Abstract

We examine the business groups’ risk-sharing hypothesis in the Japanese Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) market in which the unique external management system seems to be reinforcing power relationships among firms affiliated with the modern Japanese business groups, called keiretsu. We find that REITs whose sponsors belong to one of the keiretsu groups (keiretsu REITs) have significantly lower volatility of profitability than REITs whose sponsors do not belong to the keiretsu groups (non-keiretsu REITs). There is no significant difference in profitability between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs, controlling for firm and property characteristics. The abnormal portion of the profitability unexplained by firm characteristics is also significantly lower with keiretsu REITs. We also find that the keiretsu affiliation reduces the systematic volatility of affiliated REITs, while such an effect is not observed with the idiosyncratic volatility, suggesting that the risk-sharing effect may be beneficial for the value of REITs. Using the difference-in-differences design with propensity score matching, we find that the negative impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on the profitability was significantly smaller with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. Keiretsu REITs were also able to stabilize their capital structure by shifting some short-term debts to long-term debts without increasing the cost of loans under the uncertain situation caused by the Earthquake. Keiretsu REITs were able to borrow money from their affiliated group banks even right after the earthquake, while non-keiretsu REITs seem to have struggled to secure loans from those banks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Business groups that share a common historical background, or are linked to their governments, are often observed in Asian and Latin American countries such as Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, India, Singapore, China, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. The corporate finance literature has documented the effects of business groups on corporate structure and financial performance (Khanna & Rivkin, 2000; Bertrand et al., 2002; Khanna & Yafeh, 2005; Claessens et al., 2006; Almeida & Wolfenzon, 2006; Carney et al., 2011; Byun et al., 2013; Gaur et al., 2014; Mahmood et al., 2017).Footnote 1

In this study, we examine the effects of business group affiliation on business performance focusing on the Real Estate Investment Trusts in Japan (J-REITs) with the expectation that business groups still play important roles for J-REITs mainly because of their unique external management system, which seems to have reinforced the power relationships within the modern Japanese business groups.

Risk-sharing is one of the most significant effects of business group affiliation on the business operations of its member firms (Yafeh, 2003). The risk-sharing hypothesis posits that business groups enable member firms to share risks by smoothing income flows and reallocating money from one affiliate to another (Aoki, 1988). Member firms try to rescue other member firms when they are in trouble, while such firms might also exploit other members, for example, by receiving a premium for intra-group transactions (e.g. sale of real estate properties and lending). In this way, business group affiliation provides mutual insurance arrangements among member firms, especially when a firm’s access to highly developed capital markets is limited. Member firms thus try to ensure stable growth as a group in the long run through mutual insurance arrangements. Because of this risk-sharing behavior, member firms are expected to have lower variance in operating profitability, while member firms may not enjoy higher profitability or may even have lower profitability, compared with firms not affiliated with major business groups.

The empirical evidence from the literature suggests that the variance in operating profitability and growth rates is generally lower for business group-affiliated companies than for unaffiliated firms. The evidence also shows that profitability itself is lower for business group-affiliated companies than for unaffiliated firms, although the difference in profitability is often statistically insignificant (Nakatani, 1984; Ferris et al., 2003; Yafeh, 2003; Khanna & Yafeh, 2005; Chen et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2013).

As a result of a decrease in stable shareholding within business groups and a general move toward a more market-based financial system, the significance of business groups is reported to have weakened over time, for example, in the Japanese economy (Khanna & Yafeh, 2005).Footnote 2 However, we argue that the introduction of the REIT market in Japan has reemphasized the importance of business groups among firms affiliated with REITs. Kim et al. (2004) propose that although the keiretsu system entails the risk-sharing benefits, it is unlikely that these benefits accrue equally to all the members. They argue that keiretsu member firms possessing stronger power in their keiretsu are able to place more emphasis on growth in pursuing product and international diversification, whereas less powerful keiretsu members are subject to strong monitoring and emphasize stable profitability. The introduction of the REIT market might have reinforced this power relationship into the modern Japanese keiretsu groups and, as a result, the risk-sharing effect should be strongly evident among REITs, because REITs, as less powerful keiretsu members, should emphasize stable profitability instead of growth. Regardless of the weakening significance of business groups along with the economic development and modernization in many countries, it does seem possible that business groups still play important roles for REITs, especially those in Asian and Latin American countries, for several reasons.

First, REITs in these countries are managed by external asset management companies.Footnote 3 As summarized in Fig. 1, a REIT asset management company selects properties, executes investment strategies, and hires property managers to handle the leasing, management, maintenance, and operational aspects of properties owned by a REIT. In return, the REIT pays asset management fees to the asset management company. In this structure, both the asset management company and the property management company are usually wholly or partly owned by a REIT sponsor. A REIT sponsor is a large company that develops and/or manages commercial real estate properties.Footnote 4 A REIT sponsor is an entity that sources the properties placed into the REIT at the time of the initial public offering (IPO).Footnote 5 Thus, the external management structure of REITs naturally strengthens the control of the sponsor over the whole process of REIT management, potentially enhancing the power relationship within keiretsu groups if REIT sponsors belong to keiretsu groups. Therefore, whether or not a sponsor belongs to a business group should have a significant effect on the business operation of an externally managed REIT (e.g. in property acquisition, leasing arrangements, and debt financing), especially on the stability of profitability of REITs, since REITs, if affiliated with keiretsu groups, are placed as less powerful members of keiretsu groups.Footnote 6,Footnote 7

Second, many Asian and Latin American REIT markets began in the early 2000s,Footnote 8 and most of them are yet young and small, and only a few have credit ratings from S&P and/or Moody’s. REITs, therefore, have limited access to public capital markets and often have to rely heavily on bank loans. The relationships with banks (through a direct relationship or via a REIT sponsor) will also affect the REITs’ corporate financing decisions.Footnote 9 This further highlights the importance of business group affiliation of REIT sponsors, because major banks are also commonly affiliated with business groups and this business group affiliation translates into an excellent relationship with banks. In summary, the unique external management system and immaturity of Asian and Latin American REITs warrants a reexamination of the effects of business group affiliation on the financial performance of REITs.

The main purpose of this study is to test the business group risk-sharing hypothesis with J-REITs based on the assertion that the introduction of the REIT market in Japan has reemphasized the importance of business groups among firms affiliated with REITs. In Japan, we can still observe groups of independently managed firms, called keiretsu, that used to be family-owned conglomerates, called zaibatsu, before the end of World War II.Footnote 10 Some J-REITs have sponsors who belong to keiretsu groups (defined as keiretsu REITs), while others’ sponsors do not belong to any keiretsu groups (defined as non-keiretsu REITs). Because J-REITs adopt the external management system and the J-REIT market is still at the growth stage, we expect that whether or not a sponsor is affiliated with a keiretsu group should have significant effects on the financial performance of a J-REIT. Testing the risk-sharing hypothesis with J-REITs is especially interesting because a weakening effect of the keiretsu groups on general corporations in Japan has also been reported. The unique external management system and immaturity of the J-REIT market might have enhanced the power relationships within keiretsu groups to which some REIT sponsors belong. More specifically, we test if the volatility of operating profitability of keiretsu REITs is significantly lower than that of non-keiretsu REITs. In addition to the simple test of the volatility of operating profitability, we also compare the abnormal profits and the REIT stock return volatility between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs. Finally, we examine how keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs responded to an external shock focusing on its impacts on profitability and capital structure.

This study contributes to the corporate finance literature by showing the case in which business group affiliation still plays an important role even in a country where the significance of business group has generally weakened. Although prior studies (e.g., Ferris et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2013,) have shown the evidence of risk-sharing effect with general corporations, our study is the first to test the risk-sharing hypothesis considering the effect of the management system on the power relationships among keiretsu members. This study contributes to the REIT literature by adding a new perspective on the current discussion of the external management system for REITs. By linking business group affiliation with the external management system of REITs, this study attempts to reveal a situation where the external management system might bring benefits to REITs. Newer REIT markets have been developing in countries such as Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Singapore, South Korea, and ThailandFootnote 11 where business groups are observed and most REITs are (or expected to be) externally managed. The examination of the potential effects of business group affiliation on the operation of REITs is thus of global importance.

First, we find that Japanese REITs, whose sponsors belong to one of the 6 major keiretsu groups, have significantly lower volatility of profitability than REITs whose sponsors do not belong to any of the major keiretsu groups, even after controlling for firm and property characteristics. On the other hand, there is no significant difference in profitability between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs with the same controls. Secondly, focusing on the abnormal portion of profitability, we find that the portion of profitability unexplained by firm characteristics (conditional variance of profitability) is significantly lower with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. Thirdly, we find that the keiretsu affiliation reduces the systematic volatility of affiliated REITs compared with non-affiliated REITs, while it does not affect the idiosyncratic volatility, the result contrary to the finding of Chen et al. (2010) with general corporations. The systematic volatility of keiretsu REITs was significantly reduced compared with that of non-keiretsu REITs, especially when the J-REIT market experienced poor conditions, implying that when REITs are in trouble, keiretsu REITs may receive supports from firms in other industries in the affiliated keiretsu groups. Finally, we find that keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs, which share similar firm and property characteristics, responded quite differently to the exogenous shock (the Great East Japan Earthquake): the negative impact of the earthquake on profitability was significantly smaller with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. Keiretsu REITs were also able to stabilize their capital structure by shifting some short-term debts to long-term debts without increasing the cost of loans under the uncertain situation caused by the earthquake. It is also evident that keiretsu REITs were still able to borrow money from their affiliated group banks even right after the earthquake. On the other hand, non-keiretsu REITs seem to have struggled to secure loans from these keiretsu banks after the earthquake.

Zaibatsu and Keiretsu in Japan

Introduction

The Japanese term “keiretsu” is widely recognized in the corporate finance literature. It refers to clusters of independently managed firms that used to be family-owned conglomerates called zaibatsu before the end of World War II. A zaibatsu is a family-run conglomerate (multi-layered and industrially diversified business entity), controlled by a singular holding company structure and owned by families and/or clans of wealthy Japanese (Lincoln & Shimotani, 2009). The formation of zaibatsu groups started in the late 1800s, while zaibatsu became a popular term in the late 1920s. In the zaibatsu structure, the holding company was the overwhelmingly largest shareholder of the member companies and the member companies held more than half of the holding company’s stock. The stock shares of members were rarely sold by other members to third parties. Under this structure, zaibatsu drove the finance, heavy industry, and shipping sectors that led Japan’s economy. It is reported that in 1930, 4 large zaibatsu groups (Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, Yasuda, and Mitsui) controlled approximately 75% of Japan’s economy GDP (Kensy, 2001). After World War II, the American occupational forces decided to dissolve the zaibatsu, claiming that the groups were responsible for the war through the close connection between their group subsidiaries in heavy industry and the Imperial Japanese Army. Shares owned by controlling families of zaibatsu were confiscated and sold to individuals.Footnote 12

However, after the Tokyo Stock Exchange reopened in 1949, former leading member companies of the zaibatsu, especially banks, eventually started buying shares of former member companies from individuals to form informal groups, marking the beginning of postwar keiretsu. Today, six large keiretsu groups exist, each of which has a large commercial bank as a general coordinator of its group: Mitsubishi (Kinyo-kai), Sumitomo (Hakusui-kai), Mitsui (Nimoku-kai), Fuyo (Fuyo-kai), the former Dai-ichi Kangyo (Sankin-kai), and Sanwa (Sansui-kai).Footnote 13 Approximately 20–40 companies from various industries belong to each of these 6 keiretsu groups, some of which are sponsors of J-REITs. In the 1990s, firms associated with the largest 6 keiretsu groups, which represented only 0.007% of the total number of all Japanese firms, accounted for approximately 4% of employment, 13% of assets, 15% of capital, 14% of sales, and 12% of profits (Peng et al., 2001). An important governance structure associated with keiretsu is the President’s Council (shacho-kai), which is now considered an informal Executive Committee wherein the main bank typically hosts monthly meetings to strengthen the connection among the group members and share information within the group.

Some of the anecdotal evidence suggests that the keiretsu system is an important aspect of the corporate governance of J-REITs. Indeed, 23 of the 75 J-REITs in our study sample have sponsors from one of the 6 major keiretsu groups for the study period from 2004 to 2018. During the global financial crisis, 1 J-REIT (New City Residence, non-Keiretsu REIT) filed for bankruptcy in 2008, and 8 J-REITs (all non-keiretsu J-REITs) experienced changes in their sponsors from 2008 to 2010, due to the bankruptcy or financial difficulty of their original sponsors. None of the J-REITs with keiretsu sponsors (keiretsu REITs) experienced bankruptcy or any change in their sponsors.

Theories of Effects of Keiretsu System

Researchers have proposed theories that explain the potential benefits of keiretsu affiliation mainly from three perspectives: governance perspective, internal market perspective, and power-dependence perspective. First, Aoki (1994) and Berglof and Perotti (1994) propose that keiretsu systems represent an effective corporate governance structure and monitoring mechanism that can mitigate incentive, information, and control problems associated with agency conflicts. In the typical keiretsu system, the main bank is usually the largest lender and holds substantial equity stakes in the member firms. With significant stakes as both a shareholder and a debt holder, the main bank has a strong incentive to monitor group members closely to safeguard its own interests as both a lender and an equity holder, thus mitigating agency conflicts. The main bank can maintain a legal maximum of only 5% ownership in a member firm. However, extensive cross-ownership within the keiretsu group allows the main bank to mobilize shareholdings of other member firms for concerted voting, constituting a collective enforcement mechanism (Berglof & Perotti, 1994).

Secondly, the keiretsu group performs the role of an internal market resource allocator (Khanna & Palepu, 1997, 2000a, 2000b). Keiretsu member firms from every major industrial sector prefer to transact with one another on a long-term basis than with outside firms, engaging in extensive internal purchasing and selling of goods and services (Gerlach, 1992). Since a keiretsu group usually includes members in all the major sectors, the keiretsu can provide a broad scope of benefits especially when and where market mechanisms are less functional (e.g., in developing countries and under economic crises). Therefore, keiretsu member firms can mobilize resources embedded in a web of relationships in the keiretsu, creating group-based resource allocation advantages over independent firms that do not belong to keiretsu groups.

Thirdly, Kim et al. (2004) propose that although the keiretsu system entails governance and internal market benefits, it is unlikely that these benefits accrue equally to all the member firms because embedded power-dependence relationships within a keiretsu represent a potential factor in the relative appropriation of group affiliation benefits. Instead, keiretsu member firms possessing stronger power in their keiretsu are able to place more emphasis on growth in pursuing product and international diversification, whereas less powerful keiretsu members are subject to strong monitoring and emphasize stable profitability. We argue that REITs in Japan are typical examples of less powerful keiretsu members subject to strong monitoring from more powerful member firms such as the main banks and REIT sponsors because of their external management system. As a result, we expect that the risk-sharing effect is clearer among REITs than among general corporations, because REITs, as less powerful keiretsu members, should emphasize stable profitability instead of growth potential.

Data and Methodology

Data

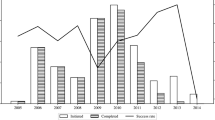

Our study period runs from January 2004 to December 2018. Although the first 2 J-REITs were listed in 2001, the number of J-REITs and their market size started to increase after 2004. Thus, we begin our analysis in that year. The number of J-REITs increased to 42 in 2007, decreased to 34 as of November 2011 as a result of bankruptcies and mergers, and kept increasing up to 61 as of December 2018. In our final study sample, there are 75 unique J-REITs, including ones that were delisted during the study period for some reason (e.g. bankruptcy of sponsor, change of sponsor, or merger). The list of J-REITs along with the information on their sponsors is provided in Appendix 1.

We identify REIT sponsors using information taken from the websites of the J-REITs and their asset management companies. We identify the keiretsu sponsors using several sources, including Industrial Grouping in Japan (GJ) published by Dodwell Marketing Consultants. Corporate data are taken from S&P Global Market Intelligence (formerly SNL), DATASTREAM, and companies’ semi-annual reports.Footnote 14 Among 75 REITs, 23 have sponsors that belong to one of the 6 keiretsu groups (keiretsu REITs), and 52 have sponsors that do not belong to any keiretsu group (non-keiretsu REITs).

Volatility of Profitability and Profitability

We begin with a simple test of the risk-sharing hypothesis that, compared with non-keiretsu REITs, keiretsu REITs are expected to have lower variance in operating profitability (Eq. (1)), while keiretsu REITs may not enjoy higher profitability or may even have lower profitability (Eq. (2)):

where vFFOAi is the standard deviation of each REIT’s funds from operations (FFO)Footnote 15 divided by each REIT’s total assets calculated over all years for which we have data.Footnote 16,Footnote 17 Keiretsui is the dummy variable that takes the value of one for REITs whose sponsors are affiliated with keiretsu groups and the value of zero otherwise. Sizei is the log of market capitalization, Sizei2 is the quadratic term of the centered size variable, FFOAi is the funds from operations divided by total assets, REITAgei is the number of years since each REIT’s initial public offering date, LTVi is the loan-to-value ratio, PropAgei is the average age of properties, and OccuRatei is the average occupancy rate of REITi. Equation (1) is a cross-sectional regression where all control variables are the averages over all years for which we have data for each REIT. Since the standard deviation of profit is calculated based on the time series of different lengths for different REITs, the standard deviation of the error term may not be constant over all observations. Therefore, we adopt the method of weighted least squares where we use the number of observations per REIT as weights assuming that the number of observations reflects the amount of the information contained in the standard deviation of profit of each REIT to maximize the efficiency of parameter estimation. Equation (2) is an unbalanced panel regression where all control variables are the values for each half-year period for each REIT.

Conditional Variance of Profitability

This test focuses on the possible risk-sharing in which keiretsu REITs receive support from other firms in the affiliated groups when their profitability is lower than usual, while REITs assist other group firms when REITs’ profitability is above normal. We first regress profitability on size, half-year, and REIT-fixed effects, which capture all time-invariant REIT attributes including keiretsu affiliation. We then test whether unexplained changes in profitability, which are deviations from the regression line, are smaller for keiretsu REITs than for non-keiretsu REITs, by regressing the squared residuals from the first regression (i.e. the conditional variance of profitability) on the keiretsu dummy and control variables (size, the quadratic term of size, the ratio of FFO to total assets, REIT age, loan-to-value ratio, the age of properties, the occupancy rate, and half-year fixed effects).

Stock Return Volatility

While the risk-sharing hypothesis is associated with the effect of keiretsu affiliation on variance in operating profitability of REITs, we also examine if the same effect is evident from the shareholders’ perspective by using the volatility of each REITs’ share price total returns as a dependent variable for three reasons. First, the use of the share price information allows us to conduct panel-based analyses, although measuring variance in operating profitability prevents us from conducting such analyses. Secondly, we are able to examine if and how keiretsu affiliation is perceived by REITs’ shareholders. Thirdly, we are able to examine if the effect of keiretsu affiliation is more meaningful among REITs than among general corporations, as we hypothesize, especially because we conduct this part of the analyses by decomposing the total volatility into the idiosyncratic volatility and the systematic volatility. By testing the risk-sharing hypothesis with the general corporations in Japan, Chen et al. (2010) found that the risk-sharing among keiretsu firms reduces the idiosyncratic risk but increases the market-level systematic risk. Since it is the systematic risk, not the idiosyncratic risk, that is priced (i.e., important for well-diversified investors), this result suggests that the risk-sharing among keiretsu firms may actually have a detrimental effect on the value of keiretsu firms. However, we argue that the risk-sharing among keiretsu REITs should have a beneficial effect on the value of keiretsu REITs, because the benefits of keiretsu affiliation are amplified by the external management system of REITs as we explained earlier. The analyses based on the decomposition of REIT stock volatility shed light on this assertion.

We measure the idiosyncratic volatility and the systematic volatility based on the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) as follows:

where Rit is the excess return on REIT i on day t. MKTt is the excess return on the Japanese REIT index on day t. Total volatility of REIT i is measured by the standard deviation of Rit, denoted by σi. The idiosyncratic volatility of REIT i is proxied by the standard deviation of εit in Eq. (3), denoted by σε, i. σε, i is estimated by running 3-month rolling regressions following Eq. (3). The systematic volatility of REIT i is defined as the difference between total and idiosyncratic volatility, σS, i = σi − σε, i. These volatilities are measured for each half-year period based on the daily total returns and are annualized. Then, to test the risk-sharing hypothesis based on the stock return volatility, we run the following panel regressions for the idiosyncratic volatility (Eq. (4)) and the systematic volatility (Eq. (5)) where hy represents each half-year period:

Response of Profitability to Exogenous Shock

The purpose of this test is to examine if keiretsu groups assist member firms (i.e. keiretsu REITs) that are subject to an exogenous shock, by examining the possible difference in the impact of the exogenous shock on the profitability between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs.

We choose the Great East Japan Earthquake, the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan and the fourth most powerful earthquake in the world, as a shock that is purely exogenous and has affected REITs’ profitability directly and indirectly. The earthquake was a magnitude 9.0 undersea megathrust earthquake and happened at 14:46 on March 11, 2011. The epicenter was approximately 43 miles east of the Oshika Peninsula of the Tohoku region, which is approximately 230 miles from the center of Tokyo, and the hypocenter was at an underwater depth of approximately 18 miles. In terms of the seismic intensity (SI) level,Footnote 18 the Tohoku area near the epicenter experienced SI:7 and the areas within Tokyo experienced SI:5+ or SI:5–. The earthquake was followed by tsunami waves and resulted in 15,897 deaths and 2534 people missing according to the Japanese National Police Agency, confirmed as of December 2018. The tsunami waves also caused nuclear accidents (level 7 meltdowns) at three reactors in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant complex, which is approximately 137 miles from the center of Tokyo. As a result, residents within a 12-mile radius of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant and a 6.2-mile radius of the Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant were evacuated. The economic loss of the earthquake was estimated to be US$ 235 billion according to the World Bank.

While Japanese REITs did not own many properties within the proximity of the epicenter and none of the REITs’ properties were severely damaged, the profitability of REITs was affected by the earthquake. For example, the earthquake caused minor physical damage to some REITs’ properties in Tokyo and other big cities, forced REITs to implement additional seismic assessments and upgrade their earthquake insurance, or led some tenants to move to properties that were more robust against earthquakes. Keiretsu REITs might have enjoyed preferential pricing with property transactions, repairing works, or financing via member firms in different industries, while such “rescue” arrangements might not have been available for non-keiretsu REITs. As a result, the negative effect of the earthquake could be significantly smaller among keiretsu REITs than among non-keiretsu REITs.

For this test, it is essential to examine the impact difference due to keiretsu affiliation while controlling for the strength of properties against earthquakes along with other control variables. J-REIT publishes, in its semi-annual financial reports, an earthquake risk measure called Probable Maximum Loss (PML), assessed by a third party with expert knowledge for each property it holds as well as for the whole portfolio. The PML is reported as the ratio of the expected physical loss amount as a proportion of the building’s replacement costs, corresponding to the kind of huge earthquake that could happen once every 475 years (i.e. 10% probability of occurrence in 50 years). The PML is calculated based on factors such as a building’s earthquake resistance, soil environment, earthquake history of a location, and proximity to an active fault. The portfolio PML for a REIT is calculated also considering the geographical diversification of its properties. We hand-collected the published portfolio PML of each REIT from semi-annual financial reports.

We select the closest match among non-keiretsu REIT for each keiretsu REIT focusing on portfolio PML and other variables that seem to affect the impact of the earthquake on profitability (size, loan-to-value ratio, occupancy rate, and the proportion of properties in Tokyo) based on the data during the pre-event period between the second half of 2009 and the second half of 2010.Footnote 19 We use one-to-one matching with the closest propensity score to improve covariate balance and reduce bias. Using the matched sample, we employ a difference-in-differences (DID) analysis. This technique calculates the effect of a treatment on a treatment group versus a control group. To examine the effect of the earthquake on REITs’ profitability, there are two treatment effects: keiretsu with mutual insurance arrangements versus non-keiretsu without mutual insurance arrangements and before versus after the earthquake. The effect of these treatments is analyzed as follows:

where FFOAit is the funds from operations divided by total assets for each REITi at a semi-annual period of t. Postit is the dummy variable that takes the value of one for the post-event period during the first half of 2011 and the second half of 2011 and the value of zero for the pre-event period during the second half of 2009 and the second half of 2010. Keiretsui is the dummy variable that takes the value of one for REITs whose sponsors are affiliated with keiretsu groups and the value of zero otherwise. β2 is the DID estimator and the parameter of interest.Footnote 20

Results

Summary Statistics

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of 75 REITs (23 keiretsu REITs and 52 non-keiretsu REITs) for the overall period. First, the volatility of profitability is significantly lower with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. The volatility of profitability of keiretsu REITs is only about 60% of that of non-keiretsu REITs, measured both by FFO/Asset and ROA. The profitability itself is significantly higher with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs when measured by FFO/Asset, while there is no significant difference when measured by ROA. The smoother profitability observed with keiretsu REITs implies the existence of the risk-sharing of the business group affiliation, while the lower profitability, often observed with general corporations affiliated with business groups (e.g., see Table 3 in Yafeh, 2003), is not evident with keiretsu REITs.

Although smoother profitability is observed with keiretsu REITs, it may be the result of differences in firm and property characteristics between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs.Footnote 21 For example, compared with non-keiretsu REITs, keiretsu REITs tend to exhibit higher firm value (or growth opportunity) measured by Tobin’s Q, higher market capitalization, lower dividend yield, lower leverage, lower loan cost, and be older. Keiretsu REITs own properties with a larger leasable area, higher occupancy rate, and lower PML (i.e. stronger against earthquakes) compared with properties owned by non-keiretsu REITs. The property portfolios of Keiretsu REITs consist more of office, retail, and logistics properties and less of residential properties. Properties owned by keiretsu REITs are more concentrated in the big 3 cities (Tokyo 23 wards, Osaka, and Nagoya). Shares of keiretsu REITs are held more by financial institutions and less by individuals, non-financial institutions, and foreign investors compared with shares of non-keiretsu REITs.

Test of Volatility of Profitability and Profitability

Table 2 summarizes the results of the regressions that examine the impact of keiretsu affiliation on the volatility of profitability and profitability. In Panel A, a dependent variable is the standard deviation of the ratio of FFO to total assets (VFFOA), as shown in Eq. (1). In Panel B, a dependent variable is the ratio of FFO to total assets (FFOA), as shown in Eq. (2). The risk-sharing hypothesis suggests that keiretsu REITs are expected to have lower variance in operating profitability, while keiretsu REITs may not enjoy higher profitability or may even have lower profitability, compared with REITs not affiliated with major keiretsu groups.

Panel A shows that REITs whose sponsors belong to one of the 6 major keiretsu groups have significantly lower volatility of profitability than REITs whose sponsors do not belong to any of the major keiretsu groups. This keiretsu affiliation effect is still significant at the 5% level even after controlling for firm and property characteristics (Models 2 and 3). Based on Model 3, the result shows that if a REIT has a keiretsu sponsor, the volatility of profitability is reduced by 0.46%, which is 30% of the average volatility of profitability among non-keiretsu REITs (1.51%) as shown in Table 1, keeping other variables constant. This result implies that a keiretsu REIT indeed enjoys the mutual insurance of keiretsu group affiliation by having a keiretsu member firm as its sponsor.

Panel B of Table 2 shows that keiretsu REITs have significantly higher (by 0.27%) profits than non-keiretsu REITs without control variables (Model 1). However, after adding firm and property characteristics control variables, this effect disappears and there is no significant difference in profitability between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs. This result in Panel B suggests that the higher profitability observed with keiretsu REITs is coming not from their sponsors’ affiliation with keiretsu groups, but from the firm and property characteristics of keiretsu REITs, such as larger size, lower LTV, newer properties, and higher occupancy rates. Earlier studies suggest that the effect of business group affiliation on profitability itself is often insignificant, or even negative, which is consistent with the result we obtain with J-REITs.

While the results with both standard deviation (volatility) and the mean of profitability seem to support the risk-sharing hypothesis, a difference in profitability between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs is significant with the tails (abnormal portion) of profitability distribution as shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2 shows that the skewness of non-keiretsu REITs (−3.07) is much lower (i.e. more negatively skewed) than that of keiretsu REITs (−0.01) and the kurtosis of non-keiretsu REITs (50.58) is much higher than that of keiretsu REITs (11.94). A two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test rejects the equal distribution hypothesis (p = 0.000). It thus seems important to examine the profitability difference between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs, focusing on the tail portions of the distribution. The following analyses examine the abnormal profits and the response to an external shock to profitability, comparing those between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs.

Test of Conditional Variance of Profitability

Keiretsu REITs may receive support from other firms in the affiliated group (thanks to their sponsors’ affiliation), especially when their profitability is lower than usual, while REITs may assist other group firms when REITs’ profitability is above normal. To test this implication, in the regressions summarized in Table 3, a dependent variable is the squared residual from the regression (i.e. conditional variance of profitability) in which a dependent variable is the profitability (FFOA) and independent variables are size, half-year, and REIT-fixed effects.

The results show that the conditional variance of profitability is significantly lower with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs, even with firm and property characteristics controls as well as half-year fixed effects (Model 3). This result implies that keiretsu REITs may be considered as sub-members of keiretsu groups and keiretsu REITs are part of mutual insurance arrangements by which member firms rescue other member firms (are rescued by other member firms) when they experience unexpected positive (negative) surprises that affect profitability. The result is consistent with the observation in Fig. 2 that the tails of the profitability distribution are much thinner with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs.

We also examine if the degree of the reduction of the conditional variance of profitability differs among keiretsu REITs based on shareholders’ composition (i.e. proportions of shares held by individuals, financial institutions, non-financial institutions, and foreign investors) by including the interaction term between a shareholding variable and keiretsu dummy along with other variances in each regression. We find that the proportion of shares held by non-financial (domestic) institutions is the only shareholding variable that affects, to some extent, the degree of the reduction of conditional variance of profitability among keiretsu REITs: among keiretsu REITs, if shares are held more by non-financial institutions, those keiretsu REITs exhibit even lower (B = –0.17; p = 0.087) conditional variance of profitability, suggesting that they enjoy a greater keiretsu affiliation mutual insurance effect. If more shares of a keiretsu REIT are held by domestic non-financial institutions, the chance that some of these institutions are also members of the same keiretsu group may be higher. Such a keiretsu REIT may therefore enjoy a stronger mutual insurance agreement effect through these group members/shareholders.

Test of Stock Return Volatility

Table 4 summarizes the results of the panel regressions that examine if the keiretsu’s risk-sharing effect is evident from the shareholders’ perspective by using the volatility of each REITs’ share price total returns as a dependent variable. Panel A shows the descriptive statistics, Panel B shows the results of the regressions where a dependent variable is the idiosyncratic volatility, and Panel C is for the results of the regressions where a dependent variable is the systematic volatility.

First of all, with the overall period, the risk-sharing effect of keiretsu is not evident with the idiosyncratic volatility (Panel B), while it is evident with the systematic volatility (Panel C), even after controlling for firm and property characteristics as well as year fixed effects. This result is opposite to the result found by Chen et al. (2010) with general corporations. Chen et al. (2010) found that the idiosyncratic volatility is reduced due to the risk-sharing of keiretsu, while the systematic volatility increases among keiretsu-affiliated general corporations. The results of Chen et al. (2010) suggest that risk-sharing of keiretsu may deteriorate the value of the firms because the idiosyncratic volatility anyway becomes insignificant for well-diversified investors and the systematic volatility is priced and important for such investors. To the contrary, we found that the systematic volatility is significantly smaller among keiretsu REITs than non-keiretsu REITs, while there is no significant difference in the idiosyncratic volatility regardless of the keiretsu affiliation of REITs. This result suggests that the risk-sharing of keiretsu may bring more benefits than harm to Japanese REITs.

The results in Panel B and C are also shown for different conditions of the J-REIT market. Up market is defined as the periods when the overall J-REIT market experienced positive returns and Down market is defined as the periods when the overall J-REIT market experienced negative returns. Panel C clearly shows that the systematic volatility of keiretsu REITs was significantly reduced compared with that of non-keiretsu REITs, especially when the J-REIT market experienced poor conditions (Down market). This result implies that when REITs are in trouble, keiretsu REITs may receive supports from firms in other industries in the affiliated keiretsu groups.

The examination of the effects of risk-sharing of keiretsu focusing on the idiosyncratic volatility and the systematic volatility suggests that the risk-sharing effect may be beneficial for the value of REITs, while it may deteriorate the value of general corporations. We argue that this stark and important difference of the effect comes from the external management system of REITs. This result is important because it suggests that there is a certain governance structure in which business group affiliation results in more benefits than harm. In addition, the result emphasizes the importance of the consideration of cultural factors including the existence of business groups when discussing the suitable management structure (i.e., internal vs. external) for newly developing REIT markets in different countries.

Response of Profitability to Exogenous Shock

To test the risk-sharing hypothesis focusing on abnormal profitability further, we examine if keiretsu group affiliation of sponsors affects the profitability of REITs that are subject to an exogenous shock. As a shock that is purely exogenous and has affected REITs’ profitability, we use the Great East Japan Earthquake. Figure 3 compares the profitability of keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs before matching for the overall study period. It shows that the Great East Japan Earthquake negatively affected the profitability of REITs in general, especially in the first half of 2011, and that the negative impact was much smaller with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. However, this observation based on the unmatched sample may be simply a result of differences in firm and property characteristics between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs. We, therefore, examine the possible difference in the impact of the exogenous shock on the profitability between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs, focusing on the matched pairs of keiretsu REIT and non-keiretsu REIT that share similar firm and property characteristics.

Table 5 shows the quality of the matched sample of 30 REITs (15 keiretsu REITs and 15 non-keiretsu REITs) in Panel A and summarizes the statistics of the profitability variables in Panel B. Panel A confirms that, as a result of matching, our treatment group (keiretsu REITs) and the comparison group (non-keiretsu REITs) are highly homogeneous with respect to size, LTV, occupancy rate, PML, and the proportion of properties owned in Tokyo. The mean differences of these variables were reduced by 41%–97%. Furthermore, all variables satisfy Cochran’s rule of thumb. This means that none of these variables differs by more than a quarter of a standard deviation of the respective variable between the treatment and comparison groups, suggesting that our matched sample is well balanced (Cochran, 1968; Ho et al., 2007).Footnote 22 Therefore, we have a panel of reasonably balanced treatment and comparison REITs, which allows us to claim that any observed treatment effect on profitability is not biased by differences between treatment and comparison groups in firm and property characteristics. In Panel B of Table 5, it is notable that, even in the matched sample, the volatilities of FFO ratio and ROA are still much lower among keiretsu REITs than among non-keiretsu REITs, which again seems to support the risk-sharing hypothesis of business group affiliation.

Table 6 summarizes the result of the difference-in-differences (DID) regression based on the matched sample of 15 keiretsu REITs and 15 non-keiretsu REITs. A dependent variable is the ratio of FFO to total assets (annualized and multiplied by 100). The pre-event period is from the second half of 2009 to the second half of 2010. The post-event period is from the first half of 2011 to the second half of 2011. A coefficient for Time#Keiretsu is the DID estimator and the parameter of interest. Figure 4 compares the profitability of keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs in the matched sample for the overall study period. It first shows that the profitability of keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs has been more similar to each other in the matched sample compared with the trend observed with the unmatched sample, as shown in Fig. 3, which further verifies the quality of matching and seems to support the parallel trend assumption in the pre-event period. However, even within the matched sample, the negative impact of the earthquake is much larger with non-keiretsu REITs than with keiretsu REITs.

In Table 6, the DID estimator shows a significantly large positive effect (B = 1.09; z = 2.60), suggesting that while the earthquake negatively affected both keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs, this negative impact was much smaller with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. As the coefficient of the Time variable shows, the earthquake reduced the profitability of non-keiretsu REITs by 1.4%, while the DID estimator shows that the negative effect with keiretsu REITs was smaller than the negative effect with non-keiretsu REITs by 1.1%. Thus, keiretsu REITs were, in fact, not greatly affected by the Earthquake. Since we conduct the DID analysis with the matched sample, the result suggests that the mutual insurance of keiretsu group affiliation played some role in absorbing the shock to the profitability of keiretsu REITs.

Although understanding the detailed mechanism of the risk-sharing of keiretsu group affiliation is beyond the scope of this study, we run analyses to gain insights for future study, focusing on the change in the capital structure after the Great East Japan Earthquake. During crisis periods, REITs can easily have a liquidity issue because they are not allowed to retain a large amount of cash due to the distribution requirement. The liquidity issue in crisis periods is amplified if REITs rely heavily on short-term debt, because banks may not be willing or able to refinance this debt when banks are also in a difficult situation. REITs with liquidity problems may not be able to execute proper property management, including repairs and renovations, which may affect the long-term stability of profitability. Thus, the capital structure especially during crisis periods may be one of the mechanisms behind the observed risk-sharing effect of keiretsu group affiliation, because a keiretsu REIT may be able to receive preferential financing arrangements from a bank that is also a member of the same keiretsu group during crisis periods. To compare the change in the capital structure during crisis periods between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs, we run DID regressions similar to those in Table 6 with the same matched sample, using capital structure variables as dependent variables to examine what kind of differences in the capital structure can be observed between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs after the earthquake.

Panel A of Table 7 summarizes the results.Footnote 23 While there is no significant difference in the change in LTV between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs (Model 1), keiretsu REITs reduced the amount of short-term debt significantly more (Model 2) and increased the amount of long-term debt significantly more (Model 3), compared with these changes among non-keiretsu REITs during the crisis period. These results suggest that only keiretsu REITs were able to stabilize their capital structure to alleviate the liquidity concern when the earthquake created a greater amount of uncertainty in the Japanese economy. Furthermore, the result of Model 4 shows that keiretsu REITs stabilized their capital structure without having an excessively higher cost of debt compared with the cost of debt of non-keiretsu REITs, even though long-term debts usually carry higher costs of debt. While the investigation into more direct evidence is warranted, the results in Table 7 imply that keiretsu REITs may have received preferential financing arrangements from banks affiliated with the same keiretsu groups after the earthquake that may have affected the long-term stability of their profitability.

To deepen the understanding of the possible mechanism in which how keiretsu affiliation can reduce the volatility of profitability further, Panel B of Table 7 summarizes the statistics of the new loans originated by banks affiliated with keiretsu groups for 15 keiretsu REITs and 15 non-keiretsu REITs in the matched sample.Footnote 24 For each keiretsu REIT, we summarize the loans from a bank affiliated with the same keiretsu group. For non-keiretsu REITs, we summarize loans from banks affiliated with any of 6 major keiretsu groups. Thus, the definition of keiretsu banks differs for keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs. Nevertheless, the results in Panel B are meaningful because our definition should work against our hypothesis that keiretsu REITs benefited more from keiretsu banks during the crisis period. Compared with the pre-earthquake period, the total amount of the loans originated by keiretsu banks for keiretsu REITs was reduced by 54% after the Great East Japan Earthquake, while this amount with non-keiretsu REITs was reduced by 92%,Footnote 25 indicating that keiretsu REITs were still able to borrow money from their affiliated group banks even right after the earthquake. On the other hand, non-keiretsu REITs seem to have struggled to secure loans from these keiretsu banks after the earthquake. It is also interesting to note that the new bank loans originated right after the earthquake for keiretsu REITs carried lower interest rates (0.478% vs. 0.763%) and longer maturities (54.22 days vs. 37.39 days) compared with loans made for non-keiretsu REITs. Thus, keiretsu banks seem to have prioritized their lending activities for REITs affiliated with the same keiretsu groups, which must have contributed to reducing the volatility of profitability of these keiretsu REITs.

Robustness Checks

First, different property types have different typical lease lengths and Table 2 shows that there are significant differences in the property portfolio composition between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs. Therefore, the reduced volatility of profitability may be attributable to the different property types that REITs hold. The degree of diversification in terms of property type may also affect the volatility of profitability. We test whether our estimation results are robust if we add property type variables along with the firm and property characteristic control variables already included. More specifically, based on Eq. (1) whose results are shown in Model 3 of Panel A in Table 2, we further add the average proportions of office, residential, retail, and logistics properties held by each REIT. Panel A of Appendix 2 confirms that the Keiretsu variable remains significant at the 10% level (B = −0.446; t = −1.74), while the addition of these property type variables increased the R-squared measure by 10%.

Secondly, we re-run our analyses again based on Eq. (1) using rolling 10-year periods (i.e. 20 half-year periods) to examine if the risk-sharing effect has been stable over time or period specific. In each regression, we also add property type variables. Panel B of Appendix 2 shows that the coefficient and the standard error are quite stable and that the expected negative effect of the Keiretsu variable is always significant at the 5% level, regardless of the estimation period.

Thirdly, to address any potential omitted variable concerns, we run the regression where a dependent variable is the volatility of FFO ratio (VFFOA) and an independent variable is the keiretsu dummy, using the matched sample of 15 keiretsu REITs and 15 non-keiretsu REITs, which were confirmed to be quite homogeneous in Table 5. We run the cross-sectional regression for the overall study period. Panel C of Appendix 2 shows that, even with the matched sample, the volatility of profitability is significantly lower among keiretsu REITs than among non-keiretsu REITs.

Finally, the important argument in this study is that the external management system of the J-REITs is unique and helps reinforce power relationships among firms affiliated with business groups. To support this argument, we examine the effect of the sponsor ownership of REITs’ shares on the relationship between the keiretsu affiliation and the volatility of profitability.Footnote 26 The average and the standard deviation of the sponsor ownership ratio among J-REITs in the sample are 10.29% and 9.22%, respectively. Specifically, we added the interaction term between keiretsu dummy variable and the sponsor ownership variable along with all the control variables to the regression (volatility regression) where a dependent variable is the volatility of FFO ratio (VFFOA) and to the regression where a dependent variable is the conditional variance of profitability (conditional variance regression). With the volatility regression, the interaction term is negative and significant at the 5% level (β = −0.45; t = −2.12). With the conditional variance regression, the interaction term is also negative and significant at the 10% level (β = −0.01; t = −1.65). These results suggest that when the relationship between sponsors and REITs is reinforced as evident with the higher sponsor ownership, the risk-sharing effect of keiretsu affiliation is indeed stronger resulting in the reduced volatility of profitability and the conditional variance of profitability.

Concluding Remarks

We examine the business groups’ risk-sharing hypothesis with Japanese REITs with the expectation that the business groups still play important roles for REITs even in a country where the significance of such groups is reported to have weakened with general corporations. We argue that this revival of the risk-sharing effect is caused mainly by the external management system of REITs, which reinforced the power relationship within the modern Japanese keiretsu groups.

First, we find that REITs, whose sponsors belong to one of the 6 major keiretsu groups, have significantly lower volatility of profitability than REITs whose sponsors do not belong to any of the major keiretsu groups, even after controlling for firm and property characteristics. On the other hand, there is no significant difference in profitability between keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs with the same controls. Secondly, focusing on abnormal profitability, we find that the portion of profitability unexplained by firm characteristics (conditional variance of profitability) is significantly lower with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. This result implies that keiretsu REITs may be considered as sub-members of keiretsu groups and keiretsu REITs are part of mutual insurance arrangements among keiretsu group member firms. Thirdly, we find that the keiretsu affiliation reduces the systematic volatility of affiliated REITs compared with non-affiliated REITs, while it does not affect the idiosyncratic volatility. Since it is the systematic volatility that is priced and important for well-diversified investors, the result suggests that the risk-sharing of keiretsu may bring more benefits than harm to Japanese REITs. The systematic volatility of keiretsu REITs is reduced especially when the J-REIT market experienced poor conditions, implying that when REITs are in trouble, keiretsu REITs may receive supports from firms in other industries that also belong to the affiliated keiretsu groups.

Finally, we find that keiretsu REITs and non-keiretsu REITs, which share the similar firm and property characteristics, responded quite differently to the exogenous shock (the Great East Japan Earthquake): the negative impact of the Earthquake on profitability was significantly smaller with keiretsu REITs than with non-keiretsu REITs. This result seems to suggest that the mutual insurance of keiretsu group affiliation played some role in absorbing the earthquake shock to the profitability of keiretsu REITs. Keiretsu REITs were also able to stabilize their capital structure by shifting some short-term debt to long-term debt without increasing the cost of loans, under the uncertain situation caused by the earthquake. The data also reveals that keiretsu REITs were still able to borrow money from their affiliated group banks even right after the earthquake. On the other hand, non-keiretsu REITs seem to have struggled to secure loans from these keiretsu banks after the earthquake.

The results of this study suggest that business group affiliation may have significant effects on REITs, especially when they are externally managed and are still at the developing stage. Such REIT markets are often observed in countries where business groups similar to Japanese keiretsu are also present, such as Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand. Thus, the examination of the potential effects of business group affiliation on profitability, management style, and impacts of economic shocks on REITs is of global importance.

Notes

More recently, the literature examined the effects of business groups on corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies and found that, in general, group affiliation is associated with higher CSR and that CSR works as a means of enhancing reputational capital to buffer any bad events, especially among group affiliated firms (Choi et al., 2018; Ray & Ray, 2018).

Khanna and Yafeh (2005) show that the effect of business group affiliation on profit volatility for the post-war period between 1984 and 1992 was about one-tenth of the effect observed for the pre-war period.

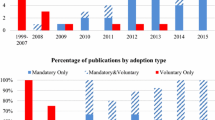

Based on market capitalization as of August 2017, the proportions of REITs managed externally in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia were only 3%, 9%, and 10%, respectively. In contrast, all existing REITs in Japan, Singapore, and Hong Kong are externally managed; all 8 REITs in Mexico are also externally managed. Internally managed REITs employ investment managers and support staff that manage the operations of the company’s day-to-day activities without outsourcing asset management tasks to an external management company.

Examples of REIT sponsors include real estate developers, real estate service companies, retail companies, financial service companies, and trading companies.

REITs with this structure are sometimes called captive REITs.

In the United States, the external management system of REIT was almost proven to be worse than the internal management system, because it faced greater agency cost due to sponsor–shareholder relationship, and earlier studies found that the performance of externally-managed REITs tended to be worse than that of internally-managed REITs (Hsieh & Sirmans, 1991; Cannon & Vogt, 1995; Wei et al., 1995; Capozza & Seguin, 2000). However, more recent studies showed the benefits of an external management system for Asian REITs (Wong et al., 2013; Downs et al., 2016; Li & Chuen, 2018).

If a REIT is managed internally, it is difficult for any single company to have a dominant influence over its management of the REIT because of the ownership requirements of REITs.

The first REITs were listed in Japan, Singapore, and Hong Kong in 2001, 2002, and 2005, respectively. The first REIT in India was listed in 2019 and it is reported that China is in the process of listing the first REIT as of May 2019. The Mexican and the Brazilian REIT markets started in 2004 and 1993, respectively, but these started to grow only after regulation changes initiated in 2007 and 2008, respectively.

The evidence suggests that the group’s ‘main bank’, which provides debt financing to the firm, owns some of the group firm equity, may even place bank executives in top management positions and plays an important role especially in rescuing financially distressed group firms to reduce the cost of such financial distress (Sheard, 1989; Hoshi et al., 1990; Hoshi & Kashyap, 2001).

Section 2 provides details of the pre-war conglomerates and post-war business groups observed in Japan.

In Brazil, India, Mexico, South Korea, and Thailand, we observe business groups that are characterized by conglomerates, similar to Japanese keiretsu. In China and Singapore, we observe groups of corporations linked closely to their governments.

The history behind the emergence of keiretsu is well summarized in Yafeh (2003).

Texts in parentheses are the names of the President’s Councils (shacho-kai) of keiretsu groups, which are often used to refer to these 6 keiretsu groups.

J-REITs have a fiscal period that ends in different months. We mimic the COMPUSTAT convention and assign REITs with a fiscal period ending in March through August to the first half of the year and REITs with a fiscal period ending in September through February to the second half of the year.

FFO is equal to a REIT’s net income, excluding gains or losses from sales of property, and adding back real estate depreciation. FFO is considered as a more suitable measure of the profitability of REITs than GAAP earnings, because many investment properties increase in value over time, while GAAP earnings calculation requires that all REITs depreciate their investment properties. FFO also subtracts any gains on sales of property because they are considered to be non-recurring.

The volatility regressions were also run for rolling 10-year periods (i.e. 20 half-year periods) as a robustness check to examine if the effect is stable over time.

The regressions were run with the additional control variables for the proportions of office, residential, retail, and logistics properties, and the results are shown in the section of Robustness checks.

According to the definitions set by the Japan Meteorological Agency, in the case of SI:4, most people feel the earthquake, and most sleeping people wake up. With SI:5–, the majority of people feel fear and try to hang on to something. With SI:5+, most people feel difficulty walking. With SI:6–, it becomes difficult to stand. With SI:6+ and 7, it becomes impossible to move, and people get thrown off balance.

We choose this pre-test period to minimize the potential influence of the Global Financial Crisis.

To obtain correct standard errors with our panel data, we use a Gaussian generalized linear model (GLM) with identity link and exchangeable correlation structure (i.e. assuming that that within a cluster any two observations are equally correlated, but there is no correlation between observations from different clusters).

With the more formal regression analyses, we control important firm and property characteristics.

A t-test of the mean difference for each of these variables confirms that the differences are not statistically significant. However, we do not report the results of the t-tests, because balance is a characteristic of the observed sample and not a hypothetical population. Thus, t statistics below 2, for example, have no special relevance for assessing balance.

Short-term debts are debts with maturities equal to or shorter than 1 year and long-term debts are those with maturities longer than 1 year. Statistics shown in Panel B exclude bonds issued by REITs. Note that the average maturity of the bank loans originated during the period between the second half of 2009 and the second half of 2011 (shown in Panel B of Table 7) is exceptionally short. For the overall study period between 2004 and 2018, the average maturities of bank loans and corporate bonds used by these J-REITs are 1309.98 days (3.59 years) and 2615.87 (7.17 years), respectively, which are in line with statistics reported for the U.S. REITs.

We collected data from the loan release database provided by Japan REIT DB.

During the post-earthquake period (2011 h1 and 2011 h2), only 4 out of 15 non-keiretsu REITs were able to take out the new loans from keiretsu banks, while 10 out of 15 keiretsu REITs were able to take out the new loan from the keiretsu banks. This fact also prevents us from conducting formal regression analyses meaningfully.

We thank the anonymous referee for suggesting this additional analysis.

References

Almeida, H., & Wolfenzon, D. (2006). A theory of pyramidal ownership and family business groups. Journal of Finance, 61(6), 2637–2681.

Aoki, M. (1988). Information, incentives and bargaining in the Japanese economy. Cambridge University Press.

Aoki, M. (1994). Monitoring characteristics of the main bank system: An analytical and developmental view. In The Japanese Main Bank system. Oxford University Press.

Berglof, E., & Perotti, E. (1994). The governance structure of the Japanese financial keiretsu. Journal of Financial Economics, 36(2), 259–284.

Bertrand, M., Mehta, P., & Mullainathan, S. (2002). Ferreting out tunneling: An application to Indian business groups. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 121–148.

Byun, H., Choi, S., Hwang, L., & Kim, R. (2013). Business group affiliation, ownership structure, and the cost of debt. Journal of Corporate Finance, 23(5), 311–331.

Cannon, S. E., & Vogt, S. C. (1995). REITs and their management: An analysis of organizational structure, performance, and management compensation. Journal of Real Estate Research, 10(3), 297–317.

Capozza, D. R., & Seguin, P. J. (2000). Debt, agency, and management contracts in REITs: The external advisor puzzle. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 20(2), 91–116.

Capozza, D. R., & Seguin, P. J. (2003). Inside ownership, risk sharing and Tobin’s q-ratios: Evidence from REITs. Real Estate Economics, 31(3), 367–404.

Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E. R., Heugens, P. P., Van Essen, M., & Van Oosterhout, J. (2011). Business group affiliation, performance, context, and strategy: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 437–460.

Chen, C. R., Guo, W., & Tay, S. P. (2010). Are member firms of corporate groups less risky? Financial Management, 39(1), 59–82.

Choi, J. J., Jo, H., Kim, J., & Kim, M. S. (2018). Business groups and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(3), 931–954.

Claessens, S., Fan, J. P., & Lang, L. H. (2006). The benefits and costs of group affiliation: Evidence from East Asia. Emerging Markets Review, 7(1), 1–26.

Cochran, W. G. (1968). The effectiveness of adjustment by subclassification in removing bias in observational studies. Biometrics, 24(2), 295–313.

Downs, D. H., Ooi, J. T. L., Wong, W. C., & Ong, S. E. (2016). Related party transactions and firm value: Evidence from property markets in Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singapore. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 52(4), 408–427.

Ferris, S. P., Kim, K. A., & Kisabunnarat, P. (2003). The cost (and benefits?) of diversified business groups: The case of Korean chaebols. Journal of Banking & Finance, 27(2), 251–273.

Gaur, A. S., Kumar, V., & Singh, D. (2014). Institutions, resources, and internationalization of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, 49(1), 12–20.

Gerlach, M. L. (1992). Alliance capitalism: The social organization of Japanese business. University of California Press.

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15(3), 199–236.

Hoshi, T., & Kashyap, A. (2001). Corporate financing and governance in Japan. MIT Press.

Hoshi, T., Kashyap, A., & Scharfstein, D. (1990). The role of banks in reducing the costs of financial distress in Japan. Journal of Financial Economics, 27(1), 67–88.

Hsieh, C.-H., & Sirmans, C. F. (1991). REITs as captive-financing affiliates: Impact on financial performance. Journal of Real Estate Research, 6(2), 179–189.

Jia, N., Shi, J., & Wang, Y. (2013). Coinsurance within business groups: Evidence from related party transactions in an emerging market. Management Science, 59(10), 2295–2313.

Kensy, R. (2001). Keiretsu economy-new economy? Japan’s multinational enterprises from a postmodern perspective. Palgrave.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (1997). Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 75(4), 41–51.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (2000a). Is group membership profitable in emerging markets? An analysis of diversified Indian business groups. Journal of Finance, 55(2), 867–891.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (2000b). The future of business groups in emerging markets: Long run evidence from Chile. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 268–285.

Khanna, T., & Rivkin, J. (2000). Ties that bind business groups: Evidence from an emerging economy. Harvard Business School Working Paper.

Khanna, T., & Yafeh, Y. (2005). Business groups and risk sharing around the world. Journal of Business, 78(1), 301–340.

Kim, H., Hoskisson, R. E., & Wan, W. P. (2004). Power dependence, diversification strategy, and performance in keiretsu member firms. Strategic Management Journal, 25(7), 613–636.

Li, Q., & Chuen, D. L. K. (2018). Government ownership and firm value: Evidence from Singapore REITs. Working Paper, University of Florida.

Lincoln, J. R., & Shimotani, M. (2009). Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s business networks? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? Working paper series, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, .

Mahmood, I. P., Zhu, H., & Zaheer, A. (2017). Centralization of intergroup equity ties and performance of business group affiliates. Strategic Management Journal, 38(5), 1082–1100.

Nakatani, I. (1984). The economic role of financial corporate grouping. In M. Aoki (Ed.), The economic analysis of the Japanese firm. North-Holland.

Peng, M. W., Lee, S., & Tan, J. J. (2001). The keiretsu in Asia: Implications for multilevel theories of competitive advantage. Journal of International Management, 7(4), 253–276.

Ray, S., & Ray, C. B. (2018). Business group affiliation and corporate sustainability strategies of firms: An investigation of firms in India. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(4), 955–976.

Sheard, P. (1989). The main bank system and corporate monitoring and control in Japan. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 11(3), 399–422.

Wei, P., Hsieh, C. H., & Sirmans, C. (1995). Captive financing arrangements and information asymmetry: The case of REITs. Real Estate Economics, 23(3), 385–394.

Wong, W.-C., Ong, S.-E., & Ooi, J. T. L. (2013). Sponsor backing in Asian REIT IPOs. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 46(2), 299–320.

Yafeh, Y. (2003). Japan’s corporate groups: Some international and historical perspectives. In M. Bloomstrom, J. Corbett, F. Hayashi, & A. Kashyap (Eds.), Structural impediments to growth in Japan. University of Chicago Press.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland (HES-SO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

No. | REIT name | Sponsor name | Keiretsu | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Activia Properties Inc. | Tokyu RE | 0 | diversified |

2 | Advance Residence Investment Corporation | Itochu Corporation | 1 | residential |

3 | Advance Residence Investment Corporation (old) | Itochu Corporation | 1 | residential |

4 | AEON REIT Investment Corporation | AEON | 0 | retail |

5 | Comforia Residential REIT, Inc | Tokyu RE | 0 | residential |

6 | CRE Logistics REIT, Inc. | CRE | 0 | logistics |

7 | Daiwa House REIT Investment Corporation | Daiwa House | 0 | diversified |

8 | Daiwa House REIT Investment Corporation (old) | Daiwa House | 0 | retail |

9 | Daiwa Office Investment Corporation | Daiwa Securities | 0 | office |

10 | Frontier Real Estate Investment Corporation | Mitsui RE | 1 | retail |

11 | Fukuoka REIT Corporation | Fukuoka RE | 0 | diversified |

12 | Global One Real Estate Investment Corp. | Meiji Yasuda Life | 1 | office |

13 | GLP J-REIT | GLP | 0 | logistics |

14 | Hankyu Hanshin REIT, Inc. | Hankyuu Rail | 1 | diversified |

15 | Healthcare & Medical Investment Corporation | Mitsui Sumitomo Bank | 1 | health care |

16 | Heiwa Real Estate REIT, Inc. | Heiwa RE | 0 | diversified |

17 | Hoshino Resorts REIT, Inc. | Hosino Resort | 0 | hotel |

18 | Hulic Reit, Inc. | Hulic | 0 | diversified |

19 | Ichigo Hotel REIT Investment Corporation | Ichigo Group | 0 | hotel |

20 | Ichigo Office REIT Investment Corporation | Ichigo Group | 0 | office |

21 | Ichigo REIT (old) | Creed | 0 | office |

22 | Industrial & Infrastructure Fund Investment Corporation | Mitsubishi Corporation | 1 | logistics |

23 | Invesco Office J-REIT, Inc. | Invesco | 0 | office |

24 | Invincible Investment Corporation | Fortress | 0 | diversified |

25 | Japan Excellent, Inc. | Shinnittetsu Kowa RE | 0 | office |

26 | Japan Hotel and Resort, Inc. | Goldman Sachs | 0 | hotel |

27 | Japan Hotel REIT Investment Corporation | SC Capital | 0 | hotel |

28 | Japan Logistics Fund, Inc. | Mitsui Corporation | 1 | logistics |

29 | Japan Prime Realty Investment Corporation | Tokyo Tatemono | 1 | diversified |

30 | Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation | Mitsubishi RE | 1 | office |

31 | Japan Rental Housing Investments Inc. | Daiwa Securities | 0 | residential |

32 | Japan Retail Fund Investment Corporation | Mitsubishi Corporation | 1 | retail |

33 | Japan Senior Living Investment Corporation | Kenedix | 0 | health care |

34 | Japan Single-residence REIT Inc. | Invoice | 0 | residential |

35 | Kenedix Office Investment Corporation | Kenedix | 0 | office |

36 | Kenedix Residential Next Investment Corp. | Kenedix | 0 | residential |

37 | Kenedix Retail REIT Corporation | Kenedix | 0 | retail |

38 | LaSalle Japan REIT Inc. | LaSalle | 0 | diversified |

39 | LaSalle LOGIPORT REIT | LaSalle | 0 | logistics |

40 | LCP Investment Corporation | LCP | 0 | residential |

41 | Marimo Regional Revitalization REIT, Inc. | Marimo | 0 | diversified |

42 | MCUBS MidCity Investment Corporation | Mitsubishi Corporation | 1 | office |

43 | Mirai Corporation | Mitsui Corporation | 1 | diversified |

44 | Mitsubishi Estate Logistics REIT Investment Corporation | Mitsubishi RE | 1 | logistics |

45 | Mitsui Fudosan Logistics Park Inc. | Mitsui RE | 1 | logistics |

46 | Mori Hills REIT Investment Corporation | Mori Building | 0 | office |

47 | MORI Trust Hotel REIT, Inc | Mori Trust | 0 | hotel |

48 | MORI TRUST Sogo Reit, Incorporation | Mori Trust | 0 | diversified |

49 | New City Residence Investment Corporation | CBRE | 0 | residential |

50 | Nippon Accommodations Fund Inc. | Mitsui RE | 1 | residential |

51 | Nippon Building Fund Incorporation | Mitsui RE | 1 | office |

52 | Nippon Commercial Investment Corporation | Pacific | 0 | office |

53 | Nippon Healthcare Investment Corporation | Daiwa Securities | 0 | health care |

54 | Nippon Prologis REIT, Inc. | Prologis | 0 | logistics |

55 | NIPPON REIT Investment Corporation | Soujitsu | 1 | office |

56 | Nippon Residential Investment Corporation | Pacific | 0 | residential |

57 | Nomura Real Estate Master Fund, Inc. | Nomura RE | 0 | diversified |

58 | Nomura Real Estate Master Fund, Inc. (old) | Nomura RE | 0 | diversified |

59 | Nomura Real Estate Office Fund, Inc. | Nomura RE | 0 | office |

60 | Nomura Real Estate Residential Fund, Inc. | Nomura RE | 0 | residential |

61 | One REIT, Inc | Mizuho Trust Bank | 1 | office |

62 | Ooedo Onsen REIT Investment Corporation | Ooedo Onsen | 0 | hotel |

63 | ORIX JREIT Inc. | ORIX | 0 | diversified |

64 | Premier Investment Corporation | NTT | 0 | diversified |

65 | Prospect Reit Investment Corporation | Prospect | 0 | residential |

66 | Sakura Sogo REIT | Galileo | 0 | diversified |

67 | Samty Residential Investment Corporation | Samty-Daiwa | 0 | residential |

68 | Sekisui House Reit, Inc. | Sekisui House | 1 | diversified |

69 | Sekisui House Residential Investment Corporation | Sekisui House | 1 | residential |

70 | Star Asia Investment Corporation | Star Asia | 0 | diversified |

71 | Starts Proceed Investment Corporation | Starts Corporation | 0 | residential |

72 | Tokyu REIT, Inc. | Tokyu Rail | 0 | diversified |

73 | Top REIT, Inc. | Mitsui Sumitomo Bank | 1 | diversified |

74 | Tosei REIT Corporation | Tosei | 0 | diversified |

75 | United Urban Investment Corporation | Marubeni | 1 | diversified |

Appendix 2

Panel A: VFFOA regression with property type variables (overall period)

B | t | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Keiretsu | -0.446 | −1.74 | * |

Size | −0.446 | −1.32 | |