Abstract

Purpose

Long COVID, an illness affecting a subset of individuals after COVID-19, is distressing, poorly understood, and reduces quality of life. The objective of this sub-study was to better understand and explore individuals' experiences with long COVID and commonly reported symptoms, using qualitative data collected from open-ended survey responses.

Methods

Data were collected from adults living with long COVID who participated in a larger observational online survey. Participants had the option of answering seven open-ended items. Data from the open-ended items were analyzed following guidelines for reflective thematic analysis.

Results

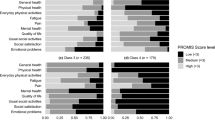

From 213 participants who were included in the online survey, 169 participants who primarily self-identified as women (88.2%), aged 40–49 (33.1%), who had been experiencing long COVID symptoms for ≥ 6 months (74%) provided open-ended responses. Four overlapping and interconnected themes were identified: (1) Long COVID symptoms are numerous and wearing, (2) The effects of long COVID are pervasive, (3) Physical activity is difficult and, in some cases, not possible, and (4) Asking for help when few are listening, and little is working.

Conclusion

Findings reaffirm prior research, highlighting the complex nature of long COVID. Further, results show the ways individuals affected by the illness are negatively impacted and have had to alter their daily activities. Participants recounted the challenges faced when advocating for themselves, adapting to new limitations, and navigating healthcare systems. The varied relapsing–remitting symptoms, unknown prognosis, and deep sense of loss over one's prior identity suggest interventions are needed to support this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The acute impact of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) infection varies widely, with some individuals experiencing no symptoms and others experiencing adverse effects that vary from mild to critical severity [1, 2]. Diverse responses to COVID-19 persist beyond the initial presentation, with a subset of the population experiencing complicated, disconcerting, prolonged illness [3], widely known as long COVID [4] (or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection). Though much remains unknown, long COVID is characterized by multiorgan impairments that span respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, dermatological, and gastrointestinal systems [5]. Commonly reported symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, dry cough, cognitive impairment, headache, heart palpitations, chest tightness, and dizziness [6,7,8]. Symptoms can co-occur, vary in severity, and be cyclical or episodic in nature [9, 10]. Initially, the prevalence and seriousness of chronic symptoms after COVID-19 were underrecognized, contested, or dismissed [11, 12], and much of the early research on long COVID was led by patients [8]. Researchers and healthcare providers worldwide now recognize the significant burden and detrimental impacts on quality of life associated with long COVID [13, 14].

Nevertheless, there is still a relatively poor understanding of the lived experience of long COVID. For example, much of the early evidence describing long COVID came from individuals who were hospitalized for COVID-19 [15,16,17,18,19] or excluded those without a laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 infection, despite numerous reasons why this may not have been accessible [20]. Furthermore, despite a highly engaged patient population whose activism collectively made long COVID's complex symptomatology visible [4, 8, 21], studies have mainly used quantitative surveys [22], and few studies have included the patient voice through qualitative approaches. Of the studies that have used qualitative approaches [23,24,25,26,27], the patient experience has been explored via interview and focus group methodologies with individuals affected by long COVID residing in the United Kingdom. In these studies, patients offer detailed accounts of navigating skepticism from the healthcare system and their social networks, the challenges of managing inconspicuous symptoms, the inability to perform physical activity or activities of daily living, and the importance of seeking refuge and information from similar others [23,24,25,26,27]. However, few studies have analyzed open-ended survey items using qualitative approaches as a lower burden approach to gathering in-depth information or captured experiences of individuals with long COVID residing outside of the United Kingdom. Although interviews and focus groups can enable researchers to probe and further explore patients' lived experiences, in the case of long COVID, such emotionally, socially, and time-consuming methods could preclude those with the most severe symptoms from participating.

Therefore, using data from a larger online survey conducted in 2021, the specific objective of this sub-study was to better understand and explore individuals' experiences with long COVID and commonly reported symptoms using qualitative data collected from open-ended survey items.

Methods

The qualitative data reported herein were collected as part of a larger observational study using an online survey [7], which was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB21-0159). Initially, the qualitative data were collected to enable participants to qualify or elaborate on their closed-ended responses, with planned content analysis if data were sufficient. However, upon exporting the qualitative data, it became apparent that rich and important insights were offered and that in-depth reflexive thematic analysis [28] of this survey data [29] was warranted. A pragmatic approach [30] and constructivist paradigm [31] were adopted, wherein participants' voices were centered and reality was viewed as varied and socially created.

Participants

Individuals were eligible if they could read and understand English and self-identified as (1) an adult aged ≥ 18 years; (2) currently experiencing long-term symptoms due to COVID-19 (at least 4 weeks since the acute illness or positive COVID-19 test, with symptoms not pre-dating the acute illness); and (3) having tested positive for COVID-19, or with probable infection (based on an illness mimicking the acute phase of COVID-19, having close contact with a confirmed case, or being linked with an outbreak), in line with the clinical case definition post-COVID-19 condition [32].

Procedures

Individuals were recruited internationally between February and April 2021 from long COVID networks on social media (Twitter and Facebook). The study team shared a recruitment slide (i.e., advertisement) with community leaders, patient advocates, and patient support groups (where permission was granted) via these social networks. In addition, the study team shared the slide with their network of physiotherapy/rehabilitation professionals. A snowball recruitment strategy was also used to allow patients and clinicians to identify other people living with long COVID. Advertisements included a link that took potential participants to a page where they could read information about the study and review the eligibility criteria before being directed to provide informed consent. Following consent, participants gained access to the secure online survey housed on Qualtrics.

Measures

The larger online survey consisted of a socio-demographic and medical questionnaire, five closed-ended questionnaires assessing fatigue, post-exertional malaise, health-related quality of life, breathing discomfort, and physical activity (described and presented elsewhere [7]), and seven open-ended items. The seven open-ended items, which are the focus of this manuscript, were presented after each of the five closed-ended questionnaires, or block of questions, via stems such as "Please use this space for any other comments about your experience with symptoms that continued or developed after acute COVID‑19, or the support you have received for long COVID. This is optional, please skip this question if you have no other comments." The survey took approximately 30 min to complete (29.2 ± 17.1 min), and responses to open-ended questions ranged from 5 to 290 words.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for socio-demographic and medical data using Jamovi [33]. Open-ended qualitative data were de-identified, transferred to an Excel spreadsheet, and uploaded to be managed in NVivo (QSR International; 12.6.1). Following guidelines for reflexive thematic analysis [28], two authors (AW, RT) independently familiarized themselves with the data by reading the responses several times. Next, data were coded inductively by a single author (AW) who identified salient features within responses to generate initial codes. Salient features were determined based on their relevance to the topic, this sub-study's objectives, and the author's judgment. Similar codes were then grouped together into subthemes and main themes that summarized the raw data and conveyed the salient features. At this point, two authors (AW, RT) convened to review the subthemes and main themes and to challenge one another's interpretations of the data and explore alternative perspectives. The authors also reviewed the themes to check for internal homogeneity (i.e., data within themes fit together meaningfully) and external heterogeneity (i.e., clear distinctions between themes). A theme table including representative quotes was generated, iterated upon, and circulated to a patient partner and the third author (KF) to critically review. Following this, the three authors (AW, KF, RT) met to further discuss and challenge one another's understanding of and experience with the data (see Supplementary File 1 for the authors' reflexivity statement). The theme table was then finalized and sent to all authors to review.

Several strategies were employed to ensure sensitivity to the context, commitment and rigor, transparency and coherence, and impact and importance [34]. For example, the authors sought to ask and answer an important, practical, and timely research question and recruited a sample who could provide firsthand accounts. As well, the stages of the research process have been concisely presented above to elucidate the iterative and reflexive nature of the data collection and analysis process and to enhance transparency. Finally, representative quotes are included herein, and a table was generated so that readers may review and critically reflect upon the authors' interpretations.

Patient involvement

Within the larger study, a patient partner was involved (March 2021 onward) and contributed to the interpretation of the results. For this sub-study, the same patient partner contributed to data analysis and interpretation. The patient partner and co-author (KF) critically reviewed and reflected on the theme table and was actively engaged in iterative discussions, aiding the interpretation of findings. The patient partner also contributed to three team meetings (60–75 min each) to discuss the research objectives, review subthemes and themes, and comment on (and approve of) the final version of the manuscript.

Results

Of the 213 participants who were included in the larger study, 169 (79%) provided responses to the open-ended items and were included herein. Of note, most (n = 105; 62%) provided responses to three or more of the open-ended items. The remaining (n = 64; 38%) responded to one or two open-ended items.

Participants

The socio-demographic and medical characteristics of participants in this sub-study are presented in Table 1. Most participants identified as women (88.2%), and were aged 30–39 (21.3%), 40–49 (33.1%), or 50–59 (23.1%). The majority identified as White (93.5%) and from Canada (37.3%), the United Kingdom (39.6%), or the United States of America (15.4%). Most participants (58.6%) described managing long COVID symptoms for more than 10 months. Visual comparison of participants in this sub-study and the larger study suggested the samples were similar.

Main results

Participants' insights into their long COVID experience and commonly reported symptoms are summarized across four overlapping themes and eight subthemes, which are described below. Table 2 contains representative quotations associated with each theme and subtheme. To respect participant confidentiality, the larger online survey was anonymous, and any potentially identifying information was redacted. Spelling and grammar were edited for readability, and where necessary, additional descriptive information was added, which is presented within square brackets.

Long COVID symptoms are numerous and wearing

This theme captures when participants described the nature of their illness and its symptoms.

Symptoms are numerous

Participants described navigating a wide range of symptoms. For many, the sheer volume of symptoms was described as overwhelming and unmanageable. Indeed, while some participants attempted to list each of their symptoms, many indicated it was far too many to count. Others only described select (or few) symptoms.

‘Common’ long COVID symptoms

In response to open-ended items asking about some of the more commonly reported long COVID symptoms (fatigue, post-exertional malaise, shortness of breath), most participants shared that they experienced high levels of fatigue. Participants explained how their fatigue was so much more than being tired. They described it as unrelenting and unlike anything else they had ever experienced. Of note, few participants described little or no fatigue but went on to share their experiences with other 'common' long COVID symptoms (e.g., post-exertional malaise). Participants also shared that post-exertional malaise was experienced often and was seemingly triggered by a wide range of activities, from physical activity to cognitive tasks. Finally, participants shared their variable breathing challenges, which ranged in severity and impact on day-to-day functioning. While many described the debilitating nature of their breathing challenges, others indicated that shortness of breath had not been among their most concerning symptom(s).

Symptoms vary in presentation and intensity

Participants offered their perspectives on the nature of long COVID when they recounted navigating relapsing and remitting symptoms. For most, symptom presentation was described as completely unpredictable and puzzling. In these cases, participants described how their symptoms would relapse and remit, often seemingly at random. For others, symptoms did not cycle through increasing and decreasing severity. Instead, their symptoms remained heightened or tapered off as they slowly returned closer to their prior level of functioning.

The effects of long COVID are pervasive

This theme captures when participants mentioned noticing marked changes in their functional capacity and ability to maintain their responsibilities and roles. Consequently, participants described the many ways they modified their day or accepted being unable to complete necessary activities of daily living.

Modified sense of self

The debilitating impact of long COVID on participants' lives (whether short- or long-term) was made apparent and discussed as a major concern. Participants expressed a deep sense of loss over their changed health, functional capacity, and overall reduced quality of life. Many expressed feeling trapped or stuck within a disabled body that they no longer recognize or understood, which was described as frustrating and scary. Of note, few participants did not share in this experience. In these cases, participants described enjoying not needing to be physically active or that their symptoms were improving and they were (very) slowly re-integrating into some of their prior activities.

Changed capacity to manage roles and responsibilities

Participants indicated they could no longer take care of their home, families, and in some cases, themselves because of their symptoms. For many participants, their current functional capacity stood in stark contrast to their life before COVID-19. Participants also described that despite social opportunities being limited due to physical distancing restrictions, they are still unable to manage engaging in, or thinking about, being social. Being unable to manage their day-to-day life was described by participants as extremely upsetting and distressing.

Changed capacity to work

Most participants within this sample wrote that they were not working or had greatly reduced the hours within their workweek to help manage their long COVID symptoms. For those participants who were not currently working, concerns over lost income and/or being dismissed were prevalent. For those participants who were working, many described phased returns to work (that were gentle and progressed slowly), needing modified schedules, working from bed or the couch, being depleted after work and on their days off, or the setbacks they were facing along the way.

Physical activity is difficult, and in some cases, not possible

This theme captures when participants wrote about changing their physical activity behavior as a result of post-exertional malaise or symptoms during physical activity. Participants expressed a sense of loss over their pre-COVID physical activity behavior. Some participants expressed deep-seated fears of engaging in more physical activity in case it worsened their symptoms and caused further setbacks, which was underlined by a sense of deteriorating trust in their own bodies. While some participants described reintroducing physical activity, the slow, adapted nature of their 'new' movement routine was described as standing in stark contrast to their prior capacity.

Asking for help when few are listening, and little is working

This theme captures when participants described the support (or lack thereof) they received from the healthcare system. Participants expressed a desire to be heard and taken seriously and to be helped. Further, participants described what they had done/tried to minimize symptoms, whether under guidance from their healthcare team or alternative sources.

Support received

While some participants in this sample felt supported by their healthcare provider, this was viewed as the exception rather than the norm. Indeed, the vast majority of participants recounted being ignored or dismissed by their primary healthcare providers. This left most participants feeling defeated, helpless, invisible, or frustrated. However, participants described still needing care, and many continued to advocate for themselves, despite their symptoms. Participants used the space within the open-ended items in this sub-study to ask, and in some cases, beg for help.

Few, if any, treatments work

Participants described what they have done (or are doing) to minimize their symptoms. Unfortunately, many described their symptoms as persisting regardless of their attempts to find treatment(s). While some participants were of the opinion that pharmacological (e.g., medication) and non-pharmacological options (e.g., diet, physiotherapy) could offer minor relief from symptoms, for others, no treatment(s) had yet offered a reprieve.

Discussion

The purpose of this sub-study was to better understand and explore individuals' experiences with long COVID and commonly reported symptoms using qualitative data collected from open-ended survey items contained within a larger survey [7]. Findings support initial research, which took place during or shortly after the first wave of the pandemic in the United Kingdom with individuals affected by long COVID who were predominantly healthcare professionals [23,24,25,26,27]. Results align with the vexing experience of navigating an 'invisible' and poorly understood illness that disrupts nearly all aspects of daily living and reduces quality of life that have been described previously [23,24,25,26,27]. Thus, this study reaffirms a small evidence base, extending these earlier findings with a larger sample from predominantly developed countries who have been living with long COVID for more than 10 months. This study and those it builds upon [21, 23,24,25,26,27] call for continued efforts to better understand and improve care for individuals with long COVID.

Participants in this sample described their new capacity as being discordant with their physical, occupational, and social obligations. This dissonance manifested as feelings of deep loss, sadness, and frustration. Mourning over one's pre-illness identity and ability to participate in roles, responsibilities, and leisure pursuits has been reported previously with individuals affected by long COVID [27] and other chronic conditions, including fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) [35,36,37,38]. Participants also offered insights into how they have altered their day-to-day life to account for their reduced capacities and possible continued deterioration. For example, some participants described sacrificing social activities to keep up at work; others had to leave work altogether or were fearful of termination; whereas others chose to engage in one task per day or to take breaks after every activity. These findings align with the recent conceptualization of long COVID as characterized by health-related challenges or episodic disability [39, 40]. Looking ahead, exploring if and how individuals adapt to their post-illness body will be necessary. For example, post-exertional malaise can greatly limit the ability to engage in activities that could otherwise help prevent low mood and feelings of isolation [41]. When combined with severe functional limitations and the burden of educating others, there can be serious adverse impacts on mental health [41, 42]. A deeper exploration of common symptoms, including post-exertional malaise, and their physical and psychological consequences, could disentangle the effects of long COVID from the secondary impacts on mental health—ultimately informing interventions and supportive care strategies. For example, mixed-methods approaches may afford participants the opportunity to clarify which symptoms and side effects they consider to be central features of long COVID and which they consider to be secondary consequences.

There were multiple and varied ways participants described self-managing their condition, from consuming medical information and advocating for themselves to adhering to treatments that do not always offer relief. Participants also shared the additional challenge they faced in self-managing their condition within a system that challenged or contested their diagnosis. This sentiment of navigating one's condition amidst doubts about authenticity has been reported in individuals with ME/CFS [43,44,45,46,47]. ME/CFS can occur after an infectious illness such as mononucleosis [48], but it remains a highly stigmatized health condition where patients are vulnerable to epistemic injustice in healthcare encounters [45]. The feelings of dismissal from healthcare providers expressed by participants in this sample, the conceptual ambiguity of both ME/CFS and long COVID, and the nature of symptoms, which are numerous and hard to describe, may result in low credibility being given to the patient testimonial [45]. The recent recognition of long COVID as an outcome of COVID-19 infection (for example, through being given a clinical case definition by the World Health Organization [32]) may help further legitimize the illness. Considering that long COVID may lead to ME/CFS for some patients [49], an important next step is educating primary healthcare providers, who are the front line for patients, to recognize and validate their patients' experiences. Beyond this, equipping healthcare providers with evidence-based guidelines and referral pathways is necessary to better support a growing patient population as they adapt to long COVID.

Finally, there is a critical need to identify appropriate interventions and treatments for those affected by long COVID, which may be best accomplished by including patients as partners in intervention development, implementation, and evaluation. Anecdotally, some individuals with long COVID are responding well to self-management, including activity pacing over extended time periods. Given that typical rehabilitation timeframes are often 2–3 months, and existing rehabilitation approaches (such as pulmonary rehabilitation) are unlikely to be suitable for the majority of people with long COVID, given the distinct clinical presentations [50], novel approaches will be necessary. For example, people with long COVID can have different clusters of symptoms, including predominantly respiratory symptoms or predominantly fatigue-related symptoms [49]. In patients with predominantly fatigue-related symptoms, pulmonary rehabilitation does not target and may exacerbate fatigue. Multidisciplinary, tailored interventions that leverage peer support may be most effective and should adhere to the recommended quality standards of being evidence-based, accessible, and of minimal burden [24, 25]. Rehabilitation specialists who have expertise and experience working with people who have been discredited in the past (e.g., fibromyalgia, ME/CFS, or other chronic conditions resulting in drastically changed capacity or disability) may be best placed to work with patients to design appropriate and effective interventions. Appropriate training of all professionals working with people with long COVID may enhance continuity of care and offer prolonged support for this cohort (as opposed to the often-disconnected care pathways). Engaging with patients and learning from their experiences represent a valuable first step toward improving training and care.

Considerations

First, as acknowledged in the larger study [7], online questionnaires are subject to selection bias. Thus, the extent to which the sample described herein is representative of the population of people living with long COVID is unknown. Second, this sample primarily self-identified as White women residing in North America or Europe. Capturing the perspectives of people from different backgrounds (especially those from historically marginalized and underrepresented groups) is critical to fully understanding long COVID and its potential range of impacts. Relatedly, this survey was only available in English, meaning the perspectives of non-English speakers were not included, and nearly 40% of the sample was from the United Kingdom despite seeking to explore the experiences of individuals with long COVID residing elsewhere. Thus, there remains a need to explore long COVID experience among individuals with long COVID beyond the United Kingdom and industrialized countries more broadly. Third, participants did not need to have a definitive COVID-19 diagnosis. Fourth, this was an anonymous survey, and therefore, the confirmed or suspected infection with SARS-CoV-2 was self-reported. Despite rigorous data cleaning and the severity of self-reported symptoms as previously reported [7], it is possible that some of the participants do not represent the population of interest. Methods of verification of laboratory-confirmed or probable SARS-CoV-2 infection should be considered and reported in future studies. Fifth, this sub-study collected and analyzed open-ended responses to items presented after closed-ended questions measuring specific outcomes or on specific topics. While it is possible that the open-ended item stems were leading, efforts were made to minimize this. For example, the item stems prompted participants to reflect on their broader experiences and use the space if they had additional insights to share and/or to clarify their responses to closed-ended items. Participants were also reminded that their response to open-ended items was completely optional. Sixth, given the nature of the online survey, there was no opportunity to use probes to gain deeper insights, which limits our understanding of the participants' lived experiences. Nevertheless, the authors felt that the benefits of using online open-ended items (i.e., collating a large number of firsthand accounts, low participant burden, anonymity) outweighed these considerations and aligned with the pragmatic approach adopted wherein a balance was sought between advancing conceptualizations of long COVID, and sharing evidence to support this population in real-time.

Conclusion

Given the uncertain nature, and recency of long COVID, exploring individuals' lived experiences is paramount. Findings supplement a relatively small evidence base and reiterate that long COVID is complex and distressing for those affected. The varied relapsing–remitting symptoms, unknown prognosis, and deep sense of loss over one's prior identity suggest interventions are needed to support this population. Further, results underscore the challenges individuals affected by long COVID face when advocating for themselves and adapting to their illness during the pandemic and amidst healthcare systems that are understaffed, at times disbelieving or unarmed (as of yet) with comprehensive treatment guidelines. More research is needed to identify and address the pathophysiology, capture the consequences of long COVID, implement strategies to support those affected, and ultimately better help this cohort navigate the process of adapting to long COVID.

References

Zaim, S., Chong, J. H., Sankaranarayanan, V., & Harky, A. (2020). COVID-19 and multiorgan response. Current Problems in Cardiology, 45, 100618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100618

Wiersinga, W. J., Rhodes, A., Cheng, A. C., Peacock, S. J., & Prescott, H. C. (2020). Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. JAMA, 324, 782–793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12839

Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK (2021). Retrieved May 2021 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021

Callard, F., & Perego, E. (2021). How and why patients made Long Covid. Social Science & Medicine, 268, 113426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426

Dennis, A., Wamil, M., Alberts, J., Oben, J., Cuthbertson, D. J., Wootton, D., et al. (2021). Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: A prospective, community-based study. British Medical Journal Open, 11, e048391. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391

NICE. (2020). COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. NICE. Retrieved May 19, 2021, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/chapter/common-symptoms-of-ongoing-symptomatic-covid-19-and-post-covid-19-syndrome#common-symptoms-of-ongoing-symptomatic-covid-19-and-post-covid-19-syndrome

Twomey, R., DeMars, J., Franklin, K., Culos-Reed, S. N., Weatherald, J., & Wrightson, J. G. (2022). Chronic fatigue and post-exertional malaise in people living with long COVID. Physical Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac005

Davis, H. E., Assaf, G. S., McCorkell, L., Wei, H., Low, R. J., Re’em, Y., et al. (2021). Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

Gorna, R., MacDermott, N., Rayner, C., O’Hara, M., Evans, S., Agyen, L., et al. (2021). Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. The Lancet, 397, 455–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32705-7

Brown, D. A., O’Brien, K. K., Josh, J., Nixon, S. A., Hanass-Hancock, J., Galantino, M., et al. (2020). Six lessons for COVID-19 rehabilitation from HIV rehabilitation. Physical Therapy, 100, 1906–1909. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa142

Alwan, N. A. (2020). Surveillance is underestimating the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 396, e24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31823-7

Alwan, N. A. (2021). The teachings of Long COVID. Communication & Medicine, 1, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-021-00016-0

World Physiotherapy. (2021). World physiotherapy response to COVID-19 briefing paper 9. Safe rehabilitation approaches for people living with Long COVID: Physical activity and exercise. World Physiotherapy.

Nalbandian, A., Sehgal, K., Gupta, A., Madhavan, M. V., McGroder, C., Stevens, J. S., et al. (2021). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine, 27, 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

Huang, C., Huang, L., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Gu, X., et al. (2021). 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. The Lancet, 397, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

Group PCC, Evans, R. A., McAuley, H., Harrison, E. M., Shikotra, A., Singapuri, A., et al. (2021). Physical, cognitive and mental health impacts of COVID-19 following hospitalisation—A multi-centre prospective cohort study. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.22.21254057

Sykes, D. L., Holdsworth, L., Jawad, N., Gunasekera, P., Morice, A. H., & Crooks, M. G. (2021). Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: What is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung, 199, 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-021-00423-z

Tabacof, L., Tosto-Mancuso, J., Wood, J., Cortes, M., Kontorovich, A., McCarthy, D., et al. (2022). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome negatively impacts physical function, cognitive function, health-related quality of life, and participation. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 101, 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000001910

Li, J., Xia, W., Zhan, C., Liu, S., Yin, Z., Wang, J., et al. (2021). A telerehabilitation programme in post-discharge COVID-19 patients (TERECO): A randomised controlled trial. Thorax. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217382

Alwan, N. A., & Johnson, L. (2021). Defining long COVID: Going back to the start. Med (N Y)., 2, 501–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.003

Assaf, G., Davis, H., McCorkell, L., et al. (2020). What does COVID-19 recovery actually look like? An analysis of the prolonged COVID-19 symptoms survey by Patient-Led Research Team. Patient Led Research for COVID-19. Retrieved January 2021 https://patientresearchcovid19.com/

Rando, H. M., Bennett, T. D., Byrd, J. B., Bramante, C., Callahan, T. J., Chute, C. G., et al. (2021). Challenges in defining Long COVID: Striking differences across literature, Electronic Health Records, and patient-reported information. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.20.21253896

Kingstone, T., Taylor, A. K., O’Donnell, C. A., Atherton, H., Blane, D. N., & Chew-Graham, C. A. (2020). Finding the “right” GP: A qualitative study of the experiences of people with long-COVID. BJGP Open. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143

Ladds, E., Rushforth, A., Wieringa, S., Taylor, S., Rayner, C., Husain, L., et al. (2020). Persistent symptoms after Covid-19: Qualitative study of 114 “long Covid” patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 1144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06001-y

Ladds, E., Rushforth, A., Wieringa, S., Taylor, S., Rayner, C., Husain, L., et al. (2021). Developing services for long COVID: Lessons from a study of wounded healers. Clinical Medicine, 21, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0962

Taylor, A. K., Kingstone, T., Briggs, T. A., O’Donnell, C. A., Atherton, H., Blane, D. N., et al. (2021). “Reluctant pioneer”: A qualitative study of doctors’ experiences as patients with long COVID. Health Expectations. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13223

Humphreys, H., Kilby, L., Kudiersky, N., & Copeland, R. (2021). Long COVID and the role of physical activity: A qualitative study. British Medical Journal Open, 11, e047632. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047632

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11, 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2020). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

Kelly, L. M., & Cordeiro, M. (2020). Three principles of pragmatism for research on organizational processes. Methodological Innovations, 13, 2059799120937242. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799120937242

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2013). Philosophical assumptions and interpretive frameworks (chapter 2). In J. W. Creswell & C. N. Poth (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry & research design (4th ed.). Sage.

World Health Oganization. (2021). A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Retrieved October 6, 2021 from, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1

The jamovi project. (2021). jamovi (Version 1.6) [Computer Software]. Retrieved January 2021 https://www.jamovi.org

Yardley, L. (2000). Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology & Health, 15, 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008400302

Ashe, S. C., Furness, P. J., Taylor, S. J., Haywood-Small, S., & Lawson, K. (2017). A qualitative exploration of the experiences of living with and being treated for fibromyalgia. Health Psychology Open, 4, 2055102917724336. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102917724336

Alameda Cuesta, A., Pazos Garciandía, Á., Oter Quintana, C., & Losa Iglesias, M. E. (2021). Fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and multiple chemical sensitivity: Illness experiences. Clinical Nursing Research, 30, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773819838679

Bartlett, C., Hughes, J. L., & Miller, L. (2021). Living with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Experiences of occupational disruption for adults in Australia. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1177/03080226211020656

Sandhu, R. K., Sundby, M., Ørneborg, S., Nielsen, S. S., Christensen, J. R., & Larsen, A. E. (2021). Lived experiences in daily life with myalgic encephalomyelitis. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84, 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022620966254

Brown, D. A., & O’Brien, K. K. (2021). Conceptualising long COVID as an episodic health condition. BMJ Global Health, 6, e007004. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007004

O’Brien, K. K., Bayoumi, A. M., Strike, C., Young, N. L., & Davis, A. M. (2008). Exploring disability from the perspective of adults living with HIV/AIDS: Development of a conceptual framework. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 6, 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-76

Chu, L., Elliott, M., Stein, E., & Jason, L. A. (2021). Identifying and managing suicidality in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Healthcare, 9, 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060629

Devendorf, A. R., McManimen, S. L., & Jason, L. A. (2020). Suicidal ideation in non-depressed individuals: The effects of a chronic, misunderstood illness. Journal of Health Psychology, 25, 2106–2117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318785450

McManimen, S., McClellan, D., Stoothoff, J., Gleason, K., & Jason, L. A. (2019). Dismissing chronic illness: A qualitative analysis of negative health care experiences. Health Care for Women International, 40, 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1521811

McManimen, S. L., McClellan, D., Stoothoff, J., & Jason, L. A. (2018). Effects of unsupportive social interactions, stigma, and symptoms on patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Community Psychology, 46, 959–971. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21984

Blease, C., Carel, H., & Geraghty, K. (2017). Epistemic injustice in healthcare encounters: Evidence from chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Medical Ethics, 43, 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103691

Bayliss, K., Goodall, M., Chisholm, A., Fordham, B., Chew-Graham, C., Riste, L., et al. (2014). Overcoming the barriers to the diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome/ME in primary care: A meta synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Family Practice, 15, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-44

Bayliss, K., Riste, L., Fisher, L., Wearden, A., Peters, S., Lovell, K., et al. (2014). Diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis in black and minority ethnic people: A qualitative study. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 15, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423613000145

Jason, L. A., Yoo, S., & Bhatia, S. (2021). Patient perceptions of infectious illnesses preceding myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Chronic Illness. https://doi.org/10.1177/17423953211043106

Komaroff, A. L., & Bateman, L. (2021). Will COVID-19 lead to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome? Frontiers in Medicine. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.606824

Whitaker, M., Elliott, J., Chadeau-Hyam, M., Riley, S., Darzi, A., Cooke, G., et al. (2021). Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a random community sample of 508,707 people. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.28.21259452

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to sincerely thank the people living with long COVID who took part in this study for sharing their experiences.

Funding

This study was not funded. However, AW was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship and an Alberta Innovates Health Solutions Fellowship during data analysis and manuscript preparation. RT was supported by the O'Brien Institute of Public Health and Ohlson Research Initiative, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship during this study. JGW was supported by the Hotchkiss Brain Institute and the Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary. NCR was funded by the Canadian Cancer Society and Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AW contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, and writing—original draft. JDM and JGW contributed to conceptualization, writing—review, and editing. KF contributed to patient partner (provided guidance based on the lived experience of long COVID), Validation, writing—review, and editing. SNCR contributed to writing—review and editing. RT contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing, and project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

JDM is a physiotherapist and owner of Breath Well Physio (Alberta, Canada) and has been treating people living with long COVID in private practice since July 2020. JDM and RT run a virtual program for people living with long COVID in Alberta, Canada, in collaboration with Synaptic Health (Registered Charity No. 830838280RR001). JDM delivered a paid course for rehabilitation professionals working with people with long COVID in April 2021. The authors have no other conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wurz, A., Culos-Reed, S.N., Franklin, K. et al. "I feel like my body is broken": exploring the experiences of people living with long COVID. Qual Life Res 31, 3339–3354 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03176-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03176-1