Abstract

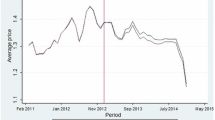

We investigate whether the cost pass-through in the European retail gasoline market is the same regardless of whether cost changes are driven by exchange rate fluctuations or driven by fluctuations in the dollar spot price of gasoline. We find that the two cost pass-through rates are not the same: we find that the latter exceeds the former. The effect is quantitatively small, but robust and statistically significant. This pattern is not due to a lower persistence of exchange rate changes, refinery supply contracts, or economic fluctuations. The lower variability of exchange rates relative to that of oil prices explains a portion of the response gap. A possible explanation for the remaining gap is that consumers draw a direct link between the crude oil and retail gasoline prices, which affects their price expectations and their search intensity, and thus the retailers’ pass-through. Because pass-through is sometimes used to assess market competitiveness and contributes to the forecast of the Consumer Price Index, it is important to recognize that the source of variation in the underlying costs may have an effect on the assessment of market conduct and inflation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Meyler (2009) points out, energy consumption accounts for 20% of consumer expenditure in the European Union countries. With the volatility of energy prices being approximately an order of magnitude higher than those of other consumer goods, energy price changes account for about half of the volatility of the Consumer Price Index.

For example, Yang (1997) uses data for 87 manufacturing sectors in the US over the 1980–1991 period and finds that the degree of pass-through is positively correlated with product differentiation and negatively correlated with the elasticity of marginal cost. The impact of market structure on the ERPT is also highlighted more recently by Auer and Schonle (2016).

Of interest to the present study is Hahn (2003), who finds that approximately a fifth of the inflation variability in Euro countries is due to fluctuations in the price of oil expressed in dollars, and approximately another fifth is due to exchange rate fluctuations. Interestingly, the exchange rate effects feed through faster to the inflation rate than do changes in the oil price.

An older study by Galeotti, Lanza, and Manera (2003) decomposes the adjustment process into an upstream adjustment (which includes the exchange-rate effect) and a retail adjustment (which is in domestic currency).

Additional recent work on response asymmetries of the retail price to upstream shocks include Chen, Huang, and Ma (2017), who show that it is present in the Chinese market (and that such a pattern might have political implications), and Ogbuabor et. al. (2018), who show that it is absent in the South Africa motor fuels market (possibly because the market is regulated by the government).

Though this study focuses on the pricing of retail gasoline, we could have investigated the same questions with regards to diesel: a fuel that is at least as important in Europe as is motor gasoline. There are, however, some reasons why we chose to study the gasoline market: Globally, gasoline is the pre-eminent motor fuel with a very thick global market. More economic analysis is devoted to the study of gasoline pricing than to the price of diesel pricing. A bit more subtly, Europe has a bigger “footprint” in the market for diesel, and thus demand shocks of large European countries might have an influence of the global price of diesel, whereas they would be unlikely to do so for gasoline.

Through the paper, \({a}_{j}\) and \({a}_{s}\) are estimated via fixed effects. Results without the incorporation of seasonal effects are quantitatively almost indistinguishable to those that include them.

We believe that this is reasonable; but in principle one could decompose the domestic price into an exchange rate component and a dollar price component in the cointegrating vector as well. It turns out that doing so yields minimal difference in the impulse response functions compared to those using Eq. (6).

Notice that each term of the summation has the same units, regardless of the units in which currencies and prices are measured in.

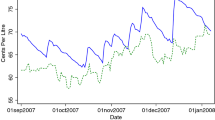

The source of the retail data is the Weekly Oil Bulletin (http://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/data-analysis/weekly-oil-bulletin). The retail price quote for a week corresponds to a Monday, and it is based either on an average of quotes that are obtained over the preceding week, or on reports that are obtained for that same day. In the country-by-country analysis, the response profile for the two sets of countries will be off by about half a week, but the shape will not be affected. When we average over all countries, the intercept shift should be only one or two days. Details of the sampling scheme for each country are contained in the Bulletin.

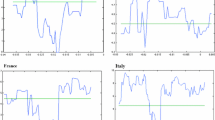

The countries in this study consist of Eurozone members Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain, and non-Euro countries (as of 2015) Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The partition of countries into Euro and non-Euro members is relevant only for the subsample analysis that is reported in this paper.

All prices are in nominal units, as is the case for most gasoline pricing research. The price adjustment process takes place over the space of two months, over which changes in the price level are insignificant. Moreover, inflation rates are only available at quarterly or annual frequency.

We use the Platts high FOB Rotterdam Barge series, which is used by some oil companies to compute suggested prices (Faber and Janssen, 2019).

https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pri_spt_s1_d.htm. The data frequency for these series is weekly, but a daily series is also available and allows us to ascertain how the aggregation to the weekly series is implemented. Using a crude oil price, e.g., that of Brent, is less appropriate because it is further up the supply chain and has a smaller explanatory power in terms of explaining retail gasoline price movements as measured by the R-squared of the price adjustment equations. Moreover, crude is not a homogeneous product, and not all grades move in lock step in terms of price.

ECU refers to the European Currency Unit, which was introduced in 1979 as a precursor of the Euro, and was a composite of European Union currencies.

Note that when countries join the euro, their exchange rate with respect to the USD changes discontinuously. We address this issue by converting the pre-euro national currencies of countries that eventually joined the euro into “euro equivalents” based on the exchange rate at the euro accession date. This ensures continuity at the time of accession, while preserving the relative exchange rates of these currencies prior to accession. Perhaps the best way to think of this that we have, for example, a “German Euro” and an “Italian Euro.” The two are identical to each other after both countries have joined the Euro, but they evolved differently before the joining date according to the relative exchange rate of the Mark and the Lira.

These are obtained from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database). The GDP figures are provided by Eurostat in Euro or its precursor; for non-Euro countries, Eurostat converts to Euros using current exchange rates. The HCPI measures the change over time of the prices of consumer goods and services that are acquired by households and gives comparable measures of inflation for the EU countries.

Eurostat trade data are available for 2000 onwards. Because we used a one-year lag of the measure of trade exposure, the analysis that uses these data is limited to the 2001–2015 period.

We have performed Dickey-Fuller unit root tests on all relevant series. We cannot reject the null of unit root for the retail price series, either in levels or in logs, for any of the EU countries. Neither can we reject the null of unit root for the Rotterdam price, either in levels or in logs, for any of the sub-periods that correspond to a EU country’s data sample. Finally, cointegration between Rotterdam and retail prices cannot be rejected for all but one of the countries.

Significance levels are based on Wald tests (t-statistics). The cointegrating relationship imposes the same pass-through as time goes to infinity (a reasonable constraint based on economic reasoning).

This approach is conservative in the sense that it generates larger standard errors. For each week, we also draw the full set of lagged values to account for dynamic effects. Because the residual is generally not serially correlated, we do not need to account for other sources of time-series dependence. The bootstrap consists of 200 replications; and for each of them, we estimate all specifications and the associated impulse response functions.

Since the statistical significance refers to the difference between the two impulse response functions, the sets of markers for two series are the same.

The country dummy variables are (of course) dropped from these specifications. We do not estimate these models for Croatia, for which our time series is very short, the coefficients are estimated imprecisely, and impulse response functions are extremely noisy, especially when obtained via bootstrapping entire cross-sections from the full sample.

We have computed the ratio of the Rotterdam price to the pre-tax retail price for each observation, and its average value in our data is equal to 0.7. Therefore, a pass-through elasticity of 0.6 to the pre-tax price is broadly consistent with a pass-through of about 0.9 in levels.

Genakos and Pagliero (2022) show that in Greek islands with many gas stations, the pass-through is equal to 1, but in islands with a single station the pass-through is around 0.6.

As a robustness exercise, we repeat the analysis with the use of the New York harbor price of wholesale gasoline, which is globally the largest market for the fuel. The regression results, which are available upon request, show a somewhat more sluggish response of the retail price and somewhat higher standard errors – possibly because the New York price, though highly correlated with the Rotterdam price, is a bit less tightly coupled with European retail prices. Moreover, the impulse response functions are quite similar to those that are obtained with the use of the Rotterdam price, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

This approach has the advantage of being easy to implement and of imposing on the data the premise that small fluctuations lead to smaller responses in a transparent way. More sophisticated but harder to implement approaches – such as those in Mann (2016) – endogenize the size of the inactivity band, link it to profit margins, and distinguish between the various stages of distribution. The latter two extensions are not feasible in our sample because we don’t observe the wholesale price.

We have also compared the regression coefficients of the threshold and “base” specifications for the panel specifications via a Seemingly Unrelated Regression system. In doing so, we are forced to forgo standard error clustering, which results in smaller standard errors. Despite this, the joint test of the difference between the parameters of the threshold model and those of the base model is not statistically significant at the 5% level for the log specification.

Importantly, the difference between the two pass-through impulse response profiles (and the associated statistical significance) is not monotonically decreasing with the threshold value, which increases our confidence that the differential response is not driven by non-linearities.

We have also re-estimated the log EC model specifications while allowing for threshold effects in the error correction term itself, and in particular setting the error correction term to zero if its value is less than one percent of the retail price. The results are indistinguishable from those with the specification that incorporates threshold effects only for the short-run dynamics.

In this analysis, a country that has eventually used the Euro is considered a Euro-adopter even prior to its switch to that currency. This is done because the exchange rates of Euro-adopters fluctuated only around small bands prior to when they joined the common currency. However, the same results are obtained if we classified countries based on whether they were using the Euro on each specific point in time. Repeating the analysis for all countries but limiting ourselves to the post-2000 period (when the Euro was in circulation) yields similar (in fact a bit larger) differences in the pass-through rates.

A separate Euro-related consideration is whether the transition to the Euro itself has had a differential impact on the pass-through profiles – perhaps by increasing retail price volatility. This one-time increase in volatility could arise because of different price rounding and different reference price points under the new currency – coupled with reactions by competing stations. We have repeated the analysis by re-estimating the models in Figs. 1 and 2 after removing the two-month period around the switchover of a country to the Euro in its retail transactions. The results are nearly identical. In the very few instances that statistical significance differs between the two sets of results, it is higher in the sample that omits the transition period – which is consistent with the expectation that the transition increased noise.

EU countries, with the exception of the UK, are not major oil producers, so a change in the oil price should not feed into their economic growth. In any event, re-estimating our specifications only for the UK yields the same empirical regularities.

Statistical significance across all four EC models and the DL models at the 20% level occurs 40% of the time and is nearly evenly split in terms of signs.

There is also an effect from changes in oil prices to GDP; e.g., see Kilian (2008). However, this effect is measurable only for large oil price shocks, and its time profile extends far beyond the pass-through adjustment periods.

Several studies, based on a wide range of methodological approaches, have observed no evidence of asymmetries in Europe (Clerides, 2010; Gautier and Le Saout, 2015; Karagiannis et al., 2015; Kristoufek and Lunackova, 2015; Venditti, 2013). Additionally, meta-analysis has revealed that European responses are less asymmetric (Perdiguero-Garcıa, 2013). The difference in the results between studies that use US data versus those that use European data is even larger when one compares studies that are similar to each other in terms of the metrics used. One reason why asymmetries are less prevalent in Europe may be that the mix of vendors differs relative to the US. For example, most of the French retail outlets are in supermarkets and hypermarkets, which charge lower prices and have quicker pass-through rates (Gautier and Le Saout, 2015). This pattern is prevalent elsewhere in Europe. In the US, during the same period, stand-alone gas stations (some with small convenience stores) dominate the sample. Supermarkets focus on competitive fuel pricing in order to attract customers for groceries, and many may choose not to exploit pricing power through asymmetric pricing strategies.

The model is based on expectations that are driven by the serial correlation of cost shocks; but it is straightforward to apply it to expectations that are driven by the observability of concurrent proxies for these costs – such as the price of oil and the exchange rate. Incomplete pass-through may also arise from tacit collusion between firms. However, sophisticated actors, such as oil companies, would treat changes in costs symmetrically regardless of its underlying cause.

References

Aguirre, I., Cowan, S., & Vickers, J. (2010). Monopoly price discrimination and demand curvature. American Economic Review, 100, 1601–1615.

Anderson, S. T., Kellogg, R., & Sallee, J. M. (2013). What do consumers believe about future gasoline prices? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 66, 383–403.

Anderson, S. T., Kellogg, R., Sallee, J. M., & Curtin, R. T. (2011). Forecasting gasoline prices using consumer surveys. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 101, 110–114.

Antoniou, F., Fiocco, R., & Guo, D. (2017). Asymmetric price adjustments: a supply side approach. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 50, 335–360.

Auer, Ρ, & Schonle, P. (2016). Market structure and exchange rate pass-through. Journal of International Economics, 98, 60–77.

Bacon, R. W. (1991). Rockets and feathers: the asymmetric speed of adjustment of uk retail gasoline prices to cost changes. Energy Economics, 13, 211–218.

Baghestani, H. (2015). Predicting gasoline prices using michigan survey data. Energy Economics, 50, 27–32.

Bagnai, A., Alexander, C., & Ospina, M. (2018). Asymmetries, outliers and structural stability in the US gasoline market. Energy Economics, 69, 250–260.

Berument, M. H., Sahin, A., & Sahin, S. (2014). The relative effects of crude oil price and exchange rate on petroleum product prices: evidence from a set of Northern Mediterranean countries. Economic Modelling, 42, 243–249.

Bonnet, C., Dubois, P., Villas Boas, S. B., & Klapper, D. (2013). Empirical evidence on the role of nonlinear wholesale pricing and vertical restraints on cost pass-through. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95, 500–515.

Borenstein, S., Cameron, A. C., & Gilbert, R. (1997). Do gasoline prices respond asymmetrically to crude oil price changes? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 305–339.

Byrne, D. P., & de Roos, N. (2017). Consumer search in retail gasoline markets. Journal of Industrial Economics, 65, 183–193.

Cabral, M., Geruso, M., & Mahoney, N. (2018). Do larger health insurance subsidies benefit patients or producers? Evidence from medicare advantage. American Economic Review, 108, 2048–2087.

Campa, J. M., & Minguez, G. (2006). Differences in exchange rate pass-through in the euro area. European Economic Review, 50, 121–145.

Chen, Y., Huang, G., & Ma, L. (2017). Rockets and feathers: the asymmetric effect between china’s refined oil prices and international crude oil prices. Sustainability MDPI Open Access Journal, 9(3), 1–19.

Chou, K. W., & Tseng, Y. H. (2016). Oil prices, exchange rate, and the price asymmetry in the taiwanese retail gasoline market. Economic Modelling, 52, 733–741.

Clerides, S. (2010). Retail fuel price response to oil price shocks in EU countries. Cyprus Economic Policy Review, 4, 25–45.

Coibion, O., & Gorodnichenko, Y. (2015). Is the phillips curve alive and well after all? Inflation expectations and the missing disinflation. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(1), 197–232.

Deltas, G. (2008). Retail gasoline price dynamics and local market power. Journal of Industrial Economics, 61, 613–628.

Deltas, G., & Polemis, M. (2020). Estimating retail gasoline price dynamics: the effects of sample characteristics and research design. Energy Economics, 92, 104976.

Faber, R. P., & Janssen, M. C. W. (2019). On the effects of suggested prices in gasoline markets. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 121, 676–705.

Feenstra, R. C. (1989). Symmetric pass-through of tariffs and exchange rates under imperfect competition: an empirical test. Journal of International Economics, 27, 25–45.

Galeotti, M., Lanza, A., & Manera, M. (2003). Rockets and feathers revisited: an international comparison on european gasoline markets. Energy Economics, 25, 175–190.

Gautier, E., & Le Saout, R. (2015). The dynamics of gasoline prices: evidence from daily french micro data. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 47, 1063–1089.

Genakos, C., & Pagliero, M. (2022). Competition and pass-through: evidence from isolated markets. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14(4), 35–57.

Goldberg, P. K., & Hellerstein, R. (2013). A structural approach to identifying the sources of local currency price stability. Review of Economic Studies, 80, 175–210.

Goldberg, P., & Knetter, M. (1997). Goods prices and exchange rates: what have we learned? Journal of Economic Literature, 35, 1243–1272.

Hahn, E. (2003). Pass-Through of External Shocks to Euro Area Inflation. ECB Working Paper Series, No. 243

Haliloglu, E. Y., & Berument, M. H. (2021). The asymmetric effects of crude oil prices and exchange rates on diesel prices for 27 European countries. Global Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150921999035

Helpman, E., & Krugman, P. (1987). Market Structure and Foreign Trade: Increasing Returns, Imperfect Competition, and the International Economy. The MIT Press.

Hurtado, C. (2019). Behavioral responses to spatial tax notches in the retail gasoline market. Manuscript. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3469900

Karagiannis, S., Panagopoulos, Y., & Vlamis, P. (2015). Are unleaded gasoline and diesel price adjustments symmetric? A Comparison of the Four Largest EU Retail Fuel Markets, Economic Modelling, 48, 281–291.

Karrenbrock, J. D. (1991). The behavior of retail gasoline: symmetric or not? Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review, 73, 19–29.

Kaufmann, R. K. (2019). Pass-through of motor gasoline taxes: efficiency and efficacy of environmental taxes. Energy Policy, 125, 207–217.

Kilian, L. (2008). A comparison of the effects of exogenous oil supply shocks on output and inflation in the G7 countries. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6, 78–121.

Kpodar, K., & Imam, P. A. (2021). To pass (or not to pass) through international fuel price changes to domestic fuel prices in developing countries: what are the drivers? Energy Policy, 149, 111999.

Kristoufek, L., & Lunackova, P. (2015). Rockets and feathers meet joseph: reinvestigating the oil-gasoline asymmetry on the international markets. Energy Economics, 49, 1–8.

Krugman, P. (1986). Pricing to Market when the Exchange Rate Changes. NBER Working Paper no. 1926

Lamotte, O., Porcher, T., Schalck, C., & Silvestre, S. (2013). Asymmetric gasoline price responses in France. Applied Economics Letters, 20, 457–461.

Lewis, M. S. (2011). Asymmetric price adjustment and consumer search: an examination of retail gasoline market. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 20, 409–449.

Lewis, M. S., & Marvel, H. P. (2011). When do consumers search. Journal of Industrial Economics, 59, 457–483.

Mann, J. (2016). Rockets and feathers meet markup margins: applications to the oil and gasoline industry. Canadian Journal of Economics, 49, 772–788.

McCarthy, J. (2007). Pass-through of exchange rates and import prices to domestic inflation in some industrialized economies. Eastern Economic Journal, 33, 511–537.

Meyler, A. (2009). The pass through of oil prices into euro area consumer liquid fuel prices in an environment of high and volatile oil prices. Energy Economics, 31, 867–881.

Miller, N. H., Osborne, M., & Sheu, G. (2017). Pass-through in a concentrated industry: empirical evidence and regulatory implications. RAND Journal of Economics, 48, 69–93.

Miravete, E. J., Seim, K., & Thurk, J. (2018). Market power and the laffer curve. Econometrica, 86, 1651–1687.

Nakamura, Ε, & Zerom, D. (2010). Accounting for incomplete pass-through. Review of Economic Studies, 77, 1192–1230.

Ogbuabor, J. E., Eigbiremolen, G. O., Manasseh, C. O., & Mba, I. C. (2018). Asymmetric price transmission and rent-seeking in road fuel markets: a comparative study of south africa and selected Eurozone countries. African Development Review, 30, 278–290.

Perdiguero-Garcia, J. (2013). Symmetric or asymmetric oil prices? A meta-analysis approach. Energy Policy, 57, 389–397.

Pesaran, M. H., & Smith, R. (1995). Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 79–113.

Polemis, M. (2012). Competition and price asymmetries in the greek oil sector: an empirical analysis on gasoline market. Empirical Economics, 43, 789–817.

Remer, M. (2015). An empirical investigation of the determinants of asymmetric pricing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 42, 46–56.

Tappata, M. (2009). Rockets and feathers: understanding asymmetric pricing. RAND Journal of Economics, 40, 673–687.

Venditti, F. (2013). From oil to consumer energy prices: how much asymmetry along the way? Energy Economics, 40, 468–473.

Weyl, E. G., & Fabinger, M. (2013). Pass-through as an economic tool: principles of incidence under imperfect competition. Journal of Political Economy, 121, 528–583.

Yanagisawa, A. (2012). structure for pass-through of oil price to gasoline price in Japan – effect of depreciation of the yen on the rise of gasoline price. IEEJ Energy Journal, 7(3), 55–67.

Yang, J. (1997). Exchange rate pass-through in U.S. manufacturing industries. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 79, 95–104.

Acknowledgements

We would like thank Lawrence White and two anonymous referees for helpful comments that have greatly improved the manuscript. We would also like to thank Katherine Cuff for useful detailed feedback, Michael Fotiadis for providing us with the Platts price quotations, and the organizers and participants of the 1st IAEE online conference, held in Paris from 7th–9th June 2021 for constructive suggestions on an earlier version of the paper. Partial support from the University of Piraeus Research Center is acknowledged. All data used in producing the results of the paper are available by the authors in a weekly frequency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Deltas, G., Polemis, M. Price Pass-Through Dependence on the Source of Cost Increases: Evidence from the European Gasoline Market. Rev Ind Organ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-024-09954-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-024-09954-0