Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the impact of demographic change on long-term, macro-level childcare and adult care transfers, accounting for the associated well-being effects of informal caregiving. We measure the impact of demographic change on non-monetary care exchanged between different groups by estimating matrices of time transfers by age and sex, and weighting the time flows by self-reported indicators of well-being, for activities related to childcare and adult care. The analysis employs cross-sectional data from the American Time Use Survey 2011–2013, and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Disability, and Use of Time Module 2013 to produce the estimates of well-being associated with the two forms of care and their future projections. Both men and women experience more positive feelings when caring for children than when caring for adults. As a whole, caregiving is an overwhelmingly more positive experience than it is negative across both genders and care types. Yet women often report more tiredness and stress than men when providing childcare, while also experiencing more pain while performing adult care, as compared to childcare activities. Women of reproductive ages spend double the amount of care time associated with negative feelings, relative to men, most of which is spent on early childcare. We project a progressively widening gender gap in terms of positive feelings related to care in the coming decades. Future reductions in absolute caregiver well-being influenced by demographic changes at the population level may reduce workforce participation, productivity, and adversely impact psycho-physical condition of caregivers, if not offset by targeted policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intergenerational transfers in the form of informal care—which can be seen as a major intangible resource—are a byproduct of systematic demographic changes, such as lower and later fertility, as well as reduced mortality and population aging. Changes in the population age structure determine the fraction of the population in each stage of the life course, predisposing some to provide and others to require care. However, the burden of care is not shared equally among caregivers and exposes some demographic groups to higher levels of physical, psychological, and economic stressors. Thus, the changing population composition has macro-level social and economic consequences surrounding the flow of resources as part of childcare and adult care arrangements. Recent work using microsimulation based on demographic processes and family/household structure analyzed future changes to caregiver supply and demand (Alburez-Gutierrez et al., 2021; Verdery & Margolis, 2017). These prior analyses establish the baseline for estimation, projection, and comparison of the national-level informal care patterns in view of the demographic structure and trends in the underlying populations. In addition, small-scale panel and interview studies have been previously conducted to evaluate individual caregiver financial and emotional well-being (Adams, 2006). Yet, national-level studies on the prospective evolution of well-being over time have been limited in scope. Moreover, caregivers often need to strike a balance between their financial and psycho-physical well-being, depending on their life course stage, cultural affinities, and commitments beyond caregiving, while spending various amounts of time and effort on unpaid care. Population dynamics naturally drive the changes in the availability of kin, household structure and exposures to generational care demands (Ice, 2022). Increasing longevity predisposes one to form tighter bonds with the family members, particularly when successive generations are less numerous than previous ones due to fertility decline. In this manner, dependence on strong multigenerational relationships might reduce the psychological burden of care on one hand, but on the other might increase the duration of exposure to care needs over time. Financial, psychological, and physical well-being of informal caregivers are thus mediated by the balance between the future exposure to care demands and multigenerational relations and support in the context of family care. However, when it comes to financial caregiver well-being, it is difficult to assign an exact dollar value to the direct and opportunity costs of interchangeable unpaid activities (Reinhard et al., 2019). In such cases, a minute spent on one activity is often considered to be indistinguishable from a minute spent on another. Although this assumption may be reasonable in a number of situations, the levels of well-being associated with performing specific informal care activities may vary substantially. All these considerations motivate the goal of the present study, which aims at assessing how demographic pressure shapes the well-being condition of informal caregivers at present and over time. In this paper we fill the gap in the literature by estimating the well-being associated with the amount of time transferred from caregivers to care recipients by age and sex. We then project the future evolution of well-being differentials by sex of caregivers, under the assumption that the relative index of well-being, measured from the time use modules of the American Time Use Survey and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, will persist.

Background

Informal family support, usually in the form of unpaid care, can be seen as an invisible backbone that affects the lives of a vast number of families with dependent and ailing members. The volume of informal support provided by family members is sparsely documented by conventional resource-flow measurement mechanisms (Gál et al., 2015). Due to the complexity and the physical and psychological pressures involved in providing informal care, individuals with family members who need frequent care partially substitute or outsource their care responsibilities, particularly if their relatives require long-term eldercare or have high levels of disability (Bonsang, 2009; Van Houtven & Norton, 2004).

The burden of care itself is not borne equally by all members of the caregiving community, and varies significantly by sex (Dukhovnov & Zagheni, 2015). Most studies on the determinants of the prevalence of household production have focused on the socio-cultural factors underlying the gender divide, family resources, or labor market conditions (Shire, Schnell & Noack, 2017). Yet, caregiver well-being is a crucial component in the process of deciding who will provide care, and in regulating the utilization of paid care services and informal care work (Kossek et al., 2001). Most studies on the prevalence of household production have focused on the socio-cultural factors underlying the gender divide, family resources, or labor market conditions, but not necessarily on psycho-physical well-being (Shire, Schnell & Noack, 2017). In fact, well-being differentials by caregiver gender and the type of care provided are quite pronounced. For instance, while physically demanding, providing childcare has been generally seen as fulfilling and meaningful in the long run because the caregivers are able to see their efforts come to fruition when the children succeed later in life (Hammersmith & Lin, 2019). McDonnell et al. (2019) find that although childcare is generally an overwhelmingly positive activity type, the differences by caregiver gender depend heavily on the physical context of the premises, specific activity with children, duration and time of day. Furthermore, notable differences exist both by parental and child gender. Mothers of only young daughters were shown to be more stressed and tired than mothers of only sons, whereas fathers’ well-being was not conditional on the gender composition of the children; otherwise, both mothers and fathers showed similarly high levels of happiness and meaning, regardless of gender of their children (Negraia et al., 2021). By contrast, providing adult care, particularly in the form of eldercare, usually has been regarded as much more challenging for caregivers. It has been shown that providing informal eldercare could lead to substantial work strain for caregivers, in part due to competing demands (Trukeschitz et al., 2012), and in part because it involves greater physical burdens than caring for children (de Oliveira et al., 2015). For instance, women, as mothers, are usually the primary caregivers for their own young children (Nomaguchi et al., 2005). But with the concurrent longevity increase, women have also been spending substantially more time on average caring for elderly parents, grandparents, or spouses (Wiemers & Bianchi, 2015). Studies on long-term caregivers for old-age adults project an increase in physical strain, detrimental to caregiver health (Capistrant, 2016). However, in view of the emerging trends in need-based old-age care, the evidence remains weak on whom will the burden of care for future old-age recipients fall (Ankuda & Levine, 2016; Stone, 2015).

Demographic changes in the recent decades have impacted the informal care scene by spawning a new stratum of caregivers. The increases in longevity, later marriages and delayed childbearing have gradually been giving rise to the so-called “sandwich generation” of adults with multiple simultaneous responsibilities, for young children and for their ailing parents (Agree, 2018). Microsimulation approaches to assess exposure to dual care responsibilities in the rich countries of Europe and North America project low prevalence of sandwiched care work in the coming decades as fertility, rather than longevity, is a primary factor behind generational sandwichness (Alburez-Gutierez, Mason, & Zagheni, 2021). In the US, fertility decline is thus projected to keep the percent of population that can be classified as sandwich generation in the general population low (Alburez-Gutierrez et al., 2021; Dukhovnov & Zagheni, 2015). In terms of the caregiver well-being, the physical and psycho-emotional challenges of care by a sandwiched caregiver are highly dependent on their particular situation. While it is true that sandwiched caregivers have a higher exposure-to-care potential than other caregivers, many studies miss the true extent of the caregiving load and burden on caregiver well-being, because sandwiched care is often not simultaneous on a day-to-day basis and may not be exclusively fulfilled by one caregiver, and thus varies in intensity with uneven temporal distribution of stressors (Boyczuk & Fletcher, 2016). Furthermore, socially and economically disadvantaged groups would face more acute individual load, especially as sandwiched caregivers, due to higher rates of poverty, single parenthood, poorer healthy life expectancy at older age and greater number of children on average (Treas & Marcum, 2011). On the flip side, extended kinship and social networks often fill the gap created by unfavorable socioeconomic dynamics, yet these coping mechanisms are not uniform on a macro scale (Agree, 2018). Cumulatively, individual decisions (e.g., postponed parenthood, opting to care for ailing parents, etc.) inevitably contribute to the population-level patterns of care and associated burden that morph alongside the demographic composition, tipping the balance between those who require care and those who can provide it at different stages in life. Recent trends in fertility postponement went hand-in-hand with the overall reduction of the number of children since the economic recession of 2008 (Hamilton, Martin & Osterman, 2020; Martin et al., 2018). This may temporarily enable increased prevalence of grandparental childcare, as grandparents who would otherwise be in their late 50 s or early 60 s and still be at work, now could find time to care for their young grandchildren in retirement (Sobotka, 2010). Similarly, with systematic declines in mortality among those over 65, as lethal conditions recently became manageable or treatable through medical intervention (Murphy et al., 2021), more older individuals have been living longer with mild-to-severe impairments that require long-term care (Perkins, 2021). In particular, the onset of cognitive conditions associated with increasing survival at older ages increases care burden on middle-age children as well as spouses, both of whom are typically female (Adams, 2006). Another important dynamic underlying the change in care arrangements for an average family is what could be ascribed to availability of kin (Hagestad, 1988). The continued declines in fertility gradually translate into fewer younger caregivers to take care of the growing cohorts of post-retirement Americans without close kin (Verdery & Campbell, 2019) or fewer family members who could share the burden of care (Margolis & Verdery, 2017; Stone, 2015). At present time, care provisions at old age among the Baby Boomer generation rely heavily on spousal care due to widely accepted generational marriage norms, as well as because of the availability of siblings (Agree & Glaser, 2009). The sibling pool has been on a gradual shrinking course over the recent decades and is likely to continue to decrease in the near future: as fertility declines for the generation of parents, this would translate into fewer available siblings, and with fewer own children to take care of the successive generations in later life (Agree & Glaser, 2009). Indeed, the kinship networks of the majority of Americans are projected to shrink in the coming decades (Verdery & Margolis, 2017). However, reductions in family size caused by declines in fertility are not necessarily indicative of deteriorating well-being, as caregiving trends in the past decades have remained relatively stable, in part because of improvement in health over time, and thus a reduction in the average individual’s need for care at older age (Janus & Doty, 2018). Furthermore, as mid-life divorces become progressively more common, the availability of married spouses at older ages may become more limited than in prior generations. On the contrary, re-marriages, non-marital unions and cohabitations are becoming increasingly common, especially in more egalitarian settings (Pessin, 2018), such that partners may still be available to provide care, both own childcare and old-age partner care (Noël-Miller, 2011). Moreover, ethnic and racial informal care differentials in the USA further demonstrated diverging trends in care prevalence, timing, and intensity, driven by cultural affinities, living arrangements, and norms, in terms of providing and receiving care (Cook & Cohen, 2018; Dukhovnov & Zagheni, 2019). Proximal cultural and familial composition factors play an integral role in both the availability of care as well as well-being of caregivers, as some ethnic groups that rely on filial piety, communal values and support have greater care support (Mendez-Luck et al., 2016; Powers & Whitlatch, 2016). For instance, due to the multigenerational household structure, earlier marriages and childbearing, and more children relative to non-Hispanic White families, Black and Latina women are often facing higher exposures to care demand in their early adulthood, whereas White women and men of any race bear heavier caregiving burden in later life (Ice, 2022).

From a population-level resource allocation standpoint, the demands for transfers of non-tangible resources (e.g., care) between various population groups have been steadily increasing (Ankuda & Levine, 2016). However, unlike monetary and material exchanges, including those tied to formal labor contracts, transfers of non-monetary support have been difficult to track and to include in economic calculations with consistency, despite recent instrument proposals (Hoefman et al., 2013). Due to increasing longevity and shrinking individual assets to contract formal care services in retirement, some of the proposed solutions to reduce dependency on the formal care sector included enabling the elderly to age in place (Miller et al., 2020). Yet, implementation of such initiatives requires extensive understanding of the preferences, needs, as well as the current underlying balance and elasticity of formal and informal care utilization. As a result, the character or quality of informal caregiver experience on a national scale remains an understudied component.

The economic logic and ethics of distribution of financial resources among dependent groups and their reallocation under the pressure of population aging has been a subject of scientific inquiry for a long time (Preston, 1984). It may be expected that continued declines in fertility and increases in longevity will increase the dependency of the population on eldercare services, financed by private and public monetary transfers that are already facing challenges (Lee & Mason, 2017). It is yet unclear how substantially caregiver well-being ought to factor in the current and future policy decisions for broad population groups. In order to accurately project the exact dependency balance, modeling is needed that accounts for a multitude of differentiating factors, such as socioeconomic background, social support networks, and the well-being of caregivers engaged in informal intergenerational transfers. For many countries, the formal side of this support mechanism has been investigated relatively well by the National Transfer Accounts (NTA) project, and by the UN System of National Accounts (SNA) (Lee & Mason, 2011). Our present contribution consists of documenting and projecting the amount and character of the informal care time transferred in the USA, with weights that introduce a qualitative component reflecting the caregivers’ physical and emotional well-being. To this end, we formulated the two interdependent research questions:

-

1.

The condition of the elderly deteriorates with age, as opposed to that of growing children. Likewise, as people find themselves in various life course stages, their commitment to providing care changes with age. In light of these patterns, what well-being differentials exist for male and female caregivers of various ages during the care activities?

-

2.

The well-being of informal caregivers can impact the decisions of individuals to provide care and thus the cumulative share of unpaid care in the national care supply, tipping the balance of formal and informal care markets for the dependent groups. As the population progressively ages, what effect would the future changes in the population structure bring about in terms of the aggregate unpaid caregiver well-being? What may this entail for the character of the future population-level informal care supply?

To answer these questions, we first describe our data and the approach to estimate matrices of care time transfers by age and sex, while incorporating a composite measure of caregiver well-being. We then present our results and demonstrate the projected shift in informal care dependency, driven by compositional changes in the population. In the final section, we conclude with a discussion of our results, and make recommendations for future research in the area of family and intergenerational economy.

Data

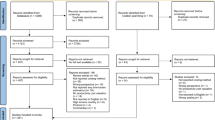

Our analysis is based on data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). Specifically, we use data from the ATUS (2011–2013) to produce matrices of transfers of care time, by age and sex. The ATUS, which is the most authoritative study of how people spend their time in the US, features a representative sample of about 12000 participants selected annually from the Current Population Survey (CPS) respondents. The data provide a detailed, chronological account of the respondents’ activities over a randomly selected day, including information about the other people who were present during the activities, and the duration and the location of the activities. In addition to data from the main questionnaire, we used data from the Well-Being Module for years 2012–2013. The module measures the emotional and physical impact of participation in a range of activities, the duration and the circumstances of which were assessed in the main questionnaire. Unlike the main ATUS questionnaire, the Well-Being Module consists of sets of exactly three randomly selected activities from the pool of eligible activities per respondent. The six psycho-physical feeling indicators measured across all activities and available in the Well-Being Module are happiness, meaning, pain, sadness, stress, and tiredness. Each of these indicators is on a seven-point Likert scale that ranges from zero to six, with zero representing the lowest intensity, and six representing the highest intensity. We pool the samples of the 2012 and 2013 Well-Being Module questionnaires to ensure that our sample size is adequate. However, ATUS carries an important limitation. The identification and classification of inter-household transfers of care time within activities by age and sex of care recipients is limited only to own non-household children and some elderly who receive informal care due to a health condition related to aging.

In order to address this limitation and to obtain more robust estimates for the entire cross-section of the population, we complement the ATUS data with data extracted from the PSID Disability and Use of Time supplement (DUST). PSID includes in its 2013 wave detailed 24 h time diaries of respondents aged 60 and older, along with those of their spouse or partner. The inclusion of PSID data into our analysis thus ensures that we have adequate sample size to draw conclusions about the non-household transfers to and by older adults. Moreover, when combined with detailed disability measures linked to the main PSID questionnaire, the DUST data can provide greater insights into the factors that promote subjective well-being among older adults experiencing functional losses, and among the individuals providing them with assistance. The pool of respondents we study is limited to those who indicated that they have engaged in caregiving. We divide our sample into those who cared for children and those who cared for adults based on their answers to two binary questions: one that asked whether they were caring for a child, and a second that asked whether they were caring for an adult. We examined the respondents’ self-reported levels of happiness, calmness, frustration, worry, sadness, tiredness, and pain associated with providing childcare or adult care, all recorded on a 0–6 Likert scale. Our analysis focuses on 2012 and 2013 data as, for those years, we have both time use and well-being measures from the two most authoritative sources in the US (ATUS and PSID). Having both sources enables us to produce more robust assessments of informal care transfers and associated well-being.

Methods

Our analysis is structured into three consecutive components. First, we compute the matrices of informal care time transfers by age and sex. Second, we use well-being data from ATUS and PSID to compute indices and associated ratios of positive and negative time experienced during caregiving activities. We then apply these ratios to the matrices from the first step to generate average daily flows of positive and negative care time by age and sex, from caregivers to care recipients, at the national level. Third, we use population estimates from the United Nations World Population Prospects (United Nations, 2019) to scale the total volume of positive and negative time spent by caregivers and received by care recipients of different age-sex groups nationwide. We then compute Care Support Ratios (CSR) and project these into the future to evaluate the proportion of positive and negative care time available at the population level. The CSR trend thus indicates the extent to which the changing demographic composition might impact the population-level demand for informal care and the caregiver well-being associated with it. We expand on each of these steps in order.

Estimation of Matrices of Informal Care Transfers by Age and Sex Using ATUS Data

Matrices of intra-household flows of care time could be estimated directly from the time use diaries, as the respondents recorded the time they dedicated to various caregiving activities, as well as the unique identifiers of the household members who benefited from this time. On the other hand, inter-household transfers could not be estimated directly because records of the age and sex of the care recipients were lacking. Inter-household flows are instead obtained indirectly by combining the available information about the time the respondents dedicated to inter-household care activities, as reported in their diaries, with the frequencies of care recipients in various age and sex groups assigned to the caregivers in the ATUS Eldercare Roster. The matrices of intra- and inter-household time transfers are subsequently combined into a single tabulation of overall care time transfers.

To construct the matrices of time transfers, we incorporate information on childcare and adult care transfers using distinct approaches for intra-household and inter-household care time flows. We begin by linking the ATUS Activity File and Who File (users who download IPUMS ATUS activity-level data extract do not need to perform this step). The Who File contains information about the people present during each activity, which is necessary for us to be able to classify the flow of time spent in care activities by the age and sex of potential care recipients. The Activity File describes the details of each activity, of which duration and classification are the most important for our purposes. If multiple eligible recipients were present (for example, two children in a childcare activity), the time for the activity is split equally among them, as we assume they were equally exposed to care.

Having linked the data and computed the time for each household member, we construct the intra-household matrices by age and sex. We choose to aggregate the matrices by standard five-year age groups (0–4, 5–9, 10–14, and so on), as these are the most commonly used groupings for aggregate demographic data. In the matrices, each of which describes care time flows in one of the four transfer combinations by sex (Male-to-Male, Male-to-Female, Female-to-Male, Female-to-Female), the cells represent the average daily amount of time spent by caregivers of the corresponding sex and age category (on the rows) caring for care recipients of certain age groups (on the columns). In each sex-to-sex transfer combination represented by a matrix, the averages for every cell are generated according to the ATUS methodology as follows:

where \({\overline{T}}_{ij}\)is the mean amount of time spent caring by a respondent of age group i for care recipients of age group j in an activity that could be childcare, if j < 18, or adult care, if j ≥ 18. \({t}_{i}\) is then the raw number of minutes in each transfer instance, and Wi is the survey weight of the caregivers belonging to age group i. The activities are broadly classified by the first four digits of the six-digit ATUS activity code, 0301xx, 0302xx, 0303xx, and 0401xx, 0402xx, 0403xx for household and non-household childcare, and 0304xx, 0305xx, and 0404xx, 0405xx for household and non-household adult care; in addition, activity codes 039999 and 049999 are included as miscellaneous help to household and non-household members.

For the inter-household matrices, the approach is less straightforward and needs several modifications. The main ATUS dataset does not list the age and sex of non-household members, unless they are the respondents’ own children. Therefore, we made use of the Eldercare Roster File, which is similar to the Who File described earlier in that we could extract from it a detailed demographic information about non-household members who were eldercare recipients or who received care due to a condition brought about by aging. Thus, these individuals were typically over the age 50, and more than 90% of them lived outside of the respondents’ households. This information is instrumental, since most inter-household adult care transfers occurred in this age category. As for children under 18 who were not the caregivers’ own children and were living outside of caregiver households, we assume that the average amount of daily care time these children received was similar to that received by their own non-household children. It is a weak assumption that does not entail deviations or bias of a large magnitude, as inter-household childcare provided to non-own children is fairly rare. Finally, for non-elderly adults, such as non-co-resident neighbors or friends, we split the time equally across all age/sex groups of inter-household care recipients aged 18–49. Additionally, to refine the estimates for middle-age inter-household adult care, we assumed that any member who is identified as a non-co-resident spouse belonged to the same age group as the caregiver, but is of the opposite sex.

Assembling all the components together and adding the numerators of the intra- and inter-household matrices before dividing by the corresponding caregiver weights (Eq. 1) results in the overall informal care time transfers matrices. We employ age-sex entries of these matrices as multipliers to calculate the projected amount of positive and negative time spent providing care on the national level to corroborate our second research question. However, we first need to calculate the indices of positivity and negativity with regard to the caregiver well-being.

Indices of Positivity and Negativity Associated with Childcare and Adult Care

We combine the information on feelings in the ATUS and PSID data to calculate indices of positivity and negativity associated with activities related to childcare and adult care. We then weigh the transfer matrices using these indices. The primary purpose of the indices of positivity and negativity of well-being during care activities is standardization, comparability and dimensionality reduction across samples. In our case, we wish to make complementary use of the two sources of data on caregiver well-being (ATUS and PSID) with disparate indicators of well-being that could be classified into positive and negative emotional outcomes. Thus, we first group the well-being states in the ATUS and PSID data into positive and negative classes. For each subset of the data, we calculate sample means for every well-being state. For positive feelings (ATUS: happiness and meaningfulness; PSID: happiness and calmness), six is the most positive value. For negative feelings (ATUS: pain, sadness, stress, tiredness; PSID: frustration, worry, sadness, tiredness, pain), six is the extreme negative value. For negative states, the calculated difference between six and the reported score indicates a “lack of negativity.” At this stage each variable receives the same weight in the calculation of the means, since both samples have similar indicators in terms of their number and substance, and they all measure either the level of positivity or negativity of an associated emotion. By applying this procedure to all of the well-being states, whether negative or positive, we end up with a scale from zero to six, with zero indicating high negativity and six indicating high positivity. Next, we compute the average positivity across all of the well-being states in each dataset (six in ATUS and seven in PSID), and weigh those values by the sample size of each dataset (ATUS: N = 3225 for childcare, N = 526 for adult care; PSID: N = 264 for childcare, N = 243 for adult care, each split between two sexes) in order to reflect the differences in uncertainty with respect to the estimates from the two datasets. In our specific instance, both ATUS WB and PSID DUST modules measure psycho-physical states on a 7-point scale. We further standardize them by computing respective positivity and negativity index ratios by care activity within each sex, so that they sum up to unity. The indices for emotional states related to childcare and adult care based on the combined ATUS and PSID data are reported in Table 1.

Future Projections Using Age Profiles of Positive and Negative Time Transferred

In this section we discuss the formal mathematical framework for generating per-capita age schedules of positive and negative care time production (time spent by caregivers) and consumption (time received by care recipients). Average profiles of positive and negative time production and consumption by age are obtained from the matrices computed earlier, weighted by positive and negative indices. These per-capita profiles represent the marginal row sums of each matrix. In the context of a stable equilibrium, the profiles of care time production by age can be obtained or interpreted as the leading eigenvector of the matrix of fractions of time production for the receiving group. Here, we explain the intuition that informs this approach.

Consider a population with m age groups, indexed by i. Total time spent providing care (i.e., positive or negative production) for age group i, ti, is written as:

where zij is the time flow from group i to group j. The expression can be rewritten to represent the flows between groups as the fraction of total time production for the receiving group. Thus, if we let \({q}_{ij} = ({z}_{ij} / {t}_{j})\), the model is expressed as:

or, equivalently, as:

By letting Q be the m × m matrix containing all the coefficients qij, and T be the m × 1 vector containing all the transfer ti terms, the model is written in a more compact form as:

or, equivalently, as:

The solution of Eq. 6 states that T is the eigenvector of Q associated with the leading eigenvalue. In other words, per-capita profiles of care time spent (production) by age in steady state can be interpreted as the eigenvector of a matrix of the type of Q associated with the leading eigenvalue. This result is general and applies to various classes of production profiles.

We combine the intermediary components (time matrices and positivity/negativity indices) and the above theoretical approach to produce future projections of care supply, adjusted for caregiver well-being. Assuming the per-capita production of each age group remains time-invariant, to evaluate the potential changes in terms of the amount and character of time transferred on the population level, as it is impacted by population aging, we combine our estimates of time transfers, weighted by the index of positivity and negativity, with age-specific population projections available in World Population Prospects for the years 2010–2100 (United Nations, 2019). The main notion behind our projections is the assumption that the evolving demographic structure of the population is the driving force behind the changes in outcome, given certain population attributes. It is likely that the rates of care supply by various groups of caregivers, and care demand by various groups of care recipients, as well as the levels of well-being associated with such transfers, may change over time. There is a large number of factors both compounding and countervailing which could impact the prevalence, intensity and well-being associated with care duties for individual caregivers. As an example, future health improvements and advances in health technology may translate in older adults no longer requiring as intense care or for as long a duration as they do today. On the other hand, fewer children in families over time may mean increased per-capita psycho-physical burden on adult child caregiver. Lacking any such information, we could then entertain a scenario in which the future per-capita rates of informal care consumption and production remain fixed at present levels. This approach has an inherent limitation of under- or overestimating the true burden of informal care in the future, the error in which would likely become more exacerbated the longer the projection horizon. However, we believe that in the short term (i.e., 10–20 years), this assumption is reasonable and enables us to offer a preview of the upcoming informal care landscape and the collective levels of caregiver well-being associated with it. The added value of this setup is that it is straightforward and adaptable for use in comparative studies. Specifically, it enables one to estimate the future care load and its burden with respect to caregiver well-being in different populations and countries, given the availability of rates of care supply by various groups of caregivers matching the future demographic profile of the population under study, broken down by age and sex.

In the first step to generate the projection, we first multiply all care time consumed by the 0–4, 5–9, and 10–14 age groups by the positivity/negativity ratios generated for childcare, and all other age groups by the ratios for adult care. Although individuals in the 15–19 age group are technically considered children, we treat them as adults for this specific procedure, since children in their late teens typically do not require the same level of attention from their parents as their younger counterparts. As a result, each matrix in the overall set is decomposed into a matrix representing flows of positive time and another representing flows of negative care time. The two sets of national average matrices were designed to sum up to the original matrix set of overall national average time transfers. As women and men engaged in care differentially, we compute their contributions in terms of time spent providing or receiving care separately before we add these values together to obtain the total care time for the entire population. The marginal sums of these decomposed matrices represent the mean daily age/sex profiles of positive and negative time spent by caregivers (time production) and time received by care recipients (time consumption) by age and sex. We weigh the matrices by the well-being of caregivers only, leaving the consumption side untouched, because the feelings used to generate the weights are reported only by the caregivers. We then adjust the production marginal sums of the matrices by a small factor to ensure the marginal total for production matches the marginal total for consumption (that is, the total time spent caring should equate the total time received). We note that caregiver subset matrices are not used in this exercise, because we have no data or knowledge of how many caregivers of particular age/sex groups will be providing care in the population in the future.

Secondly, we define the care support ratio (CSR) as a non-monetary alternative to the economic support ratio (SR) used by the National Transfer Accounts project community (Lee & Mason, 2011). This indicator measures the degree to which the supply of care matches the demand for care. In other words, a projection of CSR into the future demonstrates what would happen to the ratio between the total time produced by the caregivers and the time consumed by the care recipients, if people continue to behave like they did at the time of their survey interview on a per-capita basis. The only future change envisioned under this assumption is a demographic shift in which the population’s age structure would change according to the medium-fertility variant UN projections. A CSR for positive feelings reflects the fraction of care time during which caregivers experienced positive emotions, divided by the total care time consumed (i.e., the time received by care recipients). Similarly, a CSR for negative feelings indicates the fraction of care time during which caregivers experienced negative emotions, divided by the total time consumed. To calculate the CSR associated with positive and negative feelings, we keep the same denominator as in the traditional CSR, that is, the total amount of time received. The numerator is instead divided into two parts of positive time and negative time, which sums up to the total time spent by all caregivers.

Results

Several important features stand out in our estimates of overall flows of time spent caregiving by age and sex. First, as Fig. 1 shows, the majority of time was transferred from parents to young children: i.e., on average, for every minute spent providing care to a person aged 65 or older, around three minutes were spent providing care for children under age 15. These findings differ markedly by sex, as women spent about twice as much time caring for young children as men (Fig. 1c and d). Second, gender differences in transfers from grandparents to grandchildren are quite noticeable, as the grandfathers reported spending more time with their grandsons (Fig. 1a) and the grandmothers reported spending more time with their granddaughters (Fig. 1d).

Third, we observe a ridge along the main diagonal of the matrix of transfers for people of the opposite sex, indicating substantial transfers to spouses. In addition, we find evidence of sex differences in the time dedicated to caring for the elderly and care time needed by the elderly. For instance, elderly women appear to have slightly greater care needs than elderly men, which may be explained by women’s higher relative life expectancy and better health until much older ages. The analysis also shows that middle-aged women spent slightly more time caring for the elderly than middle-aged men. The panels in Fig. 2 complement these findings in that it contains the matrices of care time transfers by age and sex, but conditional on caregiving status. Old-age spousal care and grandparental childcare of up to 30 min per day on average stand prominently higher among those who provided care than in the general population (as in respective panels of Fig. 1), but with substantially larger values. Some old-age care for recipients aged 80 or above by retirement age adults is also indicative of informal commitment within less common care arrangements, such as between siblings and unrelated people.

Well-Being Associated with Childcare and Adult Care

In terms of evaluating average feelings of well-being, both women and men engaging in childcare reported high levels of positive emotions as informal caregivers. Women in the ATUS sample had average scores of 4.98 and 5.46, respectively, for happiness and meaning, whereas men manifested similar levels of happiness (5.03) and a somewhat lower sense of meaning (5.34) while caring for children. Female and male childcare providers had similar levels of positive emotions in the PSID sample, in terms of happiness (5.20 and 5.02, respectively) and calmness (5.40 and 5.47). The scores associated with adult care were markedly lower for caregivers of both sexes and in both samples, trailing the scores associated with childcare by an average of 0.77 and 0.54 scale points for happiness and meaning among women, and with the corresponding reduction for happiness and meaning of 0.57 and 0.58 for men in the ATUS sample. Reductions of mean positive feeling scores associated with adult care in the PSID sample, relative to childcare, were as follows: 0.65 lower on happiness and 0.36 lower on calmness among women, and 0.16 and -0.01 among men, respectively. Figure 3 shows the average well-being scores by gender and care type with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. In all positive emotion comparisons by caregiver gender the differences for childcare are insignificant in both samples.

Conversely, respondents reported lower levels of negative emotions associated with care in general, although the intensities of negative feelings were higher for adult care than for childcare. The overall feeling of sadness was low (under 1.0) and not significantly different across care types, both sexes, and both samples. Stress, worry and frustration were significantly higher for women who provided adult care, relative to women caring for children, but for men there was no practical difference between the two care types. The key differences for negative emotions linked to childcare and adult care were observed for tiredness and pain. Women caring for children in the ATUS sample (Fig. 3a) reported higher levels tiredness than for adult care (2.64 vs. 2.03), whereas female caregivers in PSID (Fig. 3b) rated childcare less tiring and painful than adult care (1.58 vs. 2.21). However, the same was true for men only in the PSID sample, reporting 0.66 higher tiredness during adult care than during childcare.

This difference between the two samples can be explained by the fact that respondents in the PSID sample were much older, with those providing childcare predominantly as grandparents, which tends to be less intense than parental care. On the other hand, more prevalent old-age spousal care aligns adult care providers of both genders across PSID and ATUS. Lastly, compared with childcare activities, the feelings of pain were noticeably less intense for adult care among ATUS male respondents than among PSID males (0.54 vs. 1.24). This is likely due to the fact that male caregivers in the ATUS sample were younger and did not provide much adult care on average, whereas old-age spousal care, coupled with physical aging likely played a role in this distinction. Ultimately, the caregivers of both sexes did not experience positive or negative feelings very differently for the same care types, with the only exception of women experiencing significantly higher tiredness and stress while performing childcare, relative to men in the ATUS sample (2.64 for women and 2.26 for men in terms of tiredness, and 1.5 and 1.12 respectively in terms of stress).

Next, we use the average scores for all the well-being states to compute composite indices of positivity and negativity. ATUS and PSID data are weighed according to their sample sizes by group and thus incorporated the differences discussed earlier. The indices and ratios of positive and negative emotions related to childcare and adult care are shown in Table 1. As expected, we find that childcare is a more emotionally positive activity than adult care, as illustrated with the comparison of mean indices and scaled ratios. Unlike differences in individual well-being states, the composite indicators clearly demonstrate average male caregiver advantage over female caregivers. This is not surprising, given that we found higher daily intensity of care among women in general, and in particular across ages of care recipients that were associated with higher induced negative feelings (i.e., adult and eldercare).

To produce a descriptive summary of our results thus far, we multiply the computed well-being ratios by the corresponding matrices of time transfers by age and sex (matrices in Fig. 1a and b are multiplied by male ratios, and Figs. 1c and 1d by female ratios, and the columns corresponding to the care recipients aged 0–14 years old by the respective childcare ratio, and the rest of the care recipient age groups by the adult care ratios), thus yielding the matrices of care time transfers weighted by positive and negative feelings. We carry out an equivalent procedure on the caregiver subset (Fig. 2a through d) for comparison. Per-capita profiles, shown in Fig. 4a and b, are the marginal row sums across a pair of national-level transfers matrices by caregiver sex (care time producers) and marginal sums of a pair of matrices by care recipient sex (care time consumers). Figures 4c and d represent an analogous set, but with respect to the average transfers in a caregiver subset (i.e., rather than the national average). It is important to emphasize that since care recipient well-being has not been measured, the age/sex profiles of well-being related to consumption ought to be interpreted as the average amount of emotionally/physically positive or negative time that caregivers of any age or sex spent while caring for care recipients of a particular age/sex.

From the broader picture, caregivers of both sexes provided at least double the care time of the national average. Relative to the national means, care providers of both sexes in the caregiver subset provided disproportionately more time at older ages, with about two-thirds as much time (≈2 h daily) in their pre-retirement and early retirement ages as in the childbearing ages devoted to what could be grandparental care. They spent an almost equivalent amount of time on old-age spousal care. Of course, not only women provided more time than men across all ages in both the national average and in the caregiver subset, a higher fraction of their care time was physically/emotionally negative, especially for women over the age 60 in the caregiver subset. From the perspective of where the care time is allocated, most of the negative feelings (such as pain and tiredness, as discussed earlier) were associated with caring for pre-teen children, much of which has been experienced by mothers. Remarkably, old-age care, though more intense among those who need to provide it, and typically associated with supporting an ailing spouse or a sibling, has not induced disproportionately high amount of negative time among caregivers. This finding is contrary to a common perception that most old-age informal adult care is physically or emotionally taxing. Our results show that such arrangement was certainly more intense and especially more prevalent in the caregiver subset, yet the time that could be characterized as negative represented up to a quarter of all time spent on care for care recipients of advanced ages.

Projections Using Age Profiles of Positive and Negative Time Transferred

Finally, we implement the intermediary components to produce future projections of care supply availability relative to its demand, adjusted for well-being. Figure 5 shows the estimated care support ratio (CSR) by caregiver sex, for which the indicators are designed so that the sum of the positive and negative CSR is equal to the total CSR. Assuming the per-capita production of each age group remains time-invariant in the future, this hypothetical scenario indicates that the overall care dependency will decline, prompted by increased supply of informal care, albeit not dramatically. The overall CSR for both sexes combined is projected to rise to a maximum of 1.06 in year 2030, after which it is projected to steadily decline back to parity (or 1.0) by the end of the century. However, population aging also implies that the gap between transfers associated with positive and negative feelings will shrink, as the CSR for positive feelings is expected to decline at a faster rate than the CSR for negative time transfers. The rate of shrinkage will be slow, in line with the projected rate of decline in fertility, diminishing the amount of early childcare transfers where much of the “negative” time is concentrated. In relative terms, panels in Fig. 5 demonstrate that male caregivers are cumulatively experiencing care demand burden with negative feelings about half the time as women are, all while taking up close to 60% of the care demand associated with positive feelings, as compared to women.

Note that production and consumption profiles are based on average daily rates. For example, at the national level, this means that an average American, regardless of caregiving status, experienced 6–10 min of negative time per day when caring for elderly people 85 years old or above. This could amount to up to 60 h per year. However, among those who actually provided care, this average number was substantially larger, with the emotional and physical outcomes of caregiving experience varying vastly between men and women. How much cumulative positive or negative care experience may be in the caregiver subset is unclear, as the future population of caregivers or care recipients is uncertain. If the fraction of the population who are caregivers remains the same as in 2011–2013 in the future, and the per-capita rates of care remain fixed, the quality of experience will be determined by the receiving end of care, namely care demands and recipient composition. The scenarios that we presented highlight some potential paths for the future. In the absence of additional and detailed information, they should be interpreted as potential trajectories conditional on given assumptions.

Discussion

In this paper, we generated matrices indicating who transfers time to whom by age and sex, and weighted time flows by self-reported indicators of well-being for activities related to childcare and adult care. With the empirical analysis, based on data from the American Time Use Survey and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics our findings are consistent with the existing literature that focuses on who spends time caring for others (Nomaguchi et al., 2005; Wiemers & Bianchi, 2015). Women are the primary informal caretakers for both children and the elderly in the vast majority of age groups. Conditional on providing any care, women’s engagement surpasses the average intensity of their male counterparts by nearly 30% of time per day (or approximately 40 min), at their peak during the reproductive age. In the general population women’s caregiving time exceeds that of men by 67% (or about 50 min per day). However, we show that much of this time is spent by women caring for children and old-age spouses. As our results illustrate, these are the groups of care recipients who are associated with the greatest per-capita amount of negative psycho-physical states among caregivers. Although positive feelings are experienced by both male and female caregivers nearly to the same degree, the negative feelings, most notably stress and tiredness are experienced significantly more acutely by women caring for children.

As one of the aims of this analysis, we assess the well-being differentials that exist for male and female caregivers of various ages during the care activities. Surprisingly, we find that caregivers experienced substantially more positive feelings when providing care, both for childcare and adult care. In comparison with adult care, childcare induced similar levels of sadness, but lower pain, tiredness and stress/frustration among women, but not among men. This pattern is reflected in the difference in per-capita positivity associated with providing childcare and adult care, where women beginning with reproductive ages and into the early retirement generated twice the amount of care time during which they experienced negative feelings, compared to men. Older women who often fill the roles of both spousal and grandparental childcare providers also experience lower levels of calmness when performing adult care, relative to men. Owing to the longer healthy lifespan older women’s exposure to care needs of others is more extended than for men. As compared to older generations of women at a particular advanced age, more recent cohorts of older women are more likely to still remain in a role of caregivers due to improved longevity and health. Nevertheless, the findings of our analysis on gender differences in caregiver well-being for men and women engaging in childcare are consistent with the prior research. A recent study on the topic further suggests that while male childcare providers are nominally happier and less stressed than females overall, this distinction is made more relevant when controlling for multiple contextual aspects, such as time of day, location, activity type, and its duration (McDonnell et al., 2019). We also find a disproportional burden that women bear in generating care time in older ages. Our findings are also in line with the results of the prior research that also demonstrated the disproportionate per-capita care time production occurring among non-White and immigrant women (Jessup et al., 2015). Cultural norms and availability of kin are undoubtedly playing a role in defining these patterns, but these nuances cannot be effectively captured by large-scale survey instruments such as in ATUS or PSID (Dukhovnov & Zagheni, 2019).

At the same time, the increase in the prevalence of negative instances associated with informal care activities, such as tiredness and stress would not likely preclude caregivers from engaging in care. However, the reduction of positive instances may disincentivize caregivers from performing these activities themselves. If the median age of a family were to increase, situations when working-age adults might choose not to devote additional time to playing with a child in lieu of caring for a disabled parent or relative might become more commonplace. For example, expectation of future burden of spousal care has been shown to negatively impact potential caregiver willingness to provide care at old age, depending on the gravity of the health condition of spouses requiring care (Wells & Over, 1994). Alternatively, one could imagine how negative experience with care (e.g., tiredness) might dissuade grandparents from voluntarily providing additional grandparental childcare when children’s parents are capable of providing it themselves or outsourcing it. On the national level, such occasions will likely translate into partial substitution of informal care with formal care that will need to be planned for and supplied through formal market mechanisms. However, in many other cases, as with most early childcare or care that is otherwise not elective, a choice to care or not to care may not exist. Lack of financial resources (Cook & Cohen, 2018), low income and opportunity costs (Reinhard et al., 2019), advanced disability of care recipients (Adams, 2006; Ankuda & Levine, 2016), and absence of kin or an extended social network (Margolis & Verdery, 2017) are some of the constraining factors that often override caregiver preferences, regardless of the individual cost to their well-being.

When it comes to need for any form of assistance, it has been previously shown that adult men have been more likely to provide monetary support to their parents and less time to their children, compared to women, who are the primary informal caregivers to either own children, elderly parents, or both (Friedman et al., 2017). As a result, if need for care arises, on average, female caregivers are less likely to be in a position to outsource their responsibilities, both due to monetary constraints and/or cultural expectations, and thus are more likely to endure negative psychological or physical experiences by providing care (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006). Our findings of greater emotional burden among female caregivers of older adults and spouses/partners are consistent with evidence from prior research. The care needs are also dependent on whether older care recipients are able to afford care arrangements from the formal care market using their life savings or assistance from government programs, as opposed to relying on their adult children. However, as cultural norms morph and men’s involvement in household production grows, as opposed to labor market participation (Bianchi et al., 2012), we expect the burden to be more equally shared in the future. This would likely narrow the gender gap shown in our projections of negative feelings.

Of course, one cannot discount the fact that employment, education, and career advancement are often regarded as barriers to informal care. Full-time employment and caregiving were shown to be causally related, yet profoundly incongruent for millions of American caregivers, for whom adult care decisions being particularly difficult due to professional advancement and lack of supportive policy (Schulz, 2020). Hammersmith and Lin (2019) suggested that the negativity of well-being associated with adult care is more precarious often in part due to adverse workplace policies that prioritize younger and entry-level employees providing childcare over than older and advanced-career employees who need to take care of the elderly parents. Several solutions may be available to counteract the disproportionate and deleterious effects on well-being of a particular subset of caregivers, be they caring for children, adults, or both. First, gender parity policy should become an institutionalized norm, whereby both men and women could take parental or family leave without facing career repercussions. While cultural gender norms and expectations often prescribe women to be primary caregivers for children, adults, or both, more equitable gender work and family policy could ensure that the burden of informal care is split more evenly between men and women. In turn, we expect that the associated well-being would also become more evenly distributed. Second, our findings show that grandparental childcare could indeed serve as a relief valve for parents in the next couple of decades, as health improvement in older ages will prolong healthy grandparenthood, while fertility decline will decrease the per-capita load on grandparents (Margolis, 2016). In effect, this would create a peculiar form of a “demographic dividend,” where a large number of healthier grandparents could meaningfully contribute to childcare effort. This dynamic could be factored into new policies to provide additional incentives for younger grandparents to uptake childcare duties.

To answer our second question, namely about assessing the effect that future changes in the population structure may bring about in terms of aggregate unpaid caregiver well-being, the future cumulative informal experience shaped by changes in the demographic composition is going to become less emotionally positive, but not to the same extent more negative. This is partly due to the fact that the current surplus of informal care is projected to decline over the coming decades, driven by reductions in fertility bringing down the amount of time spent in childcare (Lee & Mason, 2011; Verdery & Margolis, 2017). In other words, a likely future scenario includes reductions in the time spent on a group of child recipients which caregivers find most emotionally rewarding and fulfilling. At the same time, as indicated by our measure of Care Support Ratio, we are likely to witness small and gradual reductions of the surplus care at the population level. A continuously aging population will mean that the proportion of transfers in the form of adult care will increase relative to the proportion of transfers in the form of childcare. In a similar vein, if engaging in adult care induces somewhat more negative feelings than engaging in childcare, as corroborated by prior studies (de Oliveira et al., 2015; Trukeschitz et al., 2012), we can expect that in the nearest decades the overall proportion of negative feelings will increase relative to the overall proportion of positive feelings, but not the absolute amount of negative time. While, for example, providing long-term intensive care for an elderly spouse with cognitive impairments can be very emotionally taxing (Kim et al., 2017), it is not clear that it will become a more prevalent practice among informal caregivers, especially in light of the health and longevity improvements among the elderly.

Our findings illustrate that under the currently dominant gender norms surrounding informal care and its associated well-being outcomes, and given the projected demographic change, the future care burden would remain in the realm of women. Prior studies have highlighted the importance of the changing gender norms toward a more egalitarian distribution of effort between men and women in household production (Ice, 2022; Wiemers & Bianchi, 2015). We acknowledge these long-term processes of social change. At the same time, this article focuses on the role of demographic change: here we isolate the net effect of demographic change, holding everything else constant. Other factors, like changes in labor force participation and the availability of disposable capital that could be deployed toward outsourcing of care will be critical (Lee & Mason, 2017), albeit more uncertain.

The projections of cumulative well-being associated with the changing balance of care surplus or deficit we presented here highlight an urgent need to devise macro-level responses to address the consequences of poor well-being among groups of caregivers. For example, it has been shown that poor spousal caregiver well-being at older ages, particularly in the form of tiredness, is linked to higher healthcare expenditures for the care recipient (Ankuda et al., 2017). We show that the decline of positive psycho-physical well-being among female informal caregivers leaves them experiencing negative states more frequently. Many of these women constitute a part of the sandwich generation of caregivers with multiple care responsibilities for their own parents and children. Monitoring the overall dynamic of negative feelings at the population level and for minority caregiver groups will become of increasing importance given the increases in lifespan, shrinking savings, and preferences of older adults to age in place at home, close to their kin (Miller et al., 2020). To more accurately assess the relative burden over time more research is needed to decompose the cumulative share of negative time spent providing care in the future among sandwiched caregivers, relative to the general population.

Our study comes with limitations. Bound by a limited data sample, our estimates are not geared to provide a closer picture of well-being for the informal caregivers belonging to ethno-racial minority groups or the sandwich generation. As continued demographic pressures expand the diversity of forms of non-market care arrangements, the future degree of caregiving burden will depend not only on the future exposure to care needs within the context of a morphing household structure (Ice, 2022), but also on the evolution of cultural and gendered norms, which at present favor non-immigrant men, particularly non-Hispanic Whites (Dukhovnov & Zagheni, 2019; Negraia et al., 2018). Considering prior evidence and the results of our present analysis, we would expect immigrant communities and ethno-racial groups that are culturally affine to informal care transfers to continue bearing greater care burden earlier in life, whether as part of the sandwich generation or not, relative to the native born and non-Hispanic White Americans. We glide over the issue of well-being among population groups with differing cultural and normative traditions with regard to informal care. Further research is needed to uncover how cultural aspects, such as gender norms, filial piety and communal living contribute to the current and future landscape of informal care supply on a national scale. Such research on caregiver burden and well-being differentials ought to focus on minority caregiver groups that are gaining presence. These groups include sandwiched caregivers, who experience greater exposure to care demands and greater intensities, leading to varying well-being outcomes, and thus may face more acute forms of negative consequences associated with their caregiving duties. Lastly, limited by the scope of the data in our calculations, we assume a static image of per-capita care profiles by age and sex. We recognize that this is bound to change as societal expectations, standards of living, technology, and health advances may all change the ways in which care is performed. It is therefore important for future research to examine the evolution in the daily prevalence and intensity of care, as well as its associated well-being indicators, in order to more accurately monitor future patterns and trends.

Conclusion

Our analysis improves our understanding of the size, psycho-physical character, and evolution of national informal care supply relative to demand over time, in the context of the foreseen demographic changes. We argue that caregiver well-being ought to be factored in prominently in policy making at a national level. Governments of rich countries have been acutely cognizant of the economic consequences of population aging, yet often focused primarily on per-capita economic output or consumption as primary indicators to enact policy (Diener & Seligman, 2004). The implications of population aging clearly extend beyond ensuring that there is adequate public funding in the form of medical care, financial support, paid services, or other material transfers for children and the elderly (Kohli, 1999). Our work emphasizes that age and gendered well-being differentials exist in tandem with the intensity and prevalence differentials among informal caregivers. If not tackled, these will grow wider in the future and may entail a variety of economic consequences, not limited to increased caregiver health and support costs.

References

Adams, K. B. (2006). The transition to caregiving: The experience of family members embarking on the dementia caregiving career. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 47(3–4), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v47n03_02

Agree, E M. (2018). Demography of aging and the family. Future directions for the demography of aging: Proceedings of a workshop. National Academies Press. Washington. DC

Agree, E. M., & Glaser, K. (2009). Demography of informal caregiving In International handbook of population aging. Springer.

Alburez-Gutierrez, D., Mason, C., & Zagheni, E. (2021). The “sandwich generation” revisited: Global demographic drivers of care time demands. Population and Development Review, 47(4), 997–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12436

Ankuda, C. K., & Levine, D. A. (2016). Trends in caregiving assistance for home-dwelling, functionally impaired older adults in the United States, 1998–2012. JAMA, 316(2), 218–220. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.6824

Ankuda, C. K., Maust, D. T., Kabeto, M. U., McCammon, R. J., Langa, K. M., & Levine, D. A. (2017). Association between spousal caregiver well-being and care recipient healthcare expenditures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(10), 2220–2226. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15039

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., & Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces, 91(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos120

Bonsang, E. (2009). Does informal care from children to their elderly parents substitute for formal care in Europe? Journal of Health Economics, 28(1), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.002

Boyczuk, A. M., & Fletcher, P. C. (2016). The ebbs and flows: Stresses of sandwich generation caregivers. Journal of Adult Development, 23(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-015-9221-6

Capistrant, B. D. (2016). Caregiving for older adults and the caregivers’ health: An epidemiologic review. Current Epidemiology Reports, 3(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-016-0064-x

Cook, S. K., & Cohen, S. A. (2018). Sociodemographic disparities in adult child informal caregiving intensity in the United States: Results from the new national study of caregiving. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 44(9), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20180808-05

de Oliveira, G. R., Neto, J. F., de Camargo, S. M., Lucchetti, A. L. G., Espinha, D. C. M., & Lucchetti, G. (2015). Caregiving across the lifespan: Comparing caregiver burden, mental health, and quality of life. Psychogeriatrics, 15(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12087

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x

Dukhovnov, D., & Zagheni, E. (2015). Who takes care of whom in the United States? time transfers by age and sex. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00044.x

Dukhovnov, D., & Zagheni, E. (2019). Transfers of informal care time in the United States. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 17, 163–197. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2019s163

Friedman, E. M., Park, S. S., & Wiemers, E. E. (2017). New estimates of the sandwich generation in the 2013 panel study of income dynamics. The Gerontologist, 57(2), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv080

Gál, R. I., Szabó, E., & Vargha, L. (2015). The age-profile of invisible transfers: The true size of asymmetry in inter-age reallocations. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 5, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2014.09.010

Hagestad, G. O. (1988). Demographic change and the life course: Some emerging trends in the family realm. Family Relations. https://doi.org/10.2307/584111

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., Osterman, M. J., Driscoll, A. K., & Rossen, L. M. (2021). Births: Provisional data for 2020 Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no 12. National Center for Health Statistics.

Hammersmith, A. M., & Lin, I. F. (2019). Evaluative and experienced well-being of caregivers of parents and caregivers of children. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw065

Hoefman, R. J., van Exel, J., & Brouwer, W. (2013). How to include informal care in economic evaluations. PharmacoEconomics, 31(12), 1105–1119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0104-z

Ice, E. (2022). Bringing family demography Back in: A life course approach to the gender gap in caregiving in the United States. Social Forces. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soac041

Janus, A. L., & Doty, P. (2018). Trends in informal care for disabled older Americans, 1982–2012. The Gerontologist, 58(5), 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx076

Jessup, N. M., Bakas, T., McLennon, S. M., & Weaver, M. T. (2015). Are there gender, racial or relationship differences in caregiver task difficulty, depressive symptoms and life changes among stroke family caregivers? Brain Injury, 29(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.947631

Kim, M. H., Dunkle, R. E., Lehning, A. J., Shen, H. W., Feld, S., & Perone, A. K. (2017). Caregiver stressors and depressive symptoms among older husbands and wives in the United States. Innovation in Aging. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.3098

Kohli, M. (1999). Private and public transfers between generations: Linking the family and the state. European Societies, 1(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.1999.10749926

Kossek, E. E., Colquitt, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2001). Caregiving decisions, well-being, and performance: The effects of place and provider as a function of dependent type and work-family climates. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069335

Lee, R. D., & Mason, A. (Eds.). (2011). Population aging and the generational economy: A Global Perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lee, R. D., & Mason, A. (2017). Cost of aging. Finance and Development, 54(1), 7.

Margolis, R. (2016). The changing demography of grandparenthood. The Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(3), 610–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12286

Margolis, R., & Verdery, A. M. (2017). Older adults without close kin in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72(4), 688–693. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx068

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J. K., Driscoll, A. K., & Drake, P. (2018). Births: Final data for 2017 (v. 67, no. 8). National Vital Statistics Reports. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/60432

McDonnell, C., Luke, N., & Short, S. E. (2019). Happy moms, happier dads: Gendered caregiving and parents’ affect. Journal of Family Issues, 40(17), 2553–2581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19860179

Mendez-Luck, C. A., John Geldhof, G., Anthony, K. P., Neil Steers, W., Mangione, C. M., & Hays, R. D. (2016). Orientation to the caregiver role among Latinas of Mexican origin. The Gerontologist, 56(6), e99–e108. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw087

Miller, J., Ward, C., Lee, C., D’Ambrosio, L., & Coughlin, J. (2020). Sharing is caring: The potential of the sharing economy to support aging in place. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 41(4), 407–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2018.1428575

Mohide, E. A., Torrance, G. W., Streiner, D. L., Pringle, D. M., & Gilbert, R. (1988). Measuring the wellbeing of family caregivers using the time trade-off technique. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 41(5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(88)90049-2

Murphy, S. L., Xu, J., Kochanek, K. D., Arias, E., & Tejada-Vera, B. (2021). Deaths : final data for 2018 (v. 69, no. 13). National Center for Health Statistics. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/100479

Negraia, D. V., Augustine, J. M., & Prickett, K. C. (2018). Gender disparities in parenting time across activities, child ages, and educational groups. Journal of Family Issues, 39(11), 3006–3028. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18770232

Negraia, D. V., Yavorsky, J. E., & Dukhovnov, D. (2021). Mothers’ and fathers’ well-being: Does the gender composition of children matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(3), 820–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12739

Noël-Miller, C. M. (2011). Partner caregiving in older cohabiting couples. Journals of Gerontology Series b: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(3), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr027

Nomaguchi, K. M., Milkie, M. A., & Bianchi, S. M. (2005). Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 756–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x05277524

Perkins, M. M. (2021). Trends in aging and long-term care In Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. Academic Press.

Pessin, L. (2018). Changing gender norms and marriage dynamics in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12444

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series b: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(1), P33–P45. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.P33

Powers, S. M., & Whitlatch, C. J. (2016). Measuring cultural justifications for caregiving in African American and white caregivers. Dementia, 15(4), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214532112

Preston, S. H. (1984). Children and the elderly: Divergent paths for America’s dependents. Demography, 21(4), 435–457. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060909

Reinhard, S. C., Feinberg, L. F., Houser, A., Choula, R., & Evans, M. (2019). Valuing the invaluable: 2019 update charting a path forward. AARP Public Policy Institute, 146, 1–32.

Schulz, R. (2020). The intersection of family caregiving and work: Labor force participation, productivity, and caregiver well-being in current and emerging trends in aging and work. Springer.

Shire, K. A., Schnell, R., & Noack, M. (2017). Determinants of outsourcing domestic labour in conservative welfare states: Resources and market dynamics in Germany (Duisburger Beiträge Zur Soziologischen Forschung No. 2017–04). Universität Duisburg-Essen, Institut für Soziologie. https://doi.org/10.6104/DBsF-2017-04

Sobotka, T. (2010). Shifting parenthood to advanced reproductive ages: Trends, causes and consequences A young generation under pressure? Springer.