Abstract

We examine whether the requirements of analytical skills and physical strength in jobs held by immigrant women in five major European destinations (France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the UK) converge to those of jobs of native-born women in their first ten years in the destination country. To this aim, we combine data from the European Labour Force Survey (2005–2015) of immigrant women arriving in these five countries and information about skill requirements from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). At arrival, migrants in Spain and France use much less analytical skills, but for the period before the Great Recession, that gap closes relatively fast over time compared to other destinations, particularly in the low end of the skill distribution. Physical strength requirements of immigrant’s jobs increase over time and the gaps open in countries where immigrants depart from relatively more strength-intense jobs, while they close in Spain where immigrants use less strength than natives at arrival. Our estimates are also robust to selection into employment both at the average and across the skill distribution using recent techniques. Since the Labour Force Survey does not have information on wages, we use wage information from the European Union Structure of Earnings Survey to proxy average immigrant-native wage gaps implied by our estimated skill gaps by country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research on labor market performance of immigrants overwhelmingly focuses on male immigrants. Yet, about 45 percent of all OECD immigrants in the early 2010s were women (OECD, 2017). To contribute to the understanding of the labor market outcomes of immigrant women, we study the skills required in jobs immigrant women hold during the initial ten years after migration compared to those of similar native-born women. To this aim, we combine data from the European Labour Force Survey (2005–2015) of immigrant women arriving in five European countries (France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the UK) and information about skill requirements from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). We study how differences in skill requirements evolve both at the average and across the distribution of skills. We include robustness analyses that correct for selection into employment both at the average and across the skill distribution. Since EU-LFS does not include detailed individual income, we use average wage and skill requirements by country to proxy the nativity wage gaps implied by our estimates.

Our analysis contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it supplements important work that looks at employment rate differences between immigrant and native-born women (Amuedo-Dorantes, 2007; Khoudia and Platt, 2018; Lee et al., 2020) by focusing instead on differences in the analytical and strength skill requirements of jobs immigrants hold compared to natives’ and whether they converge over time. Second, the paper covers an interesting period, which includes the economic crisis of the late 2000s and the EU enlargement; and, finally, it uses recently developed techniques to address selection into employment at different points of the distribution in skills. Our results inform policymakers by pointing out immigrant women as a potentially underutilized resource and highlight the need to promote inclusive labor markets that enhance gender equity and social cohesion in OECD countries.

While there is a large literature looking at immigrant women’s performance from a demographic and sociological perspective, much of the economics immigration literature on assimilation has traditionally focused on immigrant men (De la Rica et al., 2015) with only an emerging international literature documenting the specific issues surrounding labor market outcomes of immigrant women (Adserà & Ferrer, 2014, Khoudja & Platt, 2018, and Carrasco Carpio et al., 2020). Yet, most of this research measures women’s labor market integration with participation rates and wages (Adserà & Chiswick, 2007, Giorgiadis and Manning, 2011; Nicodemo & Ramos, 2012; Blau, 2016 Neuman, 2018, Damm, & Åslund., 2017), while devoting less attention to the type of jobs immigrant women hold in their countries of destination.Footnote 1 Lack of a panel data that consistently collect job market information across immigrant women in Europe explains the limited number of studies in the area. Notable exceptions are recent papers by Fellini and Guetto (2019) and Lee et al. (2020), which look at occupational attainment in various OECD countries. These papers focus on employment rates and, at most, broad occupational categories (such as high-skilled/low-skilled jobs, or blue/white collar jobs), and do not address the problem of selection into employment. We focus instead on how occupational requirements in different skills (analytical and physical strength) change as migrants stay longer in a destination and how they compare to natives’ during their first ten years in the country. Since workers could use a similar set of skills in completely different occupations, moving across occupations does not necessarily imply a major change in their labor market situation if they are still using similar skills. Conversely, a greater requirement of a given set of skills in a new job may indicate (or not) some degree of convergence to native’s patterns of employment, and possibly socioeconomic mobility, even when remaining in the same broad occupational category.

Tracking skills required in jobs to understand labor market dynamics is relatively common in economics. Autor et al. (2003) pioneered the use of O*NET information, to document changes brought about by technological progress in the use of routine and non-routine skills in the workplace. Subsequent literature has leveraged additional information from the O*NET regarding other types of skills. We follow Imai et al (2019), and others and use Principal Component Analysis to construct a vector of fundamental skill measures that summarizes the requirements listed in ONET for each three-digit occupation. In particular, we construct indexes for analytical and physical strength skill requirements to follow the progress of immigrants as these can capture the challenges that differences in language and culture between origin and destination countries may pose to the transfer of human capital (Adserà & Ferrer, 2016; Imai et al., 2019; Peri & Sparber, 2009). These two measures could roughly capture two universes of jobs – career jobs and non-career or “dead-end” jobs even though there is not a 100% correspondence between skills and those characterizations. Note that these two broad categories are not orthogonal, although they do show a substantial degree of (negative) correlation. Most of the occupations in the upper tail of the analytical skill distribution (managers and professionals and some clerical jobs in finance involving heavy numerical and computational tasks) are also at the bottom percentile of the physical strength distribution and vice versa. In general, these two broad skills are associated with different wage ranges, with analytical skills being better paid than physical strength skills. Hence, we cautiously interpret positive entry gaps with migrants requiring more analytical skills than natives, and small (or negative) entry gaps in strength skills, as a sign of better job opportunities for migrants. Subsequently, increasing (diminishing) levels of analytical (physical strength) skills over time could suggest migrant’s job improvement.

We examine both differences at the mean level of skills, and at different points of the skill distribution using quantile regressions. The latter is an important exercise because immigrant-native-born differentials are likely to differ across the skills distribution depending on the ability of immigrants to access a similar range of occupations than natives at a given quantile of skills. Country specific human capital and institutional barriers could prevent qualified immigrants from accessing the same type of jobs as equivalent native born. At the top of the skill distribution, immigrants trying to work as professionals may face barriers imposed by licensing bodies. At the bottom, lack of adequate language skills to communicate with clients and co-workers may have similar effects. In both cases, discrimination could also restrict immigrant employment in either type of occupation. Looking at quantile regression offers a more comprehensive view about the range and importance of skill differentials.

A major challenge when analyzing women’s performance is to account for opportunity costs women face when participating in the labor market, which introduce concerns of sample selection. To address this issue, we use not only standard Heckman procedures, (Heckman, 1976) but also recently developed econometrics procedures based on Arellano & Bonhomme (2017), which allow to recover coefficients at the mean and a quantile that are corrected for selection bias.

We find significant differences between skill requirements of immigrants’ job at arrival and those of similar native-born women, as well as in how these gaps evolve across countries during the first ten years in the country, even after accounting for selection into paid employment. Analytical skills gaps are generally negative and large, while strength gaps are positive or non-significant in most countries, except for Spain (where they are negative at arrival) and to a lesser extent Italy and Sweden. Entry gaps also differ by cohort of arrival within countries over the period of analysis in ways consistent with how the contemporaneous business cycle may have altered the incentives to migrate—particularly given the meager opportunities in many destination countries during the aftermath of the recent Great Recession. Immigrants to all countries (except the UK) show increases in the analytical skill content of their jobs over the first ten years spent in the country. This increase in analytical skills is faster in Spain and Italy, where negative gaps at arrival are larger. However, the physical strength content of immigrant’s jobs increases with years since migration. The gap opens up in all countries in which immigrants already perform more (or similar) strength-intensive jobs since arrival and closes toward convergence in Spain where immigrants work in less strength demanding jobs at arrival (especially among the most recent arrival cohorts). Convergence in skills does not take place within the ten-year window analyzed in our data. We provide a basic simulation of the wages differences between immigrants and natives implied by our estimated skill gaps across time, relying on average wages taken from the European Union Structure of Earnings Survey (SES), since the European LFS does not include detailed individual income.

Sect. “Contextual and theoretical framework” discusses the contextual and theoretical framework of this analysis; Sect. “Data and Method” follows with a description of the data and method employed. Sect. “Results” presents estimates of job-skill gaps of immigrant women at entry and over time, relative to native-born women and their implied wage differences, as well as estimates across quantiles of both the analytical and strength distribution. The paper ends with some concluding comments.

Contextual and Theoretical Framework

The economic performance of the five destinations included in our empirical analysis fluctuated noticeably during our sample period. During the early 2000s, Europe experienced a strong economic bonanza and, in countries, such as Spain and to some extent Italy, a booming construction sector attracted both skilled and unskilled labor. The severe crisis of 2008 affected all European countries to a different degree. The crisis greatly shaped immigration inflows and outflows to Italy and Spain as it was particularly intense in sectors with high levels of immigrant employment (construction, tourism, and related trades) (Rodriguez-Planas, 2016). Among Latin Americans in Spain, it affected men particularly harshly, while the finances of many households fell on women shoulders (Bueno Vidal-Coso, 2019) who traditionally have high employment rates in the country (Amuedo Dorantes and Rica, 2007). The sectoral distribution of immigrants in the other three countries was more balanced.

During the period of analysis, immigration policy changes affected the incentives and the feasibility of migration differentially by destination and arrival cohort (see De la Rica et al., 2015, for a review). The most relevant change in the EU context relates to the access to the labor market of migrants arriving from Eastern Europe. In May 2004, Ireland, the UK, and Sweden opened their labor markets to new members. From 2006 to 2009, 8-member states, including the remaining destinations in our sample, (2006: Greece, Spain, Portugal, Finland, Italy, 2007: Netherlands, Luxembourg, 2008: France) opened their labor markets to EU-8 workers. In 2005, Spain regularized the status of many existing immigrants through a large amnesty program that increased their opportunities in the formal labor market away from informal positions such as housekeeping (Elias et al., 2018). Those regulatory changes impacted the location choice of migrants besides existing economic and social conditions across destinations. Similarly, after the Great Recession, some European countries tailored their policies to the economic situation.Footnote 2

We use the standard human capital theory applied to immigration as the main theoretical framework to interpret estimates of the gap (at arrival and in subsequent years) of the skill content of jobs performed by immigrant women relative to those of native born, even though we recognize that other factors such as cultural norms or discrimination might have affected those patterns. The human capital model applied to immigration predicts that immigrants experience a depreciation of the human capital that is specific to their country of origin, such as language fluency, knowledge of institutions, and established networks. Part of the economic assimilation process consists in acquiring these forms of specific human capital in the country of destination (see seminal papers by Chiswick, 1986 and Duleep and Regets, 1999). Empirical economic research, mostly based on samples of men, typically document worse labor market outcomes for immigrants than for equivalent natives upon arrival, followed by a process of “catching-up” during the first ten years after migration. Whether complete parity to native levels is ever achieved is a matter of much controversy (Chiswick, 1986, Borjas, 1985; Duleep & Regets, 1997). Moreover, subsequent work points to substantial heterogeneity in the process of “catching-up” across immigrant (See Bevelander and Nielsen (2001) for Sweden; Clark and Lindley (2005) for the UK; and Clarke et al., (2019) for a comparison between Canada, Australia and the US).

Specifically, for women, sociodemographic characteristics, such as the presence of children, which may constitute a barrier for employment in the absence of the support of the extended family, affect the magnitude of the initial gap. Education and language fluidity are also important determinants of observed differences as they affect the opportunity cost of employment and access to career jobs. Other characteristics, such as cultural background or Visa immigration category (whether women arrive as an economic migrant, a refugee or for family reunification), which is not available in our data are also major factors behind differential labor market engagement.

Working hypothesis: Based on the previous discussion of literature that examines the employment rate differences between immigrant and native-born women and on the fact that greater analytical skill requirements tend to signal a more career-oriented type of job, we put forward two hypotheses regarding whether the requirements of analytical skills and physical strength in jobs held by immigrant women are expected to converge to those of jobs of native-born women in their first ten years in the destination country.

H1

Beyond educational differences, we expect the jobs held by immigrant women to differ in skill requirements from those of native-born women. Their lack of local human capital will result in large and negative initial gaps in analytical skills requirements, as these skills are most associated with career-type jobs. Alternatively, we expect smaller and possibly positive gaps in strength skills at arrival, as strength-intensive jobs likely require less local human capital, may already employ a substantial share of immigrants and provide a point of entry into the labour market for newcomers. Through the acquisition of local human capital and on-the-job learning, we expect these differences to decrease over time.

H2

Differences in skill requirements between immigrants and natives likely vary across the distribution of skill demands as well. Analytical skill gaps may be smaller at the top, since analytical-intensive jobs require high levels of human capital and attract immigrants with reasonable amounts of local human capital. If specific regulations or discrimination restrict access to those with foreign degrees gaps may be larger at the top. Greater difficulty acquiring analytical skills can slow down convergence at the top.

Physical strength gaps should be smaller at the bottom, to the extent that these require low levels of general or local human capital and might increase at the top as activities requiring high levels of physical strength become more complex.

Data and Method

European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS)

We use yearly data from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), conducted by national statistical institutes and centrally processed by Eurostat to provide a harmonized dataset at the European level. The survey includes, among other things, quarterly information on employment status and characteristics of occupation for those employed, but not on income or earnings. We employ EU-LFS weights to make the sample representative of the labor force in each country.

For tractability and data availability of key explanatory variables, we select five countries from the EU15 (Italy, France, Spain, Sweden, and the UK). Our selected countries account for some of the largest shares of immigration in Europe (besides Germany): Spain for 11%, Italy 8% France 13% and the UK 10%.Footnote 3Footnote 4 Together our sample of countries accounts for more than half of all European migrants to EU15 in 2005 yielding sufficiently large samples for analysis.

Job-Required Skills (O*Net Data Base)

We combine demographic and labor market information from the EU-LFS with information on the skill required by jobs held by both immigrant and native salaried women. The nature of the work performed in a particular sector is a dimension along which immigrant and native-born workers are likely to differ. Considering broad measures of occupational categories—such as blue/white collar or managerial/non-managerial jobs—to analyze these differences may miss a substantial part of the heterogeneity within them but including too finely itemized occupations in the econometric specification is impractical. The O*Net provides a very detailed classification to construct different indices that capture variation in different requirements with a continuous measure across occupations. An extensive literature has already combined information from the O*Net with European data. D’Amuri, and Peri (2014) use the O*Net to construct an index of complexity and, like us, merge it with the occupations in the EU-LFS. Ortega and Polavieja (2012) construct indexes for manual and communication skills in each occupation using the O*Net and merge these with the European Social Survey. Anghel et al., (2014) and Amuedo and De la Rica (2011) merge the O*NET with Spanish Labour Force Survey data. The implicit assumption in all this work is that the task content of occupations in the US and in and European countries is similar in relation to the skill dimensions being measured. This seems to be the case across all European countries, including CEE countries (see for instance, Hardy et al. (2018), Cedefop (2013) or Handle (2012)).

The O*Net contains information on requirements of formal education, job training, as well as tasks and environmental conditions of the jobs encompassing 277 descriptors. Researchers often use Principal Component Analysis (PCA), a common statistical technique to reduce dimensionality while preserving as much of the occupational data variation as possible. Some work employs multivariate factor analysis to reduce this complex information into a small number of orthogonal skills, thereby imposing that skill requirements in jobs are uncorrelated, a highly implausible assumption. Ascertaining the appropriate number of factors and interpreting these factors as particular skills is also somewhat arbitrary. We use an alternative related approach, as in Imai et al. (2019) and references therein, that separates ex ante the O*Net variables at three-digit occupation level into groups of job characteristics that are associated with a common skill component. Then, we estimate the principal component of each group of variables separately for each country and use the first factor loadings that explain over 85% of the variance to build each index.Footnote 5 The resulting skill indices are easier to interpret than those derived by the more general principal component method. Moreover, this methodology drops the unrealistic assumption that the underlying skills are orthogonal.Footnote 6

In this paper, we use information from both the O*Net 14.0 and O*Net 19.0, released in years 2009 and 2014, respectively, to construct a low-dimensional vector of skill requirements at the detailed three-digit occupational category using PCA.Footnote 7 We focus on one index for cognitive skills (analytical) and one index for manual skills (physical strength) with mean zero and standard deviation one over the whole working population. The analytical index includes O*Net information about, for instance, the importance that analytical thinking, mathematics, or acquiring and applying information has for the occupation. The strength index includes information about the importance of performing physical activities, such as climbing, lifting, balancing, walking, stooping, or exerting significant strength has for the occupation. (See table A1 in the online appendix) This classification focuses on a general notion of manual and non-manual skills that seems relevant to analyze the performance of immigrant women. The indexes could be considered to roughly capture two types of jobs, those associated with career jobs, and those associated with non-career jobs. These two broad categories show a substantial degree of (negative) correlation, with most of the occupations in the upper tail of the analytical skill distribution (managers and professionals and some clerical jobs in finance involving heavy numerical and computational tasks) being also at the bottom 25th percentile of the physical strength distribution. Similarly, the most heavily represented occupations at the bottom 25th percentile of the analytical skill distribution (cleaning services, personal care, and housekeeping and restaurant services) are also at the top 75th percentile of the physical strength skill distribution.Footnote 8

In general, these skill indexes are associated with different wage ranges, with analytical skills being better paid than physical strength skills. Hence, we cautiously interpret large positive entry gaps in analytical skills between migrants and natives, and small (or negative) entry gaps in strength skills, as a sign of better job opportunities for migrants. Subsequently, improving (diminishing) levels of analytical (physical strength) skills over time could suggest migrant’s job improvement. Note that the indexes measure skills from the demand side of the market, i.e., the skills involved in performing each job, not the actual skills of the worker.

Wages and Salaries: European Union Structure of Earnings Survey (SES)

Unfortunately, the lack of good earnings measures in the EU-LFS precludes a more complete picture of labor market performance. Nevertheless, to provide some contextual meaning of our skill measures in terms of potential income and the value of skill changes with years in the country, we obtain data on average hourly wages by two- or three-digit occupation from the European Union Structure of Earnings Survey (SES) for the years 2006 and 2014 and merge this information into our LFS data. The SES provides accurate and harmonized data on earnings in EU Member States for policy-making and research purposes.

Empirical Specification

To assess the gap in skills of immigrant women over the first ten years in the country relative to similar native-born women separately for each destination country, we estimate

The dependent variable is the skill index (Si), either analytical or physical strength, associated to the job of individual i. The vector Xi contains individual characteristics such as age (20–29, 30–49, and 50–59), indicators for area of origin of immigrants as defined below, and indicators for education attained (primary, secondary, and tertiary), and \({\beta }_{1}\) is the vector of associated coefficients. The area of origin indicators in Xi partially net out immigrant heterogeneity related to cultural background, including the quality of the home country institutions, such as the availability and quality of immigrant education. These likely play an important role on economic assimilation, as the closer the country of origin is in terms of economic development, institutions and culture to the host country, the lower the expected depreciation of immigrant’s human capital upon arrival (Belot & Ederveen, 2012).

Our sample includes cross-sectional information from 2005 to 2015 on women living in these five European countries that report information on education, country of origin, year of arrival (if immigrants), labor force status, and occupation (if employed). We select women over 20, who are bound to have completed compulsory schooling, and below 60, to reduce confounding retirement choices. Further, among those in the labor force, we select paid employees, because of the inability of properly reporting an occupation for the self-employed, to match it with the skill index. (Appendix figure A.1 shows trends in the share of immigrant by country).

We measure the influence of timing of arrival on the level of job skills with indicators for arrival cohorts, \({C}_{a}\), where a = before 2005, 2005–07, 2008–11, 2012–14, and a continuous variable measuring the number of years since the individual has arrived for the first ten years (\({Ysm}_{i})\). We include a separate indicator for immigrants who arrived more than ten years ago (Ysm > 10), since no detailed information regarding year of arrival is available for them. In robustness analyses, we include a vector of controls, Fi, related to the nature of the job and the firm in which individual i works, such as firm size, tenure, part time, industry, and whether the worker was overqualified for the job, and \({\beta }_{5}\) is the vector of associated coefficients.Footnote 9

The EU-LFS only discloses information about year of arrival for the first ten years a migrant resides in the country, and collapses “older” immigrants into a category of “more than ten years since arrival.” In our analyses, we focus on the initial ten years immigrants spent in the host country, or recent immigrants, which are the ones for which human capital models predict a faster rate of assimilation into the labor market. To assess the labor market outcomes of immigrants in the host country using repeated cross-sectional data the literature combines two variables—arrival cohort, and years since migration—to disentangle the effects of heterogenous arrival groups from those of economic assimilation that happens over time in the destination (Borjas, 1985).Footnote 10 We group arrival years in four arrival cohorts that experienced different broad economic trends: those who arrived before 2005, those arriving between the EU expansion and before the Great Recession of 2008, those arriving during the recession between 2008 and 2011, and those arriving during the partial recovery between 2012 and 2014 (See Table 1).

In Italy, Spain, and Sweden, around 22 to 25 percent of all immigrants arrived between 2005 and 2015. In Italy and Spain, these arrivals occurred during the mid 2000s, but the flow stopped almost completely over the last 3 years of the sample, reflecting the depth of the economic crisis affecting these countries. In the UK, around 30 percent of immigrants arrived within the last ten years, whereas in France these immigrants constitute only 14 percent of the sample. As we discuss later, the cohort analysis is important since it reveals considerable heterogeneity among immigrants that varies substantially by country. Our models do not include years fixed effects, and therefore, our cohort-fixed effects are a mixture of the arrival cohort composition which varies across time and the effects of the country’s economic conditions for immigrants at the time of their arrival. Estimates with years fixed effects are almost identical and available from the authors upon request.Footnote 11

The rights of immigrant from different origins changed over the sample period, and this could have affected their process of integration into the labor market. To account for this, the vector X contains indicators for area of origin as follows: (1) countries within the European Union as of January 2004 (EU15); (2) countries that became a Union member between May 2004 and July 2013 (EU28), to isolate the effect of the EU enlargement during our sample period; (3) a non-member European country (Other Europe); (4) North Africa and Middle East; (4) Other Africa; (5) Asia; (6) South and Central America, or (7) North America and the Pacific. (Table A3 in the appendix shows the distribution of immigrants by area of origin at the beginning and end of the sample).

Levels of human capital provide a (rough) indication of the skills supplied (rather than demanded) by the workforce and are routinely used as determinants of labor market success. Despite potential obstacles regarding credential recognition or discrimination, higher levels of pre-existing human capital should help an immigrant to acquire local human capital and to integrate in the labor force of the host country. See Table A4, Panel A, in the appendix for the distribution of education of immigrants and native born and labor force status and industry (Panel B)).

Table 2 presents the mean and standard deviation of analytical and physical strength skills for immigrant and native-born women in each country. Native-born women consistently employ lower levels of both skills at their jobs than the average worker does, while immigrant women typically use more (less) physical strength (analytical) skills in their jobs than the average worker does. Immigrant women also use less analytical skills than native women do, with the largest differences observed in Spain and Italy and the smallest differences in the UK. Skills also evolve differently with years since migration across countries (see Appendix figure A.2). Immigrants to the U.K. and, to a certain extent, Spain hold jobs requiring higher analytical skills over time in the country, Italy and Sweden show a much flatter profile, and France a somewhat “inverted U” profile.

Results

Entry Gaps and the Evolution of Skill Requirements of Immigrants Relative to Natives

To highlight the heterogeneity implicit across different cohorts of immigrants, we start by presenting a very simple model in Table 3 in which we only include an indicator for immigrant status as well as controls for age, and education. The immigrant coefficient in Table 3 averages differences between immigrant and native-born women across cohorts independently of the years spent in the country, though adjusted by age and education. Table 3 estimates are consistent with the descriptive data presented in Table 2. Immigrants generally work in jobs requiring less analytical skills and more physical strength skills than the native born. These differences are particularly important in Spain and Italy and are the smallest in the UK.

To show the substantial heterogeneity masked by the immigrant indicator in Table 3, we estimate a model in Table 4 that controls for cohort of arrival in the country, years since migration, and area of origin. Table 4 includes two set of coefficients of interest, first, the coefficients for the indicators of arrival cohorts, which measure the entry gap of that cohort compared to natives, and, second, the coefficients of years since migration, which measure the speed and direction of the changes of the initial gap with years spent in the country—whether migrant’s use of a particular skill increases or decreases over time. For each country, we show two specifications: (I) basic and (II) with additional demand side controls (F). While many of these variables (F) are arguably endogenous, it is interesting to show how including them affects the estimates of immigrant skill coefficients.

Estimates for arrival cohorts in Panel A in Table 4 show the average amount of physical strength skills required from immigrant women at the time of arrival, relative to native-born women, by country of destination. The initial entry gap for immigrant women in Spain is substantial and negative across all cohorts arriving after 2004, between − 0.099 and − 0.295 standard deviations less strength skills requirement than native-born women in model I, whereas immigrants to Italy and Sweden show smaller, often non-significant and positive gaps for cohorts arriving after 2004. Controlling for demand side factors (types of jobs, tenure, over-qualification) in model II produces qualitatively similar estimates in Spain (i.e., gaps between − 0.065 and − 0.263) and Italy but significant negative gaps in Sweden. The gap at the time of arrival for cohorts after 2004 is positive for immigrants to France and to the UK meaning that they initially work, on average, at jobs requiring more strength skills than the average native born does as expected by H1. However, these differences become smaller or not significant once we control for demand side factors. The effect of the demand side controls on strength gaps at entry, when comparing models I and II, suggests that immigrants in Sweden, the UK and France likely have lower tenure, more temporary contracts and/or concentrate in industries requiring high levels of strength skills. The coefficient of the trend variable for the first ten years since migration is positive in all countries except for the UK where it is essentially zero in both specifications. In the case of Spain, the positive coefficient for years since migration is consistent with a reduction of the gap in strength requirements (towards convergence with natives) because recent cohorts start in jobs requiring less strength skills than natives. In Spain, each year spent in the country increases the level of strength skills required by migrants 0.018 to 0.026 standard deviations (depending on the specification) during the first ten years. However, when the relative skill gap of immigrant women is positive at arrival in the destination, as in France or Italy, the increases in the use of strength skills over time imply that immigrant women tend to perform even more physically demanding jobs than natives with time in the country and the gap widens. This later finding is not consistent with the expectation of convergence in H1.

Panel B in Table 4 reports similar estimates for analytical skills. Across arrival cohorts and countries, estimates generally indicate that the analytical skills required by the immigrants’ jobs at the time of entry are substantially lower than those of jobs held by similar native-born women, consistent with H1. Interestingly, in Spain and Italy, the entry skill gap is smaller for more recent arrival cohorts and is no longer statistically significant for the latest one that arrived 2012–14. In the UK, conversely, the entry skill gap increases for successive cohorts and it is substantial, − 0.325, for the 2012–14 arrival cohort. The coefficient of the trend during the first ten years since migration is positive and significant in all countries except for the UK. Thus, immigrants to Spain (and to a lower extent those in France, Sweden and Italy) increase the analytical skill content of their jobs (thereby reducing the skill gap), consistent with H1.

The inclusion of entry cohorts and assimilation trends allows us to unpack different stories for each country and each arrival cohort that are masked when we only consider one immigrant indicator. Nevertheless, the interpretation of these cross-country differences in entry gaps and their subsequent evolution requires caution. Over part of our sample period, European countries underwent a major economic recession with growing unemployment, particularly in Southern European countries. Absent panel data, whether the closing of the skill gaps between natives and immigrants in Spain is the result of true changes in the types of jobs immigrant women do or rather of changing composition of employment opportunities, differential dropping out of the labor force and rising unemployment in strength-intensive sectors remains to be assessed.

To better picture what these differences in skills imply in economic terms we use information from the SES on disaggregated occupations to obtain OLS estimates of the association between analytical skills (commonly positively associated with “better” jobs) and wages for the average worker across occupations. We obtain these estimates of the return to a skill using wages in both 2006 and 2014 separately and show them in Panel A in Table 5.Footnote 12 Then, in Panel B, we use these coefficients as a rough measure of the price of analytical skills to simulate the wage gap of different arrival cohorts both at entry and after 10 years since migration implied by the estimates from Table 4. For instance, the entry gap in analytical skills of immigrant women arriving in Spain between 2005 and 2007 (− 0.396) translates into €0.83 lower hourly wages (2.09 €/sd skill x (—0.396) sd skill) than those of the native born. After 10 year in Spain, the estimated skill gap has reduced to − 0.08 sd skil for immigrants in this arrival cohort (− 0.396 + 0.032*10 = − 0.08) implying a negative wage gap of €0.16. The largest hourly wage entry gap for this cohort corresponds to France, followed by that in Sweden, the U.K., Italy, and Spain. For the post 2007 cohorts, entry wage gaps in Spain and Italy substantially diminished, due to reduced skill gaps at entry relative to the native born. In Sweden and France, entry wage gaps decreased only slightly for subsequent cohorts as skill gaps did not change much. In the UK, the analytical skill gap of immigrants arriving between 2012 and 2014 was substantially larger (− 0.325 sd skill) and implies a large wage gap, €2.7 lower hourly wages than those of the native born.Footnote 13

For the cohort entering before the Great Recession in Spain and Italy, the simulated wage gaps shrank substantially after 10 years (from €0.83 and €0.90 lower wages at arrival to, respectively, only €0.16 and €0.36 lower hourly wages than comparable native born). The pattern is similar for France and Sweden, although the rates of convergence in analytical skill content to natives’ are somewhat slower and the initial gaps larger than in Southern Europe. In France the wage gap for the 2005–2007 cohort shrinks from €1.46 at arrival to €0.93 lower wages after 10 years, and in Sweden from €1.3 to €0.69 relative to natives in jobs with similar skill requirements. Finally, analytical skills (and wage gaps) do not significantly change in the UK with time spent in the country for these and subsequent cohorts. Wage gaps for cohorts arriving after the recession in Spain and Italy are projected to become positive after 10 years, suggesting rapid skill gains relative to the average native born. In France and Sweden wage gaps are projected to shrink by 60% for the latest cohort after 10 years in the country. Thinking of these differences relative to average wages in each country may provide a better sense of their “depth”. Entry gaps for the 2005–07 cohort constitute a larger fraction of the country’s average wage in Sweden and France (over 50%) followed by Spain and Italy (40% and 33%, respectively) and the UK (13%). For the most recent cohort, Spain and Italy show much smaller wage gaps relative to the average wage (10% or less) whereas entry gaps in the remaining countries hover between 33 and 41% of the national average wages.

As seen in the last three rows of Panel B in Table 5, valuating the skill gaps using 2014 wages does not change the qualitative nature of this exercise.

Our destination countries vary by institutional and historical factors that affect the participation of women in the labor market. This makes it important to account for selection into employment in our analysis of required job-skills. To assess the importance of differences in participation rates for our results, we estimate a Heckman regression model on a version of Eq. (1) that uses marital status and indicators for both presence of children and whether suitable dependent care is not available as sources of variation to determine wage employment. To the extent that these variables determine employment, the resulting estimates are free of selection bias (into wage-employment) and can be interpreted as those resulting from observing a random immigrant woman worker. Results from this estimation are in appendix table A.5. Importantly, these estimates are not qualitatively different from those in Table 4, although Heckman estimates of analytical skills at arrival indicate somewhat larger gaps than OLS estimates. In the case of strength skills, two distinctive patterns emerge. In Sweden and the UK, women who are more likely to be wage-employed are also more likely to hold jobs requiring higher levels of strength skill, where the opposite is true in Spain and Italy. Further, for Spain, Heckman estimates indicate substantially larger differences in physical strength in immigrant jobs than OLS estimates. The estimated coefficients for entry gaps in physical strength requirements either flip from negative to non-significant or imply large positive gaps, particularly for the most recent cohorts. According to these, a random immigrant woman entering Spain after 2004 would hold a job requiring more strength skills—rather than less—than the job of the average native-born worker.

Distribution of Required Skills: A Look at Quantiles

The observed gaps between skills required by jobs of immigrant and native-born women are likely not uniform across the distribution of each skill. How the gaps differ across this distribution may depend on the ability of immigrants to access a similar range of occupations than natives at a given quantile of skills. Access is likely defined by a combination of worker’s attributes (such as education), country-specific human capital and institutional barriers. Further, country-specific human capital and institutional barriers could prevent qualified immigrants to access the same type of jobs as equivalent native born.

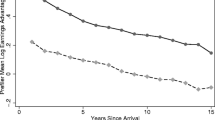

To analyze how the outcomes of immigrants may vary along the skill distribution, we estimate conditional (on cohort) quantile skill regressions at the 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 quantile of both analytical and physical strength skills. We display selected coefficients in Fig. 1 (Table A.6 in the appendix shows all estimated coefficients and standard errors). Figure 1A displays at the top estimates of the entry gaps in analytical skills, by country, for cohorts arriving right before the Great Depression (2005–2007) and at the bottom similar estimates for cohorts arriving between 2012 and 2014. For example, among those working at the 0.25 quantile of the skill distribution (i.e., personal care, cleaning, and restaurant services), immigrant women entering Spain between 2005 and 2007 worked in jobs that required 0.85 standard deviations less analytical skills than native-born women. On the other hand, among those working in jobs requiring high levels of analytical skills (i.e., managers, professionals, clerical jobs in finance) at the 0.75 quantile, immigrants in Spain typically use similar levels of skills than natives (only 0.1 standard deviations lower). Figure 1B displays similar estimates for strength skills.

Supporting H2, skill gaps are larger in jobs at the bottom quantile of the analytical skill distribution than at the top quantile, with some country differences. Spain, Italy and France show relatively large entry gaps between immigrants and native born at the lower end of the distribution, but only for cohorts entering during “boom” times (between 2005 and 2007) and not those who entered after the recession (2012–14). As later cohorts entered Southern European countries in the aftermath of the Great Recession when unemployment was high, particularly in low-skilled sectors, likely affected the selection of these new migrants. This may explain why differences at the bottom of the analytical distribution disappear in these countries for these cohorts. On the other hand, Sweden shows the largest differences in entry gaps between the upper and the lower parts of the analytical skill distribution for both cohorts. The entry gaps for UK immigrants at the bottom and middle of the distribution increase substantially for the cohort entering after the Great Recession. Neither in France nor in the UK, there is a change in analytical skills associated with time spent in the host country (see Appendix table A.6). For the other three countries, these changes are generally positive and large, both at the bottom or middle range of the distribution. Also, in support of H2, there is no analytical skill convergence to natives at the top quantile.

In Fig. 1B, differences between the immigrant-native gaps in physical strength skills at the bottom of the distribution are smaller than for analytical skills and often not significant, with the exception of France, also supporting H2. In Sweden, the 2005–07 cohort displays the largest positive skill gap at the top of the skill distribution, indicating that immigrant women working in jobs at the 0.75 quantile of the strength distribution performed tasks requiring substantially larger amounts of physical strength than native born in the same range of jobs. For the cohort entering after the 2008 recession, France shows the largest (positive) gaps across the distribution and most countries show moderate to large positive gaps at the top of the distribution. The change in strength skills associated with time in the host country is generally positive. In Spain and Italy, the change is homogeneous across the distribution, concentrated at the median and top quantile in France, and around the median in Sweden and the UK (see Appendix table A6).

These cross-country and cohort differences likely result from a variety of factors, including institutional and individual reactions to the crisis such as selectively dropping out of the labor force or into the underground economy, or immigrant selection changes of immigration flows post-crises.

Finally, to consider the effect of sample selection on the distribution of skills we use a recent STATA command [arhomme], developed by Biewen and Erhardt (2021) and based on Arellano & Bonhomme (2017). It allows to recover the coefficients of the overall population in a given rank by looking at the quantile observations of the observed population, and to obtain corrected estimates of the whole distribution of skills. The intuition of the procedure is similar to the Heckman two-step model: if high values of the rank outcome are associated with low values of the probability of selection, then selected observations tend to show lower outcomes than those that are not. Table A.7 in the appendix shows quantile estimates corrected for selection as well as a measure of concordance—the Spearman’s rank correlation, a function of the copula parameter rho—quantifying the (ordinary) correlation between the rank outcome and resistance towards selection. Negative (or positive) concordance measures positive (or negative) selection. A positive Spearman’s measure indicates that high values of the rank outcome are associated with high resistance towards selection; hence, selected individuals tend to have lower outcomes than the rest (negative selection).

Estimates are qualitatively similar to those in Appendix table A.6, but smaller in magnitude in Spain, Italy, Sweden, and the UK, where the largest gaps are observed at the bottom of the distribution. Gaps become smaller across all quantiles for later arrival cohorts in Spain and Italy, but not for Sweden and the UK. In France, the correction selected results are larger than OLS but remain qualitatively similar with the largest gaps observed around the median of the distribution in both cases.

Conclusion

We broaden our understanding of immigrant’s women integration in the European labor market by analyzing the skills required in the jobs they hold at arrival and whether they converge over time to those of natives. We use both EU_LFS and O*NET information to estimate the differences between the analytical and strength skills required in immigrant’s jobs compared to similar native-born women, both at the mean and across the distribution of skills. Further, we use average hourly wages by three-digit occupation from the European Union Structure of Earnings Survey (SES) to provide a rough estimate of what estimated gaps in skills imply in terms of income differences in each country both at arrival and after ten years.

Analytical skills required in migrants’ jobs are relatively low across all destinations compared to those of natives (consistent with H1). In Spain and France, and, to a lesser extent in Italy and Sweden, immigrants experience significant increases in the analytical requirements of their jobs with time in the country but do not fully converge to natives within ten years except in the case of recent cohorts arriving in Spain and Italy. Except in Spain, immigrants usually work in jobs requiring more physical strength than their native-born counterparts. We unveil differences across arrival cohorts within countries over the sample period that are consistent with likely changes in incentives to move depending on the business cycle at arrival—particularly given the meager opportunities in many destinations during the aftermath of the Great Recession. For instance, after the 2008 crisis, the analytical skill gap closes in Spain, Italy, and France, potentially as a result of changes in migrant selection within much smaller inflows, while it increases in Sweden and the UK, countries that were not as harshly hit by the crisis. The largest gaps in analytical skills happen in jobs at the bottom and mid-level of the distribution, while differences at the top of the distribution are small. Conversely, there is not a clear pattern for strength skills, with generally more muted differences, but still relatively large gaps both for France at the bottom and Sweden at the top.

Labor market choices of women in general, and particularly those of immigrant women are complex. To the extent that marital status and the presence of young children determine employment (as considered in the Heckman model), our estimates should not greatly suffer from selection (into employment) bias and can be roughly interpreted as those resulting from observing a random female worker. Selection issues might be less important among immigrant groups showing consistently high levels of participation across cohorts, such as those from Eastern Europe and South and Central America (see Amuedo and de la Rica, 2007). Our selection-corrected estimates (both for the average and across the distribution of skills), generally deliver similar qualitative results to OLS, albeit of different magnitude than the non-corrected estimates.

Lack of longitudinal data limit the study of the assimilation process of immigrants as it does not allow us to include individual fixed effects. In the absence of panel data with information on the individual work history, we are left to study the outcomes of immigrant cohorts observed at different points in time as a large share of the immigration literature does. Hence, by its very nature, cross-sectional cohort analysis can only capture average trends in the outcomes of immigrants arriving at a given time and cannot account for changes in cohort composition over time. Thus, we make no claim of causality, and our estimates should be interpreted in this context as descriptive outcomes of the average immigrant of a given entry cohort that is employed in different cross sections. Moreover, European countries underwent a major economic recession with growing unemployment during the last years of our sample, particularly in Southern European countries, which further complicates the interpretation of the data. Unfortunately, available data do not allow us to address whether the closing of the skill gaps between natives and immigrants in Spain or Italy is the result of true changes in the types of jobs immigrant women do or rather of changing composition of employment opportunities and rising unemployment in strength-intensive sectors. For instance, discouragement due to lack of occupational mobility leading to some women to drop of the labor force may bias results towards finding more skill convergence. One could use information on the type of VISA that immigrant women hold, which directly affects their ability to work and potentially the type of jobs women can access, to partially consider this channel, but this information is unfortunately absent from the EU-LFS.

Our results show that the gap in skill requirements and its evolution over time follows are heterogeneous across major immigrant recipient countries, even after accounting for selection into paid employment. Our estimates highlight the importance of host-country-specific factors and economic conditions at arrival in determining the path of skill convergence of immigrant women across European destinations. The overall picture is one of substantial convergence to the analytical skills of native-born jobs, even in times of recession. Full parity, however, is not reached within a ten-year window. With the lack of individual panel data, it is difficult to explore the mechanisms behind the rate of change in analytical skills. An exploration of whether the change in analytical skill requirements for immigrant women over time is due to formal education or training, on-the-job experience, or just the removal of institutional constraints (such as legalized immigrant status or affordable childcare) would be of great value to policymakers interested in promoting and encouraging an inclusive and diverse labor market that capitalizes on the abilities of immigrant women.

Data availability

Our research used as the main data source the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) data that is available for scientific purposes at EUROSTAT website: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/europeanunion-labour-force-survey. We also use data from Structure of Earnings Survey (SES) available for scientific purposes at EUROSTAT website: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/structure-of-earnings-survey. Finally, we use data from O*NET data files publicly available at O*NET Resource Center website: https://www.onetcenter.org/database.html

Notes

This is in contrast with other disciplines that have a long tradition of looking at occupational development. See for instance Ganzeboom et al.(1992)

In response to the crisis countries review their admission criteria (OECD 2009). Spain implemented a program assist repatriation of immigrants during economic downturns (including financial compensation) (Lopez-Sala and Ferrero-Turrion, 2009). The Czech Republic in 2009 put together a program to support unemployed migrant workers return home.

Regrettably, Germany, accounting for over 20% of all immigrant population in EU15 in 2005, does not report immigrant information in sufficient detail to be used in this analysis. Source: Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/migr_pop1ctz/default/table?lang=en.

Although Sweden’s share of total EU15 migration is not as large (2 percent), it is larger than that of other Nordic countries in the EU15, like Finland and Denmark providing sufficient sample size.

Factor loadings confirm that the variables chosen a priori are in fact adequate to capture the variance in the skill. See table A.2 for the factor loadings for each skill and country.

Bacolod and Blum (2010) used both methods to construct skills indexes and arrived to similar results in either case.

Our indexes are associated with the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), which underwent a substantial modification from ISCO-88 to ISCO-08, adopted in the EU-LFS in 2011. We use O*NET variables from both database releases and match using crosswalks constructed by the Institute for Structural Research (http://www.ibs.org.pl/resources). For details about how the index was constructed see Table A.1

The most significant departure from this general association are nurses and midwife professionals, whose jobs demand high levels of analytical skills and relatively high levels of physical strength skills, compared to occupations demanding similar levels of analytical skills.

See Arranz, et al. (2017)

Because of lack of detailed information after the tenth year, we do not include a quadratic function on years since migration. However, we consider in robustness analyses a spline function of the first ten years as well as the interaction of years since migration and group of origin. At any rate, our focus is on short-medium horizon.

. Excluding year fixed effects has the advantage of easing some of the computational demands in some of the robustness models included in the paper that control for selection bias of women in the labor market.

We use average wages at the beginning of the sample (2006) and at the end of the sample (2014) to test the robustness of the exercise to using wage data before or after the Great Recession when calculating the average price of skills. Figure A.3. in the appendix shows the correlation between both average strength (analytical) skills and average hourly wages in 2006, which are, negative (positive) but of different magnitude across countries.

Large fluctuations in the EURO/British pound exchange rate during this period leading to Brexit somewhat distort the absolute values of the implied wage differences in the UK.

References

Adserà, A., & Chiswick, B. (2007). Are there gender differences in immigrant labor market outcomes across European countries? Journal of Population Economics, 20(3), 495–526.

Adserà, A., & Ferrer, A. (2014). The myth of immigrant women as secondary workers: Evidence from Canada. American Economic Review, 104(5), 360–364.

Adserà, A., & Ferrer, A. (2016). Occupational skills and labour market progression of married immigrant women in Canada. Labour Economics, 39, 88–98.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & De La Rica, S. (2007). Labour market assimilation of recent immigrants in Spain. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2), 257–284.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & De La Rica, S. (2011). Complements or substitutes? Task specialization by gender and nativity in Spain. Labour Economics, 18(5), 697–707.

Anghel, B., De la Rica, S., & Lacuesta, A. (2014). The impact of the great recession on employment polarization in Spain. SERIEs, 5, 143–171.

Arellano, M., & Bonhomme, S. (2017). Quantile selection models with an application to understanding changes in wage inequality. Econometrica 85, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA14030.

Arranz, J. M., García-Serrano, C., & Hernanz, V. (2017). Employment quality: Are there differences by types of contract? Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1586-4

Autor, D., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. J. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Oxford University Press, 118(4), 1279–1333.

Bacolod, M. P., & Blum, B. S. (2010). Two sides of the same coin us “residual” inequality and the gender gap. Journal of Human Resources, 45(1), 197–242.

Belot, M., & Ederveen, S. (2012). Cultural and institutional barriers in migration between OECD countries. Journal of Population Economics, 25(3), 1077–1105.

Bevelander, P., & Nielsen, H. S. (2001). Declining employment success of immigrant males in Sweden: Observed or unobserved characteristics. Journal of Population Economics, 14(3), 455–72.

Biewen, M., & Erhardt, P. (2021). arhomme: An implementation of the Arellano and Bonhomme (2017) estimator for quantile regression with selection correction. The Stata Journal., 21(3), 602–625.

Blau, Francine D., 2016. "Gender, Inequality, and Wages," OUP Catalogue, Oxford University Press, number 9780198779971 edited by Gielen, Anne C. & Zimmermann, Klaus F.,

Borjas, G. (1985). Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. J. Labour Econ., 3(4), 463–489.

Bueno, X., & Vidal-Coso, E. (2019). Vulnerability of latin american migrant families headed by women in spain during the great recession: A couple-level analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 40, 111–138.

Carrasco Carpio, C., García-Serrano, C., & Hernanz, V. (2020). Work Trajectories of Female and Male Immigrants in Spain. International Migration, 58, 235–257.

CEDEFOP. "Quantifying Skill Needs in Europe. Occupational Skills Profiles: Methodology and Application." (2013).

Chiswick, B. (1986). Ìs the New Immigration Less Skilled Than the Old? Journal of Labor Economics, 4(2), 168–192.

Clark, K. and Lindley, J. (2005). ‘Immigrant Labour Market Assimilation and Arrival Effects: Evidence from the Labour Force Survey’. Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series, No. 2005004, University of Sheffield.

Clarke, A., Ferrer, A., & Skuterud, M. (2019). A Comparative Analysis of the Labour Market Performance of University-Educated Immigrants in Australia, Canada, and the United States. Journal of Labor Economics, 37(S2), S443–S490.

Damm, A. P. and O. Åslund. (2017). “Labour Market Integration in the Nordic Countries.” Nordic Economic Policy Review (Special Editors), Nordic Council of Ministers

D’Amuri, F., & Peri, G. (2014). Immigration, jobs and employment protection: Evidence from Europe before and during the Great Recession. Journal of the European Economic Association, 12(2), 432–464.

De la Rica, S., A. Glitz, and F. Ortega, (2015), Immigration in Europe: Trends, Policies, and Empirical Evidence, Editor(s): Barry R. Chiswick, Paul W. Miller, Handbook of the Economics of International Migration, North-Holland, Volume 1, 2015, Pages 1303-1362

Duleep, H., & Regets, M. (1997). The decline in immigrant entry earnings: Less transferable skills or lower ability? The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 37, 189–208.

Duleep, H. O., & Regets, M. C. (1999). Immigrants and human-capital investment. American Economic Review, 89(2), 186–191.

Elias, F., Monras, J., & Vazquez Grenno, J. (2018). Understanding the Effects of Granting Work Permits to Undocumented Immigrants. Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Fellini, I., & Guetto, R. (2019). A “U-shaped” pattern of immigrants’ occupational careers? A comparative analysis of Italy, Spain, and France. International Migration Review, 53(1), 26–58.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21, 1–56.

Georgiadis, A., & Manning, A. (2011). Change and continuity among minority communities in Britain. Journal of Population Economics, 24(2), 541–568.

Handel, M. (2012), “Trends in Job Skill Demands in OECD Countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 143, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k8zk8pcq6td-en

Hardy, W., Keister, R., & Lewandowski, P. (2018). Educational upgrading, structural change and the task composition of jobs in Europe. Economics of Transition, 26(2), 201–231.

Heckman, J. J. (1976). The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. In: Annals of economic and social measurement (vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 475–492). NBER.

Imai, S., Stacey, D., & Warman, C. (2019). From engineer to taxi driver? Language proficiency and the occupational skills of immigrants. Canadian Journal of Economics/revue Canadienne D’économique, 52, 914–953.

Khoudja, Y., & Platt, L. (2018). Labour market transitions among women from different origin countries in the UK. Social Science Research., 69, 1–18.

Lee, T., Peri, G. and Viarengo, M. (2020), “The Gender Aspect of Immigrants’ Assimilation in Europe”. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13922

López Sala, A. M., & Ferrero Turrión, R. (2009). Economic Crisis and Migration Policies in Spain. The Big Dilemma. Presented at the COMPAS conference.

Neuman, E. (2018). Source country culture and labor market assimilation of immigrant women in Sweden: Evidence from longitudinal data. Review of Economics of the Household, 16(3), 585–627.

Nicodemo, C., & Ramos, R. (2012). Wage differentials between native and immigrant women in Spain: Accounting for differences in support. International Journal of Manpower, 33(1), 118–136.

OECD. (2009). “International migration and the economic crisis: Understanding the links and shaping policy responses”, in International Migration Outlook 2009. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2017). International migration outlook 2017. OECD Publishing.

Ortega, F., & Polavieja, J. G. (2012). Labor-market exposure as a determinant of attitudes toward immigration. Labour Economics, 19(3), 298–311.

Peri, G., & Sparber, C. (2009). Task Specialization, Immigration, and Wages. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 135–169.

Rodríguez-Planas, N., & Nollenberger, N. (2016). Labor market integration of new immigrants in Spain. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 5, 1.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adserà, A., Ferrer, A.M. & Hernanz, V. Differences in Skill Requirements Between Jobs Held by Immigrant and Native Women Across Five European Destinations. Popul Res Policy Rev 42, 38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09784-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09784-0

Keywords

- Skill gaps

- European immigrant women

- Analytical skills

- Physical strength requirement

- Selection into employment

- Quintile distribution