Abstract

Thriving entrepreneurship is a necessary condition of long-term sustainability in all modern economies. However, many entrepreneurs-to-be fail to take real actions in their transition from dreamers to doers. In this paper, we demonstrate that there are significant gaps in the current understanding of the important pre-entrepreneurship stages of starting new companies. In particular, these gaps include a proper understanding of moderators such as procrastination, commitment, and acquiring entrepreneurial knowledge from informal and unstructured sources. A promising way to fill these gaps is researching a promising yet little-known group – wantrepreneurs. Our qualitative study of a group of wantrepreneurs who seriously consider becoming entrepreneurs but fail to take any concrete steps allowed us to propose a number of hypotheses in this area and propose an extension of the Entrepreneurial Event Model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The notion of wantrepreneurship has been widely recognised in the popular and so-called motivational literature, although sometimes with an ironic tint. The wantrepreneur is depicted as someone who is forever planning to start a company but fails to act on those plans (Lofrumento, 2015). To the best of our knowledge, wantrepreneurship has received surprisingly little rigorous scientific analysis (with the notable exceptions of Shaqiri & Sula, 2015 and Stoianov, 2016). In their qualitative study, Gur & Mathias (2021) observed that wantrepreneurs (also referred to by their interviewees as “idea folks”, “people with plans”, or “entrepreneur wannabes”) are typically contrasted with actual entrepreneurs. In this paper, we argue that not only should we view wantrepreneurship as a distinct point on the continuum that spreads from non-entrepreneurs to entrepreneurs, but that taking a closer look at a group of wantrepreneurs allows us to gain a more nuanced understanding of the process of new venture creation. Since these individuals remain on the border of deciding to start or not start a company for an extended period, such research allows us to elucidate in unprecedented detail the mechanisms of the entrepreneurial start-up process.

The mainstream of small business studies treats entrepreneurship as a phenomenon that spreads gradually from non-entrepreneurs, through nascent, novice, and experienced entrepreneurs, habitual (serial and portfolio) entrepreneurs, to the final stage of former entrepreneurs. Surprisingly, relatively little is known about what happens between the first and second stages, i.e., between being a non-entrepreneur and registering the first business. The existing studies try to apply the available theories in a one-size-fits-all manner (Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014, González-López et al., 2021), but predominantly without looking at the specifics of the entrepreneurial process. The entrepreneurial process is different from most other action processes in multiple dimensions, including the extraordinarily high level of complexity, the need to use external resources, its extended duration, the emotional investment, and uncertain results (Van Gelderen et al., 2015, Klyver et al., 2020).

However, this does not mean that there is a scarcity of research aimed at verifying one of the dominant theories, chiefly the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1985, 1991, 2011), the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1980), or Action Phase Theory (Gollwitzer, 1990, 1996, 2012). On the contrary, numerous attempts have been made to apply these theories to explain the process of moving from inaction to action in starting new businesses (see Liñán & Fayolle, 2015 for a thorough critical review of the vast literature in this area). However, in this paper, we argue that a more nuanced understanding and an advancement in theory are needed to take into account the specific aspects that distinguish starting a business from many other types of decisions. We argue that the founding of a new venture is fundamentally different from most other decisional situations, as it is a unique amalgamation of decision-making, information acquisition, risk-taking, career choice, overcoming and managing emotions, like fear and procrastination, as well as rationally evaluating alternative business models. As a result, the set of factors that can both facilitate and hinder this process is unique and fundamentally differs from factors that play a role in processes that are simpler and spread over a shorter time span.

In this paper, we spotlight a new, under-researched stage of the entrepreneurial path that starts from non-entrepreneurs, through nascent and experienced entrepreneurs, to serial and portfolio businesspeople. We call the stage between non-entrepreneurs and nascent entrepreneurs wantrepreneurship and argue that researching a group of wantrepreneurs in more detail could largely enhance our understanding of how businesses are started and what actually hinders this process. To illustrate the potential of this group in addressing the issues that remain open or unresolved in the current research agenda, we present the results of a qualitative study that allowed us to formulate potentially interesting, new research questions.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, we present a review of the literature concerning the formation of entrepreneurial intentions, the role of action planning in transitioning from intentions to actions, and the factors that moderate the link between entrepreneurial intentions and actions. In the next section, we outline issues that, in our view, remain open in the current research agenda and formulate hypotheses that researching wantrepreneurship could help to verify. In section four, we show results of qualitative research on a group of wantrepreneurs, which allowed us to formulate propositions that are, to the best of our knowledge, novel in the area of pre-entrepreneurship research. We present arguments that the careful examination of wantrepreneurs can substantially enhance our understanding of the transition from non-entrepreneurs to nascent entrepreneurs, and illustrate it with the results of the empirical study. The last section concludes.

2 Review of the related literature

Entrepreneurship is an intentional behaviour that largely relies on plans (Krueger et al., 2000, Dabić et al., 2021). While entrepreneurial action, such as starting a new business, is best predicted by intentions toward entrepreneurial behaviour (Bird, 1992, Davidsson et al., 2021), intentions and plans do not always result in behaviour (Krueger & Carsrud, 1993). In a meta-analysis, Gollwitzer & Sheeran (2006) found that intention strength explained only 28% of the variance in behaviour. Studies performed directly in the area of entrepreneurial behaviour yield a similarly pessimistic view. Empirical research suggests that entrepreneurial intentions explain at best 30% of the variance in entrepreneurial behaviour (Kautonen et al., 2015; Shirokova et al., 2016, Davidsson, 2021). Van Gelderen et al. (2015) reported that more than two-thirds of a sample of 161 individuals who declared entrepreneurial intentions at the beginning of a two-wave study took no action within the next year. Hence, there is an urgent need to explain (the weakness of) the link between intentions and behaviour in the area of entrepreneurship. So far, this need has been approached from several angles.

2.1 The formation and significance of entrepreneurial intentions

The creation of new ventures is the result of entrepreneurial intentions and subsequent actions (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006). A number of theories have been proposed to explain the process that starts with antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions, the development of those intentions, and an individual moving forward to actions that (possibly) result in creating a new firm. The most prominent are the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991, 2011), the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), the Entrepreneurial Event Model (Shapero & Sokol, 1982), and Action Phase Theory (Gollwitzer, 1996, 2012). Of the intention-action theories that were put forward to explain and predict behaviour, probably the most prominent is the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). According to the TRA, attitude toward the behaviour is the main factor that determines goal intentions. Attitude is understood as “the degree to which the individual has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation of the behaviour in question, and subjective norms, which refers to the perceived social pressure to perform the behaviour” (Kolvereid & Isaksen 2006). Another important theory is the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), which can be viewed as an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action, in which the perceived behavioural control forms an additional antecedent of intentions.

Among the antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions, personal attitudes are an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of a behaviour (Ajzen 1991). If the attitude toward starting a company is positive, the individual is likely to have stronger intentions to act (Joensuu-Salo et al., 2015). Subjective norms, in turn, can be thought of as the perceived social pressure to become or not become an entrepreneur (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). They can be viewed as beliefs about whether important persons from the individual’s close circle support the creation of a new venture (Ajzen, 1991). Pruet et al. (2009) operationalised the important peers as family, friends and publicly known role models who have started their own businesses. The third factor – perceived behavioural control – is the perceived ease or difficulty of becoming an entrepreneur. The latter is strongly related to the concept of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the Entrepreneurial Event Model (Shapero, 1984) – an alternative to the Theory of Planned Behaviour, designed to explain how entrepreneurial intentions translate into actions (Bandura, 1986, Gieure et al., 2019).

Numerous studies have been carried out to test the empirical implications of both theories. Kolvereid (1996), using a sample of 128 Norwegian undergraduate business students, found that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control have a significant impact, both in statistical and practical terms, on entrepreneurial intentions. Tkashev and Kolvereid (1999) confirmed these findings on a sample of 512 Russian students. Armitage and Conner (2001), in turn, presented a meta-analysis of 161 studies, finding, on average, high and statistically significant relationships between entrepreneurial intentions and attitude toward entrepreneurship and perceived behavioural control, with a slightly weaker significance of subjective norms.

2.2 The distinct role of entrepreneurial action planning

While the role of pure intentions should not be undervalued, it is action that is crucial for new venture creation. Starting a new venture involves actions aimed at gathering the resources and developing business structures (Gartner, 1985). Empirical research has shown that individuals who successfully made the transition from wantrepreneur to entrepreneur show more action (Carter et al., 1996) and engage in more entrepreneurial activities in comparison to those who remained merely in the wantrepreneurship domain (Kessler and Frank, 2009).

The literature on entrepreneurship offers several theoretical frameworks to elaborate on the role of entrepreneurial action in starting a new venture. Probably the most prominent is Action Regulation Theory, developed by Hacker (1986) and applied to entrepreneurship by Frese (2009), which puts in the spotlight implementation intentions (Gollwitzer, 1999) or action plans (Frese, 2009). It is closely related to the Theory of Planned Behaviour, but while, in the context of small business, the TBP is focused on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions, Action Regulation Theory takes intentions as the starting point. It elucidates its aftereffects while taking a more granular view of the transition from intentions to actions.

The starting point is the goal intentions that specify what an entrepreneur wants to achieve (Bird 1988, Locke & Latham 2002). However, goal intentions are not enough (Frese and Zapf, 1994; Gollwitzer, 1999). Action Regulation Theory emphasises the role of action plans that transform pure goal intentions into concrete actions. In order to start an action, the wantrepreneur needs to outline the sequence of steps necessary to reach the desired state (Mumford et al., 2001). Sniehotta et al. (2005) defined action planning as “the process of linking goal-directed behaviours to certain environmental cues by specifying when, where, and how to act.” According to Gollwitzer (1996), in the process of planning, “individuals reflect and decide on the when, where, how, and how long to act”. This results in conditional plans of action (“if the market analysis yields positive results, I will order a prototype”), which specifies conditions (when and where to act) and behavioural responses (how to act) in advance (Gollwitzer, 1999). However, Gelderen et al. (2015) advocate for a broader understanding of action plans, and also include in this definition the unconditional form (“I will order a qualitative market study”).

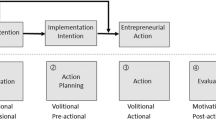

The importance of action plans takes the central role in another prominent theory that is widely used to understand the course of entrepreneurial behaviour – Action Phase Theory (APT), proposed by Gollwitzer (1996, 2012). In any action, including starting a new venture, APT identified four action phases. In the pre-decisional phase, an individual defines the goals she wants to pursue. In the next phase, implementation intentions are specified: the nascent entrepreneur chooses the optimum path to the desired goal and methods that best support this path. Implementation intentions can be thus viewed as very closely related to action plans and many researchers use these terms interchangeably (Adriaanse et al. 2011). Then an individual enters the third phase, in which the entrepreneurial action takes place. In the fourth phase, individuals review the results and start to plan future actions (Achtziger and Gollwitzer 2008). This process is iterative, as the main objective (e.g., starting and running a company) is typically divided into many smaller pieces, each of which includes forming an objective, preparing action plans, taking action and evaluating.

The effect of action plans as a moderating factor between entrepreneurial intentions and actions found some empirical support. Van Gelderen et al. (2018), using data from the survey of 422 Swedish wantrepreneurs, confirmed that there is a sizeable moderating effect of action plans on entrepreneurial behaviour. Outside the entrepreneurship domain, Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2006) presented a meta-analysis of 94 independent tests from 63 reports and showed that implementation intentions exerted a strong effect on achieving goals. In their study, however, action plans were treated as direct antecedents of actions rather than being used as a moderator. Also, it is not clear to what extent their result can be applied to the entrepreneurship area, which typically involves complex and long-term actions.

2.3 Moderating factors

Theories of planning, albeit insightful in general, tend to focus on the mechanism of initiating the action itself. A broad strand of research supplemented them with a set of action-regulatory factors that stimulate or inhibit entrepreneurial action (Karoly, 1993). These factors can exert a direct influence on action, as well as serve as a moderator in a trajectory that leads from TPB-based antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions, through goal intentions and action plans to the actions themselves.

Gielnik et al. (2014) were among the first who theorised on the role of positive fantasies in shaping an intention-behaviour relationship in starting a new venture. Positive fantasies are a cognitive construct concerning the positive future outcomes of the individual’s actions. They can be thought of as daydreams, such as thinking about the power or income related to being a businessperson. Positive fantasies differ from other types of thinking about the future, such as projections based on past performance (Oettingen & Mayer, 2002), as they are generally not based on rational grounds, but rather on pure preferences. Gielnik et al. (2014) argued that positive fantasies exert a negative impact on action. In a study of 96 individuals in Uganda Oettingen & Mayer (2002) confirmed that positive fantasies indeed have a negative impact on venture creation.

Abraham & Sheeran (2003) and Neneh (2019) theorised that there are also other factors that could interact with action plans and thus impact the rate of new venture creation among wantrepreneurs. Neneh’s study focused on two factors that the theory suggests as having a significant impact on human action: anticipated regret and proactive personality. Anticipated regret is the negative emotional reaction that results from comparing the expected state after the decision to refrain from action to the state after actually having taken the action (Loewenstein & Lerner, 2003, Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). Proactive personality, in turn, is a trait that increases the likelihood that an individual actually takes action instead of accepting the status quo and believes in her ability to change it (Bateman & Crant, 1993). Given the difficulties associated with entrepreneurial action and the motivation required to overcome them, these two forward-looking factors can potentially play an important role in moderating the effect of entrepreneurial intentions on actions. In a study of 277 respondents in two waves of survey data, Neneh (2019) showed weak evidence—in terms of statistical significance—that both factors positively influence the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and new venture creation.

In comparison to earlier studies, Bogatyreva et al. (2019) took a novel empirical approach and used a wide international dataset to examine the role of nationwide cultural traits that influence entrepreneurial action. Among the analysed factors, they analysed cultural parameters like individualism, masculinity, indulgence, long-term orientation, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance. Using data from two waves of the multi-country Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ survey, they showed that most of the measured cultural characteristics had a significant, negative impact on the transition from wantrepreneur to starting new ventures. Bogatyreva et al. (2019) also added an important dimension to the ongoing discussion by showing that cultural context plays an important role in entrepreneurs’ professional trajectories.

3 Open issues concerning the intention-action link in entrepreneurship

The question of why some people but not others decide to start a company have long been addressed by small business and entrepreneurship scholars (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). A broad strand of research has been devoted to analysing the antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions (Schlaegel & Koenig 2014) and measuring the link between intentions and real actions (Gielnik et al. 2014, 2015; Kautonen et al. 2015; Obschonka et al. 2015; Rauch and Hulsink 2015; Van Gelderen et al. 2015). The latter resulted in the observation of a pattern that seems consistent across countries and time: a large part of those who intend to fund a venture later do not follow up on this intention. This intention–behaviour gap can be considered a form of social waste, as a considerable amount of human time and energy does not transform into tangible results. On the other hand, the decision not to start a company may be seen as a necessary process of adjustment, saving the economy from even higher costs of ill-designed investment projects.

Several studies have addressed the intention–action gap in the entrepreneurial context, taking the Theory of Planned Behaviour, the Entrepreneurial Event Model, and Action Phase Theory as theoretical frameworks. However, despite the recent advancements in the field, several issues remain unresolved. Below we discuss several factors that have not been, to the best of our knowledge, considered moderators in the process of transitioning from the stage of wantrepreneurship to doing actual business, although they have a proven role in different aspects of entrepreneurship.

In particular, this refers to the mechanisms of procrastination and commitment that may, respectively, impede and reinforce the creation of a new business venture. Further, we discuss the rational, non-professional evaluation of potential business models and its interplay with emotional aspects of entrepreneurial decision-making. Lastly, we turn our focus to the role of informal learning in making the decision to start a new venture. This allowed us to specify three hypotheses (H1–H3) concerning the role of these factors as moderators in the process of moving from entrepreneurial intentions to actions. Similar hypotheses have been tested to some extent for the samples of nascent entrepreneurs. However, we believe that testing them for samples that include wantrepreneurs may shed new light on this intricate process and may be conducive to designing policy tools that foster the creation of new ventures.

3.1 Procrastination and fear of failure as impediments to starting a business

Procrastination is a phenomenon that has been well researched in the psychological literature but one that has drawn surprisingly little attention from researchers from the area of entrepreneurship. While the uniformly accepted definition of procrastination still does not exist, it is widely understood as an inability to act upon one’s intentions in a timely manner (Klingsieck et al., 2013). Procrastination differs from intentional (strategic) delay in that it is irrational and often accompanied by subjective discomfort, such as guilt. Verbruggen & De Vos (2020) recently proposed the Theory of Career Inaction as a way to include the prominent role of procrastination in important career-related decisions (Siaputra, 2010). However, this attempt is related to a professional career, in general, while less so in relation to the role of procrastination in entrepreneurship. It is an important gap in understanding the process of becoming an entrepreneur since the process of making a decision and planning concrete actions in starting a company is long, complex, and full of feedback loops. Thus, the standard studies of procrastination in simple everyday events that prevail in the literature do not provide sufficient insight. We see a need to fill this gap and provide an in-depth analysis concerning the interplay between entrepreneurial intentions, personal traits, and procrastination that happen in the process of action planning. In particular, there is a need to incorporate procrastination in the Action Phase Theory and to elaborate on the methodology to discriminate the effects of procrastination from the results of action delay and the rational evaluation of unfeasible business models.

Besides procrastination, fear of failure is another factor that comes into play in starting new ventures. It is widely known that most new ventures end in failure (Knott & Posen, 2005), and this process has been widely researched in the literature (e.g., Holmberg, & Morgan, 2003; Arenius and Minniti, 2005; Shepherd, 2003). Fear of failure is viewed as a factor that negatively impacts entrepreneurial action (Hatala 2005; Bosma et al., 2007). Empirical studies generally confirm that high levels of fear of failure are negatively correlated with subsequent entrepreneurial activity (Arenius and Minniti, 2005; Langowitz and Minniti, 2007). However, its specific role in shaping the link between actions and intentions are unknown, which led us to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Procrastination negatively moderates the link between entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour.

3.2 The role of commitment

The role of commitment in taking action is also relatively well-researched in psychology, but important conclusions from existing studies are not easily applicable to the laborious process of creating a new venture. Commitment, in line with Becker’s (1960) “side-bets” concept, is understood in the organisational context as a number of accrued investments that would be lost if an individual were to leave the organisation. This definition is easily applicable in the area of entrepreneurship: the longer the wantrepreneur gets involved in real actions related to starting a business, the more she becomes committed and the more difficult it is to take a step back.

A possible avenue for further research is to elucidate the role of commitment in becoming an entrepreneur by providing a theoretical framework and incorporating commitment into existing theories of the planning-action link. Commitment can also be included in the empirical research as one of the moderators that influence the strength of the connection between entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial behaviour. In this aspect, we propose the following working hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Commitment positively moderates the link between entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour.

3.3 Evaluation of the business models and ideas

The literature concerning the process in which entrepreneurs evaluate business opportunities and models is vast, taking into account the emotional aspects of decision making. Keh et al. (2002) stress the role of cognitive errors, such as overconfidence, a belief in the law of small numbers, planning fallacy, and the illusion of control, as well as personal traits such as risk propensity. However, most research focuses on actual entrepreneurs, with registered and operating businesses, which, at least in part, may be related to the feasibility of designing research and gathering the necessary sample.

We argue, however, that the results of the available body of research may not be easily extended to wantrepreneurial behaviour. While actual entrepreneurs already have some minimal experience in evaluating at least one business idea and bringing it to life, a wantrepreneur does not have such a background. In fact, the wantrepreneur not only faces the daunting task of choosing which business idea to pursue, but also a strong alternative of not becoming an entrepreneur at all. This makes the decision problem overwhelming and possibly qualitatively different from the decision of an entrepreneur. This creates a need to gain an empirical insight into the nature of business idea evaluation in the wantrepreneurial process and, in particular, differentiating it from the business model evaluation performed by seasoned entrepreneurs. We pursue this problem in depth in the following section, based on the exploratory, qualitative study with wantrepreneurs.

3.4 The role of informal learning

The literature concerning the role of entrepreneurial training, both formal and informal, and its impact on entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour, is abundant, both in terms of theoretical frameworks (e.g., Cope, 2005, Ferrari, 2020) and their empirical validation (Keith et al., 2016, Sharafizad, 2018, Park et al., 2019, see Anwar & Daniel, 2016 for a critical review of the literature). However, relatively little is known about the self-directed process of gaining entrepreneurial knowledge in the process of the (intended) transition from wantrepreneur to entrepreneur. While anecdotal evidence points at the notable role of social media, blogs, and amateur internet videos in gaining entrepreneurial knowledge, with the notable exception of Barczyk & Duncan (2012), little is known about the impact of these popular sources of knowledge on shaping entrepreneurial intentions and attitudes. We see a need to bridge this gap by qualitatively examining the process of using the available information sources in informal learning and the impact of this process on shaping the entrepreneurial goal intentions and concrete action plans, which could result in verification of the following working hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3

Exposure to informal entrepreneurship learning positively moderates the link between entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour.

4 Wantrepreneurs as a promising object of research – an empirical study

The available literature on the process of becoming an entrepreneur focuses on novice entrepreneurs and, by design of the dominant strand of empirical studies, puts them in the centre of analysis. This bias is largely the result of the availability of databases of entrepreneurs. Some of the most cited analyses (Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006) go so far as to treat freshly registered businesses as merely a sign of entrepreneurial intentions instead of actual behaviour. However, surprisingly little empirical research has been done about the stage when the idea to run an own company is inside the head of the originator, possibly for many years.

To address these questions in a novel way, we aim to harness the potential of a latent, vital group – wantrepreneurs. In this study, we define a wantrepreneur as someone who considers starting a new venture as a career option but who does not follow through on this intent for an extended period. Depending on which lens we view this theory through, such behaviour can be seen as reasonable inaction on a non-promising business model (the neoclassical approach to entrepreneurship), a rational decision problem concerning career choice (the Theory of Career Inaction, Verbruggen & De Vos, 2020), the effect of inadequate planning (the Theory of Planned Behaviour, Ajzen, 1991, 2011), or a procrastination-related problem (Anderson, 2003). We argue that wantrepreneurs are precisely the group that is the border between intentions, planning, and actual entrepreneurial actions, thus rendering itself particularly valuable for analysing the trajectory of becoming a fully-fledged entrepreneur.

4.1 Objectives and methods

In order to illustrate the concept that research focused on wantrepreneurs may deliver new insight into the process of starting new ventures, we performed a qualitative empirical study. We adopted a case study approach, which allowed us to investigate the validity of the integrated model. In line with Pauwels and Matthyssens (2004), we analysed the context and processes involved in wantrepreneurship. We applied pattern matching as a way of combining patterns predicted from our conceptual model with empirical phenomena. Pattern matching, which has proved very useful in case study research (Yin, 1984), involves comparing non-random objects (Trochim, 1989) and a predicted theoretical pattern with an empirical pattern (Sinkovics, 2018). We deductively analysed our empirical cases and matched them to the model, which provided the foundations for the interpretation (Pauwels and Matthyssens, 2004).

The objective of the research was twofold. First, it was to give ground to the conceptual model of wantrepreneurship and enable the hypotheses to be outlined using the grounded theory approach. Second, it was to test the cohesiveness of wantrepreneurs as a research group and to verify their ability to provide valuable research input in the context of entrepreneurship-related behaviour theories.

4.2 Setup and sample

Our research was carried out in the first quarter of 2020. It took the form of 12 semi-structured interviews with wantrepreneurs and entrepreneurs. In order to contact wantrepreneurs, we performed a search on a Polish social media group with a focus on entrepreneurship and contacted potential interviewees directly. Almost all individuals we contacted were wantrepreneurs in the sense that they were either paid employees with no previous business experience and planned to start a business, or they had some business experience and planned to start a business in an area very distant from their current business activity.

While the latter may at first seem not to belong to the group of wantrepreneurs, their stories and experiences turned out to be strikingly similar to those of individuals who had no business experience whatsoever. In fact, on being contacted for the first time, the individuals in this group entirely dismissed the notion that they have entrepreneurial experience. It was only in the course of the interview that they described their previous business experience. At the same time, the problems they had been struggling with and their stories were strikingly similar to those of ‘pure’ wantrepreneurs. Hence, we decided that they may add important information to our sample and enable us to formulate hypotheses concerning the impact of previous distant entrepreneurial experience on the path to the new business.

Each interview lasted approximately 30–40 min and was personally conducted by the author via Skype and recorded with the consent of the interviewee. The interviews were conducted in Polish, transcribed, and coded. Table 1 presents the main characteristics of each interviewee.

During the first round of coding, we read the empirical material and sought the recurring and most distinctive information in order to assign them codes. This stage was exploratory, and codes were entirely driven by the content of transcripts, in line with the grounded theory approach (open coding; Charmaz, 2006). At this stage, a set of 65 codes was developed. The codes were further classified into categories that were later subjected to clustering and reduction (axial coding), which resulted in 4 main categories. During the selective coding, we integrated the categories and their properties into the main empirical findings.

4.3 Main empirical findings

The interviews gave us an interesting insight into the process of developing the concept of becoming an entrepreneur and the informal self-education process involved. Firstly, we were able to easily find wantrepreneurs and confirm their existence. They turned out to be valuable interviewees, with, in most cases, a strong need to share their experiences, which made their stories easily retrieved. Our research confirmed that, indeed, a sizeable group of people exists who had for years (in our sample, from 6 to 36 months) considered starting a business and still found themselves at the very early stage. When asked about specific obstacles that were holding them back from taking entrepreneurial action, they predominantly pointed to insufficient knowledge (general or in a specific field), or they gave very general reasons, such as “it all takes time” or “I just haven’t started yet.” When asked an open question how they would describe their current stage on the entrepreneurial path, they almost uniformly answered “starting”, “slowly starting,” or “planning”. These descriptions entail almost no commitment, are non-binding, and hence easy to back out of. On the other hand, some of the interviewed wantrepreneurs had already made minor commitments, e.g., invested in working prototypes of their ideas or reached out to potential customers to gain their feedback. This would be in line with both hypotheses H1 (concerning procrastination) and H2 (the role of commitment); however, qualitative studies are clearly required for verification.

An interesting observation is that the interviewees had specific visions of both the business idea (business model) and the role of business in their future life (most viewed it as their future “main job”). It looks almost as if starting to think about a business is inextricably linked to the choice of a particular business idea and business model, as well as the role of business as either the main or supplementary source of income. This allowed us to formulate the following proposition:

Proposition 1

Planning to become an entrepreneur is accompanied by an idea for a specific business.

Surprisingly, in contrast to having a solid vision of the business type they want to develop, the interviewees either could not describe their action plans (neither in the if … then form advocated by Gollwitzer (1993; 1999), nor in its unconditional version), or their action plans referred to learning, reading, or other forms that do not involve commitment. It is open to further investigation whether this characteristic is a pure artifact related to the size of our sample or that there is a systematic phenomenon of people who can think of being entrepreneurs for an extended period without any action plans. It is open to quantitative investigation to see if there is a possible intervention that stimulates creating these plans and whether such an intervention would truly result in entrepreneurial action. Hence, from the practical point of view, it would be valuable to use the group of wantrepreneurs to further pursue the following proposition:

Proposition 2

Encouraging wantrepreneurs to create precise action plans is conducive to subsequent entrepreneurial action.

The next group of observations concerns the learning process. Almost all of them declared that they were actively seeking information, while some declared that learning was their primary action plan. We were able to identify two groups of interviewees based on the types of information sought. The self-reported learning behaviour of one group focused on popular self-development and so-called motivational literature: “real-life examples of successful businesses,” or “how to organise automatic processes that allow me to have more time.” The other group sought specific advice (a constantly recurring word in the statements was “concrete”) in the fields of marketing, product design, and, predominantly, the formal aspects of small business, such as taxes, registering a company, or finding the right accounting office. It would be tempting to verify whether the type of information sought is a meaningful antecedent of more direct action plans and entrepreneurial action itself:

Proposition 3

Seeking specific how-to type information is conducive to taking entrepreneurial action compared to seeking more general knowledge about entrepreneurship.

Interestingly, only one interviewee explicitly expressed the doubt “I do not know if anybody wants my product” as one of the obstacles. This is in stark contrast to the fact that, according to some studies, “no market need” is the foremost reason why modern startups fail (CB Insights, 2019). This closely corresponds to the considerations presented in Sect. 3, that the way wantrepreneurs evaluate business ideas differs significantly from the process of professional business idea evaluation. However, it may also indicate that for many wantrepreneurs, thinking of real obstacles may be just too far away from their current stage of the entrepreneurial path.

Proposition 4

The process of business idea evaluation in the wantrepreneurial context is qualitatively different from the same process undertaken by experienced entrepreneurs.

The last striking observation that can be drawn from this set of interviews is that, contrary to the bulk of available research, entrepreneurial action is a complex and multi-stage construct, the boundaries of which are not easily drawn. Many available studies concerning the link between entrepreneurial intention and action treat the latter as precisely starting a company (see, e.g., Bogatyreva et al., 2019). However, the interviews with the wantrepreneurs have shown that for them (and possibly for other entrepreneurs, too), entrepreneurial action starts well before actually registering a company. It involves acquiring entrepreneurial knowledge (which, according to our results, can be motivational, general, or highly technical), business idea generation and evaluation, and, sometimes, actually registering a company and starting “traditional” entrepreneurial activities. Also, transitions between these three stages are seldom unidirectional; in particular, there seem to be multiple transitions between the first and second stages, giving it the nature of a loop.

4.4 Discussion

The results of the qualitative study seem to confirm that wantrepreneurship offers a new and theoretically promising insight into the process of becoming an entrepreneur. Hypotheses 1 and 2 refer to forces that affect the likelihood of moving from intentions to actions: while procrastination is clearly a factor that hinders entrepreneurial actions, commitment may at least partially counterbalance this impact, as long as at least some action has been undertaken. Gur & Mathias (2021) shed some interesting light on this process by analysing the role that personal and social identities play in becoming entrepreneurs. Hypothesis 3 is related to the broad literature concerning the role of learning in becoming an entrepreneur. Although the available body of evidence generally confirms that entrepreneurship can be learned, this can be a challenge in an “unusual entrepreneurship” setup, i.e., in ventures funded by migrants or indigenous people (Burger-Helmchen, 2020).

Proposition 1

, although at first glance somewhat tautological, is in stark contrast to the approach advocated by the effectuation-focused literature (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2021, Dew et al., 2009). The latter shows that expert entrepreneurs first decide to pursue a new venture, and only then do they start to take stock of existing resources to figure out the best possible business where they could make use of these resources. Our results show that wantrepreneurs seem to start with a business idea and only then decide to become businesspeople.

Propositions 2

and 3 can be reconciled with the Action Plan Theory, which stresses the role of concrete action roadmaps as a key factor that is conducive to starting a real action. However, we could hardly observe the if-then-type plans that Gollwitzer (1999, 2012) originally considered a condition for complex actions. Instead, we found simpler one-step plans formulated by the interviewees in the “I will do XY” form. An important part of creating the action roadmaps was seeking specific how-to information. So far, despite the vast literature concerning entrepreneurial education (Gabrielsson, 2020, Gianiodis & Meek, 2020), the role of this spontaneous and informal learning, and its role in deciding to become an entrepreneur, remains relatively less known.

Both hypotheses 1–3, which stem from the available literature, and propositions 1-4, which emerged from the qualitative study, allowed us to propose an integrated conceptual model that largely builds on the existing theories, in particular Ajzen’s TPB and Gollwitzer’s APT, but extends it with new aspects. While the available models are conducive to understanding the process of new venture creation, they still give little guidance as to what exactly “takes place in the head” of a person who considers—possibly for many years—becoming an entrepreneur, who reads blogs, watches videos, listens to podcasts, and who informally evaluates multiple business ideas. What must happen so that he/she finally takes entrepreneurial action? Departing from the available models, coupled with the described shortcomings of the current state of knowledge, we propose a conceptual model that relies on the available theories, but that extends them in order to take into account a number of additional, potentially important interactions. Figure 3 shows the Extended Entrepreneurial Event Model (EEEM), which enhances the original Shapero & Sokol’s theory by the main findings concerning the wantrepreneurial process.

The EEEM spotlights what seems to be a vicious cycle in wantrepreneurship and what, in some cases, results in wantrepreneurs never actually starting a company. While a wantrepreneur may have clear goal intentions and some implementation intentions, these intentions may not be sufficiently strong to “push” him/her through all the phases of entrepreneurial action to the point where a company is registered. An individual may be stuck at the phase of acquiring knowledge or in a cycle between learning and business idea generation and evaluation, especially when the impact of existing goal intentions on actions is negatively moderated by procrastination. A wantrepreneur being stuck in the first two stages does not generate the commitment that could reinforce the entrepreneurial intentions, since merely learning and working on a business idea is not a costly activity. Hence the individual does not commit tangible resources in the entrepreneurial activity.

Clearly, this model, especially the part that is based on the qualitative study presented in this paper, requires rigorous statistical verification before it can be used to explain the transition from a non-entrepreneur to a nascent entrepreneur. In particular, verification is required before policy measures are to be designed that that would help transition an army of wantrepreneurs to fledgling entrepreneurs. However, we argue in this paper that such a group exists and constitutes an untapped potential to boost entrepreneurship and innovativeness in modern economies.

5 Conclusions & limitations

In this paper, we argued that there are considerable gaps in our knowledge about the early stages of the entrepreneurial process. In particular, these gaps relate to the determinants and moderators of the process of transitioning from entrepreneurial intentions to actions. These gaps relate to, among others, the role of procrastination, commitment, business idea evaluation, and the process of acquiring motivation and entrepreneurial knowledge, particularly from informal and unstructured sources. In our view, wantrepreneurs are a group that, at the current stage of research, opens numerous possibilities and raises a large number of questions that both challenge existing theories and may drive the development of new ones.

Clearly, this study faces important limitations. The most notable problem is the selection of interviewees and the resulting possible selection bias. It is difficult to find people who consider themselves future entrepreneurs but who have not taken any action yet. At the same time, in the sample, there may be an underrepresentation of those future entrepreneurs who tend to move fast and hence remain wantrepreneurs for a very short time. A possible yet costly way to tackle these problems is to design studies that start with the general population and involve several survey waves. Conducting such studies is clearly a promising venue for further research.

Also, the qualitative nature of the study did not allow us to draw conclusions or verify hypotheses. An important limitation of any study concerning the stage of entrepreneurship before actually registering a company is the fuzziness of the moment when a non-entrepreneur becomes a wantrepreneur since this moment may be unclear even to the wantrepreneur him/herself and also not announced to others. Also, some entrepreneurs may move particularly fast and have a very short time from ideation to entrepreneurial action, hence drastically diminishing the chance to be contacted by a researcher during the process. Thus, unless this problem is addressed directly, any sample may suffer from the overrepresentation of long-term wantrepreneurs who stay in this state for a long time and the underrepresentation of “fast” entrepreneurs who leave this state quickly.

That being said, wantrepreneurs seem to be a group with great potential for creating new businesses. It is of vital importance to economic policy to answer the key question: What are the measures that increase the probability of transitioning from the state of wantrepreneurship to actually founding a business? Finding these instruments may significantly help increase the number of new firms, increase innovativeness, and, ultimately, create more economic prosperity. Henceforth, we consider wantrepreneurs to be promising field where theories concerning the mechanisms of creating new entrepreneurs can be both formulated and verified.

References

Abraham, C., Sheeran, P.: Acting on intentions: The role of anticipated regret. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 42(4), 495–511 (2003)

Achtziger, A., Gollwitzer, P.M., 2008. Motivation and volition during the course of action. In: Heckhausen, J., Heckhausen, H. (Eds.), Motivation and Action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 272–295.

Adriaanse, M.A., Vinkers, C.D.W., De Ridder, D.T.D., Hox, J.J., De Wit, J.B. F: Do implementation intentions help to eat a healthy diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Appetite 56(1), 183–193 (2011)

Ajzen, I.: From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In: Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J. (eds.) Action control, pp. 11–39. Springer, Berlin (1985)

Ajzen, I.: The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 50(2), 179–211 (1991)

Ajzen, I.: The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 26(9), 1113–1127 (2011)

Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M.: Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs (1980)

Anderson, C.J.: The psychology of doing nothing: Forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychol. Bull. 129, 139–167 (2003)

Anwar, M.N., Daniel, E.: The role of entrepreneur-venture fit in online home-based entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. J. enterprising cult. 24(04), 419–451 (2016)

Arenius, P., Minniti, M.: Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 24, 233–247 (2005)

Armitage, C.J., Conner, M.: Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 40(4), 471–499 (2001)

Bandura, A.: Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice-Hall, Englewood-Cliffs (1986)

Barczyk, C.C., Duncan, D.G.: Social networking media: An approach for the teaching of international business. J. Teach. Int. Bus. 23(2), 98–122 (2012)

Bateman, T.S., Crant, J.M.: The proactive component of organizational behaviour: A measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 14, 103–118 (1993)

Becker, H.S.: ‘Notes on the concept of commitment’. Am. J. Sociol. 66(1), 32–40 (1960)

Bird, B.: Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: the case for intention. Acad. Manag. Rev. 13(3), 442–453 (1988)

Bird, B.: The operations of intentions in time: The emergence of the new venture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 17(1), 11–20 (1992)

Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T. S., Osiyevskyy, O., & Shirokova, G. (2019). When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. Journal of Business Research, 96, 309–321.

Bosma, N., Jones, K., Autio, E., Levie, J.: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2007 Executive Report. London Business School, London (2007)

Burger-Helmchen, T.: Unusual entrepreneurs for unusual entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrepreneurship Innov. 5(3), 241–257 (2020)

Carter, N.M., Gartner, W.B., Reynolds, P.D.: Exploring start-up event sequences. J. Bus. Ventur. 11(3), 151–166 (1996)

CB Insights. (2019). Why Startups Fail: Top 20 Reasons l CB Insights. Retrieved April 28, 2021, from https://www.cbinsights.com/research/startup-failure-reasons-top/

Charmaz, K.: Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage, Thousand Oaks (2006)

Cope, J.: Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 29(4), 373–397 (2005)

Dabić, M., Vlačić, B., Kiessling, T., Caputo, A., Pellegrini, M.: (2021). Serial entrepreneurs: A review of literature and guidance for future research. J. Small Bus. Manag., 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1969657

Davidsson, P.: Ditching discovery-creation for unified venture creation research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 0(00), 1–19 (2021)

Dew, N., Read, S., Sarasvathy, S.D., Wiltbank, R.: Effectual versus predictive logics in entrepreneurial decision-making: Differences between experts and novices. J. Bus. Ventur. 24(4), 287–309 (2009)

Ferrari, F.A.: Theoretical Approach Exploring Knowledge Transmission Across Generations in Family SMEs. In: Mehdi Khosrow-Pour (Eds), Encyclopaedia of Organizational Knowledge, Administration, and Technology, pp. 1531–1550. IGI Global (2020)

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I.: Predicting and changing behaviour: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press, New York (2010)

Frese, M.: Toward a psychology of entrepreneurship: An action theory perspective. Now Publishers Inc. (2009)

Frese, M., Zapf, D.: Action as the core of work psychology: A German approach. Handbook of Ind. Organ. Psychol. 4(2), 271–340 (1994)

Gabrielsson, J., Hägg, G., Landström, H., Politis, D.: Connecting the past with the present: the development of research on pedagogy in entrepreneurial education. Educ. Train. 62(9), 1061–1086 (2020)

Gartner, W.B. (1985) ‘A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 696–706.

Gianiodis, P.T., Meek, W.R.: Entrepreneurial education for the entrepreneurial university: a stakeholder perspective. J. Technol. Transf. 45(4), 1167–1195 (2020)

Gielnik, M.M., Barabas, S., Frese, M., Namatovu-Dawa, R., Scholz, F.A., Metzger, J.R., Walter, T.: A temporal analysis of how entrepreneurial goal intentions, positive fantasies, and action planning affect starting a new venture and when the effects wear off. J. Bus. Ventur. 29(6), 755–772 (2014)

Gielnik, M.M., Frese, M., Kahara-Kawuki, A., Wasswa Katono, I., Kyejjusa, S., Ngoma, M., Oyugi, J.: Action and action-regulation in entrepreneurship: Evaluating a student training for promoting entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 14(1), 69–94 (2015)

Gieure, C., Benavides-Espinosa, M., Roig-Dobón, S.: Entrepreneurial intentions in an international university environment. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 25(8), 1605–1620 (2019)

Gollwitzer, P.M.: (1990). Action phases and mind-sets. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior, 2, 53–92

Gollwitzer, P.M.: Benefits of planning. In: Gollwitzer, P.M., Bargh, J.A. (eds.) The psychology of action: linking cognition and motivation to behaviour, pp. 287–312. Guilford Press, New York (1996)

Gollwitzer, P.M.: Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am. Psychol. 54(7), 493–503 (1999)

Gollwitzer, P.M.: Mindset theory of action phases. In: P.A. Van Lange, Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T. (eds.) Handbook of theories of social psychology, pp. 526–545. Sage, Los Angeles (2012)

Gollwitzer, P.M., Sheeran, P.: Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 69–119 (2006)

González-López, M.J., Pérez-López, M.C., Rodríguez-Ariza, L.: From potential to early nascent entrepreneurship: the role of entrepreneurial competencies. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res.17(3), 1387–1417 (2021)

Gur, F.A., Mathias, B.D.: Finding Self Among Others: Navigating the Tensions Between Personal and Social Identity. Entrep. Theory Pract. 45(6), 1463–1495 (2021)

Hacker, W.: Arbeitspsychologie. Huber, Stuttgart (1986)

Hatala, J.P.: Identifying barriers to self-employment: the development and validation of the barriers to entrepreneurship success tool. Perform. Improv. Q. 18(4), 50–70 (2005)

Holmberg, S. R., & Morgan, K. B. (2003). Franchise turnover and failure: New research and perspectives. Journal of Business Venturing, 54(3), 403–418.

Joensuu-Salo, S., Varamäki, E., Viljamaa, A.: Beyond intentions – What makes a student start a firm? Educ. Train. 57(8/9), 853–873 (2015)

Karoly, P.: Mechanisms of self-regulation: A systems view. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 44(1), 23–52 (1993)

Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., Fink, M.: Robustness of the theory of planned behaviour in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 39(3), 655–674 (2015)

Keh, H.T., Foo, D., M., & Lim, B.C.: Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: The cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 27(2), 125–148 (2002)

Keith, N., Unger, J.M., Rauch, A., Frese, M.: Informal learning and entrepreneurial success: A longitudinal study of deliberate practice among small business owners. Appl. Psychol. 65(3), 515–540 (2016)

Kessler, A., Frank, H.: Nascent entrepreneurship in a longitudinal perspective: The impact of person, environment, resources and the founding process on the decision to start business activities. Int. Small Bus. J. 27(6), 720–742 (2009)

Klingsieck, K. B., Grund, A., Schmid, S., & Fries, S. (2013). Why students procrastinate: A qualitative approach. Journal of College Student Development, 54(4), 397–412.

Klyver, K., Steffens, P., Lomberg, C.: Having your cake and eating it too? A two-stage model of the impact of employment and parallel job search on hybrid nascent entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 35(5), 106042 (2020)

Knott, A.M., Posen, H.E.: Is failure good? Strateg. Manag. J. 26(7), 617–641 (2005)

Kolvereid, L.: Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 21(1), 47–58 (1996)

Kolvereid, L., Isaksen, E.: New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. J. Bus. Ventur. 21(6), 866–885 (2006)

Krueger, N.F., Carsrud, A.L.: Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship Reg. Dev. 5(4), 315–330 (1993)

Krueger, N.F. Jr., Reilly, M.D., Carsrud, A.L.: Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 15(5–6), 411–432 (2000)

Langowitz, N., Minniti, M.: The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrep. Theory Pract. 31, 341–364 (2007)

Liñán, F., Fayolle, A.: A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 11(4), 907–933 (2015)

Locke, E.A., Latham, G.P.: Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation – a 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 57(9), 705–717 (2002)

Loewenstein, G., Lerner, J.: The role of affect in decision making. In: Davidson, R., Scherer, K., Goldsmith, H. (eds.) Handbook of affective science, pp. 619–642. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2003)

Lofrumento, B.: Wantrepreneur to Entrepreneur: What You Really Need to Know to Start Your First Business. CreateSpace Publishing (2015)

McMullen, J.S., Shepherd, D.A.: Entrepreneurial action and the role of un- certainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Acad. Manag. Rev. 31(1), 132–152 (2006)

Mumford, M.D., Schultz, R.A., Van Doorn, J.R.: Performance in planning: processes, requirements, and errors. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5(3), 213–240 (2001)

Neneh, B.N.: From entrepreneurial alertness to entrepreneurial behaviour: the role of trait competitiveness and proactive personality. Pers. Individ. Dif. 138, 273–279 (2019)

Obschonka, M., Silbereisen, R. K., Cantner, U., & Goethner, M. (2015). Entrepreneurial self-identity: Predictors and effects within the theory of planned behavior framework. Journal of Business Psychology, 30(4), 773–794.

Oettingen, G., Mayer, D.: The motivating function of thinking about the future: Expectations versus fantasies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 83(5), 1198 (2002)

Park, S., Martina, R.A., Smolka, K.M.: (2019). Working Passionately Does Not Always Pay Off: The Negative Moderating Role of Passion on the Relationship Between Deliberate Practice and Venture Performance. In: Caputo, A., Pellegrini, M. (eds.) The Anatomy of Entrepreneurial Decisions. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham

Pauwels, P., Matthyssens, P.: The architecture of multiple case study research in international business, pp. 125–143. Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business (2004)

Pruet, M., Shinnar, R., Tonet, B., Llopis, F., Fox, J.: Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 15(6), 571–594 (2009)

Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship edu- cation where the intention to act lies: an investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial be- havior. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(2), 187–204.

Sarasvathy, S.D.: Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Acad. Manage. Rev. 26(2), 243–263 (2001)

Sarasvathy, S.D.: Even-if: Sufficient, yet unnecessary conditions for worldmaking. Organization Theory 2(2), 1–9 (2021)

Schlaegel, C., Koenig, M.: Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: a meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 38(2), 291–332 (2014)

Shane, S., Venkataraman, S.: The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manage. Rev. 25(1), 217–226 (2000)

Shapero, A.: The entrepreneurial event. In: Kent, C.A. (ed.) Environment for entrepreneurship, pp. 21–40. D.C. Heath, Lexington (1984)

Shapero, A., Sokol, L.: Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In: Kent, C., Sexton, D., Vesper, K. (eds.) The encyclopedia of entrepreneurship, pp. 72–90. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs (1982)

Shaqiri, G., Sula, O.: (2015). The role of international networks in establishing a youth innovative entrepreneurial culture in post-communist countries: a comparison between Albania and Estonia. In 9th Annual South-East European Doctoral Student Conference (p. 120)

Sharafizad, J.: Informal learning of women small business owners. Education+ Training (2018)

Shepherd, D.A.: Learning from business failure: propositions of grief recovery for the self-employed. Acad. Manag. Rev. 28, 318–328 (2003)

Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., Bogatyreva, K.: Exploring the intention-behaviour link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Eur. Manag. J. 34(4), 386–399 (2016)

Sinkovics, N.: Pattern matching in qualitative analysis. In: Cassell, C., Cunliffe, A.L., Grandy, G. (eds.) The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods, pp. 468–485. Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks (2018)

Sniehotta, F.F., Schwarzer, R., Scholz, U., Schüz, B.: Action planning and coping planning for long-term lifestyle change: theory and assessment. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 35(4), 565–576 (2005)

Stoianov, N.: (2016). Examining the pathways to business ownership for wantrepreneurs and entrepreneurs (Doctoral dissertation, Saybrook University)

Tkashev, A., Kolvereid, L.: Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrepreneurship Reg. Dev. 11(3), 269–280 (1999)

Trochim, W.M.K.: (1989). Outcome pattern matching and program theory. Eval. Program Plann., 12, 355–366

Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., Fink, M.: From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: Self-control and action-related doubt, fear, and aversion. J. Bus. Ventur. 30(5), 655–673 (2015)

Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., Wincent, J., & Biniari, M. (2018). Implementation intentions in the entrepreneurial process: concept, empirical findings, and research agenda. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 923–941.

Verbruggen, M., & De Vos, A. (2020). When people don’t realize their career desires: Toward a theory of career inaction. Academy of Management Review, 45(2), 376–394.

Yin, R.K.: Case Study Research. Design and Methods. Sage, Thousand Oaks (1984)

Zeelenberg, M., Pieters, R.: A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology 17(1), 3–18 (2007)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackiewicz, M. Why do wantrepreneurs fail to take actions? Moderators of the link between intentions and entrepreneurial actions at the early stage of venturing. Qual Quant 57, 323–344 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01337-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01337-5