Abstract

This paper examines how an individual’s labor supply responds immediately to her spouse’s health shock in an aging household and how she adjusts her labor supply over time after her spouse’s health shock. Different from previous work, this paper considers the subsequent health evolution following the spouse’s health shock by proposing an adaptation model where the long-term labor supply adjustment of an individual is allowed to depend on her spouse’s health evolution after the initial shock. Analysis of the 1996-2012 data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) suggests that in the short run, both husbands and wives change their labor supply very little when their spouses become ill, but in the long run, a husband’s labor supply adjustment does vary with his wife’s current health status after her initial health shock. In contrast, the wife’s annual work hours are not affected by her husband’s health shock in the long run, regardless of husband’s subsequent health status. Households with an ill wife are probably at greater risk than those with an unhealthy husband in the long run, which may be attributed to the role that women have traditionally played in the household.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since the sample in this study is composed of married couples and labor supply models will be estimated for husbands and wives separately, these individual fixed effects also capture all household fixed effects. An example of the household-specific time invariant unobserved heterogeneity is the similar lifestyle shared between spouses, while the individual-specific time invariant unobserved factor can be one’s self-discipline or time management.

Coile (2004) further reveals that the wife is more likely to exit the labor force if her husband’s health shock is severe.

This paper uses the RAND HRS data produced by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging.

The 1996–2012 waves of the HRS examined in this paper overlap with the time period investigated in the majority of cited work, making it especially meaningful to compare the new evidence found in this study with the results revealed in previous literature.

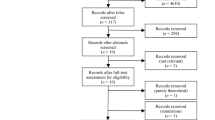

If either spouse in a household dies in a given wave, the current wave and subsequent observations for this household will be excluded from this sample. If one spouse reports herself being divorced in a given wave, the corresponding observation for this household in this wave is excluded.

Here “single” means a respondent remains single across all waves. In addition, households with a remarriage are excluded, since spousal health shocks probably cause a change in household composition that may independently influence an individual’s labor supply decision (Levy, 2002), which is beyond the scope of this study.

The sample excludes households with only one wave for the sake of a longitudinal data set.

As people age, there likely be a growing number of zero work hours observed in the sample if retirement is an absorbing state. Such a mass of observations with zero hours may cause biased estimates of the labor supply effects of bad health. To address it, I restrict the sample to those individuals who are not retired when they are first observed in the sample, and for them, I include the interview waves up to the first time they report their labor force status as retired. In other words, those observations after retirement will be excluded from the panel of study for these individuals, regardless of their subsequent employment status. I conduct such sample restrictions for males and females separately and then estimate the labor supply model in (1). The estimation results for the restricted sample (available upon request) are generally consistent with the main conclusions drawn for the full sample of this study. In addition, to control for potential joint retirement decision within a couple, I include an indicator of whether the spouse is retired as a covariate in one’s labor supply equation. This alternative specification yields qualitatively the same results as model (1).

The validity of the excluded variables is tested and discussed in Appendix C. The test results verify that the excluded objective health variables are highly correlated with self-assessed health measures and that the excluded variables do not directly affect the dependent variable in the structure model of interest.

The endogeneity tests presented in Table 1 reject the null hypothesis that own and spousal subjective health variables are exogenous in labor supply equations, which justify the implemented IV approach. The construction of optimal instruments through the probit model in (2) and the first-stage regression results are presented in Table A3 and Table A4 of Appendix A, respectively. See Appendix C for the discussion of the validity of constructed optimal instrumental variables.

As in basic model, I also conduct an alternative specification by including an indicator of whether the spouse is retired as a covariate in model (3). The alternative specification produces qualitatively the same results as the adaptation model presented in Equation (3).

The estimation results for the first-stage regressions of 2SLS are presented in Table A6 of Appendix A. The optimal instruments for health status and interactions are strongly correlated with the corresponding endogenous variables.

When analyzing the age range of 45–59, the estimated coefficient on \(D_{it}^s\) in the regression of wife’s work hours is −134.6 and significant at the 10% level if the current health is measured by work-limiting health conditions. However, the coefficient on \(D_{it}^s\) is not significant in analyses of other age ranges. Detailed regression results are available upon request.

For the age range of 45–63, the estimated coefficients on \(H_{it}^s \ast D_{it}^s\) in the models of husband’s work hours are negative and statistically significant, regardless of which measure of spouse’s current health is examined. It is noteworthy that the significant coefficient on this interaction when work-limiting health condition is examined differs from the insignificant estimation results for the 45–70 age range and does not remain significant for other age ranges. In addition, when analyzing the age ranges of 45–67 and 45–68, the estimated coefficients on \(H_{it}^s\) in the models of wife’s work hours are negative and statistically significant if self-reported health status is examined. However, the coefficient on \(H_{it}^s\) is not significant for other age ranges. Detailed regression results of these exceptions are available upon request.

References

Anand, P., Dague, L., & Wagner, K. L. (2022). The role of paid family leave in labor supply responses to a spouse’s disability or health shock. Journal of Health Economics, 83, 102621 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2022.102621.

Berger, M. C., & Fleisher, B. M. (1984). Husband’s health and wife’s labor supply. Journal of Health Economics, 3(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6296(84)90026-2.

Blau, D. M., & Gilleskie, D. B. (2001). The effect of health on employment transitions of older men. In Worker Wellbeing in a Changing Labor Market. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-9121(01)20037-5.

Bound, J. (1991). Self-reported versus objective measures of health in retirement models. The Journal of Human Resources, 26(1), 106–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/145718.

Braga, B., Butrica, B. A., Mudrazija, S., & Peters, H. E. (2022). Impacts of State Paid Family Leave Policies for Older Workers with Spouses or Parents in Poor Health. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4114537.

Charles, K. K. (1999). Sickness in the family: Health shocks and spousal labor supply. Ann Arbor, MI: Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, University of Michigan.

Coile, C. (2004). Health shocks and couples’ labor supply decisions. http://www.nber.org/papers/w10810.

Coile, C., Rossin-Slater, M., & Su, A. (2022). The Impact of Paid Family Leave on Families with Health Shocks.

Currie, J., & Madrian, B. C. (1999). Health, health insurance and the labor market. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 3309–3416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4463(99)30041-9.

Dobkin, C., Finkelstein, A., Kluender, R., & Notowidigdo, M. J. (2018). The economic consequences of hospital admissions. American Economic Review, 108(2), 308–352. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161038.

García-Gómez, P., Van Kippersluis, H., O’Donnell, O., & Van Doorslaer, E. (2013). Long-term and spillover effects of health shocks on employment and income. Journal of Human Resources, 48(4), 873–909. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2013.0031.

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2021). Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 254–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014.

Johnson, R. W., Mermin, G., & Uccello, C. E. (2005). When the nest egg cracks: Financial consequences of health problems, marital status changes, and job layoffs at older ages. Marital Status Changes, and Job Layoffs at Older Ages (December 2005).

Levy, H. (2002). The economic consequences of being uninsured. ERIU Working paper, 12. http://www.umich.edu/~eriu/pdf/wp12.pdf.

Newey, W. K. (1990). Efficient Instrumental Variables Estimation of Nonlinear Models. Econometrica, 58(4), 809–837. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938351.

Parsons, D. O. (1977). Health, Family Structure, and Labor Supply. The American Economic Review, 67(4), 703–712. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1813401.

Siegel, M. J. (2006). Measuring the effect of husband’s health on wife’s labor supply. Health Economics, 15(6), 579–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1084.

Stern, S. (1989). Measuring the effect of disability on labor force participation. The Journal of Human Resources, 24(3), 361–395. https://doi.org/10.2307/145819.

Van Houtven, C. H., & Coe, N. B. (2010). Spousal health shocks and the timing of the retirement decision in the face of forward-looking financial incentives. Working Papers, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College wp2010-6, Center for Retirement Research.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees for constructive comments and suggestions that have improved the paper considerably. I would also like to thank the participants at the Southern Economic Association (SEA) meeting 2020 in New Orleans, LA and the Southeastern Micro Labor Workshop 2022 in Columbia, SC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author confirms sole responsibility for study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, N. Health and household labor supply: instantaneous and adaptive behavior of an aging workforce. Rev Econ Household 21, 1359–1378 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09636-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09636-4