Abstract

Over the last four decades, banking crises around the globe have become longer. Along with the unprecedented government responses to the Great Recession of 2007–2008, protracted financial crises have led scholars to ask whether political decisions were somehow to blame. Despite growing concerns, little attention has been paid to the political and institutional determinants of financial crisis duration. This paper considers the role of these factors in determining the duration of systemic banking, currency, sovereign debt, and twin or triple coinciding crises. Relying on an extensive database of 125 countries observed over the 1976–2017 period and estimating a discrete-time duration model, we find that the electoral cycle, political ideology, majority governments, institutional quality, and central bank independence matter. This study shows that the duration dynamics of financial crises are idiosyncratic and must be examined individually. Finally, allowing for more flexible duration dependence patterns, we observe that the durations of both banking and twin or triple coinciding crises follow a nonmonotonic cubic model, while the probability of debt crisis ending declines monotonically over time.

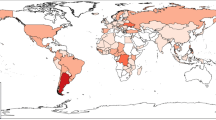

Source: Author's calculations

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Claessens et al. (2012) examine the duration dependence of economic recessions, which might not necessarily imply financial crises.

The absence of empirical research on the duration of the different types of financial crises might be due to (1) difficulties in identifying different types of financial crises, and (2) the limited number of observations of crisis episodes.

“Twin deficits” refer to the rapid expansion of current account deficits and deterioration of fiscal balances (Broz, 2013).

BoC-BoE Database of Sovereign Defaults is available at: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2020/06/staff-analytical-note-2020-13/.

These two groups of countries are identified based on the country classifications of the World Economic Outlook. For details, see https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/02/weodata/groups.htm.

One exception is Mecagni et al. (2007) who examine the determinants of the duration of capital account crisis.

The duration of all crises “in general” may not accurately capture the states of financial crises because the exit state of a type of financial crisis is overlapped by the duration of another type. In this paper, due to the prolonged duration of sovereign debt crises, the probability of exiting crisis states of all crises is highly influenced by the duration of debt crises.

According to Allison (2014), 100(exp(b)−1) corresponds to the percentage change in the hazard with a one-unit increase in the explanatory variable, ceteris paribus.

Alternatively, this can be computed as 100(exp(b)−1), which means that the probability of a currency crisis ending is 40% higher when left-wing governments are in office.

As shown in Table 1, the average duration of banking crises over the period 1970–2017 is 3.74 years in developed countries, while the figure for developing countries is only 2.91 years.

Due to space limitations, the results are not reported here but are available upon request.

The results for all our sensitivity analysis and robustness checks are not reported here but are available upon request.

As CBI data are only available to 2012, regressions are limited to the period 1976–2012.

As the data for INSQL-PCA only cover the period 1985–2017, our models lose several observations.

Due to space limitations, the regression results are not reported here but are available upon request.

References

Agnello, L., Castro, V., & Sousa, R. M. (2019). On the duration of sovereign ratings cycle phases. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.01.016

Aidt, T., Castro, V., & Martins, R. (2018). Shades of red and blue: Political ideology and sustainable development. Public Choice, 175, 303–323.

Aisen, A., & Veiga, F. J. (2013). How does political instability affect economic growth? European Journal of Political Economy, 29, 151–167.

Alesina, A., & Drazen, A. (1991). Why are stabilizations delayed? American Economic Review, 81, 1170–1188.

Alesina, A., & Perotti, R. (1996). Income distribution, political instability, and investment. European Economic Review, 40, 1203–1228.

Allison, P. D. (1982). Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociological Methodology, 13, 61–98.

Allison, P. D. (2014). Quantitative applications in the social sciences: Event history and survival analysis. SAGE Publications.

Amaglobeli, D., End, N., Jarmuzek, M., & Palomba, G. (2017). The fiscal costs of systemic banking crises. International Finance, 20(1), 2–25.

Balteanu, I., & Erce, A. (2018). Linking bank crises and sovereign defaults: Evidence from emerging markets. IMF Economic Review, 66(4), 617–664.

Bartels, L. M. (2013). Effects of the Great Recession. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 65, 47–75.

Basu, S., & Bundick, B. (2017). Uncertainty shocks in a model of effective demand. Econometrica, 85(3), 937–958.

Bekaert, G., Hoerova, M., & Lo Duca, M. (2013). Risk, uncertainty and monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(7), 771–788.

Bergoeing, R., Kehoe, P. J., Kehoe, T. J., & Soto, R. (2002). A decade lost and found: Mexico and Chile in the 1980s. Review of Economic Dynamics, 5, 166–205.

Bermpei, T., Kalyvas, A., & Nguyen, T. C. (2018). Does institutional quality condition the effect of bank regulations and supervision on bank stability? Evidence from emerging and developing economies. International Review of Financial Analysis, 59, 255–275.

Bernhard, W., Broz, J. L., & Clark, W. R. (2002). The political economy of monetary institutions. International Organization, 56(4), 693–723.

Bjørnskov, C., & Rode, M. (2018). Crisis, ideology, and interventionist policy ratchets. Political Studies, 67, 815–833.

Brown, C. O., & Dinc, I. S. (2005). The politics of bank failures: Evidence from emerging markets. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(4), 1413–1444.

Broz, J. L. (2013). Partisan financial cycles’. In M. Kahler & D. A. Lake (Eds.), Politics in the new hard times: The Great Recession in comparative perspective’. Cornell University Press.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconomics methods and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Castro, V. (2010). The duration of economic expansions and recessions: More than duration dependence. Journal of Macroeconomics, 32, 347–365.

Castro, V., & Martins, R. (2019). Political and institutional determinants of credit booms. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 85(1), 1144–1178.

Castro, V., & Martins, R. (2020). Government ideology and economic freedom? Journal of Comparative Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2020.07.007

Cerra, V., & Saxena, S. C. (2017). Booms, crises, and recoveries: A new paradigm of the business cycle and its policy implications, International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/17/250.

Cerra, V., & Saxena, S. C. (2008). Growth dynamics: The myth of economic recovery. American Economic Review, 98(1), 439–457.

Claessens, S., Klingebiel, D., & Laeven, L. (2001). Financial restructuring in banking and corporate sector crises: What policies to pursue? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series 8386.

Claessens, S., Kose, M. A., & Terrones, M. E. (2012). How do business and financial cycles interact? Journal of International Economics, 87, 178–190.

Cole, S., Healy, A., & Werker, E. (2012). Do voters demand responsive governments? Evidence from Indian disaster relief. Journal of Development Economics, 97(2), 167–181.

De Giorgi, E., Moury, C., & Ruivo, J. P. (2014). Incumbents, opposition and international lenders: Governing Portugal in times of crisis. Journal of Legislative Studies, 21(1), 54–74.

De Haan, J., Bodea, C., Hicks, R., & Eijffinger, S. C. W. (2018). Central bank independence before and after the crisis. Comparative Economic Studies, 60, 183–202.

Del Negro, M., Giannone, D., Giannoni, M. P., & Tambalotti, A. (2019). Global trends in interest rates. Journal of International Economics, 118, 248–262.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Detragiache, E. (1998). The determinants of banking crises in developing and developed countries. IMF Staff Papers, 45(1), 81–109.

Detragiache, E., & Ho, G. (2010). Responding to banking crises: Lessons from cross-country evidence, International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/10/18.

Edwards, S., & Tabellini, G. (1991a). Political instability, political weakness and inflation: An empirical analysis, NBER Working Paper No. 3721.

Edwards, S., & Tabellini, G. (1991). Explaining fiscal policies and inflation in developing countries. Journal of International Money and Finance, 10, 16–48.

Frankel, J. A., & Rose, A. K. (1996). Currency crashes in emerging markets: An empirical treatment. Journal of International Economics, 41, 351–366.

Funke, M., Schularick, M., & Trebesch, C. (2016). Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870–2014. European Economic Review, 88, 227–260.

Galasso, V. (2014). The role of political partisanship during economic crises. Public Choice, 158, 143–165.

Garriga, A. C. (2016). Central bank independence in the world: A new data set. International Interactions, 42, 849–868.

Gerring, J., Thacker, S. C., & Alfaro, R. (2012). Democracy and human development. The Journal of Politics, 74(1), 1–17.

Hess, W., & Persson, M. (2012). The duration of trade revisited. Empirical Economics, 43, 1083–1107.

Hibbs, D. A., Jr. (1977). Political parties and macroeconomic policy. The American Political Science Review, 71(4), 1467–1487.

Honohan, P., & Klingebiel, D. (2003). The fiscal cost implications of an accommodating approach to banking crises. Journal of Banking & Finance, 27(8), 1539–1560.

Ilzetzki, E., Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2019). Exchange arrangements entering the Twenty-first century: Which anchor will hold? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(2), 599–646.

Jannsens, N., Potjagailo, G., & Wolters, M. H. (2019). Monetary policy during financial crises: Is the transmission mechanism impaired? International Journal of Central Banking, 15(4), 81–126.

Jenkins, S. P. (1995). Easy estimation methods for discrete-time duration models. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 57, 129–138.

Jens, C. E. (2017). Political uncertainty and investment: Casual evidence from U.S. gubernatorial elections. Journal of Financial Economics, 124(3), 563–579.

Keefer, P. (2007). Elections, special interests, and financial crisis. International Organization, 61, 607–641.

Kollmann, R., Ratto, M., Roeger, W., & In’t Veld, J. (2013). Fiscal policy, banks and the financial crisis. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, 37, 387–403.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2013). Systemic banking crises database. IMF Economic Review, 61, 225–270.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2020). Systemic banking crises database II. IMF Economic Review, 68, 307–361.

Lane, P. R., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2011). The cross-country incidence of the Global Crisis. IMF Economic Review, 59(1), 77–110.

Leblang, D. (2003). To devalue or to defend? The political economy of exchange rate policy. International Studies Quarterly, 47(4), 533–559.

Lindvall, J. (2014). The electoral consequences of two great crises. European Journal of Political Research, 53, 747–765.

Lischinsky, B. (2003). The puzzle of Argentina’s debt problem: Virtual dollar creation? In J. J. Teunissen & A. Akkerman (Eds.), The crisis that was not prevented: Lessons for Argentina, the IMF, and globalisation. The Hague.

McManus, I. P. (2019). The re-emergence of partisan effects on social spending after the global financial crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57, 1274–1291.

Mecagni, M., Atoyan, R., Hofman, D., & Tzanninis, D. (2007). The duration of capital account crises: An empirical analysis, IMF Working Paper No. WP/07/258.

Mian, A., Sufi, A., & Trebbi, F. (2014). Resolving debt overhang: Political constraints in the aftermath of financial crises. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 6(2), 1–28.

Nguyen, T. C., Castro, V., & Wood, J. A. (2020). Political environment and financial crises. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(1), 417–438.

Nguyen, T. C., Castro, V., & Wood, J. A. (2022). A new comprehensive database of financial crises: Identification, frequency, and duration. Economic Modelling. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2022.105770

O’Keeffe, M., & Terzi, A. (2015). The political economy of financial crisis policy, Bruegel Working Paper 2015/06.

Persson, T., & Svensson, L. E. O. (1989). Why a stubborn conservative would run a deficit: Policy with time-inconsistent preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(2), 325–345.

Perugini, C., Holscher, J., & Collie, S. (2016). Inequality, credit and financial crises. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 40, 227–257.

Prentice, R. L., & Gloeckler, L. A. (1978). Regression analysis of grouped survival data with application to breast cancer data. Biometrics, 34, 57–67.

Redl, C. (2020). Uncertainty matters: Evidence from close elections. Journal of International Economics, 124, 1–16.

Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2014). This time is different: A panoramic view of eight centuries of financial crises. Annals of Economics and Finance Society for AEF, 15, 1065–1188.

Rosas, G. (2006). Bagehot or bailout? An analysis of government responses to banking crises. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 175–191.

Ryu, K. (1995). Analysis of a continuous-time proportional hazard model using discrete duration data. Econometric Reviews, 14, 299–313.

Sacchi, S., & Roh, J. (2016). Conditionality, austerity and welfare: Financial crisis and its impact on welfare in Italy and Korea. Journal of European Social Policy, 26, 358–373.

Sattler, T., & Walter, S. (2009). Globalization and government short-term room to maneuver in economic policy: An empirical analysis of reactions to currency crises. World Political Science Review, 5(1), 1–30.

Savage, L. (2019). The politics of social spending after the great recession: The return of partisan policy making. Governance, 32, 123–141.

Shahidi, F. V. (2015). Welfare capitalism in crisis: A qualitative comparative analysis of labour market policy responses to the Great Recession. Journal of Social Policy, 44, 659–686.

Starke, P. (2006). The politics of welfare state retrenchment: A literature review. Social Policy & Administration, 40, 104–120.

Stone, C. (2020). Fiscal stimulus needed to fight recessions. Lessons from the Great Recession. Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities Report. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/fiscal-stimulus-needed-to-fight-recessions

Talving, L. (2017). The electoral consequences of austerity: Economic policy voting in Europe in times of crisis. West European Politics, 40, 560–583.

Thompson, W. A. (1977). On the treatment grouped observations in life studies. Biometrics, 33, 463–470.

UNDP (2020). Covid-19 and human development: Assessing the crisis, envisioning the recovery. 20202 Human Development Perspectives. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/hdp-covid

Walter, S. (2008). The limits and rewards of political opportunism: How electoral timing affects the outcome of currency crises. European Journal of Political Research, 48, 367–396.

Weatherford, M. S. (1978). Economic conditions and electoral outcomes: Class differences in the political response to recession. American Journal of Political Science, 22, 917–938.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed.). The MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ahmad Hassan Ahmad, Sushanta Mallick, Rodrigo Martins, Alistair Milne, Ricardo Sousa, the anonymous referees, and the Editor for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by TCN. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TCN and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, T.C., Castro, V. & Wood, J. Political economy of financial crisis duration. Public Choice 192, 309–330 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00986-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00986-2