Abstract

Tax audits are a necessary component of the tax system, but policymakers and others have expressed concerns about their potentially adverse real effects. Understanding the causal effects of tax audits has been hampered by lack of data and because typically tax audits are not randomly assigned. We use administrative data from random tax audits of small businesses to examine the real effects of being subject to a tax audit. We find that audited firms are more likely to go out of business following the audit. The effect is concentrated in firms that underreport their taxes, although we find some evidence that the administrative costs of an audit also negatively affect firm survival. Among firms that continue as going concerns, we find evidence that audits have adverse effects on future revenues but no effect on future wages, employment, or investment. Finally, we find that tax audits have side benefits, causing firms to make changes to improve their tax efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper examines the real effects on small firms of being subjected to a tax audit. Tax audits are a necessary component of the tax system. They promote compliance with the law and deter aggressive tax behavior by firms (Mills 1998; Slemrod and Yitzhaki 2002; Hanlon et al. 2007; Hoopes et al. 2012; Ayers et al. 2019a, b). However, tax audits impose costs on firms. In addition to the cash outflow from requiring noncompliant firms to pay the taxes they legally owe, all tax audits, even for tax-compliant firms, impose administrative costs by requiring the firm’s personnel to deal with the audit, comply with information requests, and otherwise defend the tax positions taken by the firm (Slemrod and Venkatesh 2002).

Policymakers have long been concerned that tax audits may have negative effects on firms. The U.S. Senate Finance Committee raised concerns about whether audits were affecting the success of small businesses as far back as 1987. Those hearings led to reforms in 1988, 1996, and 1998 to make the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) more taxpayer-friendly. Yet questions persist about the effect of tax audits on small businesses (National Taxpayers Union 2016). We are aware of no large-sample evidence that addresses this question and substantiates or refutes policymakers’ concerns.

We fill this gap in the literature by exploiting a unique dataset of small C corporations that the IRS randomly selected for audit as part of its National Research Program (NRP). Because the IRS selects firms for the NRP through stratified random sampling, using this sample allows us to avoid the selection challenges common in archival empirical research, where treatments are typically not randomly applied (Angrist and Pischke 2014).

Using this sample, we hypothesize and then test three channels through which tax audits might affect small firms. The first, we call the “direct” effect of tax audits. That is, when a firm has underpaid its tax liability, the tax audit results in an outflow of cash to the government. The second channel is the effect of “administrative costs.” This channel refers to the resources devoted to dealing with the audit itself, which takes time and effort away from running the business. We expect both the first and second channels to be costly to firms and to exert adverse effects on them. The third channel, which we call the “learning” effect, however, represents a potential benefit from being audited. Being subject to an IRS audit forces the managers of the firm to respond to information requests from the auditors, which can cause them to consider financial information that previously they may not have focused on or even collected in an organized manner. Hence, the tax audit can represent a shock that drives firms to improve their accounting and tax systems, hire new or better external advisors, or otherwise optimize their firms decision-making processes.

We begin by examining whether random tax audits affect the survival of small firms and, if so, whether the effect stems from the direct cash flow costs or the administrative costs of dealing with the audit. We focus on firm survival because it is the most consequential real effect—the one on which all other effects are conditional—and a primary concern of policymakers. We find that being subject to a tax audit increases the probability that the firm subsequently goes out of business by 1.2 to 6.0 percentage points, relative to firms that were not audited.Footnote 1

In examining the three channels through which tax audits affect firm survival, we find consistent evidence that the negative effect of tax audits is concentrated in the direct effect. Specifically, firms that underpay their tax liabilities (“noncompliant firms”) are 2.7 to 12.6 percentage points less likely to survive following the audit, depending on the measure of survival. Firms that are audited and found to have reported the correct amount of tax or that were owed a refund (“compliant firms”) experience no change in the likelihood of survival, compared to unaudited firms. We also find some evidence supporting the administrative cost channel—firms that face lengthy IRS audits are more likely to go out of business than are unaudited firms. Still, the effect is concentrated in noncompliant firms. Among firms facing lengthy audits, noncompliant firms are 1.9 to 3.0 times more likely to go out of business than are compliant firms.

We then examine less extreme but equally important potential real effects of tax audits for firms that continue to exist. We examine the effects on firm growth, including future revenues, employment, wages, and investment, as well as future tax behavior captured in effective tax rates (ETRs). In these tests, we introduce the possibility of a learning channel whereby firms may (paradoxically) benefit from being subject to a tax audit. We find that tax audits have a negative and significant impact on firms’ future revenues, leading to 21.8% lower reported revenues in the years following the audit. However, we find that being subject to a tax audit has no significant effect on firms’ employment, wages, or investment. We also find that ETRs increase and remain elevated in the years following the audit, driven by increases in formerly noncompliant firms. These results suggest that if there are benefits to firms’ operational performance via the learning channel, they are small and outweighed by the effects of the direct and administrative costs.

However, in other tests, we find some evidence of a benefit from the learning channel. Specifically, we find that being subject to a tax audit leads firms to alter their tax planning, as evidenced by an increased likelihood of converting to a flow-through entity (often a more tax-efficient organizational form for the firms in our sample (Erickson et al. 2020)). To understand how and why a firm might change its organizational form in response to a tax audit, we also test whether audited firms are more likely to change their tax preparers. We find that noncompliant firms are 2.4 percentage points more likely than compliant firms to change, although the difference is not statistically significant. These results are consistent with prior studies that suggest that firms often do not make optimal tax choices and that sophisticated tax preparers can alleviate this problem (Mahon and Zwick 2014). Our paper shows that a tax audit can be an impetus for firms to execute these changes.

Finally, we conduct supplemental analyses using nonrandom audits. The IRS regularly (and more commonly) conducts “operational” tax audits in which it selects firms based on indicators of possible noncompliance. Although operational audits are not random, they are more representative of the type of audit that a small firm would experience in the ordinary course of business. In these more generalizable tests, we largely find similar results and point estimates of the real costs and benefits of tax audits across both samples. In several cases, we find stronger statistical significance, such as in the propensity to change paid preparers.

Our paper makes at least four contributions to the literature. First, it contributes to the nascent literature on the real effects of tax enforcement on firms. Most empirical research on tax enforcement examines the effects on individual taxpayers (Slemrod 2019) or the effects of tax audits on future tax compliance (Finley 2019; DeBacker et al. 2015a, b; Li et al. 2018; Hoopes et al. 2012; Ayers et al. 2019a, b; Shevlin et al. 2017). Whether tax audits have real effects beyond future tax compliance, such as on going out of business, has, to our knowledge, never been examined in the literature. Our paper also contributes to the broader literature on the effects of government regulation on firm existence (Coglianese et al. 2014).

Second, our study answers calls for more research using randomized treatments involving actual economic agents (in this case, taxpayers) (Floyd and List 2016). As researchers often point out, endogeneity problems are endemic in the accounting literature due to the literature’s reliance on observational data (Gow et al. 2016). The toolkit of research methods that researchers can use in their attempts to uncover causal effects (e.g., instrumental variables, matching on observables, regression discontinuity) are often less than ideal in practice due to various limitations in the data (Larcker and Rusticus 2010; Tucker 2010; Lennox et al. 2012; Shipman et al. 2016). Randomized treatment represents the gold standard for identifying causal relationships (List 2011; Floyd and List 2016; Rubin 1974; Angrist and Pischke 2014). Such trials are experiments that take place in the real-life setting versus a laboratory setting and thus have the dual advantage of strong identification and generalizability (Belnap 2019). Although the IRS undertakes random NRP audits to better understand taxpayer compliance and not the effects of tax audits, our study uses NRP audits to construct a dataset that is similar to a randomized controlled trial.Footnote 2

Third, our study sheds light on an important, under-researched segment of the economy: small corporations. Structuring the tax system to allow small firms to survive and thrive is critically important for a healthy, dynamic economy (Haltiwanger et al. 2012). Moreover, small corporations are a particularly important segment of the economy from a tax authority’s perspective because they have significant opportunities for tax evasion (Hanlon et al. 2007) and are large in number. In fact, internal IRS data indicate that the total number of audit hours spent by the IRS on firms with less than $250,000 in assets is typically close to the number of audit hours spent on the largest asset class (greater than $20 billion in assets).

Finally, policymakers should find our study interesting. Tax authorities are tasked with helping taxpayers remit the legally required amount of tax, as dictated by the tax system enacted by Congress. Slemrod and Yitzhaki (1987) note that the optimal audit strategy is not the same as the revenue-maximizing strategy. Taxes shift resources from the private sector to the public sector, and tax audits contribute to this shift through the enforcement of the tax law. However, tax audits can impose additional administrative costs on firms as well as direct costs in the form of underpaid taxes that firms are required to pay, raising the possibility that tax audits cause real effects in firms that are subject to audit. Our study examines these real effects, allowing policymakers a more complete view of the costs and benefits of tax enforcement.Footnote 3

Regarding tax administration, one could argue that non-surviving firms were not viable businesses to begin with if their survival required underpaying their taxes (or, alternatively, one could argue that the tax burden is too high). Proactive outreach and education by the IRS is a key pillar of the recently enacted Taxpayer First Act (Internal Revenue Service 2021). That is, the IRS wants to make sure taxpayers have adequate information to comply with the tax law. To the extent that taxpayers do not understand their tax obligations or the advantages and disadvantages of different organizational forms when establishing a new business, greater proactive outreach is a policy solution. Furthermore, the intensity of the cash flow shock of owing additional taxes upon audit is also a policy decision, which makes it distinct from other cash flow shocks. When appropriate, the IRS could offer more leniency or flexible payment options in certain cases (e.g., when taxpayers make honest mistakes and do not harm social welfare by hurting competition).

2 Prior literature and hypothesis development

2.1 Prior literature on IRS audits

Early research on tax audits examined the factors associated with audit selection and audit outcomes (Mills 1998; Mills and Sansing 2000; Hanlon et al. 2007). More recent work seeks to understand the effects that tax authority audits have on firms. However, because audit selection and outcome data are not publicly available, most studies instead rely on variation in the probability of being selected for audit and in subsequent behavior such as tax avoidance (Hoopes et al. 2012).Footnote 4 A related strand of literature provides evidence that tax enforcement might serve as a governance mechanism by virtue of governments having a stake in firms through their tax claim on the firms’ income (Desai et al. 2007). Consistent with this link, previous studies find that firms that are more likely to experience IRS audits have a lower cost of debt (Guedhami and Pittman 2008), a lower cost of equity (El Ghoul et al. 2011), and higher financial reporting quality (Hanlon et al. 2014).Footnote 5 In our setting, these results are relevant because we use IRS data to examine the effects of an IRS audit, including the effect on the firm continuing as a going concern. If IRS audits act as a governance mechanism, these studies suggest that, at least for some firms, IRS audits may be beneficial. None of the papers mentioned above examine the effects of actually being audited, which is what we examine.

The closest studies to ours are three papers that examine the tax avoidance behavior of firms following an audit. Using IRS data, DeBacker et al. (2015a, b) find that corporations gradually increase their tax aggressiveness following an audit and then eventually reduce it. Finley (2019) uses publicly available data to examine the effects of tax audits conditional upon the type of settlement the firm receives, and finds that firms with more favorable settlements increase their tax avoidance, but firms with less favorable settlements do not change their tax planning behavior. Ayers et al. (2019a, b) use administrative tax data to examine the effect of the initiation of continual auditing on tax behavior. Finley (2019), DeBacker et al. (2015a, b), and Ayers et al. (2019a, b) focus on the effects of tax audits on future tax compliance. While these papers make important contributions, they examine a different research question than we do. We examine whether the effects of tax audits on firms extend beyond tax compliance to areas such as firms’ likelihood of survival, future growth prospects, and tax planning.

2.2 Focus on small firms

Much of the prior literature on corporate tax compliance focuses on large firms. In this paper, we focus on small firms for three reasons. First, small firms are vital for economic growth and account for a large fraction of employment and job creation (Haltiwanger et al. 2012; Lisowsky and Minnis 2020; Minnis 2011). For example, Haltiwanger et al. (2012) shows that more than 50% of employment in the U.S. is attributed to firms with 500 or fewer employees. Young firms, which tend to be small, also disproportionately contribute to both job creation and destruction due to their high growth and higher likelihood of exit. The importance of small businesses in the economy is evidenced, for example, in the recent U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Among other relief focused on small business, Congress authorized forgivable loans to small businesses in the Paycheck Protection Program, a key part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) (Congressional Budget Office 2020b; Congressional Budget Office 2020a). As of May 31, 2021, over 11 million loans totaling nearly $800 billion have been approved under the program (Small Business Administration 2021). The survival and success of small business is clearly a key objective of U.S. economic policy.

Moreover, most of the largest firms of today (e.g., Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Walmart) started off as small firms. The large, successful firm of tomorrow may well be a firm that is just starting today. Policymakers thus face a balancing act: they need to design tax systems that collect the taxes that are legally owed and necessary to fund government services, yet to structure tax systems that do not impose an undue compliance burden on taxpayers. Indeed, a tax system that imposes excessive compliance costs on small firms may be shortsighted, increasing tax revenue in the short run at the cost of less growth and tax revenue in the future.

Second, tax audits present a significant shock to small firms. In 2017, the IRS audited 18,962 corporations, but only 0.5% of corporations with assets under $250,000 (Internal Revenue Service 2017). The largest firms are audited every year, making tax audits a regular part of their business. Accordingly, these firms have staff and external advisors that are accustomed to dealing with audits. In contrast, small firms are much less likely to be audited and are therefore less equipped to deal with audits. Hence, for small firms, being subject to a tax audit can be a considerable shock.

Third, an important feature of our study is our ability to use a random assignment of a treatment to alleviate selection concerns. The IRS does not randomly audit large firms as part of its National Research Program. While alternative research designs to examine larger firms would be feasible, we are primarily interested in the effects on small firms for the reasons discussed above, and seek to use the best methods available.

2.3 Hypothesis development

We posit three channels through which tax audits could impose costs and benefits on audited firms. First, tax audits shine a bright light on firms’ tax compliance, revealing that some firms have not paid the correct amount of tax. For firms that are found to be deficient, the tax audit results in an outflow of cash to the government relative to what the firm would have had absent the audit. Second, tax audits require the firms’ managers to deal with the audit itself, taking time and effort away from running the business. We expect both the first and second channels to be costly to firms and to exert adverse effects on them, and we refer to them as direct costs and administrative costs, respectively. These effects may manifest in slower future growth, as the firm experiences lower resources and a diversion of managerial time. In the extreme, the costs may be severe enough to imperil the firms’ existence. These adverse effects are what we focus most of our attention on in this study.

The third channel, however, represents a potential benefit from being audited. Being subject to an IRS audit forces the managers of the firm to respond to information requests from the auditors, which can cause them to consider financial information they may not have previously focused on or even collected in an organized manner. Small firms often have less than ideal accounting systems and may lack experienced tax and accounting personnel. Without such systems and personnel, managers may not have the financial information they need to make effective decisions. In this sense, a tax audit can represent a shock to the firm, such that it becomes a learning experience (albeit a forced one), as managers are compelled to think about the firm’s finances in more depth than they might have otherwise. This is similar to when firms face a change in accounting standards. The new standards may provide them with new information, which may alter the firms’ decision-making (Shroff 2017). We call this channel the learning channel, and posit that it could lead managers to improve their operational performance and to reconsider (or even consider for the first time) the firm’s organization form, tax advisor, or other features of its approach to tax planning and compliance.

We examine three categories of economic outcomes in which the costs and benefits of tax audits may express themselves. The first is whether the tax audit affects firm survival. In some sense, continuing as a going concern is the most important real effect, as other real effects (e.g., effects on future revenues) are contingent on the firm continuing to operate. Because firms can cease to be a going concern in different ways, we undertake extensive analysis using a variety of measures and datasets. The second category of economic outcomes that we examine is the effects on surviving firms’ future growth and ETRs. The third category of economic outcomes is the tax planning responses of audited firms. We examine two specific tax planning responses that audited firms might take: (1) whether a firm converts to a flow-through entity, and (2) whether the firm changes its tax preparer.

3 Institutional background on IRS audits

3.1 Random audits from the National Research Program

We examine audits from the National Research Program (NRP). This is an IRS program wherein a stratified random sample of taxpayers is chosen for audit. By selecting taxpayers for audit at random, NRP audits help the IRS assess the nature and extent of noncompliance that exists in the population of taxpayers. This helps the IRS assess the characteristics of firms that are noncompliant and develop measures of the aggregate amount of tax underreporting, also known as the “tax gap,” for the population of taxpayers sampled in the NRP audit.

NRP audits are commonly conducted on individual taxpayers but are rarely conducted on corporations. However, in 2010, the IRS performed a wave of NRP audits on small corporations, randomly selecting approximately 2500 firms to be audited. The audits were performed on the firms’ corporate income tax returns (Form 1120) for the tax year 2010, with audits starting at staggered dates over a 24-month period and the first audits beginning in May 2012. With the variation in audit times, these NRP audits began concluding in December 2012 and were all completed by July 2016.Footnote 6 Audits under the NRP were conducted on corporations with less than $250,000 in assets.

The IRS divides firms into different categories, and different divisions of the IRS conduct operational audits of firms in different categories. The Small Business/Self-Employed (SB/SE) division is responsible for auditing firms with under $10 million in assets. Because audit issues (and therefore costs) may vary across divisions, having a homogeneous set of firms helps us to better identify the effects of an audit. To help illustrate the types of firms in our sample, Table 1 presents industry frequencies for the top 20 four-digit NAICS industries represented in the population from which NRP sample firms were selected.Footnote 7 These frequencies show that a large portion of the sample firms are in service industries such as medical, professional, computer, legal, management, accounting, and freight trucking. Other major industries represented are real estate and restaurants.

By virtue of their random assignment, NRP audits have the advantage of being able to eliminate the selection issue that is common in operational audit data and give estimates of the average treatment effect on a random set of firms. In addition, NRP audits have the objective of ascertaining the correctness of the whole return as opposed to a limited number of issues. Thus, the threshold for making audit adjustments can be lower in NRP audits than operational audits, leading to a potentially more precise measure of reporting compliance. In supplemental tests, we also examine operational audits. Operational audits typically occur where the return has been selected based on some indication that the taxpayer may not be compliant with the tax law. In this paper, we examine operational audits that were conducted on firms from the same population of filers from which the NRP audits were selected. This yields a sample of 4555 operational audit firms.

3.2 Data sources

We access administrative data from several sources within the IRS. First, we obtain audit information from an IRS database of closed audits. This includes aspects of the audit, such as the number of hours the IRS spent conducting it, and audit outcomes like the amount of tax deficiency from both random and operational audits. We access corporate tax returns (Form 1120) using de-identified administrative data. From these tax returns, we gather data on a number of variables for each corporation, including total assets, total receipts, and net income. To identify financial distress and other measures of firm survival, we access a database on unpaid tax assessments. Among other things, this database identifies the amount of overdue tax owed by a firm at any given time. It also identifies firms that the IRS concludes are “currently not collectible” based on their nonpayment status and response (or lack thereof) to repeated IRS inquiries. Within this set of firms, the IRS identifies firms that are “defunct” or that the IRS was unable to contact. Finally, we access information reports provided to the IRS, specifically the W-2 and Forms 1099, to obtain information on total wages paid, the number of employees at the firm, and payments received from third parties.

4 Research design and descriptive statistics

4.1 Research design

We first examine the real effects of tax audits using the NRP sample of random audits. Our research design follows Lawrence et al. (2018), where treatment firms are randomly selected from a population and then closely-matched firms are selected as control firms. The IRS selected firms for NRP audits in tax year 2010 randomly across five strata based on total receipts, with firms divided into two groups based on the month of tax year-end and sampled at different rates.Footnote 8 Thus, there are ten distinct strata, each with its own sampling rate. To form a control group, we use propensity score matching (PSM) to select the closest match for each audited firm, with each control firm matched on industry (three-digit NAICS) and coming from the same strata from which the audited firms were randomly selected.Footnote 9

Our matching approach helps improve identification in ex post cross-sectional tests where we distinguish whether the main effects are driven by noncompliance or the administrative burden of an audit. In other words, because treatment selection is random, we can draw causal inferences for the effects of random audit selection on the likelihood of going out of business. However, the nature and outcome of the audit itself are not random, which makes ex post cross-sectional comparisons based on audit characteristics potentially affected by correlated omitted variables. For example, financial distress could drive both firm survival rates and noncompliance if firms begin to underpay their corporate income tax liability as they become distressed. Indeed, there is mounting evidence that firms with financial constraints engage in more tax avoidance (Edwards et al. 2013; Law and Mills 2014). Thus, the finding that audited noncompliant firms are less likely to survive may be more a function of financial distress than a product of tax enforcement.

Our matching procedure attempts to mitigate these concerns. Specifically, we exploit the fact that the IRS has robust measures of ex ante audit outcomes and financial distress for both audited and unaudited firms. To measure ex ante audit outcomes, we use the discriminant function (DIF) score, which is a proprietary score that the IRS assigns to each filed return to identify the potential for an audit to reveal a change to the tax liability, based on the IRS’s past experience with similar tax returns.Footnote 10

To measure ex ante financial distress, we access data from the IRS database of unpaid tax assessments to identify the amount of overdue tax that is owed by our sample firms at the time of audit selection. Specifically, we calculate financial distress as the maximum balance owed in the two years prior to audit selection in tax year 2010. The amount of overdue tax is highly correlated with firm survival, and we believe it is a more direct measure of financial distress than other measures commonly used in the literature (e.g., Beaver et al. 2011). Furthermore, balance sheet information is not available for many of our sample firms, making other measures infeasible in our setting. Importantly, this variable is also available for both audited and unaudited firms. Hence, we have measures of expected audit adjustment and financial distress, even for control firms, which we use to obtain high-quality matches for the audited (i.e., treatment) firms.

In addition to the DIF score and financial distress, we match on firm size, income, and wages paid. We use total receipts to capture firm size. Taxable income is measured by the firm’s taxable income before the deduction for net operating losses (NOLs) per its corporate income tax return. Wages paid is the sum of wages paid to all employees and reported on Form W-2. We impose a caliper distance of 0.03. These procedures yield a sample of 2508 audited firms and 2508 control firms.

4.2 Measuring survival

Part of our analysis examines whether being subject to audit increases the likelihood of firm survival. We measure survival using two measures. The first measure, Out of Business, is an indicator variable equal to one if the firm stops filing income tax returns by the end of our sample period (2016), and zero if it continues filing. We use this measure because corporations are required to file tax returns for each year that they are in existence, regardless of whether they have taxable income.Footnote 11 In computing Out of Business, we make adjustments that take into account other reasons, unrelated to survival, that firms may stop filing tax returns. For example, firm owners may choose to change the business’s organizational form or continue to operate the business as a new entity as an attempt to evade taxes. Specifically, we make two adjustments. First, if a firm converts to an S corporation, we code Out of Business as zero. We are able to identify these firms because they maintain the same firm identifier (employer identification number (EIN)) after the conversion. Second, if the owner of a firm opens a new business that continues to file an income tax return at the end of our sample period, we code Out of Business as zero. To make this adjustment, we utilize IRS data on EIN applications and identify the applicant for each sample firm, then track that applicant’s new EIN applications that take place after the start of the audit.Footnote 12 Still, we acknowledge that ceasing to file an income tax return is not a perfect measure of firm survival. Hence, we utilize a second measure and perform the robustness tests described in Section 6.1.

Our second measure of survival is Defunct, which we obtain from the unpaid tax assessment database that tracks tax payments. When a firm has unpaid taxes, the IRS first sends a series of notices by mail informing the firm of its late payment status and urges it to make the required payments. If unpaid taxes are not resolved during the notice stage, the firm enters a delinquent status and may be assigned either to a call center or to a revenue officer, who in many cases attempts to make an in-person visit.Footnote 13 Based on this contact (or attempted contact), the IRS assesses the likelihood that it can recover tax payments from the firm, and may determine that the unpaid taxes are uncollectible. In addition, the IRS identifies a reason why such taxes are uncollectible, including that the firm is “defunct.” Our variable Defunct is an indicator variable equal to one for any firm that enters this IRS designation in the database following the audit, and zero otherwise. Note that our Defunct variable is likely an underestimate of the true magnitude of business failure because only firms that have delinquent tax payments appear in this database. In other words, firms that go out of business without first having a delinquent tax payment are not captured and are assumed to still be in business.

4.3 Descriptive statistics for the NRP sample of random tax audits

Table 2 contains descriptive statistics for the firms audited as part of the NRP (Panel A), tests of means between the audited firms and control firms (Panel B), and a correlation table for the audited firms (Panel C).Footnote 14 As expected, Panel A reveals that the audited firms are small at the time they are selected for audit. The mean firm subject to an NRP audit has $1.2 million in revenue and around $60,000 in assets. On average, the firms have 12 employees, with total wages of around $400,000. The mean firm has a reported taxable income of $209 (before any audit adjustments), with the median firm reporting zero taxable income.

Panel A reveals that the audits are potentially important to the firms, especially considering the firms’ small size. The average audit lasts 417 days, involves 67 hours of IRS employee time, and results in an average audit adjustment of around $6700. There are firms with negative audit adjustments (refunds) in our sample, but the instances are rare (less than 5% of audited firms) and the amounts are small. Panel B compares the means and medians of the firm-level variables for the audited firms to those of the control sample using t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, respectively. Our control sample closely mirrors the audited firms, with none of the means or medians being significantly different between the samples. Panel C presents the correlations among the variables for the audited firms. The audit adjustment is increasing in the intensity of the audit, as reflected in the number of days and the hours spent on the audit. Audit adjustments are also increasing in firm size, net income, number of employees, total wages, and distress.

5 Results

5.1 Do tax audits increase the likelihood of business failure?

After creating the dataset of audited and control firms, we examine whether tax audits increase the likelihood of a business failing to survive. We present our results in both figure and tabular form. In Fig. 1, we examine the number of firms that are Out of Business between 2010 (the year that is audited) and 2016 (the end of our sample period). Note that we calculate Out of Business following the approach described in Section 4.2, except that for graphical purposes we compute it on an annual basis rather than based on firms’ filing status as of 2016 (as we do in the regressions). Because control firms were not audited, we track Out of Business and compliance status for each control firm relative to the event time and compliance status of its matched audited firm. Panel A shows that there is an upward trend for both groups, as some firms will cease to exist over time for any number of reasons unrelated to being audited. But the figure illustrates a clear divergence between audited firms and control firms. By 2016, 913 audited firms have gone out of business, compared to 763 control firms.

Number of Firms That Go Out of Business over Sample Period. This figure portrays the rate at which random audit (NRP) and control firms go out of business over our sample period of 2010 to 2016. For this figure, we compute the number of firms that are Out of Business following the approach for this variable detailed in Appendix 1, but on a year-by-year basis. Note that the variable Out of Business used in regressions is computed as of the end of our sample period (2016). Panel A. includes the full sample; Panel B. includes only noncompliant firms; and Panel C. includes only compliant firms. We assign control firms to the event time of their matched NRP audit firm. All variables are defined in Appendix 1

We then split the sample into two groups depending on the results of the audit. The IRS audit can either reveal firms to be tax compliant or noncompliant (firms with positive audit adjustments). The results in Panels B and C indicate a striking difference in the rate of firm survival following an audit. The firms that the IRS finds to be compliant continue to survive after the audit at close to the same rate as the control firms. However, the firms that the IRS finds to be noncompliant have a noticeably higher likelihood of going out of business.

Next, we formally test whether being audited by the IRS affects business failure. Our main specification is the following linear probability model with one observation per firm (no time series)Footnote 15:

where Yi is either Out of Business or Defunct. Audited is an indicator variable equal to one for firms that are audited by the IRS (NRP firms) and zero for control firms, which are not audited. We weight each observation using the sampling weights (inverse probability of being selected) to generalize the results to the population.

We present the results in Table 3. In all tables using NRP audits, we exclude control variables because the treatment is randomly assigned, and, thus, in expectation, all covariates are equal (Angrist and Pischke 2014).Footnote 16 Columns 1–3 use the dependent variable Out of Business; columns 4–6 use the dependent variable Defunct. In columns 1 and 4, we estimate Eq. (1) on the full sample of audited firms and control firms. The results indicate that, on average, audited firms are 6.0 percentage points more likely to be Out of Business and 1.2 percentage points more likely to be Defunct following the audit than are control firms.

We next partition the audited sample into those that the IRS finds to be tax compliant and those that the IRS finds to be tax noncompliant. In columns 2 and 5, we estimate Eq. (1) on the noncompliant firms and their unaudited control firms. We find that Audited has a large, positive, and statistically significant effect on business failure. Specifically, audited firms that are found to be noncompliant are 12.6 percentage points more likely to be Out of Business and 2.7 percentage points more likely to be Defunct following the audit, compared to control firms. In columns 3 and 6, we examine firms that the IRS audits and finds to be compliant and their unaudited control firms. The results show coefficients on Audited that are insignificantly different from zero, indicating that for firms that the IRS finds to be tax compliant, being audited has no effect on the likelihood of going out of business after the audit. Cross-equation tests indicate that the difference in Audited coefficients between columns 2 and 3 and columns 5 and 6 are statistically significant.

Overall, the finding of a significant positive effect of an IRS audit on the likelihood of business failure among noncompliant firms but no significant effect for tax compliant firms suggests that the enforcement of correct tax liability (the direct cost channel) affects the likelihood that noncompliant firms will survive. However, these results also suggest that, for compliant firms, the administrative costs of dealing with the audit do not significantly affect the firms’ likelihood of surviving. In our next analysis, we examine the effects of these administrative costs on firm survival in more detail.

5.2 Effects of administrative costs of tax audits on survival

In Table 4, we examine variation in the administrative costs of the audit using two proxies: the IRS auditor hours spent on the audit and the length of the audit in days. Our assumption is that the administrative cost to the firm is increasing in the number of hours spent by the IRS auditor on the audit and the length of the audit. This assumption is likely imperfect, particularly for audit length, as the firm has some discretion in how long an audit takes by responding quickly or slowly to information requests. In columns 1–2 and 5–6 we partition the sample into low and high administrative cost based on median audit hours. We show that the increased probability of Out of Business for audited firms is significant for both low and high hour audits (columns 1 and 2), and the effects are insignificantly different from one another. The increased probability of Defunct is found only in the high audit hours partition (column 6), but the result is not significantly different from in the low audit hours partition (column 5). Overall, this suggests that the administrative cost of complying with an IRS audit, as measured by audit hours, is not a significant factor in whether the firm survives.

Next, we partition the sample into low and high administrative costs based median audit length in days. The results, in columns 3–4 and 7–8, reveal that the effect of the audit on firm survival is significant in audits that are above the median length but not in audits that are below median length. One shortcoming of the tests in Table 4 is that they partition the sample only on audit length and hours, which may conflate the costs of being found to be noncompliant (i.e., having to pay the correct amount of tax) with the administrative cost of the audit. Accordingly, we next partition on both the administrative costs of the audit and whether the IRS audit reveals the firm to be tax compliant.

In Table 5 we partition the sample four ways based on compliance and level of administrative cost. We examine the following partitions separately: (1) tax noncompliant, low administrative cost; (2) tax noncompliant, high administrative cost; (3) tax compliant, low administrative cost; and (4) tax compliant, high administrative cost. We create the partitions based on compliance status and at the median of our administrative cost variable (either audit hours or audit length) using the full sample.Footnote 17 Partitioning at the full sample level is important as it permits the full variation of the partitioning variables to determine each cell’s composition. This approach also results in partitions with unequal observations.

In Panel A, we examine Out of Business as the dependent variable. Columns 1–4 use IRS auditor hours as a proxy for administrative cost, while columns 5–8 use audit length. The results in columns 1–4 show that the positive relation between being audited and the firm going out of business holds only in subsamples of noncompliant firms. Moreover, cross-equation tests show no significant difference in the coefficients on Audited between high and low administrative costs for noncompliant or compliant firms (i.e., columns (1) vs. (2) and columns (3) vs. (4)).

However, in columns 5–8 (which use audit length as the proxy for administrative costs), we find that the results are concentrated in longer audits. Cross-equation tests show statistically significant differences between low-length and high-length audits among noncompliant (columns (5) vs. (6)) but not compliant firms (columns (7) vs. (8)). We also find much larger negative effects among noncompliant firms, compared to compliant firms. For example, among high-length audits, noncompliant audited firms are 3.0 times more likely to be Out of business than compliant audited firms (18.7 percentage points compared to 6.2 percentage points), and the difference is statistically significant (e.g., columns (6) vs. (8)).

We repeat this analysis using Defunct as the dependent variable and find similar results in terms of sign and significance in Panel B. We again find some evidence that longer audits are significantly related to business failure and that the largest effects are found in noncompliant firms, which are 1.9 times more likely to be Defunct than compliant firms (3.1 percentage points compared to 1.6 percentage points).

Overall, we find that longer audits are associated with decreased survival rates, consistent with the administrative cost channel. A caveat is that audit length is in part determined by the firms’ timeliness in responding to information requests and is therefore an imperfect measure of administrative burden. We continue to find that the magnitude of the negative relation between IRS audits and firm survival is largest among noncompliant firms and that across nearly all specifications, noncompliant firms have significantly lower survival rates than compliant firms with similar administrative costs. Ultimately, our results suggest that longer audits result in significant administrative costs but that the negative effect of random IRS audits on firm survival is concentrated in noncompliant firms, consistent with the importance of the direct cost channel.

5.3 Do tax audits affect future revenues, wages, employment, and investment?

In this section, we examine the effect of IRS audits on future revenues, wages, employment, and investment, using the following difference-in-differences specification:

where Y is one of our four outcome variables: the natural log of total wages paid, the natural log of the number of employees, the natural log of investment, and the natural log of total receipts. Our sample period extends from t-5 to t + 5, relative to the year that the audit begins. We calculate investment using the total current year depreciation expense (from Form 4562), as most investments for the firms in our sample are fully depreciable for tax purposes in the first year. Audited is an indicator variable equal to one for firms that are randomly audited and zero for our PSM sample of control firms. Post is an indicator variable equal to one for tax years after the start of the audit, and zero otherwise. β3 is the difference-in-differences estimator. We also include firm and year fixed effects in the regression.

We present the results of estimating Eq. (2) in Table 6. As in Table 3, we examine each of the dependent variables in three specifications: one that includes the full sample, one that includes only noncompliant firms, and one that includes only compliant firms. Note that Audited is omitted because it is subsumed by the firm fixed effects. Post is not subsumed because the individual audits begin and end at different dates over several years after 2010 (when firms were selected for audit).

Our results show no significant effects of random tax audits on the wages, employment, or investment of audited firms. However, we do find that random tax audits adversely affect future firm revenue and that the effects are experienced by both noncompliant and compliant firms. Moreover, the coefficients suggest that the magnitude of the effect is economically significant, with a 24% reduction in revenue for noncompliant firms and a 21% reduction for compliant firms.

This effect on firm performance is intuitive, given our main result that tax audits can affect firm survival, and may stem from administrative costs, as both compliant and noncompliant firms experience a negative effect. The results are also consistent with previous studies that document a “bomb-crater” effect of tax audits (DeBacker et al. 2015a, b; Guala and Mittone 2005; Mittone 2006), where firms misbehave immediately after an audit because they believe they are unlikely to be audited again. In particular, the fact that less manipulable measures such as employment and wages see no effect, whereas revenue, which can be easily underreported, declines, points to the bomb-crater effect. However, these results do not support a significant positive effect on operational performance from the learning channel. If there is a positive effect from learning on these outcomes, it is small and outweighed by the negative effect from direct and administrative channels.

5.4 Effective tax rates following IRS audits

To provide further insight on the effects of tax audits, we next examine subsequent effective tax rates (ETRs) similar to DeBacker et al. (2015a, b). We follow the approach in that paper and Plesko (2003) to create an ETR measure that requires only taxes and income reported on the return (see Appendix 1 for more details on variable construction). As in DeBacker et al. (2015a, b), this computation results in a measure that is much lower than typical cash and GAAP ETRs using financial statement data but is informative of firms’ tax behavior.

DeBacker et al. (2015a, b) document a U-shaped pattern of ETRs following audits, which is consistent with two effects. The first is type-updating, where Bayesian taxpayers revise their probabilities of being high risk upward if they experience audits. Firms immediately decrease tax aggressiveness after an audit but gradually increase it over the years they are not audited. The second is a bomb-crater effect, where taxpayers believe they are unlikely to be audited again immediately following an audit. These firms initially increase tax aggressiveness but decrease it over time as their perceived audit probability increases.

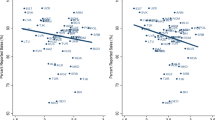

In Fig. 2, we illustrate the pattern of ETR over time relative to the year the audit begins (t = 0), using a sample of t = −5 to t = 5. In Panel A, we present the results of the full sample; in Panels B and C, we present the results of samples of noncompliant and compliant firms, respectively. Like DeBacker et al. (2015a, b), our results are consistent with both type-updating and the bomb-crater effect occurring. We show that ETR increases immediately following the audit but then follows a U-shaped pattern over the next three years. Further, we show that this effect is driven primarily by noncompliant firms. However, in contrast to the findings in DeBacker et al. (2015a, b), in our setting the type-updating effect largely dominates, with audited firms in the post period overall reporting higher ETRs than before the audit. Because we examine only small firms (for which the ex ante audit probability is very low), being audited can dramatically raise the firm’s perceived riskiness, leading to type-updates that outweigh the bomb-crater belief that the firm will not be audited again.

ETRs Relative to Audit Start Date. This figure illustrates our analysis of ETRs over time. Our sample period extends from t-5 to t + 5, relative to the year that the audit begins. Panel A. includes the full sample; Panel B. includes only noncompliant firms; and Panel C. includes only compliant firms. We assign control firms to the event time of their matched NRP audit firm. ETR is computed following the approach in DeBacker et al. (2015a, b). All variables are defined in Appendix 1

5.5 Do tax audits affect firms’ future tax planning?

If there are learning benefits from tax audits, they are perhaps most likely to be observed in firms’ future tax planning decisions. In this sense, the tax audit can represent a shock to the firm, such that it becomes an impetus for the firm to learn and reconsider its previous tax planning (or lack thereof). We examine two tax planning outcomes that represent benefits to the firm as a result of learning: (1) whether a firm converts to a flow-through entity, and (2) whether the firm changes its tax preparer.

5.5.1 Conversion to flow-through entity

C corporations face two levels of taxation: one at the entity level, and one at the shareholder level. Thus, the earnings of a C corporation are taxed twice: first by the corporate income tax, and second by shareholder-level taxes when those earnings are distributed to shareholders as dividends. A flow-through entity, such as an S corporation, limited liability company (LLC), or partnership, on the other hand, avoids double taxation because it pays no income tax at the corporate level, and all income items flow directly to shareholders. Because the choice of organizational form involves a number of tax and nontax factors, we cannot say for certain that it is optimal for any specific firm to operate as a flow-through entity. However, small firms during the tax regime of our sample period are often more tax efficient as flow-through entities, and indeed many firms elected to be taxed as S corporations rather than as C corporations during our sample period.Footnote 18

Accordingly, in Table 7 we use two dependent variables to examine the likelihood of (1) converting to an S corporation (Convert to S Corp), or (2) converting to another flow-through entity following the audit (Apply for Flow-through EIN). An advantage of examining S corporation conversions is that firms that convert from C to S maintain the same employer identification number (EIN). Thus, tracking the firm over time is straightforward and generally without error. Convert to S Corp is an indicator variable equal to one if the firm files at least one Form 1120-S following a random audit, and zero otherwise. To track other organizational form changes, we utilize the EIN application data described above. Apply for Flow-through EIN is an indicator variable equal to one for firms whose owners apply for a new EIN that is either a partnership or an LLC, and zero otherwise.

In Table 7, we find that being audited and found to be noncompliant results in significant increases both in S corporation conversions and in applications for flow-through EINs. Column 2 shows that noncompliant firms are 4.3 percentage points more likely to convert to S corporations, which represents a 68% increase relative to control firms’ 6.3% likelihood of converting. Similarly, the results in column 5 reveal that noncompliant firms are 2.0 percentage points more likely than control firms to apply for flow-through EINs, although the coefficient is not statistically significant. We also find that the differences in Audited coefficients between compliant and noncompliant firms are both statistically significant.

Overall, the results in Table 7 provide evidence of a benefit from audits via the learning channel. These findings are striking because they shed light on a possible benefit, to the taxpayer, of being subject to a tax audit. During the period of our study, small firms, like the ones in our sample, would often benefit from the flow-through tax structure. Thus, the audit process appears to help some firms choose a more tax-efficient organizational form. It is unclear whether the audit process itself helps inform the taxpayer or whether the taxpayer learns through another means, such as by hiring external advisors to assist with the audit process. To further examine how or why a firm might convert to a flow-through entity, we next examine whether audited firms are more likely to change the paid preparer of their corporate income tax returns.

5.5.2 Changes in tax preparers

An IRS audit may compel a firm to more carefully consider its financial position and tax planning, but many firms lack the resources to have dedicated accounting personnel in house. Instead, these firms largely rely on external accounting and tax service providers. One way to observe whether firms learn from audits and begin to change their approach to tax matters is to explore whether audited firms are more likely to change the paid preparer of their corporate income tax returns. A change in the paid preparer may also reflect the mechanism through which firms convert to flow-through entities. That is, an audited firm, particularly one found to have underpaid its tax liability, likely has greater incentives to seek a new paid preparer who can help identify areas for improved tax efficiency. Hence, we next examine whether audited firms are more likely to change their paid preparers following an audit and, if so, whether this relation is concentrated among noncompliant firms.

We explore this relation in Table 8 with a specification that follows Eq. (1) but uses a new dependent variable, Change Preparer. Change Preparer is an indicator variable equal to one if the firm changes its paid preparer at any time after the start of a random IRS audit, and zero otherwise. Columns 1–3 illustrate the relation between Audited and Change Preparer in the full sample of firms, the noncompliant firms, and the compliant firms, respectively. We do not find evidence that audited firms in any of the specifications are more likely to change their paid preparers.

6 Supplemental tests using operational tax audits

In this section, we conduct supplemental tests using operational tax audits. While our main tests allow for strong identification by using random tax audits, these audits are not as common as operational tax audits. There are two main differences between random and operational tax audits. First, firms are selected for operational audits based on indications of tax underreporting. Second, because of the selection differences, random audits and operational audits differ in terms of scope. Operational audits entail a more targeted and concise review based on the indicators of underreporting, whereas NRP audits involve a more comprehensive review of the tax return. Ultimately, by examining operational audits, we derive more generalizable estimates of the effects of tax audits, though at the cost of clean identification from the random application of the treatment.

For comparability with the main analysis using random audits, we gather data on all operational audits conducted in the same population from which firms that were subject to random audits were selected. To obtain a control group of unaudited firms, we perform a PSM following the same approach used for our random audit sample above. We again match on DIF score, financial distress, receipts, net income, and wages paid. This approach yields a sample of 4555 audited firms and 4555 control firms. Descriptive statistics for this sample are in Appendix 2. These descriptives show that operational audit firms are larger than firms selected for random audit (~40% greater receipts; ~80% greater assets) and that our matching procedure was effective in producing similar control firms. We repeat the tests from Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, again in the operational audit sample, and find similar results. For brevity, we tabulate only the most salient tests. As with the random audits, we formally test the effect of operational audits, with our main specification as the following linear probability model:

where Dependent Variable is either Out of Business, Defunct, Convert to S-Corp, Apply for Flow-through EIN, or Change Preparer, defined as they were for the random audit tests. Audited is an indicator variable equal to one for operational audit firms and zero for control firms. We include the same control variables used above: Size, Net Income, Wages, DIF, and Distress.

Although operational audits are not random, we believe our design has strong identification due to the unique variables we can exploit using IRS data. Furthermore, as with the random audit sample, the ability to match on ex ante financial distress helps rule out a number of alternative explanations related to firm survival. Moreover, the DIF score is a significant factor in audit selection. Thus, finding firms that have identical DIF scores suggests that the firms have similar audit probabilities and similar expected audit outcomes. However, conditional on a given DIF, whether a firm is actually audited or not is largely a function of IRS resource constraints and is therefore exogenous to the firm. Our sample therefore consists of audited (treatment) firms and unaudited (control) firms that are similar in financial distress, expected audit outcomes, and the probability of audit, in addition to firm size, net income, and wages paid.

We present the results in Table 9. In Panel A, we examine business failure, with the dependent variable Out of Business in columns 1–3 and Defunct in columns 4–6. Similar to the corresponding test on firms randomly selected for audit, we find that within noncompliant firms, operational audits have a large, positive, and statistically significant effect on the firm’s likelihood of business failure. Specifically, tax noncompliant firms receiving operational audits are 5.3 percentage points more likely to be out of business and 6.3 percentage points more likely to be defunct. We again find no significant relation in tax compliant firms. In untabulated tests, we find that this relation is driven primarily by noncompliance, not by the level of administrative costs related to the audit.

In Panel B, we examine audit benefits, with the dependent variable Convert to S-Corp in columns 1–3, Apply for Flow-through EIN in columns 4–6, and Change Preparer in columns 7–9. We find that firms that are subject to operational audits and are tax noncompliant are 6.2 percentage points more likely to convert to S corporations following the audit. However, we find no significant effect among firms that are subject to operational audits and are tax compliant, which is consistent with our results for firms that are subject to random audits. We also find that noncompliant (compliant) firms are 3.1 (2.4) percentage points more likely than control firms to apply for new flow-through EINs. Noncompliant firms are also 3.0 percentage points more likely to change their tax preparer following the audit, but there is no significant relation between being subject to an operational audit and the likelihood of changing paid preparers among firms that are found to be tax compliant.

Overall the results between the random and operational tax audit samples paint a consistent picture regarding the costs of the audit. We view the results using the operational audit sample as adding generalizability to the results using the random audit sample, despite the less tightly identified setting.

7 Robustness tests

In this section, we discuss a number of untabulated tests to examine the robustness of our main results.

7.1 Do firms go underground following tax audits?

First, we examine whether one of our dependent variables, Out of Business, is systematically overestimated by firms going underground. Specifically, we consider whether firms may have stopped filing tax returns after the tax audit even though they are still in business. We exploit the fact that when firms stop filing a tax return following an audit, in many cases there is still evidence of their existence because of third-party reporting, such as, for example, when firms accept credit card payments. Specifically, we examine whether firms in our sample that are audited and stop filing tax returns are more likely to continue to receive Forms 1099 (indicating that they continue to receive income), compared to non-audited firms that stop filing tax returns. For example, firms that accept credit cards and other electronic payments are subject to 1099-K reporting, meaning the credit card firms that process payments (Visa, MasterCard, etc.) notify the IRS of the credit card sales the firms make (Slemrod et al. 2016).

We run our standard specification using seven different dependent variables that indicate whether a firm received a Form 1099 for (1) credit card sales (1099-K), (2) interest income (1099-INT), (3) gross proceeds (1099-B), (4) dividends (1099-DIV), (5) rents, (6) royalties, or (7) non-employee compensation. Overall, we do not find strong evidence that tax audits affect firms’ receiving Forms 1099 after their last corporate income tax filings, suggesting that firms do not systematically go underground following an IRS audit.

7.2 Are the main results driven by financial distress?

One concern is that our primary findings may simply reflect financial distress. That is, distress may be a correlated omitted variable that drives both positive adjustments upon IRS audit and business failure. Although we match to control firms on ex ante financial distress, to the extent our matching procedure does not produce treatment and control groups that are similarly financially distressed, this could be a significant concern.

To alleviate this concern, we employ another matching technique, entropy balancing, for the main analyses. In Tables 3, 4 and 5, we find consistent results that the effects on business failure are concentrated in tax noncompliant firms and, to a lesser extent, firms facing long IRS audits. We tabulate our PSM results because the sample of NRP firms was selected randomly using stratified random sampling, which requires that we apply sampling weights to the regressions to provide population-level estimates of the effects of IRS audits. Entropy balancing also uses regression weights to create a control group that is balanced on the covariates identified by the user, but both the sampling weights and the entropy-balancing weights cannot be simultaneously applied.

Furthermore, we examine univariate results on the outcomes of both the financially distressed and non-distressed firms. If distress is driving the results, we would expect a large positive difference in Out of Business between the distressed and non-distressed tax noncompliant treatment firms. Similarly, we would expect large positive differences between distressed and non-distressed tax noncompliant control firms (control firms matched to noncompliant treatment firms). Instead we find that distressed firms are actually 0.4 to 4.6 percentage points less likely to be Out of Business than non-distressed firms. Furthermore, when we compare similarly distressed firms that vary only on whether they were audited, we find that audited firms are 6.4 to 10.7 percentage points more likely to be out of business. This evidence further suggests that our results are driven by the impacts of the audits, not by financial distress.

8 Conclusion

We examine the real effects of tax audits on small firms. We employ data from the IRS’s National Research Program, in which firms are randomly selected for audit. We find that audited firms are less likely to survive following the audit, but the effect is concentrated in firms that underreport their taxes. We also find some evidence that the administrative costs of an audit cause firms to cease as going concerns. We examine whether being subject to a tax audit affects the firm’s future tax avoidance and growth. In addition to the direct and administrative costs of tax audits, we consider the possibility of positive effects from forcing firms to learn about themselves. We find evidence of a statistically negative effect of tax audits on firms’ future revenues, but no significant effect on wages, employment, or investment. We also find an increase in ETRs following the audit, driven by previously noncompliant firms. While these results do not support a positive learning effect on firms’ performance, we do find evidence of a learning effect whereby audited firms convert to flow-through organizational forms at higher rates than unaudited firms.

Our study contributes to the emerging literature on the effects of tax enforcement on firm behavior. To our knowledge, there are few studies that examine corporate taxpayer behavior after a tax audit, and most focus on taxpayer compliance following an audit (DeBacker et al. 2015a, b; Finley 2019; Li et al. 2018). We answer calls for more research on the real effects of corporate taxes (Hanlon and Heitzman 2010) and for research using randomized trials using real economic agents (Floyd and List 2016). By focusing on effects on small firms, we provide new insight on an important but under-researched segment of the economy—a dynamic segment that is vital for economic growth (Neumark et al. 2010) and accounts for the majority of job creation (Haltiwanger et al. 2012). Finally, our results should be of interest to policymakers, who must weigh the benefits of enforcing compliance with the tax laws against the costs of those enforcement efforts.

Notes

We create and examine two measures of firm survival, described in detail later. The first examines whether the firm continues to file tax returns, including adjustments if the owner opens a new business following the audit or converts to an S corporation. We acknowledge that filing a tax return is not a perfect measure of firm survival. The second measure is based on the IRS determining that the firm is defunct after attempting to collect unpaid taxes. This measure is likely a lower-bound estimate of going out of business because only firms that have delinquent tax payments appear in the data.

Our research design follows the approach in Lawrence et al. (2018) where firms are randomly selected from a population for treatment and then closely-matched untreated firms are chosen as control firms. Lawrence et al. (2018) calls this design a field experiment. However, because the IRS’s objective in random audit programs is primarily to estimate the tax gap and not to draw causal inferences, the IRS considers this design to be a stratified random sample of audits.

The results, by themselves, do not suggest the optimality of more or fewer audits. The benefits of a more robust audit system are increased governmental revenues. The value of those benefits depends on how society values goods and services provided by government revenue (i.e., the optimal size of government). The optimal size of government is outside the scope of this paper.

Indeed, Gleason and Mills (2002) find evidence that firms are reticent to disclose contingent tax liabilities (taxes owed following an audit), even when the amounts at stake are material. Their results suggest that studying audits based on firms’ self-disclosure of being audited will likely result in many firms that were audited being misclassified as not having been audited.

There are significant outliers in terms of audit close dates. By the end of 2014, 96% of these audits were completed.

We are not permitted to disclose the industries of the actual firms selected for NRP audit.

Total receipts were defined by the IRS for purposes of the NRP. Total receipts are calculated as the sum of gross receipts, dividend income, interest income, gross rents, royalty income, capital gains, and other income.

We acknowledge some of the shortcomings of PSM, such as its failure to meet the covariate balance condition (King and Nielsen 2019). As a robustness test, we also employ entropy balancing and find consistent results. We discuss this and our preference for the PSM results in Section 6.2.

See https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/the-examination-audit-process for details on the DIF.

See, for example, the 2018 Instructions to Form 1120 (page 2), which state, “Unless exempt under section 501, all domestic corporations (including corporations in bankruptcy) must file an income tax return whether or not they have taxable income.” Section 501 relates to tax-exempt entities, such as charities, churches, and colleges.

We adopt a conservative approach in adjusting for EIN applications by considering any new EIN application as evidence that the original firm has not failed. In untabulated analysis, we restrict this adjustment to only reflect new EIN applications in similar industries to the original firm’s. Our main inferences in that specification are unchanged, but the magnitude of the effect of an IRS audit is larger.

To be more specific, firms are assigned to a “queue” and not directly to a revenue agent. Firms are prioritized and then selected from the queue based on a number of factors, including the amount of unpaid taxes.

We do not provide descriptive statistics for the DIF score due to its proprietary nature.

The main conclusions are robust to estimation with logit and probit models.

The main conclusions are robust to including control variables, and we include this primary specification with control variables in Appendix 2.

The median audit adjustment is zero, meaning this partition is equivalent to partitions on previous compliance or noncompliance.

The decision to be a C corporation or flow-through entity depends on a number of factors, and interested readers can consult Erickson et al. (2020) for details. In an S corporation conversion, for example, firms that have already operated as C corporations face an additional tax if they convert to S corporation status, and thus the C vs. S decision is more complicated for existing C corporations than it is for new firms. Specifically, there is a tax on built-in gains when converting from a C corporation to an S corporation.

References

Angrist, J., and J.S. Pischke. 2014. Mastering ‘metrics. Princeton University Press.

Ayers, B.C., J.K. Seidman, and E. Towery. 2019a. Taxpayer behavior under audit certainty. Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (1): 326–358.

Ayers, B.C., J.K. Seidman, and E.M. Towery. 2019b. Taxpayer behavior under audit certainty. Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (1): 326–358.

Beaver, W.H., M. Correia, and M.F. McNichols. 2011. Financial statement analysis and the prediction of financial distress. Foundations and Trends® in Accounting 5 (2): 99–173.

Belnap, A. 2019. The effect of public scrutiny on mandatory and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.17615/3an5-av92

Blaylock, B.S. 2016. Is tax avoidance associated with economically significant rent extraction among U.S Firms? Contemporary Accounting Research 33 (3): 1013–1043.

Coglianese, C., A.M. Finkel, and C. Carrigan. 2014. Does regulation kill jobs? Press.

Congressional Budget Office. 2020a. H.R. 266, Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, As passed by the Senate on April 21, 2020, Cost Estimate.

Congressional Budget Office. 2020b. Preliminary Estimate of the Effects of H.R. 748, the CARES Act, Public Law 116–136, Revised, With Corrections to the Revenue Effect of the Employee Retention Credit and to the Modification of a Limitation on Losses for Taxpayers Other Than Corporations.

DeBacker, J., B.T. Heim, A. Tran, and A. Yuskavage. 2015a. Legal enforcement and corporate behavior: An analysis of tax aggressiveness after an audit. The Journal of Law and Economics 58 (2): 291–324.

DeBacker, J., B.T. Heim, A. Tran, and A. Yuskavage. 2018. The effects of IRS audits on EITC claimants. National Tax Journal 71 (3): 451–484.

Desai, M.A., A. Dyck, and L. Zingales. 2007. Theft and taxes. Journal of Financial Economics 84 (3): 591–623.

Edwards, A., C. Schwab, T. Shevlin. 2013. Financial constraints and the incentive for tax planning. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2163766

El Ghoul, S., O. Guedhami, and J. Pittman. 2011. The role of IRS monitoring in equity pricing in public firms. Contemporary Accounting Research 28 (2): 643–674.

Erickson, M.M., M.L. Hanlon, E.L. Maydew, and T.J. Shevlin. 2020. Taxes and business strategy. 6th edition. Prentice Hall.

Finley, A.R. 2019. The impact of large tax settlement favorability on firms’ subsequent tax avoidance. Review of Accounting Studies 24 (1): 156–187.

Floyd, E., and J.A. List. 2016. Using field experiments in accounting and finance. Journal of Accounting Research 54 (2): 437–475.

Gleason, C.A., and L.F. Mills. 2002. Materiality and contingent tax liability reporting. The Accounting Review 77 (2): 317–342.

Gow, I.D., D.F. Larcker, and P.C. Reiss. 2016. Causal inference in accounting research. Journal of Accounting Research 54 (2): 477–523.

Guala, F., and L. Mittone. 2005. Experiments in economics: External validity and the robustness of phenomena. Journal of Economic Methodology 12 (4): 495–515.

Guedhami, O., and J. Pittman. 2008. The importance of IRS monitoring to debt pricing in private firms. Journal of Financial Economics 90 (1): 38–58.

Haltiwanger, J., R.S. Jarmin, and J. Miranda. 2012. Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. The Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (2): 347–361.

Hanlon, M., and S. Heitzman. 2010. A review of tax research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2): 127–178.

Hanlon, M., J.L. Hoopes, and N. Shroff. 2014. The effect of tax authority monitoring and enforcement on financial reporting quality. The Journal of the American Taxation Association 36 (2): 137–170.

Hanlon, M., L.F. Mills, and J. Slemrod. 2007. An empirical examination of corporate tax noncompliance. In taxing corporate income in the 21st century, edited by A. J. Auerbach, J. R. Hines, and J. Slemrod, 171–210. Cambridge University press.

Hoopes, J.L., D. Mescall, and J.A. Pittman. 2012. Do IRS audits deter corporate tax avoidance? The Accounting Review 87 (5): 1603–1639.

Internal Revenue Service. 2017. Internal Revenue Service 2017 Databook.

Internal Revenue Service. 2021. Taxpayer First Act: Report to Congress.

Kerr, J. N. 2012. The real effects of opacity: Evidence from tax avoidance. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2234197

King, G., and R. Nielsen. 2019. Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Political Analysis 27 (4): 435–454.

Larcker, D.F., and T.O. Rusticus. 2010. On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 49 (3): 186–205.

Law, K., and L.F. Mills. 2014. Taxes and financial constraints: Evidence from linguistic cues. Journal of Accounting Research 53 (4): 777–819.

Lawrence, A., J. Ryans, E. Sun, and N. Laptev. 2018. Earnings announcement promotions: A yahoo finance field experiment. Journal of Accounting and Economics 66 (2): 399–414.

Lennox, C.S., J.R. Francis, and Z. Wang. 2012. Selection models in accounting research. The Accounting Review 87 (2): 589–616.

Li, W., J. Pittman, Z.-T. Wang. 2018. The determinants and consequences of tax audits: Some evidence from China. The Journal of the American Taxation Association. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2585466

Lisowsky, P., and M. Minnis. 2020. The silent majority: Private U.S. firms and financial reporting choices. Journal of Accounting Research 58 (3): 547–588.

List, J.A. 2011. Why economists should conduct field experiments and 14 tips for pulling one off. Journal of Economic Perspectives 25 (3): 3–16.

Mahon, J., E. Zwick. 2014. The role of experts in fiscal policy transmission.

Mills, L.F. 1998. Book-tax differences and internal revenue service adjustments. Journal of Accounting Research 36 (2): 343–356.

Mills, L.F., and R.C. Sansing. 2000. Strategic tax and financial reporting decisions: Theory and evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research 17 (1): 85–106.

Minnis, M. 2011. The value of financial statement verification in debt financing: Evidence from private U.S. firms. Journal of Accounting Research 49 (2): 457–506.

Mittone, L. 2006. Dynamic behaviour in tax evasion: An experimental approach. The Journal of Socio-Economics 35 (5): 813–835.

National Taxpayers Union. 2016. Statement of Pete Sepp to House Subcommittee Regarding IRS Small Business Reforms.