Abstract

This paper examines how CEO power and CSR-linked compensation influences environmental performance. We investigate the role of CEO managerial power (proxied by CEO duality and the presence of executive directors on the board), and CEO legitimate power (proxied by CEO tenure), adopting three measures of environmental performance, including the environmental scores, carbon emission scores and a composite index assessing the level of a firm’s engagement in several environmental practices. Analysing a sample of FTSE-All-Share companies for the period 2011–2019, we find that CEOs who receive compensation from engagement in environmental activities are motivated to improve environmental performance. Moreover, newly appointed CEOs engage more in environmental initiatives, suggesting that they use it as a signal to mitigate career concerns in their early tenure, whereas CEOs with managerial power engage less in environmental projects due to the costs associated with them. These effects are stronger in firms with independent and diverse boards, firms operating in the environmentally sensitive sectors and non-loss-making firms. This study provides original evidence of the role of environmental-linked incentives and managerial power in managing environmental impact and optimising the environmental performance of their companies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporate success depends primarily upon cutting-edge strategies and focused marketing (Groysberg et al. 2018), but the current political climate also requires business leaders to be socially aware as well as commercially astute. Research demonstrates that a commitment to corporate social responsibility (CSR) can attract investment, strengthen engagement with stakeholders, and build a more sustainable and resilient business (Lu et al. 2021). In particular, CEOs must fulfil a vital aspect of their fiduciary duty by ensuring that a company’s negative externalities do not degrade the environment or contribute to global warming.Footnote 1 Whereas once senior managers focused on profits and shareholders’ returns, now they must recognise their social responsibilities towards all stakeholders, both internal and external, by establishing quantifiable goals for GHG emissions, minimising their companies’ carbon footprints, and reducing water and paper consumption (Walls and Berrone 2015; Haque 2017). CEOs are under growing pressure from regulators, investors, environmental groups, and other stakeholders to institute corporate reforms that will make a positive contribution to countering the dystopian consequences of climate change. In this study, we examine how CEO power and CSR-linked compensation influence managerial CSR decisions and corporate environmental performance.

A recent survey, undertaken by KPMG on CEO Outlook, reveals that 86% of UK CEOs recognise the vital importance of engaging in responsible business practices, establishing strong ESGFootnote 2 credentials, and seeking an understanding of the needs of diverse stakeholders.Footnote 3 Incorporating CSR-related targets into executive compensation packages enables companies to attract and retain the best leaders while building sustainable value. Clearly, the selection of individuals sympathetic towards the ideals of CSR is critical to corporate success in the modern world, as the power vested in a CEO can have significant consequences for long-term institutional strategies. This analysis therefore examines how CEO power and CSR-linked compensations influence strategic development in terms of environmental performance.

Our investigation examines two sources of power: CEO managerial power, in relation to which we consider CEO duality and the percentage of executive directors on a board (Rashid et al. 2020; Garcia-Sanchez et al. 2020); and CEO legitimate power, for which we use CEO tenure as our measure (Walls and Berrone 2017). In this study, we explore the role of power and CSR related incentives to explain the link between CEO leadership and corporate environmental responsibility (CER) in the UK institutional context.

Analysing a sample of FTSE-All-Share for the period 2011–2019, we establish that CEO power and CSR-linked compensation are important factors in relation to environmental performance. CEOs who are given incentives for engaging in environmental activities are more likely to improve environmental performance. Conversely, a CEOs’ legitimate managerial powers are significantly and negatively associated with environmental performance, suggesting that CEOs who hold greater authority, and have longer tenures, are more resistant to change. Consequently, they might not emphasize their pursuit of new environmental initiatives; while newly appointed CEOs use their engagement in environmental enterprises as a signal to mitigate career concerns at the outset of their tenure (Chen et al. 2019), being more willing to experiment and pursue ecological objectives.

We perform robustness tests and conduct sub-sample analyses in respect of board diversity and board independence, our finding shows that the observed relationships are more pronounced in firms with independent and diverse boards. Notably, newly appointed CEOs’ incentives to signal their environmental credentials are stronger when corporate boards are diverse and independent. However, when a board is less independent and comprises of a higher proportion of male directors, CEOs can use their powers to act opportunistically and make investment decisions that increase shareholders’ returns with less board opposition. We further explore how companies in environmentally sensitive industries, as opposed to companies not in environmentally sensitive industries, cause the influence of CEO variables to change. The results are consistent with the main findings in relation to companies trading in sustainability-sensitive industries. Finally, when dividing the sample into loss-making and non-loss-making firms, we find that CEOs are less likely to undertake environmental developments when their firms are enduring losses, suggesting that CEOs who have power over the top management team are less likely to engage in costly environmental developments when their firms are enduring losses. When we address the endogeneity issue by employing the GMM and 2SLS estimators (with IVs), and PSM and Heckman two-stage estimation, the results still hold.

The present study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, unlike prior research, which is heavily focused on overall CSR performance, we examine the influence of CSR sub-categories e.g., the environment, which is not commonly afforded comprehensive consideration (Velte 2020). Further, we scrutinise various proxies for environmental performance, including environmental scores and carbon emission scores. Notably, we construct a composite index to reflect the level of a firm’s engagement in several environmental practices, including the creation of an emission target, the purchase or production of carbon credits, the reporting of environmental lawsuits, and the receipt of ISO 14000 certification for better environmental impact management. This enables us to derive consistent results on CEO power and CSR related incentives, and to evaluate the role that they can play in enhancing firms’ legitimacy regarding environmental performance.

Second, our study augments the debate on factors that drive corporate environmental performance by highlighting CSR-linked compensation as a new dimension of this phenomenon. Unlike existing studies, which focus on CEO monetary compensation regarding the CEO compensation-CSR nexus (e.g., Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009; Callan and Thomas 2011, 2014; Ibrahim et al. 2021), we specifically investigate the impact of CSR-linked compensation on environmental performance. Moreover, our investigation differs from the few studies undertaken that highlight the importance of CSR-related targets in executive compensation contracts using content analysis and case study approaches (Maas and Rosendaal 2016; Kolk and Perego 2014). These studies do not, as ours does, empirically investigate the association between CSR-linked compensation and environmental performance. It is also different from Al-Shaer and Zaman’s (2019) study, which investigates the impact of sustainability-linked compensation on sustainability reporting assurance.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the hypotheses. Section 3 discusses the research design, including data and sample, variable measurement, and model specifications. Section 4 reports and discusses the findings. Section 5 concludes the study.

2 Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1 CSR-linked CEO compensation and environmental performance

Stakeholder theory proposes that firms should satisfy the needs of stakeholders by enhancing their social and environmental performance (Freeman 1984). The extent of managers’ attention to stakeholders’ demands depends largely on their incentives and interests. Companies in response to stakeholders’ pressures, include non-financial metrics in CEO compensation, holding them accountable for their eco-friendly behaviour, and consequently their impact on sustainable performance (Al-Shaer and Zaman 2019).

Prior literature examines the impact of CEO incentives, in particular monetary compensation-, on CSR performance, and demonstrates that CEO compensation engenders increased CSR performance (e.g., Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009; Callan and Thomas 2011, 2014; Hong et al. 2016; Karim et al. 2018). However, some studies report a negative association between CEO compensation and social performance (e.g., Deckop et al. 2006; Cai et al. 2011; Rekker et al. 2014; Francoeur et al. 2017). A few studies emphasise the importance of CSR-related targets in executive compensation contracts in different contexts (Maas and Rosendaal 2016), examining the integration of sustainability targets in executive remuneration of companies from different countries. Further, Kolk and Perego (2014) investigate the introduction of sustainability related bonuses using four case studies from the Netherlands, while Al-Shaer and Zaman (2019) investigate the impact of sustainability-linked compensation on sustainability reporting assurance. These studies contend that companies that include sustainability terms in compensation contracts are likely to enhance CSR performance, as CEOs can then be held accountable for their inaction (Maas and Rosendaal 2016). Hence, companies need to link CSR related provisions in CEOs’ compensation contracts to motivate CEOs to enhance their companies’ social and environmental performance (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009). Baraibar‐Diez et al. (2019) argue that CEOs’ compensation serves as a motivational tool that helps CEOs to act in accordance with the interests of stakeholders (Devers et al. 2007). Compensating CEOs for the adoption of long-term environmental strategies helps to promote responsible behaviour and achieve better environmental performance (Haque 2017; Baraibar‐Diez et al. 2019). Given the foregoing discussion, we argue that an executive reward policy linked with CER is likely to have a positive impact on corporate strategies related to the environment, and propose our first hypothesis below:

H1

CSR-linked CEO compensation is positively associated with environmental performance.

2.2 CEO power and environmental performance

2.2.1 CEO managerial power and environmental performance

From a theoretical perspective, managerial effort is unobservable, leaving powerful CEOs free to pursue their own objectives at the expense of shareholders’ interests (Fama and Jensen 1983; Tan and Liu 2016). Managerial power theory conceptualizes such actions as discretionary and opportunistic behaviour in conflict with stakeholders’ needs (Bebchuk and Fried 2006). Therefore, dominant CEOs may decide not to undertake environmental projects because of the costs involved and suboptimal value maximisation (Rashid et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2021). Conversely, if a CEO acts in a stewardship capacity, safeguarding the firm and the ecosystem, a firms’ environmental practices and innovations will be enhanced (Davis et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 2021; Shui et al. 2022). However, the motivation for adopting beneficial social and environmental practices may also be opportunistic, since this will redound to the image and reputation of a CEO (Li et al. 2018). Hence, a powerful CEO might pursue "pet" projects to improve their public image as a champion of the environment, regardless of the negative impact on shareholder value.

Thus, CEO power is a crucial factor that affects corporate decisions related to social and environmental activities. Prior literature discusses two sources of power: CEO managerial power over the board and CEO legitimate power (Walls and Berrone, 2017; Muttakin et al. 2018; Rashid et al. 2020; Garcia-Sanchez et al. 2020). Extant research offers mixed evidence on the relationship between CEO managerial power and social performance, with some studies demonstrating that CEO managerial power negatively influences CSR performance (Li et al. 2016; Muttakin et al. 2018; Sheikh 2019). Powerful CEOs may consider that excessive commitments to CSR practices will reduce shareholders’ wealth, in particular in emerging markets (Muttakin et al. 2018). Other studies report that powerful CEOs enhance transparency and the implementation of CSR (e.g., Fabrizi et al. 2014; Jizi et al. 2014).

Prior studies that use CEO duality as a dimension of CEO managerial power to examine its impact on CSR performance provide mixed evidence on the relationship between CEO duality and social performance. CEO duality refers to whether the CEO and the chairman positions are combined, and it reflects the power exerted by the CEO which can affect corporate performance. Jizi et al. (2014) show that CEO duality has a positive impact on CSR performance; in contrast, Mallin and Michelon (2011) suggest a negative influence of CEO duality on corporate social performance, while Haque (2017) finds no evidence of any impact of CEO duality on carbon performance. Moreover, the level of power that a CEO wields within an organisation depends on his or her relative influence over the executive board (Walls and Berrone 2017). The presence of executive members on the board also strengthens CEO managerial power by reducing the degree of board independence (Garcia-Sanchez et al. 2020). As a result, when there is a larger proportion of executive directors on a board, CEOs become more powerful and enjoy more influence over investment decisions at the expense of shareholders' interests (Sheikh, 2019). The foregoing arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

H2

CEO managerial power is associated with environmental performance.

2.2.2 CEO legitimate power and environmental performance

CEO legitimate power plays a crucial role in the development of corporate strategies and decision-making processes. CEOs have a greater ability to influence their companies’ environmental practices when they have experience in addressing environmental issues (Walls and Berrone 2017). From the agency costs perspective, longer tenure may reflect well established managers who are more likely to focus on maximising their own interests by promoting executives who share similar ideas (Berger et al. 1997; Schulze et al. 2001; Lewis et al. 2014; Tan and Liu, 2016). Based on the career concern hypothesis of CSR, newly appointed CEOs are more likely to mitigate career concerns in the early years of their service by engaging more in social and environmental initiatives that create long-term sustainable value for their stakeholders (Chen et al. 2019). CEOs not only need to undertake more investment early in their tenures to gain benefits at a later stage of their careers, but they also have a strong need to demonstrate their competence at the outset of their appointments by addressing social environmental issues, thereby reducing the need to do so later in their tenures (Chen et al. 2019).

Prior literature on CEO tenure as a legitimisation of power reports mixed evidence on how CEO tenure is related to CSR. For example, Huang (2013) establishes a positive association between CEO tenure and CSR performance, while Chen et al. (2019) and Lewis et al. (2014) show a negative association, and Oh et al. (2018) derive insignificant results. Newly appointed CEOs are more objective about how their companies should run and are more willing to experiment and pursue new initiatives by which they can gain the benefits of such projects at a later stage of their tenure (Chen et al. 2019). The foregoing arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

H3

CEO legitimate power is negatively associated with environmental performance.

3 Research methods

3.1 Data and sample

The study is based on a sample of companies listed on the London Stock Exchange (FTSE-All-Share) over a nine-year period, 2011–2019. The chosen period enables us to test the impact of the CEO on environmental practices during the last decade. The UK institutional context provides a valuable opportunity to investigate the role of CEOs in enhancing environmental performance and creating long-term sustainable value. Regulations related to environmental issues in the UK were instituted in 1990, when the Environmental Protection Act 1990 was implemented, which focused on mitigating and remediating environmental degradation through improved waste management and the control of carbon emissions into the atmosphere. Moreover, the UK is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), being a signatory to the Paris Agreement. It is also the first country to require listed companies to include carbon emissions data in their annual reports under the Companies Act (2006) (Haque and Ntim 2018). Data are collected from two databases: CEO characteristics and board variables from the BoardEx database; and ESG data, comprising ESG scores, financial variables, and industrial affiliations, from the Eikon database. We winsorize all variables at the 1% and 99% percentiles to remove the effect of outliers. Our final sample for the empirical analysis comprises 1540 firm-year observations for the analyses.

3.2 Variables definitions and measurement

3.2.1 The dependent variable: environmental performance

We employ three environmental performance measures. First, we use the environmental pillar scores to measure environmental performance (Duque-Grisales and Aguilera-Caracuel 2021; Yarram and Adapa 2021).Footnote 4 Second, we use the emission score, which measures a firm’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions. Emission scores are designed to measure companies’ relative emission performance standards and assess companies’ commitment to reducing carbon emissions. Third, we construct a composite environment index, which recognises several practices (i.e., carbon emission target, carbon credit, environmental fines, and ISO certification). The index examines the following situations:

-

i.

Target emission is an indicator variable that takes a value of 1 if a firm sets a target for emission reduction, and 0 otherwise. The UK government has implemented several environmental policies for companies to comply with emission reduction targets and improve environmental performance (Haque and Ntim, 2018). Following Luo and Tang (2014), we consider carbon targets to be one of the key indicators of environmental performance, as companies with emission reduction targets are expected to undertake better environmental practices to achieve those targets.

-

ii.

ISO 14000 certification is a framework for the recognition of improved environmental impact management. We create an indicator variable which takes a value of 1 if a firm achieves ISO 14000 certification, and 0 otherwise. Prior research addresses the importance of ISO 14001 certification in encouraging better environmental practices (Meng et al. 2014; Arimura et al. 2016; Boiral et al. 2018; Erauskin-Tolosa et al. 2020). Li et al. (2020) report that ISO 14001 certification can be considered as a key element for corporate environmental engagement and performance. Therefore, firms with ISO 14001 certification have developed better green management and responsible behaviour.

-

iii.

Environmental fines, which is an indicator variable taking a value of 1 if a firm reports environmental fines during the fiscal year, and 0 otherwise, is multiplied by − 1 to capture good behaviour. Governments can ensure compliance with environmental policies by applying financial fines for the violation of environmental regulations (Habib and Bhuiyan 2017). Environmental penalties reflect the legal dimension of environmental engagement. Companies that do not meet the minimum requirements imposed by law for environmental practices are subject to environmental fines (Li et al. 2020). Shevchenko (2021) reports that regulatory pressures in the form of financial fines for environmental violations lead to improvements in corporate environmental performance. Therefore, we include environmental fines as an indicator for environmental practices, considering that firms that do not have environmental fines have less environmental violations and are likely to have better environmental performance.

-

iv.

Carbon credit is an indicator variable taking a value of 1 if a firm purchased or produced carbon credits and allowances during the fiscal year, and 0 otherwise. Based on the carbon trading scheme, a limited number of tradable emissions allowances are created to be distributed among participants in an economy. Companies that emit more than the allocated allowances are subject to fines; alternatively, they can buy emissions allowances from other companies that underuse their allowances (Zakeri et al. 2015). We follow Hartmann and Vachon (2018) by including carbon credit as an indicator of environmental performance. The carbon credit scheme creates pressures by the imposition of fines in the event of excessive emissions of pollution, providing incentives by enabling companies controlling their emissions to sell surplus allowances, thus encouraging better environmental practices (Zakeri et al. 2015). The composite index is the sum of the four indicators described above, (i.e., target emission, ISO 14000 certificate, environmental fines, and carbon credit) generated by a firm in a specific year.

3.2.2 The independent variables: CSR-linked compensation and CEO power

Our main independent variables are CEO incentives linked to CSR targets and CEO power, represented by CEO managerial power and CEO legitimate power. Prior literature argues that the implementation of non-financial items, including CSR-related items, in CEO contracts help increase environmental and social goals in line with stakeholder interests (Velte 2020) and have a positive impact on environmental performance (Cordeiro and Sarkis 2008; Haque 2017). The connection between CEO compensation and CER incentivises CEOs to engage in socially responsible investment. CSR-linked compensation is an indicator variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm discloses CSR-linked incentives in its remuneration report, and 0 otherwise. Data are collected from the Eikon database.

A CEO’s managerial control of a board is measured using two different proxies. First, CEO duality, which is an indicator of the formal authority that CEOs have over a board (Walls and Berrone 2017). The CEO will have greater power when s/he acts as the CEO and chairman at the same time. The duality role is likely to improve the decision-making process at the top management level, which could affect corporate performance (Elsayih et al. 2020). Second, the proportion of executive directors on a board reflects the power and influence that CEOs have over investment decisions (Walls and Berrone 2017; Garcia-Sanchez et al. 2020). We combine these two dimensions to create CEO power scores for each of the two dimensions using a dichotomous procedure, in which we (i) assign a value of 1 if the CEO is also the chair of the board, and 0 otherwise; and (ii) assign a value of 1 if the percentage of executive directors on the board is above the median, and 0 otherwise. The composite index is the sum of the individual scores attainable by the firm for a specific year.

Further, CEO legitimate power is measured by CEO tenure (Walls and Berrone 2017). CEO tenure has significant implications for firm operations (Chen et al. 2019), as its length can be a useful measure of his/her knowledge of the organisation and engagement with stakeholders (Elsayih et al. 2020). CEOs have strong incentives to signal their good performance at an early stage of their tenure, so they can reap the benefits of their positive achievements in the future. These incentives are likely to be represented by long-term projects due to make positive returns in the long-term (Pan et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2019). CEO tenure represents the number of years that an incumbent has been the CEO.

3.2.3 Control variables

We include control variables to account for board, and firm-specific factors that might affect firms’ environmental performance, in line with prior literature (Huang, 2013; Lewis et al. 2014; Ji 2015; Chen et al. 2019; Elsayih et al. 2020). We control for a CSR committee because firms that have one are compelled to promote social and environmental initiatives (Al-Shaer and Zaman 2016; Birindelli et al. 2019). SUSCOM is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 If a board-level sustainability committee exists, and 0 otherwise. We also include CEO age in the number of years (Lewis et al. 2014). Prior literature argues that larger boards are more diverse and include directors with different backgrounds and levels of expertise, which could lead to greater commitment to CSR activities (Ben-Amar et al. 2017; Zaid et al. 2020). Board size is measured as the number of directors on a board. A higher proportion of independent directors on a board helps to increase monitoring and facilitate greater emphasis on CSR (Al-Shaer and Zaman 2016). We thus include board independence measured as the proportion of independent directors on a board. Prior literature argues that female directors are more likely to be stakeholder-oriented and engage in socially responsible activities (Al-Shaer and Zaman 2016; Glass et al. 2016; Ben-Amar et al. 2017). Board gender diversity is measured using the proportion of women on the board.

Finally, we control for firm-specific variables. These are firm size, measured by the natural logarithm of total assets; foreign sales, measured by the percentage of international sales of total sales; return on assets, measured by net income before extraordinary items divided by total assets; TOBINSQ, calculated by dividing the sum of firm equity value, the book value of long-term debt and current liabilities by total assets; firm loss, using an indicator variable that equals one when the current year's net income is negative and zero otherwise; leverage measured by the ratio of total liabilities scaled by total assets, and industry and year dummies.

3.3 Econometric model

To examine the impact of CEO power and compensation on environmental performance, we employ the multivariate regression model below using OLS as the baseline approach. The estimation model is specified as:

where \(EN{V}_{performance}\) represents a firm’s environmental performance measured by the three alternative measures discussed in Sect. 3.2.1. All regressions include year and industry fixed effects, and industry dummies are created based on the SIC one-digit industry classification. Detailed variable definitions are provided in Table 1.

3.4 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of environmental performance variables, CEO variables and control variables for all companies in the sample. We find the mean value of the environmental score to be 39.35 and the mean value of emission score 48.11. Both scores are collected from the Thomson Reuters Asset4 database and calculated using a percentile rank scoring relating to the environmental and emission reduction themes.Footnote 5 We also find that 43% of the companies in the sample are ISO 14000 certified, 43% of the companies set emission targets, 0.05% of companies reported environmental fines during the fiscal year, and 0.04% of the companies purchased or produced carbon credits. Finally, the composite environmental performance index ranges from 0 to 4, with an average mean value of 1.22.

Regarding CEO managerial power, we find that 11% of the companies have CEOs with dual roles, i.e., chief executive officer and board chair; while approximately half of the companies have boards with a proportion of executive directors above 42%. Descriptive statistics demonstrate that 32% of the companies disclose the inclusion of CSR-related targets in their CEO compensation contracts, which is lower than the value of 49.3% reported in Al-Shaer and Zaman (2019) for a sample of FTSE350 companies.Footnote 6 The average of a CEO’s tenure is 5.45 years, which is lower than the average CEO tenure of 8.378 reported in Chen et al. (2019) for a sample of US firms; while the average CEO age is 52, which is less than the average value of 64 reported in Chen et al. (2019). Regarding board variables, we find that 64% of the companies’ boards in the sample incorporate CSR committees; have a mean board size of 8.65; independent directors accounting for 57% of board members; and that 19% of directors are female. Finally, with respect to firm-specific variables, we find mean firm size to be 21.19, measured using the natural log of total assets; that 42% of the companies’ revenues come from foreign sales; that the mean ROA is 0.06; that the mean TOBINSQ is 0.87; the mean leverage 0.48; and that, on average, 14% of the firms sampled have reported losses during the period of the study.

Table 3 reports the correlation matrix for variables used in the analysis. The Pearson correlation coefficients do not display evidence of significant multicollinearity issues. We include one proxy for environmental performance, viz. ENV_score.Footnote 7 We find that environmental performance has a significant and positive correlation with CSR-linked compensation and CEO age and has a significant and negative correlation with CEO tenure. Furthermore, environmental performance has significant and positive correlations with SUSCOM, BODSIZE, BODIND, and BODDIV. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values range from 2.05 to 2.70, with a mean value of 2.40.

4 Empirical results and discussions

4.1 Baseline regression results

4.1.1 Multivariate analysis

Table 4 presents the results of the impact of CEO variables on environmental performance, measured by ENV_score. We include CSR-linked compensation and control variables in Model 4.1, CEO_managerial power and control variables in Model 4.2, CEO_legitimate power and control variables in Model 4.3, and finally we include the three independent variables in Model 4.4 and control variables. The results show that CSR-linked compensation is positive and significant at a 1% level in Models 4.1 and 4.4, suggesting that the inclusion of CSR-related items in CEO contracts incentivises CEOs to pursue social and environmental targets in line with stakeholders’ interests (Velte, 2020). This result extends the findings of Al-Shaer and Zaman (2019), showing that the inclusion of CSR-related targets in CEO compensation contracts improves the external assurance of sustainability reports for UK companies during the period 2011–2015. Focusing on CER, we establish that CEO compensation linked to CSR improves environmental performance. The result supports stakeholder theory, demonstrating that CSR-linked compensation serves as a motivational tool compelling CEOs to adopt a sustainable approach and to engage in environmental practices that respond to stakeholders’ interests.

CEO_managerial power is negative and significant at a 5% level in Model 4.2 and at a 10% level in Model 4.4, indicating that powerful CEOs who hold dual roles, and have a larger proportion of executive directors on their boards, are less likely to make environmental-related decisions, using their power instead to increase shareholders’ returns and avoid the costs associated with long-term projects. This finding is consistent with Rashid et al. (2020), indicating that CEO power is negatively associated with the level of CSR disclosure; and also aligning with research undertaken by Garcia-Sanchez et al. (2020), showing that CEOs with greater power prevent disclosure of integrated information. We extend these studies by examining the role of CEO managerial power on environmental performance in a unique context. This finding supports managerial power theory, highlighting the significant role of powerful CEOs within the top management team. Such individuals can influence companies’ decisions by engaging less in environmental projects to avoid any potentially excessive development costs (Park et al. 2018; Rashid et al. 2020). CEO power can be considered in this context as giving an opportunity to CEOs to exercise their discretion and to engage in self-serving behaviour that conflicts with stakeholders’ interests (Bebchuk and Fried, 2006).

We find CEO_legitimate power to be negative and significant at a 1% level in Models 4.3 and 4.4, indicating that newly appointed CEOs engage in environmental activities and respond to environmental issues. CEOs may use engagement in environmental initiatives as a signal to mitigate career concerns in the early years of their tenure (Chen et al. 2019). Newly appointed CEOs are open-minded about how an organisation should run and are more willing to experiment and pursue innovative strategies from which they can gain benefit at a later stage of their tenure (Lewis et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2019). Our finding is consistent with the study of Chen et al. (2019), showing that US firms’ CSR performance is significantly higher in CEOs’ early tenure than in their later tenure. We add to their work by investigating the impact of CEO tenure on environmental performance in the UK context, which is a less rigid and regulated environment. Our findings support the career concern hypothesis (Chen et al. 2019), as newly appointed CEOs are expected to conform to stakeholder demands by engaging in environmental initiatives that help them to demonstrate their competence at an early stage of their tenure, which leads to the establishment of a trusted relationship with stakeholders.

With regard to control variables, results show that CEO age is positive and significant at a 1% level, confirming that the older the CEO, the more likely s/he is to engage in projects that have a positive effect on environmental performance. Among other corporate governance variables, we find the presence of a sustainability committee (SUSCOM) to be positive and significant at a 1% level; BODSIZE to be positive and significant at 5%; BODIND to be positive and significant at 1%; and BODDIV to be positive and significant at 1%. These results indicate that the influence of CEOs within a firm is more pronounced when the board is larger, is more independent, and more diverse, confirming the effective role that corporate governance plays in improving environmental performance (Liao et al. 2018; Husted et al. 2019). Overall, our findings provide support for the study’s hypotheses and confirm the significant impact of CEO power and CSR-linked compensation on environmental performance.

In Tables 5 and 6, we re-run the regression tests using Emission_score and ENV_index respectively, as proxies for environmental performance. It is noteworthy that ENV_index is an ordinal variable with lower (0) and upper (4) bounds. Hence, the model specification should be non-linear, and we use the ordered probit regression in our tests (Al-Shaer et al. 2017; Cabeza‐García et al. 2018). The results are qualitatively similar to our baseline results reported in Table 4, showing that environmental performance is more pronounced in CEOs’ early tenure than in their later tenure. CEOs with greater managerial power may not emphasize environmental activities because of additional costs to their firms, and they tend to make trade-offs between shareholders and stakeholders’ returns. Moreover, the results show that CEO compensation linked to CSR has a positive impact on environmental performance. Designing and implementing a compensation policy linked to environmental engagement motivate CEOs more involved in such strategic activities.

4.1.2 Additional analysis- Stratified sampling based on board-specific characteristics

In Table 7, we divide the study’s sample into two subsamples based on board diversity. Extant literature suggests that CEO impact on environmental performance might be influenced by the diversity of the board. Female directors are more likely to be independent (Al-Shaer and Zaman, 2016) and monitor managers’ behaviour for any opportunistic activities than they might undertake (Srinidhi et al. 2011; Husted and de Sousa-Filho, 2019). They are more likely to be stakeholder-oriented and concerned about socially responsibility and environmental developments (Jain and Jamali 2016). We expect that a board with a higher proportion of female directors will impose pressures on CEOs to engage in environmental practices that drive the long-term value of the firm. Accordingly, we divide the sample into boards with a diversity of directors (i.e., female directors above the median) and boards with a higher proportion of male directors. The results, presented in Table 7, demonstrate that CEO_legitimate power has a significant, negative impact on environmental performance, indicating that newly appointed CEOs are willing to pursue new environmental initiatives that improve performance when there are more female directors on the board. Moreover, CSR-linked compensation is positive and significant, confirming that rewarding CEOs with incentives helps to motivate them to improve environmental performance regardless of the diversity of the board.

We further divide the sample based on board independence in Table 8. Corporate boards with a larger proportion of independent directors are likely to enhance monitoring and impose pressures on CEOs to undertake environmental initiatives (Chen et al. 2019). Hence, we group the firms into two subsamples comprising boards with more independent directors (if the board has independent directors above the median) and boards that are dominated by more executive directors. We find that when the board includes a lower proportion of independent directors, CEO_managerial power is negative and significant with environmental performance, indicating that if boards are less independent, CEOs enjoy more managerial power and are likely to use corporate resources to make short-term investment decisions that increase shareholders’ wealth because they face less resistance from the board. On the other hand, CEO_legitimate power is negative and significant with environmental performance when the board is more independent, establishing that newly appointed CEOs’ incentives to mitigate career concerns and communicate through environmental initiatives are stronger when there are more independent directors. This supports the career concern hypothesis that early tenure CEOs are likely to engage in environmental projects and signal their good behaviour to mitigate career concerns when faced with more independent boards. CSR-linked Compensation is positive and significant with environmental performance regardless of the proportion of independent directors on the board.

4.1.3 Additional analysis- stratified sampling for firm-specific characteristics

Next, we explore how the industrial sector influences the impact of CSR-linked CEO compensation and CEO power on environmental performance by testing both an environmentally sensitive industry subsample and a non-sensitive industry subsample. Companies that trade in consumer goods, basic materials, utilities, industrials, and the oil and gas industries are included in the environmentally sensitive industry subsample (Al-Shaer and Zaman, 2019); while companies operating in financial services, technology and telecommunications, consumer services and the health care industries are included in the non-environmentally sensitive industry subsample.Footnote 8 The results in Table 9 are consistent with the main findings for the environmentally sensitive subsample, confirming that the impact on CEO variables on environmental performance, i.e., CSR- linked compensation, CEO_managerial power and CEO_legitimate power, are more pronounced for firms operating in the environmentally sensitive sector.

In Table 10, we divide the sample into loss-making firms and non-loss-making firms. The result shows that CSR-linked compensation, managerial power, and legitimate power have no impact on environmental performance for the subsample of firms that are making losses during the period of the study. This confirms that CEOs who have managerial power over the top management team while holding dual roles are less likely to engage in costly environmental practices when their firms are enduring losses. Results also suggests that CEO tenure and CSR-linked incentives have no impact on environmental performance. Regarding the non-loss-making firms’ subsample, findings are qualitatively similar to the main findings reported in Table 4.

The importance of businesses’ engagement in environmental protection has increased among investors, regulatory bodies, and other stakeholders in recent years. To test whether there have been variations in the impact of CEO attributes in recent years as compared to earlier years of the sample period, we divide the sample into the older years’ subsample (2011–2014) and the recent years’ subsample (2015–2019). Table 11 tests the effect of CEO power and CSR-linked compensation on environmental performance in the recent years of the sample period in comparison to its earlier years. The result demonstrates that CSR-linked compensation is positive and significant for both periods, confirming that rewarding CEOs with incentives helps to motivate them to improve corporate environmental performance. Moreover, CEO_legitimate power has a significant and negative impact on environmental performance. Our results hold over both time periods and remain consistent with the main findings.

4.2 Addressing endogeneity

CEOs’ diverse sources of power could be endogenous and influenced by some omitted variables (Zaman et al. 2021). To address this concern, we use GMM and 2SLS regressions (with IVs) to isolate the effect of CEO variables on environmental performance from other sources of variation. This requires the selection of valid instruments correlated with CEO variables but uncorrelated with environmental performance. Board size and board independence are relatively stable over time and may be much less likely to be impacted by firm performance than other governance variables, which is widely recognised in corporate governance research (e.g., Armstrong et al. 2010; Brown et al. 2011; Al-Shaer et al. 2017; Nuber and Velte, 2021; Boutchkova et al. 2022). Therefore, we, follow prior research in our choice of instrumental variables (IVs) (Ben-Amar et al. 2017; Nuber and Velte, 2021), selecting the industry average of board size, BODSIZE and board independence, BODIND. This is because a higher industry’s average of BODSIZE yields a higher CEO power, and a higher industry’s average of BODIND reduces the level of CEO power i.e., when there is a larger proportion of executive directors on a board, CEOs become more powerful. Moreover, there is no direct relationship between the industry’s average of BODSIZE and BODIND and our dependent variable (environmental performance). Hence, the industry’s averages of BODSIZE and BODIND appear to be viable instruments in this context. To test their validity, we examine the correlation between the instruments and the error term, using the Sargan test of over-identification of restrictions and predicting an insignificant sargan. We test for the potential endogeneity of each explanatory variable, reporting the second stage regression results in Table 12. We also use the 2SLS estimator and report the second stage regression result inTable 13.Footnote 9 Overall, our findings are qualitatively similar to our main findings, providing support for our hypotheses predicting an association between CEO variables and environmental performance.

We address endogeneity using the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) approach. We compute the industry averages of our CEO variables, viz. CEO compensation linked to CSR, CEO managerial power, and CEO legitimate power, and create a dummy for each predictor based on the cut-off value of the industry average (Shahab et al. 2022). We run the first stage of the PSM approach by employing a probit model that uses CEO indicators as the dependent variable, and variables that determine CEO power and compensation as regressors (board and firm-specific variables), utilising the nearest neighbour matching technique with a 1% radius matching approach (Shipman et al. 2017). We then re-estimate our model for the matched sample and report the result in Table 14. Results for the matched sample remain the same after using the PSM technique. The results are consistent with our baseline results that that CEO compensation linked to CSR has a positive impact on environmental performance and CEO managerial and legitimate powers have a negative impact on environmental performance.

Finally, to minimise sample bias and correct sample-induced endogeneity, we adopt the Heckman (1979) two-step estimation approach. We first create dummy variables for CEO variables, viz. CEO compensation linked to CSR, CEO managerial power, and CEO legitimate power based on the cut-off value of the industry average. In the first stage, we run a probit model using CEO dummies as the dependent variables and board and firm-specific variables as controls. The estimated parameters are used to compute the Inverse Mills’ Ratio (IMR), which is then included as an additional explanatory variable in the second stage estimation (Green 1993). Table 15 reports the coefficient estimates from the second-stage regression. Results demonstrate that CSR- linked compensation is positive and significant with environmental performance, and both CEO_managerial power and CEO_legitimate power are negative and significant with environmental performance. The IMR is insignificant, establishing that sample selection bias is not present, and that OLS regression is appropriate (Al-Shaer and Zaman 2019). Overall findings are qualitatively similar to our main findings and indicate support for the study’s hypotheses on the association between CEO variables and environmental performance.

5 Conclusion

Our study, for the first time, examines the impact of CEO power and compensation for CSR on environmental performance. We investigate the role of CEO managerial power, proxied by CEO duality and the presence of executive directors on the board, and CEO legitimate power, proxied by CEO tenure. The study posits a significant effect of CEO incentives, CEO managerial power, and CEO legitimate power on environmental performance. We use multiple proxies for environmental performance, including environmental scores and emission scores, and create an index to assess the level of a firm’s engagement in environmental practices, comprising an emission target, the purchase or production of carbon credits, the reporting of environmental fines, and the receipt of ISO 14000 certification for better environmental impact management.

Using a sample from the FTSE-All-Share index for the period 2011–2019, we establish that CEO compensation linked to CSR is positively associated with environmental performance, whereas CEO managerial and legitimate powers are negatively associated with environmental performance. Our subsample analysis shows that when corporate boards are less independent, CEOs wield greater managerial power, and that having a longer tenure makes them more resistant to change and to engaging in environmental initiatives. Newly appointed CEO’s incentives to engage in environmental initiatives increase with more diverse boards. Moreover, CSR-related targets in CEO compensation contracts motivate CEOs to engage in environmental activities that improve environmental performance, regardless of the independence and diversity of the board. Finally, our findings hold for subsamples of firms operating in environmentally sensitive sectors and for a subsample of non-loss-making firm. We control for endogeneity by using the GMM and 2SLS estimators with (IVs) and the PSM and Heckman two-stage techniques, thus substantiating our results.

The study’s findings complement an existing and expanding literature on the CEO and environmental performance relationship by establishing that firms’ effective implementation of environmental practices depends to a significant extent on proactive leadership. CEO incentives aligned to CSR can increase engagement in environmental activities and ensure that ecological issues are adequately considered within the firm. Companies need to consider CSR-related targets in CEO compensation contracts to motivate CEOs to achieve those targets. Finally, this study highlights the importance of having more diverse and independent boards that will encourage CEOs to engage in corporate greening and pursue sustainable strategies that achieve stakeholder-oriented outcomes.

Focusing on CSR- linked CEO compensation and power, our study signposts fruitful avenues for further research. For example, it would be valuable to examine other CEO characteristics, such as industry expertise, skills, culture, and religion, and how they might stimulate firms to adopt green strategies. Moreover, future research could examine CEO personal traits or values that are difficult to measure directly by accessing primary sources of qualitative data, including interviews and questionnaires. Other proxies of CEO power could also be used (e.g., CEO Pay Slice, CEO ownership) to explain the process by which CEOs exercise their power to engage in environmental projects that impact ecological performance. Finally, it could be instructive to examine the role of CEOs in different institutional settings and make comparisons between firms operating in different institutional contexts.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Notes

Please visit: The Role of CEO in Addressing Climate Change | The CEO Views.

Environmental, Social and Governance.

What comes first—profit or responsibility?—KPMG United Kingdom (home.kpmg).

The database provides a comprehensive assessment of a firm’s ESG performance based on the information disclosed on the environmental, social and governance factors. ESG scores are calculated by Thomson Reuters using a percentile rank scoring relating to the environment, social, and governance dimensions (Thompson Reuters Eikon Database).

Thomson Reuters ESG scores are designed to measure a company’s relative ESG performance, commitment, and effectiveness transparently and objectively across different themes including the environment and emission based on company-reported data.

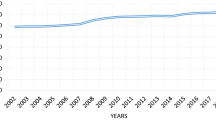

Overall, we find an increasing trend of the inclusion of CSR incentives in remuneration reports in the recent years (2017-2019) (please see Appendix 2).

We conduct similar correlations with other environmental performance proxies included in this study (untabulated).

We have 992 companies (64.42%) belong to the non-environmentally sensitive industries and 584 companies (35.58%) belong to the environmentally sensitive industries.

In the first stage, we regress CEO variables against the industry’s average of BODSIZE and BODIND and firm-specific variables. Results from the first-stage regression show that the industry’s average of BODSIZE and firm size have positive and significant associations with CEO variables and the industry’s average of BODIND has a negative and significant association with CEO variables. The untabulated first-stage regression results can be provided upon request.

References

Al-Shaer H, Zaman M (2016) Board gender diversity and sustainability reporting quality. J Contemp Account Econ 12(3):210–222

Al-Shaer H, Zaman M (2019) CEO compensation and sustainability reporting assurance: evidence from the UK. J Bus Ethics 158(1):233–252

Al-Shaer H, Salama A, Toms S (2017) Audit committees and financial reporting quality: evidence from UK environmental accounting disclosures. J Appl Acc Res 18(1):2–21

Arimura TH, Darnall N, Ganguli R, Katayama H (2016) The effect of ISO 14001 on environmental performance: resolving equivocal findings. J Environ Manage 166(1):556–566

Armstrong CS, Guay WR, Weber JP (2010) The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. J Account Econ 50:179–234

Baraibar-Diez E, Odriozola MD, Fernandez Sanchez JL (2019) Sustainable compensation policies and its effect on environmental, social, and governance scores. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26(6):1457–1472

Bebchuk LA, Fried JM (2006) Pay without performance: overview of the issues. Acad Manag Perspect 20(1):5–24

Ben-Amar W, Chang M, McIlkenny P (2017) Board gender diversity and corporate response to sustainability initiatives: evidence from the carbon disclosure project. J Bus Ethics 142(2):369–383

Berger PG, Ofek E, Yermack DL (1997) Managerial entrenchment and capital structure decisions. J Financ 52(4):1411–1438

Berrone P, Gomez-Mejia LR (2009) Environmental performance and executive compensation: an integrated agency-institutional perspective. Acad Manag J 52(1):103–126

Birindelli G, Iannuzzi AP, Savioli M (2019) The impact of women leaders on environmental performance: evidence on gender diversity in banks. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26(6):1485–1499

Boiral O, Guillaumie L, Heras-Saizarbitoria I, TayoTene CV (2018) Adoption and outcomes of ISO 14001: a systematic review. Int J Manag Rev 20(2):411–432

Boutchkova M, Cueto D, Gonzalez A (2022) Test power properties of within-firm estimators of ownership and board-related explanatory variables with low time variation. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01074-8

Brown P, Beekes W, Verhoeven P (2011) Corporate governance, accounting and finance: a review. Accounting and Finance 51:96–172

Cabeza-García L, Fernández-Gago R, Nieto M (2018) Do board gender diversity and director typology impact CSR reporting? Eur Manag Rev 15(4):559–575

Cai Y, Jo H, Pan C (2011) Vice or virtue? The impact of corporate social responsibility on executive compensation. J Bus Ethics 104(2):159–173

Callan SJ, Thomas JM (2011) Executive compensation, corporate social responsibility, and corporate financial performance: a multi-equation framework. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 18(6):332–351

Callan SJ, Thomas JM (2014) Relating CEO compensation to social performance and financial performance: does the measure of compensation matter? Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 21(4):202–227

Chen WT, Zhou GS, Zhu XK (2019) CEO tenure and corporate social responsibility performance. J Bus Res 95:292–302

Cordeiro JJ, Sarkis J (2008) Does explicit contracting effectively link CEO compensation to environmental performance? Bus Strateg Environ 17(5):304–317

Davis JH, Schoorman FD, Donaldson L (1997) Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review 22(1):20–47

Deckop JR, Merriman KK, Gupta S (2006) The effects of CEO pay structure on corporate social performance. J Manag 32(3):329–342

Devers CE, Cannella AA Jr, Reilly GP, Yoder ME (2007) Executive compensation: a multidisciplinary review of recent developments. J Manag 33(6):1016–1072

Duque-Grisales E, Aguilera-Caracuel J (2021) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. J Bus Ethics 168(2):315–334

Elsayih J, Datt R, Hamid A (2020) CEO characteristics: do they matter for carbon performance? An empirical investigation of Australian firms. Social Responsibility Journal 17(8):1279–1298

Erauskin-Tolosa A, Zubeltzu-Jaka E, Heras-Saizarbitoria I, Boiral O (2020) ISO 14001, EMAS and environmental performance: a meta-analysis. Bus Strateg Environ 29(3):1145–1159

Fabrizi M, Mallin C, Michelon G (2014) The role of CEO’s personal incentives in driving corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 124(2):311–326

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Separation of ownership and control. J Law Economics 26(2):301–325

Francoeur C, Melis A, Gaia S, Aresu S (2017) Green or greed? An alternative look at CEO compensation and corporate environmental commitment. J Bus Ethics 140(3):439–453

Freeman RE (1984) Strategic management: a stakeholder perspective. Pitman Publishing, Boston

Garcia-Sanchez IM, Raimo N, Vitolla F (2020) CEO power and integrated reporting. Meditari Account Res 29(4):908–942

Glass C, Cook A, Ingersoll AR (2016) Do women leaders promote sustainability? Analyzing the effect of corporate governance composition on environmental performance. Bus Strateg Environ 25(7):495–511

Greene W (1993) Econometric analysis, 5th edn. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Groysberg B, Lee J, Price J, Cheng J (2018) The leader’s guide to corporate culture. Harv Bus Rev 96(1):44–52

Habib A, Bhuiyan MBU (2017) Determinants of monetary penalties for environmental violations. Bus Strateg Environ 26(6):754–775

Haque F (2017) The effects of board characteristics and sustainable compensation policy on carbon performance of UK firms. Br Account Rev 49(3):347–364

Haque F, Ntim CG (2018) Environmental policy, sustainable development, governance mechanisms and environmental performance. Bus Strateg Environ 27(3):415–435

Hartmann J, Vachon S (2018) Linking environmental management to environmental performance: the interactive role of industry context. Bus Strateg Environ 27(3):359–374

Heckman J (1979) Sample selection as a specification error. Econometrica 47:153–161

Hong B, Li Z, Minor D (2016) Corporate governance and executive compensation for corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 136(1):199–213

Huang SK (2013) The impact of CEO characteristics on corporate sustainable development. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 20(4):234–244

Husted BW, de Sousa-Filho JM (2019) Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J Bus Res 102:220–227

Ibrahim S, Li H, Yan Y, Zhao J (2021) Pay me a single figure! assessing the impact of single figure regulation on CEO pay. Int Rev Financ Anal 73:101647

Jain T, Jamali D (2016) Looking inside the black box: the effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Corp Gov Int Rev 24(3):253–273

Ji YY (2015) Top management team pay structure and corporate social performance. J Gen Manag 40(3):3–20

Jizi MI, Salama A, Dixon R, Stratling R (2014) Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from the US banking sector. J Bus Ethics 125(4):601–615

Karim K, Lee E, Suh S (2018) Corporate social responsibility and CEO compensation structure. Adv Account 40:27–41

Kolk A, Perego P (2014) Sustainable bonuses: sign of corporate responsibility or window dressing? J Bus Ethics 119(1):1–15

Lewis BW, Walls JL, Dowell GW (2014) Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strateg Manag J 35(5):712–722

Li F, Li T, Minor D (2016) CEO power, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: A test of agency theory. Int J Managerial Finance 12(5):611–628

Li Y, Gong M, Zhang XY, Koh L (2018) The impact of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on firm value: the role of CEO power. Br Account Rev 50(1):60–75

Li Z, Liao G, Albitar K (2020) Does corporate environmental responsibility engagement affect firm value? The mediating role of corporate innovation. Bus Strateg Environ 29(3):1045–1055

Liao L, Lin TP, Zhang Y (2018) Corporate board and corporate social responsibility assurance: evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 150(1):211–225

Liu J, Zhang D, Cai J, Davenport J (2021) Legal system, national governance, and renewable energy investment: evidence from around the world. Br J Manag 32(3):579–610

Lu J, Liang M, Zhang C, Rong D, Guan H, Mazeikaite K, Streimikis J (2021) Assessment of corporate social responsibility by addressing sustainable development goals. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 28(2):686–703

Luo L, Tang Q (2014) Does voluntary carbon disclosure reflect underlying carbon performance? J Contemp Account Econ 10(3):191–205

Maas K, Rosendaal S (2016) Sustainability targets in executive remuneration: targets, time frame, country and sector specification. Bus Strateg Environ 25(6):390–401

Mallin CA, Michelon G (2011) Board reputation attributes and corporate social performance: an empirical investigation of the US best corporate citizens. Account Bus Res 41(2):119–144

Meng XH, Zeng SX, Shi JJ, Qi GY, Zhang ZB (2014) The relationship between corporate environmental performance and environmental disclosure: an empirical study in China. J Environ Manage 145:357–367

Muttakin MB, Khan A, Mihret DG (2018) The effect of board capital and CEO power on corporate social responsibility disclosures. J Bus Ethics 150(1):41–56

Nuber C, Velte P (2021) Board gender diversity and carbon emissions: European evidence on curvilinear relationships and critical mass. Bus Strateg Environ 30(4):1958–1992

Oh WY, Chang YK, Jung R (2018) Experience-based human capital or fixed paradigm problem? CEO tenure, contextual influences, and corporate social (ir) responsibility. J Bus Res 90:325–333

Pan Y, Wang TY, Weisbach MS (2016) CEO investment cycles. The Review of Financial Studies 29(11):2955–2999

Park JH, Kim C, Chang YK, Lee DH, Sung YD (2018) CEO hubris and firm performance: exploring the moderating roles of CEO power and board vigilance. J Bus Ethics 147(4):919–933

Rashid A, Shams S, Bose S, Khan H (2020) CEO power and corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure: does stakeholder influence matter? Manag Audit J 35(9):1279–1312

Rekker SA, Benson KL, Faff RW (2014) Corporate social responsibility and CEO compensation revisited: do disaggregation, market stress, gender matter? J Econ Bus 72:84–103

Schulze WS, Lubatkin MH, Dino RN, Buchholtz AK (2001) Agency relationships in family firms: theory and evidence. Organ Sci 12(2):99–116

Shahab Y, Gull AA, Rind AA, Sarang AAA, Ahsan T (2022) Do corporate governance mechanisms curb the anti-environmental behavior of firms worldwide? An illustration through waste management. J Environ Manage 310:114707

Sheikh S (2019) An examination of the dimensions of CEO power and corporate social responsibility. Rev Acc Financ 18(2):221–244

Shevchenko A (2021) Do financial penalties for environmental violations facilitate improvements in corporate environmental performance? An empirical investigation. Bus Strateg Environ 30(4):1723–1734

Shipman J, Swanquist Q, Whited R (2017) Propensity score matching in accounting research. Account Rev 92(1):213–244

Shui X, Zhang M, Smart P, Ye F (2022) Sustainable corporate governance for environmental innovation: a configurational analysis on board capital, CEO power and ownership structure. J Bus Res 149:786–794

Srinidhi B, Gul FA, Tsui J (2011) Female directors and earnings quality. Contemp Account Res 28(5):1610–1644

Tan M, Liu B (2016) CEO’s managerial power, board committee memberships and idiosyncratic volatility. Int Rev Financ Anal 48:21–30

Velte P (2020) Do CEO incentives and characteristics influence corporate social responsibility (CSR) and vice versa? A literature review. Social Responsib J 16(8):1293–1323

Walls J, Berrone P (2015) The power of one: how CEO power affects corporate environmental sustainability. Academy of Management Proceedings, Academy of Management. p 12338

Walls JL, Berrone P (2017) The power of one to make a difference: how informal and formal CEO power affect environmental sustainability. J Bus Ethics 145(2):293–308

Yarram SR, Adapa S (2021) Board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility: is there a case for critical mass? J Clean Prod 278:123319

Zaid MA, Wang M, Adib M, Sahyouni A, Abuhijleh ST (2020) Boardroom nationality and gender diversity: implications for corporate sustainability performance. J Clean Prod 251:119652

Zakeri A, Dehghanian F, Fahimnia B, Sarkis J (2015) Carbon pricing versus emissions trading: a supply chain planning perspective. Int J Prod Econ 164:197–205

Zaman R, Atawnah N, Baghdadi GA, Liu J (2021) Fiduciary duty or loyalty? Evidence from co-opted boards and corporate misconduct. J Corp Finan 70:102066

Zhang D, Zhang Z, Qiang J, Lucey B, Liu J (2021) Board characteristics, external governance and the use of renewable energy: international evidence. J Int Finan Markets Inst Money 72:101317

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Examples from remuneration reports containing CSR-linked pay

"The annual bonus is determined in line with performance relative to annual targets for safety, environmental, operational and financial measures. Performance shares vest in line with performance relative to three-year targets for rTSR, ROACE and a set of low carbon/energy transition measures." BP Annual Report, 2019.

"Remuneration linked to achievement of sustainability and climate change targets is a key part of our governance. For management employees—up to and including the ULE—incentives include fixed pay, a bonus as a percentage of fixed pay and a long-term management co-investment plan (MCIP) linked to financial and sustainability performance. The Sustainability Progress Index accounts for 25% of the total MCIP award and includes consideration of progress against our manufacturing scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas and sustainable palm oil targets, which among others, underpin our climate strategy." Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019.

"For a number of years we have supported the use of environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics by including them in the ‘Purpose and People’ component of the strategic measures. This year we are increasing our focus on sustainability metrics, in support of our commitment to the UN’s sustainable development goals and the Paris climate agreement. Both the 2020 annual incentive scorecard and the 2020–22 LTIP will include metrics that embed sustainable and responsible practices into our business operations in relation to climate, infrastructure, environment and community engagement" Standard Chartered Annual Report, 2019.

"The Committee considered the performance against the ESG metrics within the people and purpose element of the annual incentive scorecard and 2017–19 LTIP strategic measures, as well as the Group’s wider progress on ESG metrics (further details on pages 43 to 56), and determined that the outcomes were appropriate and that the incentive structures do not raise ESG risks by motivating irresponsible behaviour." Standard Chartered Annual Report, 2019.

"The Committee always seeks to ensure that the remuneration of our Executive Directors reflects the underlying performance of the business. When approving outcomes, we therefore considered the Group scorecard along with wider business and individual performance over 2019, including other achievements across the enterprise, such as advancing our Great Place to Work priorities and environmental, social and governance (ESG) goals. In that context, we believe that the payments outlined below fairly reflect performance" AstraZeneca Annual Report 2019.

"For annual bonus, the fairness of the formulaic Group scorecard outcome is considered in the context of overall business performance and the experience of shareholders. Such considerations include TSR performance and each Executive Director’s personal impact on the delivery of the strategy, ESG performance and other organisational achievements, such as inclusion and diversity targets and the realisation of technology based milestones. Each year there are important individual deliverables beyond the scorecard metrics which are taken into account when determining individual bonuses" AstraZeneca Annual Report 2019.

Appendix 2: CSR-linked compensation average by year

Year | CSR- linked Compensation |

|---|---|

2011 | 0.131 |

2012 | 0.312 |

2013 | 0.351 |

2014 | 0.419 |

2015 | 0.228 |

2016 | 0.211 |

2017 | 0.367 |

2018 | 0.398 |

2019 | 0.551 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Shaer, H., Albitar, K. & Liu, J. CEO power and CSR-linked compensation for corporate environmental responsibility: UK evidence. Rev Quant Finan Acc 60, 1025–1063 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01118-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01118-z