Abstract

Violence in the home, including partner violence, child abuse, and elder abuse, is pervasive in the United States. An informatics approach allowing automated analysis of administrative data to identify domestic assaults and release timely and localized data would assist preventionists to identify geographic and demographic populations of need and design tailored interventions. This study examines the use of an established national dataset, the NEMSIS 2019, as a potential annual automated data source for domestic assault surveillance. An algorithm was used to identify individuals who utilized emergency medical services (EMS) for a physical assault in a private residence (N = 176,931). Descriptive analyses were conducted to define the identified population and disposition of patients. A logistic regression was performed to predict which characteristics were associated with consistent domestic assault identification by the on-scene EMS clinician and dispatcher. The sample was majority female (52.2%), White (44.7%), urban (85.5%), and 21–29 years old (24.4%). A disproportionate number of those found dead on scene were men (74.5%), and female patients more often refused treatment (57.8%) or were treated and then released against medical advice (58.4%). Domestic assaults against children and seniors had higher odds of being consistently identified by both the dispatcher and EMS clinician than those 21–49, and women had lower odds of consistent identification than men. While a more specific field to identify the type of domestic assault (e.g., intimate partner) would help inform specialized intervention planning, these data indicate an opportunity to systematically track domestic assaults in communities and describe population-specific needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Domestic assault, or violent assaults occurring between members of the same household, family members or intimate partners, occurs throughout the life course and across communities in the U.S. In the U.S., 60% of simple and aggravated assaults occur in private residences in 2021 (FBI, 2022). Nearly half of adult women (41%), one fourth of adult men, and one third of transgender adults experience intimate partner violence (IPV) in their lifetimes (Langenderfer-Magruder et al., 2016; Leemis et al., 2022). One in 7 children experiences child abuse and neglect and 1 in 10 seniors experiences abuse in the home (CDC, 2021, 2022). IPV (Campbell, 2002), child abuse and neglect (Norman et al., 2012), and elder abuse (Yunus et al., 2019) have been linked to numerous negative individual-level health outcomes, and the burden of violence extends beyond the home. IPV’s estimated lifetime cost in the U.S. is $4.7 trillion, 59% of which are medical costs and 37% of which are paid for using public funds (Peterson et al., 2018). The total annual U.S. cost of child abuse and neglect is estimated at $161 billion, and lifetime medical expenses average around $52,000 per child (Fang et al., 2012). While the cost of physical violence against seniors has not yet been estimated, financial elder abuse alone is estimated to cost $3.4 billion per year (MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2013).

Communities responding to the burden of domestic assaults require localized data about the distribution, severity, and cost of domestic assault to develop effective interventions and identify populations that have the most need. Two nationally representative datasets are available to estimate victimization in the U.S.: the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) and the National Survey of Victims of Crime (NCVS). The NISVS is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance system that surveys non-institutionalized U.S. adults about lifetime and past year intimate partner and sexual violence victimization and its health impacts using random-digit dialing (Kresnow et al., 2022). The NISVS began collecting data in 2010 and captures an in-depth picture of victimization types, perpetrator-victim relationships, and the impacts of violence and report estimates at the national level (Kresnow et al., 2022). The Bureau of Justice Statistics manages the NCVS surveillance system, an annual survey of U.S. household members ages 12 and older that started in 1973. Participants are interviewed about their experience with a range of crimes and their use of the criminal justice system (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2021). While both national datasets offer an opportunity to examine domestic assaults and help-seeking behavior after victimization throughout the life course, the data are unavailable at a local level, and there is a time lag in their release, limiting their utility to inform current local intervention needs for policy makers and systems that respond to violence in the home.

Local domestic assault estimates predominantly rely on samples drawn from criminal justice, medical, and social services settings. Local police data, for example, are available through the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), allowing public users to access local estimates through an online surveillance portal (AbiNader et al., 2023; FBI, 2022). While these data sources may accurately capture victims with a help-seeking propensity, it is likely that they fail to capture the total prevalence of domestic assaults. Less than half of women experiencing IPV report it to the police (44%) (Holliday et al., 2020), and calling the police has been linked to more injurious IPV (Ogbonnaya et al., 2021). Examining racial differences, Holliday and colleagues (2020) found that Black women had higher rates of reporting than White women and that Latina and White women had similar rates of reporting. However, Black and Latina women were more likely to report IPV to law enforcement if it resulted in injury (Holliday et al., 2020). Similarly, those experiencing more injurious violence are more likely to seek emergency medical care (Duterte et al., 2008), limiting the completeness of emergency room data. Moreover, previous studies suggest that only about 14% of assault victims access emergency medical services (Kaylen & Pridemore, 2015). Child and adult protective service samples overrepresent children and adult victims of color, generating data samples with potential racial bias (Drake et al., 2011; Lachs et al., 1997). Community-based domestic violence services serve predominantly cis-heterosexual women, thereby underestimating the prevalence among LGBTQIA individuals and men (Lyon et al., 2008). In rural communities, barriers to accessing criminal justice, medical, and social services such as transportation may also result in a lack of rural representation in datasets (Grama, 2000; Peek-Asa et al., 2011). Despite these limitations, service population data can offer insight into the demographics of individuals using local services, the types and context of violence experienced, the type and efficacy of interventions, and the relative spatial distribution of need and services. Understanding the burden of disease at the local level is imperative to allow policy makers to allocate funding and interventions to the most needed areas and to track the impacts of those interventions.

An informatics approach to understanding the health burden of domestic assaults that allows automated analysis of administrative data to release more timely and localized data would support prevention and response resources. A data-driven public health surveillance approach has long been called for as a necessary tool to track and understand the prevalence and etiology of injury and the effectiveness of interventions (Thacker & Berkelman, 1988). Public health surveillance requires that data are translated for individuals that design policies and programs in order to promptly respond to changes in the burden and context of a disease (Thacker & Berkelman, 1988). Surveillance must be ongoing and timely in order to actively and efficiently respond to problems (Jajosky & Groseclose, 2004; Thacker & Berkelman, 1988). Moreover, this type of systematic data collection could also track how victims move through systems and the effectiveness of interventions. This latter information can be used for routine system evaluation to constantly improve responses to victims of violence.

Here, using data from the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS), we estimate the number of identified incidents of domestic assaults that occurred in personal residences and required an emergency medical service (EMS) response in the U.S. We describe the epidemiologic characteristics of these complaints in terms of the patient’s age, sex, race, and ethnicity, by month of the year, day of the week and by time of day, and by census region. In doing so, we create an algorithm to identify EMS responses to incidents of domestic assaults using NEMSIS data. We describe the strengths and limitations of this novel approach with the expectation that analytical methods can be developed for routine use with local or regional EMS administrative data for public health surveillance of domestic assaults.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a retrospective analysis using publicly available 2019 NEMSIS research data. NEMSIS is a product of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Office of Emergency Medical Services and is the largest repository of de-identified EMS records in the U.S., with over 34 million events from more than 10,000 EMS agencies (Dawson, 2006; Hanlin et al., 2022). For this study we used the most recent NEMSIS dataset (2019 version) available (https://nemsis.org/using-ems-data/request-research-data/) prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to avoid the well-documented impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home orders on many aspects of community interaction, arguably affecting domestic assaults in particular (Kourti et al., 2023) and on EMS response patterns that potentially affected responses to domestic assault calls (Al Amiry & Maguire, 2021; Handberry et al., 2021). We believe the 2019 NEMSIS data most accurately reflects the true patterns of domestic assault exclusive of the influence of COVID-19. To our knowledge, this is the first use of NEMSIS data to describe and measure domestic assaults. NEMSIS data are released as a de-identified, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act exempt, publicly available dataset, hosted by the University of Utah with local Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight (https://nemsis.org/using-ems-data/). Therefore, no further IRB review was sought for these analyses.

Inclusion of Records

Records were excluded if the Disposition (eDisposition.12) of the response was listed as Canceled (codes 4,212,007, 4,212,009, 4,212,011), Standby-No Services or Support Provided (code 4,212,039), or Transport Non-patient (code 4,212,043) or eResponse.05 was coded as Interfacility Transport (code 2,205,003) or Medical Transport (code 2,205,007).

Measures

EMS activations for which the dispatcher reported domestic assaults were identified if the NEMSIS eDispatch.01 variable was listed as Assault or Stab/Gunshot Wound/Penetrating trauma and the NEMSIS eScene.09 variable was listed as Private Residence. To code patients as having experienced domestic assaults based on clinical data reported by the EMS clinical on scene, ICD10 coded data from the eInjury.01, eSituation.11 and eSituation.12 variables were used. The eInjury.01 variable records the cause of treated injuries, and the eSituation variables record the EMS clinician’s overall impression of the encounter. Patients treated in private residences were coded as having experienced domestic assault if the eSituation variables reported Neglect or Abuse or the eInjury.01 variable included codes for Neglect, Abuse, or Assault.

The eDisposition.12 variable indicated the patient’s final disposition, such as treated on scene, transported to hospital, or died on scene. Patient acuity is categorized by EMS clinicians using nationally standardized definitions for “Critical,” “Emergent,” and “Lower Acuity,” based on the Patient Acuity Definitions defined by the NHTSA National EMS Core Content and which follows the Model of Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2005). The NEMSIS eSituation.13 variable reports the responding EMS clinicians’ rating of the patient’s condition on scene. The eSituation.13 variable adds a fourth category “Dead without Resuscitation Efforts” to these three acuity categories. The eSituation.13 variable has missing values, particularly when the eDisposition.12 variable was coded as “Patient evaluated, no treatment or transport required” or “Patient treated and released per protocol.” Thus, when eSituation.13 had missing values and eDsiposition.12 was coded as “Patient evaluated, no treatment or transport required” or “Patient treated and released per protocol,” the patient was coded as Lower Acuity for the purposes of analyses.

Sociodemographic Data

NEMSIS variables were used to categorize the age (ageyears), sex (ePatient.13), and race and ethnicity (ePatient.14) of the patient. The CensusDivision variable was used to define the U.S. region where the incident occurred.

Statistical Analyses

Patients were coded as having experienced domestic assault based on EMS dispatch data and based on the EMS clinicians’ on-scene evaluation. Descriptive statistics were used to describe patient sociodemographic characteristics and acuity based on EMS clinician data. Sensitivity analyses were run on the sociodemographic and patient acuity data to compare results when EMS clinician data were used to define domestic assaults and when EMS dispatch data were used to define domestic assaults. No substantive differences were found in magnitude nor direction (Online Resource 1).

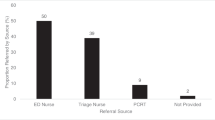

Cross tabulations were used to assess the agreement between the EMS dispatch data and the EMS clinician for classifying patients as having experienced domestic assault. EMS dispatchers receive information from a variety of people with varying levels of knowledge about an incident, and dispatch data reflect the content of what they are told. Thus, EMS dispatch reports are highly variable, dependent upon the quality of information provided to the dispatcher, and with a significant frequency of discordance with the true clinical situation on scene (Bohm & Kurland, 2018; Reckdenwald et al., 2017). By contrast, the on-scene EMS clinician is able to assess the true context of the emergency and connect with emergency department clinicians to discuss any abuse situations. Therefore, it is likely that the EMS clinical report more accurately represents the incident than the dispatcher report. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value for the dispatch data predicting the EMS clinician report data were calculated. Logistic regression analyses were used to determine whether patient characteristics and time of day were associated with the EMS clinician evaluation agreeing with the dispatch information. For all EMS activations that were classified as domestic assaults based on the dispatch data, activations were coded as Agree if the EMS clinician data also identified a domestic assault and were coded as Disagree if the EMS clinician data did not identify a domestic assault. Among patients classified as having experienced domestic assault using the EMS clinician data, descriptive analyses were conducted for the patient acuity, final disposition of the EMS response, and patient socio-demographics.

Results

In total 12,426,669 EMS activations were dispatched to private residences in 2019. Based on dispatch data, 218,595 EMS activations were classified as being for domestic assaults, while EMS clinician data identified 176,931 patients who had experienced domestic assaults. The sensitivity and specificity for the dispatch data predicting that the EMS clinician data would identify domestic assaults were 62% and 99%, respectively, and the positive predictive value was 51%.

Table 1 reports on the analyses of predictors of the EMS clinician identification of domestic assaults agreeing with the dispatch data. Compared to the patient age being < 21 years, agreement was positively associated with the patient’s age being above 65 or not reported and negatively associated with age less than 50. Female sex being reported for the patient was associated with a lower odds of agreement, and sex not being reported was associated with higher odds of the two data sources agreeing. Patient race and ethnicity were not associated with the two data sources agreeing. The odds of agreement between the data sources were substantially higher for EMS dispatches occurring between 9 a.m. and 7 p.m., as compared to dispatches occurring between midnight and 1 a.m.

Table 2 reports on the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients classified as having experienced domestic assaults by the EMS clinician. EMS activations for domestic assaults were highest during the summer. Overall, the patients were majority White, urban, 21–29 years old, and from the South Atlantic region and were relatively balanced across the sexes: 47% were male, 52% were female, and 0.57% did not have a sex listed in the data. Female patients were more likely to be in the age range of 21 to 39 years of age. The distribution of patients by race and ethnicity, Census Division, urbanicity, and month of the year of the incident did not vary by sex.

Table 3 reports on the patient acuity and the final disposition of the patient. In total, patient acuity data was missing from 21.7% of patients: 22.0% for male and 21.1% for female patients. But among those with data, a greater percentage of male patients had acuity grades of Emergent, Critical, and Found dead without resuscitation efforts than female patients. The final disposition of male patients was more likely to be “Patient died at scene” and “Patient treated and transferred or transported” than for female patients. Female patients were more likely to be listed as “Patient evaluated no treatment or transport required,” “Patient refused evaluation,” “Patient treated and released AMA,” or “Patient treated and released per protocol” than male patients.

Discussion

This paper used a novel approach to demonstrate how administrative data may be leveraged to develop local, automated surveillance systems to track domestic assaults. The results suggest that data provided by the dispatch record is not a sufficiently sensitive screen for identifying patients who had experienced domestic assault. Instead, data reported by the EMS clinician in the eInjury and eSituation variables should be used to identify patients who have experienced domestic assault. Analyses of the eInjury and eSituation variables are more challenging than analyses of the eDispatch variable but can be automated and offer a promising new approach to surveillance of domestic assaults.

The NEMSIS data mirrors trends in national law enforcement data on assaults. The NIBRS similarly reports that the largest age group experiencing simple and aggravated assaults are in their 20s, and more White individuals experience assault (FBI, 2022). Like the NEMSIS data, NIBRS estimates that more men die of fatal assaults than women (FBI, 2022). Recent NCVS data report that urban areas experience higher rates of assault incidents than suburban and rural areas, similar to the NEMSIS service-use estimates (Thompson et al., 2022). These parallel findings suggest that NEMSIS may be an excellent system to leverage to produce local estimates of domestic assaults.

Women were less likely to be consistently identified as domestic assault victims in the EMS data. More research is needed to determine if the definitions of domestic assault are not accurately capturing women’s experiences of violence in the home or if this points to women being more likely to recant an account of violence due to safety concerns or to systemic barriers (Bennett et al., 1999; Epstein & Goodman, 2018). More work is needed to determine if the finding that women more frequently refuse care is related to a lack of gender-responsive care, gendered perceptions of criminal legal systems, or due to gendered differences in the types of assault experienced, as women are more likely to experience simple assault than men (FBI, 2022).

Findings from the NEMSIS data indicate an opportunity to systematically track domestic assaults in communities and describe population-specific needs. The predictive validity analyses suggest that while the dispatch data is good at predicting non-domestic assault cases (specificity, 99%), its identification of domestic assaults could be improved (sensitivity, 62%; positive predictive value, 51%). Although the findings from the regression model suggest that dispatch data may be good at capturing elder abuse and abuse towards children and youth, it appears less good at capturing violence in middle age. In sum, these analyses suggest that any automated surveillance system would need to use the more complex EMS clinician data than the simpler dispatch data. Future implementation studies may also examine and test trainings on domestic assault for dispatchers to improve accurate reporting (Reckdenwald et al., 2017). As occurs in many administrative datasets, the missingness in the race/ethnicity and acuity data presents challenges for identifying groups at increased risk of violence and informing interventions that are appropriate for intersectional identities. While this causes limitations in public health surveillance, this approach would still likely improve upon current methods. Moreover, should NEMSIS be formally expanded into a surveillance tool, its expanded use in this way may encourage less missing data in years to come.

The primary strength of NEMSIS data is that they provide a well-documented census of health complaints requiring an EMS response across 47 U.S. states. NEMSIS has established standardized variables for which data need to be reported by all EMS, and these required variables were used to create our domestic assault case–finding algorithm. The domestic assault case–identification strategy relies on ICD 10 codes entered into these specific data fields by EMS responders. Much of the data is supplied to NEMSIS by third-party companies that provide data services to EMS companies and health care systems. The data entry systems provided by these third-party companies vary, and this may influence the ICD 10 coding options available to EMS personnel; thus, the quality of the ICD 10 data may vary by provider and between regions these companies operate in. However, these data service companies could begin selling “public health surveillance as service” data products by city and region and develop a sustainable model for routine analyses. In addition, if NEMSIS had the capacity to institute Data Use Agreements with county health departments that allowed access to data with county identifiers, NEMSIS EMS data could be routinely analyzed locally for local public health surveillance purposes.

A limitation of the informatics approach demonstrated here is that the coding schema do not make use of narratives and text notes created by EMS personnel. As such, the reliance on ICD 10 codes may result in an undercount of incidents of domestic assaults, particularly those that occurred outside the home or between partners or family members that do not currently cohabitate. However, machine learning for natural language processing applied to EMS narrative notes could supplement the ICD 10-based case-finding algorithm and increase the sensitivity of identifying incidents of domestic assaults from EMS data, as has been used elsewhere with fatal assault data (Kafka et al., 2023). Further research is needed to determine the feasibility of automated processing of EMS notes to identify domestic assaults and whether increased sensitivity comes at the cost of reduced specificity. Despite these limitations, the NEMSIS data demonstrate a unique opportunity to expand an existing data system to better track domestic assaults locally.

Conclusion

NEMSIS data represent an opportunity to estimate the health burden of domestic assaults in communities. The approach to analyzing administrative data described here provides the foundation for an automated, routine public health surveillance of domestic assaults, particularly those resulting in injury. Such surveillance systems would support the planning and allocation of resources for treatment and social and mental health services and would support targeted community-level and institutional prevention intervention strategies.

Data Availability

EMS data are available by request at: https://nemsis.org/

References

AbiNader, M. A., Graham, L. M., & Kafka, J. M. (2023). Examining intimate partner violence-related fatalities: Past lessons and future directions using U.S. National Data. Journal of Family Violence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00487-2

Al Amiry, A., & Maguire, B. J. (2021). Emergency medical services (EMS) calls during COVID-19: Early lessons learned for systems planning (a narrative review). Open Access Emergency Medicine: OAEM, 13, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAEM.S324568

Bennett, L., Goodman, L., & Dutton, M. A. (1999). Systemic obstacles to the criminal prosecution of a battering partner: A victim perspective. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(7), 761–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626099014007006

Bohm, K., & Kurland, L. (2018). The accuracy of medical dispatch—A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 26(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-018-0528-8

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021). National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/ncvs#18s6hz

Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet, 359(9314), 1331–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Preventing child abuse & neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/prevention/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Preventing elder abuse. https://www.cdc.gov/elder-abuse/about/index.html

Dawson, D. E. (2006). National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS). Prehospital Emergency Care, 10(3), 314–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903120600724200

Drake, B., Jolley, J. M., Lanier, P., Fluke, J., Barth, R. P., & Jonson-Reid, M. (2011). Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using National Data. Pediatrics, 127(3), 471–478. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1710

Duterte, E. E., Bonomi, A. E., Kernic, M. A., Schiff, M. A., Thompson, R. S., & Rivara, F. P. (2008). Correlates of medical and legal help seeking among women reporting intimate partner violence. Https://Home Liebertpub Com/Jwh, 17(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1089/JWH.2007.0460

Epstein, D., Goodman, L. A., & I. (2018). Discounting women: Doubting domestic violence survivors’ credibility and dismissing their experiences. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 167(2), 399–462.

Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S., & Mercy, J. A. (2012). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(2), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006

FBI. (2022). Crime Data Explorer. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/home

Grama, J. L. (2000). Women forgotten: Difficulties faced by rural victims of domestic violence. American Journal of Family Law, 14(3), 173.

Handberry, M., Bull-Otterson, L., Dai, M., Mann, N. C., Chaney, E., Ratto, J., Horiuchi, K., Siza, C., Kulkarni, A., Gundlapalli, A. V., & Boehmer, T. K. (2021). Changes in emergency medical services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, January 2018-December 2020. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 73(Suppl 1), S84–S91. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab373

Hanlin, E. R., Chan, H. K., Hansen, M., Wendelberger, B., Shah, M. I., Bosson, N., Gausche-Hill, M., VanBuren, J. M., & Wang, H. E. (2022). Epidemiology of out-of-hospital pediatric airway management in the 2019 national emergency medical services information system data set. Resuscitation, 173, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.01.008

Holliday, C. N., Kahn, G., Thorpe, R. J., Shah, R., Hameeduddin, Z., & Decker, M. R. (2020). Racial/ethnic disparities in police reporting for partner violence in the National Crime Victimization Survey and survivor-led interpretation. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7(3), 468–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00675-9

Jajosky, R. A., & Groseclose, S. L. (2004). Evaluation of reporting timeliness of public health surveillance systems for infectious diseases. BMC Public Health, 4(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-4-29

Kafka, J. M., Fliss, M. D., Trangenstein, P. J., Reyes, L. M., Pence, B. W., & Moracco, K. E. (2023). Detecting intimate partner violence circumstance for suicide: Development and validation of a tool using natural language processing and supervised machine learning in the National Violent Death Reporting System. Injury Prevention, 29(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip-2022-044662

Kaylen, M., & Pridemore, W. A. (2015). Serious assault victim and incident characteristics associated with police notification and treatment in emergency rooms in rural, suburban, and urban areas. International Criminal Justice Review, 25(4), 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057567715597299

Kourti, A., Stavridou, A., Panagouli, E., Psaltopoulou, T., Spiliopoulou, C., Tsolia, M., Sergentanis, T. N., & Tsitsika, A. (2023). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 24(2), 719–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211038690

Kresnow, M., Smith, S. G., Basile, K. C., & Chen, J. (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 methodology report. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs/nisvsMethodologyReport.pdf

Lachs, M. S., Williams, C., O’Brien, S., Hurst, L., & Horwitz, R. (1997). Risk factors for reported elder abuse and neglect: A nine-year observational cohort study. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.469

Langenderfer-Magruder, L., Whitfield, D. L., Walls, N. E., Kattari, S. K., & Ramos, D. (2016). Experiences of intimate partner violence and subsequent police reporting among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adults in Colorado: Comparing rates of cisgender and transgender victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(5), 855–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514556767

Leemis, R. W., Friar, N., Khatiwada, S., Chen, M. S., Kresnow, M., Smith, S. G., Caslin, S., & Basile, K. C. (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 report on intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/nisvs/documentation/NISVSReportonIPV_2022.pdf

Lyon, E., Lane, S., & Menard, A. (2008). Meeting survivors’ needs: A multi-state study of domestic violence shelter experiences, final report (225025). U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/225025.pdf

MetLife Mature Market Institute. (2013). Broken trust: Elders, family and finances. https://ltcombudsman.org/uploads/files/issues/mmi-elder-financial-abuse.pdf

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2005). National EMS Core Content (DOT HS 809 898). Retrieved August 7, 2023, from https://www.ems.gov/assets/National_EMS_Core_Content.pdf

Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 9(11), e1001349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

Ogbonnaya, I. N., AbiNader, M. A., Cheng, S. Y., Jiwatram-Negrón, T., Bagwell-Gray, M., Brown, M. L., & Messing, J. T. (2021). Intimate partner violence, police engagement, and perceived helpfulness of the legal system: Between-and-within-group analyses by women’s race and ethnicity. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 81(1), 714828. https://doi.org/10.1086/714828

Peek-Asa, C., Wallis, A., Harland, K., Beyer, K., Dickey, P., & Saftlas, A. (2011). Rural disparity in domestic violence prevalence and access to resources. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(11), 1743–1749. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2891

Peterson, C., Kearns, M. C., McIntosh, W. L. K. W., Estefan, L. F., Nicolaidis, C., McCollister, K. E., Gordon, A., & Florence, C. (2018). Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(4), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2018.04.049

Reckdenwald, A., Nordham, C., Pritchard, A., & Francis, B. (2017). Identification of nonfatal strangulation by 911 dispatchers: Suggestions for advances toward evidence-based prosecution. Violence and Victims, 32(3), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-15-00157

Thacker, S. B., & Berkelman, R. L. (1988). Public health surveillance in the United States. Epidemiologic Reviews, 10(1), 164–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036021

Thompson, A., Tapp, S. N., & BJS Statisticians. (2022). Criminal Victimization, 2021 (NCJ 305101; BJS Bulletin). U.S. Department of Justice. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv21.pdf

Yunus, R. M., Hairi, N. N., & Choo, W. Y. (2019). Consequences of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review of observational studies. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 20(2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017692798

Funding

Dr. Lo was supported by a grant from the Davee Foundation. Dr. Rundle was supported by the Columbia Center for Injury Science and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant no. R49CE003094. There are no other funding sources to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This study was exempt from IRB review by the Columbia University IRB.

Informed Consent

This study utilizes deidentified administrative data from NEMSIS. The authors were not involved in data collection or abstraction.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

AbiNader, M.A., Rundle, A.G., Park, Y. et al. Population-Level Surveillance of Domestic Assaults in the Home Using the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS). Prev Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-024-01683-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-024-01683-w