Abstract

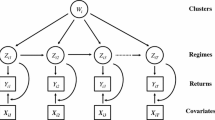

The literature shows that earnings have come to explain less stock price movement over time, suggesting that firm fundamental information has become less important. In this paper, we replace earnings with earnings announcement returns as a measure of firm fundamental news and find that these firm fundamentals have come to explain more price movement over time. In the years after 2003, earnings announcement returns explain roughly 20% of the annual return—almost twice as much as they did before, indicating that fundamental information has become more important, not less, in explaining stock returns. This pattern occurs for other forms of firm fundamental information. Collectively, the returns around earnings announcements, management guidance, analyst forecasts, analyst recommendations, and 8-K filings went from explaining 17% of annual returns on average in the late 1990s to 39% on average in the early 2010s. In exploring possible explanations for the increase in the explanatory power of fundamental information, we find evidence consistent with regulatory changes, such as new 8-K filing requirements and Sarbanes-Oxley, collectively making disclosures more informative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Ball and Shivakumar (2008) examine the R2s from regressions of annual returns on earnings announcement returns and find the abnormal R2 to be between 5% and 9%. They do notice higher values in the last three years of their data, 2004 to 2006, although their limited sample period restricts their ability to draw definitive conclusions. We show that the increase in 2004–2006 is not a temporary shift, but a permanent one. We estimate that earnings announcements contribute about 20% of the year’s price-relevant information after 2004, if we exclude the crisis years of 2008 and 2009. This is substantially higher than the headline estimate of Ball and Shivakumar (2008). We go further and estimate the collective explanatory power of earnings announcements, management guidance, analyst forecasts, analyst recommendations, and 8-K filings, which explain almost 40% of the annual return in recent years. We also explore a number of potential explanations for the recent increase in explanatory and suggest that regulatory changes, such as SOX and new 8-K filing requirements, make disclosed fundamental information more informative.

In an untabulated test, we have verified this by running time-series regressions by firm and examining how much the coefficients vary across firms in the regressions of annual returns on earnings changes or earnings announcement returns. They vary much more for earnings changes than for announcement returns. For the changes in earnings coefficients, the standard deviation is about three times the mean, and the value at the third quartile is about nine times the value at the first quartile. In contrast, for the earnings announcement return coefficients, the standard deviation is about equal to the mean, and the value at the third quartile is only about 3.5 times the value at the first quartile.

These numbers come from our preferred specification, which uses logarithmic returns. We also report results for arithmetic returns.

Kishore et al. (2008) find a stronger post earnings announcement drift when surprise is measured as earnings announcement returns (EAR) than when it is measured by standardized unexpected earnings (SUE). In addition, the EAR and SUE strategies are largely independent. To the extent that subsequent returns are correlated with announcement returns, investor underreaction to EAR and SUE is fully picked up by our R2 approach.

The U-statistic is related to time-series volatility of daily returns, which differs from the cross-sectional variation in annual returns that underlies our R2 measure. Take noise trading (or liquidity trading) as an example. More noise trading exaggerates daily price movements and thus increases the volatility of daily returns, but the impact of noise trading on returns reverses over time and does not affect annual returns. Therefore a reduction in noise trading from year to year will increase the U-statistic but may not affect our R2. Empirically, time-series volatility of daily returns and cross-sectional variance in annual returns exhibit different patterns. Ignoring the periods of the bursting of the Internet bubble and financial crisis, Bartram et al. (2018) show that time-series volatility of daily returns declines over time, whereas our untabulated analysis finds that cross-sectional variance in annual returns is largely flat over time (if anything it increases).

Bird et al. (2017) use the increasing explanatory power of earnings announcement returns as a motivation for their paper, which studies the benefits of accounting regulations. They use firms’ own pre-adoption mentions of accounting standards as a measure of treatment intensity and find that accounting standards increase absolute earnings announcement returns. Consistent with standards reducing discretionary disclosure, they show that this increase is explained by the increasing informativeness of negative earnings news.

We expect earnings announcements to capture more firm-specific information as opposed to market-wide or industry-wide information. Market-wide information tends to be captured by the intercept of our regression and thus does not affect the R2, whereas industry-wide information still affects the R2.

Independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) returns imply either that investors do not value firm fundamental information or that the disclosures do not provide any new information. As a result, returns during earnings announcements resemble those during non-announcement periods.

The literature also uses analyst forecast errors, measured as actual earnings minus the analyst forecast. We stick to earnings changes to preserve our long sample period. However, in untabulated tests, we have found that analyst forecast errors exhibit the same patterns that we find for earnings changes.

We measure annual returns starting three months after the prior fiscal year-end so that they do not include the prior year’s earnings announcements but include the current year’s four earnings announcements.

For this untabulated test, we measure analyst forecast errors as the IBES actual earnings minus the consensus (median) analyst forecast at the beginning of the year (where the beginning of the year means the forecast during the third month of the current fiscal year, which is around the time when the previous-year’s annual report comes out), scaled by average total assets per share from the beginning of the year to the end of the year.

Beaver et al. (2018, 2019) find that the U-statistic increases steadily starting in 2001, rather than in 2004. We find that the R2 had no significant increase in 2001. In an untabulated test, we repeat the regression in Panel C of Table 3 but add an indicator that turns on for the years between 2001 and 2003 (inclusive). The coefficient on this indicator is negative and insignificant.

Specifically, REV(FQ1) is the sum of analyst forecast revisions of next-quarter earnings around the earnings announcements during the firm’s fiscal year. For every firm-quarter, we examine the analyst forecast revision of next-quarter’s earnings from before the current quarter’s earnings announcement to after, scaled by the stock price in the month of the current quarter’s earnings announcement (as recorded by IBES). Then we sum up these revisions over the four quarters in the firm’s fiscal year.

Specifically, ΔRVOL is the standard deviation of daily returns in year t + 1 minus the standard deviation of daily returns in year t.

The regressions with REV(FQ1) on the left-hand-side start in 1984, because that is when we first have a large sample of analyst forecasts from IBES. The regressions with ΔE on the right-hand side end in 2017, because we do not yet have 2019 annual earnings data.

While these explanations are not mutually exclusive, another reason for us to examine regulatory changes is that they have not been examined before, implying greater contribution to the literature.

Even for the 8-Ks’ new information that could have been anticipated from the earnings announcement press releases, any underreaction by investors would make it so that moving the 8-Ks into the earnings announcement windows would increase the R2 in the regression. While the R2 does pick up post-earnings-announcement drift, it only picks up the average (systematic underreaction), so any variation in the underreaction across firms (firm-specific under-reaction) will go to the residual and reduce the R2. We could expect there to be variation in the underreaction to the extent that investors pay different amounts of attention to different firms (Hirshleifer et al. 2009). Moving the 8-Ks into the earnings announcement windows essentially moves such variation to earnings announcement returns and thus increases the correlation between annual returns and earnings announcement returns.

This increase is overcoming the negative impact on earnings informativeness of another 8-K rule, from the same period, which increased the frequency of 8-K disclosures. McMullin et al. (2019) find that the more timely 8-K disclosures from this other rule undermined the information content of earnings announcements.

Consistent with the rule that determines accelerated filer status, we measure market values as of the end of the firm’s second fiscal quarter. We use market values instead of public floats because floats are not available in a machine-readable database.

SOX 404 may have increased the credibility of financial statements and the earnings number itself may remain a poor summary measure for the news provided by financial statements. Earnings could remain a poor summary measure of news because the same magnitude of a change in earnings can have different implications for the future in different contexts. Also, we have shown that earnings have become too noisy to capture the informativeness of firm fundamentals. Chen et al. (2013) find evidence that the information content of earnings increased after the introduction of SOX 404, suggesting that SOX 404 has worked to reduce the noise. However, the impact seems negligible in the face of the overall downward trend we show in Fig. 1.

In untabulated analysis, we further narrow the bandwidth around the $75 million threshold by limiting the sample to firms with market capitalizations greater than $35 million and less than $150 million. We find that the coefficient on D*POST2003 becomes stronger (b3 = 0.065) but statistical significance becomes a little weaker (t = 1.73) because of the smaller sample.

Our percentages of concurrent management guidance are higher than those reported by Rogers and Van Buskirk (2013) and Beaver et al. (2019), because they separately examine each earnings announcement, whereas we examine firm-years and count a firm-year as having concurrent guidance if at least one of its earnings announcements does.

The percentage of firms with bundled guidance is about zero prior to 1995. In both 1993 and 1994, the first two years we have manager guidance data, less than 10 firms are included in the group with bundled management guidance.

Ball and Shivakumar (2008) also examined this with their limited sample period and determined that management forecasts could not explain the increase in the last three years of their sample.

References

Alexander, C.R., S.W. Bauguess, G. Bernile, Y.A. Lee, and J. Marietta-Westberg. 2013. Economic effects of SOX section 404 compliance: A corporate insider perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2–3): 267–290.

Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., D.W. Collins, W.R. Kinney Jr., and R. LaFond. 2008. The effect of SOX internal control deficiencies and their remediation on accrual quality. The Accounting Review 83 (1): 217–250.

Ball, R., and P. Brown. 1968. An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers. Journal of Accounting Research: 159–178.

Ball, R., and L. Shivakumar. 2008. How much new information is there in earnings? Journal of Accounting Research 46 (5): 975–1016.

Bartram, S.M., G.W. Brown, and R.M. Stulz. 2018. Why has idiosyncratic risk been historically low in recent years? National Bureau of Economic Research.

Basu, S., T. Duong, S. Market, and E. Tan. 2013. How important are earnings announcements as an information source? European Accounting Review 22 (2): 221–256.

Beaver, W. 1968. The information content of annual earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research 6: 67–92.

Beaver, W., M. McNichols, and Z. Wang. 2018. The information content of earnings announcements: New insights from intertemporal and cross-sectional behavior. Review of Accounting Studies 23 (1): 95–135.

Beaver, W., M. McNichols, and Z. Wang. 2019. Increased information content of earnings announcements in the 21st century: An empirical investigation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 69 (1).

Bekaert, G., R.J. Hodrick, and X. Zhang. 2012. Aggregate idiosyncratic volatility. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 47 (6): 1155–1185.

Beyer, A., D. Cohen, T. Lys, and B. Walther. 2010. The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 296–343.

Bird, A., Karolyi, S.A. and Ruchti, T. 2017. Regulating information. Carnegie Mellon University working paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2854469.

Brown, S., K. Lo, and T. Lys. 1999. Use of R2 in accounting research: Measuring changes in value relevance over the last four decades. Journal of Accounting and Economics 28 (2): 83–115.

Bushman, R., A. Lerman, and X.F. Zhang. 2016. The changing landscape of accrual accounting. Journal of Accounting Research 56 (1): 41–77.

Chen, L.H., J. Krishnan, H. Sami, and H. Zhou. 2013. Auditor attestation under SOX section 404 and earnings informativeness. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 32 (1): 61–84.

Collins, D.W., E.L. Maydew, and I.S. Weiss. 1997. Changes in the value-relevance of earnings and book values over the past forty years. Journal of Accounting and Economics 24 (1): 39–67.

Collins, D., O. Li, and H. Xie. 2009. What drives the increased informativeness of earnings announcements over time? Review of Accounting Studies 14: 1–30.

Core, J.E., W.R. Guay, and A. Van Buskirk. 2003. Market valuations in the new economy: An investigation of what has changed. Journal of Accounting and Economics 34 (1): 43–67.

Dichev, I., and V. Tang. 2008. Matching and the changing properties of accounting earnings over the last 40 years. The Accounting Review 83 (6): 1425–1460.

Francis, J., and K. Schipper. 1999. Have financial statements lost their relevance? Journal of Accounting Research 37 (2): 319–352.

Francis, J., K. Schipper, and L. Vincent. 2002. Expanded disclosures and the increased usefulness of earnings announcements. The Accounting Review 77: 515–546.

Hand, J.R., Laurion, H., Lawrence, A., and Martin, N. 2018. Analyst forecast data feeds are not what they used to be. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill working paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3117122.

Hirshleifer, D., S.S. Lim, and S.H. Teoh. 2009. Driven to distraction: Extraneous events and underreaction to earnings news. The Journal of Finance 64 (5): 2289–2325.

Iliev, P. 2010. The effect of SOX section 404: Costs, earnings quality, and stock prices. The Journal of Finance 65 (3): 1163–1196.

Kinney, W., D. Burgstahler, and R. Martin. 2002. Earnings surprises “materiality” as measured by stock returns. Journal of Accounting Research 40 (5): 1297–1329.

Kishore, R., Brandt, M., Santa-Clara, P., and Venkatachalam, M. 2008. Earnings announcements are full of surprises. Duke University working paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=909563.

Landsman, W., and E. Maydew. 2002. Has the information content of quarterly earnings announcements declined in the past three decades? Journal of Accounting Research 40: 797–808.

Lerman, A., and J. Livnat. 2010. The new form 8-K disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies 15: 752–778.

Lev, B. 1989. On the usefulness of earnings and earnings research: Lessons and directions from two decades of empirical research. Journal of Accounting Research: 153–192.

Lev, B. 2018. The deteriorating usefulness of financial report information and how to reverse it. Accounting and Business Research 48 (5): 465–493.

Lev, B., and P. Zarowin. 1999. The boundaries of financial reporting and how to extend them. Journal of Accounting Research 37 (2): 353–385.

McMullin, J.L., B.P. Miller, and B.J. Twedt. 2019. Increased mandated disclosure frequency and price formation: Evidence from the 8-K expansion regulation. Review of Accounting Studies 24 (1): 1–33.

Prentice, R. 2007. Sarbanes-Oxley: The evidence regarding the impact of SOX 404. Cardozo Law Review 29: 703.

Rogers, J., and A. Van Buskirk. 2013. Bundled forecasts in empirical accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 55 (1): 43–65.

Schroeder, J.H., and M.L. Shepardson. 2015. Do SOX 404 control audits and management assessments improve overall internal control system quality? The Accounting Review 91 (5): 1513–1541.

Schwert, G.W. 2011. Stock volatility during the recent financial crisis. European Financial Management 17 (5): 789–805.

Singer, Z., and H. You. 2011. The effect of section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley act on earnings quality. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 26 (3): 556–589.

Srivastava, A. 2014. Why have measures of earnings quality changed over time? Journal of Accounting and Economics 57 (2–3): 196–217.

Thomas, J., Zhang, F., and Zhu, W. 2020a. Dark trading and post earnings announcement drift. Management Science, forthcoming.

Thomas, J., Zhang, F., and Zhu, W. 2020b. Measuring the information content of disclosures: The role of return noise. Yale University working paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3197745.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Sloan (editor), two anonymous referees, and workshop participants at Drexel University, Duke University, Peking University, Southern Methodist University, Yeshiva University, and the AAA annual meeting for helpful suggestions and comments. Shuai Shao thanks financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71702162) and Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Grant sponsored by Ministry of Education of China (No. 20JZD014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, S., Stoumbos, R. & Zhang, X.F. The power of firm fundamental information in explaining stock returns. Rev Account Stud 26, 1249–1289 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-020-09572-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-020-09572-7