Abstract

The objective of this study was to develop and validate a measure called the Tele Attitude Scale (TAS). This measure aims to evaluate relevant aspects of the teleworking experience related to its perceived effects regarding, for instance: job characteristics, perceived productivity, quality of work-related interactions, work-non-work balance, and well-being. Four studies were conducted between 2021 and 2022. First, a qualitative study was conducted to develop the scale (N = 80). Afterward, a second study to explore the scale’s factorial structure (N = 602) was developed. A third study served to analyze its internal validity and reliability (N = 232). A fourth study analyzed the criterion validity of the scale by exploring its correlations with measures of health, affect, and performance (N = 837 teleworkers). The findings revealed that the 10-item scale accounted for a unique factor and that it was a reliable measure. Moreover, the results also showed that the scale was significantly related to measures of health, affect, and performance, thus supporting its convergent and criterion validity. This research advances the knowledge about telework by proposing a user-friendly scale to measure teleworking, specifically how workers perceive their experience of it and how it may impact them at several levels. Thus, the TAS can not only fill a gap in the research but also help organizations evaluate and support teleworkers’ needs and subsequent satisfaction while teleworking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Telework is not a new organizational practice; however, since the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, it has been increasingly adopted. It was originally proposed by Jack Nilles, in 1973, who defined it as a model of work that allows workers to work from their homes, or other locations, using Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). In several economic sectors, organizations are adopting this work model due to diverse factors such as employees’ preferences, development of ICTs and the reduction of costs and increased availability, work-life balance issues, a tendency toward outsourcing activities, changes in employment types, less commuting time and pollution, economic pressures in the business environment and unpredictable changes resulting from global competition (Athanasiadou and Theriou 2021; Kerrin and Hone 2001; Taskin & Bridoux, 2010). Moreover, organizations have already recognized that this model of work can be a way to improve work engagement, performance, and happiness (e.g., Ingusci et al., 2022; Junça-Silva 2023; Lunde et al. 2022).

Even though telework has been increasingly recognized as an important strategy to motivate and retain employees (Kazekami 2020), as far as we know, no measure assesses their perception of the telework experience about several aspects of the job (job characteristics), the individual (well-being, work, and non-work balance), and the others, including the team leader (perceived support). Moreover, despite the number of studies that have demonstrated the beneficial aspects of telework, for instance regarding well-being (Bailey and Kurland 2002; Junça-Silva et al. 2022a), these studies were mostly conducted before and during the pandemic crisis – a period with abnormal turbulence and greater uncertainty (Junça-Silva and Silva 2022); hence, studies conducted after this period are crucial to better understand how employees perceive telework under normal circumstances (Biron et al. 2023; Junça-Silva 2023). Lastly, previous studies assessing the experience of teleworking are limited and the measures available have focused on ad-hoc surveys as opposed to validated scales (Anderson et al. 2015; Biron et al. 2023).

Therefore, it is intended that this research might fill this gap by presenting the newly developed Tele Attitude Scale (TAS), a measure created to evaluate the teleworking experience. The composite variable – tele-attitude – can provide a holistic view of teleworking and contribute to knowledge on teleworkers’ perception of this mode of working and also serve as a way to delineate organizational strategies that match workers’ preferences and, simultaneously, support them. This is particularly important, for example, for employees who work better from home, albeit in a hybrid mode, or to increase the perceived support of their superiors if they have some autonomy and flexibility to manage their working schedule, and/or working models, which in turn, may result in higher work-related well-being.

Developing and validating such a measure is relevant for some reasons (Junça-Silva 2023). First, many organizations implemented telework during the pandemic crisis and maintained it after that (Gohoungodji et al. 2023). Second, we are not aware of any measure that assesses how workers perceive telework, nor any measure that provides a holistic overview of the benefits of teleworking from the teleworker’s perspective. Moreover, the TAS can also be helpful to advance knowledge on the science of teleworking and as such can help to predict certain outcomes. Thus, from a theoretical point of view, it seems relevant to understand the teleworkers’ perspective regarding the main benefits that this flexible working regimen may have. Only when one understands how employees feel and perceive telework, one can design effective strategies to adopt or limit telework (Šmite et al. 2023). As such, from an applied perspective, organizations and managers may benefit from a measure that assesses how their workers perceive and experience teleworking regarding well-being, productivity, work-non-work balance, work-related interactions, and job characteristics. Further, the TAS clarifies potential issues related to how teleworkers experience teleworking, helping organisations to identify strategies that may improve their work-related well-being while teleworking.

2 The concept of telework

The precursors of modern telework can be traced back to 1857, when Edgar Thompson, a business owner in the United States, discovered that he could use a private telegraph system to manage teams that could not be physically together (Grant et al. 2018). Later, in the 1950s, remote work received greater attention from organizations, when communication and information technologies were developed further (Bailey and Kurland 2002). Coupled with technological development, there were changes in the labour market due to the oil crisis that hit the United States in the 70s. It had significant repercussions worldwide, forcing the implementation of strategies, such as the development of programs that would lead to saving energy (Nilles, 1997). In this way, Nilles, in 1997, proposed the reduction of home-work trips, giving rise to the substitution of physical displacement, by the transmission of information.

Nilles (1975) proposed the terms telecommuting and teleworking to contextualize telework. The difference is that teleworking is more comprehensive than telecommuting, since teleworking means any form of work, through information technologies, other than in the workplace, which can be from any point (e.g., home, or another branch of the company; Nilles, 1998). On the other hand, telecommuting just means working from home, without any kind of displacement (Grant et al. 2019). Telework is also different from remote work, e-work, or agile work (Gillies 2011). All of these refer to the ability to work flexibly using remote technology to communicate with the workplace (Grant et al. 2019); and thus replace the physical commute to work (Kazekami 2020).

Telework has been identified as a well-established organizational practice, associated with autonomy, flexibility, and agility in business management (Gálvez et al. 2020; Charalampous et al. 2022). Indeed, the purpose of teleworking was, firstly, to offer an effective response to organizations to face market pressures and, secondly, to constitute a key element for the strategic development of organizations (Meier et al. 2023). Adopting telework, within the recommended standards, should become an instrument that benefits the company, the employee, and society (Eurofound 2017).

Recent research has shown that teleworking has benefits not only for employees (e.g., satisfaction) but also for organizations (e.g., productivity) (e.g., Buomprisco et al. 2021; De Vries et al. 2019; Lopes et al. 2023). Indeed, teleworking has been associated with flexible approaches to work, a higher balance between work and non-work domains, and improved well-being (Grant et al. 2019; Lunde et al. 2022), in part due to the absence of commuting time that may be spent in other domains (e.g., family activities, pets), and also to the autonomy and flexibility that teleworking promotes (e.g., De Vries et al. 2019; Grant et al. 2013; 2019).

Notwithstanding, there are also studies showing that teleworking may also have pervasive effects such as decreased satisfaction, and social interaction, work overload, and more interruptions during work (e.g., virtual meetings) that could, in turn, influence workers’ performance due to their over-working and the pressure exerted on them (e.g., Barber and Santuzzi 2015; Grant et al. 2013; Rollof & Fonner 2010). These inconsistent findings point to the need for further investigation of the perceived impact of teleworking on well-being and other perceived effects (Kaluza and van Dick 2023). In addition, because these studies have relied on ad-hoc measures until now, rather than validated ones (see an exception Charalampous et al. 2022), it was important to develop and validate a short measure that could be used to assess how individuals perceive and experience telework in order to understand its effects on work and personal-related outcomes.

This research includes four studies conducted between 2021 and 2022 to develop and validate a new scale that assesses the teleworking experience from the worker’s perspective. We followed the best practices for scale development (e.g., McCoach et al. 2013; Worthington and Whittaker 2006; Zickar 2020). Hence, based on the suggestions multiple samples to describe the development and validation of the TAS were adopted to assessing the extent to which individuals perceive benefits while teleworking.

The first study aimed to develop and construct the items for the scale. Based on McCoach and colleagues’ (2013) suggestions, three methods were used to construct (literature review), define (interviews) and refine the items (survey application). Further, as proposed by Kooken and colleagues (2016), in this first study, two samples were used to develop items and refine the measure to a short and practical scale. Following best practices (see McCoach et al. 2013; Worthington and Whittaker 2006; Zickar 2020) in scale validation procedures, an additional three studies were conducted resorting to multiple samples of teleworkers. In study 2, we relied on a large sample of teleworkers to test the factorial structure of the scale and its reliability (Ahorsu et al., 2022). Finally, in studies 3 and 4, we assessed the convergent, discriminant, and criterion-related validity of the scale to demonstrate its psychometric properties.

3 Study 1: scale development (a qualitative approach)

The first study aimed to develop the items for the scale using three complementary methods: literature review, interviews, and survey application.

3.1 Item generation

The item generation was based on McCoach and colleagues’ suggestions (2013) and occurred in two complementary stages that included the literature review in the first stage and the conduction of interviews in the second stage.

First stage

The TAS was developed in two stages (McCoach et al. 2013; Tortez & Mills, 2022). First, an extensive literature review was performed to analyze studies that were focused on the benefits of telework from the workers’ perspective (e.g., Charalampous et al. 2022; Grant et al. 2019; Junça-Silva et al. 2022b). At this stage, ten outcomes were identified as being associated with teleworking from the worker’s perspective (summarized in Table 1).

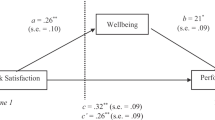

Second stage: The second stage involved 22 interviews with teleworkers (12 women, and 10 men, mean age: 42.21 years old; mean tenure: 18.79 years). These interviews aimed to understand the main benefits of teleworking from the teleworker’s perspective. The content analyses generated nine dimensions of benefits (see Fig. 1): (1) more positive affect (e.g., “I feel joy and happiness while teleworking”) and (2) higher well-being and satisfaction (e.g., “I really appreciate working from home, and feel better because of that”), (3) focus (e.g., “I can easily concentrate on my tasks”), (4) time and stress management (e.g., “As I do not have to commute it spares me a lot of time and stress”), (5) fewer interruptions (e.g., “Teleworking is better because there are many more interruptions at the office”), (6) lessens anxiety (e.g., “working from home allows me to be less anxious even when my day is demanding”), (7) improve performance (e.g., “I can concentrate more on what I have to do, while I am working from home, and I feel I am more productive”), (8) planning and organization of the day (e.g., “I can plan my day differently and I can better manage my time and tasks accordingly”), and (9) work-non work balance (e.g., “On days I work from home, I have more time for my family or other activities, that I cannot have on days I work at the office”).

3.2 Item refinement

Based on the ten dimensions identified in the literature review and the nine categorized in the qualitative analysis of the interviews (see Table 2), two independent researchers identified 16 items related to the benefits of teleworking. They grouped the items into one category of benefits. Subsequently, a third investigator read the items and suggested removing four items with similar content or expression. After removing those items, 12 items were retained for further evaluation.

Second, a panel of experts in telework (comprised of two psychologists, a manager, a human resources manager, and a coach) evaluated the 12 items. They revised the items and provided feedback regarding their clarity, wording, face validity, and redundancy. As a result, two items were excluded based on the panel of experts’ suggestion, leaving 10 items. Thirdly, the 10 retained items were sent to a different panel of experts – familiar with the telework practice (comprised of two experts in human resources and management, an organizational psychologist, one manager, and a labor sociologist) for review. This panel recommended maintaining the 10 items.

After that, this last panel also rated each item for clarity and relevance with each item being rated on a recommended four-point scale (Davis, 1992) – (1 = not relevant, 4 = highly relevant; 1 = not clear, 4 = very clear). Acceptable results can be obtained with a minimum of three experts (Lynn, 1986). Results were interpreted using a content validity index calculated at the item level (I-CVI) to yield an average assessment of an item’s content adequacy (Lawshe, 1975). Results were dichotomized for relevancy (relevant/irrelevant) and clarity (clear/unclear). The I-CVI represents the number of experts rating the item as relevant, or clear (i.e., agreement), divided by the number of experts (Polit & Beck, 2006). All 10 items had an I-CVI > 0.88, hence all of them were maintained (e.g., Lynn, 1986).

3.3 Item relevance and clarity

The final 10-item scale was tested on 80 teleworkers (32 men and 48 women, mean age of 35.33 years and tenure = 9.21 years) to obtain an initial assessment. A five-point Likert scale was used to test whether participants understood the items (1-not at all understandable; 5-completely understood). The results showed that all respondents understood it (M = 4.62, SD = 0.51). In addition, an individual cognitive telephone interview was conducted with the same participants in the pilot study to explore their thoughts about each item on the scale and their responses. Participants indicated that no additional changes were required. Overall, the final version of the scale comprised 10 items that assess the benefits of teleworking from the worker’s perspective.

The second study aims to validate the reliability of the scale, as well as its factorial structure.

4 Study 2: validation of the factorial structure of the TAS

Following the best practices procedure, the aim of study 2 was to evaluate the factorial structure of the TAS, and its reliability on a sample of teleworkers (Tortez & Mills, 2022; Worthington and Whittaker 2006). By doing so, results may then be generalized across populations, even though we do not rely on a representative sample.

4.1 Method

Participants

We collected data from a sample of 602 teleworkers that covered several professional occupations in education (32%), services (30%), financial (25%), and management areas (13%). Of the total sample, 61.6% were female, 46% had a degree, and 38.6% had high school diplomas. They had a mean age of 36.83 years old (SD = 12.15) and a mean organizational tenure of 15.87 years (SD = 12.42). On average, they worked 37.89 h per week (SD = 11.50).

Exclusion/inclusion criteria

We had one major criterion for the inclusion/exclusion of participants. They had to be teleworking, either in a hybrid model or in a full model as the specific amount of time they spent teleworking was not a criterion.

Procedure

We collected data on the TAS online, between March and April 2021. The survey link was sent by email to teleworkers from the researchers’ professional networks. The email also included informed consent for participants to agree to, and the confidentiality and anonymity of the data were also assured on that email. They were also told that they could withdraw from the study at any time. After answering the survey, they were asked to send the link to other contacts, using a snowball procedure. Ethical approval was obtained from the University’s Ethics Committee before conducting the study.

Measures

We collected socio-demographic information regarding gender, age, tenure, education, and hours worked per week.

The Tele Attitude Scale included the 10 items identified in Study 1 (see Table 3). We asked participants to indicate whether teleworking had a positive or negative effect when compared to face-to-face work in each aspect. They rated the items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = much worse, 5 = much better) (α = 0.90).

Data analyses

First, an exploratory factor analysis was performed in SPSS (version 28), and then a confirmatory factor analysis using JASP (Love et al. 2019). The factor structure was evaluated based on common indices and their cut-off points, in which an adequate and model fit Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) should score above 0.90 and 0.95, respectively (Hu and Bentler 1999). In addition, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be below 0.10, 0.08, or 0.05 in order to achieve an acceptable, adequate, and good fit of the model, respectively (Hu and Bentler 1999; Kline 2015). At last, the internal consistency reliability of the TAS was also estimated.

4.2 Results

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the 10 items of the TAS.

4.3 Exploratory Factor Analysis

We followed the recommendations of Hayton et al. (2004) and performed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using parallel analysis in order to determine the appropriate number of factors to extract. Results from the EFA showed that there was only one factor to extract; however, as this method only identifies the number of factors that should be extracted, we performed an additional EFA using maximum likelihood estimation with varimax rotation. This factor explained 53% of the variance.

We analyzed the items’ loadings to search for those which were < 0.45. As all the loadings ranged between 0.50 and 0.74, we did not eliminate any item on the scale (see Table 3). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.88, which indicated that the data was appropriate for the analysis (Kaiser, 1974). Moreover, the reliability analysis supported the internal consistency for the overall scale (α = 0.90).

4.4 Confirmatory factor analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed and supported the unifatorial solution of the TAS. The resulting model fit the data well; χ2(35) = 282.676, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.05; RMSEA = 0.08. The standardized factor loadings were all statistically significant with a p < 0.01 and ranged from 0.53 to 0.86 (Fig. 2).

The results evidenced a good fit solution for the unifactorial structure. Moreover, the scale also presents evidence for internal consistency. The next study assesses the convergent and discriminant validity of the scale.

5 Study 3: convergent and discriminant validity of the TAS

To assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the 10-item scale, we conducted an analysis using an independent sample of teleworkers (e.g., Worthington and Whittaker 2006), to provide more reliable evidence for generalizability that goes beyond the populations from which the studies draw their conclusions.

The convergent validity of the TAS was examined by exploring its relationship with a measure of the quality of telework life. It is likely that teleworkers, while teleworking, feel better and happier. Hence, the TAS should be positively related to the quality of telework life.

Finally, as evidence of discriminant validity, the TAS should evidence no significant association with age, sex, or organizational tenure.

5.1 Method

Participants and procedure

We collected data from 232 teleworkers, of which 58% were female. Most of them were full-time teleworkers (59.1%) and the others had a hybrid teleworking model (40.9%). The mean age was 33.60 years old (SD = 9.40), and the mean organizational tenure was 4.80 years (SD = 6.82). On average, the participants reported working 42 h per week (SD = 9.40). The majority had a degree (80.2%) and 38.4% had a supervisory role.

To gather the data, we placed an announcement on social media (Facebook and LinkedIn) asking teleworkers to participate in a study about attitudes toward telework. It had a hyperlink to the questionnaire. Before answering, they had to agree with the informed consent, which also described the anonymous and confidential nature of the data collection. It was also highlighted that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Data were collected between April and June of 2021.

5.2 Measures

Tele attitude scale

We applied the scale used in study 1 (α = 0.90).

E-Work Life Scale

We used the 17-item-e-work-life scale to measure the individuals’ quality of life while teleworking (Grant et al. 2019). It assesses four dimensions of teleworking, namely work-life interference (seven items; e.g., “Having flexible hours when e-working allows me to integrate my work and non-work life.”), flexibility (three items; e.g., “My supervisor gives me total control over when and how I get my work completed when e-working”), organizational trust (three items; e.g., “My organization provides training in e-working skills and behaviors”), and productivity (four items; e.g., “E-working makes me more effective to deliver against my key objectives and deliverables”). Participants rated it on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) (0.74 > α < 0.81).

Satisfaction with telework

We used two items to measure how satisfied the participants were on teleworking days (e.g., “While teleworking you feel…”; “Teleworking leaves you…”) answered on a 5-point Likert Scale (1-nothing satisfied; 5-completely satisfied) (α = 0.79).

5.3 Results

Table 4 shows the pattern of relationships found. Reliability analysis showed a good internal consistency for the scale (α = 0.90). A confirmatory factor analysis also supported the one-factor solution, as the resulting model fit the data well (χ2(9) = 33.488, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.05).

As expected, the TAS showed positive and significant associations with both the four dimensions of the e-work life scale and the levels of satisfaction while teleworking, which supported the convergent validity of the scale. Moreover, it was not significantly related to age, sex, or tenure. This gave support for the discriminant validity of the scale. The following study tests the criterion validity of the scale.

6 Study 4: an examination of the criterion-validity of the TAS

This study aimed to test the criterion validity of the new scale with a new sample of teleworkers. Research has shown that teleworking leads to positive outcomes for the individual (e.g., improved health, and affect) and organizations (e.g., performance) (e.g., Charalampous et al. 2022; Grant et al. 2019); hence, the TAS should be positively related to performance, health, and positive affect, and negatively related to negative affect, thereby evidencing criterion-related validity.

6.1 Method

Participants and procedure

In this study, 837 teleworkers participated, 52.4% of which were female, with a mean age of 34.08 years old (SD = 7.20), and a mean organizational tenure of 12.21 years (SD = 7.23). Participants reported working about 42.22 h per week (SD = 11.01).

We followed the same procedure as the third study; we collected data between January to March of 2022.

6.2 Measures

Tele attitude scale

We used the same scale from the previous studies (α = 0.90).

Performance

We measured adaptive (Griffin et al. 2007) and task performance (Koopmans, et al. 2013). To measure adaptive performance, we used three items that asked participants to identify how often, in the past week, they had adapted to change (e.g., “I adapted well to changes in core tasks”). They answered on a 5-point scale (1 = very little, 5 = a great deal) (α = 0.91). To measure task performance, we used seven items from the individual work performance questionnaire (Koopmans et al. 2013) (e.g., “I managed to plan my work so that it was done on time”) (α = 0.69). Participants indicated how often they had such behaviors in the past week at work on a 5-point scale (1 = seldom; 5 = always).

Affect

To measure affect, we used the 16-item Multi Affect Indicator (Warr et al. 2014). We measured the positive affect with eight items (e.g., “joyful”; α = 0.92) and the negative affect with the other eight items (e.g., “dejected”; α = 0.93). Participants rated how often they had experienced such affective states while teleworking in the previous week (1 = never, 5 = always).

Health

We used one item, from the SF-36 Health Survey (Ware et al. 2001), to measure the participants’ perceptions of their general health. We asked participants to indicate how well they rated their health (1-very bad, 5-very good).

6.3 Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

We performed confirmatory factor analysis using JASP which evidenced the one-factor solution found in the previous studies. The model fit proved to be adequate to the data (χ2(8) = 192.835, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.06). Likewise, reliability analysis showed a good internal consistency for the scale (α = 0.90).

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics and the correlations between the variables. As expected, the TAS correlated significantly and positively with measures of general health, performance (adaptive, and task performance), and positive affect, and negatively with negative affect, which evidenced the criterion-validity of the scale.

Overall, the results of this study showed that the scale has outstanding reliability and a consistent one factor-solution across different samples. Moreover, the results also evidence that the scale presents criterion validity as it proves to be closely related to several positive indicators, such as performance, health, and affect.

7 General discussion

Recent research has demonstrated that teleworking leads to several positive outcomes for the individual (e.g., well-being; Anderson et al. 2015; Blahopoulou et al. 2022) and organizations (e.g., performance, e.g., Campo et al. 2021; Charalampous et al. 2022; Martin and MacDonnell 2012). Indeed, since the recent pandemic crisis of COVID-19, teleworking has been increasingly adopted as a strategy to improve workers’ engagement and performance (Lopes et al. 2023). Despite this, there is still a need to develop and validate a short-measure to assess how workers perceive telework because the existing studies have used ad-hoc measures instead of validated scales for this purpose (Junça-Silva 2023). Hence, it is timely and relevant to understand how workers perceive the benefits of this working arrangement.

As such, following best practices in scale development and validation, this research resorts to a multi-method and multi-study to develop a short measure that evaluates the attitudes toward teleworking from the worker’s perspective. The objective of undertaking these four studies was to expand the knowledge about the way teleworkers perceive telework, thereby filling this gap in the literature (Charalampous et al. 2022) and contributing for managerial practice.

7.1 Theoretical implications

First, the TAS presents a consistent one-factor structure to evaluate how teleworkers perceive telework. This factor structure is demonstrated across studies 2, 3, and 4. This consistency suggests that the scale may be applied in different research models (e.g., cross-sectional, diary, or longitudinal designs) and in different occupational sectors (Junça-Silva 2023). Moreover, the evidence of reliability – across the studies - makes the TAS a reliable measure to evaluate the attitudes of workers regarding telework.

Finally, the results show that the scale has convergent, discriminant, and criterion-related validity, as shown by (1) the significant relationships with several indicators and by (2) the non-significant associations with age, sex, and tenure, which in turn shows its applicability across different populations. This result highlights that the TAS may be a suitable indicator of how well workers experience telework regarding different aspects (e.g., productivity).

The associations between the TAS and indicators of performance, health, and affect are in line with recent demonstrations that teleworking enhances the workers’ focus on their tasks, which in turn improves performance (e.g., Liu et al. 2021; Lopes et al. 2023). This is explained, in part, because when individuals work from home, they do not need to commute (Kaluza and van Dick 2023), which saves time and stress from experiencing traffic jams (Šmite et al. 2023), resulting in more time to work (Junça-Silva 2023) and higher levels of concentration on the tasks to be done (e.g., Bailey and Kurland 2002; Junça-Silva et al. 2022b). Indeed, teleworking also appears to benefit the way individuals organize and manage their work autonomously and flexibly (Meier et al. 2023) thus improving their productivity (Charalampous et al. 2022; Grant et al. 2019) and performance (Gohoungodji et al. 2023).

Additionally, on days in which individuals work from home, they can be engaged in other activities, such as those related to the family or their pets (Junça-Silva 2023), which, in turn, may promote work-non-work balance (Campo et al. 2021) and minimize the stress felt with the pressure to balance each life domain (Chambel et al. 2023). Plus, other studies have demonstrated that teleworking benefits workers who own pets as they can spend more time with them and hence be happier (Junça-Silva 2022). In line with this, recent studies have also shown that teleworking with pets nearby improves positive attitudes at work, such as organizational identification (Biron et al. 2023) and work engagement (e.g., Grant et al. 2019), and well-being indicators, such as positive affect (Kaltiainen and Hakanen 2023), job satisfaction (Lu and Zhuang 2023), and perceived health (e.g., Pina-Cunha et al., 2019; Powell et al. 2020). Thus, telework may be perceived more favourably for those who experience higher work-non-work balance and less conflict between each domain (Gualano et al. 2023).

Overall, the TAS appears to be a reliable and valid measure of how teleworkers perceive telework; thus, it may be helpful to increase understanding of this topic. Although it does not assess the telework per se; if an overall telework attitude scale is needed, and a brief scale is desirable (for instance, for daily diary studies), the TAS appears to be adequate. If separate component scores are needed, additional scales should be used, for instance, the e-work life scale developed by Grant and colleagues (2019) and refined by Charalampous and colleagues (2022).

7.2 Practical implications

The TAS can be helpful to expand what is known about attitudes toward teleworking from the employees’ perspective. It is relevant to understand the teleworkers’ perspective regarding the main benefits that this flexible working regimen may have because each individual may experience teleworking in different ways that may be both positive (for instance, when one experiences higher periods of productivity while working from home) and negative (for instance, when one lacks a physical space to be working from home; Kazekami 2022). Understanding individual differences in attitudes toward teleworking is relevant to designing effective organizational strategies that are targeted to adopt or limit telework (Šmite et al. 2023).

As such, from an applied perspective, organizations and managers may benefit from a short measure that diagnoses how their workers perceive and experience teleworking regarding well-being, productivity, work-non-work balance, work-related interactions, and job characteristics. Moreover, this measure is also relevant for managers to analyse how their teleworkers are experiencing teleworking regarding their well-being and productivity. This will help to identify strategies that may improve their work-related well-being while teleworking (for instance, to create counselling or supervisory moments as a strategy to advise on how to cope with negative situations on teleworking) or to reduce the number of days of teleworking for those who experience it negatively.

7.3 Limitations and future research directions

The scale presented here is promising, although more validity studies are needed. The first limitation is related to the sample as we do not have a representative sample of national teleworkers. However, we must consider that we have different studies that rely on different samples which is an added value and thus strengthens these conclusions. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the studies may have led to the common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). However, the findings show that the common method bias is not a severe issue in this study as demonstrated by the results from the confirmatory factor analysis and reliability indices.

Future research should explore further the validity of the TAS. First, it will be important to determine the associations of the scale with nonself-report assessments, for example from familiars (e.g., husband/wife), and also to use the scale to predict nonself-report behaviours (e.g., behaviours from the other parts, including wife/husband or dependents). It will also be desirable to establish the stability of the TAS over time.

Other studies should explore the relations between the TAS and teleworkers’ perceptions regarding relevant organizational outputs, such as performance, through a daily design. Daily designs are particularly important when it is necessary to consider daily fluctuations, as performance levels tend to have (Griffin et al. 2007).

Lastly, future research should analyze the degree to which the new scale and existent scales differ and converge across cultures and groups.

8 Conclusion

The increasing popularity of telework – due to the recent pandemic crisis –- makes the TAS proposed in this work a long overdue and sorely needed measure. The lack of such a tool has contributed to the field’s incomplete understanding of how workers perceive teleworking and how they may therefore deal with it. The TAS may satisfy this need because aims to measure the perception of workers regarding telework and evidences good psychometric properties regarding its factorial structure, reliability, and validity (convergent, discriminant, and criterion-related). This measure also intentds to serve as an instrument helpful for academics and practitioners who intend to expand the knowledge about this topic and delineate appropriate solutions for employees and employers.

Data availability

The data is available only upon reasonable request to the authors.

References

Ahorsu, D.K., Lin, C.Y., Imani, V., et al.: The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment Health Addict. 20, 1537–1545 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

Anderson, A.J., Kaplan, S.A., Vega, R.P.: The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 24(6), 882–897 (2015)

Athanasiadou, C., Theriou, G.: Telework: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Heliyon. 7(10), e08165 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08165

Bailey, D.E., Kurland, N.B.: A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J. Organizational Behav. 23(4), 383–400 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1002/job.144

Barber, L.K., Santuzzi, A.M.: Please respond ASAP: Workplace telepressure and employee recovery. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 20(2), 172 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038278

Baruch, Y.: Teleworking: Benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New. Technol. work Employ. 15(1), 34–49 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00063

Baruch, Y.: The status of research on teleworking and an agenda for future research. Int. J. Manage. Reviews. 3(2), 113–129 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2370.00058

Biron, M., Casper, W.J., Raghuram, S.: Crafting telework: A process model of need satisfaction to foster telework outcomes. Personnel Rev. 52(3), 671–686 (2023)

Blahopoulou, J., Ortiz-Bonnin, S., Montañez-Juan, M., Espinosa, T., G., García-Buades, M.E.: Telework satisfaction, wellbeing and performance in the digital era. Lessons learned during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Curr. Psychol. 41(5), 2507–2520 (2022)

Buomprisco, G., Ricci, S., Perri, R., De Sio, S.: Health and telework: New challenges after COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Environ. Public. Health. 5(2), em0073 (2021). https://doi.org/10.21601/ejeph/9705

Campo, A.M.D.V., Avolio, B., Carlier, S.I.: The Relationship between Telework, Job Performance, work–life balance and family supportive Supervisor behaviours in the Context of COVID-19. Global Bus. Rev., 09721509211049918. (2021)

Chambel, M.J., Castanheira, F., Santos, A.: Teleworking in times of COVID-19: The role of family-supportive supervisor behaviors in workers’ work-family management, exhaustion, and work engagement. Int. J. Hum. Resource Manage. 34(15), 2924–2959 (2023)

Charalampous, M., Grant, C.A., Tramontano, C.: Getting the measure of remote e-working: A revision and further validation of the E-work life scale. Empl. Relations: Int. J., (2022). (ahead-of-print).

Cunha, M.P.E., Rego, A., Munro, I.: Dogs in organizations. Hum. Relat. 72(4), 778–800 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718780210

Davis, L.L.: Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Applied. Nursing. Res. 5(4), 194–197 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0897-1897(05)80008-4

De Vries, H., Tummers, L., Bekkers, V.: The benefits of teleworking in the public sector: Reality or rhetoric? Rev. Public. Personnel Adm. 39(4), 570–593 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X18760124

Eurofound and the International Labour Office: Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work, Publications Office of the European Union and the International Labour Office, Luxembourg and Geneva (2017) available at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_544138.pdf (accessed 12 July 202)

Fonner, K.L., Roloff, M.E.: Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. J. Appl. Communication Res. 38(4), 336–361 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2010.513998

Gálvez, A., Tirado, F., Martínez, M.J.: Work–life balance, organizations and social sustainability: Analyzing female telework in Spain. Sustainability. 12(9), 3567 (2020)

Gillies, D.: Agile bodies: A new imperative in neoliberal governance. J. Educ. Policy. 26(2), 207–223 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2010.508177

Gohoungodji, P., N’Dri, A.B., Matos, A.L.B.: What makes telework work? Evidence of success factors across two decades of empirical research: A systematic and critical review. Int. J. Hum. Resource Manage. 34(3), 605–649 (2023)

Grant, C.A., Wallace, L.M., Spurgeon, P.C.: An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker’s job effectiveness, well‐being and work‐life balance. Empl. Relations. 35(5), 527–546 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2012-0059

Grant, C.A., Wallace, L.M., Spurgeon, P.C., Tramontano, C., Charalampous, M.: Construction and initial validation of the E-Work Life Scale to measure remote e-working. Empl. Relations (2018)

Grant, C.A., Wallace, L.M., Spurgeon, P.C., Tramontano, C., Charalampous, M.: Empl. Relations. 41(1), 16–33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2017-0229 Construction and initial validation of the E-Work Life Scale to measure remote e-working

Griffin, M.A., Neal, A., Parker, S.K.: A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 50(2), 327–347 (2007). https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24634438

Gualano, M.R., Santoro, P.E., Borrelli, I., Rossi, M.F., Amantea, C., Daniele, A., Moscato, U.: TElewoRk-RelAted stress (TERRA), psychological and physical strain of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Workplace Health Saf. 71(2), 58–67 (2023)

Hayton, J.C., Allen, D.G., Scarpello, V.: Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Res. Methods. 7(2), 191–205 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428104263675

Hill, E.J., Miller, B.C., Weiner, S.P., Colihan, J.: Influences of the virtual office on aspects of work and work/life balance. Pers. Psychol. 51(3), 667–683 (1998)

Hu, L.T., Bentler, P.M.: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 6(1), 1–55 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Cortese, C.G., Molino, M., Pasca, P., Ciavolino, E.: Development and validation of the remote working benefits & disadvantages scale. Qual. Quant. 1–25 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01364-2

Junça-Silva, A.: Friends with benefits: The positive consequences of Pet-Friendly practices for workers’ well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19(3), 1069 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031069

Junça-Silva, A., Silva, D.: How is the life without unicorns? A within-individual study on the relationship between uncertainty and mental health indicators: The moderating role of neuroticism. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 188, 111462 (2022)

Junça Silva, A., Neves, P., Caetano, A.: Procrastination is not only a thief of time, but also a thief of happiness: It buffers the beneficial effects of telework on well-being via daily micro-events of IT workers. Int. J. Manpow. (2022a)

Junça-Silva, A., Almeida, M., Gomes, C.: The role of dogs in the relationship between Telework and Performance via Affect: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Analysis. Animals. 12(13), 1727 (2022b). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131727

Junça-Silva, A.: The Telework Pet Scale: Development and psychometric properties. J. Veterinary Behav. 63, 55–63 (2023)

Kaltiainen, J., Hakanen, J.J.: Why increase in telework may have affected employee well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic? The role of work and non-work life domains. Curr. Psychol., 1–19. (2023)

Kaluza, A.J., van Dick, R.: Telework at times of a pandemic: The role of voluntariness in the perception of disadvantages of telework. Curr. Psychol. 42(22), 18578–18589 (2023)

Kazekami, S.: Mechanisms to improve labor productivity by performing telework. Telecomm. Policy. 44(2), 101868 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101868

Kazekami, S.: Is Remote Working a Magic Wand? Geographic Differences in the Feasibility of Working from Home and Women’s Employment. Geographic Differences in the Feasibility of Working from Home and Women’s Employment (December 24, 2022). (2022)

Kerrin, M., Hone, K.: Job seekers’ perceptions of teleworking: A cognitive mapping approach. New. Technol. Work Employ. 16(2), 130–143 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00082

Kline, R.B.: Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford (2015)

Kooken, J., Welsh, M.E., McCoach, D.B., Johnston-Wilder, S., Lee, C.: Development and validation of the mathematical resilience scale. Meas. Evaluation Couns. Dev. 49(3), 217–242 (2016)

Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C., Hildebrandt, V., Van Buuren, S., Van der Beek, A.J., De Vet, H.C.: Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. Int. J. Productivity Perform. Manage. 62(1), 6–28 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401311285273

Liu, L., Wan, W., Fan, Q.: How and when telework improves job performance during COVID-19? Job crafting as mediator and performance goal orientation as moderator. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manage. 14, 2181 (2021)

Lopes, S., Dias, P.C., Sabino, A., Cesário, F., Peixoto, R.: Employees’ fit to telework and work well-being:(in) voluntariness in telework as a mediating variable? Empl. Relations: Int. J. 45(1), 257–274 (2023)

Love, J., Selker, R., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Dropmann, D., Verhagen, J., Wagenmakers, E.J.: JASP: Graphical statistical software for common statistical designs. J. Stat. Softw. 88, 1–17 (2019). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v088.i02

Lu, Z., Zhuang, W.: Can teleworking improve workers’ job satisfaction? Exploring the roles of gender and emotional well-being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life, 1–19. (2023)

Lunde, L.K., Fløvik, L., Christensen, J.O., Johannessen, H.A., Finne, L.B., Jørgensen, I.L., Vleeshouwers, J.: The relationship between telework from home and employee health: A systematic review. BMC Public. Health. 22(1), 47–61 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12481-2

Lynn, M.R.: Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing. Res. 35(6), 382–386 (1986).

Martin, B.H., MacDonnell, R.: Is telework effective for organizations? A meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Manage. Res. Rev. (2012)

McCoach, D.B., Gable, R.K., Madura, J.P.: Instrument Development in the Affective Domain, vol. 10, pp. 978–971. Springer, New York, NY (2013)

Meier, M., Maier, C., Thatcher, J.B., Weitzel, T.: Cooking a telework theory with causal recipes: Explaining telework success with ICT, work and family related stress. Inform. Syst. J. (2023)

Morganson, V.J., Major, D.A., Oborn, K.L., Verive, J.M., Heelan, M.P.: Comparing telework locations and traditional work arrangements: Differences in work-life balance support, job satisfaction, and inclusion. J. Managerial Psychol. (2010)

Nilles, J.: Telecommunications and organizational decentralization. IEEE Transactions on Communications. 23(10), 1142–1147 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOM.1975.1092687

Nilles, J.M. Telework: enabling distributed organizations: implications for IT managers. Inf. Syst. Manag. 14(4), 7–14 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1080/10580539708907069

Nilles, J.M.: Strategies for managing the virtual workforce. In: Nilles, J.M., (ed.) Managing telework, pp. 64–100. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Canada (1998).

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.-Y., Podsakoff, N.P.: Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88(5), 879–903 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Polit, D.F., Beck, C.T.: The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nursing. Health. 29(5), 489–497 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20147

Powell, L., Edwards, K.M., Michael, S., McGreevy, P., Bauman, A., Guastella, A.J., Stamatakis, E.: Effects of human–dog interactions on salivary oxytocin concentrations and heart rate variability: A four-condition cross-over trial. Anthrozoös. 33(1), 37–52 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2020.1694310

Šmite, D., Moe, N.B., Klotins, E., Gonzalez-Huerta, J.: From forced Working-from-home to voluntary working-from-anywhere: Two revolutions in telework. J. Syst. Softw. 195, 111509 (2023)

Taskin, L., Bridoux, F. Telework: A challenge to knowledge transfer in organizations. Int. J. Human Resource Manag. 21(13), 2503–2520 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.516600

Tavares, A.I.: Telework and health effects review. Int. J. Healthc. 3(2), 30–36 (2017). https://doi.org/10.5430/ijh.v3n2p30

Tortez, L.M., Mills, M.J.: In good company? Development and validation of the family-supportive coworker behavior scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 136, 103724 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103724

Ware, J.E., Kosinski, M., Keller, S.: SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales. A user’s manual, 1994. (2001)

Warr, P., Bindl, U.K., Parker, S.K., Inceoglu, I.: Four-quadrant investigation of job-related affects and behaviours. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 23(3), 342–363 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.744449

Worthington, R.L., Whittaker, T.A.: Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. Couns. Psychol. 34(6), 806–838 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127

Zickar, M.J.: Measurement development and evaluation. Annual Rev. Organizational Psychol. Organizational Behav. 7, 213–232 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044957

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, grant UIDB/00315/2020.

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance of ethical standard statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Junça-Silva, A., Caetano, A. How good is teleworking? Development and validation of the tele attitude scale. Qual Quant (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01887-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01887-w