Abstract

This paper seeks to explain time-varying correlations among equity returns. The literature has shown that fundamental and economic factors can explain stock returns or the volatility of markets. Here, panel data analysis is employed to examine whether these factors can also explain the comovement of stock returns. Time-varying correlations among sectoral indexes are estimated using a restricted multivariate threshold GARCH model with dynamic conditional correlation controlling for the asymmetric effects of news and the influence of financial crises. The empirical results from this panel data analysis show that equity return correlations can be explained not only by macroeconomic variables but also by fundamentals within an industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hassan and Malik (2007) used the daily close returns for the financial, industrial, consumer (services), health, energy (oil and gas), and technology sectors in their analysis. When they tried a four-variable GARCH model the system didn’t converge. Therefore, they estimated two trivariate BEKK-GARCH: one for the consumer, financial and technology sectors and the other for the energy, health and industrial sectors. They documented significant transmissions of shocks and volatility among consumer, financial and technology sectors and among energy, health and industrial sectors.

By the end of 2006, the number of companies listed on the ASE had reached 227 indicating an increase in market depth as well as the diversity of investment opportunities provided (ASE Annual Report 2006). The rise in the prominence of the ASE has occurred at the same time as a number of regulatory changes and new listing requirements have been introduced (ASE Annual Report 2012). The ASE adopted a new sector classification that was in line with international standards and reflected a more “accurate” image of the listed companies to investors in terms of the nature of the work. The Standard and Poor’s classification has been adopted with some changes to accommodate the unique features of Jordanian companies. Listed companies are regrouped into three main sectors (financial, industrial and services sectors) with 23 sub-sectors.

These sectoral equity indices are based on the free float shares, whereby the index is calculated using the market value of the free float shares of the companies and not the total number of listed shares of each company.

Specifically, all of the 23 sectors in the ASE under the new industry group were ranked according to (1) their percentage of the total market capitalisation and (2) their number of constituent firms. Both rankings were jointly used to identify the top 10 most important sectors (by size) for the ASE.

The ASE retroactively calculated sectoral equity indices of the new industry grouping for all sectors back to 2000 except for the telecommunication sector which was only calculated back to 2003.

According to Miller and Blair (1985), the backward linkages of a sector indicate that an expansion in its production is valuable to the economy as it causes a rise in productive activities of other sectors. On the other hand, the forward linkages of a sector indicate that its production is sensitive to changes in other sectors’ output.

For example, the APT developed by Ross (1976) asserts that asset returns are related in a linear fashion to k-different orthogonal risks, which arise from shocks to macroeconomic factors. Therefore, the k-different risk factors and their sensitivities can be the main source of correlation among returns.

The Statistics and Publication Division, under the Research and International Relations Department of the ASE, calculated these ratios. The ratios are available at http://ase.com.jo/en/node/543.

The Statistics and Publication Division calculates up to 16 financial ratios for different industries; however, these are not uniformly available across sectors. Only 10 financial ratios were common across all the sample industries (see Table 9 of Appendix).

Imports of goods and non-factor services of Jordan were estimated at 72% of total consumption in 2011 (World Bank 2013).

Huang et al. (2010) documented that the forecasting performance of the DCC-GARCH model is better than that of the GARCH-BEKK model. While the ADCC model of Cappiello et al. (2006) incorporates the leverage effect of shocks in the conditional correlation, Laurent et al. (2012) employing data for 10 stocks from five different sectors of the NYSE documented that the forecast of this ADCC model is not significantly better than that of the Engle’s (2002) DCC model with the leverage effect in the conditional variance.

The results from VAR(1) in Table 11 of Appendix indicate that equity returns for the ASE sectors are mainly predictable from their own historical share prices changes; there are only a few cases where return changes from other sectors have an influence. An AR(1) process was therefore chosen for the mean equation instead of VAR(1). The reduction in parameters also helps getting a convergent estimation for the DCC-MTGARCH (1,1) for 10 sectors.

The ASE market capitalization weighted index is calculated using the pre-2006 industry categories, but the ASE free float index is calculated using the new industry categories introduced in 2006. The Chow breakpoint test was therefore performed using the ASE free float index.

The Chow breakpoint test was conducted to determine the dates of structural changes. The findings indicated structural changes at three points: November 8, 2005, December 17, 2006, and June 18, 2008.

Three panel data models, namely the pooled regression model, the fixed effect model and the random effect model, were first estimated. In order to determine which of the three models is the most appropriate for the analysis, the Hausman test was applied. The test result showed that the fixed effect model was the appropriate specification (see Sect. 5.4).

Evidence suggesting that it is reasonable to use annual data when analysing time varying correlations is provided by several studies such as David and Simonovska (2016).

The results of a correlation test indicated that the PCs of any two sectors are independent, so the products of PCs are used instead of the average values of PCs. The test results are available upon request from the authors.

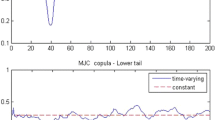

The likelihood ratio statistic in Panel C of Table 4 suggests that the DCC model used in this paper performs better than a CCC model.

The conditional correlations of sectoral return seem to be associated with a number of common factors. One of these, for example, is inflation; there is a positive relationship between inflation and the conditional correlation among sectoral stock returns. The correlation values between these two variables are positive in 44 out of 45 instances; the only instance of a negative correlation is between the conditional correlation between BNK and MIX (ρ1,10) and inflation where a value of −0.10 is documented. For all other correlations, the values range from a low of 0.19 between inflation and the conditional correlation between INS and RES (ρ2,4) to a high of 0.69 between inflation and the conditional correlation between EDS and FOB (ρ5,9).

In addition, we estimate the fixed effect model without interaction terms; the estimation result is shown as Model 4 in Table 7.

Nonetheless, the likelihood ratio statistic reported in Table 8 suggests that the growth PC is an important factor that can explain conditional correlations between sectoral returns earned in the ASE.

The likelihood ratio statistics reported in Table 8 confirm that macroeconomic variables are important determinants of the correlations of stock index returns and that there are significant interactions between sector-specific and economic factors.

References

Abdmoulah W (2010) Testing the evolving efficiency of Arab stock markets. Int Rev Financ Anal 19:25–34

Ahid M, Augustine A (2012) The impact of global financial crisis on Jordan. Int J Bus Manag 7:80–88

Al-Fayoumi NA, Khamees BA, Al-Thuneibat AA (2009) Information transmission among stock return indexes: evidence from the Jordanian stock market. Int Res J Finance Econ 1:194–208

Al-Jarrah IM, Khamees BA, Qteishat IH (2011) The “turn of the month anomaly” in Amman Stock Exchange: evidence and implications. J Money Invest Bank 21:5–11

Allen F, Gale D (2000) Financial contagion. J Polit Econ 108:1–33

Alomari M (2015) Market efficiency and volatility spillovers in the Amman Stock Exchange: a sectoral analysis. Dissertation, University of Dundee

Al-Saket B (2007) Secretes of falling stock prices in the stock market. Al-Hadath, Amman (Translated from Arabic to English)

AlZoubi OM, Al-Darkazaly WA (2013) Inter-sectoral linkages in Jordan economy: input–output analysis. Glob J Manag Bus Res Finance 13:34–42

Al-Zoubi H, Al-Zu’bi B (2007) Market efficiency, time-varying volatility and the asymmetric effect in Amman Stock Exchange. Manag Finance 33:490–499

Amini H, Cont R, Minca A (2016) Resilience to contagion in financial networks. Math Finance 26(2):329–365

ASE (2013) Amman Stock Exchange [online]. www.ase.com.jo

Baele L (2005) Volatility spillover effects in European equity markets. J Financ Quant Anal 40:373–401

Baur DG (2012) Financial contagion and the real economy. J Bank Finance 36:2680–2692

Bekaert G, Hodrick RJ, Zhang X (2009) International stock return comovements. J Financ 64:2591–2626

Bekaert G, Harvey CR, Lundblad CT, Siegel S (2011) What segments equity markets? Rev Financ Stud 24:3841–3890

Billio M, Caporin M, Frattarolo L, Pelizzon L (2016) Network in risk spillovers: a multivariate GARCH perspective. Department of Economics Working Paper no. 03/WP/2016, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

Binder JJ, Merges MJ (2001) Stock market volatility and economic factors. Rev Quant Finane Acc 17:5–26

Binici M, Koksal B, Orman C (2013) Stock return comovement and systemic risk in the Turkish banking sector. Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Working Paper no. 13/02, Ankara

Bollerslev T, Wooldridge JM (1992) Quasi-maximum likelihood estimation and inference in dynamic models with time-varying covariances. Econom Rev 11:143–172

Cappiello L, Engle RF, Sheppard K (2006) Asymmetric dynamics in the correlation of global equity and bond returns. J Financ Econom 4(4):537–572

Chiang TC, Chen X (2016) Empirical analysis of dynamic linkages between China and international stock markets. J Math Finance 6:189–212

Chiang TC, Jeon BN, Li H (2007) Dynamic correlation analysis of financial contagion: evidence from Asian markets. J Int Money Finance 26:1206–1228

Chiang TC, Lao L, Xue Q (2015) Comovements between Chinese and global stock markets: evidence from aggregate and sectoral data. Rev Quant Finance Acc (Forthcoming)

Chuang IY, Lu JR, Tswei K (2007) Interdependence of international equity variances: evidence from East Asian markets. Emerg Mark Rev 8:311–327

Claessens S, Forbes K (2013) International financial contagion. Springer, Berlin

David JM, Simonovska I (2016) Correlated beliefs, returns, and stock market volatility. J Int Econ 99:S58–S77

De Nicolo G, Kwast ML (2002) Systemic risk and financial consolidation: Are they related? J Bank Finance 26:861–880

Dunteman GH (1994) Principal components analysis. In: Lewis-Beck MS (ed) Factor analysis and related techniques, international handbooks of quantitative applications in the social sciences, 5. Sage Publications, London, pp 157–245

Eiling E, Gerard B, Hillion P, De Roon FA (2012) International portfolio diversification: currency, industry and country effects revisited. J Int Money Finance 31:1249–1278

El-Nader HM, Alraimony AD (2012) The impact of macroeconomic factors on Amman stock market returns. Int J Econ Finance 4:202–213

Engle RF (2002) Dynamic conditional correlation: a simple class of multivariate general autoregressive conditional heretoskedasticity models. J Bus Econ Stat 20:339–350

Fama EF (1970) Efficient capital markets: a review of theory and empirical work. J Finance 25:383–417

Fama EF, French KR (1992) The cross-section of expected stock returns. J Finance 47:427–465

Fama EF, French KR (2015) A five-factor asset pricing model. J Finance Econ 116(1):1–22

Fayyad A, Daly K (2011) International transmission of stock returns: mean and volatility spillover effects in the emerging markets of the GCC countries, the developed markets of UK & USA and oil. Int Res J Finance Econ 67:103–117

Fifield SGM, Power DM, Sinclair CD (2002) Macroeconomic factors and share returns: an analysis using emerging market data. Int J Finance Econ 7:51–62

Forbes KJ, Rigobon R (2002) No contagion, only interdependence: measuring stock market comovements. J Finance 57(5):2223–2261

Gallagher LA, Twomey CE (1998) Identifying the source of mean and volatility spillovers in Irish equities: a multivariate GARCH analysis. Econ Soc Rev 29:341–356

Garcia R, Mantilla-Garcia D, Martellini L (2015) A model-free measure of aggregate idiosyncratic volatility and the prediction of market returns. J Finance Quant Anal (Forthcoming)

Group of Ten (2001) Report on consolidation in the financial sector. IMF, Washington

Hamao Y, Masulis RW, Ng V (1990) Correlations in price changes and volatility across international stock markets. Rev Financ Stud 3:281–307

Hammoudeh SM, Yuan Y, McAleer M (2009) Shock and volatility spillovers among equity sectors of the Gulf Arab stock markets. Q Rev Econ Finance 49:829–842

Harris RDF, Pisedtasalasai A (2006) Return and volatility spillovers between large and small stocks in the UK. J Bus Finance Acc 33:1556–1571

Hassan SA, Malik F (2007) Multivariate GARCH modeling of sector volatility transmission. Q Rev Econ Finance 47:470–480

Hernández LF, Valdés RO (2001) What drives contagion: trade, neighborhood, or financial links? Int Rev Financ Anal 10:203–218

Ho C, Lee C, Lin C, Wang E (2005) Liquidity, volatility and stock price adjustment: evidence from seasoned equity offerings in an emerging market. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Polic 8:31–51

Huang Y, Su W, Li X (2010) Comparison of BEKK GARCH and DCC GARCH models: an empirical study. In: Cao L, Zhong J, Feng Y (eds) Advanced data mining and applications part II, vol 6441., Lecture Notes in Computer ScienceSpringer-Verlag, Berlin

Kaiser HF (1960) The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas 20:141–151

Kanas A (1998) Volatility spillovers across equity markets: european evidence. Appl Financ Econ 8:245–256

Khan MN, Tantisantiwong N, Fifield SGM, Power DM (2015) The relationship between South Asian stock returns and macroeconomic variables. Appl Econ 47:1298–1313

Kim MH, Sun L (2016) Dynamic conditional correlations between Chinese sector returns and the S&P500 index: an interpretation based on investment shocks. Asian Finance Association 2016 Conference. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2713602

Kolluri B, Wahab M (2008) Stock returns and expected inflation: evidence from an asymmetric test specification. Rev Quant Finance Acc 30:371–395

Laurent S, Rombouts JVK, Violante F (2012) On the forecasting accuracy of multivariate GARCH models. J Appl Econ 27:934–955

Li H (2007) International linkages of the Chinese stock exchanges: a multivariate GARCH analysis. Appl Financ Econ 17:285–297

Li H, Majerowska E (2008) Testing stock market linkages for Poland and Hungary: a multivariate GARCH approach. Res Int Bus Finance 22:247–266

Ling S, McAleer M (2003) Asymptotic theory for a vector ARMA-GARCH model. Econom Theor 19:280–310

Mackey R (2013) Remembering the start of Syria’s uprising. The New York Times, New York

Maghyereh A (2005) Electronic trading and market efficiency in an emerging market. Emerg Mark Finance Trade 41:5–19

Maghyereh A, Awartani B (2012) Return and volatility spillovers between Dubai financial market and Abu Dhabi stock exchange in the UAE. Appl Financ Econ 22:837–848

Malik F, Hammoudeh S (2007) Shock and volatility transmission in the oil, US and Gulf equity markets. Int Rev Econ Finance 16:357–368

Malik F, Hassan SA (2004) Modeling volatility in sector index returns with GARCH models using an iterated algorithm. J Econ Finance 28:211–225

Miller RE, Blair PD (1985) Input–output analysis: foundations and extensions. Prentice-Hall Inc, Englewood Cliffs

Mousa NYA (2010) Monetary policy and the role of exchange rate: the case of Jordan. Dissertation, The University of Birmingham

Mun K-C (2012) The joint response of stock and foreign exchange markets to macroeconomic surprises: using US and Japanese data. J Bank Finance 36:383–394

Ng A (2000) Volatility spillover effects from Japan and the US to the Pacific-Basin. J Int Money Finance 19:207–233

Omet G, Khasawneh M, Khasawneh J (2002) Efficiency tests and volatility effects: evidence from the Jordanian stock market. Appl Econ Lett 9:817–821

Patro DK, Qi M, Sun X (2013) A simple indicator of systemic risk. J Financ Stab 9(5):105–116

Phylaktis K, Xia L (2009) Equity market comovement and contagion: a sectoral perspective. Financ Manag 38(2):381–409

Pritsker M (2001) The channels for financial contagion. In: Claessens S, Forbes K (eds) International financial contagion. Springer, Berlin

ASE Annual Report (2006) Amman Stock Exchange annual report. http://www.ase.com.jo/en/node/536. Accessed 28 Feb 2012

ASE Annual Report (2012) Amman Stock Exchange annual report. http://www.ase.com.jo/en/node/536. Accessed 11 Jan 2013

Riedle T (2016) Measuring the contribution to systemic risk of sectors in the United States, the UK and Germany using ΔCoVaR. SSRN Working paper. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2741294

Ross SA (1976) The arbitrage theory of capital asset pricing. J Econ Theory 13:341–360

Simmons P, Tantisantiwong N (2014) Equilibrium moment restrictions on asset returns: normal and crisis periods. Eur J Finance 20:1064–1089

Sok-Gee C, Abd Karim MZ (2010) Volatility spillovers of the major stock markets in ASEAN-5 with the U.S. and Japanese stock markets. Int Res J Finance Econ 44:161–173

Theodossiou P, Lee U (1993) Mean and volatility spillovers across major national stock markets: further empirical evidence. J Financ Res 16:337–350

Vidal-García J, Vidal M, Nguyen DK (2016) Do liquidity and idiosyncratic risk matter? Evidence from the European mutual fund market. Rev Quant Finance Acc 47:213–247

Walter JE (1956) Dividend policies and common stock prices. J Finance 11:29–41

Wang Z, Kutan AM, Yang J (2005) Information flows within and across sectors in Chinese stock markets. Q Rev Econ Finance 45:767–780

World Bank (2003) The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan country assistance evaluation, Report No.26875-JO. Accessed 16 May 2014

World Bank (2013) Jordan economic monitor: maintaining stability and fostering shared prosperity amid regional turmoil. Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit, Middle East and North African Region. The World Bank. www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/MNA/Jordan_EM_Spring_2013.pdf. Accessed 25 March 2014

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere thanks for helpful comments from those who attended the British Accounting and Finance Association Scottish area group conference held at the University of St Andrews, United Kingdom and the Southampton Business School Seminar series. The first author would also like to thank the German Jordanian University for funding which allowed him to undertake this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alomari, M., Power, D.M. & Tantisantiwong, N. Determinants of equity return correlations: a case study of the Amman Stock Exchange. Rev Quant Finan Acc 50, 33–66 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0622-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0622-4

Keywords

- Equity returns correlations

- Risk factors

- Multivariate threshold GARCH

- Dynamic conditional correlation

- Panel data analysis