Abstract

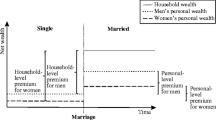

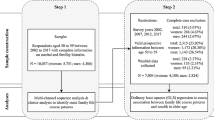

Wealth accumulation is the result of several factors: saving behaviors, inheritance, work and marital histories. In a context of increasing diversity of marital histories over cohorts, this article examines how relationship history may shape long-term wealth accumulation and wealth inequality. It goes beyond household wealth by looking at individual wealth. Focusing on individuals above 50 and using data from cross-sectional wealth surveys conducted in France in 2004, 2009, and 2014, we evaluate the contribution of their marital histories to individual wealth across different birth cohorts of men and women. We document the existence of a couple wealth premium, observed for both married and unmarried partners who are wealthier than the divorced, separated, or always single. Accumulated wealth significantly depends on marital history. Women have smaller wealth when they have not been continuously in a relationship. This is also the case for men but only for those belonging to the lowest quantiles. Over birth cohorts, marital break-up is responsible for less accumulated wealth. This is mainly noticeable for cohorts born after WWII. If marital histories had not diversified, the wealth accumulated by women would have been greater at older ages and those of men would have been more evenly distributed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since there is no agreement, and no possibility of contract, this regime involves de facto that each spouse retains exclusive ownership of property acquired during the marriage.

In a separate property regime, couples hold all their assets separately. For most married couples, the property regime is the community property, where all assets acquired during the marriage (except inheritances) is owned jointly by both spouses.

Computed as life expectancy measured at the age of effective labour market exit for men and women (see OECD, 2019).

Frémeaux and Leturcq (2022) very recently investigates property regimes as a determinant of differential wealth accumulation between couples. Those with a separate property regimes accumulate more than couples with a community property regime.

Laws of 11 July 1975 and 30 June 2000.

In some cases, savings accounts and life insurance were declared as jointly owned by the reference person and their spouse. In these cases, we consider the asset as jointly owned.

We define as equal sharing all couples for whom the difference between equal sharing of wealth and individual owned wealth is less than 10% in absolute values.

To test this equal split assumption, we consider couples in which at least one partner is between 50 and 75 years old, the age of the second member may be out this age range.

For the last two categories, the information about the past marital history is available at the household level. We thus only know that at least one of the two partners has been divorced in the past.

Note that the y-axis scales are not identical to make the graph as readable as possible.

Years of work are computed as the number of years in full-time-equivalent employment until the age of fifty to compare cohorts on the same lifespan. A year worked part-time is counted as a half-year and we exclude years of unemployment, in order to obtain a measure of real experience.

In France, upon the death of a spouse, the survivor may choose between inheriting at least 1/4 of the wealth of the dead spouse (in full ownership) or the right of usufruct (the right to use the property and receive the income) on his whole inheritance. The share of the inheritance in full ownership may even be higher if the couple signed a specific contract, which results in a higher part of inheritance for the survivor. Note that the surviving spouse’s share, while increased by this type of contract, remains limited. Under French law, children are always entitled to a part of the inheritance.

As always single have never been in a coresidential relationship, this duration is by definition zero. The coefficient of their dummy variable now compares them to very recently married individuals with a union duration of zero years, while in columns 1 & 3, they are compared to married individuals with the average union duration. This explains why the parameter of always single is not significant in columns 2 & 5.

We use two different specifications for individuals based on first results where all specifications were linear or quadratic. We ended with a quadratic form for individuals still in a relationship and a linear form for single individuals after a relationship. This is, at least for people still in a union, consistent with Lersch and Kappelle (2020), who found an increasing premium during the first years of marriage.

Moreover, we may expect the level of donations to be higher for married compared to others. Although we have some information on this aspect in the survey, this information is not detailed enough to analyze in more detail the timing of donations for different marital histories.

To do so, we interacted the marital status with a variable grouping five years of birth (four for the first and last groups, see Table 5).

For cohabiting women, the parameter might not be well estimated at the very top of the distribution, due the small sample size of this subgroup.

For readability reason, we chose to group the cohorts into only two categories.

References

Addo, F. R., & Lichter, D. T. (2013). Marriage, marital history, and black–white wealth differentials among older women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(2), 342–362.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Bonke, J., & Grossbard, S. (2010). Income pooling and household division of labor: Evidence from Danish Couples. IZA Discussion Papers 5418, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Angelini, V., Bertoni, M., Stella, L., & Weiss, C. T. (2019). The ant or the grasshopper? The long-term consequences of Unilateral Divorce Laws on savings of European households. European Economic Review, 119, 97–113.

Behrman, J. R., Mitchell, O. S., Soo, C. K., & Bravo, D. (2012). How financial literacy affects household wealth accumulation. American Economic Review, 102(3), 300–304.

Barg, K., & Beblo, M. (2012). Does “sorting into specialization” explain the differences in time use between married and cohabiting couples? an empirical application for Germany. Annals of Economics and Statistics/Annales d’Economie et de Statistique, 127–152.

Boertien, D., & Lersch, P. M. (2019). Gendered wealth losses after dissolution of cohabitation but not marriage in germany. SOEP papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 1054, DIW Berlin, The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP).

Bonnet, C., Cambois, E., & Fontaine, F. (2021). Population Ageing in High-Longevity Countries: Demographic Dynamics and Socio-economic Challenges, Population, 2.

Bonvalet, C., Clément, C., & Ogg, J. (2015). Renewing the family: a history of the baby boomers, Springer Ined Population Studies, 4.

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I.-F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(6), 731–741.

Deere, C. D., & Doss, C. R. (2006). The gender asset gap: What do we know and why does it matter? Feminist Economics, 12(1−2), 1–50.

Dewilde, C., & Stier, H. (2014). Homeownership in later life does divorce matter?. Advances in Life Course Research, 20, 28–42.

European Commission (2021). The 2021 ageing report: economic and budgetary projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070), Institutional Paper 148.

Firpo, S. P., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2009). Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica, 77(3), 953–973.

Frémeaux, N., & Leturcq, M. (2018). Prenuptial agreements and matrimonial property regimes in France, 1855–2010. Explorations in Economic History, 68, 132–142.

Frémeaux, N., & Leturcq, M. (2020). Inequalities and the individualization of wealth. Journal of Public Economics, 184, 104–145.

Frémeaux, N., & Leturcq, M. (2022). Wealth accumulation and the gender wealth gap across couples’ legal statuses and matrimonial property regimes in France, mimeo.

Girshina, A. (2019). Wealth, savings, and returns over the life cycle: the role of education. Technical report, Working Paper.

Goldin, C., & Mitchell, J. (2017). The new life cycle of women’s employment: disappearing humps, sagging middles, expanding tops. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 161–182.

Härkönen, J., & Dronkers, J. (2006). Stability and change in the educational gradient of divorce. a comparison of seventeen countries. European Sociological Review, 22(5), 501–517. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4137342.

Heuveline, P., & Timberlake, J. M. (2004). The role of cohabitation in family formation: the United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(6), 1214–1230.

INSEE (2021). Revenus et patrimoine des ménages, Insee references, Edition 2021, 212 p.

Kapelle, N., & Baxter, J. (2021). Marital dissolution and personal wealth: Examining gendered trends across the dissolution process. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(1), 243–259

Kapelle, N., & Lersch, P. M. (2020). The accumulation of wealth in marriage: Over-time change and within-couple inequalities. European Sociological Review, 36(4), 580–593.

Kapelle, N., & Vidal, S. (2021). Heterogeneity in family life course patterns and intra-cohort wealth disparities in late working age. Eur J Population. 38, 59–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-021-09601-4.

Lersch, P. M. (2017a). Individual wealth and subjective financial well-being in marriage: Resource integration or separation? Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(5), 1211–1223.

Lersch, P. M. (2017b). The marriage wealth premium revisited: gender disparities and within-individual changes in personal wealth in Germany. Demography, 54(3), 961–983.

Leturcq, M. (2014). Marital status and mortgage in France: do unmarried couples pay a risk premium? Technical Report, Mimeo.

Lupton, J., & Smith, J. (2003). Marriage assets and savings. In S. Grossbard-Shechtman (Ed.), Marriage and the economy: Theory and evidence from advanced industrial societies. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Munnell, A. H., Sanzenbacher, G. T., King, S. E., et al. (2017). Do women still spend most of their lives married?Issue in Brief of Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, 17–14, 1–5.

OECD (2019). Pensions at a Glance 2019: OECD and G20 Indicators, Éditions OCDE, Paris.

Prioux, F., & Barbieri, M. (2012). L’évolution démographique récente en France: une mortalité relativement faible aux grands âges. Population (French Edition), 67(4), 597–656.

Rault, W., & Régnier-Loilier, A. (2015). “First cohabiting relationships: Recent trends in France”. Population & Societies, 521, 1–4.

Schneebaum, A., Rehm, M., Mader, K., & Hollan, K. (2018). The gender wealth gap across european countries. Review of Income and Wealth, 64(2), 295–331.

Sierminska, E. M., Frick, J. R., & Grabka, M. M. (2010). Examining the gender wealth gap. Oxford Economic Papers, 62(4), 669–690.

Sobotka, T., & Toulemon, L. (2008). Changing family and partnership behavior: common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demographic Research, 19(6), 85–138.

Solaz, A. (2021). More frequent separation and repartnering among people aged 50 and over. Population & Societies, 581, 1–4.

Spiers, G. F., Kunonga, T. P., Beyer, F., et al. (2021). Trends in health expectancies: a systematic review of international evidence. BMJ Open 11(5), e045567. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-04556.

Ulker, A.(2009). Wealth holdings and portfolio allocation of the elderly: the role of marital history. Journal Family and Economic Issues, 30, 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-008-9139-2.

Vespa, J., & Painter, M. A. (2011). Cohabitation history, marriage, and wealth accumulation. Demography, 48(3), 983–1004.

Wilmoth, J., & Koso, G. (2012). Does marital history matter? Marital status and wealth outcomes among preretirement adults. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 64, 254–268.

Wolff, E. N. (1998). Recent trends in the size distribution of household wealth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(3), 131–150.

Zissimopoulos, J. M., Karney, B. R., & Rauer, A. J. (2015). Marriage and economic well-being at older ages. Review of the Economics of the Household, 13, 1–35.

Funding

This research has received funds from the French Research Agency (ANR), Project Vieillir à deux, 15-CE36-0009-CN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate and publish

All authors have approved this version of the article and consent to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonnet, C., Martino, E.M., Rapoport, B. et al. Wealth inequalities among seniors: the role of marital histories across cohorts. Rev Econ Household 21, 815–853 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09633-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09633-7