Abstract

The emergence and spread of the novel coronavirus in the U.S. were quickly followed by a widespread expansion in remote work eligibility, which, in turn, led to necessary alignments between pre-existing household management schedules and new home-based work schedules for many of those who worked from home (WFH) during the COVID-19 pandemic. We use 24-hour time diary data from the 2010–2020 American Time Use Survey to examine how major daily time allocations of those who WFH changed during the pandemic compared with those who worked away from home (WAFH). Before the pandemic, we find that those who WFH spent significantly less time working, commuting to work, grooming, and eating away from home, but significantly more time sleeping, socializing, relaxing, doing housework, caring for children, shopping, preparing food, and eating at home. During the pandemic, we find generally small and statistically insignificant changes in the time allocations of those who WAFH, but several large and significant changes in uses of time for those who WFH. A noteworthy intra-pandemic increase was in time devoted to labor market work by those who WFH, which almost halved the pre-pandemic WAFH-WFH difference. Results also show large and significant reductions in time devoted to other activities during the pandemic, including work-related travel, socializing, doing housework, shopping, shopping-related travel, and eating away from home. The intra-pandemic redistribution of time by those who WFH may have health and quality-of-life implications that should be assessed as the pandemic subsides and WFH becomes a more common feature of post-pandemic life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

On March 13, 2020, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in the U.S. was declared a national emergency, which immediately changed nearly every facet of life, including the nature of work for many people living in the U.S. In response to the arrival and rapid spread of the novel coronavirus across the nation, many U.S. employers quickly implemented maximum telework policies to protect the health of their employees and to prevent further spread of the COVID-19 disease. Indeed, the share of U.S. workers who said they worked from home (WFH) because of their concern about the novel coronavirus doubled from 31% in mid-March 2020 to 62% in early April 2020.Footnote 1 Similarly, as shown in Fig. 1, the share of paid full workdays that were WFH increased over twelvefold from 5% in March 2020 to 62% in May 2020 and, as of January 2022, remains elevated at 40% (Barrero et al., 2021). In a nationally representative survey of the adult U.S. population administered in April/May of 2020, among those who were employed before the pandemic, about 15% reported that they had already been WFH since before the pandemic and an additional 35% reported recently switching to WFH during the pandemic (Brynjolfsson et al., 2020). Another nationally representative survey of the adult U.S. population found that, while the magnitudes of the WFH transitions were heterogeneous across demographic subgroups, both from February to May 2020 and from February to December 2020, the shares of workers who WFH increased during the pandemic for all demographic subgroups (Bick et al., 2021). There is also evidence that U.S. employers have expanded worksite flexibility for recently posted jobs. For example, according to LinkedIn’s Chief Economist, the number of paid U.S. jobs on LinkedIn offering remote work exploded from 1 in 67 jobs in March 2020 to 1 in 6 jobs in December 2021.Footnote 2

Share of paid full working days that were worked from home. Source: These data were pulled from the WFH Research website, https://wfhresearch.com/ (accessed March 3, 2022) (please also see Barrero et al. 2021). The underlying data come from the Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes (SWAA), which is a monthly survey of 2500+ U.S. residents aged between 20 and 64 who earned $10,000+ in 2019. The raw survey data were reweighted to match the share of the population in {age × sex × education × earnings} cells in a pooled sample of 2010–2019 Current Population Survey data

The surprise arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic may be viewed as a shock to the daily routines of those in the U.S. workforce who partially or fully shifted from on-site to home-based work. Indeed, even though the vast majority of U.S. workers could not or did not telework shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic began,Footnote 3 a recent pre-pandemic study demonstrated that daily time allocations to labor market work, leisure, and food-related activities substantially varied by place of work. Using data from the 2017–18 American Time Use Survey (ATUS) on prime working-age workers in white-collar occupations, Restrepo and Zeballos (2020) showed that WFH may free up time for some activities that are not easy to perform inside office settings and have the potential to improve health or quality of life (e.g., sleeping and food preparation).Footnote 4 Given the intra-pandemic surge in telework participation for many population subgroups (Bick et al., 2021), with approximately half of the U.S. labor force WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic (Brynjolfsson et al., 2020),Footnote 5 we build on this prior research by examining intra-pandemic daily time use patterns by place of work. Identification of intra-pandemic changes in how those who WFH allocate their time across major activities can provide insights into the potential consequences of maintaining or expanding worksite flexibility as the COVID-19 pandemic subsides.

To investigate whether and how U.S. workers allocated their time differently depending on where labor market work was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, we analyze both pre-pandemic and intra-pandemic data for all individuals from the 2010-2020 ATUS who reported spending time working a main job the day before their ATUS interview. In order to facilitate the comparison of the magnitudes of estimated effects of the COVID-19 pandemic across a dozen major activities that were determined through a data-driven selection procedure and to allow time use equation error terms to be correlated,Footnote 6 we jointly estimate time use equations in a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) framework conditional on a host of individual, household, and employment factors that can influence daily time allocations. We separately examine dual-headed and single-headed households because intrahousehold time allocation decisions can depend on whether a spouse or partner is present in the household.

While the SUR coefficient estimates varied somewhat for dual-headed versus single-headed households, the qualitative patterns were very similar. Among both types of households, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with workers who worked away from home (WAFH) during their time diary day, we find that those who WFH spent significantly less time working, commuting to work, grooming, and eating and drinking away from home, but significantly more time sleeping, socializing and communicating, relaxing and engaging in leisure, doing housework, caring for children in the household, shopping, preparing food, and eating and drinking at home.Footnote 7 Many of the WAFH-WFH wedges remained qualitatively similar during the pandemic; however, there were several large and significant time allocation changes during the pandemic that either decreased or increased wedges that existed before the pandemic, and these changes were mostly driven by redistributions made by those who WFH. Relative to sample means, the largest pre- to intra-pandemic change in time allocation for those who WFH was for labor market work and it decreased the pre-pandemic wedges by almost half. Specifically, before the pandemic, among both dual- and single-headed households, those who WFH spent about 65% less time working than those who WAFH. During the pandemic, those who WFH spent about 35% less time working than those who WAFH. The intra-pandemic working-time gap of 35% is, however, still sizeable and amounts to over 2 h when we use the working-time sample averages as a reference (470 min for dual-headed households and 458.7 min for single-headed households). Our results also show large and significant intra-pandemic decreases in allocations to work- and shopping-related travel, to potentially health-enhancing activities (socializing and eating and drinking away from home), to chores (doing housework), and to an activity that can either be a chore or a pleasant experience (shopping). Given the fixed daily time endowment, these intra-pandemic reductions may represent offsetting trade-offs from higher working-time allocations by those who WFH but may also be the result of behavior changes and restrictions on certain activities during the pandemic. While there is a lack of clarity regarding the aggregate impact of the pandemic on the health and quality of life of those who WFH, it is clear that their distribution of time across several major activities substantially changed. These findings may be useful to inform analyses of the potential costs and benefits associated with WFH as further expansions to WFH eligibility and participation are considered by future employees and employers (Barrero et al., 2021).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data used in our study and presents descriptive statistics to motivate our empirical model. Section 3 lays out the regression specification used to generate the results shown in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 provides a discussion of our results and concluding remarks.

2 Data

Our analysis relies on data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which is conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The ATUS has been administered every year since 2003 to a randomly selected subset of households that have completed their eighth and final month of Current Population Survey (CPS) interviews (BLS, 2017). One individual from each ATUS household who is at least 15 years old is interviewed by a U.S. Census Bureau representative to obtain detailed information about the activities s/he performed the day before the interview (i.e., the time diary day). Specifically, ATUS respondents are asked to identify their primary activity—if they were engaged in more than one activity at a given time—for each hour from 4 a.m. on the day before the interview to 4 a.m. on the interview day, where they were when they performed the activity, and who else was present when the activity was performed. The ATUS data include a time diary, individual and household characteristics, and employment characteristics. It is important to emphasize that the ATUS does not capture any time spent on any secondary activity performed during the time diary day. Thus, for example, if an ATUS respondent is videoconferencing with colleagues (primary activity) while eating a snack (secondary activity), the time spent snacking would not be captured in the time diary.

We now provide an overview of the sample selection criteria that we applied to 2010–2020 ATUS data. Between January 1st, 2010, and December 31st, 2020, 120,590 individuals participated in the ATUS survey.Footnote 8 Due to the difficulties of survey data collection in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, ATUS data were not collected from March 19, 2020 to May 11, 2020. Given our particular interest in analyzing time allocations by place of work, we limit our analysis to all ATUS respondents who spent any amount of time engaged in a main job during their time diary day. Although one may be concerned that work effort could be atypically high or low on the diary day, it is important to emphasize that ATUS interview dates are random with respect to the time devoted to work or any other activity the day before the interview. There is a total of 41,368 individuals who spent time working a main job the day before their interview, but our main analysis sample consists of 35,585 individuals who also have information on all the variables we use to specify our regression model. Over 2010 to 2020, approximately 14.3% of our main analysis sample exclusively WFH, 76.2% exclusively WAFH, and the remainder had a mixed workday in which either more than half of the workday was WFH (1.2 percent) or more than half of the workday was WAFH (8.4 percent). Exclusively WFH was done by approximately 13% of the pre-pandemic sample (4426 total individuals), and shot up by nearly threefold to 36.8% of the intra-pandemic sample (653 total individuals). The shares of the pre-pandemic sample and intra-pandemic sample that spent more than half their workday WFH was 1.1% (378 total individuals) and 2.4% (43 total individuals), respectively. In our analysis, we consider a worker to have WFH during their diary day if they either exclusively WFH or more than half the workday was WFH, otherwise, they are considered to have WAFH. The ATUS survey sampling weights are designed to enable the calculation of nationally representative estimates. We apply ATUS sampling weights in the calculation of all descriptive statistics and in all regression analyses shown below in order to account for the complex survey design of the ATUS and to obtain nationally representative estimates for individuals who worked a main job on an average day over 2010–2020.Footnote 9

The ATUS contains a very large number of activities, including several dozens of four-digit activity groups (e.g., eating and drinking, sleeping, and working).Footnote 10 In order to avoid an ad-hoc selection of primary activities for our analysis, we implement a data-driven rule using ATUS data from the year immediately preceding the COVID-19 pandemic (2019) and the pre-pandemic portion of 2020 (January 1, 2020 to March 12, 2020). In particular, our analysis involves all four-digit activity codes in which (a) 1 in 5 (20%) or more respondents engaged in a given four-digit activity code and (b) they spent an average of 30 min or more engaged in that four-digit activity code over the 2019 to pre-pandemic 2020 period. As shown in Appendix Table 1, our selection rule narrows our analysis to a total of 12 four-digit activity codes:Footnote 11Working, Travel related to work, Sleeping, Grooming, Socializing and communicating, Relaxing and leisure Housework, Caring for and helping household children, Shopping, Travel related to consumer purchases, Food and drink preparation, presentation, and cleanup, and Eating and drinking.Footnote 12 Taken together, on an average day over 2019 to pre-pandemic 2020, individuals who worked during their diary day spent 1327 min or 22.1 h or 92.2% of their daily time endowment on activities within these 12 four-digit activity codes.Footnote 13

To motivate the empirical specification outlined in the next section, we provide summary statistics for a wide variety of individual, household, and employment characteristics, broken down by WFH status and whether the diary was recorded before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tables 1a and 1b show several significant differences in worker characteristics, although differences across worker types within a given time period (Table 1a) are generally larger than differences across time periods within a given type of worker (Table 1b). For instance, consider the share of workers who work on an hourly basis. The pre-pandemic/intra-pandemic difference in the hourly worker share is 1 percentage point (N.S.) among those who WFH and is 5.3 percentage points (p < 0.05) among those who WAFH (Table 1b). When holding the period of time constant, differences across worker types in the share of workers who work on an hourly basis are larger (Table 1a). Before the COVID-19 pandemic began, we find that the share of workers who worked on an hourly basis was significantly higher among those who WAFH (39.8%) than among those who WFH (19.6%)—a statistically significant wedge of 20.2 percentage points (p < 0.01). This wedge grew to a statistically significant 26.5 percentage points (p < 0.01) during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was mostly driven by an increase in the share of those who WAFH being hourly workers. Given these and other significant differences in worker characteristics, all explanatory variables are always controlled for in order to reduce the risk that time use changes during COVID-19 are due to changes in the composition of workers in our estimation sample.

3 Methods

Since we are interested in how the COVID-19 pandemic affected various daily time allocations by place of work, we allow regression error terms to be correlated across time use equations and specified regression equations of the following form in a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) framework:

where T is the (inverse hyperbolic sine transformed) time spent by individual i in a given four-digit activity code;Footnote 14 δ0 is a constant term; WFH is a dummy variable equal to 1 if individual i WFH during the diary day (and 0 otherwise); COVID is a dummy variable equal to 1 if individual i was interviewed after the President of the U.S. declared a national emergency concerning the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. (March 13, 2020) (and 0 otherwise);Footnote 15 WFH×COVID is an interaction term involving the WFH dummy variable and the COVID dummy variable; X is a vector of individual, household, and employment characteristics—age, age squared, gender, presence of household children under age 6 dummy, presence of household children ages 6–11 dummy, education level, race/ethnicity, hourly worker dummy, full-time worker dummy, the logarithm of hourly wage, number of hours worked by the spouse or partner (when a partner or spouse is present), occupation dummies, and a dummy for metropolitan area residence; UR is the state-level unemployment rate where individual i resides during the month of the interview (to capture the effect of macroeconomic changes on health behavior) (Ruhm, 2005); STATE is a dummy for the state of residence of individual i (to absorb all time-invariant state characteristics, including permanent differences in health environments and prices across states); INTERVIEW is a vector of interview-related factors for individual i (dummies for year of interview, month of interview, and day of the week) that may affect time use; and εi is an idiosyncratic error term. Standard errors are clustered at the state level to allow for arbitrary correlation among observations from the same state.

In Eq. 1, the regression coefficients α, β, and γ are our coefficients of interest. The coefficient α captures the estimated effect of WFH on daily time allocations before the COVID-19 pandemic, β captures the estimated change in the time spent by those who WAFH during the COVID-19 pandemic, and γ captures the estimated change in the time spent by those who WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic. To estimate the overall effect of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic, we calculate the linear combination of the main and interaction coefficient estimates (i.e., α + γ) and test whether it is jointly statistically significant. Note that since we applied the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation to the dependent variables, the formula exp(●)−1 must be applied to the coefficient estimate in order to arrive at the percentage change (Bellemare & Wichman, 2020). Therefore, for example, the percentage change in time spent in a given activity by those who WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic is given by exp(γ)−1. In the regression tables, we report the individual regression coefficient estimates (α, β, and γ) and, for ease of interpretation, we also convert the individual regression coefficient estimate for α and the estimated linear combination of the regression coefficients α + γ into minutes per day.Footnote 16

It is important to note that individuals with a partner or spouse present in their household face different daily time constraints than do individuals without a partner or spouse present. For instance, in the former types of households, the labor supply of their spouse or partner influences their daily time allocations, while this is irrelevant for the latter types of households. Consequently, we estimate Eq. 1 for individuals for whom a spouse or partner is present and control for the number of hours worked by the spouse or partner, and we then separately estimate Eq. 1 for individuals for whom a spouse or partner is not present. For brevity, below we refer to individuals with a spouse or partner present as “dual-headed” households and individuals without a spouse or partner present as “single-headed” households.

4 Results

The regression results in Table 2 reveal that, conditional on a host of individual, household, and employment characteristics, before the pandemic, for both dual- and single-headed households there are many economically important and statistically significant differences in how time was distributed across the major activities considered. The regressions further reveal that all pre-pandemic differences that decreased or increased during the pandemic are mostly driven by intra-pandemic changes in time allocations among those who WFH during their diary day.Footnote 17

Starting with labor market work, before the pandemic, among both dual- and single-headed households, those who WFH spent significantly less time working during their diary day. Among dual- and single-headed households, before the pandemic, those who WFH spent 65% less time working than those who WAFH (i.e., 100 × [exp(−1.06)−1] = 65%). When using the sample average minutes as a reference, this translates into 306.9 fewer minutes for dual-headed households (0.65 × 470.4) and 299.4 fewer minutes for single-headed households (0.65 × 458.7). Due to large and significant intra-pandemic increases in working time by those who WFH (89% among dual-headed households and 88% among single-headed households), we find that the intra-pandemic wedges fell to about half of the pre-pandemic wedges. Among dual-headed households (single-headed households), during the pandemic, those who WFH spent 34% less time or 161.0 fewer minutes (35% less time or 159.5 fewer minutes) working than those who WAFH.

Time devoted to work-related travel was significantly lower before the pandemic among those who WFH during their diary day, amounting to 97% lower among dual-headed households and 96% lower among single-headed households. These translate into 38.9 fewer minutes and 35.9 fewer minutes relative to the sample means in time spent in work-related travel—40.2 and 37.4 min, respectively. These differences were slightly magnified during the pandemic and were driven by significant intra-pandemic decreases in time allocated to work-related travel by those who WFH. During the pandemic, those who WFH among dual-headed households spent 98% less time (or 39.4 fewer minutes), and among single-headed households spent 97% less time (or 36.3 fewer minutes) engaged in work-related travel.

Before the pandemic, we find that more time was devoted to sleeping among those who WFH, with those who WFH in dual-headed households reporting 7% more and those who WFH in single-headed households reporting 9% more time sleeping. These differences translate into 34.6 and 45.9 more minutes relative to sample means, respectively. While the interaction between the WFH and COVID dummies are negative for both groups, suggesting intra-pandemic declines in sleep among those who WFH, the interaction is statistically significant only for single-headed households. During the pandemic, we estimate that among dual-headed households, those who WFH still slept more than those who WAFH, but the sleep premium fell from 7% to 5% more time. Driven by the significant intra-pandemic decline in sleep of 6% for those who WFH among single-headed households, we find that those who WAFH an WFH spent a statistically indistinguishable amount of time sleeping during the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, we find that the amount of time spent grooming was significantly lower among those who WFH. We estimate that the pre-pandemic wedges amounted to 61% less time (or 27.5 fewer minutes) and 59% less time (or 29.1 fewer minutes) among dual-headed households and single-headed households, respectively. For both groups of households, we find that those who WFH did not significantly change the amount of time spent grooming during the pandemic, and they continued to spend significantly less time grooming themselves during the pandemic than did those who WAFH—63% less time (or 28.3 fewer minutes) among dual-headed households and 55% less time (or 27.3 fewer minutes) among single-headed households.

When it comes to socializing and communicating, before the pandemic, we find that those who WFH spent significantly more time engaged in this activity than did those who WAFH. Prior to the pandemic, compared with those who WAFH, in dual-headed households those who WFH spent 35% more time (or 7.5 more minutes), and in single-headed households those who WFH spent 33% more time (or 7.2 more minutes) socializing and communicating. This premium in socializing and communicating was eliminated during the pandemic, and was driven by significant intra-pandemic decreases of over 30% in time spent socializing and communicating among those who WFH. During the pandemic, as a result of these decreases, the differences in time spent socializing and communicating between those who WFH and WAFH during the pandemic were statistically insignificant among both dual-headed households and single-headed households.

Among both dual- and single-headed households, time spent relaxing and engaged in leisure activities by those who WFH was much higher before the pandemic, amounting to 51% more time (or 67.4 more minutes) and 54% more time (or 83.5 more minutes), respectively. These WFH-WAFH wedges grew even larger during the pandemic, which were mostly driven by larger increases in time spent engaged in this activity for those who WFH. During the pandemic, in dual-headed households those who WFH spent 83% more time (or 110.5 more minutes) and in single-headed households those who WFH spent 113% more time (or 174.0 more minutes) relaxing or engaged in leisure activities.

Among both dual- and single-headed households, time spent doing housework by those who WFH was much higher before the pandemic, but the WFH-WAFH wedges narrowed during the pandemic due to significant intra-pandemic decreases in doing housework by those who WFH of 26% and 44%, respectively. Among dual-headed households, compared with those who WAFH, we find that those who WFH went from spending 113% more time (or 17.4 more minutes) before the pandemic to spending 59% more time (or 9 more minutes) during the pandemic. Similarly, among single-headed households, the WFH-WAFH wedge fell from being 114% more time (or 16 more minutes) for those who WFH before the pandemic to being insignificantly higher during the pandemic.

Prior to the pandemic, we find that the amount of time allocated to childcare was higher for those who WFH among both dual-headed households (35% more time or 8.8 more minutes) and single-headed households (9% more time or 0.7 min). For both groups of households, the interaction between the WFH and COVID-19 pandemic dummies is negative and statistically indistinguishable from zero.Footnote 18 However, the linear combination of the WFH dummy and the interaction between the WFH and COVID pandemic dummies indicate, that childcare time remained significantly higher among those who WFH in dual-headed households (by 33% more time or 8.2 min) during the pandemic. By contrast, among single-headed households, during the pandemic, time spent on childcare for those who WFH was not significantly different from those who WAFH.

Among dual-headed households, we find that pre-pandemic shopping (shopping-related travel) was significantly higher for those who WFH by 64% or 7.9 min (by 41% or 4.2 min). However, shopping and shopping-related travel time allocations significantly declined during the pandemic among those who WFH by 36% and 34%, respectively, and resulted in those who WFH and those who WAFH spending statistically indistinguishable amounts of time engaged in shopping and travel related to shopping during the pandemic. Among single-headed households, we also find that time devoted to shopping and shopping-related travel significantly declined during the pandemic for those who WFH by 33% and 31%, respectively. Before the pandemic, those who WFH spent a significantly higher amount of time shopping (27% or 3.1 more minutes) and an insignificantly higher amount of time engaged in shopping-related travel. However, as a result of intra-pandemic declines in shopping and shopping-related travel time for those who WFH, during the pandemic they ended up spending an insignificantly lower amount of time shopping and a significantly lower amount of time engaged in shopping-related travel (26% or 2.5 fewer minutes).

Among both dual- and single-headed households, those who WFH spent significantly more time before the pandemic engaged in food production activities. Compared with those who WAFH, pre-pandemic food production time was significantly higher by 94% (or 25.2 more minutes) and 68% (or 12.7 more minutes), respectively. There were no statistically significant intra-pandemic changes in the amount of time spent preparing food by those who WFH. During the pandemic, food production time allocation remained significantly higher for those who WFH among dual-headed households (by 81% or 21.8 more minutes) and among single-headed households (by 96% or 17.9 more minutes).

Those who WFH devoted more time to at-home eating and drinking before the pandemic than did those who WAFH among dual-headed households (126% or 42.8 more minutes) and single-headed households (148% or 37.2 more minutes). Among dual-headed households, we find a significant intra-pandemic increase of 27% in time devoted to at-home eating and drinking. As a result, the WFH-WAFH wedge grew larger during the pandemic, with those who WFH spending 186% (or 63.4 more minutes) among dual-headed households. Among single-headed households, the intra-pandemic change in time devoted to at-home eating by those who WFH is insignificant but positive and similar in magnitude to the corresponding one for dual-headed households. We estimate that those who WFH among single-headed households continued to spend more time than those who WAFH engaged in this activity (211% or 53.1 more minutes) during the pandemic.

A mirror-image pattern emerges for eating and drinking away from home, with eating and drinking away from home significantly decreasing during the pandemic for those who WFH by 56% in dual-headed households and 57% in single-headed households. As a result, pre-pandemic WAFH-WFH wedges increased during the pandemic. Among dual-headed households, those who WFH spent significantly fewer minutes than did those who WAFH eating and drinking away from home before the pandemic (76% or 21.9 fewer minutes) and during the pandemic (90% or 25.7 fewer minutes). Similarly, among single-headed households, away-from-home eating and drinking was significantly lower by 77% (or 23.1 fewer minutes) before the pandemic and by 90% (or 27.1 fewer minutes) during the pandemic.

5 Discussion and concluding remarks

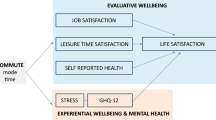

To facilitate the discussion, in Fig. 2, we draw from Table 2 but only summarize the statistically significant estimates of the intra-pandemic changes in time allocations for those who WFH, ranked by the percentage change of the estimate. The results for allocations to labor market work stand out clearly for both groups of households, showing very large increases in working by those who WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among dual- and single-headed households, compared with those who WAFH, those who WFH showed positive intra-pandemic shifts of 89% and 88%, respectively. However, those who WFH reduced time allocations to several other major activities during the pandemic, including work-related travel, doing housework, shopping, shopping-related travel, socializing, and eating away from home. This redistribution of time may be the result of a combination of trade-offs from a higher daily allocation to working as well as pandemic-linked behavior changes and restrictions on certain activities.

Estimated intra-pandemic percentage changes in time allocations for those who WFH. Notes: These are based on statistically significant estimates of the interaction between WFH and the COVID pandemic dummy shown in Table 2. Source: Authors’ calculations, using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2010–2020 ATUS

Two of these intra-pandemic reductions in time allocations may have implications for the health outcomes of those who WFH vis-à-vis WAFH. Relative to sample means, the largest negative percentage change is for eating away from home, which may have been partly driven by foodservice establishment closures and social distancing to avoid transmitting or contracting the novel coronavirus. Our estimates indicate that, among dual- and single-headed households, time devoted to eating away from home by those who WFH dropped by 56% and 57%, respectively. A large body of literature has shown that eating food prepared away from home (FAFH) tends to put upward pressure on calorie intake and downward pressure on diet quality (Davis, 2014; Monsivais et al., 2014; Saksena et al., 2018; Todd et al. 2010; Wolfson & Bleich, 2015; Wolfson et al., 2020). The ATUS data do not contain any information on the quantity or quality of foods consumed away from home, but our results do suggest that WFH may have enabled less reliance on FAFH for daily food needs. That said, weight gain and higher obesity prevalence among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported by a number of studies (Bhutani et al., 2021; Flanagan et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021; Restrepo 2022; Seal et al., 2022; Zeigler et al., 2020), so future research into whether WFH leads to more healthful eating behavior is warranted.

The second intra-pandemic change in the time allocations of those who WFH that may have health implications is time devoted to socializing and communicating. Among dual- and single-headed households, socializing and communicating by those who WFH dropped by 32% and 31%, respectively. These reductions may also have, in part, been driven by foodservice and entertainment venue closures and social distancing during the pandemic. Research shows that physically distancing from others is associated with negative mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Pandi-Perumal et al., 2021). However, the results for relaxing and engaging in leisure somewhat offset the concern regarding the intra-pandemic decreases in socializing and communicating for those who WFH. We find a large and significant intra-pandemic increase of 21% in time devoted to relaxing and engaging in leisure by those who WFH among dual-headed households. Moreover, we find that, during the pandemic, significantly higher amounts of time were devoted to relaxing and engaging in leisure for those who WFH in both dual-headed households (83% more time) and single-headed households (113% more time).

In conclusion, to promote and protect health during the COVID-19 pandemic, many U.S. employers switched to remote work environments and employees performed some or all of their work duties from their own homes rather in offices. This can be disruptive to households that need to align new home-based work schedules with pre-existing household management schedules. Indeed, the study results reveal that, at least in the first year of the pandemic, those who WFH reallocated several major uses of time, which may have been done in part to accommodate the sizeable increase in the amount of work being performed inside of their homes. The intra-pandemic reallocation of time by those who WFH also revealed less time allocated to chores such as housework, to health-promoting activities such as socializing with others, and to experiences such as shopping that can be a chore or a pleasant pastime. An investigation into what caused these changes—e.g., retail store closures and cuts in hours of operation—is beyond the scope of this study, but it is certainly worthy of the future attention of researchers. The aggregate effects of WFH versus WAFH on health and quality of life are also unclear. As the COVID-19 pandemic and associated shocks to the labor force in the U.S. sunset, since increased WFH availability may be the post-pandemic normal (Barrero et al., 2021), it is important for future research to assess the totality of health and quality-of-life effects associated with the time allocations of those who WFH. A major strength of this study is the ability to estimate intra-pandemic changes in time use patterns by place of work using a large nationally representative survey. The ATUS is, however, a cross-sectional survey, and future research exploiting longitudinal data to explore the dynamics of time use among the same individuals would be particularly useful in measuring the costs and benefits of shifting work effort from offices to homes.

Data availability

This research uses information from public use data of the American Time Use Survey: https://www.bls.gov/tus/

Code availability

All analyses were conducted using the survey-related commands in the statistical software package Stata, version 17. The code is available upon request.

Change history

07 July 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09618-6

Notes

These data were drawn from an article titled “U.S. Workers Discovering Affinity for Remote Work” by Megan Brenan, which can be found here: https://news.gallup.com/poll/306695/workers-discovering-affinity-remote-work.aspx (accessed March 3, 2022).

These data were drawn from an article titled “What Will the World of Work Look Like in 2022? Expect Employees To Remain in the Driver’s Seat, Demanding More Out of Work” by Karin Kimbrough, which can be found here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-world-work-look-like-2022-expect-employees-remain-kimbrough/ (accessed March 3, 2022).

Over the 2017-18 period, about 1 in 3 wage and salary workers could WFH in their primary job and 1 in 4 WFH at least occasionally (BLS, 2020).

Pabilonia and Vernon (2022) also find evidence suggesting that WFH may improve work-life balance using 2017–18 ATUS data. For example, among men, they found that teleworkers spent more time eating their meals and caring for family members on home days than on office days. And, among women, they found that teleworkers devoted more time to home production activities and sleep on home days than on office days, the latter of which may lead to higher productivity during the workday.

In “Remote Work Persisting and Trending Permanent” by Lydia Saad and Ben Wigert, data from a Gallup Panel the share of full-time employees who WFH ranged from 69% in May 2020 to 45% in September 2021 (please see https://news.gallup.com/poll/355907/remote-work-persisting-trending-permanent.aspx, accessed March 3, 2022)

Overall, the 12 major activities account for over 92.3% of our sample’s daily time endowment. Specifically, they account for 92.5% of the dual-headed households’ endowment and 92.0% of the single-headed households’ endowment.

These results are consistent with those of Restrepo and Zeballos (2020) who find using 2017-18 ATUS data that WFH is associated with less time working and on personal care, but more time on leisure, sleeping, and on food production and consumption.

As such, we cannot exploit the variation in time spent at home caused by shelter-in-place orders, which were implemented between March and April 2020 (Dave et al., 2021).

The CPS has both a stratified and clustered sampling procedure and thus is nonrandom; the ATUS follows a similar sampling procedure. We performed the balanced repeated replication (BRR) method using the final and replicate weights and a Fay coefficient of 0.5 to generate standard errors that are more precise than a method assuming a random sample.

Please see the 2003–2020 multi-year activity coding lexicon for a full list of four-digit activity codes, available at https://www.bls.gov/tus/lexiconnoex0320.pdf (accessed March 3, 2022).

Please see Appendix Tables 2a and 2b for all activities contained within each 4-digit activity code.

In the regression analysis, because the quantity and quality of food intake varies by whether or not it is prepared at home (Davis, 2014; Monsivais et al., 2014; Saksena et al, 2018; Todd et al., 2010; Wolfson & Bleich, 2015; Wolfson et al., 2020), we use information on where the activity is performed to separately consider eating and drinking (at home) and eating and drinking (away from home).

On an average day over 2010–2020, individuals who worked during their diary day spent 1318 min or 22 h or 91.5% of their daily time endowment on activities within these 12 four-digit activity codes.

We transform the right-skewed activity variables in order to better approximate normal distributions. Specifically, we use the Stata command asinh (i.e., inverse hyperbolic since transformation) since we have observations with zero time use (i.e., respondents who did not engage in a given activity).

Specifically, since BLS did not collect ATUS data from March 19, 2020 to May 11, 2020, the COVID dummy equals 0 from January 1, 2010 until data collection stopped on March 18, 2020, and equals 1 when data collection restarted on May 12, 2020 until December 31, 2020.

In order to translate the estimated regression coefficient or linear combination of coefficients into minutes per day, we use the relevant subsample average for a given activity (e.g., either dual-headed households or single-headed households). Since the dependent variables involve the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation of time spent engaged in a given activity, the formula (exp(●)-1)×x̄ is applied where x̄ is a subsample’s average.

To facilitate comparison of our previous results using pre-pandemic data (Restrepo & Zeballos, 2020), we repeat these analyses for prime working-age individuals in white-collar occupations who provided diary data for weekdays (Appendix Table 3). This subsample is much smaller, but the regression patterns are generally qualitatively similar to those in Table 2.

We also re-estimated our SUR models using a subsample of ATUS respondents who have children and found similar patterns (results available upon request).

References

Barrero, J. M., Bloom N., & Davis S. J. (2021). Why working from home will stick. NBER Working Paper 28731.

Bellemare, M. F., & Wichman, C. J. (2020). Elasticities and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 50–61.

Bhutani, S., vanDellen, M. R., & Cooper, J. A. (2021). Longitudinal weight gain and related risk behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in adults in the US. Nutrients, 13(2), 671.

Bick, A., Blandin A., & Mertens K. (2021). Work from home before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. Working Paper. Available at SSRN: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3786142.

Brynjolfsson, E., Horton J. J., Ozimek A., Rock D., Sharma G., & TuYe H.-Y. (2020). COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at U.S. data. NBER Working Paper 27344.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2017). American Time Use Survey (ATUS) User’s Guide: Understanding ATUS 2003 to 2016, U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, June.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2020). Job Flexibilities and Work Schedules—2017–18, U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, September.

Dave, D., Friedson, A. I., Matsuzawa, K., & Sabia., J. J. (2021). When do shelter-in-place orders fight COVID-19 best? Policy heterogeneity across states and adoption time. Economic Inquiry, 59(1), 29–52.

Davis, G. C. (2014). Food at home production and consumption: Implications for nutrition quality and policy. Review of Economics of the Household, 12, 565–588.

Flanagan, E. W., Beyl, R. A., Fearnbach, S. N., Altazan, A. D., Martin, C. K., & Redman, L. M. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults. Obesity, 29(2), 438–445.

Lin, A. L., Vittinghoff, E., Olgin, J. E., Pletcher, M. J., & Marcus, G. M. (2021). Body weight changes during pandemic-related shelter-in-place in a longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), e212536.

Monsivais, P., Aggarwal, A., & Drewnowski, A. (2014). Time spent on home food preparation and indicators of healthy eating. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(6), 796–802.

Pabilonia, S. W., & Vernon, V. (2022). Telework, wages, and time use in the United States. Review of Economics of the Household, In Press

Pandi-Perumal, S. R., Vaccarino, S. R., & Chattu, V. K., et al. (2021). ‘Distant socializing’, not ‘social distancing’ as a public health strategy for COVID-19. Pathogens and Global Health, 115(6), 357–364.

Restrepo, B. J. 2022. Obesity prevalence among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, In Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.01.012.

Restrepo, B. J., & Zeballos, E. (2020). The effect of working from home on major time allocations with a focus on food-related activities. Review of Economics of the Household, 18, 1165–1187.

Ruhm, C. (2005). Healthy living in hard times. Journal of Health Economics, 24(2), 341–363.

Saksena, M. J., Okrent, A. M., Anekwe, T. D., Cho, C., Dicken, C., Effland, A., Elitzak, H., Guthrie, J., Hamrick, K. S., Hyman, J., Jo, Y., Lin, B.-H., Mancino, L., McLaughlin, P. W., Rahkovsky, I., Ralston, K., Smith, T. A., Stewart, H., Todd, J., & Tuttle, C. (2018). America’s eating habits: food away from home, EIB-196, Michelle Saksena, Abigail M. Okrent, and Karen S. Hamrick, eds. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, September.

Seal, A., Schaffner, A., Phelan, S., Brunner-Gaydos, H., Tseng, M., Keadle, S., Alber, J., Kiteck, I., & Hagobian, T. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home mandates promote weight gain in US adults. Obesity, 30(1), 240–248.

Todd, J. E., Mancino, L., & Lin, B.-H. (2010). The impact of food away from home on adult diet quality, ERR-90, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, February.

Wolfson, J. A., & Bleich, S. N. (2015). Is cooking at home associated with better diet quality or weight-loss intention? Public Health Nutrition, 18(8), 1397–1406.

Wolfson, J. A., Leung, C. W., & Richardson, C. R. (2020). More frequent cooking at home is associated with higher Healthy Eating Index-2015 Score. Public Health Nutrition, 23(13), 2384–2394.

Zeigler, Z., Forbes, B., Lopez, B., Pedersen, G., Welty, J., Deyo, A., & Kerekes, M. (2020). Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 14(3), 210–216.

Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors had equal roles in formulating the research question and writing the article. The corresponding author initiated the research and the second author analyzed the data.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix Table 1: Share of individuals who engaged in an activity (and average minutes when engaged) over the 2019 to pre-pandemic 2020 period, by 4-digit activity code

Primary Activity (4-Digit Activity Code) | Percent engaged | Average minutes when engaged |

|---|---|---|

Working (0501) | 100% | 465.7 |

Travel related to work (1805) | 84% | 46.9 |

Sleeping (0101) | 100% | 481.9 |

Grooming (0102) | 92% | 51.7 |

Socializing and communicating (1201) | 30% | 68.2 |

Relaxing and leisure (1203) | 86% | 157.1 |

Housework (0201) | 23% | 57.4 |

Caring for & helping household children (0301) | 24% | 78.7 |

Shopping (store, telephone, internet) (0701) | 35% | 31.4 |

Travel related to consumer purchases (1807) | 33% | 30.9 |

Food & drink preparation, presentation, & clean-up (0202) | 59% | 43.3 |

Eating and drinking (1101) | 96% | 60.3 |

Appendix Table 2: Activity codes used in the analysis

Working (0501) |

050101: Work, main job |

050189: Working, n.e.c. |

050103: Security procedures related to work |

050189: Working, n.e.c. |

Travel related to work (1805) |

180501: Travel related to working |

180502: Travel related to work-related activities |

180589: Travel related to work, n.e.c. |

Sleeping (0101) |

010101: Sleeping |

010102: Sleeplessness |

010199: Sleeping, n.e.c. |

Grooming (0102) |

010201: Washing, dressing, and grooming oneself |

010299: Grooming, n.e.c. |

Socializing and communicating (1201) |

120101: Socializing and communicating with others |

120199: Socializing and communicating, n.e.c. |

Relaxing and leisure (1203) |

120301: Relaxing, thinking |

120302: Tabaco and drug use |

120305: Listening to the radio |

120306: Listening to/playing music (not radio) |

120307: Playing games |

120308: Computer use for leisure (exc. Games) |

120309: Arts and crafts as a hobby |

120310: Collecting as a hobby |

120311: Hobbies, except arts and crafts and collecting |

120312: Reading for personal interest |

120313: Writing for personal interest |

120399: Relaxing and leisure, n.e.c. |

Housework (0201) |

020101: Interior cleaning |

020102: Laundry |

020103: Sewing, repairing, and maintaining textiles |

020104: Storing interior hh items, including food |

020199: Housework, n.e.c. |

Caring for and helping household children (0301) |

030101: Physical care for hh children |

030102: Reading to/with hh children |

030103: Playing with hh children, not sports |

030104: Arts and crafts with hh children |

030105: Playing sports with hh children |

030186: Talking with/listening to hh children |

030108: Organization & planning for hh children |

030109: Looking after hh children (as a primary activity) |

030110: Attending hh children’s events |

030111: Waiting for/with hh children |

030112: Picking up/dropping off hh children |

030199: Caring for & helping hh children, n.e.c. |

Shopping (store, telephone, internet) (0301) |

070101: Grocery shopping |

070102: Purchasing gas |

070103: Purchasing food (not groceries) |

070104: Shopping, except groceries, food and gas |

070105: Waiting associated with shopping |

070199: Shopping, n.e.c. |

Travel related to consumer purchases (1807) |

180701: Travel related to grocery shopping |

180782: Travel related to shopping (except grocery shopping) |

Food and drink preparation, presentation, and clean-up (0202) |

020201: Food and drink preparation |

020299: Food and drink preparation, presentation, and clean-up, n.e.c. |

020202: Food presentation |

020203: Kitchen and food clean-up |

Grocery shopping |

070101: Grocery shopping |

180701: Travel related to grocery shopping |

Eating and drinking (1101) |

110101: Eating and drinking |

110199: Eating and drinking, n.e.c. |

Appendix Table 3: Coefficients and standard errors from seemingly unrelated regressions of time spent in major activities associated with COVID and other worker characteristics (Sample restricted to prime working-age individuals working in white-collar occupations on weekdays)

Dep Var [Time spent in minutes] | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Working | Travel related to work | Sleeping | Grooming | Socializing and communicating | Relaxing and leisure | Housework | Caring for and helping HH children | Shopping | Travel related to consumer purchases | Food/Drink Prep | Eating and drinking at home | Eating and drinking away from home | ||

Spouse or partner present | ||||||||||||||

γ | COVID x WFH | 0.53 (0.071)*** | −0.31* (0.175) | −0.04 (0.027) | 0.10 (0.230) | −0.72** (0.308) | 0.13 (0.192) | 0.13 (0.136) | 0.15 (0.218) | −0.32 (0.259) | −0.33 (0.255) | 0.22 (0.236) | 0.24 (0.231) | −0.58** (0.245) |

β | COVID | −0.02 (0.075) | −0.12 (0.175) | 0.06** (0.028) | 0.11 (0.187) | −0.10 (0.253) | 0.17 (0.234) | −0.47** (0.223) | −0.11 (0.202) | −0.19 (0.262) | −0.26 (0.256) | −0.23 (0.255) | 0.28 (0.265) | −0.45 (0.340) |

α | WFH | −0.82 (0.053)*** | −3.56*** (0.062) | 0.07*** (0.009) | −1.07*** (0.105) | 0.28*** (0.086) | 0.39*** (0.087) | 0.48*** (0.085) | 0.28*** (0.076) | 0.17*** (0.063) | 0.07 (0.068) | 0.46*** (0.100) | 0.77*** (0.068) | −1.63*** (0.093) |

Percentage changes applied to overall sample means | ||||||||||||||

α | WFH (before pandemic) | −274.1*** | −40.0*** | 32.5*** | −30.4*** | 6.5*** | 54.0*** | 8.6*** | 11.3*** | 2.1*** | 0.7 | 16.4*** | 38.5*** | −23.4*** |

α + γ | WFH (during pandemic) | −123.6*** | −40.3*** | 12.5 | −28.7*** | −7.1 | 76.7*** | 11.7*** | 18.8** | −1.6 | −2.3 | 27.5*** | 58.2*** | −25.9*** |

Average minutes spent in the activity | 488.9 | 41.1 | 462.5 | 46.2 | 20.1 | 111.7 | 13.9 | 35.2 | 11.5 | 10.0 | 27.8 | 33.3 | 29.1 | |

Number of observations | 7483 | |||||||||||||

Spouse or partner NOT present | ||||||||||||||

γ | COVID x WFH | 0.38 (0.108)*** | −0.03 (0.179) | −0.04 (0.051) | 0.39 (0.320) | −0.44 (0.349) | −0.07 (0.359) | −0.14 (0.316) | 0.23 (0.158) | −0.43 (0.278) | −0.41 (0.282) | 0.68* (0.410) | 0.36 (0.331) | −0.83** (0.369) |

β | COVID | −0.06 (0.079) | −0.03 (0.204) | 0.04 (0.049) | 0.04 (0.272) | 0.61 (0.491) | 0.56 (0.431) | 0.64* (0.367) | −0.17 (0.214) | −0.17 (0.501) | −0.30 (0.514) | −0.28 (0.602) | −0.14 (0.434) | −0.02 (0.435) |

α | WFH | −0.58 (0.077)*** | −3.51*** (0.091) | 0.07*** (0.016) | −0.88*** (0.124) | 0.21 (0.173) | 0.40** (0.171) | 0.19 (0.121) | 0.16** (0.077) | 0.13 (0.182) | 0.07 (0.178) | 0.34** (0.173) | 0.85*** (0.134) | −1.62*** (0.190) |

Percentage changes applied to overall sample means | ||||||||||||||

α | WFH (before pandemic) | −218.5*** | −40.0*** | 33.8*** | −29.6*** | 4.5 | 64.2** | 2.2 | 1.7** | 1.6 | 0.9 | 8.2** | 33.6*** | −26.2*** |

α + γ | WFH (during pandemic) | −87.1*** | −40.0*** | 13.8 | −19.6 | −4.0 | 51.7 | 0.5 | 4.5*** | −2.9 | −3.1 | 35.9*** | 58.7*** | −29.9*** |

Average minutes spent in the activity | 499.3 | 41.2 | 471.3 | 50.8 | 19.5 | 130.9 | 11.1 | 9.5 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 20.0 | 25.2 | 32.7 | |

Number of observations | 3885 | |||||||||||||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Restrepo, B.J., Zeballos, E. Work from home and daily time allocations: evidence from the coronavirus pandemic. Rev Econ Household 20, 735–758 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09614-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09614-w