Abstract

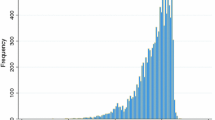

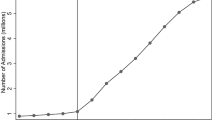

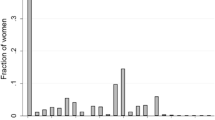

Rapid fertility decline has been witnessed in developing countries during the second half of the twentieth century. However, the consequences of fertility decline on average education and educational inequality at the societal level remain unexplored. Using data from the China General Social Survey (CGSS) and China Family Panel Survey (CFPS) (N = 44,918), this study contributes to the literature by answering two questions regarding the educational consequences of fertility decline in China with simulations. First, has the fertility decline improved human capital via declining average sibship size? Results reveal that the fertility decline during the 1950–1993 cohorts in China brought a 9% improvement in the average years of schooling compared to the Vietnamese counterfactual. Second, how does the differential fertility between groups contribute to educational inequality? Counterfactual simulations show that its impact on the educational disparity between males and females is limited. However, it has a marked impact on the rural–urban disparity in education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used are publicly available and can be accessed through the following approaches. The CGSS data can be accessed at http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/English/Home.htm. The CFPS data can accessed at http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/en/index.htm. The Vietnam Population Census data are provided by the General Statistical Office of Vietnam and accessed through IMPUS International.

Notes

Hukou refers to the household registration system in China under which everyone is assigned a hukou (household registration certificate) at birth. The hukou contains two-fold information. First, the category of one’s hukou status. The hukou status is divided into rural vs. urban or agricultural vs. non-agricultural. Second, the local administrative unit the hukou registered. The hukou must register to only one administrative unit at the lowest available level as one’s official/permanent residential place and under the supervision of all the higher levels of administrative authorities.

When using twin births as an instrument, the effects of sibship size are uncovered by estimating the effect of a twin birth at birth N on the outcomes of children born prior to this birth, conditional on families having at least N births. Since twins and singleton children are different in their birth endowment, like birth weight, and various other aspects that are related to future development, it is not appropriate to use births of twins as an instrument at N = 1, i.e., to compare twins with the single child at first birth, to estimate the effect of an increase in sibship size from 0 to 1. Similarly, the sex composition can only be used for families with at least two children to estimate the effect of the sibship size increase from 2 to more.

References

Angrist, J., Lavy, V., & Schlosser, A. (2010). Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Labor Economics, 28(4), 773–824.

Ashraf, Q. H., Weil, D. N., & Wilde, J. (2013). The effect of fertility reduction on economic growth. Population and Development Review, 39(1), 97–130.

Åslund, O., & Grönqvist, H. (2010). Family size and child outcomes: Is there really no trade-off? Labour Economics, 17(1), 130–139.

Bagger, J., Birchenall, J. A., Mansour, H., & Urzúa, S. (2013). Education, birth order, and family size (No. w19111). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Banister, J. (1987). China’s changing population. Stanford University Press.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), S279–S288.

Bian, Y., & Li, L. (2012). The Chinese general social survey (2003–8) sample designs and data evaluation. Chinese Sociological Review, 45(1), 70–97.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2005). The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(2), 669–700.

Bloom, D. E., & Williamson, J. G. (1998). Demographic transitions and economic miracles in emerging Asia. The World Bank Economic Review, 12(3), 419–455.

Bloom, D., Canning, D., & Sevilla, J. (2003). The demographic dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. Rand Corporation.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., Hu, L., Liu, Y., Majhal, A., & Yip, W. (2010). The contribution of population health and demographic change on economic growth in China and India. Journal of Comparative Economics, 38, 17–33.

Bongaarts, J. (2003). Completing the fertility transition in the developing world: The role of educational differences and fertility preferences. Population Studies, 57(3), 321–335.

Bongaarts, J. (2008). Fertility transitions in developing countries: Progress or stagnation? Studies in Family Planning, 39(2), 105–110.

Bongaarts, J., & Hodgson, D. (2022). Fertility transition in the developing world (p. 144). Springer.

Booth, A. L., & Kee, H. J. (2009). Birth order matters: The effect of family size and birth order on educational attainment. Journal of Population Economics, 22(2), 367–397.

Bound, J., Jaeger, D. A., & Baker, R. M. (1995). Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 443–450.

Cáceres-Delpiano, J. (2006). The impacts of family size on investment in child quality. Journal of Human Resources, 41(4), 738–754.

Cai, Y. (2008). An assessment of China’s fertility level using the variable-r method. Demography, 45(2), 271–281.

Chen, S. (2020). Parental investment after the birth of a sibling: The effect of family size in low-fertility China. Demography, 57(6), 2085–2111.

Choi, S., Taiji, R., Chen, M., & Monden, C. (2020). Cohort trends in the association between sibship size and educational attainment in 26 low-fertility countries. Demography, 57(3), 1035–1062.

Conley, D., & Glauber, R. (2006). Parental educational investment and children’s academic risk estimates of the impact of sibship size and birth order from exogenous variation in fertility. Journal of Human Resources, 41(4), 722–737.

Cuaresma, J. C., Lutz, W., & Sanderson, W. (2014). Is the demographic dividend an education dividend? Demography, 51(1), 299–315.

Das Gupta, M., & Mari Bhat, P. N. (1997). Fertility decline and increased manifestation of sex bias in India. Population Studies, 51(3), 307–315.

De La Croix, D., & Doepke, M. (2003). Inequality and growth: Why differential fertility matters. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1091–1113.

Den Boer, A., & Hudson, V. (2017). Patrilineality, son preference, and sex selection in South Korea and Vietnam. Population and Development Review, 43(1), 119–147.

Dribe, M., Oris, M., & Pozzi, L. (2014). Socioeconomic status and fertility before, during, and after the demographic transition: An introduction. Demographic Research, 31, 161–182.

Eastwood, R., & Lipton, M. (1999). The impact of changes in human fertility on poverty. The Journal of Development Studies, 36(1), 1–30.

Fang, C. (2018). Population dividend and economic growth in China, 1978–2018. China Economic Journal, 11(3), 243–258.

Fang, C., & Wang, D. (2005). China’s Demographic Transition: Implications for Growth. In R. Garnaut & L. Song (Eds.), The China Boom and Its Discontents. Asia Pacific Press.

Feeney, G., & Feng, W. (1993). Parity progression and birth intervals in China: The influence of policy in hastening fertility decline. Population and Development Review, 19(1), 61–101.

Feng, W., & Quanhe, Y. (1996). Age at marriage and the first birth interval: The emerging change in sexual behavior among young couples in China. Population and Development Review, 22(2), 299–320.

Goodkind, D. M. (2004). China’s missing children: The 2000 census underreporting surprise. Population Studies, 58(3), 281–295.

Goodkind, D. (2011). Child underreporting, fertility, and sex ratio imbalance in China. Demography, 48(1), 291–316.

Goodkind, D. (2017). The astonishing population averted by China’s birth restrictions: Estimates, nightmares, and reprogrammed ambitions. Demography, 54(4), 1375–1400.

Greenhalgh, S. (1989). Fertility trends in China: approaching the 1990s (Vol. 8). Population Council, Research Division.

Gu, J. (2022). Fertility, human capital, and income: The effects of China’s one-child policy. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 26(4), 979–1020.

Gu, B., Feng, W., Zhigang, G., & Erli, Z. (2007). China’s local and national fertility policies at the end of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review, 33(1), 129–147.

Guo, G., & VanWey, L. K. (1999). Sibship size and intellectual development: Is the relationship causal? American Sociological Review, 64(2), 169–187.

de Haan, Monique (2005) Birth Order, Family Size and Educational Attainment, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, No. 05–116/3, Tinbergen Institute, Amsterdam and Rotterdam

Hannum, E. (2002). Educational stratification by ethnicity in China: Enrollment and attainment in the early reform years. Demography, 39(1), 95–117.

Hannum, E., & Xie, Y. (1994). Inequality in China: 1949–1985. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 13, 73–98.

Hannum, E., & Xie, Y. (1998). Ethnic stratification in Northwest China: Occupational differences between Han Chinese and national minorities in Xinjiang, 1982–1990. Demography, 35(3), 323–333.

Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 46(6), 1251–1271.

Hermalin, A. I., & Liu, X. (1990). Gauging the validity of responses to questions on family size preferences in China. Population and Development Review, 16(2), 337–354.

Hesketh, T., Lu, L., & Xing, Z. W. (2005). The effect of China’s one-child family policy after 25 years. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(11), 1171–1176.

Joshi, S., & Schultz, T. P. (2007). Family planning as an investment in development: Evaluation of a program’s consequences in Matlab (p. 951). Yale University Economic Growth Center Discussion Paper.

Junhong, C. (2001). Prenatal sex determination and sex-selective abortion in rural central China. Population and Development Review, 27(2), 259–281.

Karra, M., Canning, D., & Wilde, J. (2017). The effect of fertility decline on economic growth in Africa: A macrosimulation model. Population and Development Review, 43, 237–263.

Kuo, H. H. D., & Hauser, R. M. (1995). Trends in family effects on the education of black and white brothers. Sociology of Education, 68(2), 136–160.

Kwong, J. (2011). Education and identity: The marginalisation of migrant youths in Beijing. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(8), 871–883.

Lam, D. (1986). The dynamics of population growth, differential fertility, and inequality. The American Economic Review, 76(5), 1103–1116.

Lavely, W., & Freedman, R. (1990). The origins of the Chinese fertility decline. Demography, 27(3), 357–367.

Lee, M. H. (2012). The one-child policy and gender equality in education in China: Evidence from household data. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(1), 41–52.

Lee, R., Mason, A., & Miller, T. (2000). Life cycle saving and the demographic transition: The case of Taiwan. Population and Development Review, 26, 194–219.

Li, H., & Zhang, J. (2007). Do high birth rates hamper economic growth? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1), 110–117.

Li, B., & Zhang, H. (2017). Does population control lead to better child quality? Evidence from China’s one-child policy enforcement. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45(2), 246–260.

Li, H., Yi, J., & Zhang, J. (2011). Estimating the effect of the one-child policy on the sex ratio imbalance in China: Identification based on the difference-in-differences. Demography, 48(4), 1535–1557.

Li, J., Dow, W. H., & Rosero-Bixby, L. (2017). Education gains attributable to fertility decline: Patterns by gender, period, and country in Latin America and Asia. Demography, 54(4), 1353–1373.

Liang, Z., & Chen, Y. P. (2007). The educational consequences of migration for children in China. Social Science Research, 36(1), 28–47.

Liu, H. (2014). The quality–quantity trade-off: Evidence from the relaxation of China’s one-child policy. Journal of Population Economics, 27(2), 565–602.

Lu, Y., & Treiman, D. J. (2008). The effect of sibship size on educational attainment in China: Period variations. American Sociological Review, 73(5), 813–834.

Maralani, V. (2008). The changing relationship between family size and educational attainment over the course of socioeconomic development: Evidence from Indonesia. Demography, 45(3), 693–717.

Mare, R. D. (1997). Differential fertility, intergenerational educational mobility, and racial inequality. Social Science Research, 26(3), 263–291.

Mason, A., Lee, R., Abrigo, M., & Lee, S. H. (2017). Support ratios and demographic dividends: Estimates for the World. Technical Paper, 1.

McElroy, M., & Yang, D. T. (2000). Carrots and sticks: Fertility effects of China’s population policies. American Economic Review, 90(2), 389–392.

Merli, M. G., & Smith, H. I. (2002). Has the Chinese family planning policy been successful in changing fertility preferences? Demography, 39(3), 557–572.

Minnesota Population Center. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.3. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.3

Murphy, R., Tao, R., & Lu, X. (2011). Son preference in rural China: Patrilineal families and socioeconomic change. Population and Development Review, 37(4), 665–690.

Parish, W. L., & Willis, R. J. (1993). Daughters, education, and family budgets Taiwan experiences. Journal of Human Resources, 28(4), 863–898.

Ponczek, V., & Souza, A. P. (2012). New evidence of the causal effect of family size on child quality in a developing country. Journal of Human Resources, 47(1), 64–106.

Pong, S. L. (1997). Sibship size and educational attainment in Peninsular Malaysia: Do policies matter? Sociological Perspectives, 40(2), 227–242.

Preston, S. H. (1974). Differential fertility, unwanted fertility, and racial trends in occupational achievement. American Sociological Review, 39(4), 492–506.

Preston, S. H., & Campbell, C. (1993). Differential fertility and the distribution of traits: The case of IQ. American Journal of Sociology, 98(5), 997–1019.

Qian, N. (2009). Quantity-quality and the one child policy: The only-child disadvantage in school enrollment in rural China (No. w14973). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Retherford, R. D., Choe, M. K., Chen, J., Xiru, L., & Hongyan, C. (2005). How far has fertility in China really declined? Population and Development Review, 31(1), 57–84.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Zhang, J. (2009). Do population control policies induce more human capital investment? Twins, birth weight and China’s “one-child” policy. The Review of Economic Studies, 76(3), 1149–1174.

Sen, G., Surana, M., & Basant, R. (2023). To what extent does the fertility rate explain the education gap? Population Research and Policy Review, 42(3), 35.

Torche, F. (2010). Educational assortative mating and economic inequality: A comparative analysis of three Latin American countries. Demography, 47(2), 481–502.

Treiman, D. J. (2013). Trends in educational attainment in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 45(3), 3–25.

Tsui, M., & Rich, L. (2002). The only child and educational opportunity for girls in urban China. Gender & Society, 16(1), 74–92.

Vogl, T. S. (2016). Differential fertility, human capital, and development. The Review of Economic Studies, 83(1), 365–401.

Wang, F., & Mason, A. (2008). The Demographic Factor in China’s Transition”. In L. Brandt & T. G. Rawski (Eds.), China’s Great Economic Transformation. Cambridge University Press.

Warner, W. L., & Srole, L. (1945). The social systems of American ethnic groups. Yale University Press.

Wei, Z., & Hao, R. (2010). Demographic structure and economic growth: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 38(4), 472–491.

Westoff, C. F. (1954). Differential fertility in the United States: 1900 to 1952. American Sociological Review, 19(5), 549–561.

Whyte, M. K., & Gu, S. Z. (1987). Popular response to China’s fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 13(3), 471–493.

Wietzke, F. B. (2020). Poverty, inequality, and fertility: The contribution of demographic change to global poverty reduction. Population and Development Review, 46(1), 65–99.

Womack, B. (2009). Vietnam and China in an era of economic uncertainty. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 36(2), 1–15.

Wu, X., Ye, H., & He, G. G. (2012). Fertility decline and women’s empowerment in China. International Center for Research on Women Fertility & Empowerment Working Paper Series, 006–2012.

Wu, X., & Li, L. (2012). Family size and maternal health: Evidence from the One-Child policy in China. Journal of Population Economics, 25(4), 1341–1364.

Wu, X., & Treiman, D. J. (2004). The household registration system and social stratification in China: 1955–1996. Demography, 41(2), 363–384.

Wu, X., & Zhang, Z. (2010). Changes in educational inequality in China, 1990–2005: Evidence from the population census data. In E. Hannum, H. Park, & Y. G. Butler (Eds.), Globalization, changing demographics, and educational challenges in East Asia. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Wu, X., & Zhang, Z. (2015). Population migration and children’s school enrollments in China, 1990–2005. Social Science Research, 53, 177–190.

Xie, Y., & Lu, P. (2015). The sampling design of the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chinese Journal of Sociology, 1(4), 471–484.

Xu, H., & Xie, Y. (2015). The causal effects of rural-to-urban migration on children’s well-being in China. European Sociological Review, 31(4), 502–519.

Ye, H., & Wu, X. (2010). Fertility decline and educational gender inequality in China. International Sociological Association-Research Committee on Social Stratification and Mobility (ISA-RC28).

Yilong, Lu. "The Household Registration System-Control and Social Distinction (hu ji zhi du—kongzhiyu she hui cha bie)." (2003): 124–126.

Yount, K. M., Zureick-Brown, S., Halim, N., & LaVilla, K. (2014). Fertility decline, girls’ well-being, and gender gaps in children’s well-being in poor countries. Demography, 51(2), 535–561.

Zhang, J. (1990). Socioeconomic determinants of fertility in China. Journal of Population Economics, 3(2), 105–123.

Zhao, Z. (2015). Closing a sociodemographic chapter of Chinese history. Population and Development Review, 41(4), 681–686.

Zhu, X., Whalley, J., & Zhao, X. (2014). Intergenerational transfer, human capital and long-term growth in China under the one child policy. Economic Modelling, 40, 275–283.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Richard Breen, John Ermisch, Jan O.Jonsson, and Vida Maralani for their valuable comments and suggestions on the earlier draft of this paper. The author also thanks the journal editor and reviewers for constructive comments. The research is supported by the PhD scholarship from the Chinese Scholarship Council.

Funding

This work is supported by Chinese Scholarship Council, 201808060314,Hanzhi Hu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, H. The Consequences of Fertility Decline on Educational Attainment in China. Popul Res Policy Rev 42, 94 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09834-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09834-7