Abstract

We investigate the relationship between successful revolutions and corruption using data on revolutionary campaigns since 1900 and corruption measures retrieved from the Varieties of Democracy database. We find that successful nonviolent and violent revolutions produce null effects on corruption; education decreases corruption; and upon adjusting for the moderating effect of education, violent revolutions induce corruption. Our results imply that classic narratives celebrating such upheavals as corruption-limiting are oversimplified and optimistic. Our analysis challenges conventional wisdom and contributes an instructive, empirically-grounded assessment of the revolution’s corruption consequences to the scholarship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 1990, The Toronto Star quoted Rebel General Idriss Deby saying, “The MPS (Popular Salvation Movement) will see to it that Chad becomes a democratic country... I’m going to bring changes. We will take our responsibilities.”Footnote 1 Deby’s coup removed one of the most corrupt leaders in the twentieth century, President Hissene Habre of Chad. Despite high hopes from rebels, Idriss Deby siphoned millions in oil revenue and was accused of a series of human rights abuses. Mild reforms were introduced, but Chad experienced higher levels of corruption under Deby’s rule than the prior administration.Footnote 2 We empirically examine the relationship between revolutions, like the one in Chad, and corruption. We test three possible outcomes, including revolutions increasing corruption, remaining constant, and mitigating corruption. We examine both nonviolent and violent revolutions.

Previous research generally defines corruption as an unlawful or unauthorized transfer of money or some substitute (Rose-Ackerman, 1975). More recent research uses the definition “the abuse of public power for private gain” based on the World Bank’s data on corruption (Kapur, 1998). However, these definitions are not consistently applied in the literature, and researchers use a variety of measurements to gauge corruption. The economic literature delineates three prerequisites for corruption (Aidt, 2003). First, there is a need for discretionary power, where leaders must be granted the authority to create policies and regulations. Second, the existence of economic rents, which empower rulers to extract financial resources from businesses or individuals. Lastly, weak institutions within governance systems, as they fail to provide adequate counter-incentives to prevent rent extraction and impede optimal resource allocation.

The causes of corruption are complex, but research has identified some key contributing factors. High economic rents and protectionism foster corruption by enabling corrupt behavior without accountability (Ades & Di Tella, 1999). In developing countries, perceived market failures and principle agent problems are associated with corruption as people exploit positions for personal gain (Banerjee, 1997; Hugo et al., 2023). Fiscal centralization (Fisman & Gatti, 2002), high power distance (Kaasa & Andriani, 2022), corporate culture (Liu, 2016), national culture (Barr & Serra, 2010), foreign aid (Pavlik & Young, 2022), regulatory barriers (Holcombe & Boudreaux, 2015), and low levels of economic freedom (Apergis et al., 2012; Faria et al., 2012) are associated with corruption. Treisman (2000) found that religious, legal, and economic factors contribute to corruption. Continuous democracy over a long period and political stability are also shown to reduce corruption (Serra, 2006).

Our study empirically examines corruption, explicitly focusing on revolutions. We utilize data on nonviolent and violent revolutionary campaigns from 1900–2019 (Chenoweth & Shay, 2020) and corruption from the Varieties of Democracy Index (Coppedge & Gerring, 2022). We employ a diverse set of analytical tools. These include fixed-effect models, which incorporate time trends for each country and allow for the effect of the control variable (e.g., education or wealth) to be moderated by fixed-effects, as well as randomization inference tests.

In examining successful violent and nonviolent revolutions on corruption levels, we present a nuanced analysis that challenges conventional expectations regarding the efficacy of revolutions in curbing corruption. Our models suggest that successful violent and nonviolent revolutions have null effects on corruption, contradicting the claims made by revolutionary participants. Our paper demonstrates that corruption is a sticky problem, remaining consistent even when confronted with a drastic measure like a successful revolution.

Education plays a transformative role in shaping individuals’ preferences toward nonviolence and augmenting their organizational capacities for orchestrating successful nonviolent protests, rendering nonviolent tactics more appealing and viable for educated protesters when compared to their inclination towards violent tactics (Ustyuzhanin & Korotayev, 2023; Dahlum, 2019). Our findings reveal compelling evidence that violent revolutions, when moderated through education, exhibit a statistically significant increase in corruption. Conversely, nonviolent revolutions, similarly moderated through education, demonstrate a slight but statistically significant decrease in corruption.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the literature on corruption and revolutions. Section 3 outlines our data and methods. Section 4 shows our results. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss our results and conclude.

2 Literature

Corruption impacts several vital markers of development. Research has demonstrated that high levels of corruption limit economic growth and misallocate entrepreneurial talent and investment (Acemoglu & Verdier, 1998; Mironov & Zhuravskaya, 2016; Boudreaux et al., 2018; Bjørnskov, 2012; Sequeira & Djankov, 2014; Goel & Saunoris, 2014; Dutta & Sobel, 2016; Dutta et al., 2013; Mitchell & Campbell, 2009). This misallocation is attributed to the fact that in countries lacking economic freedom, some corruption enables entrepreneurs to evade over-regulation and expedite the entrepreneurial process. Corruption requiring a greasing of the wheels limits nascent entrepreneurship and competition (Chowdhury et al., 2015; Chowdhury & Audretsch, 2021; Acemoglu & Verdier, 2000; Audretsch et al., 2022; Saha & Sen, 2021). Economically disadvantaged individuals (Justesen & Bjørnskov, 2014) and women (Statnik et al., 2023) bear higher costs of corruption than richer men. Corruption increases income inequality (Boudreaux, 2014) and threatens the lives of journalists (Bjørnskov & Freytag, 2016). The literature is mixed on the role of corruption in foreign direct investment (FDI), with some scholars saying corruption limits FDI (Gründler & Potrafke, 2019; Zakharov, 2019; Javorcik & Wei, 2009; Cruz & Sedai, 2021) and, others saying it increases FDI (Egger & Winner, 2005). Corruption is also a push factor for international migration (Dimant et al., 2013).

The literature outlines three competing theories on the relationship between corruption and revolution. First, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine contended that violent revolutions are necessary to eliminate systemic corruption when governance concentrates power without accountability (Paine, 1791). Second, Tullock (1971) provided a rational choice explanation for the post-revolution persistence of corruption due to incentive structures for new leaders. Third, Burke (1912) argued that stable institutions evolving to prevent corruption are destabilized by sudden revolutions.

The first theory, stemming from the writings of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine (Woods, 2008; Paine, 1791), posits that violent revolutions respond to autocratic and corrupt governments. According to this perspective, social movements can effectively eliminate corruption, as exemplified by the case of the American Revolution and other similar movements. Jefferson and Paine argued that revolutions are necessary to limit corruption when all else fails. Countries with constitutions providing a higher concentration of power (de Viteri Vázquez & Bjørnskov, 2020), weak governance structures (Shleifer & Vishny, 1993), an unwieldy military-industrial complex (Coyne et al., 2016; Dimant et al., 2022; Goel & Saunoris, 2016), financial secrecy in politics (Djankov et al., 2010), or countries without democratic elections or term limits (Campante et al., 2009; Ferraz & Finan, 2011) are associated with corruption. A revolution may be necessary to change these formal institutions. Similarly, procedural formalism in the legal system is associated with higher levels of corruption (Djankov et al., 2002). For example, legal origins explain elevated levels of corruption in Louisiana (Callais, 2021). Altering these governance systems may require radical actions. Marginal changes in corruption enforcement may increase corruption rather than decrease it, and therefore, revolutionary methods are required (Kugler et al., 2005).

This revolutionary theory by Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine suggests that unchecked leaders exert political and economic power over citizens, much like economic agents lacking budget constraints. Citizens who violently overthrow their leaders serve in the first instance to remove the offending party and thus limit further expenditures. The second order effect is to demonstrate to successors that violations of the public’s trust will be handled with extreme prejudice, counteracting the short-term benefits from expropriation. Citizens may also reconfigure the political rules to curb future corruption after their violent revolution. If this hypothesis is correct, levels of corruption will decrease after a violent revolution. Public choice theorists, such as Buchanan and Di Pierro (1969), concur that revolutions may yield pragmatic benefits. Their perspective hinges on the observation that in democracies, voters frequently erode liberty gradually. However, voters may suddenly awaken to an acute loss of freedom, particularly during crises, and demand a reversal. Buchanan was sanguine on revolutions and mentioned that these constitutional moments need not be spurred by violence.

Instead of violent tactics, citizens may use forms of civil disobedience, protests, boycotts, strikes, and other means of non-cooperation. The Arab Spring movement responded to police corruption, with some countries using nonviolent methods (Stephan & Chenoweth, 2008). Nonviolent movements are used by citizens to react to corruption or autocratic tendencies, especially when democratic means of regime change are denied, and it is reasonable to assume that these efforts will limit corruption. The literature finds strong evidence that nonviolent resistance campaigns, mass mobilization, and diverse forms of protest positively impact electoral democracy, liberal democracy, deliberative democracy, and civil liberties compared to violent transitions (Bethke & Pinckney, 2019; Pinckney, 2020b; Fetrati, 2023; Sato & Wahman, 2019; Hellmeier & Bernhard, 2022; Dahlum, 2023; Ammons, 2023). However, Hellmeier and Bernhard (2022) finds that pro-autocratic mobilization reduces democracy, qualifying the positive effects of civil resistance movements. This literature suggests that nonviolent resistance facilitates democracy, but mobilization’s impacts depend on the protesters’ goals.

Research indicates that civil resistance campaigns engender greater citizen participation than coups and violent methods (Chenoweth & Stephan, 2011; Chenoweth, 2021). Empirical findings in the literature comport with the theory that social movements embody properties of emergent order and polycentricity (Novak, 2021). Whereas the classic public choice treatment of violent revolutions (Tullock, 1971) and more modern papers (Svolik, 2009, 2012) show that, in theory and practice, violent revolutions are usually carried out by political rivals.

In nonviolent revolutions, citizens employ specific tactics to curb corruption and enhance governance (Ammons & Coyne, 2020). Primarily, these mechanisms, including mass protests, sustained lobbying, and strategic non-cooperation, revolve around the mobilization of large, diverse groups in civil resistance movements, which apply pressure on existing corrupt regimes without resorting to violence. These nonviolent campaigns facilitate elite defections from the regime and create opportunities for concessions, effectively dismantling the pillars of corrupt governance. These movements’ inclusive and participatory nature fosters a culture of transparency and accountability, laying the groundwork for more democratic and less corrupt post-revolution governance structures. Unlike violent revolutions, nonviolent movements sustain and support civil society, which provides a long-term check on government power. This hypothesis predicts that levels of corruption will decrease after a nonviolent revolution.

The second theory offered by Tullock (1971) provides a rational choice explanation for why we see institutional persistence after violent revolutions. Collective action problems abound in social movements because each additional participant contributes marginally less than the previous participant; monitoring and incentivizing participation becomes increasingly challenging as movements grow (Leeson, 2010). Successful revolutionary movements use selective incentives or rents to movement leaders that overcome collective action problems. Still, the incentives generate new leaders who are just as corrupt as the previous administration. This hypothesis predicts stability rather than a shift away from corruption or toward additional misconduct by state officials.

Research reveals significant persistence in corruption levels despite attempted interventions. Simply informing voters about corruption fosters political disengagement rather than reform (Chong et al., 2015). Economic models further demonstrate how inequality and injustice interventions fail to curb corruption and, instead, perpetuate existing systems (Alesina & Angeletos, 2005). Post-Soviet Eastern European countries (Johnson et al., 1997) and Post-Soviet Russia (Blanchard & Shleifer, 2001; Schulze et al., 2016) experienced rampant corruption similar to communist eras, defying expectations of change validating Tullock’s institutional persistence theory.

Anti-corruption policies show short-term gains; however, in the long-term, corruption rebounds to previous norms (Olken & Pande, 2012). Multiple studies substantiate that stable equilibrium in corruption rates is resistant to vary from the reform efforts (Haque & Kneller, 2009). Furthermore, factors beyond public governance consistently better explain corruption levels, including private sector norms, financial institutions, and human capital (Colonnelli et al., 2022). Regional variations eclipse broad country-level predictors of corruption, suggesting null results from country-specific interventions (Goel & Saunoris, 2022; Becker et al., 2009; Kutlu & Mao, 2023).

Individual attributes offer additional insights. A higher intelligence score is associated with less corruption (Potrafke, 2012), implying educational and nutritional improvements may alter corruption in the long run, but corruption levels will resist rapid change. Parking violations among foreign diplomats correlate strongly with home corruption rates, signaling cultural endogeneity of corruption (Fisman & Miguel, 2007), and immigrants transport their corruption norms from home (Dimant et al., 2015), suggesting corruption persists within cultures.

The persistence view is grounded in economic theory. Tullock provides a rational choice explanation for institutional persistence after violent revolutions. Individuals, acting rationally, weigh the potential personal gains against the costs of participating in revolutionary activities. The prospect of significant personal gains, or rents, may incentivize participation and leadership in revolutionary movements. However, these incentives often lead to the emergence of new leaders who are primarily motivated by personal gain rather than genuine reform, perpetuating the cycle of corruption. This theory is grounded in rent-seeking behavior, where individuals or groups seek to increase their share of existing wealth without creating new wealth. Furthermore, the theory posits that the public choice mechanisms involved in revolutions do not necessarily disrupt the underlying economic and cultural systems that foster corruption. Instead, they may merely replace one set of self-interested actors with another, leading to a continuity of corrupt practices.

The persistence view is also bolstered by Caplan (2008), who critiques Von Mises’s (1985) “Democracy–Dictatorship Equivalence Theorem,” which states that democracy and dictatorship produce similar/equivalent policies due to the overriding influence of public opinion on leaders, despite their differences in structure, because people power movements will replace dictators. Instead, Caplan (2008) claims that while revolutions may occur, the policy changes will be minimal because of shared preferences among the electorate and a status quo bias. Holcombe and Boudreaux (2013) empirically show that autocrats with the highest average annual improvement in economic institutions during their tenures tend to have longer tenures on average, which in hindsight suggests that countries with market institutions are less likely to experience a revolution. If this hypothesis is correct, the data will not show changes in corruption after a revolution.

The third view of Burke (1912) argues that stable institutions protect against corruption, and revolutions threaten stability and increase corruption. In this view, political, economic, and social structures slowly adapt to their environment, and revolutionary actions disrupt the evolutionary process. Burke (1912) developed the theory challenging the benefits of revolution while highlighting the importance of tradition, social continuity, and gradual improvements to institutions. Burke’s skepticism of rapid change was rooted in recognizing society’s complex organic nature and social contract theory. This contractual view infers a moral duty to obey the law to uphold society’s legal, social, and ethical fabric. Eroding the social contract’s power through revolution would make society more susceptible to degeneration and corruption.

Burke’s view is supported by research showing that longstanding social, economic, and democratic procedures limit corruption. Cultures supporting rule-breaking behavior are associated with higher levels of corruption (Gächter & Schulz, 2016), and there is an inverse relationship between social trust and corruption (Bjørnskov, 2011; Amini et al., 2022). Leadership matters for limiting corruption, but cultural or religious constraints also play a pivotal role (Gutmann & Lucas, 2018). Economic factors like investments in education (Glaeser & Saks, 2006), economic development, and globalization (Sequeira & Djankov, 2014) reduce corruption. Elections increase perceptions of corruption, and while the mechanism for this fact is understudied, it is plausible that democratic engagement exposes political issues leading to their resolution (Potrafke, 2019). These studies suggest that marginal improvements to cultural, economic, and legal systems will diminish corruption in the long run. However, overturning the system threatens social, economic, and political stability, primarily through violence.

The relationship between economic development, education, and intelligence with corruption is nuanced and supported by empirical results. Glaeser and Saks (2006) use data from convictions of government officials in the US to identify the driver of these related variables. Since most corruption measures rely on survey results, it is difficult to determine if less-educated individuals think more corruption exists or if economic development shifts the opportunity costs of engaging in corruption. Intelligence could also relate to corruption because corruption could be profit maximizing in the short run, but more competent individuals realize that in the long run, corruption reduces wealth. However, Glaeser’s method warns that these findings are not fixed, given genetics or wealth. Instead, Glaeser’s data enables him to show that education drives development by offering greater economic opportunity. Next, economic development allows individuals to police government officials because basic needs have been met, and with economic development, individuals have a greater capacity and desire to monitor government corruption. This analysis argues that instead of good governance generating economic development and education, education creates economic development, which produces good government. As first articulated in The Wealth of Nations Chapter IV of Book III, Adam Smith describes the effects of merchants moving to cities, expanding labor division and workers’ dexterity, and investing in good government (Smith, 1869).

In addition to these indirect factors, direct interventions short of revolution could produce benefits. Independent media is associated with lower levels of corruption, and economic development is associated with introducing independent media (Petrova, 2011; Freille et al., 2007). Shrinking voting districts (Persson et al., 2003), financial audits (Colonnelli & Prem, 2022; Avis et al., 2018), and technological innovation (Hanna, 2017; Muralidharan et al., 2023; Darusalam et al., 2019; Gans-Morse et al., 2018) may reduce corruption levels absent revolutions. Financial audits’ long-term effects are attenuated as individuals adjust to the new institutional environment (Ferraz & Finan, 2018), and this phenomenon is likely after most marginal changes.

Violent revolutions may not have the intended effects, and researchers should be aware of anti-corruption measures’ unintended consequences and second-order effects (Fisman & Golden, 2017). Research indicates that coups diminish institutional quality and increase corruption (Bennett et al., 2021). Political assassinations and regime instability are linked to greater levels of corruption (Goel & Saunoris, 2017). Theories suggest that most revolutionary paths lead to authoritarianism (Goldstone, 2023).

The economic rationale for predicting that marginal improvements will lead to decreased corruption hinges on the principle that stable institutions constrain political behavior. Similarly, cultural norms discouraging rule-breaking may limit corruption and be eroded by radical change. Incremental investments in human capital spur economic growth and foster good governance, echoing Adam Smith’s theory that development and education precede effective governance. Direct interventions like promoting independent media, resizing voting districts, and implementing financial audits and technological innovations are also instrumental. Together, this hypothesis predicts that incremental improvements are superior to revolution. If our data presents increases in corruption after a revolution, this hypothesis is confirmed.

To summarize, the three world views embodied by Jefferson, Tullock, and Burke represent contesting theories of political economy. However, these three hypotheses may be empirically evaluated with our data on revolutions. First, we consider the theory based on Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine’s revolutionary perspective, and we test the hypothesis that nonviolent or violent revolutions positively influence corruption mitigation. This hypothesis is based mainly on improving institutions with new leaders and governance systems. Second, the theory based on Tullock’s rational choice perspective is that revolutions lead to institutional persistence because the promise of economic rents induces revolutionary actions and ensures corruption persists at current levels. If this theory is correct, we should see the null effects of the revolution on corruption. Third, the theory based on Burke’s stable institutions perspective suggests that revolution has adverse effects. It indicates that counter-corruption methods that do not involve revolutions are better suited to fighting corruption than dismantling stable institutions.

3 Data and methods

Chenoweth and Shay (2020) catalog nonviolent and violent campaigns from 1900 to 2019. Their data includes maximalist citizen campaigns against the state, meaning that the campaign’s goal was regime change, territorial independence, or independence from a colonial power. The data examines social movements with over 1000 citizens.

A violent campaign employs armed forces to overcome the regime’s security forces, defeat the state militarily, and recruit participants to engage in combat. In contrast, nonviolent campaigns mobilize activists for peaceful dissent, rule-breaking, delegitimizing authorities, and avoiding violence when facing repression. A campaign with sporadic violence accompanying widespread nonviolent resistance is still primarily nonviolent, whereas groups explicitly created to use violence denote a violent campaign.

The Varieties of Democracy project comprehensively evaluates democratization across multiple principles, each with constituent components and specific indicators, enabled by a global database tracking over 600 metrics annually from 1789 (Coppedge & Gerring, 2022). This collaboration among diverse experts pioneers explaining democracy varieties and causal mechanisms among aspects and disaggregating the concept from a single to multiple outcomes.

Our research defines corruption as “Regime corruption: To what extent do political actors use political office for private or political gain?” from the Varieties of Democracy database. Varieties of Democracy database defines systems of neo-patrimonial rule; politicians use their offices for private and/or political gain. This indicator focuses on a more specific set of actors, those who occupy political offices, and a more specific set of corrupt acts that relate more closely to the conceptualization of corruption in the literature on neo-patrimonial rule. Lower corruption scores are normatively desirable, or smaller numbers indicate that the society has less corruption. Therefore, the index is formed by taking the reversed point estimates (so that higher scores represent more regime corruption) from a Bayesian factor analysis model of the indicators for executive embezzlement, executive bribes, legislative corruption, and judicial corruption. Each indicator is also part of the Varieties of Democracy database.Footnote 3

3.1 Baseline model

We regress the corruption variable (\(Corruption_{ct}\)) on the revolution variable (\(Revolution_{ct}\)) in equation 1.

c and t represent indices for country and time, respectively. The dependent variable is \(Corruption_{ct}\), capturing the corruption index. \(Corruption_{ct}\) is corruption index that ranges from 0 to 1 from no corruption to full-corruption.

We define Revolution as a binary indicator variable, 1 for post-successful one-time revolution and 0 otherwise. However, we define the treatment indicator by categorizing countries into two groups. The first comprises a comparison group, \(treat = 0\), countries that have not reported any instances of violent or nonviolent revolutions or conflicts.Footnote 4 The second consists of treatment group \(treat = 1\), countries that have experienced only one successful revolution. We distinguish two types within the treatment group based on the nature of the revolution, whether violent or nonviolent.

The first group pertains to countries that experienced only one success in violent revolution.Footnote 5 The second involves countries that underwent only one success nonviolent revolution.Footnote 6 From both of these groups we exclude Algeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Georgia, Hungary, Mexico, Morocco, Pakistan, and Russia, because these countries have both one successful violent as well as nonviolent revolution.

In Equation 1, the parameter \(\alpha\) represents the average corruption index value when countries have not experienced any revolution, while \(\beta\) signifies the extent to which the average corruption index during the post-successful revolution compares to the average when countries have not experienced any revolution.

3.2 Two-way fixed effects model

Equation 2 shows a regression model with a two-way fixed effects model.

The terms \(\mu _c\) and \(\nu _t\) denote the additive fixed effects associated with countries and periods, respectively. We employ three distinct models: the first includes only country-fixed effects, the second incorporates solely year-fixed effects, and the third encompasses both country and year-fixed effects.

Country-fixed effects eliminate variations in the corruption rate correlated with factors persistently fixed at the country level throughout the sample period. These factors encompass unmeasured socio-economic, cultural, political, and demographic influences. On the other hand, year-fixed effects account for temporal variations that uniformly affect all countries for a specific year, such as common shocks like overall economic conditions or temporal changes in the business cycle particular to a given year.

Cultural or country-specific factors play a critical role in several theories outlined previously. For example, many justifications for violent revolution rest on the high costs of corrupt and ineffective formal institutions. These may or may not persist after a revolution, and the countries undergoing revolutions are not randomly selected.

3.3 Country-specific trends

The trend we perceive in corruption may be more than just due to our definition of treatment assignment (\(Revolution_{ct}\)). Unit-fixed and time-fixed effects may not adequately adjust for country-specific trends in corruption. Addressing this challenge involves identifying and incorporating country-specific trends, which can help adjust for trends in the outcome variable (\(Corruption_{ct}\)) and not influenced by treatment assignment (\(Revolution_{ct}\)). The unobservable latent factors, such as political, cultural, or linguistic changes, may impact each unit’s specific outcome. We introduce varying slopes to control for heterogeneous effects across groups flexibly. We incorporate time corruption trends for each country to capture the country-specific trend in the outcome variable \(Corruption_{ct}\).

For all our regressions, we include the Newey-West standard errors to correct for potential heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in the residuals of a regression model.

4 Results

4.1 Summary statistics

We begin our analysis by including summary statistics of corruption indices for each country in Table 1. Countries are listed in the alphabetic order.

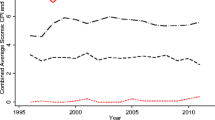

Figure 1 depicts the average corruption trend among comparison group countries with no violent or nonviolent revolution in a solid line, countries with only one successful nonviolent revolution in a loosely dotted line, and countries with only one successful violent revolution in a dashed line.

4.2 Impact of successful violent revolutions on corruption

Next, we present the results illustrating the extent to which successful violent revolutions affect corruption in Table 2. We start with a naive regression in Column (1), revealing that, on average, countries with no violent or nonviolent revolution periods have a corruption index of 0.327, which is Rwanda’s score in 2022. In contrast, countries experiencing successful violent revolutions show an additional corruption index of 0.199 on average or \(\frac{0.199}{0.327}\times 100 \approx 61\%\) more than the comparison countries. This increment can be par at the level of Cuba in 2022 with a score of 0.531 and Ukraine in 2022 with 0.535.

Table 2, Column (1), reports an estimate of a 0.199 increase in the corruption index. However, this estimate may be biased since each country may perceive corruption differently, given the survey-based nature of the data. In Column (2), we introduce country-fixed effects of accounting for factors related to unmeasured socio-economic, cultural, political, and demographic influences specific to each country. The estimate reveals a 0.044 increase in corruption in the post-revolution period. We include only year-fixed impacts to account for unobserved but uniform heterogeneity that affects all countries in a specific year (Column 3). In that case, the corruption index increases by 0.187, which is very close to the estimate reported in Column (1). However, when we include the two-way fixed effects model in Column (4), we find that countries experiencing successful violent revolutions exhibit no statistically significant changes in corruption. We should remain cautious in interpreting these results. Next, we introduce country-specific trend effects in Column (5), which includes linear trend-specific fixed effects. We observe the corruption index increases by 0.052, which mildly supports the view that violent revolutions increase corruption and that stability and incremental changes are superior (Burke, 1912). However, the effects shown in Column (5) are small.

4.3 Impact of successful nonviolent revolutions on corruption

In Table 3, we examine the impact of countries experiencing successful nonviolent revolutions on corruption. In Column (1), the average corruption index for countries with no violent or nonviolent revolutions is 0.331, similar to the Dominican Republic and China in 2022 with a score of 0.342 and 0.351, respectively. In contrast, countries undergoing successful nonviolent post-revolutions exhibit an additional average corruption index of 0.106, close to Somaliland and Mexico’s corruption scores of 0.428 and 0.472 in 2022, respectively. This effect represents approximately a 30% increase compared to the comparison countries.

Columns (2) and (3), where country-fixed effects and year-fixed effects are incorporated, reveal an increase in corruption of 0.045 units. Moving to Column (4), which encompasses country and year-fixed effects, we observe a null effect. Similarly, in Column (5), where country-specific trend fixed effects are included, we also find a null effect.

4.4 Randomization inference test

We perform randomization inference tests by randomly assigning revolutions to countries over 1000 iterations to estimate the impact of such randomly assigned revolutions on corruption. Through these 1000 iterations, we derive a distribution in Fig. 2 Panel (a) representing the impact of randomly assigned successful violent revolutions on corruption. Similarly, Fig. 2 Panel (b) illustrates the effect of randomly assigned successful nonviolent revolutions on corruption, utilizing the estimated regression from Equation 3.

We present the 90% confidence interval in both Panels with a loosely dotted line. Notably, we incorporate the treatment effect from Table 2, Column (5), into Panel (a), represented by a dashed line. Additionally, the treatment effect from Table 3, Column (5), is depicted in Panel (b) with a dashed line. We observe that the treatment effects reported in Tables 2 and 3, specifically in Column (5), fall within the 90% confidence interval of the randomized inference test, suggesting it is statistically plausible that the occurrence of a successful violent or nonviolent revolution does not lead to significant changes in corruption.

4.5 Moderating role of growth and education

Some studies show that GDP is a robust predictor of nonviolent onset (Pinckney, 2020a; Thurber, 2018). Other research questions GDP growth’s predictive power but concedes that poverty rates are negatively associated with nonviolent campaigns (Chenoweth & Ulfelder, 2017). Higher GDP is associated with greater use of political jiu-jitsu, meaning that when the state applies repression to civil resistance movements, the movements respond with greater levels of non-cooperation. This finding is explained by a larger GDP associated with a greater capacity for elites to harm political actors with boycotts, strikes, and withholding taxation (Sutton et al., 2014). When a metric of globalization is included in the analysis of nonviolent campaign onset, GDP loses significance, indicating that other aspects of globalization besides wealth drive the results (Karakaya, 2018).

Table 4 presents odd-numbered Columns (1), (3), (5), and (7), which incorporate year, country, and country-specific linear trend fixed effects. Even-numbered Columns (2), (4), (6), and (8) additionally allow for the impact of revolution to be moderated by selected control variables (growth or education), varying by country fixed-effect.

Panel (a) in Columns (1) and (2) explores the moderating role of growth, while Columns (3) and (4) examine the moderating role of education in the impact of successful violent revolutions on corruption. All estimates in Panel (a) indicate that successful violent revolutions lead to increased corruption.

Panel (b) in Columns (5) and (6) investigates the moderating role of growth, while Columns (7) and (8) explore the moderating role of education in the impact of successful nonviolent revolutions on corruption. All Panel (b) estimates suggest that successful nonviolent revolutions marginally reduce corruption.

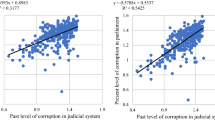

We offer the randomization inference test in Fig. 3 to ensure our results are not due to chance. In Fig. 3, we present four Panels depicting the distribution of randomized inferences obtained by randomizing 1000 iterations of successful revolutions’ impact on corruption. A loosely dotted line represents the 90% confidence interval, and the estimated treatment effect for the corresponding Column in Table 4 is depicted with a dashed line.

Suppose the reported treatment effect, depicted by the dashed line in Table 4, extends beyond the range defined by the loosely dotted lines. In that case, it substantiates the statistical plausibility of the reported treatment effect. However, if the dashed line falls within the loosely dotted lines, the reported treatment effect is deemed invalid, notwithstanding its statistical significance as observed in Table 4.

Figure 3, Panel (a), illustrates the growth-moderated impact of the randomized inference-based successful violent revolution on corruption, indicating the improbability of a significant effect on corruption. Similarly, Panel (c) suggests that it is unlikely for a successful nonviolent revolution, moderated via growth, to impact corruption significantly.

Panel (b) reveals that a successful violent revolution, moderated via education, significantly increases corruption. Conversely, Panel (d) demonstrates the improbability of a successful nonviolent revolution, moderated via education, to reduce corruption.

5 Discussion and conclusion

Our study examines the impact of successful nonviolent and violent revolutions on corruption. We present three key findings. First, results from randomization inference tests in Fig. 2 incorporating estimates from Tables 2 and 3 suggest that revolutions do not have a significant effect on corruption. As in the opening story of Chad, in Sect. 1, revolutions do not change levels of corruption in a meaningful way. One theoretical argument could be the ideas of Tullock (1971) that corruption is incredibly difficult to change partly because of the selective incentives required to solve the collective action problems involved in revolutions.

Second, our analysis indicates a decrease in corruption linked to education, as shown in Table 4, Columns (3) and (7). Better educated citizens tend to hold governments more accountable, and this finding holds in US county-level data on education and corruption (Glaeser & Saks, 2006). Additionally, more intelligent officials likely weigh the risks of engaging in corruption higher than officials with less education and lower opportunity costs in the market.

Third, upon adjusting for the moderating effect of education, our analysis reveals an increase in corruption following a successful violent revolution. This observation is supported by results from randomization inference tests depicted in Fig. 3, Panel (b), and further corroborated by Table 4, Columns (4). These results may be due to the “violence trap” articulated by North et al. (2009). In societies where violence is a common tool for maintaining social order and protecting the interests of elites, any move towards less corruption, more inclusive governance, and broader access to resources threatens the existing balance of power among these elites, and these elites use violence or threats of violence to maintain power. Research demonstrates that low state capacity, measured by tax receipts, is associated with high levels of corruption (Tagem & Morrissey, 2023).

Policymakers, academics, and citizens should explore alternative means of combating corruption. Social trust, religious adherence, globalization, voting, education, economic freedom, and independent media are associated with lower levels of corruption in the long run. The benefits of these reforms on corruption often face long lags, especially in deeply corrupt states. Additional research should explore the impacts of alternative interventions to limit corruption.

Notes

For more details, see “Regime corruption” in code book https://v-dem.net/documents/24/codebook_v13.pdf.

Countries that have not reported any instances of violent or nonviolent revolutions or conflicts includes: Australia, Barbados, Belgium, Bhutan, Botswana, Canada, Cape Verde, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ireland, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Luxembourg, Malta, Mauritius, Netherlands, New Zealand, North Korea, Palestine/British Mandate, Palestine/Gaza, Qatar, Sao Tome and Principe, Seychelles, Singapore, Slovakia, Solomon Islands, Somaliland, South Yemen, Sweden, Switzerland, The Gambia, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, and Zanzibar.

Countries that experienced only one success in violent revolution include: Algeria (1962), Angola (1974), Argentina (1955), Burundi (1992), Chad (1990), Chile (1973), Costa Rica (1948), Cuba, (1959), Cyprus, (1959), the Democratic Republic of the Congo, (1997), Ethiopia, (1991), Georgia, (2008), Guatemala, (1954), Guinea-Bissau, (1974), Hungary, (1920), Indonesia, (1949), Iran, (1909), Libya, (2011), Mexico, (1920), Morocco, (1956), Mozambique, (1975), Namibia, (1988), Pakistan, (1971), Russia, (1917), Spain, (1939), Tunisia, (1954), and Uganda, (1986).

Countries that experienced only one success in nonviolent revolution include: Albania, (1991), Algeria, (2019), Armenia, (2018), Belarus, (1991), Bulgaria, (2014), Burkina Faso, (2014), Cameroon, (1991), Central African Republic, (1993), Colombia, (1957), Croatia, (2000), Czechia, (1989), Democratic Republic of the Congo, (2018), Dominican Republic, (1962), Estonia, (1991), Fiji, (2000), Georgia, (2003), Germany, (1924), Greece, (1974), Guyana, (1992), Hungary, (1989), Iceland, (2009), India, (1977), Kenya, (1991), Latvia, (1991), Lithuania, (1991), Mali, (1991), Mexico, (2000), Moldova, (2009), Mongolia, (1990), Morocco, (2006), Niger, (1992), Nigeria, (1999), North Macedonia, (2017), Pakistan, (2008), Paraguay, (1999), Peru, (2000), Poland, (1989), Portugal, (1974), Russia, (1991), Serbia, (2000), Suriname, (2000), Taiwan, (1985), Togo, (2005), Ukraine, (1990), Uruguay, (1985), Yemen, (2012), and Zimbabwe, (2017).

References

Acemoglu, D., & Verdier, T. (1998). Property rights, corruption and the allocation of talent: A general equilibrium approach. The Economic Journal, 108(450), 1381–1403.

Acemoglu, D., & Verdier, T. (2000). The choice between market failures and corruption. The American Economic Review, 90(1), 194–211.

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. (1999). Rents, competition, and corruption. American Economic Review, 89(4), 982–993.

Aidt, T. S. (2003). Economic analysis of corruption: A survey. The Economic Journal, 113(491), F632–F652.

Alesina, A., & Angeletos, G.-M. (2005). Corruption, inequality, and fairness. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(7), 1227–1244.

Amini, C., Douarin, E., & Hinks, T. (2022). Individualism and attitudes towards reporting corruption: Evidence from post-communist economies. Journal of Institutional Economics, 18(1), 85–100.

Ammons, J. (2023). Institutional effects of nonviolent and violent revolutions. GMU Working Paper in Economics.

Ammons, J., & Coyne, C. J. (2020). Nonviolent action. In S. Haeffele & V. H. Storr (Eds.), Bottom-up Responses to Crisis, Mercatus Studies in Political and Social Economy (pp. 29–55). New York: Springer International Publishing.

Apergis, N., Dincer, O. C., & Payne, J. E. (2012). Live free or bribe: On the causal dynamics between economic freedom and corruption in U.S. states. European Journal of Political Economy, 28(2), 215–226.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., & Desai, S. (2022). The role of institutions in latent and emergent entrepreneurship. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121263.

Avis, E., Ferraz, C., & Finan, F. (2018). Do government audits reduce corruption? Estimating the impacts of exposing corrupt politicians. Journal of Political Economy, 126(5), 1912–1964.

Banerjee, A. V. (1997). A theory of misgovernance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1289–1332.

Barr, A., & Serra, D. (2010). Corruption and culture: An experimental analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 94(11–12), 862–869.

Becker, S. O., Egger, P. H., & Seidel, T. (2009). Common political culture: Evidence on regional corruption contagion. European Journal of Political Economy, 25(3), 300–310.

Bennett, D. L., Bjørnskov, C., & Gohmann, S. F. (2021). Coups, regime transitions, and institutional consequences. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(2), 627–643.

Bethke, F. S., & Pinckney, J. (2019). Non-violent resistance and the quality of democracy. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 38(5), 503–523.

Bjørnskov, C. (2011). Combating corruption: On the interplay between institutional quality and social trust. The Journal of Law & Economics, 54(1), 135–159.

Bjørnskov, C. (2012). Can bribes buy protection against international competition? Review of World Economics, 148(4), 751–775.

Bjørnskov, C., & Freytag, A. (2016). An offer you can’t refuse: Murdering journalists as an enforcement mechanism of corrupt deals. Public Choice, 167(3), 221–243.

Blanchard, O., & Shleifer, A. (2001). Federalism with and without political centralization: China versus Russia. IMF Staff Papers, 48, 171–179.

Boudreaux, C. J. (2014). Jumping off of the Great Gatsby curve: How institutions facilitate entrepreneurship and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Institutional Economics, 10(2), 231–255.

Boudreaux, C. J., Nikolaev, B. N., & Holcombe, R. G. (2018). Corruption and destructive entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 51(1), 181–202.

Buchanan, J. M., & Di Pierro, A. (1969). Pragmatic reform and constitutional revolution. Ethics, 79(2), 95–104.

Burke, E. (1912). Reflections on the French Revolution (Vol. 460). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Callais, J. T. (2021). Laissez les bons temps rouler? The persistent effect French civil law has on corruption, institutions, and incomes in Louisiana. Journal of Institutional Economics, 17(4), 663–680.

Campante, F. R., Chor, D., & Do, Q.-A. (2009). Instability and the incentives for corruption. Economics & Politics, 21(1), 42–92.

Caplan, B. (2008). Mises’ democracy-dictatorship equivalence theorem: A critique. The Review of Austrian Economics, 21, 45–59.

Chenoweth, E. (2021). Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs to Know®. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chenoweth, E., & Shay, C. W. (2020). NAVCO 1.3 dataset.

Chenoweth, E., & Stephan, M. J. (2011). Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chenoweth, E., & Ulfelder, J. (2017). Can structural conditions explain the onset of nonviolent uprisings? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 298–324.

Chong, A., De La, O., Karlan, A. L., & Wantchekon, L. (2015). Does corruption information inspire the fight or quash the hope? A field experiment in Mexico on voter turnout, choice, and party identification. The Journal of Politics, 77(1), 55–71.

Chowdhury, F., & Audretsch, D. B. (2021). Do corruption and regulations matter for home country nascent international entrepreneurship? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(3), 720–759.

Chowdhury, F., Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2015). Does corruption matter for international entrepreneurship? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 959–980.

Colonnelli, E., Gallego, J., & Prem, M. (2022). What predicts corruption? In A Modern Guide to the Economics of Crime, pages 345–373. Edward Elgar Publishing. Section: A Modern Guide to the Economics of Crime.

Colonnelli, E., & Prem, M. (2022). Corruption and firms. The Review of Economic Studies, 89(2), 695–732.

Coppedge, M., & Gerring, J. (2022). V-Dem dataset 2022.

Coyne, C. J., Michaluk, C., & Reese, R. (2016). Unproductive entrepreneurship in US military contracting. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 5(2), 221–239.

Cruz, M. D., & Sedai, A. K. (2021). The effect of corruption on foreign direct investment in natural resources: A Latin American case study.

Dahlum, S. (2019). Students in the streets: Education and nonviolent protest. Comparative Political Studies, 52(2), 277–309.

Dahlum, S. (2023). Joining forces: Social coalitions and democratic revolutions. Journal of Peace Research, 60(1), 42–57.

Darusalam, D., Said, J., Omar, N., Janssen, M., & Sohag, K. (2019). The diffusion of ICT for corruption detection in open government data. Knowledge Engineering and Data Science, 2(1), 10–18.

de Viteri Vázquez, A. S., & Bjørnskov, C. (2020). Constitutional power concentration and corruption: Evidence from Latin America and the Caribbean. Constitutional Political Economy, 31(4), 509–536.

Dimant, E., Krieger, T., & Meierrieks, D. (2013). The effect of corruption on migration, 1985–2000. Applied Economics Letters, 20(13), 1270–1274.

Dimant, E., Krieger, T., & Meierrieks, D. (2022). Paying them to hate us: The effect of U.S. military aid on anti-American terrorism, 1968-2018.

Dimant, E., Redlin, M., & Krieger, T. (2015). A crook is a crook ... but is he still a crook abroad? On the effect of immigration on destination-country corruption. German Economic Review, 16(4), 464–489.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de Silane, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). Courts: The Lex Mundi Project.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2010). Disclosure by politicians. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 179–209.

Dutta, N., S. Sobel, R., & Roy, S. (2013). Entrepreneurship and political risk. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 2(2), 130–143.

Dutta, N., & Sobel, R. (2016). Does corruption ever help entrepreneurship? Small Business Economics, 47, 179–199.

Egger, P., & Winner, H. (2005). Evidence on corruption as an incentive for foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy, 21(4), 932–952.

Faria, H. J., Morales, D. R., Pineda, N., & Montesinos, H. M. (2012). Can capitalism restrain public perceived corruption? Some evidence. Journal of Institutional Economics, 8(4), 511–535.

Ferraz, C., & Finan, F. (2011). Electoral accountability and corruption: Evidence from the audits of local governments. American Economic Review, 101(4), 1274–1311.

Ferraz, C., & Finan, F. (2018). Fighting political corruption: Evidence from Brazil. In K. Basu & T. Cordella (Eds.), Institutions, Governance and the Control of Corruption, International Economic Association Series (pp. 253–284). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Fetrati, J. (2023). Non-violent resistance movements and substantive democracy. Democratization, 30(3), 378–397.

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002). Decentralization and corruption: Evidence across countries. Journal of Public Economics, 83(3), 325–345.

Fisman, R., & Golden, M. (2017). How to fight corruption. Science, 356(6340), 803–804.

Fisman, R., & Miguel, E. (2007). Corruption, norms, and legal enforcement: Evidence from diplomatic parking tickets. Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 1020–1048.

Freille, S., Haque, M. E., & Kneller, R. (2007). A contribution to the empirics of press freedom and corruption. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(4), 838–862.

Gans-Morse, J., Borges, M., Makarin, A., Mannah-Blankson, T., Nickow, A., & Zhang, D. (2018). Reducing bureaucratic corruption: Interdisciplinary perspectives on what works. World Development, 105, 171–188.

Glaeser, E. L., & Saks, R. E. (2006). Corruption in America. Journal of Public Economics, 90(6), 1053–1072.

Goel, R. K., & Saunoris, J. W. (2014). Global corruption and the shadow economy: Spatial aspects. Public Choice, 161(1/2), 119–139.

Goel, R. K., & Saunoris, J. W. (2016). Military buildups, economic development and corruption. The Manchester School, 84(6), 697–722.

Goel, R. K., & Saunoris, J. W. (2017). Political uncertainty and international corruption. Applied Economics Letters, 24(18), 1298–1306.

Goel, R. K., & Saunoris, J. W. (2022). Corrupt thy neighbor? New evidence of corruption contagion from bordering nations. Journal of Policy Modeling, 44(3), 635–652.

Goldstone, J. A. (2023). You can’t always get what you want: Why revolutionary outcomes so often diverge from revolutionary goals. Public Choice, 1–16.

Gründler, K., & Potrafke, N. (2019). Corruption and economic growth: New empirical evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 60, 101810.

Gutmann, J., & Lucas, V. (2018). Private-sector corruption: Measurement and cultural origins. Social Indicators Research, 138(2), 747–770.

Gächter, S., & Schulz, J. F. (2016). Intrinsic honesty and the prevalence of rule violations across societies. Nature, 531(7595), 496–499.

Hanna, R. (2017). Technology beats corruption. Science, 355(6322), 244–245.

Haque, M. E., & Kneller, R. (2009). Corruption clubs: Endogenous thresholds in corruption and development. Economics of Governance, 10(4), 345–373.

Hellmeier, S., & Bernhard, M. (2022). Mass mobilization and regime change. Evidence from a new measure of mobilization for democracy and autocracy from 1900 to 2020. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Holcombe, R. G., & Boudreaux, C. J. (2013). Institutional quality and the tenure of autocrats. Public Choice, 156, 409–421.

Holcombe, R. G., & Boudreaux, C. J. (2015). Regulation and corruption. Public Choice, 164(1), 75–85.

Hugo, E., Savage, D. A., Schneider, F., & Torgler, B. (2023). Two sides of the coin: Exploring the duality of corruption in Latin America. Journal of Institutional Economics, 1–15.

Javorcik, B., & Wei, S.-J. (2009). Corruption and cross-border investment in emerging markets: Firm-level evidence. Journal of International Money and Finance, 28(4), 605–624.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., Shleifer, A., Goldman, M. I., & Weitzman, M. L. (1997). The unofficial economy in transition. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1997(2), 159–239.

Justesen, M. K., & Bjørnskov, C. (2014). Exploiting the poor: Bureaucratic corruption and poverty in Africa. World Development, 58, 106–115.

Kaasa, A., & Andriani, L. (2022). Determinants of institutional trust: The role of cultural context. Journal of Institutional Economics, 18(1), 45–65.

Kapur, D. (1998). The State in a Changing World: A Critique of the 1997 World Development Report. Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University.

Karakaya, S. (2018). Globalization and contentious politics: A comparative analysis of nonviolent and violent campaigns. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 35(4), 315–335.

Kugler, M., Verdier, T., & Zenou, Y. (2005). Organized crime, corruption and punishment. Journal of Public Economics, 89(9–10), 1639–1663.

Kutlu, L., & Mao, X. (2023). The effect of corruption control on efficiency spillovers. Journal of Institutional Economics, 1–15.

Leeson, P. T. (2010). Rational choice, round robin, and rebellion: An institutional solution to the problems of revolution. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 73(3), 297–307.

Liu, X. (2016). Corruption culture and corporate misconduct. Journal of Financial Economics, 122(2), 307–327.

Mironov, M., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2016). Corruption in procurement and the political cycle in tunneling: Evidence from financial transactions data. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 8(2), 287–321.

Mitchell, D. T., & Campbell, N. D. (2009). Corruption’s effect on business venturing within the United States. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 68(5), 1135–1152.

Muralidharan, K., Niehaus, P., and Sukhtankar, S. (2023). Identity verification standards in welfare programs: Experimental evidence from India. The Review of Economics and Statistics, pages 1–46.

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., & Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Novak, M. (2021). Freedom in Contention: Social Movements and Liberal Political Economy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Olken, B. A., & Pande, R. (2012). Corruption in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 479–509.

Paine, T. (1791). Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr Burke’s Attack on the French Revolution. JS Jordan.

Pavlik, J. B., & Young, A. T. (2022). Sorting out the aid-corruption nexus. Journal of Institutional Economics, 18(4), 637–653.

Persson, T., Tabellini, G., & Trebbi, F. (2003). Electoral rules and corruption. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(4), 958–989.

Petrova, M. (2011). Newspapers and parties: How advertising revenues created an independent press. American Political Science Review, 105(4), 790–808.

Pinckney, J. (2020). Curving the resource curse: Negative effects of oil and gas revenue on nonviolent resistance campaign onset. Research & Politics, 7(2), 2053168020936890.

Pinckney, J. C. (2020). From Dissent to Democracy: The Promise and Perils of Civil Resistance Transitions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Potrafke, N. (2012). Intelligence and corruption. Economics Letters, 114(1), 109–112.

Potrafke, N. (2019). Electoral cycles in perceived corruption: International empirical evidence. Journal of Comparative Economics, 47(1), 215–224.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1975). The economics of corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 4(2), 187–203.

Saha, S., & Sen, K. (2021). The corruption-growth relationship: Does the political regime matter? Journal of Institutional Economics, 17(2), 243–266.

Sato, Y., & Wahman, M. (2019). Elite coordination and popular protest: The joint effect on democratic change. Democratization, 26(8), 1419–1438.

Schulze, G., Sjahrir, B., & Zakharov, N. (2016). Corruption in Russia. Journal of Law and Economics, 59(1).

Sequeira, S., & Djankov, S. (2014). Corruption and firm behavior: Evidence from African ports. Journal of International Economics, 94(2), 277–294.

Serra, D. (2006). Empirical determinants of corruption: A sensitivity analysis. Public Choice, 126(1–2), 225–256.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1993). Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 599–617.

Smith, A. (1869). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Vol. 1). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Statnik, J.-C., Vu, T.-L.-G., & Weill, L. (2023). Does corruption discourage more female entrepreneurs from applying for credit? Comparative Economic Studies, 65(1), 1–28.

Stephan, M. J., & Chenoweth, E. (2008). Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. International Security, 33(1), 7–44.

Sutton, J., Butcher, C. R., & Svensson, I. (2014). Explaining political jiu-jitsu: Institution-building and the outcomes of regime violence against unarmed protests. Journal of Peace Research, 51(5), 559–573.

Svolik, M. W. (2009). Power sharing and leadership dynamics in authoritarian regimes. American Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 477–494.

Svolik, M. W. (2012). The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tagem, A. M. E., & Morrissey, O. (2023). Institutions and tax capacity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Institutional Economics, 19(3), 332–347.

Thurber, C. (2018). Ethnic barriers to civil resistance. Journal of Global Security Studies, 3(3), 255–270.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 399–457.

Tullock, G. (1971). The paradox of revolution. Public Choice, 11(1), 89–99.

Ustyuzhanin, V., & Korotayev, A. (2023). Education and revolutions: Why do revolutionary uprisings take violent or nonviolent forms? Cross-Cultural Research, page 10693971231162231.

Von Mises, L. (1985). Theory and History. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Woods, B. F. (2008). Thomas Jefferson: Thoughts on War and Revolution (1st ed.). New York: Algora Publishing.

Zakharov, N. (2019). Does corruption hinder investment? Evidence from Russian regions. European Journal of Political Economy, 56, 39–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ammons, J.D., Shakya, S. Revolutions and corruption. Public Choice (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-024-01173-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-024-01173-1