Abstract

We explore a new investment dimension relating hedge fund exposure to the real estate market. Using fund level data from 1994 to 2012 from a major hedge fund data vendor, we identify 1,321 hedge funds as having significant exposure to direct or securitized real estate. We test for the economic impact of real estate exposure. Our analysis shows that real estate exposure does not increase fund performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Florance et al. (2010) for a detailed estimation of the value of total U.S. commercial real estate property.

CIA The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html.

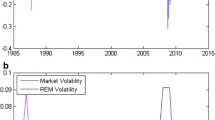

For example, beginning with Ibbotson and Siegel (1984) a lengthy literature examines the diversification benefits in the context of modern portfolio theory through the correlation between real estate investments and other asset classes. In addition, Sirmans and Sirmans (1987), Liu, et al. (1990), Chan et al. (1990), Webb et al. (1992), Grauer and Hakansson (1995), and Peterson and Hsieh (1997) among many provide evidence on the role of real estate in asset allocation and modern portfolio theory. In addition, real estate investments during the previous decade significantly outperformed broader stock market indexes. For example, over the period from 2000 to 2010, real estate investment trusts (REITs) had a compound annual total return of 10.6% compared to a -0.95% compound annual total return for the S&P500 (See The Role of Real Estate in Weathering the Storm, National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts: http://www.reit.com/DataAndResearch/ResearchResources/~/media/PDFs/Weathering-The-Storm-Special-Report-2012.ashx). Figure 1 shows the performance of an equally-weighted hedge fund index across all strategies (available from TASS), the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT) index and the CRSP value-weighted market index over the period from 1994 to 2012. The figure shows that even with the significant REIT correction in 2009, the cumulative performance of securitized real estate outperforms the general hedge fund index and the broader stock market indexes. Furthermore, comparing the returns on the generic hedge fund index with the returns on the National Council of Real Estate Fiduciaries property index (NCREIF NPI) indicates a low level of correlation.

The dataset in Chung, et al. (2012) consists of private equity funds in existence over the period from 1969 to 2009. However, they note that over 90% of their funds come from the 1990 to 2005 subperiod.

The private equity returns reported in Chung et al. (2012) are based on the fund’s ultimate performance, after the private equity fund is liquidated. In contrast, our hedge fund returns are based on quarterly filings on the performance of the investments held in the hedge fund portfolio. Thus, our hedge fund return is more closely associated with the “interim IRR” discussed in Chung et al (2012). For real estate investments, the differences between “interim IRR” and final IRR can be substantial as Chung et al (2012) note that the correlation between interim and final IRRs for real estate private equity funds is only 0.228, versus 0.618 for venture capital private equity funds.

The Appendix provides a detailed description of these strategies.

A trend following strategy captures the payoff generated when the asset price exceeds certain thresholds. Fung and Hsieh (2001) model the payoff of a trend following strategy through a look-back straddle that gives the owner a right to purchase an asset at the lowest price over the life of the option, along with a put option with a right to sell at the highest price during the life of the option. Hence, the monthly return of a trend following strategy is the payoff due to the difference between the highest and lowest price of the asset less the price of the look-back straddle. The three trend following risk factors capture movements in the bond, currency and commodity markets.

We thank William Fung and David Hsieh for making their factor data available at: http://faculty.fuqua.duke.edu/~dah7/DataLibrary/TF-FAC.xls

NAREIT index return data is obtained from REIT.com. While REIT index return data is available across sectors, we use the NAREIT All REITs index return to capture the variation across the entire securitized real estate market.

Overall, we note on Table 2 that 789 funds have exposure to the NAREIT index (744 + 45) and 577 funds have exposure to the NCREIF index (532 + 45).

We evaluate and sort based on t-statistics instead of the actual coefficient, as it normalizes the estimated coefficient and hence corrects for spurious outliers.

The number of matched funds is based on a one-to-one matching procedure. Hence, we have 1,315 matched funds with real estate exposure, and 532 matched NCREIF NPI loading and NAREIT loading funds that satisfy the matching rule. Six funds have multiple matches with non-real estate funds and thus are excluded from the analysis in this section.

Since portfolios are adjusted to reflect funds that load and do not load on the real estate market factor, the two portfolios represent hedge funds with varying levels of exposure to the real estate market. The objective is to identify investment skill in selecting real estate exposure. Hence, we do not separate out the positive and negative coefficients of the real estate market factor as this would imply that the portfolio imposes a long or short selection criteria based on past hedge funds’ exposure to real estate.

We thank the anonymous referee for an insightful comment that Long/Short funds may be biasing our results. We present a robustness test based on a sample that excludes Long/Short funds.

Since holdings of actual real estate instruments such as mortgage backed securities and collateralized debt obligations are not available, our estimation procedure quantifies the performance of hedge funds through an estimated real estate exposure based method. The Markit ABX indexes may potentially provide an alternative identification method; however, these index returns are available from 2006 onwards and the onset of the financial crisis convolutes the estimation procedure. We also change the measure of direct real estate investment to a factor constructed from the NCREIF Transaction based index (TBI) that accounts for lagged and appraisal based issues inherent in the NCREIF NPI index and note that our results are robust to this alternative measure.

References

Agarwal, V., & Naik, N. Y. (2004). Risks and portfolio decisions involving hedge funds. Review of Financial Studies, 17, 63–98.

Agarwal, V., Daniel, N. D., & Naik, N. Y. (2009). Role of managerial incentives and discretion in hedge fund performance. The Journal of Finance, 64, 2221–2256.

Aragon, G. O. (2007). Share restrictions and asset pricing: evidence from the hedge fund industry. Journal of Financial Economics, 83, 33–58.

Chan, K. C., Hendershott, P. H., & Sanders, A. B. (1990). Risk and return on real estate: evidence from equity REITs. Real Estate Economics, 18, 431–452.

Chung, J. W., Sensoy, B. A., Stern, L., & Weisbach, M. S. (2012). Pay for performance from future fund flows: the case of private equity. Review of Financial Studies, 25, 3259–3304.

Florance, A., Miller, N., Peng, R., & Spivey, J. (2010). Slicing, dicing, and scoping the size of the U.S. commercial real estate market. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 16, 101–118.

Fung, W., & Hsieh, D. (1997). Empirical characteristics of dynamic trading strategies: the case of hedge funds. Review of Financial Studies, 10, 275–302.

Fung, W., & Hsieh, D. A. (2000). Performance characteristics of hedge funds and commodity funds: natural vs. spurious biases. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 35(03), 291–307.

Fung, W., & Hsieh, D. A. (2001). The risk in hedge fund strategies: theory and evidence from trend followers. Review of Financial Studies, 14, 313–341.

Fung, W., & Hsieh, D. A. (2002). Asset-based style factors for hedge funds. Financial Analysts Journal, 58, 16–27.

Fung, W., & Hsieh, D. A. (2004). Hedge fund benchmarks: a risk-based approach. Financial Analysts Journal, 60, 65–80.

Grauer, R. R., & Hakansson, N. H. (1995). Gains from diversifying into real estate: three decades of portfolio returns based on the dynamic investment model. Real Estate Economics, 23, 117–159.

Hartzell, J. C., Mühlhofer, T., & Titman, S. D. (2010). Alternative benchmarks for evaluating mutual fund performance. Real Estate Economics, 38(1), 121–154.

Ibbotson, R. G., & Siegel, L. B. (1984). Real estate returns: a comparison with other investments. Real Estate Economics, 12, 219–242.

Kosowski, R., Timmermann, A., Wermers, R., & White, H. A. L. (2006). Can mutual fund “stars” really pick stocks? New evidence from a bootstrap analysis. The Journal of Finance, 61, 2551–2595.

Kosowski, R., Naik, N. Y., & Teo, M. (2007). Do hedge funds deliver alpha? A Bayesian and bootstrap analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 229–264.

Liu, C. H., Hartzell, D. J., Grissom, T. V., & Greig, W. (1990). The composition of the market portfolio and real estate investment performance. Real Estate Economics, 18, 49–75.

Peterson, J. D., & Hsieh, C. H. (1997). Do common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds explain returns on REITs? Real Estate Economics, 25, 321–345.

Sirmans, G. S., & Sirmans, C. F. (1987). The historical perspective of real estate returns. Journal of Portfolio Management, 13(3), 22–31.

Webb, R. B., Miles, M., & Guilkey, D. (1992). Transactions-driven commercial real estate returns: the panacea to asset allocation models? Real Estate Economics, 20, 325–357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank the Real Estate Research Institute, the Penn State Institute for Real Estate Studies, and the Smeal College of Business small research grant for supporting this research. We also thank Alexei Tchistyi, Kip Womack, Jim Shilling, James Conklin and seminar participants at the 2014 ASSA conference, 2014 FMA conference and Lehigh University for their helpful comments and suggestions, however, all errors remain the responsibility of the authors.

Appendix

Appendix

Hedge Fund Investment Strategy Descriptions:

-

Convertible Arbitrage: funds that aim to profit from the purchase of convertible securities and subsequent shorting of the corresponding stock.

-

Dedicated Short Bias: funds that take more short positions than long positions and earn returns by maintaining net short exposure in long and short equities.

-

Emerging Markets: measures funds that invest in currencies, debt instruments, equities and other instruments of countries with “emerging” or developing markets.

-

Equity Market Neutral: funds take long and short positions in stocks while reducing exposure to the systematic risk of the market.

-

Event Driven funds (Distressed, Multi-Strategy and Risk Arbitrage subsectors): invest in various asset classes and seek to profit from potential mispricing of securities related to a specific corporate or market event.

-

Fixed Income Arbitrage: funds that exploit inefficiencies and price anomalies between related fixed income securities.

-

Global Macro: funds that focus on identifying extreme price valuations and often use leverage in anticipating price movements in equity, currency, interest-rate and commodity markets.

-

Long/Short Equity: funds that invest in both long and short sides of equity markets.

-

Managed Futures: funds focus on investing in listed bond, equity, commodity futures and currency markets, globally.

-

Multi-Strategy: funds that are characterized by their ability to allocate capital based on perceived opportunities among several hedge fund strategies.

-

Hedge Fund Index: an all-encompassing investment strategy across all the asset classes and styles.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ambrose, B.W., Cao, C. & D’Lima, W. Real Estate Risk and Hedge Fund Returns. J Real Estate Finan Econ 52, 197–225 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-015-9516-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-015-9516-1