gray R (2013) W(h)ither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. J Bus Ethics 118(1):13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1543-8

Muslu V, Mutlu S, Radhakrishnan S, Tsang A (2019) Corporate social responsibility report narratives and analyst forecast accuracy. J Bus Ethics 154(4):1119–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3429-7

Nadeem M (2020) Does board gender diversity influence voluntary disclosure of intellectual capital in initial public offering prospectuses? Evidence from China. Corp Gov Int Rev 28(2):100–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12304

Nekhili M, Nagati H, Chtioui T, Nekhili A (2017) Gender-diverse board and the relevance of voluntary CSR reporting. Int Rev Financ Anal 50:81–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2017.02.003

Parker SJ (2016) Report into ethnic diversity of UK boards recommends FTSE 100s go “Beyond One by ‘21”. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ethnic-diversity-of-uk-boards-the-parker-review

Parliament UK (2021) Brexit timeline: events leading to the UK’s exit from the European Union. House of Commons Library. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7960/CBP-7960.pdf

Pfeffer J, Salancik GR (1978) The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. Harper & Row, New York

Porumb VA, Zengin-Karaibrahimoglu Y, Lobo GJ, Hooghiemstra R, De Waard D (2021) Expanded auditor’s report disclosures and loan contracting. Contemp Account Res 38(4):3214–3253

Post C, Rahman N, Rubow E (2011) Green governance: boards of directors’ composition and environmental corporate social responsibility. Bus Soc 50(1):189–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650310394642

Post C, Rahman N, McQuillen C (2015) From board composition to corporate environmental performance through sustainability-themed alliances. J Bus Ethics 130(2):423–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2231-7

Qiu Y, Shaukat A, Tharyan R (2016) Environmental and social disclosures: link with corporate financial performance. Br Account Rev 48(1):102–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2014.10.007

Rao K, Tilt C (2016) Board composition and corporate social responsibility: the role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. J Bus Ethics 138(2):327–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2613-5

Rosenblum D, Nili Y (2019) Board diversity by term limits. Alabama Law Rev 71(1):211–260

Schmid T, Ampenberger M, Kaserer C, Achleitner A-K (2015) Family firm heterogeneity and corporate policy: evidence from diversification decisions. Corp Gov Int Rev 23(3):285–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12091

Schneid M, Isidor R, Steinmetz H, Kabst R (2016) Age diversity and team outcomes: a quantitative review. J Manag Psychol 31(1):2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-07-2012-0228

Shaukat A, Qiu Y, Trojanowski G (2016) Board attributes, corporate social responsibility strategy, and corporate environmental and social performance. J Bus Ethics 135(3):569–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2460-9

Singh V, Vinnicombe S, Johnson P (2001) Women directors on top UK boards. Corp Gov Int Rev 9(3):206–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8683.00248

Stock JH, Wright JH, Yogo M (2002) A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. J Bus Econ Stat 20(4):518–529

Tauringana V, Chithambo L (2015) The effect of DEFRA guidance on greenhouse gas disclosure. Br Account Rev 47(4):425–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2014.07.002

Terjesen S, Sealy R, Singh V (2009) Women directors on corporate boards: a review and research agenda. Corp Gov Int Rev 17(3):320–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00742.x

Thatcher SMB, Patel PC (2011) Demographic faultlines: a meta-analysis of the literature. J Appl Psychol 96(6):1119–1139. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024167

Thatcher SMB, Patel PC (2012) Group faultlines: A review, integration, and guide to future research. J Manag 38(4):969–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311426187

Torreggiani G, De Giacomo MR (2022) CSR representation in the public discourse and corporate environmental disclosure strategies in the context of Brexit. A cross-country study of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. J Clean Prod 367:132783

Trinh VQ, Salama A, Li T, Lyu O, Papagiannidis S (2023) Former CEOs chairing the board: does it matter to corporate social and environmental investments? Rev Quant Financ Account. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-023-01184-x

Van Knippenberg D, Dawson JF, West MA, Homan AC (2011) Diversity faultlines, shared objectives, and top management team performance. Hum Relat 64(3):307–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710378384

Van Peteghem M, Bruynseels L, Gaeremynck A (2018) Beyond diversity: a tale of faultlines and frictions. Account Rev 93(2):339–367

Ward JH Jr (1963) Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc 58(301):236–244

Wu JD (2013) Diverse institutional environments and product innovation of emerging market firms. Manag Int Rev 53(1):39–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-012-0162-z

Xing L, Gonzalez A, Sila V (2021) Does cooperation among women enhance or impede firm performance? Br Account Rev 53(4):100936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2020.100936

Xue S, Tang Y, Xu Y, Ling CD, Xie XY, Mo S (2024) How boards’ factional faultlines affect corporate financial fraud. Asia Pac J Manag 41(1):351–376

Yu H-C, Kuo L, Kao M-F (2017) The relationship between CSR disclosure and competitive advantage. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 8(5):547–570. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-11-2016-0086

Zhang R, Li B (2024) Board team faultlines and enterprise innovation investment. Financ Res Lett 66:105601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105601

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank the Editor (Prof. Cheng-Few Lee) and two anonymous referees for their constructive feedback. The paper has benefited from useful comments and suggestions from research seminar participants at Bristol Business School, University of West of England, UK; the University of Northampton’s Business School, UK; College of Business Administration, Ajman University, UAE. We thank Mark Baimbridge, Salma Ibrahim, Yousry Ahmed, and Moataz Elmassri for their helpful suggestions. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Director | Age | Gender | Nationality |

|---|---|---|---|

A | 55 | Female | British |

B | 35 | Male | British |

C | 55 | Male | French |

D | 35 | Female | French |

This appendix provides an illustrative example on how faultlines can be emerged across our paper’s diversity attributes (age, gender, and nationality) for a board that has four members, for simplicity. Thus, we provide the following scenarios:

-

Potential faultlines could form along the lines of age, gender, and nationality. One possible faultline might divide the group based on age and nationality: the older British Director (A) and the younger British director (B) might form one subgroup, while the older French director (C) and the younger French Director (D) might form another.

-

When looking at nationality alone, Directors A and B (both British) might align against Directors C and D (both French), despite their gender and age differences. National culture could strongly influence their values and decision-making styles, potentially leading to a national faultline within the board.

-

Another faultline might emerge along gender lines, where Directors A and D (both females) form one subgroup, and Directors B and C (both males) form another, potentially leading to gender-based subgroups. These subgroups could influence the dynamics of board interactions and decision-making processes.

-

Similarly, Directors A and C share the same age but differ in gender and nationality, which might align them on certain issues related to experience but distinct them on others related to cultural or gender perspectives.

Accordingly, this example clearly shows that faultlines and conventional diversity are different constructs. This example applies to all real-life companies across board of directors’ different attributes. For example, a summary of real board of directors attributes for three UK firms in 2005 and 2018 is as follows:

Company | Year | Avg. Age | Gender distribution | Nationality distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc | 2005 | 67.5 | 5M, 1F | All British |

2018 | 62.7 | 7M, 2F | All British | |

Costain group Plc | 2005 | 69.7 | All Male | 4 British, 1 Malaysian, 1 Egyptian, 1 Australian |

2018 | 59.7 | 5M, 3F | All British | |

Croda international Plc | 2005 | 67.4 | 4M, 1F | All British |

2018 | 58.1 | 7M, 3F | 9 British, 1 Swiss |

In terms of faultlines computation, as discussed in Sect. 3. Research design, we utilize the most versatile and accurate measure for faultline strength proposed by Meyer and Glenz (2013), namely the average silhouette width (ASW), that identifies the number of subgroups and subgroup membership considering within-subgroup homogeneity and between subgroup separation. In this, the computation of ASW is based on two steps: (1) using a cluster-analytic algorithm that identifies subgroups utilizing Ward’s algorithm (Ward 1963) and the average linkage strategy; (2) identifying the optimal subgroup classification for the possibilities identified in the first step by defining the maximum ASW for each group. Now, let us assume that we have a board of directors divided into two subgroups: X and Y. Then, the ASW is the average of individual silhouette widths for all board of directors, i.e., assessing how well a director fits into subgroup X compared with subgroup Y. The individual silhouette width can be identified by the following equation:

where \({a}_{i}\) denotes the average dissimilarity of i to all directors of subgroup X and \({b}_{i}\) denotes the average dissimilarity of i and all directors of subgroup Y using Euclidean distances between directors to calculate dissimilarities. A higher \(s\left(i\right)\) denotes that board member has a stronger association in the subgroup. Then, ASW measures the cluster solution for the whole board by capturing the highest ASW value obtained after performing an iterative process as the optimal solution for capturing faultline strength. As mentioned earlier in the paper, we employ the free open-source statistical environment R (R Development Core Team, 2012) provided by Meyer and Glenz (2013), available at http://www.group-faultlines.org, to calculate our faultline measure using age, gender, and nationality attributes of directors on the board of directors.

Appendix 2

2.1 Variable definitions

Variable | Definition and measures | Data source |

|---|---|---|

Social and environmental disclosure (SED) | All social and environmental information that is exhibited in the annual report narrative sections. The score is the percentage of the number of words indicating SED in the annual report narrative sections divided by the total number of words in the annual report narrative sections. Textual analysis is processed using Diction 7 software employing the wordlist given in Appendix 3. The textual analysis is used to further identify the SED categories as introduced below. Data source is Annual report | Annual report |

Environmental disclosure (ED) | All feasible information that exhibits environmental disclosure in the annual report narrative sections. The score is the percentage of the number of words indicating ED in the annual report narrative sections divided by the total number of words in the annual report narrative sections | Annual report |