Abstract

We consider the possibility of generation steerable states in Bose–Hubbard system composed of three interacting wells in the form of a triangle. We show that although our system still fulfills the monogamy relations, the presence of additional coupling which transforms a chain of wells onto triangle gives a variety of new possibilities for the generation of steerable quantum states. Deriving analytical formulas for the parameters describing steering and bipartite entanglement, we show that interplay between two couplings influences quantum correlations of various types. We compare the time evolution of steering parameters to those describing bipartite entanglement and find the relations between the appearance of maximal entanglement and disappearance of steering effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Quantum steering, although described by Schrödinger long time ago [1], remains one of the most intriguing physical phenomena. As it was quite recently shown, the steering effect, besides its commonly discussed form which is related to the EPR nonlocality [2], has its temporal [3,4,5] and spatiotemporal forms [6]. It should be noted that quantum steering is weaker than Bell-type correlations but stronger than quantum entanglement. That means that steerable quantum states are a subset of the entangled ones, while those exhibiting Bell-type nonlocality are a subset of the steerable states [7]. In general, steerable states can be applied in various branches of quantum information theory (see the special issue [8] and the references quoted therein).

Besides applications of steerable states, it is still interesting to find physical systems which would be suitable candidates for a source of steering effect. It is important to consider not only such systems but also to determine the conditions for the most efficient steerable states generation. Moreover, as we have mentioned above that steering effects are strongly related to quantum entanglement [9], it is important to find the relation between the appearance of those two types of correlations in particular models. Therefore, we shall consider here one of the most promising models in a context of such problems. We concentrate here on a three-mode conventional Bose–Hubbard system. Bose–Hubbard model was proposed in 1963 by Gersch and Knollman [10] to describe bosons with repulsive interactions. It belongs to a group of fundamental physical models which can be applied for description of bosonic atoms trapped in optical lattices [11, 12] and their quantum walk [13].

The effective Hamiltonian describing standard Bose–Hubbard model consists of two parts. The first of them describes tunneling of particles between neighboring sites of lattices, whereas the second one represents an interaction between bosons located at the same well. What is worth noting, such kind of Hamiltonian also describes models of quantum nonlinear scissors [14,15,16] which involve Kerr-like nonlinear oscillators. Quantum scissors systems can lead to the generation of the states defined in finite-dimensional Hilbert space—we observe there photon (or phonon) blockade effect [17,18,19,20,21,22]. Moreover, various types of quantum correlations, including quantum entanglement, can appear in such models, [23,24,25,26]. Since the effective Hamiltonian describing Bose–Hubbard model involves Kerr-type terms, it can be applied for description of different physical situations. Examples of them can be: quantum dot systems [27], Bose-Einstein condensates [28], photonic crystals [29], micro-cavities with moving mirrors [21, 30, 31] or micro-cavities with current QED systems [32, 33] (at this point, one can mention Santa Barbara experiment [34]). It is also worth noting that such nonlinear systems are very often discussed in a context of quantum chaos theory (for instance see [35,36,37,38]).

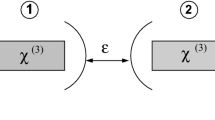

In our paper, we consider the model which is an extension of that proposed by Olsen [39, 40]. The model consists of three potential wells trapping bosonic particles and is modeled by three nonlinear Kerr-type oscillators. We assume here that all pairs of subsystems (wells) interact each other. In consequence, the system has triangle geometry, contrary to the linear chains considered in [39, 40]. We show that additional coupling which transforms the geometry of the model from the linear one to that of triangle form considerably changes the systems’ ability to produce quantum steering effects. The system can be a physical realization of the ideas discussed in our previous paper [9]. We discuss here what kind of the states can be achieved during the system’s evolution, and consider the interplay between the possibility of the appearance of entanglement and steering generation. The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we present our model and present analytical solutions for the probability amplitudes describing time evolution of the system. In Sect. 3, applying steering parameter based on Cavalcanti criterion [41], we discuss time evolution of the steering for two cases. One of them corresponds to symmetric initial conditions, whereas the second to asymmetric ones. Next, analyzing the time evolution of the both: steering parameters and the concurrence, we discuss the relationships between the generation of steerable and entangled states. Finally, in Sect. 4 we present our conclusions.

2 The model

We discuss here the model of a single-mode Bose–Hubbard system containing three potential wells (labeled by 1, 2 and 3). They are coupled each other by linear interaction which can lead to the tunneling of atoms between nearest wells (Fig. 1). Three-well system can be described by the following effective Hamiltonian:

where

describes three potential wells. Each well is represented by a quantum, Kerr-type nonlinear oscillator described by nonlinearity constant \(\chi \) which is related to the collisions. The interactions among wells are governed by the Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}_i\):

where pairs of indices ij label two interacting wells (1–2, 2–3, 1–3). The operators \(\hat{a}_{i}\), \(\hat{a}_{i}^{\dagger }\) appearing here are usual boson annihilation and creation operators, respectively (corresponding to the well i). The parameters describe the strength of couplings between two wells \(i-j\), where \(\varepsilon _{ij}=\varepsilon _{ij}^{*}\).

Here, we are interested in a possibility of generation steerable and entangled states. We assume here that the interactions among the wells are weak, analogously to the models of quantum scissors discussed in [26, 42], i.e., \(\varepsilon _{12}=\varepsilon _{23}=\varepsilon _{13}=0.001\chi \). Moreover, to check the influence of the coupling strength on the properties of generated states we assume here that two coupling parameters are equal each other (\(\varepsilon _{12}=\varepsilon _{23}=\varepsilon \)), whereas the third parameter \(\varepsilon _{13}\) vary from 0 to \(4\varepsilon \).

For the situation discussed here, we will concentrate on the two cases. For the first of them, only the second well is occupied at the initial time, and then, the wave function describing the system can be written as \(\vert \psi (t=0)\rangle =\vert 0\rangle _1\otimes \vert 1\rangle _2\otimes \vert 0\rangle _3=\vert 010\rangle \). This case we will be referred to as “symmetric.” For the second situation, the evolution of our system starts from the state \(\vert \psi (t=0)\rangle =\vert 1\rangle _1\otimes \vert 0\rangle _2\otimes \vert 0\rangle _3=\vert 100\rangle \), when initially only first well is occupied—we are dealing here with the “asymmetric” case. As we assumed that our system does not interact with any external one, the system’s evolution remains closed within the set of three states (\(\vert 0 0 1\rangle \), \(\vert 0 1 0\rangle \), \(\vert 1 0 0\rangle \)), and hence, the system can be treated as three-qubit one. Thus, the system can be described by the following wave function:

where \(C_{001}\), \(C_{001}\) and \(C_{001}\) are complex probability amplitudes corresponding to the states \( \vert 001\rangle \), \(\vert 001\rangle \) and \(\vert 100\rangle \), respectively.

Next, applying the procedure described in [42], we find solutions for those amplitudes. For the symmetric case, when the system’s time evolution starts from the state \(\vert \psi (t=0)\rangle =\vert 0 1 0\rangle \), we get

where appearing here frequency \(\omega \) is defined as:

Analogously, for the asymmetric case, when the initial system’s state is \(\vert \psi (t=0)\rangle =\vert 1 0 0\rangle \), we have the following solution which takes more than previously complicated form:

We see that for the both cases, the frequencies of oscillations of probability amplitudes depend on the both coupling parameters: \(\varepsilon \) and \(\varepsilon _{13}\).

3 Steering and entanglement

This section is devoted to the quantum properties of coupled three potential wells, particularly to the steering and entanglement properties of the system. We will analyze bipartite steering and entanglement between two considered wells applying Cavalcanti’s steering parameter and the concurrence. Such two classes of quantum correlations were very extensively studied in last years. They were considered in discussions of various physical systems. For example, there were three-mode optomechanical system composed of an atomic ensemble located in a cavity comprising oscillating mirror [43], double-cavity optomechanical model with two separate electromagnetic fields mediated by a mechanical oscillator [44] or optical cavity field and the mechanical oscillator system [45].

As a parameter describing the presence and strength of steering between two wells i and j, we apply here steering parameter \(S_{ij}\) defined with use of inequality defined by Cavalcanti et al. [41]. Such parameter can be expressed as

where i, j label the wells. When steering parameter \(S_{ij}\) takes values greater than zero, the mode j steers the mode i. The steering in opposite direction appears when \(S_{ji}\) becomes positive. Hence, we can observe two types of steering—the symmetric (SS) and asymmetric (AS) ones. SS appears when at the same time the both parameters \(S_{ij}\) and \(S_{ji}\) are greater than zero. If only one them (\(S_{ij}\) or \(S_{ji}\)) is positive, the steering is asymmetric.

Since we are dealing here with qubit systems, we apply the concurrence introduced by Hill and Wootters [46, 47], as a good measure of bipartite entanglement—for our case, the entanglement between two wells. The concurrence of two-qubit state described by the density matrix \(\rho _{ij}\) can be calculated from the formula

The parameters \(\lambda _{l}\) appearing above are the eigenvalues of matrix R derived from the relation \(R=\rho _{ij}\tilde{\rho _{ij}}\), where \(\tilde{\rho _{ij}}\) is defined as \(\tilde{\rho _{ij}}=\sigma _{y}\otimes \sigma _{y}\rho _{ij}^{*}\sigma _{y}\otimes \sigma _{y}\) and \(\sigma _{y}\) is \(2\times 2\) Pauli matrix. The density matrix \(\rho _{ij}\) describing two-subsystem state can be obtained by tracing out the third one \(\rho _{ij}=Tr_{k}(\rho _{ijk})\). The concurrence takes values between 0 for product states and the unity for maximally entangled two-qubit states.

3.1 Symmetric case

We start our study of bipartite steering and entanglement from the case when only the second well is initially occupied, and thus, the evolution of considered system starts from the state \(\vert \psi (t=0)\rangle =\vert 0 1 0\rangle \). Such situation we refer to as symmetric case—the fact of symmetry/asymmetry concerns initial population of the system, not the parameters or discussed system’s geometry. Thus, applying formulas (5, 8) we can express the steering parameters as:

where \(\omega \) was already defined in (6). From these solutions, one can see that the steering parameters depend on the both coupling parameters \(\varepsilon \) and \(\varepsilon _{13}\).

First, we concentrate on the situation when all couplings are of identical strength (\(\varepsilon =\varepsilon _{13}\)). For such a case, eqs. (10) reduce to following form

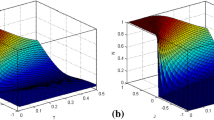

Thus, one can see that only parameters \(S_{12}\) and \(S_{32}\) take values greater than zero, whereas the remaining parameters are always non-positive. That means that the steering appearing in the system is asymmetric. Moreover, when we observe steering, the subsystem 2 steers simultaneously two subsystems: 1 and 3. Additionally, two subsystems cannot steer third one at the same time, and this fact agrees with the monogamy relation [48]. From (11), we see that steering parameters \(S_{12}\) and \(S_{32}\) change periodically with the period \(T=\frac{2\pi }{3\varepsilon }\), whereas the steering parameters take their maximal values for the moments of time \(t\approx 0.18T+nT\) and \(t\approx 0.82T+nT\) (\(n=0,1,2\ldots \))—see Fig. 2. When steering parameters reach their maximal values, the probability corresponding to the state \(\vert 010\rangle \) fulfills the relation \(\vert C_{010}\vert ^2=0.75\).

Next, we check the system’s ability to produce entanglement. Applying relations (5) and (9), we can obtain the formulas describing concurrence for all pairs of subsystems. We express them as:

We see that all three parameters change their values periodically with the same periods as those for the steering parameters. The maximal value of the concurrences \(C_{12}=C_{23}\) is equal to \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\), and the strongest bipartite entanglement for the pairs 1–2 and 2–3 appear for the moments of time when \(t\approx 0.27T+nT\) and \(t\approx 0.73T+nT\) (\(n=0,1,2\ldots \)) (see Fig. 2a). What is interesting, the strongest entanglement and steering are not generated simultaneously. Additionally, maximal degree of the entanglement for subsystems 1 and 3 is greater than that for subsystems 1–2 and 2–3 (Fig. 2b). Despite that fact, we cannot observe steering between those subsystems. The concurrences \(C_{12}\) and \(C_{23}\) reach their maximal values when the probability \(\vert C_{010}\vert ^2= 0.5\)

From (10), we see that if \(\varepsilon \ne \varepsilon _{13}\) , only parameters \(S_{12}\) and \(S_{32}\) take their values greater than zero, analogously as in previous case. Additionally, two modes cannot steer third mode at the same time in accordance with monogamy results of Reid [48]. Therefore, for symmetric case the parameters \(S_{21}\) and \(S_{23}\) never are positive, and hence, subsystems 1 and 3 cannot steer subsystem 2 together. Furthermore, \(S_{13}\) and \(S_{31}\) are non-positive, as well. In consequence, we cannot observe symmetric steering in the model. Only parameters \(S_{12}\) and \(S_{32}\) can take positive values, and only subsystem 2 can steer those labeled 1 and 3 simultaneously—the steering for other pairs and directions can not be observed.

Time evolution of the steering parameters \(S_{ij}\)—(a), and maximal values of \(S_{ij}\) as a function of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \)—(b), for the symmetric case. Time is measured in units of T, where T is period of the evolution when \(\varepsilon =\varepsilon _{13}=0.001\chi \). For a, left figure presents some exemplary plots for chosen values of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \), whereas on the right the map for continuously varied values of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \) is presented

Figure 3a depicts time evolution of steering parameters \(S_{ij}\) for various values of the ratio \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \). White area shown in the diagram (right) corresponds to the situation when \(S_{ij}\le 0\)—subsystem j does not steer subsystem i. The gray area represents cases when steering effect appears—\(S_{ij}> 0\). From the figure, we see that for different values of the coupling constant subsystems 1 and 3 can be steered simultaneously by 2, and we see from our solutions and Fig. 3b that steering corresponding to other pairs of subsystems cannot observed. When the strength of the interaction between the wells 1 and 3 increases, the frequency of oscillations of \(S_{12}\) and \(S_{32}\) becomes greater and greater. However, the oscillations always remain regular. For \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon >2.83\), steerable states are generated (almost) permanently, and only oscillatory changes of the degree of steerability are present.

From Fig. 3b, we see that only \(S_{12}\) and \(S_{32}\) can reach positive values. Moreover, for arbitrary coupling constant \(\varepsilon _{13}\) their maximal values remain unchanged. It should be emphasized that symmetric system can produce very stable steering effect—changes of coupling strengths when \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon >2.83\) do not lead to the disappearing of the steerability \(2\rightarrow 3\) and \(2\rightarrow 1\) (notation \(i\rightarrow j\) means that subsystem i steers j). Additionally, the same as for the case when all three coupling strengths were identical, for the situation presented here, steering parameters reach their maximal values when \(\vert C_{010}\vert ^2=0.75\).

The same as in Fig. 3 but for the concurrences \(C_{ij}\) instead of the steering parameters \(S_{ij}\)

Analogously to the previous cases, Fig. 4a depicts time evolution of the concurrences \(C_{ij}\), whereas Fig. 4b shows maximal values of them for various strengths of the interactions. To determine those parameters, we derived the formulas describing their time evolution. They can be written as:

In Fig. 4a (left), we present results for some exemplary values of the ratio \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \), whereas in Fig. 4a (right) maps exhibiting time dependence of the concurrence for the whole considered here range of values of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \) are shown. Thus, white areas shown in maps correspond to the situations when the concurrence \(C_{ij}= 0\), i.e., bipartite entanglement does not appear there—we are dealing there with product states defined in a given subspace corresponding to two wells. The gray regions denotes the situations when \(C_{ij}> 0\). From this figure and equations (13), we see that for all pairs of subsystems entangled state are generated. The value of concurrence changes periodically with the period \(T={\pi }/{\omega }\). For the pairs 1–2 and 2–3, the maximal degree of entanglement is smaller than the degree of its counterpart corresponding to the wells 1 and 3 (see Fig. 4a). From Fig. 4b, one can see that the maximal value of the concurrency \(C_{12}=C_{23}\) practically does not depend on the value of \(\varepsilon _{12}\) when \(\varepsilon _{13}\lesssim 2.83\varepsilon \), and we have \(C_{12}^{\max }=C_{23}=0.7071\). Then, when the coupling strength \(\varepsilon \) increases, such maximal value starts falling down. Such changes of maximal values of the concurrency are accompanied by simultaneous appearance of the permanent steering within subsystems 1–2 and 2–3. What is interesting, the maximal amount of entanglement within those subsystems is created when corresponding to them steering does not attain its maximum. From other side, for the subsystem 1–3, for which steering effect does not appear, the concurrence describing bipartite entanglement varies from 0.33 to 0.99 with changes of the coupling strength \(\varepsilon _{13}\) from 0 to 4. We see that the strongest entanglement is present when \(\varepsilon _{13}\) is close to zero. For such a case, considered triangle system becomes a chain-like one, and our system produces almost maximally entangled bipartite state. The same as previously, when \(\varepsilon _{13}=\varepsilon \) was assumed, here for \(\varepsilon _{13}<2.83\varepsilon \) the concurrence reaches its maximal value when the relation \(\vert C_{010}\vert ^2= 0.5\) is fulfilled. From other side, when \(\varepsilon _{13}\ge 2.83\varepsilon \) and the concurrence is maximal, the probability \(P_{010}=\vert C_{010}\vert ^2\) is greater than 0.5.

To clarify the relations and mutual interplay between the entanglement and steering generated in our system, we show in Fig. 5 the “trajectory” of the states which are produced during the system’s evolution. Each point of the ”trajectory” corresponds to one state characterized by a given value of concurrence \(C_{12}=C_{32}\) and corresponding to it steering parameter \(S_{12}=S_{32}\). One should remember that for all cases considered here we do not observe steering effect for the pair \(1\leftrightarrow 2\), and therefore, we plot the “trajectory” only for the mentioned above parameters. What is worth noting, all states which can be generated for the “symmetric” case are located at the line shown in Fig. 5.

From Fig. 5, one can see that for the case discussed here, maximally entangled states never will be generated—maximal value of \(C_{12}=C_{32}\) is \(\sim 0.7\). Moreover, at that point, we have a border between steerable and unsteerable states. For remaining points of our “trajectory” to the one value of concurrency correspond two states—only one of them is steerable. Maximal steering can be achieved by the states which are characterized by \(C_{12}=C_{32}\simeq 0.6\), whereas for the maximal value of the concurrence steering parameter \(S_{12}\rightarrow 0\).

3.2 Asymmetric case

At this point, we consider “asymmetric” case, when our system’s evolution starts from the state \(\vert \psi (t=0)\rangle =\vert 1 0 0\rangle \). Such situation we call “asymmetric”, as we have the asymmetric population of the system’s initial state—only the first well is initially occupied (see Fig. 1). For such a case, steering parameters can be found in the following form:

where

and the frequency \(\omega \) appearing here is the same as that defined by (6) in the section devoted to the description of our model.

From (14) and Fig. 6, we see that the character of process of steering generation depends on the value of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \). For instance, for every value of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \) we can observe that initially occupied subsystem 1 steers subsystems 2 and 3 (\(S_{21}>0\) and \(S_{31}>0\)) for a some period of time starting from \(t=0\) (see Fig. 6a). Such behavior corresponds to the results obtained for the “symmetric” case considered in previous subsection. Moreover, for \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon =1\) the parameters \(S_{23}\) and \(S_{13}\) are non-positive, and hence, we see that subsystem 3 never steers 1 and 2. However, if \({\varepsilon _{13}}/{\varepsilon }\ne 1\) such steering effects (\(3\rightarrow 2\) and \(3\rightarrow 1\)) can appear for some periods of time. We observe sudden vanishing of the steering and its sudden restoring—it resembles phenomena of sudden death of entanglement [49, 50] and it sudden rebirth [51, 52]. What is interesting, steering for two pairs of subsystems \(2\rightarrow 1\) and \(2\rightarrow 3\) never can be achieved (see Fig. 6b).

Moreover, it is seen that steering in two pairs of subsystems \(1\rightarrow 3\) and \(3\rightarrow 1\) does not appear simultaneously. One can say that in general, for the model discussed here, only asymmetric steering can be generated—symmetric one cannot be achieved. Moreover, from Fig. 6a we see that at the same time two subsystems/wells cannot steer the third one, while one of them can steer two other subsystems/wells, what is in agreement with the monogamy results of Reid [48] and we see that the subsystem 1 can steer those labeled by 2 and 3 and additionally 3 steers 1 and 2. It should be emphasized that although wells 1 and 3 can steer that denoted by 2, the monogamy relation is not violated because such steering corresponding to pairs of wells appears at different moments of time.

From Fig. 6b, we see that the steering parameters can rapidly change its values with changes of \(\varepsilon _{13}\). In such sense, we can treat the system for “asymmetric case” as unstable. Even small changes of \(\varepsilon _{13}\) can lead to the significant increase in \(S_{ij}\), and in some cases even steering disappearance. Especially, when \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \) becomes close to unity, steering effects for the pairs of wells \(3\rightarrow 1\) and \(3\rightarrow 2\) disappear (however, for two other pairs steerability effects remains). From other side, when the parameter \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \) becomes significantly large, the situation stabilizes and we do not observe such sudden decreasing value of \(S_{ij}\). This case corresponds to the situation when the second well is only slightly coupled to the remaining two neglected, and its influence can be neglected. Thus, we see that to obtain a stable steering effect it is better to apply the situation described in previous subsection “symmetric” case. By contrast, for the “asymmetric” case we can observe other types of the steerability than previously.

Time evolution of the concurrence \(C_{ij}\) for “asymmetric” case and some exemplary values of \(\varepsilon _{13}\) (a), and maximal values of \(C_{ij}\) (\(\{i,j\}=\{1,2,3\}\)) for \(0\le (\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon )\le 4\) (b). Definition of time T and values of other parameters are the same as for previous figure

The same as previously, we can derive the formulas determining concurrence for three pairs of subsystems (pairs of wells which can be treated as qubits). They can be expressed as

where \(A_3=4\varepsilon ^2+\varepsilon _{13}^2\).

In Fig. 7a, we see time evolution of \(C_{ij}\) (\(\{i,j\}=\{1,2,3\}\)) for exemplary values of \(\frac{\varepsilon _{13}}{\varepsilon }\). As previously, the values of all concurrences depend on coupling parameters \(\varepsilon \) and \(\varepsilon _{13}\), but here we have eight effective frequencies. In consequence, various beating effects among them appear, which defaces clear picture of the evolution. Despite it, one can see that bipartite entanglement between all pairs of subsystems i and j can be generated. Moreover, for some moments of time and for some particular values of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \) two-qubit states can be very close to the maximally entangled states. In particular, for pairs 1–2 and 2–3 the maximal values of concurrence can be \(\sim \)0.7071 to \(\sim \)0.9186. Moreover, we see that maximal values of concurrence strongly depend on \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \). Especially, \(C_{13}\) can rapidly change its value when the strength of interaction is modified, but for larger values of \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \) (the interaction between wells 1 and 3 becomes dominant) it stabilizes and becomes close to unity. One can explain such behavior as a result of the fact that the probabilities \(P_{001}\) and \(P_{100}\) tend to one half, whereas probability for state \(\vert 010\rangle \) tends to zero. In consequence, we deal here with a state which becomes close to maximally entangled state (Bell-like state) spanned in subspaces corresponding to the wells 1 and 3. Obviously, for such cases remaining two parameters (\(C_{12}\) and \(C_{23}\)) decrease, so bipartite entanglement present in the system concentrates in subsystem 1–3.

When \(\varepsilon _{13}/\varepsilon \simeq 1\), similarly as for the steering parameters, we observe distinct minima for \(C_{13}\) and \(C_{12}\) describing the entanglement for the qubits involving initially populated well 1—such behavior is not well pronounced for \(C_{23}\). What is interesting for such a case all parameters \(S_{ij}\) also decrease considerably and become non-positive, except \(S_{21}\) and \(S_{31}\) so, only subsystem 1 steers two other.

To compare the dynamics of the entanglement and steering for the case considered here, we plotted the “trajectories” of the states which are produced by ‘asymmetric” system, analogously as in the previous subsection. They are presented in Fig. 8.

We see that instead of a single line which appeared for the “symmetric” case, here we have the regions corresponding to the appearance (or nonappearance) of steering effect. In consequence, for a given value of the concurrence, we have an infinite number of states from which only some of them are steerable. It is seen that we will never achieve maximally entangled states for the pairs \(1\leftrightarrow 2\) and \(2\leftrightarrow 3\)—the maximal value of the concurrence is slightly greater than 0.9. However, contrary to the “symmetric” case, for such situation steerable states are produced. Moreover, maximal steering can be generated when the concurrence \(\sim 0.83\). It should be noted that when we observe steering effects for the pair \(1\leftrightarrow 2\), such effects are not present for \(2\leftrightarrow 3\), and vice versa. In Fig. 8, we plot only the values of \(S_{21}\) and \(S_{23}\). The parameters \(S_{12}\) and \(S_{32}\) are always negative, so we do not observe steering effects corresponding to them. Moreover, as one can see from the previous figures, the steering corresponding to the pairs \(1\leftrightarrow 2\) and \(2\leftrightarrow 3\) is asymmetric—if it appears for a given pair of subsystems, it acts only in one direction. As shown in Fig. 6, when \(S_{21}\) is positive, \(S_{23}\) is negative and vice versa. Thus, our “phase diagram” only shows the ability to produce steering for a given pair and in a particular direction.

For the pair \(1\leftrightarrow 3\), we observe the entirely different situation. Maximally entangled states can appear in the system, and, analogously as for the “symmetric” case discussed in the previous subsection, for such a case the states are not steerable. Nevertheless, we can find maximal steering effects when entanglement is quite strong, i.e., when \(C_{13}\simeq 0.86\). Moreover, analogously to the situation mentioned above and corresponding to the pairs \(1\leftrightarrow 2\) and \(2\leftrightarrow 3\), only asymmetric steering can appear in the system. If steering is observed in the direction \(1\rightarrow 3\) (\(3\rightarrow 1\)), it is not present for \(3 \rightarrow 1\) (\(1\rightarrow 3\)) (see Fig. 6).

4 Summary

We discussed here the Bose–Hubbard system containing three potential wells. The wells were coupled each other such a way that the system was in a triangle configuration. We assumed that only one well was initially occupied, and the total number of particles was preserved. Our model can be treated as a three-qubit system.

We analyzed two situations—two different initial states of the system (“symmetric” and “asymmetric” cases). We were interested in the time evolution of quantum correlations appearing in the system. In particular, we have shown that such system can be a source of the two-qubit steering and entanglement effects. Deriving analytical formulas, we also showed that the degree of the both: steering and quantum entanglement, strongly depends on the relation between strengths of the coupling between wells. However, for the “symmetric” case we did not observe such dependence in the steering’s dynamics. Comparing “symmetric” and “asymmetric” cases, we proved that for the latter situation, two additional steerabilities could appear in the system. Moreover, for the “asymmetric” case, subsystem labeled by 3 can steer two others – such form of steering did not appear for the “symmetric” case.

From the other side, for all situations considered here, only asymmetric steering can be generated. Moreover, when steering effects are present in the system, one qubit steers remaining two, whereas two qubits cannot steer the remaining one simultaneously.

Additionally, the steering parameter and concurrence reach their maximal values for different strengths of the couplings. What is interesting, for all cases discussed here, when two wells become maximally entangled, the steering effects for such pair disappear.

References

Schrödinger, E.: Discussion of probability relations between separated systems. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 31, 555 (1935)

Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., Rosen, N.: Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev. 47, 777 (1935)

Chen, Y.-N., Li, C.-M., Lambert, N., Chen, S.-L., Ota, Y., Chen, G.-Y., Nori, F.: Temporal steering inequality. Phys. Rev. A 89, 032112 (2014)

Bartkiewicz, K., Černoch, A., Lemr, K., Miranowicz, A., Nori, F.: Temporal steering and security of quantum key distribution with mutually unbiased bases against individual attacks. Phys. Rev. A 93, 062345 (2016)

Bartkiewicz, K., Černoch, A., Lemr, K., Miranowicz, A., Nori, F.: Experimental temporal quantum steering. Sci. Rep. 6, 38076 (2016)

Chen, S.-L., Lambert, N., Li, C.-M., Chen, G.-Y., Chen, Y.-N., Miranowicz, A., Nori, F.: Spatio-temporal steering for testing nonclassical correlations in quantum networks. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 3728 (2017)

Wiseman, H.M., Jones, S.J., Doherty, A.C.: Steering, entanglement, nonlocality, and the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 140402 (2007)

The special issue of J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 80 years of steering and the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 32, A1–A91 (2015)

Kalaga, J.K., Leoński, W.: Quantum steering borders in three-qubit systems. Quantum Inf. Process. 16(7), 175 (2017)

Gersch, H.A., Knollman, G.C.: Quantum cell model for bosons. Phys. Rev. 129, 959–967 (1963)

Kühner, T.D., Monien, H.: Phases of the one-dimensional bose-hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 58, R14741–R14744 (1998)

Jaksch, D., Bruder, C., Cirac, J.I., Gardiner, C.W., Zoller, P.: Cold bosonic atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3108–3111 (1998)

Preiss, P.M., Ma, R., Tai, M.E., Lukin, A., Rispoli, M., Zupancic, P., Lahni, Y., Islam, R., Greiner, M.: Strongly correlated quantum walks in optical lattices. Science 347, 1229–1233 (2015)

Leoński, W., Tanaś, R.: Possibility of producing the one-photon state in a kicked cavity with a nonlinear Kerr medium. Phys. Rev. A 49, R20–R23 (1994)

Said, R.S., Wahiddin, M.R.B., Umarov, B.A.: Squeezing in multi-mode nonlinear optical state truncation. Phys. Lett. A 365, 380 (2007)

Leoński, W., Kowalewska-Kudłaszyk, A.: Quantum cissors—finite-dimensional states engineering. In: Wolf, E. (ed) Progress in Optics, vol. 56, pp. 131–185. Elsevier (2011)

Özdemir, Ş.K., Miranowicz, A., Koashi, M., Imoto, N.: Quantum-scissors device for optical state truncation: a proposal for practical realization. Phys. Rev. A 64, 063818 (2001)

Özdemir, Ş.K., Miranowicz, A., Koashi, M., Imoto, N.: Pulse-mode quantum projection synthesis: effects of mode mismatch on optical state truncation and preparation. Phys. Rev. A 66, 053809 (2002)

Miranowicz, A., Paprzycka, M., Liu, Y.X., Bajer, J., Nori, F.: Two-photon and three-photon blockades in driven nonlinear systems. Phys. Rev. A 87, 023809 (2013)

Liu, Y.X., Xu, X.W., Miranowicz, A., Nori, F.: From blockade to transparency: controllable photon transmission through a circuit-qed system. Phys. Rev. A 89, 043818 (2014)

Miranowicz, A., Bajer, J., Paprzycka, M., Liu, Y.X., Zagoskin, A.M., Nori, F.: State-dependent photon blockade via quantum-reservoir engineering. Phys. Rev. A 90, 033831 (2014)

Bretheau, I., Campagne-Ibercq, P., Flurin, E., Mallet, F., Huard, B.: Quantum dynamics of an electromagnetic mode that cannot contain N photons. Science 348, 776 (2015)

Said, R.S., Wahiddin, M.R.B., Umarov, B.A.: Generation of three-qubit entangled W state by nonlinear optical state truncation. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 39, 1269–1274 (2006)

Kowalewska-Kudłaszyk, A., Leoński, W., Peřina Jr., J.: Photon-number entangled states generated in Kerr media with optical parametric pumping. Phys. Rev. A 83, 052326 (2011)

Kowalewska-Kudłaszyk, A., Leoński, W., Peřina Jr., J.: Generalized Bell states generation in a parametrically excited nonlinear coupler. Phys. Scripta 2012(T147), 014016 (2012)

Kalaga, J.K., Kowalewska-Kudłaszyk, A., Leoński, W., Barasiński, A.: Quantum correlations and entanglement in a model comprised of a short chain of nonlinear oscillators. Phys. Rev. A 94, 032304 (2016)

Miranowicz, A., Özdemir, Ş.K., Liu, Y.X., Koashi, M., Imoto, N., Hirayama, Y.: Generation of maximum spin entanglement induced by a cavity field in quantum-dot systems. Phys. Rev. A 65, 062321 (2002)

Peřinová, V., Lukš, A., Křapelka, J.: Dynamics of nonclassical properties of two- and four-mode Bose–Einstein condensates. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 46, 195301 (2013)

Greentree, A.D., Tahan, C., Cole, J.H., Hollenberg, L.C.L.: Quantum phase transitions of light. Nat Phys 2(12), 856–861 (2006)

Bose, S., Jacobs, K., Knight, P.L.: Preparation of nonclassical states in cavities with a moving mirror. Phys. Rev. A 56, 4175–4186 (1997)

Wang, H., Gu, X., Liu, Y.X., Miranowicz, A., Nori, F.: Tunable photon blockade in a hybrid system consisting of an optomechanical device coupled to a two-level system. Phys. Rev. A 92, 033806 (2015)

Didier, N., Pugnetti, S., Blanter, Y.M., Fazio, R.: Detecting phonon blockade with photons. Phys. Rev. B 84, 054503 (2011)

Liu, Y.X., Miranowicz, A., Gao, Y.B., Bajer, J., Sun, C.P., Nori, F.: Qubit-induced phonon blockade as a signature of quantum behavior in nanomechanical resonators. Phys. Rev. A 82, 032101 (2010)

O’Connell, A.D., Hofheinz, M., Ansmann, M., Bialczak, R.C., Lenander, M., Lucero, E., Neeley, M., Sank, D., Wang, H., Weides, M., Wenner, J., Martinis, J.M., Cleland, A.N.: Quantum ground state and single-phonon control of a mechanical resonator. Nature 464(7289), 697–703 (2010)

Milburn, G.J., Holmes, C.A.: Dissipative quantum and classical liouville mechanics of the anharmonic oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 2237 (1986)

Milburn, G.J.: Quantum and classical liouville dynamics of the anharmonic oscillator. Phys. Rev. A 33, 674–685 (1986)

Milburn, G.J., Holmes, C.A.: Quantum coherence and classical chaos in a pulsed parametric oscillator with a kerr nonlinearity. Phys. Rev. A 44(7), 4704–4711 (1991)

Leoński, W.: Quantum and classical dynamics for a pulsed nonlinear oscillator. Phys. A 233, 365–378 (1996)

Olsen, M.K.: Spreading of entanglement and steering along small Bose–Hubbard chains. Phys. Rev. A 92, 033627 (2015)

Olsen, M.K.: Asymmetric steering in coherent transport of atomic population with a three-well Bose–Hubbard model. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 32, A15–A19 (2015)

Cavalcanti, E.G., He, Q.Y., Reid, M.D., Wiseman, H.M.: Unified criteria for multipartite quantum nonlocality. Phys. Rev. A 84, 032115 (2011)

Miranowicz, A., Leoński, W.: Two-mode optical state truncation and generation of maximally entangled states in pumped nonlinear couplers. J. Opt. B 39, 1683 (2006)

He, Q., Ficek, Z.: Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox and quantum steering in a three-mode optomechanical system. Phys. Rev. A 89, 022332 (2014)

Tan, H., Zhang, X., Li, G.: Steady-state one-way Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen steering in optomechanical interfaces. Phys. Rev. A 91, 032121 (2015)

Kiesewetter, S., He, Q.Y., Drummond, P.D., Reid, M.D.: Scalable quantum simulation of pulsed entanglement and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen steering in optomechanics. Phys. Rev. A 90, 043805 (2014)

Hill, S., Wootters, W.K.: Entanglement of a pair of quantum bits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 5022–5025 (1997)

Wootters, W.K.: Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2245 (1998)

Reid, M.D.: Monogamy inequalities for the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox and quantum steering. Phys. Rev. A 88, 062108 (2013)

Życzkowski, K., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M., Horodecki, R.: Dynamics of quantum entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 65, 012101 (2001)

Yu, T., Eberly, J.H.: Finite-time disentanglement via spontaneous emission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 140404 (2004)

Ficek, Z., Tanaś, R.: Dark periods and revivals of entanglement in a two-qubit system. Phys. Rev. A 74, 024304 (2006)

Ficek, Z., Tanaś, R.: Delayed sudden birth of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 77, 054301 (2008)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalaga, J.K., Leoński, W. & Szczȩśniak, R. Quantum steering and entanglement in three-mode triangle Bose–Hubbard system. Quantum Inf Process 16, 265 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-017-1717-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-017-1717-5