Abstract

We present a model of plea bargaining and vary the value a prosecutor places on a conviction obtained via plea bargain relative to a conviction obtained at trial. We show that increasing the relative value of a plea bargain increases the trial penalty and decreases the severity of the equilibrium plea bargain. We report the results of an exploratory experiment which assesses this prediction in a more realistic setting, in which subjects are incentivized by conviction rates. Our treatment variable is whether convictions obtained via plea bargain are included in conviction rate calculations. Including plea bargains in conviction rates increases the number of plea offers made and increases the trial penalty, which is qualitatively in line with our predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is difficult to effectively study plea bargaining with naturally occurring criminal justice data. For instance, cases that are dropped or not pursued will not show up in trial or plea bargaining records. Likewise, it would be difficult, invasive, and expensive (and likely not even possible) to measure or obtain accurate data on evidence strength and case by case options prosecutors weigh when making their decisions. In our view, theory and experiments provide us with an opportunity to control many of these factors so that incentives and decisions can be cleanly explored.

Mueller (2003) defines choice as “the economic study of nonmarket decision making.”.

Joy and McMunigal (2011) acknowledge that such bonus schemes are not technically violations of the ABA’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct, though they argue for making prosecutor bonuses unethical.

In the literature, it is common to assume that prosecutors focus on convictions and conviction rates. Shamir and Shamir (2012) develop a model of court congestion built on the assumptions that prosecutors maximize either conviction rates or numbers of convictions, while Ferguson-Gilbert (2001) sets forth a general overview of why prosecutors seek to maximize conviction rates. Rasmusen et al. (2009) note that prosecutors often tout their conviction rates when running for elections, and media accounts provide examples of campaign battles over conviction rates (Dallas County DA 2010; Dujardin 2017; Rodricks 2022). There is theoretical and empirical evidence that when prosecutors are beholden to voters, elections can spur increases in the relative number of cases taken to trial relative to those resolved through plea bargaining (Bandyopadhyay and McCannon 2014; Dyke 2007). Gordon and Huber (2002) show that, when information about specific cases is limited, voters who care about Type I and II errors can best achieve their electoral goals by voting for prosecutors who successfully obtain convictions. Further, when prosecutors are not directly accountable to voters, institutional incentives nevertheless encourage them to maintain a high conviction rate (Bibas 2004; Zacharias 1991).

Importantly, note that if the prosecutor only cared about conviction, they could always obtain one by offering a sufficiently lenient plea offer. To ensure that our model is interesting, and to match the convention in the literature, we assume that the prosecutor also prefers a harsher sentence, all else equal.

Some of our sessions also involved law students at Baylor University’s law school, to further address the concern that a focus on conviction alone may not reflect prosecutor preferences.

A variety of proposals have been made with the intention of curbing guilty pleas by innocent defendants. Reinganum 1988 finds that restricting prosecutorial discretion such that they must offer uniform plea bargains for a given charge can improve welfare; the proposal works by limiting prosecutors’ ability to offer larger sentence differentials when cases against defendants are weaker. Another more extreme proposal is to abolish plea bargaining altogether (Schulhofer 1984). Others suggest screening cases prior to referring them to a prosecutor to ensure the available evidence meets a predefined threshold (Wright and Miller 2002). The purpose of such screening would be to allow prosecutors to bargain only with defendants who are more likely to be guilty.

Ever since Becker (1968), many studies have sought to explore the deterrence effect of policies and criminal justice procedures. Zeiler and Puccetti (2018) outlines many such theoretical models and experimental studies that have done so. Recent examples include Cuellar and Rentschler (2023a),Cuellar and Rentschler (2023b), Cuellar and Rentschler (2023c) and Cuellar (2023).

Adamson and Rentschler (2023) is a notable exception, although they focus on policing incentives, rather than prosecutors.

This probability function implicitly accounts for the distribution of evidence of innocence the defendant may present (which the prosecutor does not observe), and how that distribution of evidence may depend on the true guilt or innocence of the defendant.

Since, in practice, prosecutors almost always make a plea offer, this assumption is not particularly restrictive. If this assumption fails, the prosecutor would simply decline to plea bargain, and go directly to trial with a charge of \({c}_{t}^{*}\).

To see this, note that the payoff of plea bargaining is \(b{c}_{p}^{*}\), and the expected payoff of going to trial without plea bargaining is \(2p\left({c}_{t}^{*}\right){c}_{t}^{*}-{c}_{t}^{*}\). Since we assume that \(p\left({c}_{t}^{*}\right)\le 1/(2-b)\), the payoff the former exceeds that of the latter.

We conducted two seed sessions as well, which included both prosecutor and defendant participants that enabled us, along with the jury sessions, to pay the prosecutors in the current study using real participant decisions and standard non-deception techniques. These seed sessions are described in further detail in Sect. 3.3.

We will refer to the computer-generated claim that a crime has occurred as an “accusation.” We will refer to the decision by the prosecutor as a “charge.”.

For more details about the exact probabilities used to generate evidence of guilt and innocence the reader can see Figure SI1. Remember though, that participants did not receive this level of detail on the evidence generation process.

Note our study uses non-neutral language rather than a more standard neutral language approach. There are factors in the criminal justice realm that could affect decisions that we think would be lost were instructions neutral in language. A “sense of justice” or “responsibility” that comes when one is a prosecutor facing a theft situation would, for instance, be lost in a neutral language environment. Similarly, if defendants’ decisions were framed to prosecutors neutrally as “choice A” or “choice B” rather than as crimes or theft, then there would be no aspect of deservingness of punishment. It would be a bargaining environment still, but factors like inequality aversion, altruism, etc. may play very different roles in determining outcomes. We conclude that while a similar experiment could be designed using neutral language, that we could not generalize to the criminal justice system the results from such a study in as believable a manner.

See Sect. 3.3 below for a description of the seed experiments used to determine prosecutors’ payoffs in this experiment.

Note having our lab prosecutors know that their plea and trial decisions can affect real defendants is a critically important aspect of our study. “Real world” prosecutors face not only personal incentives ranging from salary, bonuses, promotions, and career advancements, but they know that their decisions affect real people and that they are partly responsible for ensuring that “justice” is served. We want that in our study as well, which we do when our prosecutors know their decisions can affect real people in the future. If this “sense of justice” is meaningful to people (in the lab or in the “real world”), it might affect prosecutors’ decisions and push them away from some behaviors that in some circumstance may be monetarily profit maximizing, like dropping all charges except where prosecutors have strong evidence of guilt.

After finishing the prosecutor game described here, all participants also participated as prosecutors in a second game identical to the game they played the first time, but where bonuses were paid out randomly rather than based upon the conviction rate (this game always occurred second). We do not discuss that data here. Participants were paid cash for one of the two games, randomly selected.

All tests reported are two-tailed Mann–Whitney tests, unless otherwise noted.

Table 4 in Appendix B contains summary statistics and the results of Mann–Whitney tests comparing the proportion of dropped cases for each possible combination of crime level and level of evidence.

Table 5 in Appendix B contains summary statistics and the results of Mann–Whitney tests comparing the proportion of cases that proceed directly to trial for each possible combination of crime level and level of evidence.

Table 6 in Appendix B breaks this result down by all possible crime and evidence levels.

Table 7 in Appendix B reports summary statistics and Mann–Whitney tests of this difference for each possible level of crime and evidence.

These costs may be particularly salient for poorer defendants who cannot afford bail/bond (and have to make plea bargain decisions from behind bars) or who rely upon public defenders or court-appointed attorneys for legal defense. Court-appointed attorneys are often paid a flat rate per case whether it is decided by plea or by trial, which may incentivize them to encourage clients to take plea bargains to reduce the time spent on the case. In contrast, an hourly-paid private defense attorney may prefer more time-consuming trials and therefore advise against plea bargains that are bad for the defendant. Indeed, many criminal defense attorneys handle both hourly and court-appointed cases, so any given attorney may face conflicting incentives across clients. See Agan et al. (2018) for a discussion of criminal defense lawyer incentives and citations to additional literature. Many additional factors, such as poverty, race, fear, gender, risk preferences, etc., could influence a person’s willingness to take a plea bargain, even though these factors are irrelevant to proving the elements of the charged crimes. Experimental studies show that bargaining behavior depends on individual risk preferences, on the stake size, and on the bargaining power the individual possesses (McCannon et al. 2016).

References

Adamson, J., & Rentschler, L. (2023). How policing incentives affect crime, measurement, and justice. Working Paper.

Agan, A., Freedman, M., & Owens, E. (2018). Is your lawyer a lemon? Incentives and selection in the public provision of criminal Defense. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(2), 294–309.

Aimone, J., Rentschler, L., & North, C. (2019). Priming the jury by asking for donations: An empirical and experimental study. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 160, 158–167.

Alschuler, A. W. (1979). Plea bargaining and its history. Columbia Law Review, 79, 1–43.

Balko, R. (2013). The untouchables: America’s misbehaving prosecutors, and the system that protects them. Huffington Post.

Bandyopadhyay, S., & McCannon, B. C. (2014). The effect of the election of prosecutors on criminal trials. Public Choice, 161, 141–156.

Barkai, J. L. (1977). Accuracy inquiries for all felony and misdemeanor pleas: Voluntary pleas but innocent defendants? University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 126, 88–146.

Barkow, R. E. (2009). Institutional design and the policing of prosecutors: Lessons from administrative law. Stanford Law Review, 61(4), 869–922.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach (pp. 13–68). The Economic Dimensions of Crime.

Bibas, S. (2004). Plea bargaining outside the shadow of trial. Harvard Law Review, 117, 2463–2547.

Charness, G., & DeAngelo, G. (2018). Law and economics in the laboratory. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Cook, D. L., Schlesinger, S. R., Bak, T. J., & William, T. (1995). Rule II. Criminal caseload in U.S. district courts: more than meets the eye. American University Law Review, 44, 1579–1598.

Cuellar, P., & Rentschler, L. (2023c). Plea bargaining with prosecutorial commitment. Working Paper.

Cuellar, P. (2023). Voluntary disclosure of evidence in plea bargaining. Working Paper.

Cuellar, P., & Rentschler, L. (2023b). Adversarial Bargaining with Exogenous Shocks. Working Paper.

Cuellar, P., & Rentschler, L. (2023a). Threat, commitment, and brinkmanship in adversarial bargaining. Working Paper.

Dallas County DA touts conviction rate that includes guilty pleas. (2010). Dallas Morning News.

Dujardin, P. (2017). Hampton prosecutor, challenger spar over conviction rate reports. Daily Press.

Dyke, A. (2007). Electoral cycles in the administration of criminal justice. Public Choice, 133, 417–437.

Fender, J. (2011). DA Chambers offers bonuses for prosecutors who hit conviction targets. Denver Post.

Ferguson-Gilbert, C. (2001). It is not whether you win or lose, it is how you play the game: Is the win-loss scorekeeping mentality doing justice for prosecutors? California Western Law Review, 38, 283.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics.

Gordon, S. C., & Huber, G. A. (2002). The effect of electoral competitiveness on incumbent behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 334–351.

Joy, P. A., & McMunigal, K. C. (2011). Contingent rewards for prosecutors? Criminal Justice, 26(3), 55–58.

Leonetti, C. (2012). When the emperor has no clothes III: Personnel policies and conflicts of interest in prosecutors’ offices. Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, 22(1), 53–92.

McCannon, B. C., Asaad, C. T., & Wilson, M. (2016). Financial competence, overconfidence, and trusting investments: Results from an experiment. Journal of Economics and Finance, 40, 590–606.

Mueller, D. (2003). Public choice III. Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, B. J., & Hanson, R. A. (1999). Efficiency, timeliness, and quality: A new perspective from nine state criminal courts. National Center for State Courts.

Ralston, J., Aimone, J., Rentschler L., & North, C. (2019). False confessions: An experimental laboratory study of the innocence problem. Working Paper.

Rasmusen, E., Raghav, M., & Ramseyer, M. (2009). Convictions versus conviction rates: The prosecutor’s choice. American Law and Economics Review, 11(1), 47–78.

Reinganum, J. F. (1988). Plea bargaining and prosecutorial discretion. American Economic Review, 78(4), 713–728.

Rodricks, D. (2022). Marilyn Mosby claim as an effective prosecutor a hard case to make as Baltimore violence continues. Baltimore Sun.

Schulhofer, S. J. (1984). Is plea bargaining inevitable? Harvard Law Review, 97, 1037–1107.

Shamir, J., & Shamir, N. (2012). The role of prosecutor’s incentives in creating congestion in criminal courts. Review of Law and Economics, 8(3), 579–618.

Silverglate, H. (2011). The revolving door at the department of justice. Forbes.

Sipes, D. A., Oram, M. E., Thornton, M. A., Valluzzi, D. J., & van Duizend, R. (1988). On trial: The length of civil and criminal trials. Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts.

Smith, V. (1982). Microeconomic systems as an experimental science. American Economic Review, 72(5), 923–955.

Stroud A. M. (2015). Lead prosecutor apologizes for role in sending man to death row. Shreveport Times.

The Cost of Justice. (1998). Los Angeles Times.

Wright, R., & Miller, M. (2002). The screening/bargaining tradeoff. Stanford Law Review, 55(1), 29–118.

Zacharias, F. C. (1991). Structuring the ethics of prosecutorial trial practice: Can prosecutors do justice? Vanderbilt Law Review, 44(1), 45–114.

Zeiler, K., & Puccetti, E. (2018). Crime, punishment, and legal error: A review of the experimental literature. Boston University School of Law, Law and Economics Research Paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Charles Koch Foundation for generous funding. For helpful comments and discussions, we thank seminar participants at the 2018 Southern Economic Association meetings and Greg DeAngelo, Bryan McCannon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A: Experimental instructions

We include sample instructions used in a typical experimental session. The particular instructions included are those used for sessions run with law students using accepted guilty pleas and guilty verdicts in the calculation of the conviction rate. In a session where only guilty verdicts were used to calculate the conviction rate, the instructions would have clearly stated so.

The only within experiment differences between law student and undergraduate student instructions were the rewards for performance. Instead of being rewarded with $25 for obtaining the highest conviction rate in a group, undergraduates were rewarded with $10. Similarly, a second place finish was rewarded with $7.5 instead of $15.

Group sizes were variable, starting at 3 at a minimum and being as large as 5. The size depended on how many participants showed up for a particular session. Again, the language used in the instructions would change to specify the correct group size.

Instructions

Thank you for participating in today’s experiment. You will receive a $5 payment for coming to the lab today. In addition, you will be paid $15 for participating and completing today’s experiment. You may also obtain an additional bonus of either $25 or $15.

You will be in the role of a prosecutor in today’s experiment. You are in a group of participants who all have this role. One of your group will receive the bonus of $25, and another participant in your group will receive the bonus of $15.

Your decisions will be used, together with the decisions of other participants in the same role as you, to determine outcomes for participants in a separate set of future experiments.

The nature of the future experiments, which will be explained to you in detail in a few moments, will involve situations in which participants have the opportunity to take money (real US$) which does not belong to them from another participant (from now on, we will refer to this as a theft).

You will provide decisions that determine the monetary punishment, if any, for a participant who has been accused of a theft (from now on, we will refer to a participant who has been accused as a defendant).

Each scenario for which you will provide decisions will involve a defendant. You will have some level of evidence of his or her guilt. The defendant may also have evidence of his or her innocence.

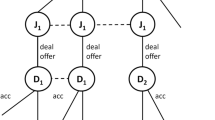

You will decide whether to drop the charges against the defendant or to prosecute the defendant. If you decide to prosecute the defendant you will determine the severity of the charge as well as the possible monetary punishments he or she would face if found guilty. You will also be able to offer a plea bargain. A plea bargain is a charge and a level of monetary punishment that is offered to the defendant if he or she pleads guilty.

If the accused participant decides to plead not-guilty when charged with a theft, there is a trial. In a trial, the evidence of guilt you have, as well as any evidence of innocence the defendant provides, will result in either a guilty or not-guilty finding. The decisions of participants in the role of jurors will be used to make such findings. Participants in the role of jurors have been instructed to make a finding of guilty only if the evidence presented proves guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Please take these tasks seriously as real people will be affected by your decisions.

As mentioned earlier you will be paid in cash for your decisions as a prosecutor today. After you finish making your decisions we will ask you to fill out a short survey and you will be paid in cash as you leave the lab.

The decisions you make today will be used in the event that a participant in a future experiment is accused of a theft in the exact manner described to you today. That is, your decisions will only be used in the exact situations that you will evaluate in this experiment.

In this future experiment, $10 will be divided between two participants who are partners. The computer will randomly choose a division of the $10 which allocates a portion of the money to each of the two participants. This preset division is revealed to one of the participants. This participant then must report the preset division chosen by the computer. The division reported by the participant will be implemented. However this participant can choose to take some of the money that is supposed to go to his or her partner by misrepresenting the preset division chosen by the computer.

After the participant reports the division of money (which may or may not correspond to the preset division chosen by the computer) the computer will generate either evidence of a theft or no evidence of a theft. If there is evidence of a theft, the computer will make an accusation. An accusation can be of a SMALL theft (a theft between $0.10 and $1.00), a MEDIUM theft (a theft between $1.10 and $2.00) or a LARGE theft (a theft between $2.10 and $3.00).

Note that an accusation may or may not be true. While a defendant will know for certain whether or not they are guilty of a theft, neither the prosecutor nor the jurors know for certain.

The computer is more likely to make an accusation if the defendant is truly guilty. In particular, 70% of truly guilty defendants will receive an accusation, and 30% of truly innocent defendants will receive an accusation.

If the computer makes an accusation, then there is some evidence of guilt to support this accusation. This evidence of guilt can be WEAK, MEDIUM or STRONG.

As the names suggest, STRONG evidence is harder to get (and implies there is more evidence of guilt) than MEDIUM evidence. MEDIUM evidence is harder to get (and implies there is more evidence of guilt) than WEAK evidence. For each of these three levels, a prosecutor is always more likely to get a particular level of evidence of guilt if the defendant is truly guilty compared to a truly innocent defendant.

If the computer makes an accusation, then the defendant may or may not have some evidence of innocence. Evidence of innocence can be WEAK, MEDIUM or STRONG. As the names suggest, STRONG evidence is harder to get (and implies there is more evidence of innocence) than MEDIUM evidence. MEDIUM evidence is harder to get (and implies there is more evidence of innocence) than WEAK evidence. For each of these three levels, a defendant is always more likely to get a particular level of evidence of innocence if the defendant is truly innocent compared to a truly guilty defendant.

A truly guilty defendant will have no evidence of innocence 70% of the time (note that this means that a truly guilty defendant will have some evidence of innocence 30% of the time). A truly innocent defendant will have some evidence of innocence 80% of the time (so that a truly innocent defendant will have no evidence of innocence 20% of the time).

This information is summarized in the tables below.

If, after an accusation, a defendant goes to trial for a given level of theft (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE) then the evidence of guilt available to support that charge (WEAK, MEDIUM or STRONG), as well as any evidence of innocence the defendant decides to provide (WEAK, MEDIUM or STRONG) is shown to three jurors. These jurors independently evaluate all evidence presented, and are instructed to make a recommendation of a guilty finding only if they are convinced of the defendant’s guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Jurors are told that: “Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is proof of such a convincing character that you would be willing to rely and act upon it without hesitation in making the most important decisions of your own affairs.” If all three juror recommendations are the same, then the unanimous decision determines whether the defendant is found guilty (if all three jurors chose “Guilty”) or not-guilty (if all three jurors chose “Not-Guilty”). If all three jurors’ decisions are not the same, then the trial is called a “mistrial” and the computer will randomly select another alternative set of three jurors. This process continues until the first time the decisions of all three selected juror decisions match.

In an earlier experiment, jurors have already made recommendations regarding guilty findings in all the possible trials that could arise in today’s experiment. It is the decisions from this earlier experiment that will be used to determine the outcome of trials in today’s experiment.

If, after an accusation, a defendant is found guilty, then a monetary punishment is subtracted from his or her earnings in the experiment. This monetary punishment is higher for larger thefts. For each level of thefts, there is a low interval of possible punishments, and a high interval of possible punishments. The possible punishments for each level of theft are summarized in the table below.

Low interval of possible punishment | High interval of possible punishment | |

|---|---|---|

SMALL theft | $0.10–$0.30 | $0.40–$0.60 |

MEDIUM theft | $0.60–$0.80 | $0.90–$1.10 |

LARGE theft | $1.10–$1.30 | $1.40–$1.60 |

If a defendant is accused of a certain level of theft, and there is a given level of evidence of guilt to support this accusation, the defendant may be charged with a different level of theft. If a defendant is charged with level of theft that is different than the initial accusation, then the evidence of guilt in support of this different theft is reduced accordingly.

For example, suppose a defendant is accused of a SMALL theft, and there is STRONG evidence of guilt in support of this accusation. This defendant could be charged with a MEDIUM theft, and there would be MEDIUM evidence of guilt to support this charge. This defendant could also be charged with a LARGE theft, and there would be WEAK evidence of guilt in support of this charge.

If a defendant is accused of a SMALL theft, and there is MEDIUM evidence of guilt in support of this accusation, this defendant could be charged with a MEDIUM theft, and there would be WEAK evidence of guilt to support this charge. However, this defendant could not be charged with a LARGE theft, because there is insufficient evidence of guilt to support this charge.

If a defendant is accused of a SMALL theft, and there is WEAK evidence of guilt in support of this accusation, then this defendant cannot be charged with any other level of theft. This is because there is insufficient evidence of guilt to support any other charge.

To provide another example, suppose a defendant is accused of a MEDIUM theft, and there is STRONG evidence of guilt in support of this accusation. This defendant could be charged with a LARGE theft, and there would be MEDIUM evidence of guilt to support this charge. This defendant could also be charged with a SMALL theft, and there would be STRONG evidence of guilt in support of this charge (there is no higher level of evidence of guilt than STRONG).

If a defendant is accused of a MEDIUM theft, and there is MEDIUM evidence of guilt in support of this accusation, this defendant could be charged with a SMALL theft, and there would be STRONG evidence of guilt to support this charge. This defendant could also be charged with a LARGE theft, and there is WEAK evidence of guilt to support this charge.

If a defendant is accused of a MEDIUM theft, and there is WEAK evidence of guilt in support of this accusation, then this defendant could be charged with a SMALL theft, and there is MEDIUM evidence of guilt to support this charge. However, this defendant cannot be charged with a LARGE theft, because there is insufficient evidence to support the charge.

Lastly, suppose a defendant is accused of a LARGE theft, and there is STRONG evidence of guilt in support of this accusation. This defendant could be charged with either a SMALL or MEDIUM theft, and there would be STRONG evidence of guilt to support either of these charges (there is no higher level of evidence of guilt than STRONG).

Similarly, if a defendant is accused of a LARGE theft, and there is MEDIUM evidence of guilt in support of this accusation, this defendant could be charged with either a SMALL or MEDIUM theft, and there would be STRONG evidence of guilt to support either of these charges.

If a defendant is accused of a LARGE theft, and there is WEAK evidence of guilt in support of this accusation, then this defendant could be charged with a MEDIUM theft, and there would be MEDIUM evidence of guilt to support the charge. This defendant could also be charged with a SMALL theft, and there would be STRONG evidence of guilt to support this charge.

It is important to note that if a defendant is charged with a level of theft that differs from the initial accusation, then his or her level of evidence of innocence also adjusts accordingly.

For example, suppose a defendant is accused of a SMALL theft, and has STRONG evidence of innocence against this accusation. If he or she were charged with either a MEDIUM or LARGE theft, there would be STRONG evidence of innocence against either of these charges.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a SMALL theft, and has MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this accusation. If he or she were charged with either a MEDIUM or LARGE theft, there would be STRONG evidence of innocence against either of these charges.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a SMALL theft, and there is WEAK evidence of innocence against this accusation. If the defendant were charged with a MEDIUM theft, then there would be MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with a LARGE theft, there would be STRONG evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a SMALL theft, and there is NO evidence of innocence against this accusation. If the defendant were charged with a MEDIUM theft, then there would be WEAK evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with a LARGE theft, there would be MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a MEDIUM theft, and there is STRONG evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with a LARGE theft, there would be STRONG evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with a SMALL theft, there would be MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a MEDIUM theft, and there is MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with a SMALL theft, and there would be WEAK evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with a LARGE theft, there would be STRONG evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a MEDIUM theft, and there is WEAK evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with a SMALL theft, there would be NO evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with LARGE theft, there would be MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a MEDIUM theft, and there is NO evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with a SMALL theft, there would be NO evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with LARGE theft, there would be WEAK evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a LARGE theft, and there is STRONG evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with a MEDIUM theft, there would be MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with a SMALL theft, there would be WEAK evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a LARGE theft, and there is MEDIUM evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with a MEDIUM theft, there would be WEAK evidence of innocence against this charge. If this defendant were charged with a SMALL theft, there would be NO evidence of innocence against this charge.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a LARGE theft, and there is WEAK evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with either a MEDIUM or SMALL theft, there would be NO evidence of innocence against either of these charges.

Suppose a defendant is accused of a LARGE theft, and there is NO evidence of innocence against this accusation. If this defendant were charged with either a MEDIUM or SMALL theft, there would be NO evidence of innocence against either of these charges.

When a participant in the future experiment is accused of a theft (either SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE), we will use your decisions today to determine what monetary punishment, if any, they will face.

Acting in the role of a prosecutor, you will observe two pieces of information before you make any decisions: the accused level of theft (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE) and the level of evidence of guilt in support of the accusation. Remember that you will not know for certain if the defendant is guilty or not. You will not know the level of evidence of innocence, if any, that the defendant has at the time that you make your decisions. However, the defendant will be aware of the level of evidence of guilt that you, as the prosecutor have. Defendants may also choose to exercise their right to not testify on their own behalf. Note: all jurors were instructed that:

“A defendant has the option to make their evidence of innocence available or not. This right to not “testify” is guaranteed by the United States Constitution and should not be taken as implying guilt.”

After observing the accused level of theft (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE) and the level of evidence of guilt in support of the accusation, you will decide between three options:

-

Drop the charge In this case, there is no trial, and the defendant does not face any monetary punishment.

-

Proceed to trial without offering a plea bargain In this option, you choose a level of theft to charge the defendant with (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE theft). In addition, you will choose whether the defendant will pay a monetary punishment from the low interval or the high interval corresponding to the level of theft you are charging him or her with. Of course, the defendant will not pay any monetary penalty if he or she is found not-guilty by the jury. Also, remember that if the charge differs from the accusation, then that the evidence of guilt and the (unobserved) evidence of innocence is adjusted accordingly.

-

Offer a plea bargain A plea bargain is an offer that you make to a defendant in order to avoid a trial. It consists of a charge (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE theft) and associated monetary punishment that you are willing to offer to the defendant in exchange for a guilty plea. If you choose to offer a plea bargain you also choose a charge (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE theft) and associated interval of monetary punishment that you will take to trial if the defendant does not accept your offered plea bargain. When choosing these things, you cannot opt for a plea bargain that compares unfavorably with the charge and interval of punishment that go to trial if the plea bargain is rejected.

You will make decisions in every possible scenario a prosecutor could face. Since there are three possible levels of theft, and three possible levels of evidence of guilt, that means you will make decisions in nine different scenarios.

After you have made decisions in each of the nine scenarios, you will go through all nine scenarios for a second time. We will refer to first set of decisions as cycle one, and the second set of decisions (in the same nine scenarios) as cycle two. At the end of the experiment one of these two cycles will be chosen to determine payments.

We will use your decisions today to determine outcomes in future experiments. To help determine payments in today’s experiment we will use the decisions of participants in the roles of defendants and jurors collected in a past experiment. We will compare your decisions with instances in which past defendants made decisions for when they were accused of a theft (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE), there was some evidence of guilt in support of the accusation (WEAK, MEDIUM or STRONG), and there was either no evidence of innocence or the level of evidence of innocence was WEAK, MEDIUM or STRONG.

We will use your decisions in that exact scenario to determine what the outcome would have been if you had been matched with this past defendant. If there would be a trial, the decisions of jurors from past experiments will be used to determine whether or not the trial results in a finding of guilty or not-guilty.

We will match your decisions in cycle one with one hundred instances in which past defendants have been accused, and determine the outcome as described above. We will then match your decisions in cycle two against these same one hundred instances.

For each of these two cycles, we will calculate your conviction rate, which is the percentage of instances in which you opted to charge a defendant with a crime, and there was a guilty finding. A guilty finding occurs when a defendant pleads guilty or is found guilty in a trial. Note that accepted plea bargains are included in the calculation of this conviction rate.

If cycle one is randomly chosen for payment, then the $25 bonus goes to the prosecutor (in your group of 3) who had the highest conviction rate. The bonus of $15 goes to the prosecutor (in your group of 3) who had the second highest conviction rate. The remaining prosecutor in your group do not get a bonus.

If cycle two is randomly chosen for payment, then the recipients of the $25 bonus and the $15 bonus (among your group of 3) is determined randomly, with each person in your group of 3 having an equal probability of receiving either bonus. No one person can receive both bonuses.

Before you make decisions in cycle one, we will also ask you to tell us how likely a prosecutor is to obtain a verdict of guilty at trial in several situations. Your answers to these questions will not affect your payoffs in any way.

Summary

-

1.

In today’s experiment you will be in the role of a prosecutor.

-

2.

You will be asked to make decisions in nine scenarios. In a given scenario you will observe two pieces of information: the level of theft a defendant is accused of (SMALL, MEDIUM or LARGE), and the level of evidence of guilt to support that accusation (WEAK, MEDIUM or STRONG).

-

3.

You will choose to either: (1) drop the charge, (2) proceed to trial without offering a plea bargain, (3) offer a plea bargain.

-

4.

The decisions of the prosecutors, in today’s experiment, will be used, in future experiments to affect the real monetary pay of real participants who are the role of defendants in those future experiments.

-

5.

Your decisions as a prosecutor will be matched with the decisions of real participants of past experiments in the roles of defendants and jurors to determine the outcomes of accusations. We will compare your decisions with those of defendants in 100 accusations.

-

6.

You will provide decisions for all nine scenarios twice. The first time you provide answers is cycle one. The second time you provide answers is cycle two.

-

7.

For each of these two cycles, we will calculate your conviction rate, which is the percentage of instances in which you opted to charge a defendant with a crime, and there was a guilty finding. A guilty finding occurs when a defendant pleads guilty or is found guilty in a trial. Note that accepted plea bargains are included in the calculation of this conviction rate.

-

8.

If cycle one is randomly chosen for payment, then the $25 bonus goes to the prosecutor (in your group of 3) who had the highest conviction rate. The bonus of $15 goes to the prosecutor (in your group of 3) who had the second highest conviction rate. The remaining prosecutor in your group does not get a bonus. If cycle two is randomly chosen for payment, then the recipients of the $25 bonus and the $15 bonus (among your group of 3) is determined randomly, with each person in your group of 3 having an equal probability of receiving either bonus. No one person can receive both bonuses.

Appendix B

7,

8 and

9.

Appendix C

See Figs.

6 and

7.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ralston, J., Aimone, J., Rentschler, L. et al. Prosecutor plea bargaining and conviction rate structure: evidence from an experiment. Public Choice 196, 299–329 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01081-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01081-w