Abstract

We present a simple model, illustrating how democracy may improve the quality of the economic institutions. The model further suggests that institutional quality varies more across autocracies than across democracy and that the positive effect of democracies on economic institutional quality increases in people’s human capital. Using a panel data set that covers 150 countries and the period from 1920 to 2019, and different measures of economic institutional quality, we show results from fixed effect and instrumental variable regressions that are in line with the predictions of our model.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Both in economics and in political science, it is widely acknowledged that institutions play a key role in explaining cross-country differences in economic development.Footnote 1 An open question is, however, which factors influence the emergence of growth-enhancing institutions. We address this issue by examining whether the quality of the economic institutions is determined by the political regime. More specifically, we study whether transitions from autocracy to democracy cause improvements in economic institutional quality.Footnote 2

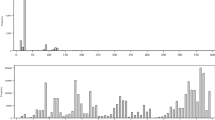

We start from the simple observation that the quality of the economic institutions positively correlates with the level of democracy. Figure 1 shows this stylized fact for four particular years (1920, 1950, 1980, 2010), using a continuous democracy index and an expert-based measure of private property protection. Economic theory provides two explanations for the correlation presented in Fig. 1. The first is that democratization requires well-functioning economic institutions (see Friedman, 1962; Hayek, 1944). An alternative explanation is that democratic governments have a greater interest in good economic institutions than autocratic governments (see Przeworski and Limongi, 1993; Olson, 1993).

In this paper, we elaborate on the latter argument and present a simple theoretical model to explain why economic institutional quality might increase after a democratic transition. Our model considers a society that consists of two groups: the elite and the people. Agents belong to only one group and the elite constitutes the minority of the population. Members of the elite derive utility from consumption which is financed via expropriation, whereas the people enjoy consumption and leisure, engage in commercial activities, and face an expropriation risk. The elite and people inform the government regarding their preferred level of institutional quality. The elite desires some room for expropriation, while the people want to have economic institutions that protect them. Our model implies that democracy has a positive effect on the quality of the economic institutions because under a democratic system governments care more about people’s preferences.

Figure 1 also shows that the cross-country differences in the quality of the economic institutions are larger among the autocracies than among the democracies. Our model reflects this pattern. In particular, our model suggests that an autocratic government implements worse economic institutions if the people command a high level of human capital. The logic behind this prediction is as follows. The elite wants that the people engage in commercial rather than leisure activities because people’s allocation of time influences elite’s possibilities for expropriation. Because human capital is productivity- enhancing, well educated people engage in commercial activities even if they are only weakly protected against expropriations. By contrast, the poorly educated people need greater incentives. Good economic institutions constitute such an incentive since they ensure that the people keep a relatively large share of their revenues.

Democracy and economic institutional quality (raw data). Notes The figures show the correlation between democracy and economic institutional quality for the years 1920, 1950, 1980, and 2010. We use an expert-based indicator on private property protection from V-Dem to measure the quality of the economic institutions and the Machine Learning index by Gründler and Krieger (2021) to measure democracy

We use a panel data set, covering 150 countries and the period from 1920 to 2019, different measures of democracy and economic institutional quality, and two empirical strategies to study the accuracy of our model. Our focus is on two predictions: (i) the quality of the economic institutions improves after a full transition from autocracy to democracy, and (ii) the effect of democracy on institutional quality is increasing in the level of human capital. The findings of our regression analyses are in line with these predictions.

We contribute to the literature that studies the relationship between democracy and institutional quality.Footnote 3 The major difference between previous empirical studies and our analysis is the length of the examination period: while previous studies use data from 1970/80 onward, our examination period starts in 1920. Furthermore, we apply a two-stage least squares approach to confirm that democracy positively affects institutional quality, whereas previous studies rely on OLS and GMM methods.

Only a few studies examine whether the effect of democracy on institutional quality depends on other socioeconomic factors. Acemoglu and Robinson (2006, 2008) develop a model suggesting that a high level of income inequality erodes the positive effect of democracy on institutional quality. Sunde et al. (2008), Krieger and Meierrieks (2016), and Kotschy and Sunde (2017) offer empirical evidence that confirms this prediction. Fortunato and Panizza (2015) find that the link between democracy and institutional quality depends on the level of human capital. Their analysis differs from our analysis for three reasons: first, we use a much larger dataset; second, we address endogeneity issues with an instrumental variable approach; and finally, we explain the positive effect of the interaction between democracy and human capital on institutional quality with differences between autocratic regimes rather than with differences between democratic regimes. Fortunato and Panizza (2015) suggest in particular that education improves voters’ ability to select competent leaders and that these competent leaders implement better economic institutions. We update the database by Besley and Reynal-Querol (2011) to study whether the mechanism suggested by Fortunato and Panizza (2015) applies. Our results do not support the hypothesis that higher ability of politicians explains why the positive effect of democracy on institutional quality depends positively on the level of human capital.

We structure this paper as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce the theoretical model. In Sect. 3, we present the data, the identification strategy, and the empirical results. Section 4 concludes.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Basic setting

Following Acemoglu and Robinson (2001, 2005), we study a society consisting of two groups of citizens: the people (P) and the elite (E).Footnote 4 Agents belong to only one of the groups and the people constitute the majority of the society. We also assume that the members of a specific group are identical.Footnote 5 Consequently, we can interchangeably speak about the entire group and a representative agent. All individuals are risk neutral and population size is normalized to 1.

2.1.1 Government

Both the people and the elite inform the government regarding their preferred level of economic institutional quality. The government uses this information to set the actual level of economic institutional quality (\(\rho\)):Footnote 6

where \(\rho ^{E} \in [0,1]\) denotes the level of institutional quality indicated by the elite and \(\rho ^{P} \in [0,1]\) the level of institutional quality indicated by the people. The exogenously given weighting parameter \(\delta \in [0,1]\) reflects the extent to which the government takes the preferences of the people into account when choosing the quality of the economic institutions. Below, we interpret \(\delta\) as the degree of democratization since the people constitute the majority of the population. We refer to a regime as democratic if \(\delta \approx 1\) and as autocratic if \(\delta \approx 0\).

2.1.2 People

Similar to the model by Besley and Ghatak (2010), we suppose that the people use a fraction of their time \(z^{P} \in [0,1]\) for commercial activities and the rest of their time \(l^{P} = 1 - z^{P}\) for leisure. For their commercial activities, people receive income (\(y^P\)) which increases in their working hours and their productivity. People’s productivity is determined by their human capital (h). Assuming a standard Cobb-Douglas function, people’s income is then:

where \(\alpha\) denotes an elasticity parameter. In a similar way, people derive utility from leisure activities:

where \(\gamma\) is another elasticity parameter. For mathematical convenience, we set \(\gamma =\) \(\sigma = 0.5\). Finally, the people lose some their income when the economic institutions are imperfect. Below, we refer to this loss risk as “expropriation” risk. The share of income that people lose due to expropriation is \(\lambda = 1 - \rho\). All income that is not expropriated will be used for private consumption (\(c^P\)).Footnote 7

People choose \(z^P\) to maximize the utility function:Footnote 8

where \(\beta > 0\) denotes a weighting parameter that reflects the intensity of the leisure preferences relative to consumption. The first-order condition implies

From Eqs. (4 and 5), we then obtain:

2.1.3 Elite

The members of the elite derive utility from private consumption which is completely financed via expropriation and face a revolution constraint. In line with Acemoglu and Robinson (2001), we assume that the elite loses its income if a revolt takes place. The probability of revolution \(\big ( \alpha \big )\) depends on the quality of the economic institutions:

where \(\theta \ge 0\) captures cultural and environmental factors affecting the likelihood of a revolution. The expected utility of the elite is thus given by:

2.2 Theoretical results

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the main predictions of our model. The solid line shows the quality of the economic institutions (\(\rho\)) that the government chooses, depending on the degree of democratization (\(\delta\)). The dashed (dotted) line shows the level of institutional quality that the members of the elite (people) indicate when informing the government regarding their preferences.

From Eqs. (6 and 9) follows that the people wish economic institutions that fully protect them against expropriation, whereas the elite prefers economic institutions that give room for expropriation:

The logic behind these results is as follows. The elite wants to expropriate because it finances its consumption through expropriation and loses its income source when the government prohibits any expropriation. By contrast, the people engage in commercial activities to finance their consumption. The greater the expropriation risk, the lower is the share of income that they can keep for themselves.

The level of institutional quality that the elite indicates to the government (\(\rho ^E\)) is depending on the degree of democratization. In an autocratic regime, the government only gives attention to the preferences of the elite. The members of the elite use this influence and indicate the institutional quality that maximizes their utility. When the people have some influence on the decisions of the government (\(\delta > 0\)), the elite will adjust the preference that it indicates to government in order to offset people’s demand for better economic institution.

A transition from a fully authoritarian regime to a fully democratic regime increases institutional quality. This prediction arises because the people prefer better economic institutions than the elite and because the influence of the people on the government increases in the process of democratization. However, a partial democratization is not necessarily associated with increasing institutional quality. The reason is that the elite adjusts its behavior, thus preventing changes in the quality of the economic institutions as long as the degree of democratization is relatively low \(\big ( \delta < {\bar{\delta }} \big )\).

Finally, our model predicts that the elite prefers weaker economic institutions if the people command a high level of human capital:

The explanation for this result is simple. The elite wishes that the people engage in commercial activities: the more commercial activities, the greater the possibilities for expropriation. Equation (5) implies that the time that the people devote to the commercial activities increases in both their human capital and the institutional quality:

In addition, human capital has a positive effect on people’s productivity:

Consequently, if the members of the elite want that people with a low level of human capital produce a similar output as people with a higher level of human capital, some additional incentives for engaging in commercial activities need to be provided for the people that command a low level of human capital. Protecting them (relatively well) against expropriation is such an incentive since people spend more time on commercial activities if the quality of the economic institution increases:

Put differently, our model creates the testable prediction that the positive effect of a democratization on institutional quality grows in the level of human capital. Figure 3 illustrates this prediction. If human capital is low (\(h = h_1\)), the economic institutions improve by \(\rho ^{P^*} - \rho ^{E^*}(h_1)\) after a transition from a fully autocratic regime to a fully democratic regime. For a higher level of human capital (\(h = h_2\)), this change is larger (\(\rho ^{P^*} - \rho ^{E^*}(h_2)\)).

2.3 Discussion

Our model predicts that a transition from autocracy towards democracy improves the quality of the economic institutions (Fig. 2) and suggests that the positive effect of democracy on institutional quality increases with increasing human capital (Fig. 3). Section 3 presents empirical results that confirm these two predictions. However, before we turn to our empirical analysis, we comment on some aspects of our model.

2.3.1 Effect heterogeneity

Our strong focus on the role of human capital may give rise to the impression that we downplay other factors that may also cause heterogeneity in the effect of democracy on institutional quality. We argue that this concern is unfounded since our simple model suggests other sources of effect heterogeneity. In particular, the model predicts that the elite makes more concessions to the people when the threat of revolution is high. We can also invoke cultural effects by assuming that the leisure preference \(\big ( \beta \big )\) depends on cultural traits. We move these factors to the background to focus on the predictions that are subject to the empirical testing.

2.3.2 Differences in institutional quality in democracies

Figure 1 shows that the citizens of some democratic countries are not fully protected against expropriation. Our model does not explain this fact. Acemoglu and Robinson (2006, 2008) present a model that suggests conditions under which a transition from autocracy to democracy does not improve institutional quality. A key feature of their model is that political power has a de facto and a de jure component. Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) explain that the degree of democratization is the de jure component, whereas cultural, economic, and geographical factors determine the de facto component. We can incorporate this distinction in our model by assuming that the government uses the following rule to set the quality of the economic institutions:

where \(\gamma \in (0,1)\) reflects the de facto power of the people. Figure 4 shows that this extension suffices to predict institutional differences between democracies.

2.3.3 Institutional persistence

Our model predicts that a partial democratization does not necessarily induce a change in institutional quality. Acemoglu and Robinson (2006, 2008) reach the same conclusion, using a model of endogenous political transitions. Our explanation for the institutional persistence differs (slightly) from their explanation. In our model, the elite adjusts the preference that it indicates to the government and can thereby completely offset people’s demand for better institutions if the degree of democratization is low. Acemoglu and Robinson (2006, 2008) argue, by contrast, that the elite sticks to its political views but increases its lobbying effort to compensate the loss in political influence caused by the democratization.Footnote 9

2.3.4 Human capital as exogenous factor

Another concern may be that the level of human capital is an exogenous factor in our model. This objection is not far-fetched given that various empirical studies report a positive effect of democracy on human capital (Baum and Lake, 2003; Fujiwara, 2015; Stasavage, 2005). We still think that the model assumption is plausible in our context because the purpose of our model is to illustrate the short-run consequences of political transitions for institutional quality and one potential source of effect heterogeneity. We argue that focusing on immediate effects is adequate since Méon and Sekkat (2022) and Rode and Gwartney (2012) suggest that most of the changes in economic institutions occur within the first few years after a political transition. Since the level of human capital changes relatively slowly, we can treat it as exogenous factor in our model.

2.3.5 Human capital and the threat of revolution

In our model, the level of human capital only affects the productivity of the people. Another factor that may depend on human capital is the probability of revolution. An argument may be that educated people can better organize a revolt and that thus the probability of revolution increases in the level of human capital. When extending the model in this direction, the result that the positive effect of democracy on institutional quality increases in the human capital of the people does no longer hold because human capital then affects the preferences of the elite in two opposing ways. For the sake of convenience, the basic model focuses one channel. Our empirical findings (see Sect. 3) imply that the channel sketched by the basic model (see Sect. 2.2) is dominating the opposing channel explained in this section.

3 Empirical analysis

3.1 Data

3.1.1 Democracy

How to measure democracy belongs undoubtedly to the most controversially discussed questions in the fields of political science and political economy. It is therefore hardly surprising that the literature provides a large number of democracy indices. A recent review article by Gründler and Krieger (2021) lists about a dozen measures that are regularly applied in studies on the causes and consequences of political change. These measures differ from each other in several manners, for instance with regard to their underlying concepts, their aggregation rules, their numerical forms, and their coverage rates. To determine which of the indices discussed by Gründler and Krieger (2021) is most appropriate for our purpose, we proceed as follows. In the first step, we exclude indicators with a broad definition of democracy to avoid conceptual overlaps with the measures that we use to quantify the quality of the economic institutions (see Sect. 3.1.2). The indicators whose underlying concepts are too broad to be suitable for our study are the Freedom House indices, the Unified Democracy Score by Pemstein et al. (2010), the Polity index, and the binary measure by Acemoglu et al. (2019). We also decide against the Democracy-Dictatorship index (see Bjørnskov and Rode, 2020) since Knutsen and Wig (2015) illustrate that this indicator creates biased regression results because of its underlying concept.

After having excluded some indicators for conceptual reasons, we are left with five potential measures of democracy. Our list includes the binary measure by Boix et al. (2013), V’Dem’s Polyarchy indicator (see Teorell et al., 2019), the continuous and the dichotomous Machine Learning index (see Gründler and Krieger, 2016; 2021), and the Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (see Skaaning et al., 2015). For two reasons, we select the continuous Machine Learning index as our primary measure. First, a recent study by Gründler and Krieger (2022) suggests that continuous indicators outperform dichotomous indicators due of their greater discriminating power. Second, the Machine Learning technique proposed by Gründler and Krieger (2016, 2021) is the aggregation method that is least likely to produce biased index values for regimes at the upper and lower end of the autocracy-democracy spectrum. Such biases are problematic as they trigger upward-biased estimates in OLS and 2SLS analyses on the economic effects of transitions towards democracy (Gründler and Krieger, 2022).

The continuous Machine Learning index varies between 0 (highly autocratic) and 1 (highly democratic). The underlying concept of democracy includes three dimensions: political participation, political competition, and freedom of speech.Footnote 10 To operationalize this definition, Gründler and Krieger (2021) exploit subjective and objective measures. Objective regime characteristics are (e.g.) the vote share of the leading party and the share of adult citizens who enjoy voting rights. The list of expert-based characteristics includes (e.g.) an index of party pluralism. The latest version of the Machine Learning indicator is available for 186 countries and covers the period from 1919 to 2019.

3.1.2 Quality of economic institutions

In our model, the quality of the economic institutions determines how likely it is that people lose parts of their income to the elite. We consider this likelihood as a latent variable. To obtain an index that reflects the quality of the economic institutions, we aggregate different measures that are likely to be correlated with economic institutional quality as defined in our model. All indices are taken from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) database (Coppedge et al., 2021). The first indicator reflects the extent to which private property is protected by the law. We choose this indicator, because if a legal framework is weakly developed in this regard, elites hardly need to fear consequences if they steal a part of people’s income. However, for two reasons, we believe that the V-Dem index of private property is not a perfect measure for our purpose. First, this indicator also takes into account how well the law protects the property of the elite. Second, laws that establish private property rights do not suffice to fully protect the people. For instance, when a victim cannot bring his/her case before the courts or if judges and other public officials favor the elite, formal private property rights are of relatively little value. Hence, when creating our index of economic institutional quality, we also use V-Dem’s indicators on access to courts, transparent law enforcement, court independence, and the impartiality of the public administration (for more details on these measures, see Appendix A). For computing an indicator of economic institutional quality, we standardize the five V-Dem measures to the 0-1 interval and calculate an unweighted average.Footnote 11

3.1.3 Human capital

As common in comprehensive country-level studies, we exploit educational attainment data to measure the stock of human capital. More specifically, our measure of human capital is the average number of years that the citizens of country (aged 15 and above) attended school. To obtain data on educational attainment, we use several sources. Our first source is the database by Barro and Lee (2013). The most recent version of this database includes data for 146 countries and the period from 1950 to 2015. For a sub-sample of countries, these authors also publish data for earlier periods (Barro and Lee, 2015; Lee and Lee, 2016).Footnote 12 If a country is not covered by the Barro-Lee database, we exploit information from V-Dem or the updated version of the database by Cohen and Soto (2007). When combining the human capital data with our measures for economic institutional quality and democracy, we end up with an (unbalanced) panel data set of 150 countries (for a list, see Appendix Table B.1).

3.2 Empirical framework

Our theoretical model predicts that transitions from autocracy to democracy lead to improvements in the quality of the economic institutions. The standard approach for testing this prediction is to estimate the dynamic regression model:

where c is the country and t a five-year period. The dependent variable is the level of economic institutional quality (E). The explanatory variable of interest is the level of democracy (D). Furthermore, our model includes country fixed effects (\(\xi\)) and period fixed effects (\(\theta\)). According to our model, we should find that the parameter estimate \({\hat{\beta }}_1\) is positive and statistically significant.

The second key prediction of our model concerns the role of human capital for the relationship between democracy and institutional quality. More specifically, our model suggests that the improvement in the quality of the economic institutions that results from a democratization is larger if people command a high level of human capital. To check whether this predictions holds, we augment our baseline model in the following manner:

where H denotes the level of human capital. The model prediction will be confirmed if \({\hat{\beta }}_3 > 0\).

The results from estimating models such as (15) and (16) must be interpreted with caution since they might be biased due to the following endogeneity issues. First, our measures of democracy and human capital suffer from measurement errors. Hence, we expect attenuation biases. Second, causality may run from the quality of the economic institutions to human capital and democracy. For instance, people might devote more time to schooling if institutional quality is good. Finally, autocracies may differ from democracies in unobserved characteristics. If these factors also affect the quality of the economic institutions, an omitted variable bias exists.

Addressing the aforementioned endogeneity problems is challenging. In country-level analysis, a common way is to use an instrumental variable approach. We follow this approach and exploit established instruments for democracy and human capital. These instruments are based on two basic facts. First, differences in human capital are often historically rooted and persist over time (see, e.g., Huillery, 2009; Gallego, 2010; Rocha et al., 2017). The second fact is that transitions from autocracy to democracy (or vice versa) often occur in regional waves (see, e.g., Huntington, 1993; Teorell, 2010). Prime examples of regional waves are the changes in the Mediterranean area (1970s), in South America (1980s), and in Eastern-Central Europe (1990s). Consequently, we instrument the current stock of human capital with a lagged value (see also Acemoglu et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2011; Madsen and Murtin, 2017) and the degree of democratization with the average level of democracy of the nearby countries (see also Acemoglu et al., 2019; Aidt and Jensen, 2014; Dorsch and Maarek, 2019; Persson and Tabellini, 2009). Hence, our first-stage equations have the following form:

where \(\tau\) indicates the number of lags.Footnote 13 The jack-knifed regional level of democracy is computed as:

where \(r_i\) denotes the region in which country i is located.

Our instrumental variable approach produces reliable estimates for the relationship between institutional quality, democracy, and human capital if two assumptions hold. First, the instruments must be sufficiently correlated with the explanatory variables of interest. To illustrate that our instrumental variables satisfy this key assumption, our regression tables will present the results of different weak instrument tests. The other assumption behind our instrumental variable approach is that—conditional on control variables—the instruments affects the quality of the economic institutions only via our explanatory variables of interest. We admit that this assumption might be violated for different reasons. To reduce the risk that the exclusion restriction is violated, we will block alternative channels by adding the lagged dependent variable as well as several time-varying controls to our regression model.

3.3 Baseline results

Column 1 of Table 1 presents results from estimating (15) when measuring democracy with the continuous ML indicator and using an index of economic institutional quality that takes into account information about private property protection, access to courts, judiciary independence, the transparency of the law enforcement, and public officials’ impartiality (for details, see Sect. 3.1). Our unbalanced baseline sample covers 150 countries and the period from 1920 to 2019. As common in the related literature, we average the data over five-year periods. Consistent with the first key prediction of our theoretical framework, we observe that the parameter estimate \({\hat{\beta }}_1\) is larger than zero and statistically significant at the 1%-level. Put differently, our results suggest that economic institutional quality improves after a transition towards democracy.

In Column 2, we show results from our augmented fixed effect model to investigate whether the relationship between the degree of democratization and the quality of the economic institutions depends on the level of human capital. As extensively outlined in Sect. 2.2, our model implies that the improvements in economic institutional quality that follow a democratization are more pronounced if people command a high level of human capital. If this model prediction is correct, we should not only find positive and statistically significant estimates for \(\beta _1\) but also for \(\beta _3\). Apparently, this is the case.

The results reported in the first two columns of Table 1 need to be interpreted with great caution because the fixed effect approach does not fully account for endogeneity problems such as unobserved confounders, reverse causality, and measurement error in our explanatory variables. To partly alleviate the concern that our findings are biased because of these problems, we show the results of instrumental variable regressions in Columns 3 and 4. We observe that the estimates of our parameters of interest remain positive and statistically significant. Compared with our fixed effect results, we find a (slight) increase in the size of the parameter estimates. We believe that this change is plausible, especially because the educational attainment data suffers from measurement errors and is thus likely to cause an attenuation bias.

In the bottom part of Table 1, we present standard first-stage diagnostics. The first- stage regressions are reported in Appendix Table B.2. All statistics indicate that the instrumental variables are sufficiently strong. More specifically, we report first-stage F- statistics proposed by Sanderson and Windmeijer (2016) and find that they exceed the relevant Stock and Yogo (2005) critical values.Footnote 14 We also present the p-values of the Anderson and Rubin (1949) test and the Stock and Wright (2000) test. Neither of the tests suggests a weak instrument problem. From our perspective, the strength of the instruments is hardly surprising given that several studies document the persistence of human capital through time (see, e.g., Huillery, 2009; Rocha et al., 2017) as well as the existence of regional spillovers throughout political transitions (see, e.g., Gassebner et al., 2013; Teorell, 2010).

3.4 Robustness checks

Our baseline measure for the quality of the economic institutions consists of five sub-indicators. A concern may be that our results are driven by one particular aspect of institutional quality. To allay this concern, we show separate estimates for each of the sub-indicators in Appendix Table B.3. We see that our two parameters of interests are positive and statistically significant at conventional levels in all five analyses. The sub-indicators for private property rights and access to courts can even further decomposed because V-Dem provides gender-specific indicators. However, the estimates reported in Appendix Table B.4 do not provide evidence for gender-related heterogeneities.

The appendix also presents the results of various sub-sample analyses. In particular, Appendix Table B.5 illustrates how our estimates change if we separately exclude all countries from a particular continent. In Appendix Table B.6, we limit our analysis to specific periods (1970 – 2019, 1945 – 2019, 1920 – 1989). We find that the regression coefficients of the parameters \(\beta _1\) and \(\beta _3\) are positive and statistically significant in all estimations. This robustness is reassuring since it allays the concern that our baseline results are driven by a particular group of countries or time period.

As outlined in Sect. 3.1, the literature includes several democracy indices. Out of these measures, we use the continuous Machine Learning index developed by Gründler and Krieger (2016, 2022) as our baseline indicator since we think that it has a more sophisticated aggregation method and thus creates more reliable estimates than other indicators (for details, see Gründler and Krieger, 2021). To check whether our results hold if we change the measure of democracy, we use four alternative indicators: (i) the Boix-Miller-Rosato index, (ii) the binary Machine Learning measure, (iii) the Polyarchy index by Teorell et al. (2019), and (iv) the Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy. The results of our robustness checks are reported in Appendix Table B.7. When comparing these results with the results presented in Table 1, we find only minor differences.

In our main analysis, we apply data averaged over five years. We choose this period length since Barro and Lee’s educational attainment data is only available every fifth year. To test whether that this choice influences our findings, we replicate our baseline table with ten-year averages. Appendix Table B.9 illustrates that our results are barely affected by our choice.

Finally, we augment our regression models by adding a set of time-varying control variables. The basic rationale behind this step is to block off alternative mechanisms through which our instruments may affect the quality of the economic institutions. Our list of control variables includes: the level of economic development (measured by the per-capita GDP), the population size, an indicator of civil conflict, the regional level of economic institutional quality, and a Gini-coefficient that reflects the inequality in educational attainment. An immediate consequence of our model extension is that the number of observations decreases by more than 10% (see Appendix Fig. B.8). With regard to the parameters of interest, we observe hardly any change compared to Table 1.

3.5 Discussion of an alternative explanation

We have found only one empirical analysis that investigates whether the relationship between democracy and economic institutional quality depends on the level of human capital. Fortunato and Panizza (2015) exploit data from the International Country Risk Guide to show that the interaction between the levels of democracy and human capital positively correlates with institutional quality. These authors explain their result with differences among democratic regimes. More specifically, Fortunato and Panizza (2015) argue that highly educated voters elect more competent political leaders and that the competent leaders implement better economic institutions. By contrast, our theoretical model suggests that differences among the autocratic regimes explain why institutional quality improves more after a democratic transition if people command a high level of human capital.

In their article, Fortunato and Panizza (2015) do not offer empirical evidence that supports their explanation. The remainder of this section thus examines whether their hypothesis has great explanatory power. To this end, we need a measure for leaders’ competence, which is difficult because of conceptual and data availability reasons. The standard approach in the literature is to exploit information on leaders’ education to approximate the competence of politicians (see, e.g., Baltrunaite et al., 2014; Besley et al., 2011; Galasso and Nannicini, 2011; Kotakorpi and Poutvaara, 2011). A rationale behind this imperfect proxy is that educated people make on average better economic decisions (see, e.g., Agarwal and Mazumder, 2013; D’Acunto et al., 2019). To obtain data on the education of political leaders, we use and extend the database by Besley et al. (2011) and Besley and Reynal-Querol (2011). More specifically, we exploit their database and a number of web sources to identify which political leaders hold a college degree. In our analysis, we use this information in two ways. First, we add our measures of leader’s competence as control variable to our regression models. Appendix Table B.10 illustrates that our two parameters of interest (\(\beta _1\), \(\beta _3\)) remain positive and statistically significant in this case. In the fixed effect analyses, we also find supporting evidence for the hypotheses that competent political leaders implement better economic institutions. Second, we use our measure of leaders’ competence as dependent variable. Appendix Table B.11 presents the results of the corresponding regressions. In line with Besley and Reynal-Querol (2011), we observe that the competence of political leaders increases after a democratic transition. However, our findings do not substantiate the argument by Fortunato and Panizza (2015) since we do not see that this relationship becomes stronger if people command a high level of human capital.

4 Conclusions

We present a simple theoretical model that predicts an increase in the quality of the economic institutions in the aftermath of a transition from autocracy to democracy. In addition, our model predicts that this improvement is larger when the level of human capital is high. Results form a comprehensive country-level panel data analysis confirm these predictions.

From a broader perspective, we believe that our paper has two key messages. First, there is heterogeneity in the economic consequences of political transitions. Getting a better understanding of these heterogeneities is important, for instance to avoid that people develop illusive beliefs about how their economic well-being will improve after a democratization. Unfulfilled expectations may result in dissatisfaction and thus might increase the support for leaders with authoritarian attitudes. Second, our paper shows that researchers should pay more attention to the differences among autocracies when examining the consequence of democratic transitions. In this regard, we second Dorsch and Maarek (2019) who find that the initial level of income inequality determines how redistribution changes after a democratization.

Notes

For studies that confirm this view, see Acemoglu et al. (2001, 2002, 2005a, 2005b), Acemoglu and Robinson (2013), De Long and Shleifer (1993), Hall and Jones (1999), Knack and Keefer (1995), North (1991), North and Weingast (1989), Pinkovskiy (2017), Rodrik et al. (2004), Rodrik (2008), and Sokoloff and Engerman (2000).

The literature provides different definitions of economic institutions. In this paper, we use a narrow definition, focusing on core aspects such as private property protection, judiciary independence, and access to justice. Aspects such as the tax burdens, the independence of the central bank, or the fiscal rules are not taken into account.

For empirical studies that examine this relationship, see Adsera et al. (2003), Assiotis and Sylwester (2015), De Haan and Sturm (2003), Leblang (1996), Lundström (2005), Knutsen (2011), Méon and Sekkat (2022), Pitlik (2008), and Rode and Gwartney (2012). The dominant view is that democratic regimes have better economic institutions than autocratic regimes. Another but somehow related strand of research investigates the effect of democracy on economic liberalization (Giuliano et al., 2013; Grosjean and Senik, 2011; Giavazzi and Tabellini, 2005).

Some studies distinguish between two types of elites that split along economic interests (see, e.g., Galor et al., 2009; Krieger, 2022; Llavador and Oxoby, 2005). We do not follow these studies since such a differentiation would increase the complexity of our model, but would hardly change the model’s key predictions.

Assuming within-group homogeneity significantly simplifies the model. Replacing this assumption with the assumption that group members are heterogeneous because of differences in human capital has no consequences for the main predictions of the model.

The way of how we model the decision of the government resembles the approach by Acemoglu and Robinson (2005).

We do not specify a particular channel through which weak economic institutions lead to the income losses since we think that there are several of them. For instance, it might be that private property is weakly protected by the law. Other mechanisms might be that the people lack an opportunity to sue before courts or that judges and other public officials are favoring the elite when making decisions. In our empirical analysis, we consider the quality of the economic institutions as latent variable. To get a measure of economic institutional quality, we aggregate several measures that reflect (for instance) the extent of private property protection or the independence of the judiciary (for details, see Sect. 3.1).

Following Besley and Ghatak (2010), we assume an additive utility function. The key advantage of this functional form is that a closed form solution can easily be calculated. For the main predictions of our model, this functional form assumption is not necessary because for them we only require that people’s utility and commercial activities are increasing in the level of human capital and the quality of the economic institutions. This would also be the case if we assume a multiplicative approach, for instance modeled with another Cobb-Douglas function.

Studying whether our explanation or the explanation given by Acemoglu and Robinson (2006, 2008) applies may be an interesting question for future research. In this project, we do not address this issue, but focus primarily on the role of human capital for the effect of democracy on institutional quality.

We believe that this concept fits well together with our model because all three aspects are necessary such that the people can influence government decisions.

Out of the 186 countries for which the Machine Learning indicator is available, 11 countries are not covered by the V-Dem database. These countries therefore disappear from our sample.

All this data can be downloaded from the webpage http://www.barrolee.com/.

We tried different lags and observed that the estimation results are fairly robust to changes in the lag structure. Below, we use the stock of human capital 40 years ago (8th lag) as an instrument for the current stock of human capital. Results for other lags are available upon request.

The Stock and Yogo (2005) critical values are 22.3 for 10% maximal IV size and 13.9 for 5% maximal IV relative bias.

References

Acemoglu, D., Gallego, F. A., & Robinson, J. A. (2014). Institutions, human capital, and development. Annual Review of Economics, 6(1), 875–912.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2002). Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1231–1294.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. Handbook of Economic Growth (pp. 385–472). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 95(3), 546–579.

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). A theory of political transitions. American Economic Review, 91(4), 938–963.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2006). De facto political power and institutional persistence. American Economic Review, 96(2), 325–330.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). Persistence of power, elites, and institutions. American Economic Review, 98(1), 267–93.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Crown Business.

Adsera, A., Boix, C., & Payne, M. (2003). Are you being served? Political accountability and quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 19(2), 445–490.

Agarwal, S., & Mazumder, B. (2013). Cognitive abilities and household financial decision making. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5(1), 193–207.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2014). Workers of the world, unite! Franchise extensions and the threat of revolution in Europe, 1820–1938. European Economic Review, 72, 52–75.

Anderson, T. W., & Rubin, H. (1949). Estimation of the parameters of a single equation in a complete system of stochastic equations. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 20(1), 46–63.

Assiotis, A., & Sylwester, K. (2015). Does democracy promote the rule of law? Journal of Economic Development, 40(1), 63.

Baltrunaite, A., Bello, P., Casarico, A., & Profeta, P. (2014). Gender quotas and the quality of politicians. Journal of Public Economics, 118, 62–74.

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J. W. (2013). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 184–198.

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J.-W. (2015). Education matters. Global schooling gains from the 19th to the 21st Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baum, M. A., & Lake, D. A. (2003). The political economy of growth: Democracy and human capital. American Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 333–347.

Becker, S. O., Hornung, E., & Woessmann, L. (2011). Education and catch-up in the industrial revolution. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 3(3), 92–126.

Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2010). Property rights and economic development. Handbook of Development Economics (pp. 4525–4595). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Besley, T., Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2011). Do educated leaders matter? Economic Journal, 121(554), 205–227.

Besley, T., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2011). Do democracies select more educated leaders? American Political Science Review, 105(3), 552–566.

Bjørnskov, C., & Rode, M. (2020). Regime types and regime change: A new dataset on democracy, coups, and political institutions. Review of International Organizations, 15(2), 531–551.

Boix, C., Miller, M., & Rosato, S. (2013). A complete data set of political regimes, 1800–2007. Comparative Political Studies, 46(12), 1523–1554.

Cohen, D., & Soto, M. (2007). Growth and human capital: Good data, good results. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 51–76.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Skaaning, S.-E., & Teorell, J. (2021). V-Dem codebook v11.1.

De Haan, J., & Sturm, J.-E. (2003). Does more democracy lead to greater economic freedom? New evidence for developing countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(3), 547–563.

De Long, J. B., & Shleifer, A. (1993). Princes and merchants: European city growth before the industrial revolution. Journal of Law and Economics, 36(2), 671–702.

Dorsch, M. T., & Maarek, P. (2019). Democratization and the conditional dynamics of income distribution. American Political Science Review, 113(2), 385–404.

D’Acunto, F., Hoang, D., Paloviita, M. & Weber, M. (2019). IQ, expectations, and choice. Working Paper 25496, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Fortunato, P., & Panizza, U. (2015). Democracy, education and the quality of government. Journal of Economic Growth, 20(4), 333–363.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fujiwara, T. (2015). Voting technology, political responsiveness, and infant health: Evidence from Brazil. Econometrica, 83(2), 423–464.

Galasso, V., & Nannicini, T. (2011). Competing on good politicians. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 79–99.

Gallego, F. A. (2010). Historical origins of schooling: The role of democracy and political decentralization. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(2), 228–243.

Galor, O., Moav, O., & Vollrath, D. (2009). Inequality in landownership, the emergence of human-capital promoting institutions, and the great divergence. Review of Economic Studies, 76(1), 143–179.

Gassebner, M., Lamla, M. J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2013). Extreme bounds of democracy. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57(2), 171–197.

Giavazzi, F., & Tabellini, G. (2005). Economic and political liberalizations. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(7), 1297–1330.

Giuliano, P., Mishra, P., & Spilimbergo, A. (2013). Democracy and reforms: Evidence from a new dataset. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5(4), 179–204.

Grosjean, P., & Senik, C. (2011). Democracy, market liberalization, and political preferences. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 365–381.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2016). Democracy and growth: Evidence from a machine learning indicator. European Journal of Political Economy, 45(1), 85–107.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2021). Using machine learning for measuring democracy: A practitioners guide and a new updated dataset for 186 countries from 1919 to 2019. European Journal of Political Economy, 70(1), 102047.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2022). Should we care (more) about data aggregation? European Economic Review, 142(1), 104010.

Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

Hayek, F. (1944). The road to serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Huillery, E. (2009). History matters: The long-term impact of colonial public investments in French West Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(2), 176–215.

Huntington, S. P. (1993). The third wave: Democratization in the late twentieth century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1995). Institutions and economic performance: Cross-country tests using alternative institutional measures. Economics & Politics, 7(3), 207–227.

Knutsen, C. H. (2011). Democracy, dictatorship and protection of property rights. Journal of Development Studies, 47(1), 164–182.

Knutsen, C. H., & Wig, T. (2015). Government turnover and the effects of regime type: How requiring alternation in power biases against the estimated economic benefits of democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 48(7), 882–914.

Kotakorpi, K., & Poutvaara, P. (2011). Pay for politicians and candidate selection: An empirical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 877–885.

Kotschy, R., & Sunde, U. (2017). Democracy, inequality, and institutional quality. European Economic Review, 91, 209–228.

Krieger, T. (2022). Elites and health infrastructure improvements in industrializing regimes. CESifo Working Paper.

Krieger, T., & Meierrieks, D. (2016). Political capitalism: The interaction between income inequality, economic freedom and democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 45, 115–132.

Leblang, D. A. (1996). Property rights, democracy and economic growth. Political Research Quarterly, 49(1), 5–26.

Lee, J.-W., & Lee, H. (2016). Human capital in the long run. Journal of Development Economics, 122, 147–169.

Llavador, H., & Oxoby, R. J. (2005). Partisan competition, growth, and the franchise. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 1155–1189.

Lundström, S. (2005). The effect of democracy on different categories of economic freedom. European Journal of Political Economy, 21(4), 967–980.

Madsen, J. B., & Murtin, F. (2017). British economic growth since 1270: The role of education. Journal of Economic Growth, 22(3), 229–272.

Méon, P.-G., & Sekkat, K. (2022). A time to throw stones, a time to reap: How long does it take for democratic transitions to improve institutional outcomes? Journal of Institutional Economics, 18(3), 429–443.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. The Journal of Economic History, 49(4), 803–832.

Olson, M. (1993). Dictatorship, democracy, and development. American Political Science Review, 87(3), 567–576.

Pemstein, D., Meserve, S. A., & Melton, J. (2010). Democratic compromise: A latent variable analysis of ten measures of regime type. Political Analysis, 18(4), 426–449.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2009). Democratic capital: The nexus of political and economic change. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(2), 88–126.

Pinkovskiy, M. L. (2017). Growth discontinuities at borders. Journal of Economic Growth, 22(2), 145–192.

Pitlik, H. (2008). The impact of growth performance and political regime type on economic policy liberalization. Kyklos, 61(2), 258–278.

Przeworski, A., & Limongi, F. (1993). Political regimes and economic growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(3), 51–69.

Rocha, R., Ferraz, C., & Soares, R. R. (2017). Human capital persistence and development. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(4), 105–36.

Rode, M., & Gwartney, J. D. (2012). Does democratization facilitate economic liberalization? European Journal of Political Economy, 28(4), 607–619.

Rodrik, D. (2008). One economics, many recipes: Globalization, institutions, and economic growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2), 131–165.

Sanderson, E., & Windmeijer, F. (2016). A weak instrument F-test in linear IV models with multiple endogenous variables. Journal of Econometrics, 190(2), 212–221.

Skaaning, S.-E., Gerring, J., & Bartusevičius, H. (2015). A lexical index of electoral democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 48(12), 1491–1525.

Sokoloff, K. L., & Engerman, S. L. (2000). Institutions, factor endowments, and paths of development in the New World. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 217–232.

Stasavage, D. (2005). Democracy and education spending in Africa. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 343–358.

Stock, J., & Yogo, M. (2005). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. Identification and Inference for Econometric Models: Essays in honor of Thomas J. Rothenberg (pp. 80–108). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stock, J. H., & Wright, J. H. (2000). GMM with weak identification. Econometrica, 68(5), 1055–1096.

Sunde, U., Cervellati, M., & Fortunato, P. (2008). Are all democracies equally good? The role of interactions between political environment and inequality for rule of law. Economics Letters, 99(3), 552–556.

Teorell, J. (2010). Determinants of democratization: Explaining regime change in the world, 1972–2006. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Teorell, J., Coppedge, M., Lindberg, S., & Skaaning, S.-E. (2019). Measuring polyarchy across the globe, 1900–2017. Studies in Comparative International Development, 54(1), 71–95.

Acknowledgements

I greatly benefited from comments by two referees, the associate editor, and Toke Aidt, Enzo Brox, Klaus Gründler, Pierre-Guillaume Meon, Jan-Eckbert Sturm and, Heinrich Urspung. I also received very helpful feedback when presenting this paper at the annual conference of the European Public Choice Society, the Political Economy of Democracy and Dictatorship workshop, the CESifo political economy workshop, and the Silvaplana political economy workshop.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krieger, T. Democracy and the quality of economic institutions: theory and evidence. Public Choice 192, 357–376 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00990-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00990-6