Abstract

Using the modified maximum daily return measure (LHR) defined as the difference between upward limit-hitting rates and downward limit-hitting rates, our paper documents the higher LHR, the lower subsequent returns, i.e., the so-called modified MAX effect, in the Taiwan stock market. Since Taiwan stock market requires listed companies to report their revenues every month, we further investigate how the arrival of revenue news affects these lottery-like stocks. It is found that when the high LHR is associated with positive shocks from the monthly revenue announcement, the stock becomes significantly less appealing to individual investors. As individual investors’ order imbalances drop substantially after the revenue announcement period, the modified MAX effect is diminished. We also find monthly revenues announcements greatly dilute the importance of quarterly earnings announcements and, therefore, play the more important role in determining the modified MAX effect. Overall, our study suggests that more frequent and promptly financial information disclosures, such as monthly revenue reports, are critical to improving market efficiency and reducing behavioral bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

Code availability

The code for data cleaning and analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

Notes

Several studies have identified evidence of the MAX effect in developed markets such as Europe, Australia, and Canada (e.g., Annaert et al. 2013; Walkshäusl 2014; Zhong and Gray 2016) as well as emerging markets such as Taiwan, mainland China, and India (e.g., Hung and Yang 2018; Nartea et al. 2017). A few researchers have conducted cross-national research; for instance, Cheon and Lee (2018a) found that of 42 countries, 26 have the MAX effect and that when a country has a higher level of individualism, the profitability of trading strategy based on the MAX effect is greater. Umutlu and Bengitöz (2017) found that the MAX effect prevails in the market index and industrial index.

Other stock exchanges only disclose financial statements once each quarter, and the quarterly revenues are revealed simultaneously with quarterly earnings. Hence, the related literature mainly discusses the role of quarterly revenue in quarterly earnings announcements (e.g., Chen et al. 2014; Jegadeesh and Livnat 2006). The results thereof show that revealing revenue and earnings in quarterly announcements simultaneously enables investors to have a more holistic evaluation of earnings information on account of revenue. Moreover, past revenue surprises can predict future earnings changes, indicating that revenue is a reference indicator for measuring the continuity of earnings growth (Jegadeesh and Livnat 2006).

According to TWSE data, the fraction of individual trading was approximately 90.73% in 1997. By 2018, the fraction of individual trading was 59.3%. The TWSE opened to foreign institutions in 2001; since then, the fraction of foreign investment has grown each year.

More specifically, MRA is defined as the difference between the days hitting upper limits and the days reaching lower limits during a five-day window surrounding the revenue announcement and then divided by the total trading days in a month. We define an LHR as a revenue-information-driven LHR, denoted by RA_LHR, when the following two conditions are met simultaneously: (1) MRA is at least as high as LHR; (2) \(MAX\left(1\right)\) occurs during the revenue announcement period. Other LHRs are unrelated to revenue information.

Specific measures comprise the implementation of the Information Disclosure and Evaluation System, active promotion of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) for the preparation of financial statements, and a reduction in the time window for announcing financial statements for a particular fiscal year. Corporate information transparency is critical for good corporate governance. In 2003, the TWSE began evaluating the information disclosure of listed companies and introduced public supervision to improve the efficiency of corporate governance. All publicly listed companies in Taiwan had to adopt the IFRS to enhance their accounting quality (Barth et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2010).

The YoY revenue change is used to compare the revenue for one period to the same period from the previous year, which indicates the revenue percentage change during the past twelve months. It can remove the seasonal effects of company business and help discern the long-term growth trends of revenues. As to the annual cumulative revenue, it represents revenue accumulated from the beginning of the year to the current month. When YoY revenue change is too volatile to distinguish the long-term trends, the YoY annual cumulative revenue change can be appropriate alternative indicator.

For example, the Economic Daily News is the leading brand with the largest newspaper circulation among Taiwan’s financial news media. One article from the Economic Daily News was posted on September 16, 2020 and the title was “seventeen stocks with highest-ever revenues are recommended during the pandemic”. It reported that “the strong profitability is the most important base of stock price momentum. Before quarterly earnings are reported, we can use their revenues from the previous month announced prior to the 10th of each month to identify the growth stocks that may be profitable in the future. To seize the short-term buying and selling signals, we can use the revenue as the main filter for stock selection with technical and chip analyses.” The related news report is on the following website: https://money.udn.com/money/story/12040/4860303

For example, Ku (2011) discussed the relationship between the profitability of the revenue momentum strategy and other momentum strategies in Taiwan market and shows significant earnings momentum and revenue momentum effects. Although the revenue momentum effect has a close relationship with the earnings momentum effect, neither effect is inclusive of the other.

Bali et al. (2011) suggested that MAX represents the right skewness of stock return distribution. Consequently, MAX should be persistent over time. When a stock has a high MAX in the previous month, it is more likely to have another high MAX in the future, which partly explains why investors are willing to overpay for stocks with a high MAX and why the MAX premium is produced. Nguyen and Truong (2018) argued that the persistence of the MAX is reduced if the high MAX is driven by earnings announcements.

For example, a specific stock has 4 days hitting upper limits and 1 day reaching lower limit in a month. Thus, the difference between the numbers of upper-limit hits and lower-limit hits is 3 (= 4 − 1). If the total trading days in this month is 20, the LHR of that stock is 0.15 (= 3/20), suggesting that the stock’s net sentiment in a month tends to be optimistic.

For example, one specific stock has 2 days hitting upper limits and zero day reaching lower limit during the revenue announcement period. Consequently, the difference between the numbers of upper-limit hits and lower-limit hits is 2 (= 2 − 0). If the total trading days in this month is 20, the MRA of that stock is 0.1 (= 2/20), indicating that the stock’s net sentiment generated from the revenue news in a month tends to be optimistic.

In the Nguyen and Truong’s (2018) study, the 10th‰ and median of LHR are both 0, whereas the 90th‰ is 7.692%. That is, the LHR has right-skewed distribution and many samples have zero LHR. We discuss the summary statistics of the MRA in the Sect. 4.1. As expected, the distribution of MRA is also positively skewed.

Notably, when analyzing quarterly earnings announcements, Nguyen and Truong (2018) encounter a similar issue. They suggest that if \(MAX\left(1\right)\) occurs during the earnings announcement periods, then it is mainly driven by the earnings information.

Because the LHR is employed to measure the net sentiment in a month, it is influenced by not only revenue announcements but also other events. To ensure that the LHR primarily reflects monthly revenue information instead of other events, we ensured that the net sentiment generated from the revenue news (MRA) is at least as high as the LHR.

For example, according to the summary statistics of SUS in Panel A of Table 1, the SUS mean value is 0.071, which is higher than its medium value (0.059) but less than its 70th‰ (0.331). Consequently, the stocks with SUS mean value would be separated into the medium group.

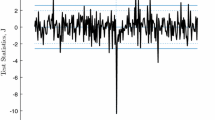

The average of each month’s regression coefficients is computed. The time-series averages divided by the time-series standard errors are t statistics, adjusted by a Newey–West method with 12 lags.

Specific measures comprise the implementation of the Information Disclosure and Evaluation System, active promotion of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) for the preparation of financial statements, and a reduction in the time window for announcing financial statements for a particular fiscal year. Corporate information transparency is critical for good corporate governance. In 2003, the TWSE began evaluating the information disclosure of listed companies and introduced public supervision to improve the efficiency of corporate governance. All publicly listed companies in Taiwan had to adopt the IFRS to enhance their accounting quality (Barth et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2010).

The literature shows that a traditional MAX effect exists in other markets with price limits, such as the Chinese market (e.g., Nartea et al. 2017) and the Korean market (e.g., Cheon and Lee 2018b). One possible explanation is that the Korean stock market has a higher price limit of 15%, which is more difficult to hit. The number of stocks whose MAX equals the upper bound imposed by the price limit is smaller, and thus the likelihood is lower that the MAX prevails across many stocks simultaneously. As a result, the significant MAX effect is still viable. Although the Chinese stock market has the same price limit as the Taiwanese stock market (10%), the behavioral biases and limits to arbitrage are stronger and further exacerbate the lottery anomaly (Yao et al. 2019).

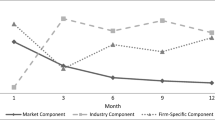

Two factors influence the time variation of the MAX premium. First, when market sentiment runs high, investors are prone to being overly optimistic and overestimate their chances of successful gambling, leading to increasing demand for lottery-like stocks and thus excessively pulling up the stock price (see Baker and Wurgler 2006; Fong and Toh 2014). Second, because investors have limited ability to process information and collecting information entails costs, to improve trading efficiency, they must allocate their attention to the area of interest. When a stock has a high MAX in down or uncertain markets, it may easily lead investors to devote excessive attention to it, thereby causing an overvalued stock price (Barber and Odean 2008; Gervais et al. 2001). Cheon and Lee (2018b) state that it is possible to identify one of the main influencing factors for the MAX effect by examining the relationship between market volatility and the MAX effect because market volatility is generally regarded as the inverse measure of market sentiment. In cases of high market volatility, market risk premiums increase and thus lower the stock price, usually leading to a downward trend in the market. Moreover, changes in stock trading reflect the fact that investors feel anxious and uneasy about future developments and are likely to trade more frequently. This scenario often occurs before a forthcoming recession. Cheon and Lee (2018b) observe that when the market volatility in the Korean stock market is large, the MAX effect is more significant, and thus, the attention-grabbing effect hypothesis is supported.

We use the lottery data released by Taiwan government from 2007 to 2018, obtained from Taiwan Lottery’s website (https://www.taiwanlottery.com.tw/index_new.aspx).

Only 15 attention-grabbing jackpots occur in our sample; thus, it is inappropriate to run the Fama and MacBeth (1973) regression owing to the insufficiency of data points. Instead, we run the pooled OLS regression of future stock returns on the LHR. The results are available upon request. The relationship between the LHR and stock return is generally negative, whereas the estimated coefficient of LHR \(\times\) JACKPOT is 12.458 (t = 8.35), where JACKPOT is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the month has the attention-grabbing jackpot and 0 otherwise. Namely, when the jackpot of Taiwan’s lottery increases, the gambling sentiment of the lottery reduces the preference for lottery-like stocks.

For stocks with a RA_LHR, the 10th‰, median value, and 90th‰ of the LHR is 0, 0, and 5%, respectively, and the corresponding values of the MRA are 0, 0, and 5% as well. Consequently, they indeed have similar distribution. However, for stocks in the NORA_LHR group, the LHR’s distribution is apparently different from the MRA. The 10th‰, median value, and 90th‰ of the LHR is − 4.545%, 0, and 10%, respectively, and the corresponding values of the MRA are 0, 0, and 4.545%.

We conduct several robustness checks for the results of Table 7. The results in Tables 15 and16 in the Appendix 3 indicate that our results hold for several alternative definitions of RA_LHR. First, we require RA_LHR to satisfy the condition that MRA be at least x times as large as the LHR, and we require MAX(1) to occur within a five-day window surrounding revenue announcements. Table 15 shows that when MRA is required to be at least 0.9 times as large as the LHR (i.e., x = 0.9), the modified MAX effect is still only existent in the NORA_LHR portfolio. Our results remain qualitatively unchanged when x is 0.8. Next, in addition to MRA being at least as large as the LHR, we define MAX(k) as the average of the k maximum daily return during the month, k = 2, 3, 4, 5, and we require $ MAX(k) to occur within a five-day window surrounding revenue announcements for RA_LHR. As shown in Table 16, when MAX(2) occurs during the announcement period, if the LHR is associated with revenue information, the modified MAX effect continues to be nonexistent; that is, for the RA_LHR portfolio, none of the alpha differences between high- and low-LHR portfolios is significantly negative. By contrast, in the NORA_LHR portfolio, the alphas of high − low LHR portfolios are significantly negative. In the case that k = 3, 4, or 5, the modified MAX effect still does not exist when the LHR is related to revenue information.

Standard cross-sectional regression places the same weight on a very large firm as on a small firm, but small firms only constitute a small ratio in the overall market capitalization, causing the use of equally weighted average regression model to provide a disproportionate result under the influence of small firms. To eliminate the aforementioned size effect, we take the market capitalization of stocks in the previous month as the weight to conduct the weighted least square regression as a robustness check of the relationship between the revenue announcement and the modified MAX effect. The results are reported in Table 17 in the Appendix 3. The estimated LHR coefficient is − 4.843 and statistically significant (t = − 4.04), suggesting that stocks with a higher LHR have lower future returns. As can be seen from Models 2 and 4, the modified MAX effect becomes more pronounced over time. Model 5 includes the interaction item (LHR × RA), whose regression coefficient is 3.425 (t = 1.94), and the regression coefficient on the LHR is − 5.044, indicating that when stocks have a higher LHR, which is related to revenue information, their subsequent returns are less likely to be lower.

We test whether the modified MAX effect exists in each of the three months after the portfolio formation. The results are reported in Table 18 in the Appendix 3 and suggest that high LHR stocks continue to provide lower returns in each of the three months after the portfolio formation. We also examine whether the modified MAX effect prevails in the presence of monthly revenue announcements in each of the three months after the portfolio formation. Table 19 in the Appendix 3 shows that when the LHR is mainly driven by revenue news, no significant (negative) relationship exists between the LHR and subsequent returns.

Lottery characteristic variables are defined as follows. The stock price (Price) is measured by the prior month’s stock closing price. Following Hung and Yang (2018), the daily return of the previous month is used to run the Fama–French three-factor alpha model, requiring that a stock be active for at least 10 trading days in a month. Subsequently, the second moment and third moment of the residuals are defined as the idiosyncratic volatility (IVOL) and idiosyncratic skewness (ISKEW), respectively.

We also adopt the joint-sorting method to develop portfolios and find the relationship among the lottery demand, monthly revenue announcements, and the modified MAX effect qualitatively unchanged. The results are available upon request.

Fong and Toh (2014) stated that when market sentiment is high, investors are overly optimistic about the future returns on stocks with a high MAX, causing these stocks to be even more overpriced. Kumar (2009) suggested that an unfavorable business climate may increase gambling. However, when the business climate improves, investors not only have higher risk tolerance and optimism toward the stock market but also are able to allocate more funds to lottery-like stocks (Kumar et al. 2016), resulting in a higher lottery demand.

There are two types of orders, namely, marketable limit order and nonmarketable limit order. For limit orders placed prior to the opening, a marketable limit order is a buy (sell) limit order whose price is greater (lower) than or equal to the corresponding closing price on the preceding trading day. For the orders submitted after the opening, a marketable limit order is a buy (sell) limit order whose price is greater (lower) than or equal to the prevailing best offer (bid) (see Lee et al. 2004).

Although the companies disclose the financial statements once each quarter, these announcements may occur in different months. In our sample, quarterly earnings announcements spread over all 12 months. Nguyen and Truong (2018) divided samples into earnings-unrelated MAX and earnings-related MAX every month and test whether the MAX effect prevails in each subsample. Therefore, we follow the method of Nguyen and Truong (2018) to investigate whether quarterly earnings reports affect the modified MAX effect in Taiwan. Taking the fact of earnings announcements mainly concentrated in several months into account, we further split the sample period into month with infrequent earnings announcements and month with frequent earnings announcements.

Alternatively, we define the month with frequent earnings announcements as the month whose rate is over 15% and run the regressions only using those months. The regression coefficients on interaction terms (LHR \(\times\) RA, LHR \(\times\) EA, LHR \(\times\) RA \(\times\) EA) are nonsignificant, indicating that our results are robust. The results are available upon request.

We measure the firm size by multiplying the previous month-end closing price by the number of outstanding shares. The book-to-market ratio is measured by dividing the book value of equity per share, as reported at the end of the most recent fiscal year, by the stock price.

The nine equally constructed benchmark portfolios might be strongly affected by share price, which is the only factor that is likely to change from month to month compared with the number of shares outstanding and book-to-market ratio. To address this problem, we conduct a robustness check of the information content of monthly revenue announcements. We measure the firm size by multiplying the previous year-end closing price by the number of outstanding shares. The results are reported in Table 20 in the Appendix 3. It is found that the average AR and CAR of the good news group are significantly higher than those of the bad news group and there is a significantly positive relationship between SUS and CAR. The results show the information content of monthly revenue announcements qualitatively unchanged.

References

Annaert J, De Ceuster M, Verstegen K (2013) Are extreme returns priced in the stock market? European evidence. J Bank Financ 37:3401–3411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.05.015

Baars M, Mohrschladt H (2020) An alternative behavioral explanation for the MAX effect. University of Muenster, Muenster

Baker M, Wurgler J (2006) Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. J Financ 61:1645–1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00885.x

Bali TG, Cakici N, Whitelaw RF (2011) Maxing out: stocks as lotteries and the cross-section of expected returns. J Financ Econ 99:427–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.08.014

Banerjee S (2011) Learning from prices and the dispersion in beliefs. Rev Financ Stud 24:3025–3068. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhr050

Barber BM, Odean T (2008) All that glitters: the effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Rev Financ Stud 21:785–818. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhm079

Barberis N, Huang M (2008) Stocks as lotteries: the implications of probability weighting for security prices. Am Econ Rev 98:2066–2100. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.5.2066

Barth ME, Landsman WR, Raval V, Wang S (2020) Asymmetric timeliness and the resolution of investor disagreement and uncertainty at earnings announcements. Account Rev 95:23–50. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52656

Bessembinder H, Zhang F (2013) Firm characteristics and long-run stock returns after corporate events. J Financ Econ 109:83–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.02.009

Billings MB, Jennings R, Lev B (2015) On guidance and volatility. J Account Econ 60:161–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2015.07.008

Brunnermeier MK, Gollier C, Parker JA (2007) Optimal beliefs, asset prices and the preference for skewed returns. Am Econ Rev 97:159–165. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.2.159

Chan YC, Chui AC (2016) Gambling in the Hong Kong stock market. Int Rev Econ Financ 44:204–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2016.04.012

Chen H, Tang QL, Jiang YH, Lin ZJ (2010) The role of international financial reporting standards in accounting quality: evidence from the European Union. J Int Financ Manag Account 21:220–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-646X.2010.01041.x

Chen HY, Chen SS, Hsin CW, Lee CF (2014) Does revenue momentum drive or ride earnings or price momentum? J Bank Financ 38:166–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.09.021

Chen Y, Kumar A, Zhang C (2020) Searching for gambles: gambling sentiment, and stock market outcomes. J Financ Quant Anal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2635572

Cheon YH, Lee KH (2018a) Maxing out globally: individualism, investor attention, and the cross section of expected stock returns. Manag Sci 64:5807–5831. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2830

Cheon YH, Lee KH (2018b) Time variation of MAX-premium with market volatility: evidence from Korean stock market. Pacific Basin Financ J 51:32–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2018.05.007

Dorn AJ, Dorn D, Sengmueller P (2015) Trading as gambling. Manag Sci 61:2376–2393. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1979

Fama EF, MacBeth JD (1973) Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 81:607–636. https://doi.org/10.1086/260061

Fang L, Peress J (2009) Media coverage and the cross-section of stock returns. J Financ 64:2023–2052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01493.x

Fong WM, Toh B (2014) Investor sentiment and the MAX effect. J Bank Financ 46:190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.05.006

Gallo LA (2017) The more we know about fundamentals, the less we agree on price evidence from earnings announcements. University of Michigan

Gao BX, Lin TC (2015) Do individual investors treat trading as a fun and exciting gambling activity? evidence from repeated natural experiments. Rev Financ Stud 28:2128–2166. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhu075

Gervais S, Kaniel R, Mingelgrin DH (2001) The high-volume return premium. J Financ 56:877–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00349

Han B, Kumar A (2013) Speculative retail trading and asset prices. J Financ Quant Anal 48:377–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109013000100

Hung W, Yang JJ (2018) The MAX effect: lottery stocks with price limits and limits to arbitrage. J Financ Mark 41:77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finmar.2018.07.003

Jegadeesh N, Livnat J (2006) Post-earnings-announcement drift: the role of revenue surprises. Financ Anal J 62:22–34. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v62.n2.4081

Kaniel R, Liu S, Saar G, Titman S (2012) Individual investor trading and return patterns around earnings announcements. J Financ 67:639–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2012.01727.x

Ku KP (2010) Sales momentum strategies. J Manag 27:267–289. https://doi.org/10.6504/JOM.2010.27.03.04

Ku KP (2011) Earnings and sales momentum. J Manage 28:521–544. https://doi.org/10.6504/JOM.2011.28.06.01

Ku KP (2017) Monthly sales announcements and behavioral bias. Sun Yat Sen Manag Rev 25:63–100. https://doi.org/10.6160/2017.03.02

Kumar A (2009) Who gambles in the stock market? J Financ 64:1889–1933. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01483.x

Kumar A, Page JK, Spalt OG (2016) Gambling and comovement. J Financ Quant Anal 51:85–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109016000089

Lee YT, Liu YJ, Roll R, Subrahmanyam A (2004) Order imbalances and market efficiency: evidence from the Taiwan stock exchange. J Financ Quant Anal 39:327–341. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109000003094

Lin TC, Liu X (2018) Skewness, individual investor preference, and the cross-section of stock returns. Rev Financ 22:1841–1876. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfx036

Liu B, Wang H, Yu J, Zhao S (2020) Time-varying demand for lottery: speculation ahead of earning announcements. J Financ Econ 138:789–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2020.06.016

Liu YH, Tsai YC (2006) The private information trading during monthly sales announcements. J Manag Syst 13:47–76. https://doi.org/10.29416/JMS

Mitton T, Vorkink K (2007) Equilibrium underdiversification and the preference for skewness. Rev Financ Stud 20:1255–1288. https://doi.org/10.1093/revfin/hhm011

Nartea GV, Kong D, Wu J (2017) Do extreme returns matter in emerging markets? evidence from the Chinese stock market. J Bank Financ 76:189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.12.008

Nguyen HT, Truong C (2018) When are extreme daily returns not lottery? at earnings announcements! J Financ Mark 41:92–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finmar.2018.05.001

Truong C, Corrado C, Chen Y (2012) The options market response to accounting earnings announcements. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 22:423–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2012.01.006

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1992) Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. J Risk Uncertain 5:297–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00122574

Umutlu M, Bengitöz P (2017) The cross-section of expected index returns in international stock markets. In: Paper presented at 2017 infiniti conference, Valencia, pp 11–12

Walkshäusl C (2014) The MAX effect: European evidence. J Bank Financ 42:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.01.020

Yao S, Wang CF, Cui X, Fang Z (2019) Idiosyncratic skewness, gambling preference, and cross-section of stock returns: evidence from China. Pacific Basin Financ J 53:464–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2019.01.002

Zhong A, Gray P (2016) The MAX effect: an exploration of risk and mispricing explanations. J Bank Financ 65:76–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.01.007

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yi-Hua Su for enhancing the quality of the work. Zi-Mei Wang acknowledges the financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant number: MOST 108-2410-H-130 -005).

Funding

Zi-Mei Wang acknowledges the financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant number: MOST 108-2410-H-130 -005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZW: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Visualization; Roles/Writing–original draft. DL: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Roles/Writing–original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there are no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

-

1.

Standardized revenue surprise (SUS)

We follow the approach of Ku (2011) using the seasonal random walk with drift to calculate the expected revenue. The equation used was E(Si,t) = μS,i,t + Si,t-12, in which Si,t and Si,t−12 represent the revenue of stock i in month t and month t − 12, respectively. Furthermore, E(Si,t) represents the expected revenue of stock i in month t; μS,i,t is the drift. Based on this model, we obtain the estimated value for expected revenue and further standardize the revenue surprise (SUSi,t) using the following formula:

where μS,i,t and σS,i,t are the mean and standard deviation, respectively, of stock i’s revenue variation in the first 24 months (Si,t− Si,t−12).

-

2.

Extreme returns (MAX)

The maximum daily returns (MAX) within a month. This measurement refers to the approach of Bali et al. (2011), where MAX(k) is the mean of k number of maximum daily returns (MAX) in the previous month (k = 1,2…5).

-

3.

Modified extreme returns (LHR)

This variable is defined as the difference between the days hitting upper limits and the days reaching lower limits in a month and then divided by the number of trading days. At the end of month t, we classify the stocks into high LHR (high modified MAX) and low LHR (low modified MAX) groups on the basis of the 80th percentile of the LHR in the previous month. We use the LHR as a proxy for the modified MAX. We require a minimum of 10 observations within a month to calculate the LHR.

-

4.

The net intensity of limit hits during the revenue announcement period (MRA)

MRA is defined as the difference between the days hitting upper limits and the days reaching lower limits during a five-day around surrounding revenue announcements divided by total trading days in a month.

-

5.

Revenue information–related LHR (RA_LHR)

If MRA is at least as large as the LHR, and MAX(1) should occur within a five-day window around revenue announcements, this suggests that the LHR is mainly driven by revenue information, and we call it RA_LHR; otherwise, it is NORA_LHR.

-

6.

The monthly revenue announcement is good news (GOOD)

GOOD and BAD are dummy variables. For each month, we classify stocks into three portfolios, namely high, medium, and low, based on their SUS; if a stock belongs to the highest SUS group, then GOOD is 1; otherwise, it is 0. Similarly, if a stock belongs to the lowest SUS group, then BAD is 1; otherwise, it is 0.

-

7.

Idiosyncratic volatility (IVOL)

Following Hung and Yang (2018), the daily return rate of the previous month is employed to run the Fama–French three-factor alpha model. Individual stocks are required to be active for at least 10 trading days in the month for IVOL. Subsequently, the second-moment of the residual is defined as the IVOL.

-

8.

Systematic risk (BETA)

BETA refers to systematic risk and is determined using the measurement method of Dimson (1979), which involves taking the daily stock returns as the dependent variable for each month and utilizing the market returns of the same day with a lag and lead of one day each as the independent variables to conduct a regression and adding all BETAs together.

where ri,d is the return on stock i on day d, rm,d is the market return on day d, and rf,d is the risk-free rate on day d. The market beta for stock i in month t is defined as \(\hat{\beta }_{i} = \hat{\beta }_{i,1} + \hat{\beta }_{i,2} + \hat{\beta }_{i,3}\).

-

9.

Size (MV, NT$ 1 million)

Company size (MV) refers to the market value of equity of a company at the previous month end.

-

10.

Prior returns (PR01)

PR01 is defined as the previous month’s returns.

-

11.

Prior returns (PR12)

PR12 is defined as the 12 month return (skip the most recent month) of a firm at the month end prior to the portfolio formation.

-

12.

Turnover (TURN)

TURN is the ratio of monthly trading volume to shares outstanding at the month end prior to the portfolio formation.

-

13.

Price-to-book equity (PB)

PB denotes the stock price divided by the book value of equity per share as reported at the end of the most recent fiscal year.

-

14.

Amihud illiquidity (ILLQ)

ILLQ is defined as the ratio of the absolute value of stock returns in the dollar trading volume per month multiplied by a factor of 104.

-

15.

Relative bid-ask spread (SPREAD)

SPREAD measures the average ratio of bid-ask spread in bid-ask midpoint per month.

-

16.

The net intensity of limit hits during earnings announcement period (QEA)

QEA is defined as the difference between the days hitting upper limits and the days reaching lower limits during a five-day window surrounding the earnings announcement divided by the total trading days in a month.

-

17.

Earnings information–related LHR (EA_LHR)

If QEA is at least as large as the LHR and MAX(1) occurs within a five-day window around earnings announcements, this suggests that the LHR is mainly driven by earnings information, and we call it EA_LHR; otherwise, it is NOEA_LHR.

-

18.

Construction of lottery index (LIDX)

Lottery investors are more likely to be attracted by certain stock types, such as stocks with low prices, high idiosyncratic volatility, or high idiosyncratic skewness. Following Kumar et al. (2016), we create a composite lottery index (LIDX) to combine the three lottery characteristics into one measure. First, all stocks are independently ranked into 20 groups by the stock price (from high to low), idiosyncratic volatility (from small to large), and idiosyncratic skewness (from small to large) at the end of month t. The top vigintile consists of stocks with the lowest price, the highest volatility, and the highest skewness. Next, we add the three group ranks for each stock to produce a score ranged between 3 and 60. Finally, these values are scaled according to the formula of LIDX = (score−3)/(60–3) to obtain the individual stock’s lottery index, which is between 0 and 1. For example, if one stock falls under Group 11 of ISKEW, Group 20 of IVOL, and Group 20 of Price, the total score for that stock is 51 (11+20+20), and the scaled lottery index (LIDX) is 0.84 [(51−3)/(60−3)]. The higher the index, the more lottery-like the stock is, and the more it attracts investors who prefer speculation and gambling.

-

19.

The proportion of individual investor trading (IOP)

IOP is defined as the average ratio of daily individual investor orders over total orders for each month.

-

20.

The marketable order imbalance by each investor type (OI)

We calculate the marketable order imbalance by each investor type (OIi,t,k)as a proxy for price pressure. For stock i in month t, the marketable order imbalance is defined as the average ratio of daily difference between marketable buy and sell order volumes submitted by investor group k to the total order volume, where k = 1, 2, 3, 4, representing foreign investors, mutual funds, other institutions, and individual investors, respectively.

Appendix 2: Event study

This paper uses the event study method to analyze the information content of monthly revenue announcements. The revenue announcement date is set as the event day (d = 0), and the event window starts five trading days prior to the announcement date and ends five days after the announcement (d =− 5 to + 5). We use the CAR during the event window to measure the stock price response to the monthly revenue announcement. The cumulative abnormal return \(CAR_{i,t} \left( {a,b} \right)\) of stock i from day a to day b during the event window of the announcement in period t is calculated as follows:

where ARi,s is the abnormal return (AR) of stock i on day s; ri,s is the return of stock i on day s; and E(ri,s) is the return on the benchmark portfolio of stock i on day s. Following Ku (2011) and Jegadeesh and Livnat (2006), at the end of each month, the size and book-to-market ratio are used to construct nine equally weighted portfolios based upon the intersection of three size categories and three book-to-market-ratio-based categories.Footnote 32,Footnote 33 The benchmark for a stock is the particular portfolio among the nine benchmark portfolios to which that stock belongs.

For the standardized revenue surprise, we refer to Ku (2011) and use the seasonal random walk with drift to calculate the expected revenue. Specifically, \(S_{i,t} = \mu_{S,i,t} + S_{i,t - 12}\), where \(S_{i,t}\) and \(S_{i,t - 12}\) are the revenues of stock i in month t and month t− 12, respectively; \(\mu_{S,i,t}\) is the drift. The standardized revenue surprise \(\left( {SUS_{i,t} } \right)\) is calculated as follows:

where \(\hat{\mu }_{S,i,t}\) and \(\hat{\sigma }_{S,i,t}\) are the mean and standard deviation of the revenue variations \(\left( {S_{i,t} - S_{i,t - 12} } \right)\) of stock i in the previous 24 months, respectively.

To investigate the information content of monthly revenue announcements, we rank stocks by SUS and classify them into three groups, i.e., high (top one third), medium (middle one third), and low (bottom one third). Stocks with high SUS indicate good monthly revenue news (G), stocks with medium SUS indicate no news (N), and stocks with low SUS indicate bad news (B). Next, we calculate the average AR and average CAR of each group for 5 days before and after the announcement (d = − 5 to + 5). If monthly revenues convey fundamental information about the concerned company, the favorable (unfavorable) news would have a positive (negative) effect on stock price. In other words, SUS is significantly positively associated with CAR.

Appendix 3: Supplementary data and robustness tests

See Tables 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, ZM., Lien, D. Is maximum daily return a lottery? Evidence from monthly revenue announcements. Rev Quant Finan Acc 59, 545–600 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01051-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01051-1