Abstract

This study delves into the crucial topic of turnover intention among U.S. Federal Employees, shedding light on the workplace factors that play a pivotal role in mitigating this issue. Through the utilization of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analyses, the study meticulously examines various workplace contextual factors and their impact on turnover intention. The standout finding of the study underscores the paramount importance of opportunities for growth and development (Factor 4) in reducing turnover intention. This emphasizes the significance of investing in employees’ professional advancement and creating avenues for them to expand their skills and progress in their careers. Moreover, the study brings to the forefront additional factors that contribute to decreased turnover intention, such as longer tenure, higher salary, gender (with females exhibiting lower turnover intention), and age. These insights not only provide a nuanced understanding of the dynamics at play but also offer actionable strategies for organizations to address turnover concerns effectively. By identifying these key factors, the study equips HR professionals and decision-makers with valuable guidance for implementing tailored HRM practices aimed at curbing turnover and fostering a more stable and satisfied workforce within the U.S. Federal sector. Ultimately, these findings have the potential to drive tangible improvements in employee retention and organizational performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employee turnover imposes significant costs on organizations. Upon an employee’s resignation, the organization must navigate a protracted process involving recruiting, hiring, and training a replacement—an undertaking accompanied by substantial tangible expenses (Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008; Tziner & Birati, 1996). In addition to the quantifiable costs linked to this replacement cycle, voluntary turnover brings about intangible costs including loss of knowledge, decreased customer satisfaction, disruptions in organizational performance, and diminished morale among remaining employees (Dess & Shaw, 2001; Felps et al., 2009; Hausknecht et al., 2009). Considering these multifaceted costs, it is understandable that scholars and practitioners have given particular attention to comprehending the reasons behind employee departures since the early 20th century (Hom et al., 2017).

Since the pioneering work of March and Simon in 1958, researchers have strived to predict voluntary turnover using various models. A recent meta-analysis of studies on voluntary turnover studies (Holtom et al., 2008) show that more than 50 broad antecedents have been recognized as scientifically valuable predictors of voluntary turnover. While factors such as personality, job satisfaction, job characteristics, and job stress have traditionally been extensively studied in turnover research, the organizational context, including aspects such as organizational culture and employees’ working environment, has only recently garnered recognition from researchers (Holtom et al., 2008; Hom et al., 2017). The term “context” can be defined as “stimuli and phenomena that surround and exist in the environment external to the individual” (Mowday & Sutton, 1993).

Given the pivotal role of context in studies of organizational behavior, it is noteworthy that researchers have not adequately delved into the impact of contextual factors on voluntary turnover. Unlike existing turnover studies, which mainly focus on specific contextual factors like organizational justice (Hemdi & Nasurdin, 2007), trust (Jabeen & Isakovic, 2018), and organizational culture (Campbell & Im, 2016), this study undertakes a more comprehensive examination and endeavors to address a significant gap in the literature by examining the combined influence of various workplace characteristics on turnover intention. Through a comprehensive review of workplace contextual factors and their effects on turnover intention, this study aims to reduce undesired voluntary turnover by gaining a nuanced understanding of the broader organizational context.

Theoretical Backgrounds

Turnover is defined as the extent of individual movement across the membership boundary of a social system (Price, 1977, P. 3). When an employee decides to cross the membership boundary of an organization, it is termed voluntary turnover, whereas involuntary turnover occurs when an employer makes this decision, such as through firing or layoffs. This study specifically centers on voluntary turnover, with turnover intention serving as a proxy for this phenomenon. Turnover intention refers to an individual’s thoughts about leaving their current organization. Although turnover intention may not always lead to actual turnover, research suggests a substantial relationship between the two (Park & Shaw, 2013), with turnover intention frequently regarded as an alternative measure for actual turnover (Price, 2001). Indeed, turnover intention has emerged as a widely acknowledged proxy for actual voluntary turnover in studies conducted in both the public and private sectors (Bertelli, 2007; Caillier, 2011; Cho & Lewis, 2012; Cohen et al., 2016; Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008; Pitts et al., 2011).

Determinants of Voluntary Turnover

The cost of replacing a departing employee is estimated to be approximately twice their annual salary (Allen et al., 2010). This significant expense has motivated researchers’ efforts over the past century to understand the reasons behind employee departures (Hom et al., 2017). Resulting in over 1,500 academic studies, these investigations have identified 50 broad antecedents of voluntary turnover (Holtom et al., 2008). Determinants of voluntary turnover are typically categorized into external environmental, work-related organizational, and individual characteristic factors (Mobley et al., 1979). External environmental factors encompass perceived alternatives (such as job availability) and the unemployment rate (e.g., Anderson & Milkovich, 1980; Carsten & Spector, 1987; Fields, 1976; Lee et al., 2017). Research indicates a positive correlation between employees’ turnover and turnover intention with job availability and a negative correlation with the unemployment rate (Peters et al., 1981). Work-related organizational factors include various aspects like job satisfaction (Medina, 2012), development and growth opportunities (Weng et al., 2010), promotion (Yücel, 2012), pay (Irvine & Evans, 1995), perceived autonomy (Gillet et al., 2013), goal clarity (Davis & Stazyk, 2015), and job stress (Arshadi & Hayavi, 2013). In general, turnover or turnover intention tends to decrease when employees experience high job satisfaction, ample development and growth opportunities, increased promotion prospects, better compensation, greater autonomy, clearly defined goals, or minimal job stress (Griffeth et al., 2000). Individual characteristic factors encompass demographic variables such as gender (Sabharwal, 2015), education level (Lambert et al., 2001), tenure (Um & Harrison, 1998), race (Jones & Harter, 2004), age (Emiroğlu et al., 2015), and marital status (Kim et al., 2012). Typically, turnover or turnover intention tends to decrease when employees are female, less educated, long-tenured, white, older, or married (Griffeth et al., 2000).

Remarkably, the exploration of job turnover in public sector settings did not receive significant attention until the new millennium (Lee & Jimenez, 2011). Determinants of turnover for public employees have been identified across various areas, including job characteristics (Kim, 2012), human resource management practices (Tinti et al., 2017), person-organizational fit (Ballinger et al., 2016), and public service motivation (Bright, 2007).

Contextual Factor Studies

The organizational context has only recently garnered attention from turnover researchers, despite its significant impact on the occurrence and interpretation of organizational behavior (Rubenstein et al., 2018, p. 38). Traditionally, turnover researchers have focused on examining the effects of selected contextual factors on voluntary turnover, considering both the organizational context level and the person-context interface (Holtom et al., 2008; Rubenstein et al., 2018). Factors at the organizational context level that have captured turnover researchers’ attention include organizational support (Amarneh et al., 2021), engagement aggregated (Harter et al., 2003), organizational citizenship behavior (Mallick et al., 2014), organizational size (Guan et al., 2014), and diversity level (Choi, 2013). Generally, researchers have found that turnover or turnover intention decreases when employees experience high organizational support, exhibit high engagement, engage in organizational citizenship behaviors, work in larger organizations, and experience lower levels of diversity.

Person-context interface factors encompass elements such as offered rewards (Miao et al., 2013), organizational justice (George & Wallio, 2017), trust (Ellickson & Logsdon, 2001), and organizational culture (Egan, 2008). Researchers generally found that employees’ turnover or turnover intention decreases when employees are satisfied with rewards, experience justice and trust in their organization, or when a positive organizational culture (e.g., high-performing or learning culture) prevails.

Workplace and Demographic Factors

The study employed the Merit Principles Survey 2016 Data, providing a comprehensive perspective on various workplace aspects. Utilizing exploratory factor analysis, we grouped 20 workplace variables into four distinct factors. Further elaboration on the methodology of the factor analysis will be provided in the subsequent methods section. In this section, our focus shifts to proposing hypotheses centered around each of the identified factors and demographic variables, which will serve as focal points in our regression analyses.

Workplace Factors

Happy and Innovative Working Climate (Factor 1)

Studies suggest that when employees feel valued, their inclination to leave decreases (Mancuso et al., 2010). For example, expatriate educators are more inclined to stay in their current positions when they experience a positive work environment, characterized by recognition from both peers and management (Odland & Ruzicka, 2009). An innovative work environment encourages employees to explore fresh ideas, nurturing a heightened sense of psychological empowerment and job satisfaction (Hsu & Chen, 2017). As a result, an innovative work environment has been linked to a reduction in turnover intention (Yeun, 2014).

-

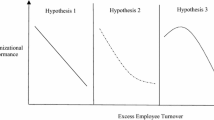

H1: Employees working in happy and innovative working climate tend to have a low level of turnover intention.

Feeling Valued and Trusted (Factor 2)

Employees who perceive low support are less likely to feel valued, and this has been linked to higher turnover, particularly in the retail sector (Shanock & Eisenberger, 2006). The sense of not feeling valued is identified as a significant factor contributing to voluntary turnover among U.S. child welfare employees (Nittoli, 2003). Conversely, when employees feel trusted, they experience higher levels of autonomy, fostering a desire to remain in their current organizations (Dirks & Skarlicki, 2004).

-

H2: When employees feel valued and trusted, they tend to have a low level of turnover intention.

Coworker Support and the Spirit of Camaraderie (Factor 3)

The relationship with coworkers and their support play a crucial role in determining organizational departure (Feeley, 2000). Employees who maintain positive relationships with coworkers and receive support from them exhibit lower turnover intentions (Young, 2015). Furthermore, a strong sense of camaraderie also diminishes turnover intentions (Lopes Morrison, 2005).

-

H3: When the spirit of camaraderie exists in an organization and employees receive support from coworker, they tend to have a low level of turnover intention.

Opportunities for Growth and Development (Factor 4)

Employees often depart organizations in pursuit of better growth and development opportunities (Quarles, 1994). For instance, the availability of career advancement prospects within current organizations fosters organizational commitment, potentially reducing turnover intentions among employees of public accounting firms (Nouri & Parker, 2013).

-

H4: When employees are satisfied with opportunities for growth and development, they tend to have a low level of turnover intention.

Demographic Factors

In this study, various demographic factors were included in regression analyses, revealing that turnover intention generally decreases due to certain demographic factors. Employees with longer tenure (Griffeth et al., 2000), a managerial status (Farris, 1969), higher salary (Sturman & Trevor, 2001), an older age (van Hooft et al., 2021), union membership or a teleworker status (Peters et al., 2004) typically exhibit lower levels of turnover intention. Conversely, turnover intention tends to increase among female employees (Karatepe et al., 2008), racial minorities (Xue, 2015), or those with higher levels of education (Choi, 2006).

-

H5-1: Employees with longer tenure show a lower level of turnover intention than employees with shorter tenure.

-

H5-2: Employees with higher managerial status show a lower level of turnover intention than employees with lower managerial status or non-managerial status.

-

H5-3: Employees with higher salary show a lower level of turnover intention than employees with lower salary.

-

H5-4: Employees with older age show a lower level of turnover intention than employees with younger age.

-

H5-5: Employees with a labor union membership show a lower level of turnover intention than employees without a labor union membership.

-

H5-6: Teleworkers show a lower level of turnover intention than non-teleworker.

-

H5-7: Female employees show a higher level of turnover intention than male counterparts.

-

H5-8: Employees with racial minority status show a higher level of turnover intention than employees with racial majority status.

-

H5-9: Employees with more education show a higher level of turnover intention than employees with less education.

Methods

This study employed ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses to investigate the influence of various workplace characteristics on turnover intention. Before conducting the OLS regression, exploratory factor analysis was utilized to uncover underlying factors among the 20 workplace variables. The data for this study were obtained from the Merit System Protection Board (MSPB)’s 2016 Merit Principles Survey (MPS) dataset ‘path 2.’ The sample consisted of 14,473 full-time civilian federal employees from 24 federal agencies, with a response rate of 38.7% for the dataset ‘path 2’ (Merit System Protection Board, 2016).

Major Variables

-

1)

Dependent variable

In this study, turnover intention was used as the dependent variable. While turnover intention may not perfectly align with actual turnover, a strong correlation between the two exists (Belkhir, 2009), and turnover intention has remained a key focus in turnover research (Cohen et al., 2016). Consequently, turnover intention frequently acts as a proxy measure for actual turnover in public administration literature (Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008), as well as in general turnover studies (Griffeth et al., 2000). In the 2016 MPS dataset, survey participants were asked to indicate their agreement level regarding the possibility of transitioning to a different occupation or line of work, with responses rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

-

2)

Independent variables

Various aspects of the workplace for federal employees served as independent variables in this study. Survey participants were asked to express their level of agreement on diverse workplace variables, rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To identify underlying dimensions among the 20 workplace variables, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted. In determining the number of factors, both eigenvalues and an eigenvalue scree plot were considered, as suggested by methodologists (Ferguson & Cox, 1993; Hayton et al., 2004). While one factor exhibited an eigenvalue greater than one (see Appendix Table 4), the eigenvalue scree plot indicated that the slope of the graph did not change significantly after the fourth factor (see Appendix Fig. 1). Following the scree test guideline (DeCoster, 1998; Yong & Pearce, 2013), it was recommended to retain all factors until the slope displayed minimal change. Consequently, this study identified four factors. Further details regarding the factor analysis can be found in Appendix. After the factor analysis, appropriate names were assigned to the extracted factors, acknowledging that the given names may not fully encapsulate the meaning of all component variables in each factor. The four attained factors, along with their component variables, are outlined below. The meanings of the component variables in each factor are detailed in Appendix Table 5.

-

Factor 1 (happy and innovative working climate): w9, w10, w11, w12, w14, w16, w17

-

Factor 2 (feeling valued and trusted): w2, w4, w5, w6, w7, w8

-

Factor 3 (coworker support and the spirit of camaraderie): w1, w3, w8, w13, w15

-

Factor 4 (opportunities for growth and development): w19, w20

The internal consistency or reliability of these four factors was evaluated by computing Cronbach’s alpha values. The Cronbach’s alpha values for all four factors fell within the range of 0.85 to 0.95 (refer to Appendix Table 5). According to the standards for internal consistency (Cronbach, 1951; Nunnally, 1978), a set of variables is considered to have satisfactory internal consistency or reliability when the Cronbach’s alpha value exceeds 0.7.

-

3)

Demographic variables

Nine demographic variables were utilized in this study, with numbers assigned to each variable as follows.

-

(1)

Years with current agency (d2)

1: 3 years or less, 2: 4 years or more,

-

(2)

Supervisory status (d4)

1: non-supervisor, 2: team leader, 3: supervisor, 4: manager, 5: executive

-

(3)

Union membership (d8)

0: non-union membership, 1: dues-paying union membership

-

(4)

Salary level (d10)

1: $74,999 or less, 2: $75,000-$99,999, 3: $100,000-$149,999, 4: $150,000 or more

-

(5)

Racial minority (d11)

0: non-minority, 1: minority

-

(6)

Gender (d12)

0: male, 1: female

-

(7)

Age group (d15)

1: 39 and under, 2: 40 and over

-

(8)

Education level (d16)

1: less than AA degree, 2: AA or BA degree, 3: graduate degree

-

(9)

Teleworker status (d18)

0: non-teleworker, 1: teleworker

Findings

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Mean values and standard deviations for both workplace and demographic variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 demonstrates that all correlations between workplace variables were significant and positive (p <.01), and likewise, all correlations between workplace variables and turnover intention were significant and negative (p <.01). In essence, turnover intention tends to decrease when employees express agreement or strong agreement with various workplace variables.

On average, federal employees did not demonstrate a high level of turnover intention (mean = 2.33 out of 5). Among the 20 workplace variables, the top five variables with which employees reported a high level of agreement were as follows: “I understand how I contribute to my agency’s mission” (w18, mean = 4.17), “My judgment is trusted and relied on at work” (w6, mean = 3.93), “I feel needed and depended on at work” (w4, mean = 3.88), “I like the quality of relationships I have with my coworkers” (w13, mean = 3.82), and “I feel comfortable being myself at work” (w17, mean = 3.78). It is worth noting that three of these variables (w18, w6, and w4) belong to Factor 2 (Feeling valued and trusted), while none are from Factor 4 (Opportunities for growth and development).

Conversely, the bottom five variables with which employees reported a low level of agreement were: “I am able to share my true thoughts and feelings at work” (w11, mean = 3.38), “I feel encouraged to try new things in my work” (w10, mean = 3.43), “I feel fully appreciated at work” (w9, mean = 3.44), “There is a culture of openness and support for new or different perspectives in my work unit” (w3, mean = 3.45), and “I feel cared about personally at work” (w12, mean = 3.46). Remarkably, four of these variables (w11, w10, w9, and w12) belong to Factor 1 (Happy and innovative working climate).

In Table 2, it is noted that, on average, survey participants remained in their current agencies for more than 4 years and held positions as team leaders or higher-level managers (mean = 2.25). Moreover, 15% of survey participants were union members, 33% were racial minorities, 42% were female, and 56% had the option to telework. Additionally, the average salary range fell between $75,000 and $150,000, the average age exceeded 40 years, and the typical education level was an associate’s (AA) or bachelor’s (BA) degree.

Workplace Variables, Demographics, and Turnover Intention

OLS regression analyses were conducted to determine which aspects of workplace characteristics contribute to decreased turnover intention and how demographic variables influence turnover intention. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was assessed during regression runs to detect potential multicollinearity issues arising from high correlations among workplace variables (see Table 1). Severe multicollinearity in regression analysis can compromise the statistical significance of each independent variable and render the results unreliable (Mansfield & Helms, 1982). However, the average VIF was found to be 2.79. According to suggested guidelines (Mansfield & Helms, 1982; Miles, 2005), multicollinearity is not a concern in regression analysis if the average VIF value is below 10.

The regression analyses began with only demographic variables. As depicted in Model 1 (Table 3), turnover intention decreased as salary increased (coefficient: − 0.170, p <.001), as employees aged (coefficient: − 0.094, p <.05), or when employees had the option to telework (coefficient: − 0.057, p <.05). Conversely, turnover intention increased if employees were union members (coefficient: 0.102, p <.01) or belonged to racial minorities (coefficient: 0.343, p <.001).

In Model 2 (Table 3), the four workplace variable factors (consisting of 20 variables) were incorporated with the demographic variables from Model 1. Notably, more demographic variables demonstrated significant effects on turnover intention in this model. In addition to the demographic variables that showed significant effects in Model 1, turnover intention decreased with longer tenure at current agencies (coefficient: − 0.096, p <.05), or among female employees (coefficient: − 0.059, p <.05). Conversely, turnover intention increased when employees held higher managerial status (coefficient: 0.051, p <.001). However, telework status and education level did not exhibit a significant effect on turnover intention.

In summary, out of the nine hypotheses regarding the effects of demographic variables, four were supported. Longer tenure (H5-1), higher salary (H5-3), and older age (H5-4) were associated with lower turnover intention, while racial minority status (H5-8) was linked to higher turnover intention. The effects of higher managerial status (H5-2), union membership (H5-5), and being female (H5-7) contradicted the predictions in the hypotheses. Unexpectedly, turnover intention increased when employees held higher managerial status or were union members, but decreased when employees were female. These unexpected findings will be discussed in the last section.

Regarding the effects of workplace variables, Model 2 revealed that three out of seven variables in Factor 1, three out of six variables in Factor 2, one out of five variables in Factor 3, and two out of two variables in Factor 4 had significant and negative effects on turnover intention. In other words, turnover intention significantly decreased when employees agreed or strongly agreed with those workplace variables. Overall, H1 and H2 were partially supported, H3 was not supported, and H4 was supported. Specifically, turnover intention significantly decreased when employees agreed or strongly agreed with Factor 4 (Opportunities for growth and development), whereas turnover intention was not affected by most variables in Factor 3 (Coworker support and the spirit of camaraderie). Among Factor 1 variables, turnover intention significantly decreased when employees agreed or strongly agreed with “I feel fully appreciated at work” (w9), “I feel comfortable talking to my supervisor about the things that matter to me at work” (w14), and “I feel comfortable being myself at work” (w17). For Factor 2 variables, turnover intention significantly decreased when employees agreed or strongly agreed with “My judgment is trusted and relied on at work” (w6), “I feel valued at work” (w7), and “I understand how I contribute to my agency’s mission” (w18).

Managerial Implications and Contributions to the Literature

This study identifies specific workplace factors that significantly influence turnover intention. Factor 4, which pertains to opportunities for growth and development, emerged as the most influential, indicating that investing in employee development can significantly reduce turnover intention. Conversely, Factor 3, related to coworker support and camaraderie, showed the least impact. This suggests that while social support is important, it may not be as influential in retaining employees as opportunities for professional growth. HR managers can use these findings to tailor their strategies and initiatives to address turnover. Emphasizing and enhancing opportunities for growth and development, such as training programs, career advancement paths, and skill-building opportunities, can be particularly effective in reducing turnover intention. Additionally, fostering a positive and innovative working climate (Factor 1) and ensuring employees feel valued and trusted (Factor 2) are also crucial for mitigating turnover intention.

This study also highlights the influence of demographic variables on turnover intention, including tenure, salary, age, race, managerial position, union membership, and gender. Understanding these demographic trends can help managers identify at-risk groups and implement targeted retention strategies. For example, recognizing that employees promoted to higher managerial positions may experience increased turnover intention due to heightened stress can guide the design of leadership development and support programs. In summary, this study underscores the importance of considering diverse workplace factors and demographic variables in understanding and addressing turnover intention. By leveraging these insights, organizations can develop targeted HRM practices that foster employee engagement, satisfaction, and retention.

The findings of this study make a significant contribution to the existing literature on turnover intention and workplace factors. The study fills a gap in the turnover literature by examining a wide array of organizational contextual factors that have not received significant attention previously. Unlike prior studies that often focused on specific factors such as organizational justice or culture, this research considers all contextual factors simultaneously. This holistic approach provides a comprehensive understanding of how various organizational elements interact to influence employee turnover intentions. By identifying which contextual factors have a more pronounced effect on turnover intention, the study offers valuable insights for organizations seeking to implement targeted retention strategies. For example, it highlights the significant impact of opportunities for growth and development (Factor 4) in reducing turnover intention. Understanding the relative importance of different factors can help organizations allocate resources more effectively to address turnover. While acknowledging the need for caution in interpreting findings, the study’s comprehensive approach to examining workplace factors and turnover intention enhances the generalizability of its results. By considering a diverse range of demographic variables and organizational contexts, this study provides insights that can be applicable across various industries and settings.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study aimed to identify workplace factors that could potentially alleviate turnover intention. Initial correlation analyses suggested a general inverse relationship between turnover intention and various workplace factors. However, further examination through Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analyses revealed that turnover intention was primarily influenced by Factor 4 (opportunities for growth and development), while Factor 3 (coworker support and camaraderie) had the least impact. Additional findings from the OLS regression analyses indicated that Factor 1 (a positive and innovative working climate) and Factor 2 (feeling valued and trusted) exerted a partial influence on turnover intention. These results emphasize the nuanced interplay of workplace elements in shaping employee attitudes toward turnover.

This study also delved into the impact of major demographic variables on turnover intention. Consistent with existing literature, employees with longer tenure, higher salaries, or older age exhibited a lower level of turnover intention, while those from racial minority backgrounds displayed a higher level of turnover intention. However, certain findings contradicted initial hypotheses. Contrary to the prediction in hypothesis H5-2, turnover intention increased when employees were promoted to higher managerial positions. Despite the general tendency for managers to stay in their current organizations due to higher investment (Farris, 1969), the study suggests that the heightened stress associated with elevated managerial roles, as indicated by Cavanaugh et al. (2000), may outweigh the perceived value of their investment, potentially leading to resignation. Additionally, turnover intention showed an unexpected increase among union members, contrary to the prediction in hypothesis H5-5. This finding supports an argument that union members typically experience lower job satisfaction than non-members (Hammer & Avgar, 2017). Despite the protective measures offered by unions (Freeman & Medoff, 1984), this study suggests that the reported lower job satisfaction among union members might contribute to their decision to resign. Contrary to the prediction in hypothesis H5-7, female employees exhibited a lower level of turnover intention than their male counterparts. This unexpected finding may be attributed to the observed higher job satisfaction among female employees, despite typically facing working conditions and rewards inferior to those of their male counterparts, as noted in some studies (e.g., Clark, 1997). The implication is that the presence of high job satisfaction among female employees serves as a mitigating factor against turnover intention, influencing their decision to remain in their current roles.

Despite the valuable contributions made by this study, it is essential to approach the interpretation of its findings with caution. Several factors warrant consideration. Firstly, while the focus on a limited number of workplace contextual factors and their impact on turnover intention is helpful, it is important to note that there is no universally agreed-upon set of workplace factors. The definition of workplace contextual factors may vary based on the survey questions posed. Conducting studies across diverse settings is crucial to establish more commonly agreed-upon workplace factors, enhancing the generalizability of findings. Secondly, the applicability of the findings in this study to public employees at different levels of government, such as state and local governments, or in various countries, remains uncertain. Given that the MPS data included only federal employees in the U.S., further research in different settings is necessary before extrapolating the findings to other contexts. Expanding the scope of investigation to include a broader range of participants will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between workplace contextual factors and turnover intention. Overall, this study advances our understanding of turnover intention by shedding light on the nuanced interplay of workplace elements and their impact on employee attitudes. Its findings offer actionable insights for HR practitioners and provide a foundation for future research in this field.

References

Allen, D. G., Bryant, P. C., & Vardaman, J. M. (2010). Retaining talent: Replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(2), 48–64.

Amarneh, S., Raza, A., Matloob, S., Alharbi, R. K., & Abbasi, M. A. (2021). The influence of person-environment fit on the turnover intention of nurses in Jordan: The moderating effect of psychological empowerment. Nursing Research and Practice, 2021, 668–860.

Anderson, J. C., & Milkovich, G. T. (1980). Propensity to leave: A preliminary examination of March and Simon’s model. Relations Industrielles, 35(2), 279–294.

Arshadi, N., & Hayavi, G. (2013). The effect of perceived organizational support on affective commitment and job performance: Mediating role of OBSE. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 739–743.

Ballinger, G. A., Cross, R., & Holtom, B. C. (2016). The right friends in the right places: Understanding network structure as a predictor of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(4), 535.

Belkhir, M. (2009). Board of directors’ size and performance in the banking industry. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 5(2), 201–221.

Bertelli, A. M. (2007). Determinants of bureaucratic turnover intention: Evidence from the Department of the Treasury. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(2), 235–258.

Bright, L. (2007). Does person-organization fit mediate the relationship between public service motivation and the job performance of public employees? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 27(4), 361–379.

Caillier, J. G. (2011). I want to quit: A closer look at factors that contribute to the turnover intentions of state government employees. State and Local Government Review, 43(2), 110–122.

Campbell, J. W., & Im, T. (2016). PSM and turnover intention in public organizations: Does change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior play a role? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(4), 323–346.

Carsten, J. M., & Spector, P. E. (1987). Unemployment, job satisfaction, and employee turnover: A meta-analytic test of the Muchinsky model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(3), 374.

Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65.

Cho, Y. J., & Lewis, G. B. (2012). Turnover intention and turnover behavior: Implications for retaining federal employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(1), 4–23.

Choi, K. (2006). A structural relationship analysis of hotel employees’ turnover intention. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 11(4), 321–337.

Choi, S. (2013). Demographic diversity of managers and employee job satisfaction: Empirical analysis of the federal case. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 33(3), 275–298.

Clark, A. E. (1997). Job satisfaction and gender: Why are women so happy at work? Labour Economics, 4(4), 341–372.

Cohen, G., Blake, R. S., & Goodman, D. (2016). Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(3), 240–263.

Cronbach, L. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334.

Davis, R. S., & Stazyk, E. C. (2015). Developing and testing a new goal taxonomy: Accounting for the complexity of ambiguity and political support. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(3), 751–775.

DeCoster, J. (1998). Overview of Factor Analysis. Retrieved from http://www.stat-help.com/notes.html

Dess, G. G., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). Voluntary turnover, social capital, and organizational performance. Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 446–456.

Dirks, K. T., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2004). Trust in leaders: Existing research and emerging issues. Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches, 7, 21–40.

Egan, T. M. (2008). The relevance of organizational subculture for motivation to transfer learning. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(4), 299–322.

Ellickson, M. C., & Logsdon, K. (2001). Determinants of job satisfaction of municipal government employees. State and Local Government Review, 33(3), 173–184.

Emiroğlu, B. D., Akova, O., & Tanrıverdi, H. (2015). The relationship between turnover intention and demographic factors in hotel businesses: A study at five star hotels in Istanbul. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207, 385–397.

Farris, G. F. (1971). A predictive study of turnover. Personnel Psychology, 24(2), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1971.tb02479.x

Feeley, T. H. (2000). Testing a communication network model of employee turnover based on centrality. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 28(3), 262–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880009365574

Felps, W., Mitchell, T. R., Hekman, D. R., Lee, T. W., Holtom, B. C., & Harman, W. S. (2009). Turnover contagion: How coworkers’ job embeddedness and job search behaviors influence quitting. Academy of Management Journal, 52(3), 545–561.

Ferguson, E., & Cox, T. (1993). Exploratory factor analysis: A users’ guide. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 1(2), 84–94.

Fields, G. S. (1976). Labor force migration, unemployment and job turnover. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 58, 407–415.

Freeman, R. B., & Medoff, J. L. (1984). What do unions do. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 38, 244.

George, J., & Wallio, S. (2017). Organizational justice and millennial turnover in public accounting. Employee Relations, 39(1), 112–126.

Gillet, N., Gagné, M., Sauvagère, S., & Fouquereau, E. (2013). The role of supervisor autonomy support, organizational support, and autonomous and controlled motivation in predicting employees’ satisfaction and turnover intentions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(4), 450–460.

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488.

Guan, Y., Wen, Y., Chen, S. X., Liu, H., Si, W., Liu, Y., … Dong, Z. (2014). When do salary and job level predict career satisfaction and turnover intention among Chinese managers? The role of perceived organizational career management and career anchor. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(4), 596–607.

Hammer, T. H., & Avgar, A. (2017). The impact of unions on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover. In What do unions do? (pp. 346–372). Routledge.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Killham, E. A. (2003). Employee engagement, satisfaction, and business-unit-level outcomes: A meta-analysis. Gallup Organization.

Hausknecht, J. P., Trevor, C. O., & Howard, M. J. (2009). Unit-level voluntary turnover rates and customer service quality: Implications of group cohesiveness, newcomer concentration, and size. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 1068.

Hayton, J. C., Allen, D. G., & Scarpello, V. (2004). Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7(2), 191–205.

Hemdi, M. A., & Nasurdin, A. M. (2007). Investigating the influence of organizational justice on hotel employees’ organizational citizenship behavior intentions and turnover intentions. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 7(1), 1–23.

Holtom, B. C., Mitchell, T. R., Lee, T. W., & Eberly, M. B. (2008). 5 turnover and retention research: A glance at the past, a closer review of the present, and a venture into the future. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 231–274.

Hom, P. W., Lee, T. W., Shaw, J. D., & Hausknecht, J. P. (2017). One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 530.

Hsu, M. L., & Chen, F. H. (2017). The cross-level mediating effect of psychological capital on the organizational innovation climate–employee innovative behavior relationship. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 51(2), 128–139.

Irvine, D. M., & Evans, M. G. (1995). Job satisfaction and turnover among nurses: Integrating research findings across studies. Nursing Research, 44(4), 246–253.

Jabeen, F., & Isakovic, A. A. (2018). Examining the impact of organizational culture on trust and career satisfaction in the UAE public sector: A competing values perspective. Employee Relations, 40(6), 1036–1053.

Jones, J. R., & Harter, J. K. (2004). Race effects on the employee engagement-turnover intention relationship. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11(2), 78.

Karatepe, O. M., Kilic, H., & Isiksel, B. (2008). An examination of the selected antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict and family-work conflict in frontline service jobs. Services Marketing Quarterly, 29(4), 1–24.

Kim, S. (2012). The impact of human resource management on state government IT employee turnover intentions. Public Personnel Management, 41(2), 257–279.

Kim, E. H., Lee, E., & Choi, H. J. (2012). Mediation effect of organizational citizenship behavior between job embeddedness and turnover intention in hospital nurses. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 18(4), 394–401.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Barton, S. M. (2001). The impact of job satisfaction on turnover intent: A test of a structural measurement model using a national sample of workers. The Social Science Journal, 38(2), 233–250.

Lee, G., & Jimenez, B. S. (2011). Does performance management affect job turnover intention in the federal government? The American Review of Public Administration, 41(2), 168–184.

Lee, T. W., Hom, P. W., Eberly, M. B., Li, J., & Mitchell, T. R. (2017). On the next decade of research in voluntary employee turnover. Academy of Management Perspectives, 31(3), 201–221.

Lopes Morrison, R. (2005). Informal relationships in the workplace: Associations with job satisfaction, organisational commitment and turnover intentions. Massey University.

Mallick, E., Pradhan, R. K., Tewari, H. R., & Jena, L. K. (2014). Organizational citizenship behaviour, job performance and HR practices: A relational perspective. Management and Labour Studies, 39(4), 449–460.

Mancuso, S. V., Roberts, L., & White, G. P. (2010). Teacher retention in international schools: The key role of school leadership. Journal of Research in International Education, 9(3), 306–323.

Mansfield, E. R., & Helms, B. P. (1982). Detecting multicollinearity. The American Statistician, 36(3a), 158–160.

Medina, E. (2012). Job satisfaction and employee turnover intention: What does organizational culture have to do with it? Columbia university.

Merit System Protection Board (2016). Merit Principles Survey Data 2016 Methodology and Material. Retrieved from https://www.mspb.gov/foia/Data/MSPB_MPS2016_MethodologyMaterials.pdf

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Sun, Y., & Xu, L. (2013). What factors influence the organizational commitment of public sector employees in China? The role of extrinsic, intrinsic and social rewards. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(17), 3262–3280.

Miles, J. (2005). Tolerance and variance inflation factor. In B. S. Everitt, & D. Howell (Eds.), Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science (1st ed.). Wiley.

Mobley, W., Griffeth, R., Hand, H., & Meglino, B. (1979). Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 493–522. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://A1979JS26200004.

Mowday, R. T., & Sutton, R. I. (1993). Organizational behavior: Linking individuals and groups to organizational contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1), 195–229.

Moynihan, D. P., & Landuyt, N. (2008). Explaining turnover intention in state government: Examining the roles of gender, life cycle, and loyalty. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 28(2), 120–143.

Nittoli, J. M. (2003). The unsolved challenge of system reform: The condition of the frontline human services workforce. The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Nouri, H., & Parker, R. J. (2013). Career growth opportunities and employee turnover intentions in public accounting firms. The British Accounting Review, 45(2), 138–148.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

Odland, G., & Ruzicka, M. (2009). An investigation into teacher turnover in international schools. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(1), 5–29.

Park, T. Y., & Shaw, J. D. (2013). Turnover rates and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 268.

Peters, L. H., Jackofsky, E. F., & Salter, J. R. (1981). Predicting turnover: A comparison of part-time and full‐time employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 89–98.

Peters, P., Tijdens, K. G., & Wetzels, C. (2004). Employees’ opportunities, preferences, and practices in telecommuting adoption. Information & Management, 41(4), 469–482.

Pitts, D., Marvel, J., & Fernandez, S. (2011). So hard to say goodbye? Turnover intention among US federal employees. Public Administration Review, 71(5), 751–760.

Price, J. L. (1977). The study of turnover. Iowa State Press.

Price, J. L. (2001). Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. International Journal of Manpower, 22, 600–624.

Quarles, R. (1994). An examination of promotion opportunities and evaluation criteria as mechanisms for affecting internal auditor commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Managerial Issues, 6, 176–194.

Rubenstein, A. L., Eberly, M. B., Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (2018). Surveying the forest: A meta-analysis, moderator investigation, and future‐oriented discussion of the antecedents of voluntary employee turnover. Personnel Psychology, 71(1), 23–65.

Sabharwal, M. (2015). From glass ceiling to glass cliff: Women in senior executive service. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(2), 399–426.

Shanock, L. R., & Eisenberger, R. (2006). When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 689.

Sturman, M. C., & Trevor, C. O. (2001). The implications of linking the dynamic performance and turnover literatures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 684.

Tinti, J. A., Venelli-Costa, L., Vieira, A. M., & Cappellozza, A. (2017). The impact of human resources policies and practices on organizational citizenship behaviors. BBR Brazilian Business Review, 14, 636–653.

Tziner, A., & Birati, A. (1996). Assessing employee turnover costs: A revised approach. Human Resource Management Review, 6(2), 113–122.

Um, M. Y., & Harrison, D. F. (1998). Role stressors, burnout, mediators, and job satisfaction: A stress-strain-outcome model and an empirical test. Social Work Research, 22(2), 100–115.

van Hooft, E. A., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., & Basbug, G. (2021). Job search and employment success: A quantitative review and future research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(5), 674.

Weng, Q., McElroy, J. C., Morrow, P. C., & Liu, R. (2010). The relationship between career growth and organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 391–400.

Xue, Y. (2015). Racial and ethnic minority nurses’ job satisfaction in the US. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(1), 280–287.

Yeun, Y. R. (2014). Job stress, burnout, nursing organizational culture and turnover intention among nurses. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society, 15(8), 4981–4986.

Yong, A. G., & Pearce, S. (2013). A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 9(2), 79–94.

Young, S. (2015). Understanding substance abuse counselor turnover due to burnout: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(6), 675–686.

Yücel, İ. (2012). Examining the relationships among job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention: An empirical study. International Journal of Business and Management, 7, 20.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

I submit this manuscript solely to this journal and I follow the ethnical rules.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

I have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hur, Y. Assessing the Effects of Workplace Contextual Factors on Turnover Intention: Evidence from U.S. Federal Employees. Public Organiz Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-024-00784-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-024-00784-y