Abstract

We examine the extent of market power in the brewing market of Perú, where the absence of preventive merger review eased consolidation into a single industrial brewer. We use a standard oligopoly model and exploit both seasonality in demand and atypically large and frequent variations in the structure and level of excise taxes to identify variations in market power. Our results provide evidence of the ineffectiveness of competition policy as uncontested mergers resulted in a degree of market power that decreased only with the entry of new firms.

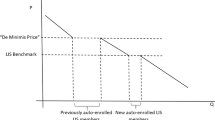

Source: Own elaboration based on Perú’s National Institute of Statistics (INEI)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The enforcement of merger policies differs among countries, most probably because differences in national size tend to condition the choice of welfare standards. See OECD (2014).

Shleifer and Vishny (1991) favor a lax merger enforcement standard because, while leniency may lead to monopoly, tough enforcement could lead to an industry structure that is dominated by conglomerates.

For example, Australia’s and Canada’s merger regimes include a specific instruction that a significant increase in the real value of exports should be considered to be an efficiency gain (Gal 2009).

An opposing argument to the post-hoc approach states that ex-ante regulation is usually cheaper because ex-post remedies are not always practical or economically viable. This view also claims that a lax antitrust policy eases concentration, which then facilitates influence and rent-seeking.

AJE exited the market in 2013. In 2015, the global merger between ABInBev and SabMiller again concentrated the Peruvian market into a single brewer.

We cannot determine if the anticompetitive conduct originates in the nonexistence of preventive reviews, or in the quality of post-hoc enforcement.

Industry concentration into few brewers has raised debate worldwide. See for example Davison, A. “Are we in danger of a beer monopoly?” February 26, 2013, The New York Times Magazine; and The Economist “Brewer monster”, September 15, 2015.

The leniency of Peru’s competition policy approach has been a point of debate, and the policy remains on the legislative agenda. See Semana Económica “La resaca de la fusión”, October 18, 2015.

Perú does not have a competition agency per se. INDECOPI’s competition policy issues are carried out by the Free Competition Chamber—which oversees matters on antitrust, consumer protection, and bureaucratic barriers to entry—and the Intellectual Property Chamber—which addresses patent, copyright, and trademark issues.

In Colombia, where merger reviews were not enforced until 2009, industry concentration was also close to monopoly (HHI = 9851). Where preventive reviews exist, concentration is much lower (HHI for Argentina, Brazil and Chile of 5953, 4518 and 5773, respectively; see Krauss 2009; Toro-Gonzalez 2015). We thank a reviewer for raising this point.

In 1910, CNC’s Pilsen was the market leader. Backus introduced the Cristal brand in 1922.

The low level of imports is striking. In our study period, Peruvian beer import duties were slightly lower than those of other Latin American markets, where beer imports were higher (see http://tariffdata.wto.org/). In our view, imports (by a non-brewer incumbent) may be undermined by the high costs of establishing a distribution network—see reference to vertical integration below.

Beer is generally treated as a fairly well-differentiated product (Rojas and Peterson 2008; Eckert and West 2013). However, South American countries are not specifically recognized for their brewing traditions; brand differentiation in terms of style and taste is modest, and the craft beer market is incipient and still small (Toro-Gonzalez 2015). Our treating of beer as a relatively homogeneous product is reasonable.

See Perloff et al. (2007) for a detailed account of the model and interpretations of \(\lambda\).

These works compare conduct as measured directly by the elasticity-adjusted Lerner index with that measured indirectly using NEIO techniques. They validate the NEIO approach, although Kim and Knittel (2006) offer counter-evidence.

To our best knowledge, wholesale price data at the product level in Peru is available only since 1995 (see http://iinei.inei.gob.pe/iinei/siemweb/publico/.), which places an initial bound on our initial study period. The rapid proliferation of new brands that began in 2007 (they increased from 11 to 23 in only 4 years), jointly with the lack of brand-level price data, led us end our study period in that year.

Between 1995 and 2007 (our study period), the average annual inflation rate was 4.55% (the highest was 11.1% in 1995, and the lowest was 0.2% in 2002). Source: www.worldbank.org.

We used census data for total population over 20 years of age.

Lima accounts for more than two-fifths of Peru’s population.

We tested for seasonality in our temperature series using the unobserved component methodology. We were able to reject the null hypothesis of no seasonality (\(\chi ^2=463.43\); p value = 0.000). The pattern is persistent in the sample period, with peak months in January, February, and March.

The standard notation for Peruvian soles is S./. To ease reading, we refer to soles as S and denote US dollars as US$. In our study period, 1 US$ = S2.70, on average. The tariff on agricultural imports was 6%.

This follows our concern with any potential oligopsony power that was exercised by brewers in this market.

As stated by Greene (2012), finding the starting values for a nonlinear procedure can be difficult and, unfortunately, there are no good rules for starting values. In our case, the natural set of starting values comes from the initial demand estimates.

Results with quarterly data were identical. For brevity, we report results for monthly data only.

We also used other variables to examine the potential effect of economic activity on demand, but results proved non-significant.

Henceforth, parameters’ averages weight each estimate by the inverse of its standard error.

The over-identifying restrictions test is often interpreted as a test of validity of the instruments.

Our estimates of per liter marginal costs are similar to those in Tremblay and Tremblay (2005).

The monopolist did not price at the monopoly level. This can be related to the potential threat of post-merger investigation (and any potential reputational effect associated with it; Shaffer and DiSalvo 1994). In addition, monopoly pricing could have prompted quicker entry, a process that was well underway in other South American countries. Therefore, industry concentration was perhaps not aimed at exercising (pricing) market power but to raise entry barriers—recall our discussion at the end of Sect. 2 and how these measures delayed entry.

We thank the editor for raising this point.

To save space, these results are available upon request

Of course, this position assumes that ex-ante structural assessment is more effective than ex-post evaluation of conduct.

Even though Vartia’s algorithm appears to be more accurate, we use both methodologies as means of comparison (Sun and Xie 2013).

References

Appelbaum, E. (1979). Testing price taking behaviour. Journal of Econometrics, 9(3), 283–294.

Ashenfelter, O. C., Hosken, D. S., & Weinberg, M. C. (2015). Efficiencies brewed: Pricing and consolidation in the US beer industry. The RAND Journal of Economics, 46(2), 328–361.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217.

Berndt, E. R., & Khaled, M. S. (1979). Parametric productivity measurement and choice among flexible functional forms. The Journal of Political Economy, 87(6), 1220–1245.

Breslaw, J. A., & Smith, J. B. (1995). A simple and efficient method for estimating the magnitude and precision of welfare changes. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 10(3), 313–327.

Buschena, D. E., & Perloff, J. M. (1991). The creation of dominant firm market power in the coconut oil export market. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 73(4), 1000–1008.

Clay, K., & Troesken, W. (2003). Further tests of static oligopoly models: Whiskey, 1882–1898. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 51(2), 151–166.

Cooter, R. D. (1996). The theory of market modernization of law. International Review of Law and Economics, 16(2), 141–172.

De Loecker, J., & Scott, P. T. (2016). Estimating market power evidence from the US Brewing Industry (No. w22957). New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Denney, D., Lee, B., Noh, D. W., & Tremblay, V. (2002). Excise taxes and imperfect competition in the US brewing industry. Working Paper, Department of Economics, Oregon State University.

Eckert, A., & West, D. S. (2013). Proliferation of Brewers’ brands and price uniformity in Canadian beer markets. Review of Industrial Organization, 42(1), 63–83.

Farrell, J., & Shapiro, C. (1990). Horizontal mergers: An equilibrium analysis. The American Economic Review, 80(1), 107–126.

Fogarty, J. (2010). The demand for beer, wine and spirits: A survey of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 24(3), 428–478.

Gal, M. S. (2009). Competition policy for small market economies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Genesove, D., & Mullin, W. P. (1998). Testing static oligopoly models: Conduct and cost in the sugar industry, 1890–1914. The RAND Journal of Economics, 29(2), 355–377.

Godek, P. E. (1998). Chicago-school approach to antitrust for developing economies. The Antitrust Bulletin, 43(1), 261–274.

Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hansen, L. P. (1982). Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50(4), 1029–1054.

Hansen, L. P., & Singleton, K. J. (1982). Generalized instrumental variables estimation of nonlinear rational expectations models. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50(5), 1269–1286.

Hausman, J. A. (1981). Exact consumer’s surplus and deadweight loss. The American Economic Review, 71(4), 662–676.

Hausman, J. A., & Gregory, K. L. (2002). The competitive effects of a new product introduction: A case study. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 50(3), 237–263.

Hüschelrath, K. (2009). Detection of anticompetitive horizontal mergers. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 5(4), 683–721.

Hylton, K. N., & Deng, F. (2007). Antitrust around the world: An empirical analysis of the scope of competition laws and their effects. Antitrust Law Journal, 74(2), 271–341.

Irvine, I. J., & Sims, W. A. (1998). Measuring consumer surplus with unknown Hicksian demands. The American Economic Review, 88(1), 222–314.

Kim, D. W., & Knittel, C. R. (2006). Biases in static oligopoly models? Evidence from the California electricity market. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 54(4), 451–470.

Krauss, J. (2009). Merger policy in latin America. In E. Fox & D. Sokol (Eds.), Competition and law and policy in latin America (pp. 433–452). New York: Hart Publishing.

Kwoka, J. E, Jr. (2013). Does merger control work? A retrospective on US enforcement actions and merger outcomes. Antitrust Law Journal, 78(3), 619–650.

Malmquist, S. (1993). Index numbers and demand functions. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 4(3), 251–260.

Margaretic, P., Martinez, M. F., & Petrecolla, D. (2005). The effectiveness of antitrust enforcement in Argentina, Chile and Peru during the 90. publicaciones del Centro de Estudios Económicos de la Regulación, Working Paper, (16).

Mark Anderson, D., Hansen, B., & Rees, D. I. (2013). Medical marijuana laws, traffic fatalities, and alcohol consumption. The Journal of Law and Economics, 56(2), 333–369.

Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M. D., & Green, J. R. (1995). Microeconomic theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

McKenzie, G., & Pearce, I. (1976). Exact measures of welfare and the cost of living. Review of Economic Studies, 43(3), 465–468.

Mitchell, L. (2016). Demand for wine and alcoholic beverages in the EU: A monolithic market? Journal of Wine Economics, 11(3), 414–435.

OECD (2014). Investigations of consummated and non notifiable mergers, 14 DAF/COMP/WP 3/WD(2014)23, available at http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/WP3/WD%282014%2923&docLanguage=En

Ottaviani, M., & Wickelgren, A. L. (2011). Ex ante or ex post competition policy? A progress report. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 29(3), 356–359.

Parsons, C. R., & de Vanssay, X. (2014). Detecting market competition in the Japanese beer industry. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 14(1), 123–143.

Perloff, J. M., Karp, L. S., & Golan, A. (2007). Estimating market power and strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pinkse, J., & Slade, M. E. (2004). Mergers, brand competition, and the price of a pint. European Economic Review, 48(3), 617–643.

Reny, P. J., Wilkie, S. J., & Williams, M. A. (2012). Tax incidence under imperfect competition: Comment. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 30(5), 399–402.

Rojas, C. (2008). Price competition in US brewing. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 56(1), 1–31.

Rojas, C., & Peterson, E. B. (2008). Demand for differentiated products: Price and advertising evidence from the US beer market. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 26(1), 288–307.

Sass, T. R. (2005). The competitive effects of exclusive dealing: Evidence from the US beer industry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 23(3), 203–225.

Shaffer, S., & DiSalvo, J. (1994). Conduct in a banking duopoly. Journal of Banking and Finance, 18(6), 1063–1082.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1991). Takeovers in the’60s and the’80s: Evidence and Implications. Strategic Management Journal, 12(S2), 51–59.

Slade, M. (2004). Market power and joint dominance in the U.K. brewing. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 52(1), 133–163.

Spiller, P. T., & Favaro, E. (1984). The effects of entry regulation on oligopolistic interaction: The Uruguayan banking sector. The Rand Journal of Economics, 15(2), 244–254.

Sun, Z., & Xie, Y. (2013). Error analysis and comparison of two algorithms measuring compensated income. Computational Economics, 42(4), 433–452.

Toro-Gonzalez, D. (2015). The beer industry in latin America. Working Paper, American Association of Wine Economists.

Tremblay, C. H., & Tremblay, V. J. (1995). Advertising, price, and welfare: Evidence from the US brewing industry. Southern Economic Journal, 62(2), 367–381.

Tremblay, V. J., & Tremblay, C. (2005). The US brewing industry: Data and economic analysis. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Vartia, Y. O. (1983). Efficient methods of measuring welfare change and compensated income in terms of ordinary demand functions. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 51(1), 79–98.

Acknowledgements

Ariel A. Casarin: Financial support from IDRC-Canada Grant 107206-001 is gratefully acknowledged. We thank three anonymous reviewers and in particular the editor for his valuable suggestions and guidance in improving our paper. All errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Measurement of Welfare Changes

Appendix: Measurement of Welfare Changes

The consumer surplus that is calculated from the Marshallian demand function is not an exact measure of welfare change (Vartia 1983, p. 160). The computation of the compensating variation (CV) is based on the Hicksian demand function but, in practice, we can only retrieve information from the Marshallian demand function. Hausman (1981) derives the exact CV for some Marshallian demand specifications with a single price change. However, this method is difficult to implement if the demand function is complex and two or more price changes occur. An alternative is to approximate welfare measures with the use of one-step approximations, which are easy to implement but the precision of the estimates is lower than those of numerical alternatives (Sun and Xie 2013).Footnote 35

Consequently, we use the numerical approaches that are proposed by Vartia (1983) and Breslaw and Smith (1995).Footnote 36 Suppose that initial income is \(C^{0}\), the Marshallian demand is q(p, C), and the price changes from \(p^{0}\) to \(p^{1}\). Now divide the change in p into k small steps such that \(k=1,\ldots ,n\). Within each partitioned step from \(p_{k-1}\) to \(p_{k}\), Vartia’s (1983) algorithm first finds a converging ending point \(q(p_{k},C_{k})\) at ending price \(p_{k}\) and it then approximates the integral of the Hicksian demand as the trapezoidal area between the two prices formed by the initial and ending points. Therefore, the algorithm generates a sequence of \(C_{1} \ldots C_{n}\) so that:

where \(\Delta p_{k}=p_{k}-p_{k-1}\). At step n, the estimator \(C_{n}\) converges to the compensated income \(C^{1}\) as the number of partitioned steps n increases. The CV is then simply the difference between \(C^{1}\) and \(C^{0}\).

Breslaw and Smith (1995) apply a Taylor expansion into the expenditure function and use the Slutzky equation to approximate the integral of the Hicksian demand. If the price change \(p^{0}\) to \(p^{1}\) is also divided into k small steps, this algorithm generates a sequence of \(C_{1},\cdots , C_{n}\) so that:

where \(S(p,C)={(\partial q_{k-1}}/{\partial p)}+{(\partial q_{k-1}}/{\partial C)}\cdot q_{k-1}\) is the Slutzky equation. All the parameters can be obtained from an estimated Marshallian demand function. The estimator \(C_{n}\) converges to the compensated income \(C^{1}\) as the number of steps n increases and the CV is again the difference between \(C^{1}\) and \(C^{0}\).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Casarin, A.A., Cornejo, M. & Delfino, M.E. Market Power Absent Merger Review: Brewing in Perú. Rev Ind Organ 56, 535–556 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-019-09703-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-019-09703-8