Abstract

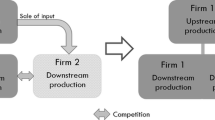

This paper extends Williamson’s (1968, 58(1):p. 18–36) classic framework of the welfare effect of mergers to the case of vertical mergers, and in particular to those in which the imposition of merger conditions (remedies) may allow an otherwise anticompetitive merger to proceed. While similarities to the case of horizontal mergers without a remedies option are present, differences also arise. Most notably: For prototypical vertical mergers, remedies may yield post–merger economic welfare that is higher than pre–merger levels. This suggests that remedies that are directed toward vertical mergers hold the promise of a more beneficial approach than in the case of horizontal mergers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

U.S. Department of Justice & Federal Trade Commission, Vertical Merger Guidelines (2020), https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1290686/download.

In this spirit, former Acting Associate Attorney General William Baer has argued that “[g]etting remedies right is central to merger enforcement policy.” See Acting Associate Attorney General Bill Baer Delivers Remarks at American Antitrust Institute’s 17th Annual Conference (June 16, 2016) (hereinafter “Baer Speech”), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/acting-associate-attorney-general-bill-baer-delivers-remarks-american-antitrust-institute.

U.S. Department of Justice, Merger Remedies Manual (2020) (“2020 Remedies Manual”), https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1312416/download.

This perspective, which we follow here, adopts a focus on total economic welfare. For a rich discussion of the alternatives, see Farrell and Katz (2006).

The welfare effects that are associated with mergers that involve only anticompetitive elements are clearly negative, and the welfare effects of mergers that involve only efficiency gains are unambiguously positive. Williamson focuses on the subset of mergers in which there are both efficiency gains and anticompetitive effects.

Williamson’s analysis is couched in a context in which price increases are the manifestation of the enhanced market power that is created by a merger. The tradeoff that is identified by Williamson is, however, equally applicable to other consequences of market power—including reduced innovation or reduced quality.

As observed by Farrell (2004), “while there is a lot of economics literature on the effects of mergers, I am not aware of much on merger fixes and divestitures.” More recently Vasconcelos (2010, p. 760) notes, “Economic theory has … devoted very scarce attention to the study of the equilibrium impact of remedies to mergers”; and Osinski and Sandford (2020, p. 1) refer to the “sparse literature on merger remedies.

Indications of market power at the various vertical stages sufficient to trigger Agencies’ concerns are likely to parallel those in horizontal contexts: such as large pre-existing market shares, concentration and significant barriers to entry. For a discussion of these, see the U.S. Department of Justice & Federal Trade Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines, August 19, 2010, available at https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2010/08/19/hmg-2010.pdf.

While the VMGs indicate that vertical mergers will often result in such efficiencies, our example is not intended to indicate that these efficiencies will occur in every vertical merger. See Salop (2018) and Luco and Marshall (2020) for discussions of situations in which the elimination of double marginalization is attenuated. The VMGs indicate that “While it is incumbent upon the merging firms to provide substantiation for claims that they will benefit from the elimination of double marginalization, the Agencies may independently attempt to quantify its effect based on all available evidence …” (p. 12).

We set aside here the significant debate about the conditions that may make such a strategy desirable and feasible for the vertically integrated firm; instead, we simply assume that such conditions do hold in some circumstances.

Kaserman and Mayo (1991) provide both the conceptual methodology for quantifying vertical economies and an example of an empirical application.

Parallel to the assumption in footnote 11, we set aside debates that arise with regard to the presence of both vertical economies and efficiency gains from the elimination of double marginalization with the plausible assumption that they do occur in some – though likely not all—vertical mergers.

Area A’ is the value of consumer surplus that is lost as a consequence of the merger, while D′ + Y′ represents the value of producer surplus that is lost as a consequence of the merger.

For an application of the quantification of such tradeoffs in the context of a horizontal merger, see Pittman (1990). Crawford et al. (2018) provide a quantitative assessment of the welfare effects outlined here for the case of multichannel television markets that vary in the degree to which they are vertically integrated.

See Salop (2013).

Litigation risk and cost assessments will be different for enforcers and the merging parties. Both must account for the direct costs of litigation and of remedies. The types of risks that they face in litigation are quite different, however: The merging parties primarily evaluate the financial impact from delay and potential deal failure, and the Agencies face a more complex set of policy and resource allocation issues. In addition, the Agencies arguably face higher litigation risks in vertical merger cases than in horizontal cases, given less advantageous legal standards—e.g., the absence of the Philadelphia National Bank presumption of harm from increased concentration—and the dearth of successful court challenges to vertical mergers in the past several decades.

Our example here introduces only litigation costs and remedy costs. If we were to admit litigation outcome uncertainty, the welfare analysis becomes more complicated but does not alter the conclusion that in the presence of litigation, administrative and enforcement costs remedy solutions may dominate pure litigation.

We assume here that β = A (in Fig. 1) so that the remedy completely eliminates the anticompetitive harm that is associated with the merger. In the event that β < A, the welfare analysis becomes more complicated but does not alter the conclusion that in the presence of litigation, administrative, and enforcement costs, remedy solutions may dominate litigation.

We assume here that a merger remedy can be identified and enforced (with cost δ) that eliminates the anticompetitive consequence of the as-proposed merger but that preserves the merger-induced efficiencies. In a horizontal merger, this is most likely to occur in mergers that involve multiple markets, only some of which raise competitive concerns. Divestiture remedies that eliminate the problematic overlap will also eliminate efficiencies (such as scale economies) in the overlap area, but they allow the rest of the merger to proceed and any resulting efficiencies to be realized. In practice, remedies may imperfectly accomplish this goal, and with varying cost. We allow for this likelihood in the discussion of the policies and practices of remedies in Section 3 below. Moreover, we assume that while remedies eliminate the ability of the firm to raise prices from P0–P1, the post-remedy price will depend on the cost pass-through rate that is associated with the merger-specific efficiencies. These may reasonably be bounded by a return to the pre-merger equilibrium price—P0 (no cost-pass-through—or a price that reflects the post-merger cost efficiencies: C1 (complete cost-pass-through). For an extensive survey of the cost-pass-through literature, see RBB Economics (2014).

A successful challenge will also result in the transfer of (X′) from producer surplus to consumer surplus.

The remedy will also result in the transfer of (X′ + C′) from producer surplus to consumer surplus.

As was noted in footnote 20, horizontal mergers can also create economies that—like vertical economies—may incentivize the merged firm to reduce prices due to cost-pass-through. In theory, remedies in horizontal merger cases could facilitate such efficiencies while eliminating anticompetitive price increases. However, the gains from the elimination of double marginalization is unique to vertical mergers.

This conclusion may evoke the literature on “over-fixing”, which Farrell (2004) describes as occurring when antitrust authorities demand a “more competitive outcome after the merger-plus-remedy than prevailed before.” Vergé (2010, p. 724) describes over-fixing as a policy in which the remedy results in “the price below its-pre-merger level”. While our result would nominally seem to be consistent with both of these descriptions, the principal discussion of and criticisms about over-fixing are directed to as-proposed mergers that have some market power-enhancing elements but that are, on net, welfare-enhancing and in which antitrust agencies nonetheless pursue remedies from the merging firms. In contrast, our analysis is specifically directed to welfare-reducing as-proposed mergers.

A broader way to frame these questions is to ask whether maximizing welfare in the design of vertical merger remedies would require that the agencies expressly adopt a total welfare standard for antitrust enforcement, rather than the “consumer welfare” standard that is often said to underpin U.S. antitrust enforcement. See, e.g.,Christine S. Wilson, Commissioner, Federal Trade Commission, Welfare Standards Underlying Antitrust Enforcement: What You Measure is What You Get (Feb. 15, 2019), Keynote Address at George Mason Law Review 22nd Annual Antitrust Symposium, available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1455663/welfare_standard_speech_-_cmr-wilson.pdf. As described below, however, as a practical matter the agencies have fashioned merger remedies policies that enable them to address potential harm to consumers while maximizing overall efficiencies, particularly for vertical mergers, without the need to redefine the welfare standards that generally guide their work.

See 2004 DOJ Policy Guide, at 4, quoting United States v. E.I. Du Pont de Nemours & Co., 366 U.S. 316, 326 (1961). Perhaps reflecting a generally somewhat more flexible approach to merger remedies, DOJ’s (since rescinded) 2011 Policy Guide placed less emphasis on fully restoring premerger levels of competition, referring instead at several points to the need to ensure that remedies “effectively preserve competition” (emphasis added). DOJ’s 2020 Merger Remedies Manual provides that remedies should “effectively redress the violation and, just as importantly, be no more intrusive than necessary to cure the competitive harm,” while also stating that a stand-alone conduct remedy will only be appropriate in lieu of a structural remedy if it “will completely cure” the harm. 2020 Remedies Manual, n.3 supra, Sections 2, 3.2 (2).

As an illustration, consider a merger between input supplier A and downstream manufacturer B, where A has a monopoly in the market for input 1, but also supplies inputs 2 and 3 for which A faces significant competition. An injunction that prohibits the entire transaction would address competitive concerns in the market for input 1, but could also eliminate efficiencies in the markets for inputs 1, 2, and 3. A divestiture remedy that is limited to input 1 would avoid competitive concerns in the input 1 market, but would eliminate efficiencies in that market, while potentially preserving efficiencies in the markets for inputs 2 and 3. A remedy that is narrowly designed to prevent the anticompetitive conduct of concern in the input 1 market without requiring any divestitures could potentially preserve efficiencies in all three input markets.

See, e.g., U.S. v. Philadelphia Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 371 (1963) (a merger that harms competition in one market “is not saved because, on some ultimate reckoning of social or economic debits and credits, it may be deemed beneficial”).

HMGs, Sec. 10.

VMGs, Sec. 6.

Horizontal Merger Guidelines issued by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) 13, 104, April 8, 1997.

HMGs, Sec. 10 n.14.

VMGs, Sec, 6 n.6.

See the Hart-Scott-Rodino Annual Reports, 2005–2018, which provide a comprehensive report of merger enforcement actions, as well as identifying cases that were fully litigated. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/policy/reports/policy-reports/annual-competition-reports.

See Baer Speech, n.2 supra (comparing remedies approaches in various cases, including proposals that DOJ deemed inadequate in Halliburton/Baker Hughes).

U.S. Department of Justice (2004) (hereinafter the “2004 Guide”).

U.S. Department of Justice (2011) (hereinafter the “2011 Guide”).

See, “Effective remedies preserve efficiencies created by a merger, to the extent possible, without compromising the benefits that result from maintaining competitive markets”. “ (2004 Guide, p. 4) and “Effective remedies preserve the efficiencies created by a merger, to the extent possible, without compromising the benefits that result from maintaining competitive markets.” (2011 Guide, p. 4.).

Makan Delrahim, Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division, U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust and Deregulation: Remarks Before the American Bar Association Antitrust Section Fall Forum (Nov. 16, 2017) (hereinafter “Delrahim Fall Forum Speech”), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-makan-delrahim-delivers-keynote-address-american-bar.

Makan Delrahim, Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division, U.S. Department of Justice, It Takes Two: Modernizing the Merger Review Process, Remarks as Prepared for the 2018 Global Antitrust Enforcement Symposium (Sept. 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/file/1096326/download

U.S. v. AT&T Inc., 916 F.3d 1029, (D.C. Cir. 2019).

2020 Remedies Manual, n.3 supra, Section II.

Id., Sections 3.2, 3.2(2).

Id., Section 3.2(2).

Ibid.

Statement of the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Competition on Negotiating Merger Remedies (2012) at 5 (“FTC Remedies Statement”), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/attachments/negotiating-merger-remedies/mergerremediesstmt.pdf.

D. Bruce Hoffman, Director, Bureau of Competition, Federal Trade Commission, Vertical Merger Enforcement at the FTC, Remarks Before the Credit Suisse 2018 Washington Perspectives Conference (Jan. 10, 2018) (hereinafter “Hoffman Speech”) at 3, 8.

See U.S. Department of Justice (2011). The line between conduct and structural remedies is in some instances blurred and more a question of semantics than of substance. At the extremes, a clean divestiture of a business is readily understood to be a structural remedy, while a requirement to behave in a certain way (such as "don't discriminate among customers") to be a conduct remedy. But many remedies that fall at the margin or do not neatly fit the definitions. For example, a requirement that a party exit a joint venture with another party would most accurately be described as structural, since, like a divestiture, it changes the legal ownership of assets. But what if the joint venture consists of a set of contracts, and the remedy requires a party to exit the contracts? This might be viewed as either structural or “conduct”: Similar to a divestiture, it changes the legal relationships that align certain firms with each other; yet it begins more closely to resemble “conduct” remedies such as those that require a party to change or abandon other contractual provisions.

A closer examination of the underlying cases in the Salop and Culley compendium suggests that Wong-Ervin’s summary may actually understate the Agencies’ relative reliance on conduct remedies for vertical concerns. As the ABA Antitrust Section noted in its comments on the proposed Vertical Merger Guidelines (Available at https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/antitrust_law/comments/february-2020/comment-22,420-ftc-doj.pdf), many of these cases also involved horizontal concerns, so that there were “at most” 58 vertical cases during the surveyed timeframe. (p. 3). Moreover, in some of those cases the same divestitures appear to have addressed both the horizontal and vertical issues, which suggests that the vertical concerns may not have meaningfully added to the remedy. See, e.g., CRH/Pounding Mill (DOJ, 2018); Premdor/Masonite (DOJ, 2001). In addition, in several cases that involved divestitures, the purported vertical theory of harm appears to be more accurately described as horizontal in nature. See, e.g., Danone/WhiteWave (DOJ, 2017); Nielsen/Arbitron (FTC, 2014); Premdor/Masonite (DOJ, 2001); SBC/Ameritech (DOJ, 1999). Salop and Culley’s updated compendium in April 2020 added several new cases between 2018–2020 that involved vertical theories, which brought the total number of such cases from 1994–2020 to (at most) 66. Of these, several were primarily horizontal cases, see, e.g., T- Mobile/Sprint (DOJ 2019), Sabre/Farelogix (DOJ, 2019), UnitedHealth/DaVita (FTC, 2019), and UTC/Rockwell Collins (DOJ 2018). Others involved no DOJ or FTC remedies, see Steves/Jeld-Wen (private litigation). Two cases resulted in Agency remedies that addressed primarily vertical concerns: one FTC case that involved conduct remedies (Staples-Essendant) and a DOJ case that employed a structural remedy (UTC-Raytheon). These two cases are discussed in greater detail below.

Note that other antitrust analysts have expressed skepticism with the policy implications of this result. See, e.g., Moss (2018, p. 10) who argues that “Divestiture to incumbents in the market would essentially be a game of ‘musical chairs,’ or shifting assets form one market incumbent to another.” While the Agencies do in some cases approve divestitures to firms that have existing capabilities in the relevant market, both agencies have stated that while a divestiture to a “fringe” competitor might be allowed, they will not approve divestitures to large or significant competitors. See DOJ 2004 Guide at 30; 2011 Guide at 28; FTC Remedies Statement at 11.

FTC (1999), p. 8.

See DOJ (2004), Kwoka and Moss (2012), and Delrahim Fall Forum Speech, note 38, supra.

We return to this point below in the detailed consideration of the AT&T/Time Warner merger.

See Memorandum Opinion, United States District Court for the District of Columbia, U.S.

v. AT&T Inc., et al., p. 67.

See Juan A. Arteaga, Enforcement of Merger Consent Decrees, Global Competition Review Merger Remedies (Second Edition 2019), https://globalcompetitionreview.com/insight/merger-remedies-guide-secondedition/1209559/enforcement-of-merger-consent-decrees.

There have been relatively few enforcement actions for merger decree violations, and most have involved decrees in horizontal mergers—often related to divestiture requirements. See generally Arteaga, n.58 supra. A notable exception, however, was the 2019 DOJ action that modified the consent decree in United States v. Ticketmaster Entertainment, Inc., which the DOJ described as its “most significant enforcement action of an existing antitrust decree by the Department in 20 years.” The DOJ alleged that Ticketmaster and Live Nation had repeatedly violated provisions of the decree that related to their 2010 merger by conditioning Live Nation’s provision of live concerts on venues’ purchase of Ticketmaster ticketing services. To address these concerns the modified decree imposed a number of new provisions, including: expanding the original decree’s conduct restrictions; extending the decree’s term by 5½ years; requiring the appointment of a monitoring trustee and compliance officer; and creating lower standards of proof and liquidated penalties for future violations. See https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-will-move-significantly-modify-and-extend-consent-decree.

See Delrahim Fall Forum speech, n. 38 supra.

2020 Remedies Manual, n. 3 supra, Section II (“[c]onduct remedies substitute central decision making for the free market”).

See n. 52, supra.

See cases discussed in n. 52, supra.

See, e.g., Staples/Essendant (FTC 2019), Broadcom/Brocade (FTC 2017), AMC/Carmike (DOJ 2016), GrafTech/Seadrift (DOJ 2011), Coke/Dr. Pepper (FTC 2010), Boeing/Lockheed Martin (FTC 2007), Boeing/GM (FTC 2000), Merck/Medco (FTC 1999), Boeing/Rockwell (FTC 1997), Lockheed Martin/Loral (FTC 1996), Raytheon/Chrysler (FTC 1996), Hughes Danbury/Itek (FTC 1996), Alliant/Hercules (FTC 1995), Sprint/France Telecom (DOJ 1995), Eli Lilly/McKesson (FTC 1995), Lockheed/Martin Marietta (FTC 1995), Martin Marietta/General Dynamics (FTC 1994), AT&T/McCaw (DOJ 1994), BT/MCI (DOJ 1994).

For examples of vertical foreclosure or raising rivals’ costs concerns’ being addressed by conduct provisions, see , e.g., Northrop Grumman/Orbital (FTC 2018), AB/InBev (DOJ 2016), Comcast/NBCU (DOJ 2011), GE/Avio (FTC 2011), Google/ITA DOJ 2011), Ticketmaster/Live Nation (DOJ 2010), Boeing/Lockheed Martin (FTC 2007), Northrop Grumman/TRW (DOJ 2003), Ceridian/Trendar (FTC 2000), AOL/Time Warner (FTC 2000), Boeing/GM (FTC 2000), Provident/UNUM (FTC 2000), Merck/Medco (FTC 1999), CMS/Duke (FTC 1999), Shell/Texaco (FTC 1998), Cadence/Cooper & Chryan (FTC 1997), Time Warner/Turner (FTC 1997), Boeing/Rockwell (FTC 1997), Lockheed Martin/Loral (FTC 1996), Hughes Danbury/Itek (FTC 1996), Silicon Graphics/Alias (FTC 1995), Sprint/France Telecom (DOJ 1995), Eli Lilly/McKesson (FTC 1995), Lockheed/Martin Marietta (FTC 1995), AT&T/McCaw (DOJ 1994), BT/MCI (DOJ 1994), TCI/Liberty (DOJ 1994).

See , e.g., UTC/Raytheon (DOJ 2020), Bayer/Monsanto (DOJ 2018), UTC/Goodrich (DOJ 2012).

U.S. v. AT&T Inc., 310 F. Supp 3d 161 (D.D.C. 2018).

U.S. v. AT&T Inc., 916 F.3d 1029, (D.C. Cir. 2019).

Id. at 32. (emphasis in original).

In Re Sycamore Partners II, L.P., Staples, Inc. and Essendant Inc., No. C-4667 (FTC Jan. 25, 2019), available at https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/cases-proceedings/181-0180/sycamore-partners-ii-lp-staples-inc-essendant-inc-matter.

U.S. v. United Technologies Corp. and Raytheon Company, No. 1:20-cv-00824 (D.D.C. 2020), available at https://www.justice.gov/atr/case/us-v-utc-and-raytheon

See the cases that were cited in n. 64 and n. 65, supra.

Vertical Merger Guidelines, Sec. 4-a.

References

Cabral, L. (2003). Horizontal mergers with free-entry: why cost efficiencies may be a weak defense and asset sales a poor remedy. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21(5), 607–623.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

Crawford, G. S., Lee, R. S., Whinston, M. D., & Yurukoglu, A. (2018). The welfare effects of vertical integration in multichannel television markets. Econometrica, 86(3), 891–954.

Dertwinkel-Kalt, M., & Wey, C. (2016). Merger remedies in oligopoly under a consumer welfare standard. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 32(1), 150–179.

Farrell, J. (2004) Negotiation and merger remedies: some problems, in Merger Remedies in American and European Union Competition Law, Francois Leveque and Howard Shelanski, eds., Edward Elgar.

Farrell, J., Katz, M. L., (2006). The economics of welfare standards in antitrust. Competition Policy International, 2(2).

Federal Trade Commission (FTC). (2017). The FTC’s Merger Remedies 2006–2012: A Report of the Bureaus of Competition and Economics. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/ftcs-merger-remedies-2006-2012-report- bureaus-competition-economics/p143100_ftc_merger_remedies_2006–2012.pdf.

Federal Trade Commission (FTC), A study of the commission’s divestiture process, bureau of competition, August 1999. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/study-commissions- divestiture-process.

Friberg, R., & Romahn, A. (2015). Divestiture requirements as a tool for competition policy: a case from the swedish beer market. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 42(September), 1–18.

Johansen, B. O. & T. Nilssen (2019) Merger remedies, incomplete information, and commitment. working paper. Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/79d4/e29f3624ea82f080a3213c295320492e6374.pdf.

Kaserman, D. L., & Mayo, J. W. (1991). The measurement of vertical economies and the efficient structure of the electric utility industry. Journal of Industrial Economics, 39(5), 483–502.

Kwoka, J. E., & Moss, D. L. (2012). Behavioral merger remedies: evaluation and implications for antitrust enforcement. Antitrust Bulletin, 57(4), 979–1011.

Luco, F., & Marshall, G. (2020). The competitive impact of vertical integration by multiproduct firms. American Economic Review, 110(7), 2041–2064.

Moss, D.l. (2018). Realigning merger remedies with the goals of antitrust. American Antitrust Institute.

Motta, M., Polo, M., & Vasconcelos, H. (2007). Merger remedies in the european union: an overview. Antitrust Bulletin, 52(3–4), 603–631.

Osinski, F. D., Sandford. J. A. (2020). Evaluating Mergers and Divestiture,”: A Casino Case Study. Working paper. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3008770.

Pittman, R. (1990). Railroads and competition: the santa fe/southern pacific merger proposal. Journal of Industrial Economics, 39(1), 25–46.

RBB Economics (2014) Cost pass-through: theory, measurement and potential policy implications. Aa report prepared for the Office of Fair Trading, London.

Salop, S. C. (2013). Merger Settlement and Enforcement Policy for Optimal Deterrence and Maximum Welfare. Fordham Law Review, 81(5), 2647–2681.

Salop, Stephen C. “Invigorating Vertical Merger Enforcement,” Yale Law Journal, Vol. 127, May 2018, pp. 1962–1994.

Salop, S. C. & D. P. Culley. (2015). Vertical Merger Enforcement Actions: 1994-April 2020. Georgetown University Law Center.

Tenn, S., & Yun, J. M. (2011). The success of divestitures in merger enforcement: evidence from the J&J-Pfizer transaction. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 29, 273–282.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2004). Antitrust Division Policy Guide to Merger Remedies. Antitrust Division, October 2004. Available at https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1175136/download.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2011). Antitrust Division Policy Guide to Merger Remedies. Available at https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2011/06/17/272350.pdf.

Vasconcelos, H. (2010). Efficiency gains and structural remedies in merger control. Journal of Industrial Economics, 58(4), 742–766.

Vergé, T. (2010). Horizontal mergers, structural remedies and consumer welfare in a cournot oligopoly with assets. Journal of Industrial Economics, 58(4), 723–741.

Williamson, O. (1968). Economies as an antitrust defense: the welfare tradeoffs. American Economic Review, 58(1), 18–36.

Wong-Ervin, K. W., (2019) Antitrust Analysis of Vertical Mergers: Recent Developments and Economic Teachings. The Antitrust Source, 1–13.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Roger Blair, Tim Brennan, Nathan Miller, Russell Pittman, Thomas Ross, Daniel Sokol and Koren Wong-Ervin for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We also appreciate the helpful suggestion and comments of the editor, Lawrence J. White.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mayo, J.W., Whitener, M. The Welfare Effects of Vertical Mergers and their Remedies. Rev Ind Organ 59, 409–441 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-021-09829-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-021-09829-8