Abstract

We explore the informational properties of earnings that compensation contracting requires for performance measurement. While conditional conservatism could be desirable because it can help to alleviate agency conflicts, its downside relates to the trade-off between conservatism and other important properties, such as persistence. We infer boards’ performance measurement preferences from a novel dataset of earnings realizations used to calculate executive bonus payouts (which we label compensation earnings), which can be either GAAP or non-GAAP. On average, compensation earnings do not exhibit any conditional conservatism in the full sample. The lack of conservatism holds even in subsamples with strong corporate governance and subsamples with high ex ante agency costs, suggesting optimal contract design rather than opportunism. Finally, our analyses indicate that compensation earnings are more persistent and informative than GAAP earnings. Overall our results suggest that boards trade off conservatism for other properties in measuring performance for executive compensation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout the paper, we use “conditional conservatism” and “conservatism” interchangeably.

This view is important to accounting standard setting because, when combined with the assumption that it is cost-effective for firms to use GAAP earnings for compensation performance measurement, the demand for conservatism from compensation contracting leads to the conclusion that GAAP earnings need to be conservative (Kothari et al. 2010).

For example, in discussing the performance measurement for bonus payouts, Supervalu Inc. states in its 2011 proxy statement: “The Committee may exclude all or a portion of both the positive or negative effect of external events that are outside the control of our executives, such as natural disasters, litigation or changes in accounting or taxation standards.” Source: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/95521/000104746912006444/a2209805zdef14a.htm.

A recent study by Durney et al. (2021) makes a similar argument regarding controllability and performance measures. The authors find that segment earnings exclude items that are beyond the control of segment managers, even when these items could affect segments’ ability to generate revenues.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires firms to disclose compensation earnings under the mandatory disclosure requirement of Rule 33-8732A for all material factors underlying compensation decisions.

We use “exclusions,” “adjustments,” and “differences between GAAP earnings and compensation earnings” interchangeably to refer to GAAP earnings minus compensation earnings, including cases where the difference is zero.

Several other studies, such as by Curtis et al. (2021), Black et al. (2021), Potepa (2020), and Guest et al. (2020), also examine the use of non-GAAP performance measures in bonus contracts. However, while there is evidence that non-GAAP earnings are consistently higher than GAAP earnings, suggesting that compensation earnings are less conservative, direct evidence on the extent of conditional conservatism in compensation earnings is lacking.

Black et al. (2021) find that non-GAAP EPS is of higher quality for investors when disclosed in both the annual earnings announcement and the proxy statement. They conduct a search of non-GAAP keywords to identify a sample of firms that use non-GAAP EPS in compensation contracting. By sample construction, the analysis of Black et al. is conditional on the use of non-GAAP EPS in compensation contracting. In contrast, our sample selection is not conditional on the use of non-GAAP earnings in compensation contracts; using a large comprehensive sample containing all earnings performance measures in compensation contracts, we provide evidence on the average informational properties of all earnings performance measures (both GAAP and non-GAAP, and not limited to EPS) in compensation contracts.

Kwon et al. (2001) show theoretically that, in a limited liability setting, in which penalties that can be imposed on agents are restricted, conservative performance measures arise to efficiently motivate managers.

Consistent with his argument, Lambert observes anecdotally that, in constructing the accounting performance measure for compensation purposes, firms sometimes remove the effects of restructurings or write-downs, which could undo the result of conservatism being applied in GAAP accounting.

Relatedly, Bushman et al. (2006) and Banker et al. (2009) find a positive association between the stewardship and valuation roles of accounting. Bushman et al. propose a theoretical explanation: as managerial actions have multiperiod effects that are not fully captured in current earnings, valuation earnings coefficient is included in the incentive coefficient to motivate the manager to internalize the discounted all-in value effect of current period action. A plausible mechanism for this is for performance measurement to focus on the relatively persistent (recurring) components of earnings.

The SEC rule 33-8732A, which requires expanded disclosure on executive compensation, applies to all proxy statements filed on or after December 15, 2006. However, studies suggest that disclosure is less detailed at the initial years of compliance (Robinson et al. 2011). To minimize potential sample selection issues, we start our sample in 2008.

This requirement eliminates observations where no detailed information regarding performance measures is disclosed and observations where only nonfinancial performance measures or non-earnings financial performance measures (e.g., revenue or cash flow) are used in bonus contracts.

We exclude observations in this step either because there is no disclosure of compensation earnings, or there is disclosure but (1) the performance measure is return on invested capital, where the definition of invested capital is usually not specified and the corresponding earnings figure cannot be determined, or (2) the performance measure is based on growth from the previous year, which cannot be converted to earnings without the value of previous year’s earnings used in the calculation, or (3) the performance measure is defined as performance relative to a peer group.

Excluding these observations does not affect our inferences.

For example, for observations using EBT, EBIT, or EBITDA as compensation earnings, we add back taxes, interests, and depreciation and amortization when applicable and find that the absolute difference between the resulting numbers and GAAP earnings still amounts to 1.4% of total assets at the median.

For performance measures that are on a per share basis (earnings per share and diluted earnings per share) or in ratios (return on assets and return on equity), we convert the realized performance to a dollar amount so that they are comparable to each other and comparable to GAAP earnings.

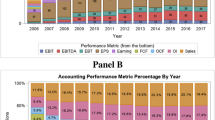

Using data collected from proxy statements of S&P 1500 firms in 2013, Curtis et al. (2021) also find that earnings per share and operating income are the most commonly used performance metrics in bonus plans.

Ederhof (2010) find 234 of these cases using a keyword search of Forms 8-K and proxy statements in Lexis/Nexis between August 23, 2004, and September 20, 2006.

Previous compensation studies (e.g., Leone et al. 2006) typically use the year-to-year change in ROA in explaining bonus payout, which effectively treats prior year’s earnings (ROA) as the performance expectation, under the assumption of a random walk in annual earnings. In untabulated analyses, we replace the independent variables with their changes from year t-1 to year t and obtain similar results.

Patatoukas and Thomas (2011) suggest that the asymmetric timeliness measure by Basu (1997) contains a bias that is attributable to scale effects. In our setting, this type of scale-induced bias likely applies both to the estimation using GAAP earnings and that using compensation earnings. Since our inference is based on the contrast of the asymmetric timeliness between GAAP earnings and compensation earnings, it is subject less to the concern raised by Patatoukas and Thomas. Ball et al. (2013) characterize the issue identified by Patatoukas and Thomas as a correlated omitted variable problem and suggest that it can be addressed using firm fixed effects. In untabulated analysis, we follow Ball et al. and control for firm fixed effects. Our inferences are unchanged.

In their composite corporate governance measure, García Lara et al. include another variable, the number of board meetings. Execucomp has stopped providing this variable in our sample period. In untabulated analyses, we include in the composite corporate governance index the value of this variable from 2005, which is the last year Execucomp reported this data item, and obtain similar results.

In untabulated analyses, we also construct an alternative aggregate governance measure by summing up the percentile ranking of governance variables and obtain the same inferences. Analyses with subsamples that are partitioned on each of the individual governance measures yield the same inferences.

We report only the coefficient estimates on RETURN × D (i.e., conservatism estimate or Basu coefficient) for brevity.

Specifically, we do not include RET and ROA as control variables because they are already used as main explanatory variables in these tests. In Table 4 compensation regressions, we do not have EXPECT_COMP and EXCESS_COMP as control variables because compensation is the dependent variable. In the Tables 5 and 6 Basu regressions, we do not include STDRET and SPREAD as control variables because they are strongly correlated with the variable of interest RETURN × D (with significant correlation coefficients at −47% and -23%, respectively), impeding interpretation of the Basu coefficient. Including these two variables frequently results in an insignificant Basu coefficient when GAAP earnings are the dependent variable.

In untabulated analyses, we scale all variables by the market value of equity and obtain similar results.

The sample size is reduced by about 23%, compared to that in Panel A of Table 5, due to the requirement of two consecutive years’ compensation earnings and GAAP earnings.

References

Abdel-Khalik, A. 1985. The effect of LIFO-switching and firm ownership on executives’ pay. Journal of Accounting Research 23: 427–447.

Adut, D., W. Cready, and T. Lopez. 2003. Restructuring charges and CEO cash compensation: A reexamination. The Accounting Review 78: 169–192.

Albuquerque, A., G. De Franco, and R. Verdi. 2013. Peer choice in CEO compensation. Journal of Financial Economics 108: 160–181.

Armstrong, C., W. Guay, and J. Weber. 2010. The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 179–234.

Baber, W., S. Kang, and K. Kumar. 1998. Accounting earnings and executive compensation: The role of earnings persistence. Journal of Accounting and Economics 25: 169–193.

Ball, R., 2001. Infrastructure requirements for an economically efficient system of public financial reporting and disclosure. Brookings Papers on Financial Services, 127–169.

Ball, R., and L. Shivakumar. 2005. Earnings quality in U.K. private firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 83–128.

Ball, R., and L. Shivakumar. 2006. The role of accruals in asymmetrically timely gains and loss recognition. Journal of Accounting Research 44: 207–242.

Ball, R., S.P. Kothari, and V. Nikolaev. 2013. On estimating conditional conservatism. The Accounting Review 88: 755–787.

Banker, R., and S. Datar. 1989. Sensitivity, precision, and linear aggregation of signals for performance evaluation. Journal of Accounting Research 27: 21–39.

Banker, R., R. Huang, and R. Natarajan. 2009. Incentive contracting and value relevance of earnings and cash flows. Journal of Accounting Research 47: 647–678.

Barclay, M., D. Gode, and S.P. Kothari. 2005. Matching delivered performance. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics 1: 1–25.

Barth, M., W. Beaver, J. Hand, and W. Landsman. 2005. Accruals, accounting-based valuation models, and the prediction of equity values. Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance 20: 311–345.

Basu, S. 1997. The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 24: 3–37.

Bettis, J., J. Bizjak, J. Coles, and S. Kalpathy. 2018. Performance-vesting provisions in executive compensation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 66: 194–221.

Bhattacharya, N., E. Black, T. Christensen, and C. Larson. 2003. Assessing the relative informativeness and performance of pro forma earnings and GAAP operating earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 36: 285–319.

Black, D., E. Black, T. Christensen, and K. Gee. 2021. Comparing non-GAAP EPS in earnings announcements and proxy statements. Management Science forthcoming.

Bradshaw, M., and R. Sloan. 2002. GAAP versus the Street: An empirical assessment of two alternative definitions of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research 40: 41–66.

Bradshaw, M., T. Christensen, K. Gee, and B. Whipple. 2018. Analysts’ GAAP earnings forecasts and their implications for accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 66: 46–66.

Bushman, R., and A. Smith. 2001. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 32: 237–333.

Bushman, R., and J. Piotroski. 2006. Financial reporting incentives for conservative accounting: The influence of legal and political institutions. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42: 107–148.

Bushman, R., Q. Chen, E. Engel, and A. Smith. 2004. Financial accounting information, organizational complexity and corporate governance systems. Journal of Accounting and Economics 37: 167–201.

Bushman, R., E. Engel, and A. Smith. 2006. An analysis of the relation between the stewardship and valuation roles of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research 44: 53–83.

Byzalov, D., and S. Basu. 2016. Conditional conservatism and disaggregated bad news indicators in accrual models. Review of Accounting Studies 21: 859–897.

Coles, J., N. Daniel, and L. Naveen. 2014. Co-opted boards. Review of Financial Studies 27: 1751–1796.

Core, J., W. Guay, and D. Larcker. 2008. The power of the pen and executive compensation. Journal of Financial Economics 88: 1–25.

Curtis, A., V. Li, and P. Patrick. 2021. The use of adjusted earnings in performance evaluation. Review of Accounting Studies forthcoming.

Dechow, P. 2006. Asymmetric sensitivity of CEO cash compensation to stock returns: A discussion. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42: 193–202.

Dechow, P., M. Huson, and R. Sloan. 1994. The effect of restructuring charges on executives’ cash compensation. The Accounting Review 69: 138–156.

Dechow, P., W. Ge, and C. Schrand. 2010a. Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 344–401.

Dechow, P., L. Myers, and C. Shakespeare. 2010b. Fair value accounting and gains from asset securitizations: A convenient earnings management tool with compensation side-benefits. Journal of Accounting and Economics 49: 2–25.

Demsetz, H., and K. Lehn. 1985. The structure of corporate ownership: Causes and consequences. Journal of Political Economy 93: 1155–1177.

De Franco, G., S.P. Kothari, and R. Verdi. 2011. The benefits of financial statement comparability. Journal of Accounting Research 49: 895–931.

Doyle, J., R. Lundholm, and M. Soliman. 2003. The predictive value of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings. Review of Accounting Studies 8: 145–174.

Durney M., K. Gee, and Z. Wiebe. 2021. Comparing internal views of performance: ASC 280 segment earnings and non-GAAP earnings. Working Paper, University of Iowa, Pennsylvania State University, and University of Arkansas.

Dyreng, S., R. Vashishtha, and J. Weber. 2017. Direct evidence on the informational properties of earnings in loan contracts. Journal of Accounting Research 55: 371–406.

Ederhof, M. 2010. Discretion in bonus plans. The Accounting Review 85: 1921–1949.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. 2010. Statement of financial accounting concepts No. 8.

Francis, J., and X. Martin. 2010. Acquisition profitability and timely loss recognition. Journal of Accounting and Economics 49: 161–178.

García Lara, J., B. García Osma, and F. Penalva. 2009. Accounting conservatism and corporate governance. Review of Accounting Studies 14: 161–201.

Gaver, J., and K. Gaver. 1998. The relation between nonrecurring accounting transactions and CEO cash compensation. The Accounting Review 73: 235–253.

Gompers, P., J. Ishii, and A. Metrick. 2003. Corporate governance and equity prices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 107–155.

Guay, W., J. Kepler, and D. Tsui. 2019. The role of executive cash bonuses in providing individual and team incentives. Journal of Financial Economics 133: 441–471.

Guest, N., S.P. Kothari, and R. Pozen. 2020. Why do large positive non-GAAP earnings adjustments predict abnormally high CEO pay? Working Paper, Cornell University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hainmueller, J. 2012. Entropy Balancing: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Analysis 20: 25–46.

Healy, P., S. Kang, and K. Palepu. 1987. The effect of accounting procedure changes on CEOs’ cash salary and bonus compensation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 9: 7–34.

Heflin, F., C. Hsu, and Q. Jin. 2015. Accounting conservatism and street earnings. Review of Accounting Studies 20: 674–709.

Holmstrom, B. 1979. Moral hazard and observability. Bell Journal of Economics 10: 74–91.

Holthausen, R., and R. Watts. 2001. The relevance of the value-relevance literature for financial accounting standard setting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 3–75.

Huang, R., C. Marquardt, and B. Zhang. 2014. Why do managers avoid EPS dilution? Evidence from debt-equity choice. Review of Accounting Studies 19: 877–912.

International Accounting Standards Board. 2010. Conceptual framework for financial reporting 2010.

International Accounting Standards Board. 2018. Conceptual framework for financial reporting 2018.

Indjejikian, R., M. Matějka, K. Merchant, and W. Van der Stede. 2014. Earnings targets and annual bonus incentives. The Accounting Review 89: 1227–1258.

Jones, J. 1991. Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research 29: 193–228.

Karuna, C. 2007. Industry product market competition and managerial incentives. Journal of Accounting and Economics 43: 275–297.

Khan, M., and R. Watts. 2009. Estimation and empirical properties of a firm-year measure of accounting conservatism. Journal of Accounting and Economics 48: 132–150.

Khanna, V., H. Kim, and Y. Lu. 2015. CEO connectedness and corporate fraud. Journal of Finance 70: 1203–1252.

Kolev, K., C. Marquardt, and S. McVay. 2008. SEC scrutiny and the evolution of non-GAAP reporting. The Accounting Review 83: 157–184.

Kothari, S., A. Leone, and C. Wasley. 2005. Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 163–197.

Kothari, S., K. Ramanna, and D. Skinner. 2010. Implications for GAAP from an analysis of positive research in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 246–286.

Kwon, Y., P. Newman, and Y. Suh. 2001. The demand for accounting conservatism for management control. Review of Accounting Studies 6: 29–51.

LaFond, R., and S. Roychowdhury. 2008. Managerial ownership and accounting conservatism. Journal of Accounting Research 46: 101–135.

LaFond, R., and R. Watts. 2008. The information role of conservatism. The Accounting Review 83: 447–478.

Lambert, R. 2010. Discussion of “implications for GAAP from an analysis of positive research in accounting.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 287–295.

Lambert, R., and D. Larcker. 1987. An analysis of the use of accounting and market measures of performance in executive compensation contracts. Journal of Accounting Research 25: 85–125.

Lawrence, A., R. Sloan, and Y. Sun. 2013. Non-discretionary conservatism: Evidence and implications. Journal of Accounting and Economics 56: 112–133.

Lawrence, A., R. Sloan, and Y. Sun. 2018. Why are losses less persistent than profits? Curtailments versus conservatism. Management Science 64: 673–694.

Leone, A., J. Wu, and J. Zimmerman. 2006. Asymmetric sensitivity of CEO cash compensation to stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42: 167–192.

Murphy, K. 1999. Executive compensation. In Handbook of labor economics, Chapter 38 Vol. 3B, ed D. Card, and O. Ashenfelter. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Murphy, K. 2013. Executive compensation: Where we are, and how we got there. In Handbook of the economics of finance, ed. G. Constantinides, M. Harris, and R. Stulz. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science North Holland.

Murphy, K., and M. Jensen. 2011. CEO bonus plans: and how to fix them. Working Paper, University of Southern California and Harvard Business School.

Nikolaev, V. 2010. Debt covenants and accounting conservatism. Journal of Accounting Research 48: 51–89.

Patatoukas, P., and J. Thomas. 2011. More evidence of bias in the differential timeliness measure of conditional conservatism. The Accounting Review 86: 1765–1793.

Potepa, J. 2020. The treatment of special items in determining CEO cash compensation. Review of Accounting Studies Forthcoming.

Robinson, J., Y. Xue, and Y. Yu. 2011. Determinants of disclosure noncompliance and the effect of the SEC review: Evidence from the 2006 mandated compensation disclosure regulations. The Accounting Review 86: 1415–1444.

Roychowdhury, S., and R. Watts. 2007. Asymmetric timeliness of earnings, market-to-book and conservatism in financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 44: 2–31.

Shalev, R., I. Zhang, and Y. Zhang. 2013. CEO compensation and fair value accounting: Evidence from purchase price allocation. Journal of Accounting Research 51: 819–854.

Sloan, R. 1993. Accounting earnings and top executive compensation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 16: 55–100.

Sloan, R. 1996. Do stock prices fully reflect information in accruals and cash flows about future earnings? The Accounting Review 71: 289–315.

Tucker, J., and P. Zarowin. 2006. Does income smoothing improve earnings informativeness? The Accounting Review 81: 251–270.

Vuong, Q. 1989. Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica 57: 307–333.

Watts, R. 2003. Conservatism in accounting part I: Explanations and implications. Accounting Horizons 17: 207–221.

Watts, R., and J. Zimmerman. 1986. Positive accounting theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Zhang, J. 2008. The contracting benefits of accounting conservatism to lender and borrowers. Journal of Accounting and Economics 45: 27–54.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the helpful suggestions from Richard Sloan (editor) and two anonymous reviewers. We thank Ying Cao, William Cready, Zhaoyang Gu, Paula Hao, Thomas Hemmer, Rong Huang, Kai Wai Hui, Mingyi Hung, Like Jiang, Bin Ke, Jing Li, Jing Liu, Linda Myers, James Ohlson, Chul Park, Grace Pownall, Haresh Sapra, Katherine Schipper, Derrald Stice, Han Stice, Nancy Su, Haifeng You, Guochang Zhang, Huai Zhang, Yinglei Zhang, Jerry Zimmerman, Luo Zuo, and seminar participants at China-Europe International Business School, Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, University of Hong Kong, University of Melbourne, and the American Accounting Association Annual Meetings for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Yang Lan, Weiping Li, Wenhao Wu, and Nashi Zeng for their excellent research assistance. Yong Zhang gratefully acknowledges the financial support from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (General Research Fund No. 15508614). A previous version of this paper was titled “Direct Evidence on Earnings Used in Executive Compensation Performance Measurement.” All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1

1.1 Examples of proxy statement disclosure of earnings used in setting compensation

1.1.1 Example 1: Masimo Corp.

(Excerpts from the proxy statement filed for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2011; italics added).

Source: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/937556/000119312512191060/d328803ddef14a.htm

For 2011, our corporate objectives focused upon achieving two financial targets: (a) total revenues of at least $446 million, and (b) GAAP earnings per share of at least $1.17. In addition, each employee, including each executive officer, had other individual objectives for the year which were designed to contribute to the achievement of our corporate objectives. In setting the objectives for the annual cash bonuses, our Compensation Committee believed that the 2011 corporate financial targets were achievable, but not easily attainable, provided that there was a maximum and sustained effort from each level of our organization. In 2011, with total revenues of $439 million, the Compensation Committee determined that we did not achieve 100% of the total revenue goal and that, with earnings per share of $1.05, we did not achieve 100% of the earnings per share goal.

1.1.2 Example 2: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

(Excerpts from the proxy statement filed for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009; italics added).

Source: http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/64040/000119312510063772/ddef14a.htm

At the beginning of 2009, the Committee established a definition of earnings per share to be used for determining the achievement of the diluted earnings per share goal for incentive compensation purposes. For the 2009 performance year, earnings per share was defined as diluted earnings per share as shown on the Consolidated Statement of Income in the Company’s Annual Report adjusted, at the discretion of the Committee, to exclude all or a portion of the positive or negative effects of the following items: (1) discontinued operations; (2) extraordinary items and any other unusual or non-recurring items, including restructurings; (3) changes in accounting principles; (4) acquisitions or divestitures; (5) changes in federal corporate tax rates; and (6) any other item of gain or loss as determined by the Committee for the year.

Under this definition, the Committee may exclude identified items from the calculation of earnings per share if such items represent non-recurring items that do not have an effect on our ongoing operations. The 2009 reported diluted earnings per share of $2.332 was adjusted by the Committee to exclude restructuring charges, the loss on the sale of Vista Research, and the gain on the sale of BusinessWeek, which resulted in an adjusted 2009 earnings per share of $2.369 for incentive compensation purposes. This level of performance achievement was 106.7% of the target goal and resulted in pool funding of 116.74% of the target incentive pool.

1.1.3 Example 3: Exelon Corp.

(Excerpts from the proxy statement filed for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012; italics added).

Source: http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1109357/000119312513107079/d474444ddef14a.htm

Note: Adjusted (non-GAAP) Operating Earnings.

Adjusted (non-GAAP) operating earnings, which generally exclude significant one-time charges or credits that are not normally associated with ongoing operations, mark-to-market adjustments from economic hedging activities and unrealized gains or losses from nuclear decommissioning trust fund investments, are provided as a supplement to results reported in accordance with GAAP. Management uses such adjusted (non-GAAP) operating earnings internally to evaluate the company’s performance and manage its operations.

Twelve months ended December 31, 2012 | Exelon |

|---|---|

2012 Adjusted (non-GAAP Operating Earnings (Loss) Per Share for Compensation Purposes | $2.91 |

Adjustment by Compensation Committee | $0.06 |

2012 Adjusted (non-GAAP) Operating Earnings (Loss) Per Share as Reported in Earnings Release | $2.85 |

Mark-to-market impact of economic hedging activities | 0.38 |

Unrealized gains related to nuclear decommissioning trust funds | 0.07 |

Plant retirements and divestitures | (0.29) |

Constellation merger and integration costs | (0.31) |

Maryland commitments related to Constellation merger | (0.28) |

Amortization of commodity contract intangibles | (0.93) |

FERC settlement | (0.21) |

Reassessment of state deferred income taxes | 0.14 |

Amortization of the fair value of certain debt | 0.01 |

Midwest Generation bankruptcy charges | (0.01) |

FY 2012 GAAP Earnings (Loss) Per Share | $1.42 |

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Na, K., Zhang, I.X. & Zhang, Y. Is conservatism demanded by performance measurement in compensation contracts? Evidence from earnings measures used in bonus formulas. Rev Account Stud 29, 809–851 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09729-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09729-6