Abstract

Discrete choice experiments (DCE) are increasingly used to quantify the demand for improvements to services provided by regulated utility companies and inform price controls. This form of preference elicitation, however, often reveals a high frequency of status quo (SQ) choices. This may signal an unwillingness of respondents to evaluate the proposed trade-offs in service levels, questioning the welfare theoretic interpretation of observed choices and the validity of the approach for regulatory purposes. Using the methodology for DCE in the regulation of water and sewerage services in England and Wales, our paper contributes to the understanding of SQ choices in several novel dimensions. First, we control for the perception of the SQ and the importance of attributes in day-to-day activities. Second, we use a split sample design to vary both the description of the SQ and the survey administration mode (online vs. in-person). Third, the service attributes can both improve or deteriorate, so that the SQ is not necessarily the least-cost option. Fourth, we examine SQ choices in individual choice tasks and across all tasks so as to identify the determinants of serial SQ choices. Our results suggest that individual SQ choices mostly reflect preferences and thus represent important information for the regulator. However, serial SQ choices are mainly driven by cognitive and/or contextual factors, and these responses should be analysed as part of standard validity tests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Based on the assumption that consumers derive utility from characteristics of products (Lancaster 1966; Rosen 1974), a DCE simulates market transactions by constructing sets of alternative combinations of attributes (service characteristics) and requires respondents to select their most preferred alternative in a number of choice occasions. Trading-off various aspects of service provision with changes in utility bills reveal preferences for independent changes in each attribute. Originally applied in the context of transportation (Ben-Akiva and Lerman 1985), its application in recent years has encompassed marketing (e.g. Zwerina 1997), health (e.g. Ryan 1999), and the environment (e.g. Adamowicz et al. 1994).

The Water Services Regulation Authority (Ofwat) regulates price-setting among water and sewerage companies in England and Wales. The amount by which consumer bills can change over time is determined by the five-yearly Price Review process, through which Ofwat scrutinises the proposed business plans of the regulated companies. It has been established that plans should be informed by the systematic comparison of the costs and benefits of service improvements (e.g. Ofwat 2007), and explicitly take into account the preferences of customers (Ofwat 2011).

In the context of regulation in England and Wales, the widespread use of DCEs in the development of utilities’ investment plans has generated significant scrutiny of stated preference methods by all stakeholders involved in the process (including the companies themselves, the regulator, and consumer representative groups, see UKWIR 2010).

There exist a number of other empirical challenges associated with the use of DCEs. These include hypothetical bias (Diamond and Hausman 1994; List 2001), incentive compatibility of the choice format (Harrison 2007), task complexity (Swait and Adamowicz 2001), and preference ‘anomalies’ (Bateman et al. 2009; Day and Prades 2010). Importantly, evidence from controlled field experiments have provided empirical support for the DCE approach to estimate marginal WTP in terms of hypothetical bias (List et al. 2006). Further, Vossler et al. (2012) have shown that DCEs can induce truthful revelation of preferences if choices are perceived to have a chance of affecting policy. While these issues are not directly studied in the present paper, the design of our survey instrument builds on these results to minimise their potential implications.

A status quo ‘bias’ can be interpreted as a manifestation of loss aversion in a multiple good context (see Rabin 1998, for a discussion). SQ choices may then be due to implications of losses appearing larger than the gains of other goods.

Two early papers by Hartman et al. (1990, 1991) studied the propensity of respondents to stay with the SQ in a contingent valuation survey evaluating the demand for electric service reliability. While these paper document what is called a SQ ‘bias’, they do not study the determinants of these choices.

The SQ ASC, together with an additional error term (or error component), controls for the role of unobserved sources of utility for the SQ and captures the fact that the perception of the SQ may systematically differ from the experimentally specified alternatives. However, while a positive SQ ASC to rationalise observed choices provides direct evidence about the prevalence of the SQ option in DCE choices (or its market share), it is inherently difficult to assess whether it reflects preferences for the SQ or whether it is a feature of the preference elicitation method.

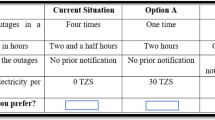

Figures are rounded for easier interpretation by respondents based on testing in focus groups and cognitive interviews.

In particular, this allows us to check that restricting the sample to the first block of services presented does not alter the welfare estimates.

Because we use an efficient experimental design, and have multiple observation per respondent, the sample of respondents is relatively modest. As we show below, the chosen sample size achieved the objective since all marginal WTP estimates are preciesly estimated.

This specification mirrors the error-component structure introduced by Scarpa et al. (2007) which allows the scale of the error variance to differ between the SQ option and the hypothetical alternatives. We favour the random parameter interpretation of the SQ ASC in this analysis as it provides direct evidence on preference heterogeneity for the SQ.

The model is estimated with simulated maximum likelihood, and we use 500 Halton draws to approximate the integral of the unconditional likelihood of each panel choices. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level to account for the fact that each respondent makes four different choices for each block of service.

Table 3 Discrete choice experiment: WTP-space estimation Interaction terms between these two variables were also tested but did not yield further insights.

Because of imbalances across subsamples in terms of preferences for the SQ, it may be the case that the impact of preferences for the SQ is driven by the inclusion of the online subsample. As we report in Appendix B, the main conclusions from our analysis, and in particular the importance of preferences for the SQ, are preserved if we restrict the sample to just the CAPI subsamples.

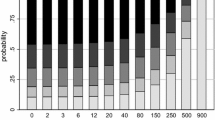

All other variables included are at the sample mean.

Note that we do not find evidence supporting the presence of non-linearities for these variables.

As for the individual SQ choices restricting the sample to CAPI respondents only does not affect our main conclusions (see Appendix C).

Again all other variables are kept at the sample mean.

References

Adamowicz, W., Louviere, J., & Williams, M. (1994). Combining stated and revealed preference methods for valuing environmental attributes. Journal of Environmental Economics and Managment, 26, 271–292.

Adamowicz, W., Boxall, P., Williams, M., & Louviere, J. (1998). Stated preference approaches for measuring passive use values: choice experiments and contingent valuation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 80, 64–75.

Bateman, I., Carson, R., Day, B., Hanemann, W., Hanley, N., Hett, T., et al. (2002). Economic valuation with stated preference techniques: A manual. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bateman, I., Day, B., Jones, A., & Jude, S. (2009). Reducing gain - loss asymmetry: A virtual reality choice experiment valuing land use change. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 58(1), 106–118.

Ben-Akiva, M., & Lerman, S. (1985). Discrete choice analysis: Theory and application to travel demand. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Boxall, P., Adamowicz, W., & Moon, A. (2009). Complexity in choice experiments: Choice of the status quo alternative and implications for welfare measurement. The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 53, 503–519.

Cummings, R., & Taylor, L. (1999). Unbiased value estimates for environmental goods: A cheap talk design for the contingent valuation method. American Economic Review, 89(3), 649–665.

Day, B., & Prades, J. P. (2010). Ordering anomalies in choice experiments. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 59, 271–285.

Diamond, P., & Hausman, J. (1994). Contingent valuation: is some number better than no number. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(4), 45–64.

Freeman, A. (1986). On assessing the state of the arts of the contingent valuation method valuing environmental changes. In R. Cummings, D. Brookshire, & W. Schulze (Eds.), Valuing environmental goods: An assessment of the contingent valuation method. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Allanheld Publishers.

Halstead, J., Luloff, A., & Stevens, H. (1992). Protest bidders in contingent valuation. Northeastern Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 21(2), 160–169.

Hanley, N., Wright, R. E., & Alvarez-Farizo, B. (2006). Estimating the economic value of improvements in river ecology using choice experiments: An application to the water framework directive. Journal of Environmental Management, 78(2), 183–193.

Harrison, G. (2007). Making choice studies incentive compatible. In B. Kanninen (Ed.), Valuing environmental amenities using stated choice studies. A common sense approach to theory and practice (pp. 67–110). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hartman, R., Donae, M., & Woo, C. (1990). Statusquo bias in the measurement of value of service. Resources and Energy, 12(2), 197–214.

Hartman, R., Donae, M., & Woo, C. (1991). Consumer rationality and the status quo. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(1), 141–162.

Hensher, D., Stopher, P., & Louviere, J. (2001). An exploratory analysis of the effects of numbers of choice sets in designed choice experiments: An airline choice application. Journal of Air Transport Management, 7, 373–379.

Hess, S., & Rose, J. (2009). Should reference alternatives in pivot design SC surveys be treated differently? Environmental and Resource Economics, 42(3), 297–317.

Lancaster, K. J. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74, 132–157.

Landry, C., & List, J. (2007). Using ex ante approaches to obtain credible signals for value in contingent markets: Evidence from the field. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 89(2), 420–429.

Lanz, B., Provins, A., Bateman, I., Scarpa, R., Willis, K., & Ozdemiroglu, E. (2010). Investigating willingness to pay—willingness to accept asymmetry in choice experiments. In S. Hess & A. Daly (Eds.), Choice modelling: The state-of-the-art and the state-of-practice. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Lindhjem, H., & Navrud, S. (2011). Are internet surveys an alternative to face-to face interviews in contingent valuation? Ecological Economics, 70(9), 1628–1637.

List, J. (2001). Do explicit warnings eliminate the hypothetical bias in elicitation procedures? evidence from field auctions for sportscards. Americal Economic Review, 91(5), 1498–1507.

List, J. A., Sinha, P., & Taylo, M. H. (2006). Using choice experiments to value non-market goods and services: Evidence from field experiments. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy in Advances, 5(2), 5.

Louviere, J., & Hensher, D. (1982). On the design and analysis of simulated choice or allocation experiments in travel choice modelling. Transportation Research Record, 890, 11–17.

Louviere, J., & Woodworth, G. (1983). Design and analysis of simulated consumer choice or allocation experiments: An approach based on aggregate data. Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 350–367.

Marsh, D., Mkwara, L., & Scarpa, R. (2011). Do respondents perceptions of the status quo matter in non-market valuation wich choice experiments? An application to new zeland freshwater streams. Sustainability, 3, 1593–1615.

Meyerhoff, J., & Liebe, U. (2009). Status quo effect in choice experiments: Empriical evidence on attitudes and choice task complexity. Land Economics, 85(3), 515–528.

Nielsen, J. S. (2011). Use of the internet for willingness-to-pay surveys. A comparison of face-to-face and web-based interviews. Resource and Energy Economics, 33(1), 119–129.

Ofwat. (2007). Further ofwat guidance on the use of cost-benefit analysis for PR09. Letter to all regulatory directors of water and sewerage companies and water only customers, Fiona Pethick, Ofwat Director of Corporate Affairs. http://www.ofwat.gov.uk/pricereview/pr09phase1/pr09phase1letters/ltr_pr0908_cbaguide, Accessed November 2014.

Ofwat. (2011). Involving customers in price setting—Ofwat’s customer engagement policy statement. http://www.ofwat.gov.uk/future/monopolies/fpl/customer/pap_pos20110811custengage.pdf, Accessed November 2014.

Rabin, M. (1998). Psychology and economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(1), 11–46.

Revelt, D., & Train, K. (1998). Mixed logit with repeated choices: Households’ choices of appliance efficiency level. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 647–657.

Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Product differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 34–55.

Ryan, M. (1999). A role for conjoint analysis in technology assessment in health care? International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 15, 443–457.

Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1, 7–59.

Scarpa, R., Ferrini, S., & Willis, K. (2005). Performance of error component models for status-quo effects in choice experiments. In R. Scarpa & A. Alberini (Eds.), Applications of simulation methods in environmental and resource economics. Dordrecht: Springer.

Scarpa, R., Willis, K., & Acutt, M. (2007). Valuing externalities from water supply: Status quo, choice complexity and individual random effects in panel kernel logit analysis of choice experiments. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 50(4), 449–466.

Street, D., & Burgess, L. (2007). The construction of optimal stated choice experiments: Theory and methods. Hoboken: Wiley-Interscience.

Swait, J., & Adamowicz, W. (2001). The influence of task complexity on consumer choice: a latent class model of decision strategy switching. Journal of Consumer Research, 28, 135–148.

Train, K., & Weeks, M. (2005). Discrete choice models in preferrence space and willingness-to-pay space. In R. Scarpa & A. Alberini (Eds.), Applications of simulation methods in environmental and resource economics (pp. 1–16). Dordrecht: Springer.

UKWIR. (2010). Review of cost-benefit analysis and benefit valuation. Report Ref. No. 10/RG/07/18.

Viscusi, W. K., & Huber, J. (2012). Reference-dependent valuations of risk: Why willingness-to-accept exceeds willingness-to-pay. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 44(1), 19–44.

Von Haefen, R., D.M., M., & Adamowicz, W. (2005). Serial nonparticipation in repeated discrete choice models. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87(4), 1061–1076.

Vossler, C. A., Doyon, M., & Rondeau, D. (2012). Truth in consequentiality: Theory and field evidence on discrete choice experiments. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 4(4), 145–171.

Willis, K., McMahon, P., Garrod, G. D., & Powe, N. (2002). Water companies’ service performance and environmental trade-offs. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 45(3), 363–379.

Willis, K., Scarpa, R., & Acutt, M. (2005). Assessing water company customer preferences and willingness to pay for service improvements: A stated choice analysis. Water Resource Research, 41, W02019.

Zwerina, K. (1997). Discrete choice experiments in marketing: Use of priors in efficient choice designs and their application to individual preference measurement. Heidelberg: Physica.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ian Bateman, Ali Chalak, Sergio Colombo, Scott Reid, Ken Willis, and participants at the EAERE conference for helpful comments on this work as well as two anonymous referees who considerably helped improve the paper. Excellent research assistance has been provided by Lawrie Harper-Simmonds. The research presented in this paper is based on a study undertaken for Thames Water Utilities Limited. The views expressed in this paper and any remaining errors are those of the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lanz, B., Provins, A. Using discrete choice experiments to regulate the provision of water services: do status quo choices reflect preferences?. J Regul Econ 47, 300–324 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-015-9272-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-015-9272-4

Keywords

- Cost-benefit analysis

- Regulated utilities

- Economic valuation

- Discrete choice experiments

- Individual decision making

- Status quo effect