Abstract

Legislative scholars often assume that legislators are motivated by concerns over re-election. This assumption implies that legislators are forward-looking and are motivated by a concern over what their re-election constituency will look like during their next electoral cycle. In this research, we show how the forward-looking nature of legislators motivates members of the U.S. House of Representatives to represent both their home district and their neighboring districts in their choices regarding when to support their own party. Using survey responses to the 2006, 2008, and 2010 Cooperative Congressional Elections Study to construct measures of Congressional District ideology, empirical analysis is strongly supportive of our claims. Legislators’ choices are strongly influenced both by the ideology of their home district and that of the districts that neighbor their home district. Thus, the electoral connection between citizens and representatives extends beyond a legislator’s own constituents to include the constituents in neighboring districts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The first violation was the passage of relief aid to areas struck by Hurricane Sandy.

Only 35 % of the Republicans opposing the bill came from states won by President Obama.

When each party is satisfied with the legislative status quo, those parties do not propose legislation at all. This immediately implies that proposed legislation attempting to move the status quo tends to do so in a consistent ideological direction.

Our theory focuses on the relationship between the ideology of constituents and the party loyalty of legislators because there are under appreciated consequences of proximity models of representation for the party loyalty of legislators.

Hereafter, we will refer to individual legislators voting against the majority of their party as “shirking” or “being disloyal.”

This spatial account of legislative voting and cross-pressuring already has substantial support in the U.S. legislative politics literature. Research has consistently shown that U.S. legislators from moderate districts face electoral difficulty if they vote with their parties too often (Canes-Wrone and Cogan 2002; Carson et al. 2010; Snyder and Ting 2003; Griffin 2006). It is also worth noting that this hypothesis is not uniformly supported in comparative legislative research. A number of parliamentary legislatures actually exhibit ends-against-the-middle voting in spite of the fact that such behavior is irrational in a proximity-based model of legislative voting (Kam 2009).

Because legislators are forward-looking, and thus always making choices in the shadow of the future, redistricting need not actually have occurred to worry a legislator. A legislator worried about the future will anticipate problems that result from redistricting before that redistricting ever occurs.

There is an implicit assumption here that U.S. residents are more likely to move short distances than they are to move long distances. That is, we assume that moving within a city or county is more common than moving great distances like across states or to a different state entirely. While this is an assumption of our theory, it has robust empirical support. The 2012–2013 Census Migration Data indicates that 17,000,000 citizens aged 16 or older moved within counties while only 9,000,000 such residents moved out of their county into a new one. Additionally, within the inter-county migrants, 3.5 million moved less than 50 miles, while 2 million moved between 50 and 199 miles, 1.3 million residents moved 200–499 miles and 2.3 million moved more than 500 miles. Thus, even amongst those moving across county lines, the most common migration distance is less than 50 miles. Census Migration Data can be viewed at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/migration/data/cps/cps2013.html. Additionally, geography research has known that short-distance migration was more common than long-distance migration since at least Ravenstein (1885).

We are not suggesting the neighboring districts are more important than a legislator’s home constituency, or that the effects of neighboring districts on legislative behavior will be extremely large. Instead, we are suggesting that legislators have an incentive to consider the preferences of neighboring constituencies as one of many factors when deciding how to vote on bills.

Brady et al. (2007) found that legislators in states using primary elections position themselves closer to the primary electorate than the general election electorate. McCann (1995) found evidence that reinforced the traditional view that primaries lead to more extreme candidates. While these articles do not distinguish between open and closed primaries, the logic suggests that with the even more restricted and ideological electorate found in a closed primary there would be even more extreme candidates. There remains, however, some uncertainty about how strongly closed primaries influence candidates’ ideological extremism (McGhee et al. 2014).

It is worth noting that legislative scholarship is already quite comfortable with the notion that legislators respond to changes in their constituencies by changing their voting behavior. Bertelli and Carson (2011) state that “it is clear from both [of our] models that geographic boundary change and the corresponding uncertainty that arises from representing ‘new’ voters affects congressional voting decisions” (p. 205). We are simply asserting that forward-looking legislators are likely to anticipate these changes to their district, rather than waiting for them to happen.

In 2006, we used questions asking respondents about their feelings towards abortion, stem cell research, affirmative action, environmental protection and immigration. In the 2008 and 2010 CCES, the immigration question on the survey was dropped, and so we replace it in our estimates with a question asking respondents their preference for the provision of health insurance to under privileged children.

The correlation between our estimates of district ideology are 0.76 between 2006 and 2008 estimates and 0.82 between 2008 and 2010 estimates.

It is worth pointing out that this definition also means that some Congressional Districts have no neighbors. For example, Wyoming only has one Congressional District and so has no districts in the same state with which it shares a border. Districts without neighbors are dropped from our analysis.

In other words, we simply add together the estimated ideologies of a legislator’s neighboring districts.

We can be more precise about how many districts are surrounded by ideologically opposed districts. Using an ideology estimate of zero as the midpoint, we can calculate the percentage of Congressional Districts with ideology on one side of zero and an average neighboring district ideology on the other side of zero. Let us call these “Enemy Territory Districts.” According to the 2006 CCES 28.7 % of Congressional Districts were in enemy territory. According to the 2008 CCES, 27.1 % of Congressional Districts were in enemy territory. According to the 2010 CCES, 29.8 % of Congressional Districts were in enemy territory.

This approach is also sometimes to referred to as “fractional” logistic regression.

For legislators new to the House who do not have lagged party disloyalty scores, we use the party disloyalty of the legislator from the new legislator’s home district in the prior session. Our lagged rate of disloyalty helps control for the endogeneity that may exist between party disloyalty and district preferences. As an alternative, we could drop new legislators from the analysis. Neither choice influences the substantive findings of our analyses.

Because our estimates of Congressional District ideology come from a factor analysis of survey responses, they necessarily contain measurement error. This measurement error could potentially pose a problem for the inferences we draw. In the supplemental appendices, we attempt to address this measurement error using a sensitivity analysis approach similar to Blackwell et al. (2010).

While none of these sessions are themselves subject to a redistricting cycle (one of the mechanisms motivating our theory), forward-looking legislators need not actually experience redistricting to worry about redistricting. Forward-looking legislators will anticipate redistricting’s effect on their constituency and adapt their behavior accordingly.

In the supplemental appendices, we provide models with specifications that include the ideology of a legislator’s neighboring districts in other states. These models help us rule out the possibility that our results are driven entirely by progressive ambition. Progressively ambitious House members have no reason to respond to neighboring districts in other states, and yet our results suggest that they do respond to such neighbors.

Some may worry that (1) a legislator’s home district’s ideology and neighboring district’s ideology may be spatially correlated and (2) a legislator’s home district’s ideology may be correlated across observations. Spatial correlation between a legislator’s home district’s ideology and neighboring district ideology would imply that our measures of ideology are collinear. Collinearity drives up standard errors and results in excessively conservative hypothesis tests. Thus, spatial correlation between a legislator’s home district and neighboring district is not harming our hypothesis tests. It is in fact, making them more conservative. Spatial correlation across observations (rather than within two covariates on the same unit) would be problematic were it in the dependent variable, but spatial correlation in independent variables causes no problems for linear models. Neither of these concerns would result in excessive tendency to reject the null hypothesis.

Supplemental tests indicate that residual spatial autocorrelation in party unity scores is not a problem for our analyses.

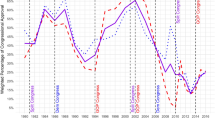

We expected that the legislators’ responsiveness to their neighboring districts would grow as redistricting approached, and thus, would reach its maximum in the 112th House. This pattern does not manifest in our results, and thus we are lead to believe that most of the motivation for legislators’ responsiveness to their neighbors comes from some combination of concerns about redistricting and migration.

We have also subset these analyses to distinguish between southern and non-southern states, and to distinguish between states which use a redistricting commission to draw district lines, and those that do not. Our results are largely stable across these distinctions. The effects we observe are slightly weaker in southern states, but are still in the expected direction and statistically significant. Our results are nearly identical when comparing commission to non-commission states. These results can be provided upon request.

We suggest that the primary reasons for legislators to respond to neighboring districts’ ideology are redistricting and migration. This necessarily begs the question of just how much short-distance migration is actually occurring within or across Congressional Districts. While we have been assured by statisticians at the U.S. Census Bureau that district-to-district migration flows are impossible to capture using Census data, Supplemental Appendix B attempts to provide some evidence regarding short-distance migration in Congressional Districts. In summary, our results suggest that the effects of neighboring district ideology are strongest in districts with the most short-distance migration, exactly as our theory would predict.

It is possible that our results here are driven by legislators from primarily urban legislative districts. We test this possibility in the supplemental appendix and find that legislators from both rural and urban districts respond to the ideology of their neighboring districts.

We contacted Census Bureau survey statistician Kin Koerber, who is a specialist in migration statistics and agreed to be referenced for this paper on these points. Mr. Koerber confirmed on more than one occasion that district-to-district migration cannot be tracked, aggregated, or measured with current Census data. Mr. Koerber provided the following document on measuring migration using the ACS data in which the migration data team specifically requests that previous address information begin to be collected (section 1.2) moving forward: http://www.census.gov/acs/www/Downloads/methodology/content_test/P3_Residence_1_Year_Ago.pdf.

For the rest of this section, we refer to residents who changed counties in the year prior to receiving the ACS as “short-distance migrants.”

West Virginia’s 1st Congressional District has been excluded. For that district, there were more respondents indicating movement from a previous address than there were in the total estimated population.

To help the multilevel models achieve convergence, each of our continuous covariates were standardized.

References

Agresti, A. (2007). An introduction to categorical data analysis (Vol. 423). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Bertelli, A. M., & Carson, J. L. (2011). Small Changes, big results: Legislative voting behavior in the presence of new voters. Electoral Studies, 30(1), 201–209.

Bishop, B. (2009). The big sort: Why the clustering of like-minded America is tearing us apart. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcour.

Blackwell, M., Honaker, J., & King, G. (2010). “Multiple overimputation: A unified approach to measurement error and missing data.” Annual Meeting of the Society for Political Methodology.

Brady, D. W., Han, H., & Pope, J. C. (2007). Primary elections and candidate ideology: Out of step with the primary electorate? Legislative Studies Quarterly, 32(1), 79–105.

Canes-Wrone, B., Brady, D. W., & Cogan, J. F. (2002). Out of step, out of office: Electoral accountability and house members voting. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 127–140.

Cantor, DM., & Herrnson, PS. (1997). Party Campaign Activity and Party Unity in the US House of Representatives. Legislative Studies Quarterly pp. 393–415.

Carsey, T. M., & Harden, J. J. (2010). New measures of partisanship, ideology, and policy mood in the American states. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 10(2), 136.

Carson, J. L., Koger, G., Lebo, M. J., & Young, E. (2010). The electoral costs of party loyalty in Congress. American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 598–616.

Cox, Gary W., & McCubbins, Mathew D. (1993). Legislative Leviathan: Party Government in the House. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cox, GW., & McCubbins, MD. (2005). Setting the agenda: Responsible party government in the US House of Representatives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crespin, M. H., Rohde, D. W., & Vander Wielen, R. J. (2013). Measuring variations in party unity voting: An assessment of agenda effects. Party Politics, 19(3), 432–457.

Fenno, R. F. (2007). Congressional travels: Places, connections and authenticity. New York: Longman.

Griffin, J. D. (2006). Electoral competition and democratic responsiveness: A defense of the marginality hypothesis. Journal of Politics, 68(4), 909–919.

Harden, J. J., & Carsey, T. M. (2012). Balancing constituency representation and party responsiveness in the US Senate: The conditioning effect of state ideological heterogeneity. Public Choice, 150(1), 137–154.

Kam, C. J. (2009). Party discipline and parliamentary politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Layman, GC., & Carsey, TM. (2002). Party polarization and “conflict extension” in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 786–802.

Layman, G. C., Carsey, T. M., Green, J. C., Herrera, R., & Cooperman, Rosalyn. (2010). Activists and conflict extension in American party politics. American Political Science Review, 104(2), 324–346.

Masket, S. E. (2007). It takes an outsider: Extralegislative organization and partisanship in the California Assembly, 1849–2006. American Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 482–497.

McCann, J. A. (1995). Nomination politics and ideological polarization: Assessing the attitudinal effects of campaign involvement. The Journal of Politics, 57(01), 101–120.

McGhee, E., Masket, S., Shor, B., Rogers, S., & McCarty, Nolan. (2014). A Primary Cause of Partisanship? Nomination Systems and Legislator Ideology. American Journal of Political Science, 58(2), 337–351.

Meinke, S. R. (2012). Party Size and Constituency Representation: Evidence from the 19th-Century US House of Representatives. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 37(2), 175–197.

Nyhan, B., McGhee, E., Sides, J., Masket, S., & Greene, Steven. (2012). One Vote Out of Step? The Effects of Salient Roll Call Votes in the 2010 Election. American Politics Research, 40(5), 844–879.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (1991). Patterns of Congressional Voting. American Journal of Political Science, 35, 228–277.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2007). Ideology and Congress. Piscataway, New Jersey: Transaction Press.

Ravenstein, EG. (1885). The Laws of Migration. Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 48, 167–235.

Roberts, J. M., & Smith, S. S. (2003). Procedural Contexts, Party Strategy, and Conditional Party Voting in the US House of Representatives, 1971–2000. American Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 305–317.

Snyder, J. M, Jr, & Ting, M. M. (2003). Roll calls, party labels, and elections. Political Analysis, 11(4), 419–444.

Acknowledgments

Justin H. Kirkland is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Houston. R. Lucas Williams is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at the University of Houston. We are grateful to Jonathan Slapin, Phillip Paolino, and the anonymous reviewers for feedback on our manuscript. All errors are our own. Correspondence regarding this work can be addressed to jhkirkland@uh.edu. Supplemental appendices and replication materials can be found at jhkirkla.wordpress.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kirkland, J.H., Williams, R.L. Representation, neighboring districts, and party loyalty in the U.S. Congress. Public Choice 165, 263–284 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0307-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0307-x