Abstract

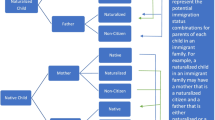

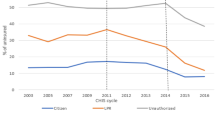

Using restricted data from the 2001–2014 California Health Interview Surveys, this research illuminates the role of legal status in health care among Mexican-origin children. The first objective is to provide a population-level overview of trends in health care access and utilization, along with the legal statuses of parents and children. The second objective is to examine the nature of associations between children’s health care and legal status over time. We identify specific status-based distinctions that matter and investigate how their importance is changing. Despite the continuing significance of child nativity for health care, the descriptive analysis shows that the proportion of Mexican-origin children who are foreign born is declining. This trend suggests a potentially greater role of parental legal status in children’s health care. Logistic regression analyses demonstrate that the importance of parental legal status varies with the health care indicator examined and the inclusion of child nativity in models. Moreover, variation in some aspects of children’s health care coalesced more around parents’ citizenship than documentation status in the past. With one exception, the salience of such distinctions has dissipated over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Andersen model draws attention to societal-, system-. and individual-level factors (Andersen and Newman 2005). Societal-level factors encompass technology, informal norms, and formal norms accompanied by sanctions for noncompliance with expectations for behavior. These operate through system and individual characteristics. System-level determinants encompass the amount and the organization of resources for service delivery (capital equipment, facilities, training, and labor). Individual-level determinants are predisposing demographic- (marital status), structural- (education), attitudinal-, and knowledge-related characteristics that affect propensities to use services. Individual enabling determinants are family resources (income) and community resources that a person has access to. Real and imagined health conditions are also individual determinants. Accordingly, legal status is a “predisposing structural characteristic” that also impacts “enabling determinants.” The following treatment is consistent with this model without being explicitly structured by it.

Until the 2009 Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act, federal funds could not be used to cover the undocumented and LPR’s with less than 5 years in the U.S. This act lifted the five-year ban, but California used state funds in prior years to cover permanent resident children who were recent migrants (Fortuny and Chaudry 2012). Medi-Cal and Healthy Families were limited to “lawfully present” children age 0–19 with family incomes below 250 % of the federal poverty level. As noted below, recently passed legislation will expand eligibility to the undocumented.

For example, income guidelines for a family of two parents and two children are $0–$33,465 for Medi-Cal and $33,466–$97,000 for Covered California. The tax for being uninsured is $700 per adult and $48 per child or 2.5 % of income, whichever is greater (California Health Benefit Exchange 2013). There is currently a proposal before the state legislature to fund participation in Covered California for the undocumented.

The 287(g) and Secure Communities programs sought to coordinate subfederal police agencies with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 287(g) was initiated in 1996 to extend federal enforcement authority to local police, but participation has not been widespread (www.ice.gov). From 2008 to 2014, Secure Communities focused on sharing information about persons detained by local agencies. However, 287(g) is winding down and Secure Communities has been replaced by the Priority Enforcement Program to target serious threats to public safety. An additional sign of greater receptivity is the 2014 California Trust Act which limits police authority to detain the undocumented for minor offenses. Recent legislation also permits the undocumented to get driver’s licenses and prohibits employers from threatening to contact federal agencies about persons protected under California labor laws (leginfo.legislature.ca.gov). Lastly, Los Angeles was the epicenter of a massive protest by 500,000 people in 2006 against federal legislation to control undocumented immigration by toughening penalties for migrants, their employers, and those who assist them.

The mother or father was the most knowledgeable adult for 97 % of children. Parent’s gender can only be investigated fully in recent surveys due to data limitations for prior years. Supplementary analyses indicate that it is not a significant predictor and does not affect other estimates.

The total N of cases accounts for almost all Mexican-origin children. A small number with deceased parents or parents who do not live in the United States are excluded (<1 %). The CHIS also imputes missing data. Therefore, there is no attrition due to incomplete information except for the exclusion of a trivial number of observations in the 2001 survey that lacked imputed values (.1 %).

Basing measurement on guidelines is complicated by changing recommendations. In 2001, the American Academy of Pediatrics advised once-a-year visits starting at 24 months. A 30-month examination is now recommended after the 24-month visit, followed by yearly checkups starting at 36 months. Physician contact for some children is limited to emergency rooms, but this is infrequent in the CHIS. Almost all children in the CHIS have a usual source of care and less than 1 % of parents identify emergency rooms as their child’s usual source of care.

Referring to those without a green card as “undocumented” is common despite the inclusion of a small number of visa holders who are authorized to temporarily reside in the United States (see Ortega et al. 2007; Vargas-Bustamante et al. 2012). Although we cannot identify the visa holders, some studies estimate that 93 % of all nonpermanent residents are undocumented (Gonzalez-Barrera et al. 2013). This figure is likely to be higher for Mexicans.

To our knowledge, utilizing data on both parents and treating them separately from children are unique. Another study focused on one parent and the child jointly without considering the full array of statuses and both parents (Stevens et al. 2010).

The specific counties are: Los Angeles, San Diego, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Santa Clara, Alameda, Sacramento, Fresno, Kern, Ventura, Tulare, and San Joaquin. Each has at least two percent of the 21,441 children. We expanded the individually identified counties to 26 in the preliminary analysis, but models failed to converge for the 2013–2014 survey. This reduction to 13 counties does not affect results for prior years.

The number and age distribution of migrant children reflect U.S.-bound migration and Mexico-bound return migration. Consistent with declining immigration, the foreign born are aging out of the 0–11 bracket. Interstate migration is a possible contributing factor, but we find no evidence in the ACS that nativity differences in movement into and out of California played a role. Also, vital statistics show that the share of Mexican-origin births to native-born mothers increased in California.

The 2001 CHIS was conducted during a brief downturn. The Great Recession occurred nationally from December, 2007 to June, 2009, but California got an early start with the collapse of housing and was slow to recover. Unemployment peaked at 12 % around the time of the 2009 CHIS (fielded September, 2009 to April, 2010). By the end of 2015, unemployment was at 5.8 % (data.bls.gov).

Tests for interactions using different model specifications were performed to determine whether associations are time invariant (with parent status, child nativity and year as categorical variables). For example, tests were conducted for a model restricted to a single measure of status, year and the year*status interaction terms. Similar tests were performed for a model with all covariates. The multiplicative terms for parent status*year do not improve the fit of any model, but child nativity*year always does so. Attention to the results for both variables by year is still warranted to avoid missing changes for a subset of time points that might be obscured by this procedure.

The 2013–2014 values for children with two permanent resident parents are 80 % in top panel (all children) and 91 % in bottom panel (U.S.-born children). This suggests that the anomaly in top panel is specific to foreign-born children, who were less likely to be insured in 2013–14 than in earlier years.

There are too few cases to examine the association with parental status by year for the foreign-born (N = 1220). For all years combined, this association is significant and revolves around citizenship (Wald χ2 = 21.4, p < .001). About 90 % of foreign-born children with two citizen parents, 76 % with one citizen parent, and 56–57 % with permanent resident or undocumented parents had insurance.

U.S.-born children predominate across all parent status groups, but their prevalence varies. For example, only 14 foreign-born children have two native-born parents. These children are excluded. Neither the odds ratios nor the standard errors are affected by this decision. For all years, over 80 % of those with two undocumented parents and at least 94 % in the remaining groups were native born. About 80 % of foreign-born children have two (65 %) or one undocumented (13 %) parent.

Estimates for children with two permanent resident parents in the first and last surveys are counterintuitive. In 2001 and 2011–2014, they were less likely than those with two undocumented parents to be insured in Model 1. Model 2 suggests that this reflects various background factors. Children of two permanent residents tend to be older than those with two undocumented parents. These children also have lower risks of living in poverty and being in a single-parent household. This intriguing finding is discussed further in the conclusion.

As for the covariates, poverty, family structure and year of survey affect insurance coverage (not shown). Overall, the odds for children in families with incomes at least 300 % of the federal poverty level are twice the odds for children in poverty (p < .001). Surprisingly, those who are “near” poverty (100–199 % of the threshold) are less likely than those below the threshold to be insured (OR = .77, p < .01). This is surprising because those below 200 % of the poverty line are eligible for public programs. Coverage is also less likely for children in single-parent families (OR = .85, p < .07) and for those observed during the first decade. In fact, the most recent years of observation are high points even after socioeconomic characteristics are accounted for.

Interaction terms for year*parental status are not significant using conventional criteria for the restricted models for either the total sample or the U.S.-born sample. This set of interaction terms does barely achieve significance for the model that includes all covariates for the full sample (p = .04) and is borderline significant for the native-born sample (p = .05). The results that are responsible for this are revealed below. All child nativity*year tests were not significant.

Seeing a physician is not associated with economic circumstances, family structure or year in multivariate models, but it is positively associated with education and negatively associated with the child’s age. In addition, having insurance is a strong predictor of physician visits.

Weaker associations would be expected from a reduction in statistical power and smaller group differences with the exclusion of the foreign born, particularly in early years.

References

Abrego, L. J. (2014). Latino immigrants’ diverse experiences of “illegality”. In C. Menjívar & D. Kanstroom (Eds.), Constructing immigrant “illegality” (pp. 139–160). New York: Cambridge Press.

Aday, L. A., & Andersen, R. (1974). A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research, 9(3), 208–220.

Andersen, R., & Newman, J. F. (2005). Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(4), 1–28.

Bachmeier, J. D., Van Hook, J., & Bean, F. D. (2014). Can we measure immigrants’ legal status? Lessons from two U.S. surveys. International Migration Review, 48(2), 538–566.

Baldassare, M. (2007). PPIC Statewide Survey: Californians & their Government. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California. http://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/survey/S_107MBS.pdf

Bean, F. D., Brown, S. K., Leach, M. A., Bachmaier, J. D., & Van Hook, J. (2013). Unauthorized Mexican migration and the socioeconomic integration of Mexican Americans. In J. R. Logan (Ed.), Diversity and disparities: America enters a new century (pp. 341–374). New York: Russell Sage.

Berk, M. L., & Schur, C. L. (2001). The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health, 3(3), 151–156.

Bosniak, L. (2006). The Citizen and the alien: Dilemmas of contemporary membership. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Broder, T. (2005). Immigrant eligibility for public benefits. In G. P. Adams (Ed.), Immigration and nationality law handbook 2005–06 (pp. 759–786). Washington, DC: American Immigration Lawyers Association.

California Employment Development Department. (2014). Economic trends affecting California’s long-term unemployed. In: California labor market trends. Issue Number 1. State of California. http://www.calmis.ca.gov/SpecialReports/CA-LMI-trends-Jan-2014-report.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2015.

California Health Benefit Exchange. (2013). Covered California: Report by the California Health Benefit Exchange to the Governor and Legislature. Sacramento: State of California.

California Health Interview Survey. (2014). Report 4: Response rates. CHIS 2011–2012 methodology report series. UCLA: Center for Health Policy Series.

Chavez, L. (2014). “Illegality” across generations: Public discourse and the children of undocumented immigrants. In C. Menjívar & D. Kanstroom (Eds.), Constructing immigrant “illegality” (pp. 84–110). New York: Cambridge University Press.

CONAPO. (2010). Migration & health: Mexican immigrant women in the U.S. México, D.F.: Consejo Nacional de Población.

Cousineau, M., Cheng, S., Tsai, K., & Diringer, J. (2012). California health care almanac. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation.

Coutin, S. B. (2011). The rights of non-citizens in the United States. Annual Review of Law & Social Science, 7, 289–308.

Department of Homeland Security. (2013). Yearbook of immigration statistics: 2013. Washington, DC: Office of Immigration Statistics.

Derose, K. P., Escarce, J. J., & Lurie, N. (2007). Immigrants and health care: Sources of vulnerability. Health Affairs, 26(5), 1258–1268.

Field Research Corporation. (2006). The Field Poll: February 12–26, #2185. http://field.com/fieldpollonline/subscribers/

Field Research Corporation. (2012). The Field Poll: September 6–18, #2430. http://field.com/fieldpollonline/subscribers/

Field Research Corporation. (2013). The Field Poll: February 5–17, #2439. http://field.com/fieldpollonline/subscribers/

Fix, M., & Zimmermann, W. (2001). All under one roof: Mixed-status families in an era of reform. The International Migration Review, 35, 397–419.

Fortuny, K. & Chaudry, A. (2012). Overview of immigrants’ eligibility for SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and CHIP. ASPE Issue Brief. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Gonzalez-Barrera, A., Lopez, M. H., Passel, J. S., & Taylor, P. (2013). The path not taken. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center. http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2013/02/Naturalizations_Jan_2013_FINAL.pdf Accessed February 11, 2015.

Groves, R. M. (2006). Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(5), 646–675.

Groves, R. M., & Peytcheva, E. (2008). The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(2), 167–189.

Hagan, J., Rodriguez, N., & Castro, B. (2011). Social effects of mass deportations by the United States government: 2000–2010. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(8), 1374–1391.

Hall, M., Greenman, E., & Farkas, G. (2010). Legal status and wage disparities for Mexican immigrants. Social Forces, 89(2), 491–513.

Heyman, J. M. (2014). “Illegality” and the U.S.-Mexico border: How it is produced and resisted. In C. Menjívar & D. Kanstroom (Eds.), Constructing immigrant “illegality” (pp. 111–137). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hoefer, M., Rytina, N. & Baker, B. (2012). Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2011. Department of Homeland Security. Washington, DC: Office of Immigration Statistics.

Kanstroom, D. (2007). Deportation nation: Outsiders in American history. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kinchelow, J., Frates, J., & Brown, E. R. (2007). Determinants of children’s participation in California’s Medicaid and SCHIP programs. Health Services Research, 42(2), 847–866.

Landale, N. S., Thomas, K. J. A., & Van Hook, J. (2011). The living arrangements of children of immigrants. The Future of Children, 21(1), 43–70.

Lebrun, L. A. (2012). Effects of length of stay and language proficiency on health care experiences among immigrants in Canada and the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 74(7), 1062–1072.

Lee, S., Brown, E. R., Grant, D., Berlin, T., & Brick, J. M. (2009). Exploring nonresponse in a health survey using neighborhood characteristics. American Journal of Public Health, 99(10), 1811–1817.

Lee, J., Goldstein, M., Brown, E. R., & Ballard-Barbash, R. (2010). How does acculturation affect the use of complementary and alternative medicine providers among Mexican- and Asian-Americans? Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 12(3), 302–309.

Leerkes, A., Leach, M. A., & Bachmeier, J. D. (2012). Borders behind the border: An exploration of state-level differences in migration control and their effects on U.S. migration patterns. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(1), 111–129.

Marrow, H. B., & Joseph, T. D. (2015). Excluded and frozen out: unauthorized immigrants’ (non)access to care after US health care reform. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(14), 2253–2273.

Massey, D. S., & Tourangeau, R. (2013). Where do we go from here? Nonresponse and social measurement. The Annals, 645, 185–221.

National Research Council. (2009). Reengineering the survey of income and program participation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Okie, S. (2007). Immigrants and health care—At the intersection of two broken systems. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(6), 525–529.

Oropesa, R. S., Landale, N. S., & Hillemeier, M. M. (2015). Family legal status and health: Measurement dilemmas in studies of Mexican-origin children. Social Science and Medicine, 138, 57–67.

Ortega, A. N., Fang, H., Perez, V. H., Rizzo, J. A., Carter-Pokras, O., Wallace, S., & Gelberg, L. (2007). Health care access, use of services, and experiences among undocumented Mexicans and other Latinos. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167(21), 2354–2360.

Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2011). Unauthorized immigrant population: National and state trends, 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Passel, J. S., Cohn, D., & Rohal, M. (2014). Unauthorized immigrant totals rise in 7 states, fall in 14: Decline in those from Mexico fuels most state decreases. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Perez, V. H., Fang, H., Inkelas, M., Kuo, A., & Ortega, A. N. (2009). Access to and utilization of health care by subgroups of Latino children. Medical Care, 47(6), 695–699.

Pew Research Center. (2012). Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. The Pew Research Center: Washington, DC. http://www.people-press.org/2012/05/15/assessing-the-representativeness-of-public-opinion-surveys/.

Prentice, J. C., Pebley, A. R., & Sastry, N. (2005). Immigration status and health insurance coverage: Who gains? Who Loses? American Journal of Public Health, 95(1), 109–116.

Rodriguez, N., & Paredes, C. (2014). Coercive immigration enforcement and bureaucratic ideology. In C. Menjívar & D. Kanstroom (Eds.), Constructing immigrant “illegality”: Critiques, experiences, and responses (pp. 63–83). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenblum, M. R., & Meissner, D. (2014). The deportation dilemma: Reconciling tough and humane enforcement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Schrag, P. (2006). California: America’s high-stakes experiment. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Scott, G. & Ni, H. (2004). Access to health care among Hispanic/Latino Children: United States, 1998–2001. Advance data from vital and health statistics. Number 344. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Simanski, J. F. (2014). Immigration enforcement actions: 2013. Annual Report. Washington, D.C.: Department of Homeland Security.

Stevens, G. D., Rice, K., & Cousineau, M. R. (2007). Children health initiatives in California: The experiences of local coalitions pursuing universal coverage for children. American Journal of Public Health, 97(4), 738–743.

Stevens, G. D., West-Wright, C. N., & Tsai, K. (2010). Health insurance and access to care for families with young children in California, 2001–2005: Differences by immigration status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 12, 273–281.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2012). A Guide to Naturalization. http://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/article/M-476.pdf Accessed on May 11, 2015).

USC/Los Angeles Times. (2012). New University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences/Los Angeles Times Poll, October 15–21. http://www.gqrr.com/articles/2012/10/24/new-university-of-southern-california-dornsife-college-of-letters-arts-and-sciences-los-angeles-times-poll-2/

USC/Los Angeles Times. (2013). New University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences/Los Angeles Times Poll, March 21. http://www.gqrr.com/articles/2013/03/21/new-university-of-southern-california-dornsife-college-of-letters-arts-and-sciences-los-angeles-times-poll-6/

Vargas, E. D. (2015). Immigration enforcement and mixed-status families: The effects of risk of deportation on Medicaid use. Children and Youth Services Review, 57, 83–89.

Vargas Bustamante, A., Fang, H., Rizzo, J. A., & Ortega, A. N. (2009). Understanding observed and unobserved health care access and utilization disparities among US Latino adults. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(5), 561–577.

Vargas-Bustamante, A., Fang, H., Garza, J., Carter-Pokras, O., Wallace, S., Rizzo, J., & Ortega, A. (2012). Variations in healthcare access and utilization among Mexican immigrants: The role of documentation status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(1), 146–155.

Wallace, S. P., Mendez-Luck, C., & Castaneda, X. (2009). Heading South: Why Mexican immigrants in California seek health services in Mexico. Medical Care, 47(6), 662–669.

Weathers, A. C., Minkovitz, C. S., Diener-West, M., & O’Campo, P. (2008). The effect of parental immigrant authorization on health insurance coverage for migrant Latino children. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10(3), 247–254.

Yoshikawa, Hirokazu. (2011). Immigrants raising citizens: Undocumented parents and their young children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Yu, S. M., Huang, Z. J., Schwalberg, R. H., & Nyman, R. M. (2006). Parental English proficiency and children’s health services access. American Journal of Public Health, 96(8), 1449–1455.

Ziol-Guest, K. M., & Kalil, A. (2012). Health and medical care among the children of immigrants. Child Development, 83(5), 1494–1500.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NICHD Grants 5P01HD062498-04 and R24HD041025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oropesa, R.S., Landale, N.S. & Hillemeier, M.M. Legal Status and Health Care: Mexican-Origin Children in California, 2001–2014. Popul Res Policy Rev 35, 651–684 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9400-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9400-6