Abstract

We introduce a novel approach to operationalizing growth models. Drawing on the most recent release of OECD Input–Output Tables, we compute the import-adjusted growth contributions of consumption, investment, government expenditures, and exports for sixty-six countries in the years 1995–2007 and 2009–2018, covering not only advanced Western economies but also Central and Eastern European, South-East Asian, and Latin American countries. We find that most are export-led or domestic demand-led and other forms of growth are rare. Our results differ from other classifications in that they reveal important geographical variation as well as temporal change. In a subsequent step, we illustrate the utility of the methodology by investigating the link between real exchange rate devaluation and export-led growth, a contentious issue in the existing literature. For pre-crisis advanced Western economies, we find an association between the two variables, which is statistically significant only when our new indicator is used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The past few years have seen a surge of interest in “growth models” among comparative and international political economists and post-Keynesian economists (Baccaro and Pontusson 2016; Behringer and van Treeck 2019; Hassel and Palier 2021). This rapprochement of social scientists and heterodox economists promises to revitalize “political economy” as an interdisciplinary field of study (Stockhammer and Kohler 2022).

Yet, research on growth models is hindered by the lack of consensus on their conception and operationalization. When talking about growth models, some researchers refer to the effects of changes in some ultimate “drivers” of growth (e.g., the factor distribution of income), while others are interested in the actual growth contribution of particular aggregate demand components (e.g., consumption or exports). The approaches used for measuring growth models vary accordingly.

In this paper, we present a new methodology for operationalizing growth models, which applies growth decomposition to “import-adjusted” demand components (Auboin and Borino 2018; Bussière et al. 2013). This methodology identifies the key demand contributors to growth for specific countries in given periods, thus providing an objective basis for the distinction between not only consumption- and export-led growth models, on which the discussion has mostly focused so far, but also investment- and government expenditure-led ones, or some combination thereof.

The main advantage of the import-adjusted demand component approach is that it accounts for different types of import expenditures for consumption, investment, government spending, and export purposes. Growth decomposition focusing on net exports, that is, subtracting all imports from exports as it is usually done, understates the growth contribution of exports and overstates that of domestic demand, especially consumption. Furthermore, growth decomposition is a purely descriptive exercise, which does not require acceptance of the validity of any particular economic model. The resulting data can be used to investigate the “drivers” of different types of growth (e.g., shifts in wage/profit shares, changes in the personal distribution of income, changes in household debt, trends in asset prices, price and non-price competitiveness of exports, etc.).

The methodology developed in this paper requires input–output tables (IOTs) to calculate import-adjusted demand components. Until not long ago, IOTs were only available for a limited number of countries and years. Furthermore, they were based on different statistical standards for different periods, and thus not directly comparable. However, the OECD’s most recent release of IOTs includes standardized data for sixty-six countries between 1995 and 2018. We use these data (7,069,392 observations in total) to construct measures of growth models for all countries in the OECD IOT database for two periods: the pre-financial crisis period (1995–2007) and the post-crisis period (2009–2018).

Our results suggest that most countries are export-led or domestic demand-led (where domestic demand is the sum of consumption, investment, and government spending). Consumption-led economies are rare, and the US is the only advanced country to consistently fall into this category. Most continental European countries are export-led, while the "liberal market economies" are domestic demand-led. The Nordic countries deserve a category of their own, since household consumption, investment, and government expenditures are more important for their growth profiles and exports less important than for continental countries. The analysis also uncovers change over time. Both the Mediterranean and the Central and Eastern European countries (CEE) responded to the crisis by moving clearly towards export-led growth, while the South-Eastern Asian and Latin American countries had more differentiated responses, but overall moved in the opposite direction.

In a second step, we illustrate how the newly created indicators can be used to explore substantive questions about the determinants of different types of growth. In particular, we explore a question that has received conflicting answers in the literature on growth models: is export-led growth dependent on real exchange devaluation as argued by Baccaro and Pontusson (2016), or is it better explained by the quality of exports as Kohler and Stockhammer (2021), Hein et al. (2021), and others maintain?

We do not find a generalized relationship between export-led growth and real exchange rate devaluation across all time periods and country groups. However, real exchange rate devaluation is strongly associated with export-led growth in advanced Western countries in the pre-crisis period, while export complexity is not. Importantly, this relationship is only statistically significant when the import-adjusted measure of export-led growth is used, but not if the indicator is based on net exports.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: the next section reviews the existing literature on growth model operationalization. We then introduce our methodology before presenting our growth model indicators for sixty-six countries divided into fourteen regional groups and two time periods. This is followed by an analysis of the trade-off between export-led and consumption-led growth and of the determinants of export-led growth. The concluding section discusses avenues for empirical research using the data presented in the paper.

2 The literature on growth model classification and operationalization

The empirical research on growth models is rapidly expanding and now covers a growing number of topics: cross-country variation in growth trajectories (Baccaro and Pontusson 2016; Bohle and Regan 2021; Johnston and Regan 2018); changes in growth trajectories over time (Erixon and Pontusson 2022; Höpner 2019; Reisenbichler and Wiedemann 2022); variation in policy stance across countries (e.g., fiscal policy, tax policy) as a result of growth model differences (Haffert and Mertens 2021; Hopkin 2020; Hübscher and Sattler 2022); the impact of growth models on individual preferences (Baccaro and Neimanns 2022; Hübscher et al. 2022); the effects of cross-country institutional differences on patterns of inequality and growth (Behringer and van Treeck 2019); the impact of particular sectors on growth (Bürgisser and Di Carlo 2022); and the relationship between growth models and central bank policies (Reisenbichler 2020).

Despite the growing popularity of the notion of growth models and its deployment as dependent and independent variable in a number of empirical analyses, there is no consensus on the definition of growth models and no generally accepted methodology for operationalizing them. Different authors use the label to designate slightly different objects. It is therefore important to provide some conceptual and methodological clarification.

Baccaro and Pontusson (2016) have used growth decomposition between consumption, investment, government expenditures, and net exports to operationalize growth models. Thus, Germany was classified as an export-led growth model because net exports provided the largest contribution to German growth between 1994 and 2007; the UK as a consumption-led growth model for analogous reasons; Sweden as a balanced growth model for its ability to combine export-led and consumption-led growth contributions; and Italy as a case of stagnation due to the lack of any sufficiently dynamic demand component. Growth decomposition was then coupled with a (rudimentary) analysis of the determinants of different types of growth, focusing in particular on wage growth, household debt, and the price sensitivity of exports. Recently, Mertens et al. (2022) have used the growth decomposition approach to classify the growth models of nine emerging market economies.

Cardenas and Arribas (2021, Chapter 1) also use growth decomposition to identify growth models, coupling it with an analysis of the relationship between consumption and investment, respectively, and the net export share of GDP. Furthermore, they engage in an analysis of trajectories of institutional change for a number of European countries in the style of the regulation school approach (Boyer and Saillard 2005). They thus derive three growth models: (1) debt-financed consumption-led (associated with private-sector debt and a current account deficit); (2) export-led; and (3) domestic demand-led.

Hassel and Palier (2021) rely on multiple qualitative and quantitative criteria for identifying growth models. On the one hand, they use the share of a particular demand component (exports or consumption) in GDP to differentiate between export-led and domestic demand-led growth. On the other, they examine variation in countries’ capacity to produce and export high value-added services, which they consider a consequence of their ability to effectively adopt information and communications technology. In conducting this analysis, they examine welfare state institutions and reform policies, as they see them as important facilitators of the transition towards a high value-added service economy. The combination of these criteria leads to five types of growth models: (1) export-led with dynamic services (e.g., Sweden); (2) export-led with manufacturing exports (e.g., Germany); (3) FDI-driven export-led (where exports depend on the ability of the country to attract foreign capital) (e.g., Ireland); (4) domestic demand-led, supported by finance and high value-added services (e.g., the UK); (5) domestic demand-led, with public expenditures as the key growth driver (e.g., Mediterranean countries).

Picot (2021) focuses on how countries could engineer a demand stimulus, arguing that they essentially have three ways to do so: they can bring their private sector into deficit; they can run a public sector deficit; or they can rely on the rest of the world to go into deficit (which corresponds to a current account surplus for the country in question). It is also possible to combine different demand stimuli. With three sectors (private, public, foreign) and two possible states of the world (deficit or no deficit), there are eight potential combinations, but one of them is impossible (private deficit, public deficit, current account surplus) because if the whole domestic economy is in deficit, the country must borrow from the rest of the world and hence be in external deficit.

Based on this framework, Picot (2021) collects data on twenty-eight OECD countries divided into three periods (1995–2000, 2001–2007, and 2010–2016), and then analyzes them using the methodology of fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (Ragin 2000), identifying seven types of growth models: (1) finance-based (aggregate demand stimulation is achieved through private deficit); (2) export-led (a sustained current account surplus stimulates growth); (3) state-led (based on large public deficits); (4) domestic demand-led (based on the combination of private and public deficits); (5) private- and export-led (based on the combination of private deficits and current account surpluses but with public surpluses); (6) state- and export-led (based on the combination of public deficits and current account surpluses but with private surpluses); and (7) balanced (no private or public deficit, no current account deficit). The author finds that export-led growth is dominant in continental European and Nordic countries and finance-led growth is dominant in English-speaking countries, while Mediterranean and CEE countries are more internally diverse.

Picot’s (2021) approach is essentially based on a simplified sectoral balance approach. As such it shares some similarities with that of Hein et al. (2021). These authors use two criteria for identifying growth models: growth decomposition across consumption, investment, government expenditures, and net exports; and the net financial balances of sectors (household, non-financial private firms, financial private firms, public sector, and foreign sector). The latter criterion is used to shed light on the manner in which demand is financed. They thus infer four types of growth models, as follows: (1) Export-led mercantilist is characterized by a large growth contribution of net exports, while the growth contribution of domestic demand is small or negative. (2) Weakly export-led has a similar configuration to the previous type, but the growth contribution of export surpluses is lower. The Mediterranean countries after the euro crisis are classified as weakly export-led, too. (3) Domestic demand-led is characterized by a government sector in deficit and a private sector in financial surplus, while the current account is in balance or moderate deficit. (4) Debt-led private demand boom has the private sector as a whole in deficit, including the household sector, and sees endemic current account deficits.

Hein et al. (2021) also clarify the distinction between the concept of “demand regime” as used by post-Keynesian and regulationist economists (e.g., Boyer 1988) and that of “growth models” as used by comparative political economists. A demand regime is a counterfactual entity, which depends on an underlying structural model of the economy – for example, neo-Kaleckian (Bhaduri and Marglin 1990) or neo-Sraffian (Girardi and Pariboni 2016). This model defines the ultimate determinants of growth: for example, propensity to consume, sensitivity of investments to profits and aggregate demand, price sensitivity of exports and imports, demand sensitivity of imports and exports, autonomous (debt-financed) consumption. To identify a “demand regime,” it is necessary to examine what would happen to aggregate demand if, for example, the functional distribution of income between wages and profits were to change at the margin in favor of wages. If demand expands, the demand regime is wage-led; vice versa, it is profit-led. Capital accumulation can also be wage-led or profit-led depending on whether investments are more responsive to the expansion of demand or to the profit share. Labor productivity, too, is affected by shifts in the functional distribution of income and can be wage-led or profit-led (Storm and Naastepad 2012).

A country having a wage-led or profit-led demand regime is not the same as actual growth being caused by an increase in the wage share or profit share. Actual growth is determined by the combination of the structural features of an economy, which shape the demand regime, and the policies enacted in the country, which could be pro-labor or pro-capital (Lavoie and Stockhammer 2013). If there is congruence between the demand regime and the policy regime (for example if pro-labor policies are implemented in a wage-led demand regime), growth will ensue; if there is a mismatch (for example if pro-capital policies are implemented in a wage-led demand regime), there will be stagnation.

Building on the distinction between structural determinants of growth and actual growth, Kohler and Stockhammer (2021) critique the use of growth decomposition for classifying growth models. Looking at the growth contributions of consumption, investment, government expenditures, and net exports, they argue, says little about the ultimate sources of growth. For example, consumption-led growth may be driven by an increase in the bargaining power of workers, or by an increase in households’ access to debt, or by the impact of appreciating house prices, or by some combination of these factors. In addition, they argue that growth accounting per se may lead to misclassification of a country’s growth process. For example, after the sovereign debt crisis, the Mediterranean countries were forced to drastically reduce the volume of imports without exports increasing much. The application of a growth accounting methodology would lead to these countries being classified as examples of export-led growth, but in reality the increase in the growth contribution of net exports is due to the drastic contraction of imports. Furthermore, in financialized capitalism, growth is subject to endogenous cycles (Minsky 1992). Countries relying on debt-led growth first experience a period of boom, which is followed by a bust period when the private sector starts to deleverage. If a growth decomposition approach is used, these different phases of the same cycle will appear as shifts in the growth model unless the time frame is sufficiently long.

As a result, Kohler and Stockhammer (2021) recommend analyzing the role of growth drivers through econometric analyses in which the dependent variable is either GDP or some specific components of it (e.g., consumption, investment, exports, imports) and the independent variables are selected based on a model of the structural determinants of growth. The ultimate drivers of growth are shifts in wage or profit shares as underscored by neo-Kaleckian models, as well as shifts in the distribution of personal income, changes in household debt, and asset prices. Econometric analysis reveals that shifts in factor income play a limited role when compared with the role played by household debt and house price movements (Stockhammer and Wildauer 2016).

In brief, an analysis of the existing literature reveals a lack of consensus on the number and type of growth models and on the most appropriate approach for operationalizing them. Most authors adopt some form of growth decomposition, but others recommend against its use. In our view, growth decomposition has several advantages, as it is a purely descriptive exercise, which does not require acceptance of the validity of any particular model of the economy. By contrast, estimating the ultimate drivers of growth requires acceptance of a particular model as correct. Neo-Kaleckians underscore movements in factor shares (wage or profit shares), and neo-Sraffians the autonomous demand components, as the ultimate drivers (Girardi and Pariboni 2020). Relatedly, the estimation of the effects of growth drivers relies on often questionable assumptions about the exogeneity of variables. Furthermore, differences in specification, time period of the analysis, and estimation approach often produce different estimates (Blecker 2016). Growth decomposition is instead model-free and assumption-free. In addition, the required data series are generally available for numerous countries and for long periods. However, growth decomposition needs to be adjusted to correct a problem of interpretation, which we discuss in the next section.

3 Problems with traditional growth decomposition

The methodology of growth decomposition is simple and straightforward. Starting from the expenditure-based representation of GDP (Y) as the sum of consumption (C), investments (I), government expenditures (G), and exports minus imports (X – M), the growth contribution of each demand component K is equal to the percentage change of the demand component times the share of the demand component in GDP at time zero:

However, by subtracting imports entirely from exports, this method of growth decomposition leads to an underestimation of the economic importance of exports and an overestimation of the importance of the domestic demand components (especially consumption). Exports only absorb a portion of imports. The vast majority of imports are consumed. Some imports are also used as investment goods or purchased by governments and should thus be deducted from consumption, investment, and government expenditures, respectively.

Consider the extreme example of an economy that produces solely for export, has no investment and no government expenditures (but the argument would not change if they were included), and uses the export revenues to pay for imports, which are then consumed. By design, this is an export-led economy with a balanced trade account. Let us assume that all components of aggregate demand equal 100 at time zero:

Let us now increase all demand components by 10%:

If we conduct growth decomposition according to the formula described in Eq. (2), we find that the economy has grown by 10% and all growth is consumption-led, while the growth contribution of (net) exports is zero, which is patently false in substantive terms.

Let us now distinguish between imports that are absorbed by consumption (\(M_{C}\)) and imports that are absorbed by exports \((M_{X} )\) (such as raw materials or intermediate products used in the production of exports), which in this particular case are assumed to be zero. For all demand components, and not just for exports, we calculate their net values:

If we assume again that all demand components grow by 10% and we apply the growth decomposition formula, we find that all growth is export-led and the growth contribution of consumption is nil, which is correct both arithmetically and substantively.

This example shows that traditional growth decomposition may lead to misclassification. While subtracting imports solely and entirely from exports makes sense if one is interested in the net financial balance of a country vis-à-vis the rest of the world (net trade and current account balance), it leads to an underestimation of the growth contribution of exports and an overestimation of that of domestic demand. In order to obtain the correct answers from growth decomposition, import-adjusted demand components are required. However, national accounts data do not distinguish between the portion of imports that is absorbed by each demand component and only provide the total value of imports. In order to calculate import-adjusted demand components, it is necessary to use input–output tables and apply the methodology we lay out in the next section.

4 Methodology for deriving import-adjusted demand components

Our goal is to reformulate the expenditure-based formula for GDP (Y) as the sum of net (import-adjusted) demand components. For this, we need to decompose imports (M) into the import expenditures absorbed by each demand component:

The four terms in brackets represent the import-adjusted contribution to aggregate demand of consumption, government spending, investment, and exports, respectively.

Input–output tables provide the information needed to derive the import-adjusted demand components. A stylized representation of an IOT is reported in Table 1.

The economy is composed of n sectors. The rows of the IOT record the output of each sector i as the sum of the sales of intermediate outputs to the j domestic sectors of the economy (matrix Zd) plus final demand (matrix Fd)—consumption, investment, government expenditures, and exports. The columns of the IOT report the inputs used by each sector j to produce its output as the sum of intermediate inputs purchased from the i domestic sectors of the economy plus foreign imports of intermediate inputs (matrix Zm) purchased by sector j from sector i plus value added (Miller and Blair 2009, Chapter 2). Notice that the IOT also reports, sector by sector, the direct imports of goods and services that satisfy each component of final demand (matrix Fm). This information is not available in standard national accounts data. For each sector i and each final demand component k, the total value of the sectoral output x is:

where \(z_{i,j}^{d}\) is the output sold by sector i to sector j and \(f_{i,k}^{d}\) is one of k final demand components satisfied by the output of i.

Data on direct imports are not sufficient on their own to calculate import-adjusted demand components. In addition, we need to calculate indirect imports, that is, the value of imports “induced” by spending on goods and services produced domestically. Imports of intermediate inputs from foreign suppliers, as well as imports incorporated in intermediate inputs bought from domestic suppliers, fall into this category. In order to estimate indirect imports, we follow the methodology of Bussière et al. (see also Auboin and Borino 2018; Bussière et al. 2013). The step-by-step procedure is described in Appendix A and allows the derivation of the Mind matrix, which indicates, sector by sector, the indirect imports associated with each component of final demand.

Since imports are the sum of direct and indirect (induced) imports, and direct imports are given by Fm, total imports \(M^{tot}\) are equal to:

The total final expenditures linked to each demand component are given by the sum of final expenditures on domestically produced goods and services (Fd) and on directly imported goods and services (Fm):

We can now calculate the import-adjusted final demand components:

The formula above shows clearly that the import-adjusted demand components are expenditures on domestically produced goods and services minus the expenditures on imports that are indirectly induced by domestically produced goods and services.

Having derived the import-adjusted values, we apply the growth contribution formula [Eq. (2)] to obtain the import-adjusted growth contributions of consumption, investment, government expenditures, and exports.

Appendix A provides more details about the methodology. Before presenting the import-adjusted demand contributions to growth for several countries, the next section discusses the data.

5 The OECD Input–Output Tables

We use the latest release of the OECD Input–Output Tables (IOTs) database, which covers sixty-six countriesFootnote 1 for all years between 1995 and 2018. These countries on average account for 87.9% of world GDP in 1995–2018. While other sources of IO tables exist, most notably a series of standardized IO tables made available by the World Input–Output Database (WIOD) for forty-three countries between 2000 and 2014 (Dietzenbacher et al. 2013), the latest release of OECD data offers several advantages: it has the largest coverage of countries (66) and sectors (45); it uses the same statistical classification for all years (ISIC Rev 4), differently from the previous release of OECD IOTs, which followed ISIC Rev 3 (34 sectors) between 1995 and 2011 and ISIC Rev 4 (36 sectors) between 2005 and 2015. Using standardized data makes it possible to construct a single time series between 1995 and 2018 without gaps. Importantly, the latest OECD IOT release seems to have a higher quality of data than both the WIOD and previous releases of the OECD IOTs, particularly with regard to direct re-exports, which lead to very high values of import-adjusted contributions of exports for some countries (such as the Netherlands and Belgium) when other datasets are used.Footnote 2

The validity of the OECD IOT data for any particular country depends on gross domestic product (GDP) being a valid measure of economic activity in that country. This assumption is, however, dubious for countries that are legal hosts to a large number of multinational companies (Ergen et al. 2022; Linsi and Mügge 2019). For such countries, gross national income (GNI) is generally preferable to GDP, because it excludes the net income sent to or received from abroad, and hence the repatriated profits of foreign multinationals.Footnote 3 However, we are unable to calculate the GNI from the IOT data. To obviate this problem, we have compared the growth of GDP (calculated from our data) with the growth of GNI (from the World Bank World Development Indicators database). We find that the growth of GDP is on average considerably higher than the growth of GNI for four countries: Luxembourg (1.08%), Ireland (0.92%), Singapore (0.54%), and Malta (0.51%). Therefore, although we calculate demand contributions to growth for these countries as well, we exclude them from the statistical analyses that follow.

6 Demand contributions to growth

We can now compute the average annual growth rate of GDP for each country and the average relative import-adjusted growth contribution of four demand components—consumption, investment, government expenditures, and exports—for two periods: 1995 to 2007, and 2009 to 2018. All values are at basic prices, that is, before taxes less subsidies on final products.

For presentation purposes, we group the sixty-six countries in the OECD IOT database into the following categories: (1) continental European countries (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Switzerland); (2) liberal market economies (Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, UK, and US); (3) Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden); (4) Mediterranean/mixed countries (Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, and Spain); (5) Central and Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia); (6) Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania); (7) advanced Asian countries (Japan and South Korea); (8) other countries of the Western bloc (Israel and Turkey); 9) South-East Asian countries (Cambodia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Taipei, Thailand, and Vietnam); (10) China; (11) India; (12) African countries (Morocco, South Africa, and Tunisia); (13) Central and Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Peru); (14) natural resource-rich countries, defined as those that have rents derived from natural resources (variable available in the World Bank World Development Indicators database) whose average value is higher than 10% of GDP between 1995 and 2018, which are Saudi Arabia (37.56%), Brunei (23.68%), Kazakhstan (19.39%), and Russia (14.20%).

A few clarifications about these country groupings are in order. We start from the varieties of capitalism (VoC) distinction between coordinated and liberal market economies (Hall and Soskice 2001). In the former, a logic of strategic coordination among actors prevails; in the latter, market coordination prevails. We then distinguish between continental European and Nordic countries; VoC regards them all as coordinated market economies (CME), while other researchers (e.g., Pontusson 2005) place them in a separate group. The Mediterranean/mixed economies category is also drawn from VoC. In these countries, the state traditionally plays a key role in economic coordination (Ferrera 1996; Schmidt 2002). The other country groups are based on geographical proximity, population size (China and India), or high rents derived from natural resources.

We associate a country’s growth model with the demand component that provides the largest growth contribution in a given period. Specifically, we use the following criteria to classify growth models:

-

(1)

If the growth contribution of a demand component is greater than 40%, the growth model is “led” by that component. With this rule, there can in principle be two leading demand components simultaneously, but this is rare.

-

(2)

If the growth contribution of a demand component is greater than 50%, the growth model is strongly reliant on that component.

-

(3)

If any two demand components jointly account for 70% or more of growth, the growth model is led by a combination of the two components.

-

(4)

If the three domestic demand components (consumption, investment, and government expenditures) account jointly for at least 70% of growth, the growth model is domestic demand-led.

-

(5)

If the growth contribution of exports is between 30 and 40% (i.e., the contribution of domestic demand is less than 70%), the growth model is balanced.

These thresholds are virtually the same as the ones one would select on purely empirical grounds if one focused on the distribution of growth contributions from domestic demand and exports (in particular, the median and the 33% and 66% percentiles). Appendix D provides details on the empirical validation of the thresholds.

Since growth patterns can be erratic in the short term, we compute GDP growth over two long periods. These are 1995 to 2007 (the period before the financial crisis), and 2009 (the first year after which GDP starts growing again for all countries after the financial crisis) to 2018 (the last available year). Table 2 reports the calculations, distinguishing between the pre- and the post-financial crisis period. For reasons of space, we do not comment on all findings, especially in the case of emerging countries for which we lack sufficient substantive knowledge. We also plot the changes in growth models over time distinguishing between the contributions to growth of domestic demand and exports (Fig. 1). On the axis we have the relative contribution of exports in the two periods (and implicitly also that of domestic demand since it is the complement of this contribution), while on the y-axis we have the list of countries. The size of the two dots identifying the relative contribution of exports in the two periods is proportional to GDP growth in the respective period, while the color of them distinguishes the two periods. The oriented segment joining them represents the change in the relative contribution of exports between the two periods. Negative relative contributions of exports (Argentina and Brunei post-2008) or greater than 100% (Italy, Portugal, Croatia, Cyprus, Spain, Bulgaria post-2008) are outside the extremes considered for the x-axis in order to increase visibility for most country-periods. For Greece, the average growth rate is negative for the post-crisis period. Hence Fig. 1 only reports the value of the pre-crisis average and the direction of change.

Continental European countries tend to be export-led. In the pre-crisis period, they were all export-led with the exception of the Netherlands, which had a balanced growth model. After the crisis, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands became even more export-led, while in Germany and Switzerland the growth contribution of exports declined slightly. Nonetheless, the growth model remained strongly export-led overall.

Domestic demand and consumption play a more important role in the growth process of the LMEs. In particular, the US is strongly consumption-led in both periods. After the crisis, most countries rebalanced a bit their growth models, and the adjustment was especially pronounced in the UK according to our data. Ireland does not fit at all into the LME category, as it is heavily export-led before and after the crisis.

The Nordic countries are more domestically oriented than the continental European countries. In fact, Denmark is the only country to clear the bar for inclusion in the export-led camp. Interestingly, Sweden and (especially) Norway, responded to the crisis by increasing their reliance on domestic demand, while Iceland and Denmark moved in the opposite direction.

The Mediterranean countries were domestic demand-led in the period before the crisis (in particular, government expenditures gave a greater contribution to growth than in other countries, with all of them being above the median and four of them being above the 89% percentile), but they moved, or rather were forced to move, towards export-led growth after the crisis, including France. In reality, however, export-led growth is the outer face of stagnation for these countries: with growth rates close to zero, and with negative growth contribution of the domestic demand components, the small positive contribution of exports stands out in relative terms. With its strong export-orientation in both periods, Malta is an outlier within the group of Mediterranean countries.Footnote 4

The CEE display a similar pattern to the continental European countries: with the exception of Croatia, Poland, and Romania (which had balanced or domestic demand-led growth models), most CEE countries were export-led before the financial crisis, and all countries increased their reliance on foreign demand in the post-crisis period (Ban and Adascalitei 2022). The Baltics deserve a category of their own: they had very high growth rates, balanced or domestic demand-led (with a prominent role for investment), before the crisis, but became strongly export-led economies with much lower growth rates after the crisis. The experience of Croatia, and to a lesser extent Bulgaria and Romania, resembles that of the Mediterranean countries: they experienced a collapse of domestic demand in the second period and the only positive contribution to growth came from exports.

Coming to the two advanced Asian economies, Japan is strongly export-led in both periods, while South Korea combines growth led by internal demand components as well as by exports. When looking at two countries with strong ties to the West, Turkey and Israel, the former is domestic demand-led throughout the observation period, despite the government’s push to replace wage-led growth with export-led growth after 2007 (Apaydin 2022). Instead, Israel engineered a transition to export-led growth before the financial crisis but switched to domestic demand-led growth after 2008 with policies such as increases in the minimum wage in 2010 and 2015 (Krampf 2020).

The South-East Asian countries are internally diverse: some are export-led economies (Cambodia, Singapore, Taipei, Thailand, Vietnam), while others are domestic demand-led (Laos, Myanmar) or even consumption-led (Indonesia, Philippines). The only country that dramatically changed its growth model between the two periods is Malaysia, which moved from export-led to consumption-led. Perhaps surprisingly, China’s growth model is not export-led. Rather, investment is the most dynamic demand contributor. Indeed, investment has for decades been one of the main engines of growth adopted by the Chinese central government, an engine which at the same time serves as the main driver of technological progress and structural change (Riedel et al. 2007). In line with our findings, the focus on investment has increased further since 2009 in response to the global financial crisis. As for the second large country in Asia, India is very clearly domestic demand- and consumption-led, especially in the post-crisis period (Nölke et al. 2022).

Two of the African countries in our dataset (Morocco and Tunisia) appear to be characterized by an unstable growth trajectory with important shifts in their growth models, while South Africa relied heavily on internal consumption in both periods and experienced a decrease in the importance of exports after 2008. In Latin American countries, growth models seem to change dramatically, and this may be due to the high volatility of commodity markets, on which these countries often depend (Sierra 2022). With some countries shifting from export-led to domestic demand-led growth (Argentina, Chile, Peru) and Mexico moving in the opposite direction before and after the crisis, there is no clear pattern in the region. In Brazil and Columbia, growth is heavily reliant on domestic consumption both before and after the financial crisis. All things considered, the development model of Latin American countries seems to rely on domestic demand more than among South-East Asian countries.

Focusing on resource-rich countries, as the biggest oil exporter in the world, Saudi Arabia was strongly export-led before 2008 but rebalanced its growth strategy after 2008 by relying much more on internal domestic demand, in line with long-term objectives of the Saudi government (Nurunnabi 2017). In a similar way, Kazakhstan was strongly export-led before 2008 and became strongly consumption-led after 2008. By contrast, Russia showed a balanced growth model before 2008, with both consumption and exports making important contributions. After 2008, a fall in consumption made export-led growth the dominant pattern, accompanied by a comparatively strong role of investment.

Overall, the methodology of import-adjusted demand components yields results that resonate with existing analyses. The majority of countries are driven by exports or domestic demand. Consumption-led economies are uncommon, yet the United States is clearly one of them in both the pre-crisis and the post-crisis period. Investments and government expenditures are never a primary growth engine as defined above.

There are distinct and long-lasting contrasts between continental European and LME countries. The former are largely export-oriented while the LMEs are centered on the domestic market (see Hope and Soskice 2016). The Nordic have a profile of their own, different from the continental European countries (contrary to Hein et al. 2021; Hope and Soskice 2016; Picot 2021). Household consumption, investment, and government expenditures are more important for their growth profile, which is not surprising given the larger size of their public sector and welfare states and the greater strength of their labor movements. Both the Mediterranean and the CEE countries responded to the crisis by moving decisively towards export-led growth (Bulfone and Tassinari 2021; Perez and Matsaganis 2018), while the South-East Asian and Latin American countries had more differentiated responses.

Comparing the old and new (import-adjusted) measures of growth contributions, it emerges that import-adjusted demand contributions are lower for the domestic demand components, especially consumption, and higher for exports. For example, the yearly growth contribution of import-adjusted consumption is on average, over the entire sample of countries, 0.8% lower than the growth contribution of consumption calculated with unadjusted data (see Table 3). For exports, import adjustment leads to yearly growth contributions 1.4% greater than the net export contributions calculated with the traditional method. The two measures, import-adjusted and non-import-adjusted, are highly correlated for consumption, investment, and government expenditures (between 89 and 99%), and more moderately correlated for exports (51%). This implies that using import-adjusted demand components is unlikely to make a major difference for statistical analyses focusing on the domestic demand components, while it could make a difference for analyses focusing on the growth contribution of exports, as we will verify below.

7 The drivers of export-led growth

In this section we illustrate how the new data can be used to explore the ultimate “drivers” of growth. We examine the determinants of export-led growth, a topic on which there is no consensus in the literature. Baccaro and Pontusson (2016) emphasize the role of real exchange rate devaluation and the price sensitivity of exports for export-led growth. In contrast, Kohler and Stockhammer (2021) argue that the importance of price competitiveness for growth has been exaggerated and that non-price competitiveness, captured by the economic complexity index, is a more important driver of growth. The skepticism about the role of REER is shared by other authors as well (e.g., Gräbner et al. 2020; Hope and Soskice 2016). A test is therefore in order.

We adopt the same style of analysis as Kohler and Stockhammer (2021) and rely on cross-country correlations at two points in time, before and after the financial crisis, using country averages and descriptive bivariate graphs followed by multiple regressions. The analysis focuses on Western countries and CEE countries (including the Baltics) separately, but it excludes three countries for which GDP is not an appropriate measure of economic activity as discussed above (Ireland, Luxembourg, and Malta). The twenty-one Western countries considered are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, and US. The eleven CEE and Baltic countries are: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

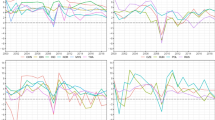

As illustrated by Fig. 2, there is a clear negative and statistically significant relationship between the real effective exchange rate (REER), a proxy for price competitiveness, and export-led growth for the twenty-one advanced Western countries in the pre-crisis period. The REER is a trade-weighted measure of price competitiveness: if it increases, domestic prices are growing faster than in trade partners and a decline of competitiveness is expected. However, there is no statistical association between these two variables for the eleven CEE/Baltic countries in the same period. The relationship between REER and export-led growth disappears for advanced Western countries as well in the post-crisis period. In the post-crisis period, the growth contribution of exports becomes much smaller than in the previous period. For CEE/Baltic countries, REER continues to be an insignificant predictor in the post-crisis period as well.Footnote 5

The second bivariate relationship examined is between export-led growth and an index of economic complexity (not available for Cyprus and Iceland). The index, described in Appendix Table 7, is based on disaggregated trade data at the product and export market level and captures both the diversification of export products and destination markets. Kohler and Stockhammer (2021) use it as an indicator of non-price competitiveness of exports (see also Gräbner et al. 2020). A country with a highly diversified product portfolio and export markets has a higher economic complexity score and is expected to have better export performance. However, we find no significant correlation between the economic complexity index and export-led growth among advanced Western countries in the pre-crisis period. The regression line is positive as expected, but the countries are scattered across the two-dimensional plane. The relationship is instead more clearly positive but significant only at the 10% level for CEE countries in the pre-crisis period. In the post-crisis period, the relationship is clearly insignificant for both advanced Western and CEE countries. Overall, economic complexity does not seem to be a robust driver of export-led growth.Footnote 6 All four plots relating to the link between the economic complexity index and growth contributions of exports are available in Appendix C, Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9.

To disentangle the effects of different determinants, we use regression analysis. We focus on the advanced Western countries due to the small sample size for CEE countries. The dependent variable is the growth contribution of import-adjusted exports. The independent variables are the REER and the proxy for non-price competitiveness. We also test whether the magnitude of export-led growth contributions is positively related to the growth of foreign demand, alone and in interaction with non-price competitiveness. If a country’s exports have high complexity, they should be able to capture a larger share of expanding foreign markets than a country with low levels of export complexity.Footnote 7

The regression results for 1995–2007 (Table 4) confirm the results of the bivariate graph above: the change in REER has a negative and highly significant impact on export-led growth, controlling for economic complexity and growth of foreign demand. The point estimate around -0.4 indicates an economically very significant effect of an average reduction of 4% in the export contribution to growth for every 10% of competitiveness loss. Economic complexity is not significantly associated with export growth either alone or in interaction with the growth of foreign demand. The results also suggest that growing foreign markets per se are not associated with higher export-led growth. It should be noted that when the growth contribution of net exports (exports minus all imports) is used as a dependent variable, as it usually is (column 3 of Table 4), the coefficient of REER is attenuated and statistically insignificant, which highlights the usefulness of using the new and more precise indicator of import-adjusted export-led growth. As already indicated by the bivariate graph, the relationship between export-led growth and REER breaks down in 2009–2018, due to many more countries, particularly the Mediterranean ones, turning towards export-led growth and the growth contributions of exports declining massively on average (Scharpf 2021). The regressions for 2009–2018 have no significant results and we do not report them here, but they can be found in Table 8, Appendix C.

8 Concluding discussion

This paper has introduced a new methodology for operationalizing growth models using the most recent IOTs made available by the OECD for a number of countries. Our methodology has the advantage of not requiring the acceptance of assumptions about the underlying structure of the economy and calculates the growth contributions of consumption, investment, government expenditures, and exports after subtracting direct and indirect imports from each of these demand components. We have used simple rules (e.g., if the relative contribution is higher than 40%, the growth model is driven by that component) to classify growth models in two periods: 1995–2007 and 2009–2018.

The results resonate with a number of stylized facts in the literature on comparative capitalism. They suggest that continental European economies were export-led before the crisis (with the exception of the Netherlands) and have further accentuated their reliance on export-led growth on average after 2008. The English-speaking LMEs instead have a very different type of growth model, being either consumption-led or domestic demand-led. In the Nordic countries, domestic demand was more important for growth even before the crisis. This is not surprising, since these are countries with large welfare states and still strong labor movements, which increases the domestic orientation of the growth process. After the crisis, the Nordic countries have been boosting the contribution of domestic demand, moving further way from the continental group. The Mediterranean countries were domestic demand-led before the crisis but were forced by the euro crisis to reorient their growth profile towards export-led (Perez and Matsaganis 2019; Scharpf 2021). As a result, their domestic demand has collapsed and the only positive contribution to growth has come from exports, even though the absolute growth contribution of exports has been low in these countries. The CEE countries were already export-led before the crisis, with the exception of the Baltics, and have become even more so after the crisis.

Interestingly, our indicators also highlight interesting variation within regions. For example, the Netherlands had a more balanced growth model in the pre-crisis period than the other continental countries, but responded to the crisis by strongly accentuating its export profile. The Denmark appears an exception among Nordic countries, being the only export-led economy in the region. Romania was considerably more domestic demand-led than other CEE countries in the pre-crisis period. We have refrained from commenting on the growth model results of countries for which we lack substantive knowledge (especially the emerging ones). We hope the data we have provided and the patterns we have pointed to will inform the work of country and regional specialists. One potentially useful approach that can be linked to the growth model perspective is the inclusive growth framework, which links economic growth to economic inequality by emphasizing the need to raise the living standards of all social strata in order to achieve growth (Cerra 2021). Recent research has also shown that institutions play a key role in achieving inclusive growth (Aslam et al. 2021; Aslam 2020).

In a further step, we have used the data to address the question of the role that price- and non-price competitiveness play in export-led growth. Although this part aims to illustrate the potential of this kind of approach, more than providing definitive answers, we were able to reveal some interesting empirical patterns. Cost competitiveness, captured by movements in the real exchange rate, is a statistically and economically highly significant determinant of export-led growth for advanced Western countries in the pre-crisis period. However, it does not play any role for the CEE countries' export-led growth.

The methodology and data on different demand contributions to growth that we have developed in this paper open up an interesting research agenda at the intersection between comparative political economy and heterodox economics. What, for example, is the role of partisanship in determining the prevalence of different types of growth? Do labor market, welfare state, and financial institutions have a differential impact on growth models? To what extent do trade and financial interdependencies affect growth models at the country level? We hope that other scholars will join us in exploring these and other questions.

Notes

Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Laos, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Malta, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taipei, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, UK, US, Vietnam.

IOTs set the direct imports of exports (defined as the short-term transit of goods and services in an intermediary country without undergoing any value-adding processes) to zero. Existing research relying on IO tables argues that this is a plausible assumption in advanced countries (e.g., Auboin and Borino 2018; Bussière et al. 2013). However, empirical analyses suggest that the assumption may not be warranted (Guo et al. 2009). Therefore, if direct imports of exports are set to zero, their corresponding values when they are re-exported should also be excluded from exports. Working with WIOD IO Tables and the previous OECD releases of IOTs prior to the latest OECD release, we notice that for certain countries (the Netherlands and Belgium in particular) the growth contribution of exports reaches extreme values that suggest overestimation due to re-exports not being netted out from exports.

For Ireland, even GNI is no longer a valid measure. This is due to multinational IT and pharmaceutical companies, or aircraft leasing companies, locating their intellectual property (which is classified as investment) in Ireland in order to take advantage of a favorable tax regime (Tedeschi 2018). The Irish Central Statistical Office now prefers to use a modified GNI measure net of depreciation on these two classes of assets.

For Greece and Brunei, the average growth rate 2009–2018 is negative. Thus, it makes little sense to determine the growth model of these two countries, because they are cases of degrowth. For this reason, no growth model label is attributed to these two countries in Table 2. In addition, after 2008, in several instances in other countries some demand components show negative contributions to growth. Since the relative growth contributions of the four demand components sum up to 100 percent by definition, it is possible for some components to have a contribution to growth greater than 100 percent, compensating for the negative growth share of other components. The only exceptions are Greece and Brunei after 2008, in which the sum gives -100 percent, because we have adjusted the calculation of the relative growth contributions in the case of negative GDP growth (used as denominator) so that positive/negative absolute contributions in the numerator remain positive/negative.

The indicator of economic complexity has little time variation, hence our use of the level as opposed to the change (see Kohler and Stockhammer, (2021), for a similar choice). Using the change does not alter any substantive conclusion.

The indicator of foreign demand for country i is a trade-weighted sum of import volume growth in all j countries in our database, with the weights equal to the share of exports to j in total exports of i in a baseline year (1995 for the 1995–2007 period and 2009 for 2009–2018). Substantive conclusions are robust to alternative operationalization of the foreign demand variable. Appendix B reports information on variable operationalization.

While OECD data also provide component-specific deflators, these deflators have been developed to be used with non-import-adjusted components at purchasers’ prices that are not equivalent to those we work with. Using them would in particular imply that the results we obtain would become dependent on the chosen reference year. We hence preferred to use the overall GDP deflator for all components. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the results we obtain are very similar to those we derived by experimenting with the use of component-specific deflators.

OECD deflators are only available for forty-seven of the sixty-six countries OECD data offer IO tables on. In order to consider even the remaining countries, we used deflator data from the World Bank (eighteen countries) and from Nasdaq (Taipei). The eighteen countries for which we use World Bank data are: Brunei, Cambodia, Croatia, Cyprus, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Laos, Malaysia, Malta, Morocco, Myanmar, Peru, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Thailand, Tunisia, Vietnam. Since deflator data on Taipei is missing in both OECD and World Bank data, we additionally considered the deflator data offered by Nasdaq for the geographic entity labelled “Taiwan Province of China” (labeled “Chinese Taipei” in OECD IO Tables).

References

Apaydin, F.: The politics of changing growth regime in the periphery of Europe: the case of Turkey. Unpublished manuscript. Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals. (2022)

Aslam, A.: The hotly debate of human capital and economic growth: why institutions may matter? Qual Quant. 54, 1351–1362 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-00989-5

Aslam, A., Naveed, A., Shabbir, G.: Is it an institution, digital or social inclusion that matters for inclusive growth? A panel data analysis. Qual Quant. 55, 333–355 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01008-3

Auboin, M., Borino, F.: The falling elasticity of global trade to economic activity: testing the demand channel. Center for Economic Studies (2018)

Baccaro, L., Neimanns, E.: Who wants wage moderation? Trade exposure, export-led growth, and the irrelevance of bargaining structure. West Eur Polit. 45, 1257–1282 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.2024010

Baccaro, L., Pontusson, J.: Rethinking comparative political economy: the growth model perspective. Polit. Soc. 44, 175–207 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329216638053

Ban, C., Adascalitei, D.: The FDI-led growth models of the East-Central and South-Eastern European Periphery. In: Baccaro, L., Blyth, M., Pontusson, J. (eds.) Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation, pp. 189–212. Oxford University Press, New York (2022)

Behringer, J., van Treeck, T.: Income distribution and growth models: a sectoral balances approach. Polit Soc. 47, 303–332 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329219861237

Bhaduri, A., Marglin, S.: Unemployment and the real wage: the economic basis for contesting political ideologies. Camb. J. Econ. 14, 375–393 (1990)

Blecker, R.A.: Wage-led versus profit-led demand regimes: the long and the short of it. Rev. Keynes. Econ. 4, 373–390 (2016)

Bohle, D., Regan, A.: The comparative political economy of growth models: explaining the continuity of FDI-led growth in Ireland and Hungary. Polit Soc. 49, 75–106 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329220985723

Boyer, R.: Technical change and the theory of “regulation.” In: Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., Soete, L. (eds.) Technical change and economic theory, pp. 67–94. Pinter, London (1988)

Boyer, R., Saillard, Y. (eds.): Regulation theory: the state of the art. Routledge (2005)

Bulfone, F., Tassinari, A.: Under pressure. Economic constraints, electoral politics and labour market reforms in Southern Europe in the decade of the Great Recession. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 509–538 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12414

Bürgisser, R., Di Carlo, D.: Blessing or curse? The rise of tourism-led growth in Europe’s Southern Periphery. J. Common Mark. Stud. 61, 236–258 (2023)

Bussière, M., Callegari, G., Ghironi, F., Sestieri, G., Yamano, N.: Estimating trade elasticities: demand composition and the trade collapse of 2008–2009. Am Econ J Macroecon. 5, 118–151 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.5.3.118

Cardenas, L., Arribas, J.: Institutional change after the great recession: European growth models at the crossroads. Routledge, London New York (2021)

Cerra, V.: An inclusive growth framework. In: Cerra, V., Eichengreen, B., El-Ganainy, A., Schindler, M. (eds.) How to achieve inclusive growth. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2021)

Dietzenbacher, E., Los, B., Stehrer, R., Timmer, M., de Vries, G.: The construction of world input-output tables in the WIOD project. Econ. Syst. Res. 25, 71–98 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/09535314.2012.761180

Ergen, T., Kohl, S., Braun, B.: Firm foundations: the statistical footprint of multinational corporations as a problem for political economy. Compet. Change. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294221093704

Erixon, L., Pontusson, J.: Rebalancing balanced growth: the evolution of the Swedish growth model since the mid-1990s. In: Baccaro, L., Blyth, M., Pontusson, J. (eds.) Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation, pp. 268–292. Oxford University Press, New York (2022)

Ferrera, M.: The “Southern Model” of welfare in social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy. 6, 17–37 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879600600102

Girardi, D., Pariboni, R.: Long-run effective demand in the US economy: an empirical test of the Sraffian Supermultiplier model. Rev. Political Econ. 28, 523–544 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2016.1209893

Girardi, D., Pariboni, R.: Autonomous demand and the investment share. Rev. Keynes. Econ. 8, 428–453 (2020). https://doi.org/10.4337/roke.2020.03.07

Gräbner, C., Heimberger, P., Kapeller, J., Schütz, B.: Is the Eurozone disintegrating? Macroeconomic divergence, structural polarisation, trade and fragility. Camb. J. Econ. 44, 647–669 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bez059

Guo, D., Webb, C., Yamano, N.: Towards harmonised bilateral trade data for inter-country input-output analyses: statistical issues. OECD, Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers (2009). https://doi.org/10.1787/226023512638

Haffert, L., Mertens, D.: Between distribution and allocation: growth models, sectoral coalitions and the politics of taxation revisited. Socioecon. Rev. 19, 487–510 (2021)

Hall, P.A., Soskice, D. (eds.): Varieties of capitalism: the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2001)

Hassel, A., Palier, B.: Tracking the transformation of growth regimes in advanced capitalist economies. In: Hassel, A., Palier, B. (eds.) Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: how have growth regimes evolved?, pp. 3–56. Oxford University Press, New York (2021)

Hein, E., Meloni, W.P., Tridico, P.: Welfare models and demand-led growth regimes before and after the financial and economic crisis. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 28, 1196–1223 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1744178

Hope, D., Soskice, D.: Growth models, varieties of capitalism, and macroeconomics. Polit. Soc. 44, 209–226 (2016)

Hopkin, J.: Anti-system Politics: the crisis of market liberalism in rich democracies. Oxford University Press, New York (2020)

Höpner, M.: The German undervaluation regime under Bretton Woods: how Germany became the nightmare of the world economy. Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG) (2019)

Hübscher, E., Sattler, T.: Growth models under austerity. In: Baccaro, L., Blyth, M., Pontusson, J. (eds.) Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation, pp. 401–419. Oxford University Press, New York (2022)

Hübscher, E., Sattler, T., Truchlewski, Z.: Three worlds of austerity: voter congruence over fiscal trade-offs in Germany, Spain and the UK. Socioecon. Rev. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwac025

Johnston, A., Regan, A.: Introduction: is the European union capable of integrating diverse models of capitalism? New Polit. Econ. 23, 145–159 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1370442

Kohler, K., Stockhammer, E.: Growing differently? Financial cycles, austerity, and competitiveness in growth models since the Global Financial Crisis. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1899035

Krampf, A.: The Israeli path to neoliberalism: the state, continuity and change. Routledge (2020)

Lavoie, M., Stockhammer, E.: Wage-led growth: concept, theories and policies. In: Lavoie, M., Stockhammer, E. (eds.) Wage-led growth: an equitable strategy for economic recovery, pp. 13–39. Palgrave Macmillan, London (2013)

Linsi, L., Mügge, D.K.: Globalization and the growing defects of international economic statistics. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 26, 361–383 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1560353

Mertens, D., Nölke, A., May, C., Schedelik, M., Brink, T. ten, Gomes, A.: Moving the center: adapting the toolbox of growth model research to emerging capitalist economies. Berlin School of Economics and Law, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE) (2022)

Miller, R.E., Blair, P.D.: Input-output analysis: foundations and extensions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2009)

Minsky, H.P.: The financial instability hypothesis. The Jerome Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Rochester (1992)

Nölke, A., May, C., Mertens, D., Schedelik, M.: Elephant limps, but jaguar stumbles: unpacking the divergence of state capitalism in Brazil and India through theories of capitalist diversity. Compet. Chang. 26, 311–333 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294211015597

Nurunnabi, M.: Transformation from an oil-based economy to a knowledge-based economy in Saudi Arabia: the direction of Saudi vision 2030. J Knowl Econ. 8, 536–564 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-017-0479-8

Perez, S., Matsaganis, M.: The political economy of austerity in Southern Europe. New Polit. Econ. 23, 192–207 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1370445

Perez, S., Matsaganis, M.: Export or perish: can internal devaluation create enough good jobs in Southern Europe? South Eur. Soc. Polit. 24, 259–285 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2019.1644813

Picot, G.: Cross-national variation in growth models: three sources of extra demand. In: Hassel, A., Palier, B. (eds.) Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: how have growth regimes evolved?, pp. 135–160. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2021)

Pontusson, J.: Inequality and prosperity: social Europe vs. liberal America. Cornell University Press, Ithaca (2005)

Ragin, C.C.: Fuzzy-set social science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2000)

Reisenbichler, A.: The politics of quantitative easing and housing stimulus by the federal reserve and European Central Bank, 2008–2018. West Eur. Polit. 43, 464–484 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1612160

Reisenbichler, A., Wiedemann, A.: Credit-driven and consumption-led growth models in the United States and United Kingdom. In: Baccaro, L., Blyth, M., Pontusson, J. (eds.) Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation, pp. 213–237. Oxford University Press, New York (2022)

Riedel, J., Jin, J., Gao, J.: How China grows: investment, finance, and reform. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2007)

Scharpf, F.: Forced structural convergence in the Eurozone. In: Hassel, A., Palier, B. (eds.) Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: how have growth regimes evolved?, pp. 161–200. Oxford University Press, New York (2021)

Schmidt, V.A.: The futures of European capitalism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York (2002)

Sierra, J.: The politics of growth model switching: why Latin America tries, and fails, to abandon commodity-driven growth. In: Baccaro, L., Blyth, M., Pontusson, J. (eds.) Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation, pp. 167–188. Oxford University Press, New York (2022)

Stockhammer, E., Kohler, K.: Learning from distant cousins? Post-Keynesian economics, comparative political economy, and the growth models approach. Rev. Keynes. Econ. 10, 184–203 (2022)

Stockhammer, E., Wildauer, R.: Debt-driven growth? Wealth, distribution and demand in OECD countries. Camb. J. Econ. 40, 1609–1634 (2016)

Storm, S., Naastepad, C.W.M.: Macroeconomics beyond the NAIRU. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (2012)

Tedeschi, R.: The Irish GDP in 2016. After the disaster comes a dilemma. Bank of Italy (2018)

Acknowledgements

We thank Timur Ergen, Peter Hall, Martin Höpner, Arie Krampf, Erik Neimanns, Andreas Nölke, and Saila Stausholm for helpful comments on an early draft of this paper. An early draft of this paper has been published as a working paper (MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 22/6), available here: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/265505/1/1820191346.pdf.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix A: Derivation of indirect imports through input–output tables

In this appendix, we describe the steps used to derive the indirect imports, sector by sector, for each demand component using the OECD national Input–Output Tables (1995–2018). The procedure follows Auboin and Borino (2018, pp. 36–38).

The raw national IO tables used to derive import-adjusted growth contributions are provided in the form of excel or csv sheets, each one containing data about a given country in a given year (country-year data). For every country-year, original data come in the form of five block matrices, organized as follows (Table 5).

All data are provided at basic prices (except “total intermediate consumption at purchasers’ prices”) and expressed in current US dollars. We convert these prices into local currency by multiplying the original values with the country-year-specific exchange rates provided alongside the 2021 release of the OECD Inter-Country Input–Output Tables (ICIOs), covering all sixty-six countries between 1995 and 2018. We then deflate these values, expressed in national currency, through the deflators available in the OECD Economic Outlook data for total GDP by setting 1995 as reference year.Footnote 8,Footnote 9 We then reduce the size of the block matrices. From the original ten final demand expenditures (two columns being imports and total, which we do not use), we computed the vectors with final demand expenditures for consumption, government spending, investment, and exports from the original OECD IO Tables as follows:

By summing up together the corresponding rows and columns, we also merge the initial forty-five sectors into six economically meaningful and relatively homogeneous macro-sectors. The merging into macro-sectors could be implemented even subsequently after performing the matrix operations we describe below. We prefer to merge sectors immediately because this offers some advantages in terms of the numeric approximation implied by the computation of an inverse (the Leontief inverse) in one of the following steps. As with every statistical software, the inverse is computed through numerical methods that always imply a certain amount of approximation in the final result. By reducing the dimensions of the matrix to be inverted (6 × 6 in this case instead of 45 × 45), we reduce the impact of these approximations. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the results we obtain by merging sectors immediately (as we did in this paper) or subsequently are virtually equivalent and the small differences that appear do not have any influence on the substantive empirical patterns we describe in the paper.

We hence obtain the following reduced block matrix structure (Table

6).

On this modified input–output table, for every country-year, we perform the following calculations. First, we transform the matrices Zd and Zm into the matrices Ad and Am by dividing each cell of Zd and Zm by the sum of the respective column (total output of sector j).

Second, we express the domestic output of sector i that satisfies the final demand component k as follows:

In matrix form:

Third, for each final demand component k, we calculate the imports of intermediate inputs from sector i induced by domestically produced products and services satisfying the demand component k with the following formula:

This formula tells us that each sector i uses the sum of imported inputs from sectors j (\(z_{i,j}^{m} = a_{i,j}^{m} x_{j}\)) to produce its output. In matrix form:

Plugging the formula for \(X\) into the formula for \(M^{ind}\):

Mind is a 6 × 4 matrix which indicates, sector by sector, the indirect imports associated with each component of final demand.

Appendix B: Auxiliary variables and structural determinants of growth

Appendix C: Additional figures and tables

Appendix D: Empirical validation of relative growth contribution thresholds to classify growth models

In this Appendix, we provide an empirical validation of the relative growth contribution thresholds we used in the main text to classify growth models. Our empirical investigations are based primarily on two observations. First, as the values in Table 2 show, we are confronted with growth contributions from various demand components that exhibit a wide range of values. In particular, several strong outliers occur in the post-2008 period, related to the fact that countries with growth close to zero or negative often have relative growth contributions of more or less than 100%. Therefore, if we want to derive empirically based thresholds, it is useful to rely on indicators that are robust to outliers. We focus on three indicators of the distribution of relative growth contributions that divide countries into two equal groups (the median) and identify the bottom third (the 33.3% percentile) and the top third (the 66.6% percentile) of the 132 country-periods (sixty-six countries observed over two periods) included in our analyses. Second, as can be seen from the empirical patterns described in the text, the crucial dichotomy that distinguishes the growth models of different countries and regions is the distinction between domestic demand-led and export-led growth.

Taking these two considerations into account, we have calculated the median, the 33.3% percentile, and the 66.6% percentile of the relative contribution of exports to growth (and, implicitly, also the relative contribution of domestic demand to growth, since it is the complement of that) for the 132 country-periods over which we have data.

The median value we obtain taking into account all country-periods is 39.9% (in-between Poland and Tunisia pre-2008). This shows that the threshold described above for defining whether a growth model is "led" by exports or any other component (40%) is almost the same as the median value for distinguishing between export- and domestic demand-led growth.

Repeating the same exercise and focusing on the 33.3% and 66.6% percentiles, we find that the two values separating the bottom and top thirds of relative growth contributions of exports for all country-periods are 30.7% (in-between the values of China and Laos pre-2008) and 54.5% (in-between the values of Slovakia and Kazakhstan pre-2008), respectively. The first value is very close to the threshold we used to determine a balanced growth model (30%). The second value is close to the threshold (50%) we used to define when growth is "strongly" dependent on a particular demand component. However, the 50% mark is a focal point that makes us prefer it to the purely empirical 54.5% value of the 66.6% percentile.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baccaro, L., Hadziabdic, S. Operationalizing growth models. Qual Quant 58, 1325–1360 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-023-01685-w

Accepted:

Published: