Abstract

Academia and political campaigners conventionally cast gender stereotypes as an electoral liability for women in politics. Incongruent stereotype expectations place women in a double-bind where they either fail the social demands of political leadership or they breach gender norms related to femininity—with potential backlash due to stereotype violation in both cases. Two decades of research offer conflicting conclusions regarding the role of stereotype incongruity in candidate evaluations and its electoral consequences for women in politics. This paper theoretically revisits and empirically tests core assumptions of stereotype incongruity as a driver of gender biases in political communication. In a series of four online survey experiments, this study examines incongruity in trait expectations (study 1), trait inferences (studies 2 and 3), and trait evaluations (study 4). Results show that voters expect and infer incongruity in candidate traits for women and men politicians only in few but notable cases. Moreover, voters punish candidates of both gender groups similarly for displaying stereotypically undesirable traits but reward female politicians more strongly for displaying desirable communal traits. The findings have important implications for the understanding of persistent biases that women face in electoral politics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advice on how political candidates should and should not present themselves on the campaign trail is significantly attuned to their gender (Bauer & Santia, 2022; Grumbach et al., 2022). Academic literature, political campaigners, and conventional wisdom cast traits and qualities deemed desirable for political leaders as overlapping with stereotypical expectations of masculinity but colliding with norms of femininity (Eagly, 2007; Heilman et al., 2004; Koenig et al., 2011). Women entering the masculine domain of politics risk backlash from perceived incongruity between gender and leadership roles; as they either stick or break with one set of role expectations, they are devalued because they are perceived as either lacking in femininity or lacking in leadership (Ditonto et al., 2014; Herrnson et al., 2003; Schneider et al., 2022). How women best navigate incongruent stereotype expectations thus represents a major concern for their strategic communication and, ultimately, their electoral success and representation in positions of political decision-making.

Voters rely heavily on candidate traits in their candidate evaluations (Bauer, 2020; Fridkin & Kenney, 2011), yet the available evidence offers mixed and conflicting guidance on how women should emphasize which traits on the campaign trail (for meta-analytic review see Bauer & Santia, 2022; Rohrbach et al., 2023). Although the disconnect of leadership and gender stereotypes is central to the literature of gender and politics (Holman et al., 2016; Schneider & Bos, 2014, 2019), there is currently limited understanding of when incongruent role expectations emerge in the candidate evaluation process and how different types of incongruity translate into voter prejudice.

The goal of this paper is to theoretically and empirically disentangle stereotype incongruity to better understand how stereotypical expectations shape the evaluations of political candidates. First, it draws from and extends Role Congruity Theory (Eagly & Karau, 2002) to distinguish three different role incongruity effects in the candidate evaluation process—namely, in the expectation, inference, evaluation of candidate traits. It then empirically examines the extent of gender bias in all three types of stereotype incongruity in a series of four original survey experiments (Ntotal = 4012).

The results show that voters hold similar abstract stereotypes of female politicians and women in general but view male politicians as less communal and more agentic than female politicians (study 1). These trait expectations do not trigger stereotypical trait inferences when concrete politicians are described with textual gender cues (study 2). However, voters tend to infer incongruent traits following candidate descriptions with visual gender cues (study 3). Moreover, voters punish candidates of both gender groups similarly for displaying stereotypically undesirable traits but reward female politicians more strongly for displaying desirable communal traits (study 4). Women’s emphasis of communal traits emerges as a viable strategy on the campaign trail, which can both reap electoral benefits while mitigating the risk of backlash due to gender norm transgressions.

Role Incongruity Effects in the Candidate Evaluation Process

Various concepts in the literature of gender and leadership describe the apparent disconnect in voter expectations of female leaders. For example, “think manager—think male”, “double bind” or “damned if they do, damned if they don’t” situations (Bauer, 2015; Brooks, 2013; Koenig et al., 2011) all emphasize the issue of conflicting stereotypes and the incongruent role expectations that they contain. Two decades ago, Eagly and Karau (2002) systematized this disconnect in stereotype expectations in their role congruity theory (RCT). RCT construes role incongruity as the tendency of people to have “dissimilar beliefs about leaders and women and similar beliefs about leaders and men” (Eagly & Karau, 2002, p. 575). Because voters have a masculine image of politics, encountering feminine gender cues in political contexts will “disrupt this image” and affect their “processing and evaluation of political messages” (Ditonto et al., 2014; Domke et al., 2000, p. 400). As voters observe women as occupants of two social roles, woman and political leader, they combine the diverging role expectations by means of “weighted averaging” (p. 575): The more accessible gender cues are and the more incongruent expectations voters must combine, the higher the probability of bias against women leaders (see also Bauer, 2015, 2020; Rudman et al., 2012; Schneider & Bos, 2019; Schneider et al., 2022). In sum, voters must reconcile diverging expectations for women politicians while they can readily integrate gender and leadership expectations for men politicians.

Stereotypical expectations about the appropriateness of traits for male and female politicians can be organized by two distinctions: trait dimension and trait desirability (see Table 1 for a 2 × 2 summary of stereotypical traits). The first distinction differentiates between a communal and agentic dimension of traits. Beliefs about women—but not about men and leaders—are rooted in communality, which includes traits like helpfulness, kindness, warmth, and cooperation. In contrast, beliefs about men and leaders—but not about women—pertain to agentic traits, such as competence, self-reliance, confidence, and ambition (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014; Fiske et al., 2002).

Second, traits vary in their social desirability within both dimensions. On the one hand, prescriptions are generally desirable traits that are appreciated and rewarded across social groups. Prescriptions are connected to gender and leadership norms respectively because the desirability is intensified for traits that are role congruent and relaxed for traits that are role incongruent (Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010; Prentice & Carranza, 2002; Saha & Weeks, 2022). Accordingly, women should be high in communality but can be high in agency; men and leaders should be high in agency but can be high in communality. On the other hand, proscriptions denote traits that encompass normatively undesirable qualities that induce penalization. The desirability of proscriptive traits follows the inverse pattern. Women are allowed to be low in communality (e.g., gullible, timid, emotional) but should not be low in agency (e.g., rebellious, stubborn, commandeering); men and leaders are allowed to be low in agency but should not be low in communality. Another way to think of the relationship between desirable and undesirable traits is that they are internally correlated endpoints of a continuum within each trait dimension (see also Fiske et al., 2002). For example, due to the intensified gender norm for men to be assertive and dominant (desirable agentic traits), voters may excuse rebelliousness or commandeering tendencies (undesirable agentic traits) as byproducts of that same norm.

Two issues have obscured the seamless integration of RCT in literature on gender and candidate evaluation. A minor gap concerns the dearth of explicit comparisons of how gender norms related to the desirability of traits combine with role incongruity. One set of studies has investigated how women can overcome incongruity by emphasizing desirable leadership traits (Bauer, 2017; Swigger & Meyer, 2019) whereas another set has studied backlash from displaying undesirable traits (Cassese & Holman, 2018; Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010).

The second and more consequential shortcoming results from the lack of process-oriented perspectives on role incongruity. By focusing on which traits result in role incongruity, past research on candidate evaluation has neglected the question of when and how incongruity emerges at different stages of the candidate evaluation process (see also Bauer, 2013, 2015). Applying RCT to the candidate evaluation process, incongruity in role expectations can emerge at three different stages: (1) in voters’ general expectations of how traits are related to gender and leadership roles, (2) in their inferences of traits upon encountering individuals occupying these roles, and (3) in their way of combining role-based information to form evaluations of politicians displaying stereotypical traits. The candidate evaluation process comprises all these steps although most studies conflate them or focus on a single type of incongruity and treat the others as untested assumptions. These conceptual unclarities have contributed to heterogeneous empirical evidence that resists more definitive conclusions regarding the role of incongruent expectations on voter attitudes towards women candidates (Rohrbach et al., 2023; Schneider & Bos, 2014). Moreover, addressing these gaps is important because predictions about potential gender bias are likely to vary depending on what type of incongruity effect on what type of trait expectation is considered.

The remainder of this section will conceptualize incongruity effects at each stage of the candidate evaluation process by revisiting the existing literature on gender and candidate evaluations. An overview of the theoretical expectations that are then empirically tested is presented in Table 2.

Stage 1: Incongruity in Trait Expectations

Preceding the evaluation process of specific politicians, voters have a priori expectations of how female and male politicians should and should not be. These trait expectations reflect voters’ stereotype knowledge; that is, their collectively shared beliefs about social roles that are acquired as a result of gendered political socialization (Bos et al., 2022; Miller et al., 2009). Incongruity in trait expectations arises in political contexts because of the overlap in desirable and undesirable traits is greater between occupants of the masculine and political leadership role than for occupants of the feminine and political leadership role (Eagly, 2007). For example, Schneider and Bos (2014) showed that voters expect very similar traits in male politicians and men in general. Yet they also find that voters have dissimilar views about the desirability of traits for female politicians and women in general. Constituting their own subtype of feminine stereotype, female politicians are thus subject to a distinct set of desirable and undesirable traits. This subtype is disadvantageous for female politicians as it defines them “more by their deficits than their strengths” (p. 260), lacking both the desirable feminine traits (i.e., high communality) and desirable leadership traits (i.e., high agency). Although a recent update of their foundational study showed a positive evolution in voters’ stereotypical views of women politicians (Van der Pas et al., 2023), I follow the more established perspective and posit the following expectations. Incongruity in trait expectations for female politicians is thus characterized by a simultaneous incongruity with the feminine and leadership role: Relative to women, female politicians are seen as cold; relative to male politicians, they are seen as incompetent (Bligh et al., 2012; Saha & Weeks, 2022).

Incongruent trait expectations (H1) Voters expect female politicians to have (a) more undesirable agentic traits than women in general, (b) less desirable agentic traits than male politicians, but also (c) less desirable communal traits than women in general.

Stage 2: Incongruity in Trait Inferences

A key assumption in literature on gender stereotyping is that voters rely on stereotypical knowledge (see stage 1) to specific politicians when forming political judgements. This second stage describes how voters infer different traits based on candidate gender, representing the baseline gender difference that anchors further information processing about specific politicians (see Ditonto et al., 2014). Incongruity in trait inferences is thus parallel to the notion of stereotype activation—it is the extent to which voters process candidate messages with feminine (instead of leadership) role expectations in mind (see Bauer, 2015; Kunda & Spencer, 2003). Gender stereotypical patterns in media coverage (e.g., focus on feminine traits or women’s appearance) as well as emphasis on visual information in political campaigning heighten the saliency of gender cues from which voters readily draw inferences about candidate attributes (Bauer & Carpinella, 2018). These repeated and cumulative associations of women politicians with gender role cues reinforce gender as a relevant category for political judgements (Coronel et al., 2021).

According to RCT, these tendencies serve as “factors that increase the weight given to the female gender role, as opposed to the leader role” (Eagly & Karau, 2002, p. 578), especially in low information contexts (Banducci et al., 2008). There is currently little evidence on incongruity in stereotypical trait inferences in candidates’ campaign communication. I thus draw mainly from the outlined theoretical framework in suggesting the following expectations. Specifically, I posit that voters infer desirable and undesirable traits in female politicians that align with gender role but not leadership role expectations. Moreover, gender differences in trait inferences should be exacerbated if gender cues are especially salient.

Incongruent trait inference (H2) In absence of other individuating information, voters will spontaneously infer less (a) undesirable and (b) desirable agentic traits but more (c) undesirable and (d) desirable communal traits for female than male politicians.

Stage 3: Incongruity in Trait Evaluations

Research on gender and candidate evaluation most commonly invokes stereotype incongruity to explain gender-differentiated effects of a range of candidate traits on voters’ evaluation outcomes (Bauer, 2015, 2020; Cassese & Holman, 2018). These mostly experimental studies focus on incongruity in evaluation outcomes; that is, they trace how voters combine expectations induced by communal (feminine) and agentic (masculine) traits differently for female and male politicians. This third stage thus involves the evaluative component that is at the core of stereotype application (Kunda & Spencer, 2003). The different combinations of stereotype traits and candidate gender result in three types of incongruity effects: (1) full congruity with both gender and leadership stereotypes, (2) partial incongruity with either leadership or gender stereotypes, and (3) full incongruity with both stereotypes.

Because politics is a masculine domain (e.g., Saha & Weeks, 2022), full congruity should result in the most advantageous evaluations and marks the general rule that is reserved for male candidates with desirable agentic traits. Much more exceptional are contexts of full incongruity that link male politicians to undesirable communality.

Partial incongruity, however, is the default for female politicians who must choose between either violating leadership or gender norms. On the one hand, women politicians may successfully break with gender norms by foregrounding leadership-congruent agency. For example, messages emphasizing desirable agentic traits (e.g., competent and assertive) can increase female candidates’ perceived issue competence, leadership qualities, likeability, and electoral support (Bauer, 2017; Bos, 2011; Karl & Cormack, 2023). These results are consistent with RCT, which predicts that prejudice diminishes if women can establish their qualifications as leaders (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Rudman et al., 2012). Yet any agency rewards that women may receive should be smaller relative to those of (fully congruent) men. Crucially, any such potential gains may be outweighed by backlash from associations with undesirable agentic traits (e.g., rebellious and aggressive). Indeed, research has consistently linked “cold” women to strong penalties (Boussalis & Coan, 2021; Cassese & Holman, 2018; Heilman et al., 2004; Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010; Saha & Weeks, 2022; Schneider et al., 2022). In contrast, little backlash is expected for male politicians, as these traits map onto the expected “cold but competent” stereotype of political leaders (Bligh et al., 2012; Fiske et al., 2002; Rudman et al., 2012). In sum, I follow the notion of the well-documented double-bind and expect that female politicians win less with agency-based strategies relative to male politicians but are likely to lose more:

Gender-incongruent evaluations (H3) Voters (a) penalize undesirable agentic traits more and (b) reward desirable agentic traits less in female than male politicians.

On the other hand, existing research suggests that women can gain from sticking to the communality-based expectations of feminine stereotypes. Research has found more favorable evaluations for female politicians who highlight desirable communal traits (e.g., cooperative and kind) and “run as women” relative to male politicians (Bast et al., 2022; Herrnson et al., 2003; Karl & Cormack, 2023). Yet female politicians risk penalization from associations with leadership-incongruent undesirable communality (e.g., yielding and timid), because such traits prompt voters to cast doubts on women’s political qualifications (Bauer, 2020). As dominant gender norms may encourage voters to excuse undesirable communal traits in female (but not male) politicians (Prentice & Carranza, 2002), the magnitude of this penalty is likely to be smaller than for male politicians. In the following, I follow and extend evidence of a potential “feminine advantage” on gender-congruent domains and posit that communality-based strategies result in better evaluations for female than male politicians for both desirable and undesirable traits:

Leadership-incongruent evaluations (H3) Voters (c) penalize undesirable communal traits less and (d) reward desirable communal traits more in female than male politicians.

Experimental Analysis of Stereotype Incongruity Effects

The goal of the empirical strategy is to disentangle stereotype incongruity effects in a series of four online survey experiments. The first study investigates incongruity in voters’ stereotype knowledge by conceptually replicating findings of two prominent studies on trait expectations of three social groups: female politicians, male politicians, and women in general (study 1; see Prentice & Carranza, 2002; Schneider & Bos, 2014). The next two studies focus on stereotype activation by assessing incongruity in voters’ spontaneous inferences of stereotypical traits in candidates following textual (study 2) and visual (study 3) gender cues. The last study examines stereotype application as incongruity in the effects of stereotypical candidate traits on voter evaluations in the United States (Study 4).

All studies share the same conceptualization of trait measures and rely on similar experimental stimuli. This makes it possible, for the first time, to compare the extent of incongruity at different stages of the candidate evaluation process and thus shed light on how and when incongruity translates into gender bias in voter evaluations. Moreover, I employ a Bayesian framework for the analysis of each study to derive probabilistic comparisons of both presence and absence of each type of stereotype incongruity. The four studies were conducted consecutively.Footnote 1 All sample size justifications, materials, and analyses were pre-registered before the data collection of each study. All materials including code and data are available on the Open Science Framework server (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/WNQB4).Footnote 2

Study 1: Incongruity in Trait Expectations

The first study conceptually replicates the designs of two prominent studies on trait stereotype knowledge (Prentice & Carranza, 2002; Schneider & Bos, 2014) to assess to what extent trait expectations of female politicians are (in) congruent with those of male politicians and women in general. Both pioneering studies come with three limitations: (1) their data collections now date back more than one and two decades—a time span in which gender stereotypes have changed significantly (Eagly et al., 2020; van der Pas et al., 2023); (2) they both relied on rather small student samples, with 208 and 127 participants for the two studies by Prentice & Carranza and 284 participants in the study by Schneider and Bos (2014); (3) both studies included rating tasks with very long trait lists, risking responder fatigue. In the following, I detail how I combine both studies into a single design and address these concerns. Note, however, that the goal of this first study is not a direct replication of the two studies but to provide an updated empirical baseline for the traits voters associate with different social groups.

Participants

2033 participants (40% women, Mage = 39.9, SDage = 16.6) were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk in November 2022.Footnote 3 As the study investigates expectations of trait desirability in American society, study participation was limited to workers with a registered location in the United States. This focus on the US context was chosen for better comparisons of the results to the original studies (Prentice & Carranza, 2002; Schneider & Bos, 2014). Pay for the study participation (Q2 = 4.4 min) was 0.75 USD.

Procedure and Materials

Like Prentice and Carranza (2002), I asked participants to rate the desirability of traits for (1) women, (2) men, and (3) a person (without corresponding gender label). I used a between-subjects rather than a within-subjects design like in their original studies due to concerns of measurement error related to fatigue. Like Schneider and Bos (2014), I also included (4) female politicians, (5) male politicians, and (6) politicians (without corresponding gender label) as additional groups for comparisons.Footnote 4 The combination thus yielded a between-subject design with the target group as a single factor and a total of six conditions.

Instructions informed participants that they are about to rate members of American society on a range of attributes. In line with the original studies, the instructions emphasized that the survey is not interested in people’s personal endorsement of stereotypical beliefs but in their expectations of these beliefs in general (wording adapted from Schneider & Bos, 2014). Participants then rated their target group in seven blocks on a series of traits adapted from Prentice and Carranza (see Figure D2.2 in the Online Appendix for a list of traits). Each block consisted of ten traits, containing each five traits relating to agency and communality respectively. Five blocks contained desirable traits and two blocks contained undesirable traits. The instruction for the trait rating task reads as follows: “How desirable is it in American society for a [woman/female politician/male politician] to possess each of the following characteristics?” The instructions were repeated at the top of each block with the target group printed in bold.

Measures

Participants rated the desirability of 70 traits for their target group in randomized order on a scale from 1 (very undesirable) to 9 (very desirable; see Prentice & Carranza, 2002). In addition to the single items, I averaged groups of five traits into four separate scales to form measures of desirable agency (rational, ambitious, self-reliant, decisive, competitive), desirable communality (sensitive, loyal, cooperative, kind, polite), undesirable agency (aggressive, arrogant, self-righteous, controlling, obstinate), and undesirable communality (yielding, impressionable, shy, weak, emotional). These specific items were chosen because they showed the largest gender differences in the study by Prentice and Carranza (2002). A pilot study (n = 105) showed satisfactory reliability (ω > 0.75 and Greatest Lower Bound > 0.8) for all four scales. An exploratory factor analysis suggested that all twenty traits indeed cluster into four distinct factors. All outcomes were zero-centered before the analysis.

In addition, I controlled for participant ideology (two items on a scale from 1 left/liberal to 10 right/conservative), gender, age, and gender essentialism (eight items; Swigger & Meyer, 2019).

Analysis

The goal of the analysis is to compare voters’ trait expectations of three groups: female politicians (reference group), women in general, and male politicians. As a first step, I conduct a series of two-tailed Bayesian t-tests for each individual trait and pair of groups (for descriptive results see Fig. 4 in the Online Appendix due to limited space). As a second step, I test for differences between the groups for each trait scale by fitting separate linear Bayesian regression models, with target group as a categorical predictor.

We visually report estimated posterior distributions for all three groups together with their respective medians and with 95% Credible Intervals (CrI). As a test for evidence for or against the hypotheses, I will calculate and report Bayes factors (BF). BF describe two models’ predictive performance in relation to each other—that is, they are calculated as the ratio of the likelihood of the evidence in favor of the presence of an effect over the likelihood of the evidence of the absence of an effect, given the data (e.g., Keysers et al., 2020).

We employ Bayesian inference for its ability to quantify evidence for and against the null hypothesis. Unlike traditional frequentist frameworks, which primarily uncover gender differences, Bayesian methods also consider the absence of differences (i.e. gender similarities). In the context of diminishing overt biases against women and men candidates (e.g., Schwarz & Coppock, 2022), investigating similarities is crucial to avoid reinforcing potentially harmful assumptions about gender differences (see Hyde, 2014; Rohrbach et al., 2023).

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the extent of incongruity in voters’ trait expectations of female politicians, male politicians, and women in general. On the one hand, the results show little difference in trait desirability between female politicians and women in general. Contrary to my expectations, voters do not expect female politicians to be less communal than women in general, which is indicated by similar trait ratings of both undesirable (BF10 = 0.85; H1a) and desirable communal traits (BF10 = 1.46; H1c).

Posterior distributions of trait expectations for female politicians, women, and male politicians. Dots represent posterior median along with 95% (thick) and 66% (thin) credible intervals (CrI). Darker (lighter) colors indicate the probability of values that are higher (lower) than the posterior median of female politicians (Color figure online)

On the other hand, the results show incongruity in voters’ expectations of desirable—but not undesirable—traits between female and male politicians. Participants rate male politicians as slightly higher in desirable agentic traits (BF10 = 3.79), which is in line with the original study (Schneider & Bos, 2014) and my expectation of partially incongruent trait expectations (H1b). Although I did not hypothesize this difference, I find that, in turn, voters expect higher desirable communal traits for female than male politicians (BF10 = 6.34). Unlike the original study, this analysis suggests that voters have very similar trait expectations between female politicians and women in general. Like the original study, voters’ stereotypes differ somewhat between female and male politicians, but these differences are not evidently to women’s disadvantage.Footnote 5

Studies 2 and 3: Incongruity in Trait Inferences

The first study showed that voters indeed have different trait expectations for the general categories of female and male politicians (but not between female and women in general). The next two studies investigate to what extent these differences in trait expectations are activated when they process information about politicians as concrete instances of social roles. Both studies assess incongruity in the way voters spontaneously infer personality traits on the basis of textual (study 3) or visual (study 4) gender cues in low information contexts.

Participants

For study 2, 506 participants (37% women, Mage = 38.5, SDage = 13.0) were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk in August 2022. Study 3 consisted of 398 participants (40% women, Mage = 38.9, SDage = 16.6) who were recruited on Amazon Mechanical Turk in Ocotber 2022. Pay for the study participation (Q2S3 = 4.0 min, Q2S4 = 3.8 min) was 0.5 USD. Both samples were limited to US American participants.

Procedure and Materials

Instead of manipulating stereotypical traits as separate conditions, the next two studies treat them as outcomes to assess gender differences in trait inferences. Both studies manipulate candidate gender (woman vs. man) as a single between-subjects factor. Both conditions instruct participants to carefully read a (fictional) newspaper article that they are about to see. The short newspaper stimulus is about the performance of a candidate for the Senate at a local rally, is neutral in tone and did not include any otherwise qualifying information.

Study 2 uses the textual manipulation of candidate gender via first name, Patricia or Patrick Baker, and corresponding pronouns. Study 3 additionally includes a candidate portrait to add a visual gender cue. Highlighting the centrality of visual information for trait inferences, Coronel et al., (2021, p. 282) note that textual gender cues “may underestimate the extent to which gender stereotypes influence political judgments given that […] people extract gender-category information from text instead of images of faces”. The two chosen portraits depict British members of parliament with neutral facial expressions. The images were pre-tested and used in a previous study and are statistically indistinguishable in terms of perceived attractiveness, MPatricia = 4.47, MPatrick = 4.56, d = -0.032, and competence, MPatricia = 4.58, MPatrick = 4.50, d = 0.033.

Study 2 thus tests the conservative scenario in which voters must infer candidate traits based on minimal gender cues. Study 3 emulates the more realistic setting of actual media coverage or campaign advertisements where textual and visual information is combined to render gender cues more salient.

Measures

Both studies capture trait inferences using the same trait scales from the first study. The instructions were changed to ask participants to rate on a 9-point Likert scale to what extent candidate Baker possessed each of the twenty traits. All scales were zero-centered before the analysis. The same control variables as in the previous studies were measured.

Analysis

The goal of the analysis is to assess gender differences in voters’ trait inferences following neutral media messages. I quantify the overlap of the distributions in both gender groups by calculating an overlapping index \(\widehat{\eta }\) (Pastore & Calcagnì, 2019), which is defined as the common area under two probability density functions and ranges from 0 (= no overlap between distributions) to 1 (= identical distributions). The normalized index reflects the similarity—or difference (1 − \(\widehat{\eta }\))—as the percentage of overlap in the distribution of trait inferences between the woman and man candidate. I additionally test for differences (or similarities) by means of robust Bayesian estimation of groups (Kruschke, 2013). Built as a Bayesian extension of a frequentist t-test, this approach uses a t-distribution to estimate of group medians and standard deviations, along with a normality parameter describing the heavy-tailedness of the t-distribution. I use the same reporting strategy as in previous studies.

Results

Figure 2 depicts voters’ inferences of stereotypical traits in candidates in absence of other individuating information. The results for study 2 suggest that textual gender cues do not result in incongruent trait inferences. Instead, the strong overlaps in trait inferences for the woman and man candidate (all \(\widehat{\eta }\) > 0.9) show that voters make similar baseline assumptions about women and men’s desirable and undesirable personality traits (BF10 between 0.96 and 1.93 for all outcomes).

In line with RCT, the salience of gender cues seems to condition the potential for incongruity in role expectations. Compared to textual cues, these visual cues in study 3 resulted in more dissimilar inferences in traits of female and male politicians across all four measures. The pattern is identical to incongruity in trait expectations from study 1: Gender differences in trait inferences align with gender role expectations but only for desirable traits. Inferences about female politicians are higher in desirable communal (\(\widehat{\eta }\) = 0.76, BF10 = 3.54; H2d) but not lower in undesirable communal traits (\(\widehat{\eta }\) = 0.88, BF10 = 1.31: H2c). Conversely, voters infer more desirable (\(\widehat{\eta }\) = 0.81, BF10 = 3.20; H2b) but not less undesirable agentic traits (\(\widehat{\eta }\) = 0.87, BF10 = 1.22; H2a) in male than female politicians. However, the evidence for the presence of incongruent trait inference is moderate and effect sizes are rather small.

Study 4: Incongruity in Trait Evaluations

So far, the empirical analysis has established that voters do have general incongruent expectations for desirable for female and male politicians (study 1) and that these expectations can to some extent result in incongruent trait inferences in specific politicians (studies 2 and 3). The last study examines how voters apply stereotypical expectations in their evaluations of politicians who display stereotypical traits. This last stage of the evaluation process thus examines incongruity in trait evaluations.

Participants

For study 4, 1075 US participants (36% women, Mage = 38.8, SDage = 13.9) were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk in March 2022. Pay for the study participation (Q2S1 = 4.3 min, Q2S2 = 5.2 min) was 0.75 USD.

Procedure and Materials

To examine incongruity in the effect of being associated with desirable and undesirable traits for women and men candidates, participants were randomly assigned to one of eight conditions. Each condition of the 2 (candidate gender: woman or man) × 4 (ascribed stereotype trait: undesirable agency, desirable agency, undesirable communality, or desirable communality) design instructs participants to carefully read the same (fictional) newspaper article from the previous studies. Candidate gender is again manipulated by their first name, Patrick or Patricia Baker, and the repeated use of their corresponding gendered personal pronouns.

Rather than treating personality traits as outcomes, I now include the items of the four scales as manipulations in the mock newspaper article in the form of adjectives and short phrases (see study1 for a list of traits). I combine different sources of trait ascriptions—the undefined reporter of the article, an audience member of the rally, and unnamed political experts —to rule out potential source effects and to create the impression that there is some form of consensus regarding the candidate’s personality. For example, the journalist describes the candidate as making either a strong, warm, intimidating, or timid appearance at a local rally in the opening paragraph.

A pilot study on Amazon Mechanical Turk (n = 105) investigated the manipulation of the trait conditions (no control) for the woman candidate as a within-subjects factor. Every participant scored the vignettes on the four scales that reflect the four trait manipulations (using items not used in the manipulation). Each condition was indeed rated highest on its corresponding scale, indicating successful manipulation of the traits.

Measures

Study 4 uses the standard feeling thermometer on a scale from 1 to 100 as a measure of participants’ global candidate evaluation (Holman et al., 2016; Swigger & Meyer, 2019). Because voters may feel favorable towards the candidate but choose to strategically withhold support for the candidate because they perceive their chances at winning of being too small (Bateson, 2020), I additionally capture assessments of candidate viability with three items from previous research (Brooks, 2013). Participants rated on a four-point Likert scale (1) how electable they think the candidate is, (2) how likely they think the candidate is going to win the elections, and (3) how qualified they think the candidate is to be a senator. All outcomes were zero-centered before the analysis. The same control variables form the previous studies were measured.

Analysis

The goal of the analysis is to assess gender differentiated responses to candidates displaying stereotypical traits of varying incongruity. To do so, I fit separate Bayesian linear multivariate regressions for all outcome measures. I visually report estimated posterior medians along with 95% credible intervals (CrI) for all interaction effects between candidate gender and the stereotype trait condition.

Results

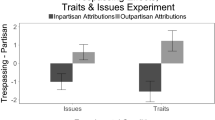

The desirability of candidate traits affects voter evaluations across studies and outcomes. Figure 3 shows that voters reward desirable traits with favorable but punish undesirable traits with unfavorable evaluations. To what extent does this pattern differ across gender lines? In the following, I test for a difference in evaluations of female and male politicians within the trait conditions.

We first turn to agentic traits that are incongruent with gender norms for female politicians. Contrary to expectation (H3b), voters similarly reward female and male politicians emphasizing desirable agentic traits (e.g., assertive and competent; BF10 = 0.5). I find no evidence for gender differences in evaluations of viability for desirable agency (BF10 = 0.7). In line with my expectation (H3a), voters tend to punish female politicians more strongly for possessing undesirable agentic qualities that collide with their gender norm (e.g., stubborn and intimidating). Specifically, voters report lower thermometer ratings for the female politician displaying these traits (BF10 = 2.0) and rate her as less viable than their male counterpart (BF10 = 4.5). In summary, voters accept women with desirable agentic traits but penalize them more strongly than men for having undesirable agentic traits.Footnote 6

A similarly mixed pattern arises for women’s communality-based strategies that are incongruent with leadership traits. Describing politicians with desirable communal traits (e.g., kind and caring) produces similarly favorable evaluations of vote preference (BF10 = 0.20) and viability (BF10 = 2.81) regardless of candidate gender. This finding does not support the expectation of stronger rewards for women politicians whose messages are congruent with gender norms (H3d) Finally, there is only little evidence for the expectation that voters are more lenient with female than male politicians with undesirable communal traits (e.g., timid and yielding; H3c). Voters show no gendered vote preference (BF10 = 2.69) or viability assessments (BF10 = 0.39). In sum, voters disproportionately reward desirable communality in female politicians but tend to dislike undesirable communal traits irrespective of gender.Footnote 7

Overall Discussion

Incongruent role expectations influence voters’ evaluations of female and male politicians differently at different stages of the evaluation process, but only conditionally so. The results suggest three overall patterns. First, the evidence across all four studies suggests that stereotype incongruity effects emerge only in few cases and—in most cases—with small magnitudes. One interpretation consistent with RCT would be that incongruity decreases as the gender distribution in occupants of leadership role evens out (Eagly, 2007; Rudman et al., 2012). With more women elected into political office around the world than ever before (Hinojosa, 2021), societal views of women have more favorable on leadership-relevant traits (Eagly et al., 2020; van der Pas et al., 2023). This pattern further adds to recent evidence showing that gender similarities are the norm while gender differences represent the exception (Bridgewater & Nagel, 2020; Rohrbach et al., 2023; Saha & Weeks, 2022; Schwarz & Coppock, 2022).

Second, voters show heightened expectations of communality. Voters generally expect female politicians to be more communal than their male counterparts (study 1) and infer more communality in concrete (but fictional) candidates (study 3). This strong prescription of communality for women candidates is consistent with changing gender stereotypes of women in general: Not only have women retained their advantage in communality over time, but this gap has even widened in the last decades (Eagly et al., 2020; van der Pas et al., 2023). Crucially, this surplus of communality directly links to evaluation outcomes, as women who are kind and caring fare better in terms of vote preference and perceived viability than men (study 4). Whereas some studies support the “feminine advantage” in candidates’ direct communication (Bauer, 2020; also see Bast et al., 2022), recent meta-analysis suggests that communality-based media reporting can also yield unfavorable evaluations (Rohrbach et al., 2023).

Third, voter expectations tend to diverge on desirable but converge on undesirable trait. Studies 1 and 3 yield some evidence of incongruity in the expectation and inference of desirable but not of undesirable traits, thus highlighting the empirical and theoretical importance of distinguishing between desirable and undesirable traits (Bauer, 2017). This pattern indicates that voters may value different virtues in male and female politicians but expect them to have similar vices. From a stereotype process perspective, this could mean that desirable traits are more central in gender stereotype knowledge and, in turn, also more effective in stereotype activation. An alternative explanation is that undesirable qualities are evaluated affectively rather than substantively, which results in negative global judgements that cut across gender lines (Fridkin & Kenney, 2011; Rohrbach, 2022). Moreover, the final study suggests little gendered backlash in response to undesirable communal traits. However, the findings do illustrate—as the only gender difference in undesirable traits—the well documented penalty faced by women who are associated with undesirable agentic traits (Boussalis & Coan, 2021; Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010; Schneider et al., 2022). When it comes to stereotype proscriptions, female politicians pay a much heavier price for being incongruent with gender rather than leadership norms.

What do these findings imply for stereotype incongruity as a causal mechanism of gendered candidate evaluation? If I look at the different types of incongruity in sequence, the patterns of effects suggest a strong parallel to models of candidate evaluation that focus on the role of affect (e.g., Lodge & Taber, 2013). As information that is incongruent with prior attitudes produces negative affect (Bakker et al., 2021), the initial presence (or absence) of incongruity could act as an affective anchor for further downstream processes, namely in trait inference and trait evaluation (see also Rohrbach, 2022). This affective account of stereotype incongruity could explain all three patterns. In the finding of gender similarities, the small extent of incongruity in trait expectation does not elicit negative affect and remains inconsequential for trait inference and evaluation. For the intensified expectation of communality, the positive congruity with gender norms outweighs or pre-empts potential negative affect arising from incongruity with leadership norms (e.g., failure to establish leadership or agency). Finally, undesirable traits are associated with negative affect for all candidates, overriding any additional influence of gender cues.

Conclusion

This paper first theoretically disentangled stereotype incongruity by distinguishing role incongruity effects in trait expectations, inferences, and evaluations and by differentiating between trait dimension (agency/communality) trait desirability (desirable/undesirable). This reconceptualization of stereotype incongruity reconciles conflicting findings of past studies and derives succinct explanations of voters’ conditional backlash (and reward) from incongruent candidate messages. The theoretical expectations were then empirically in a series of four survey experiments.

The overall finding of gender similarities adds to recent work pushing for a paradigm shift in how I approach gender bias in political communication (Hyde, 2014; Rohrbach et al., 2023). Growing bodies of research document little overt bias in the electorate (Bridgewater & Nagel, 2020; Schwarz & Coppock, 2022) and in candidates’ personality and qualifications (Anzia & Berry, 2011; Bernhard & de Benedictis-Kessner, 2021) that would explain women’s underrepresentation. Consequently, it is no longer enough to blame sexist voters or a lack of ambition in women candidates. Accepting gender similarities as a default can help calibrate research on the multitude of drivers in context and structure that produce and uphold difference (Fowler & Lawless, 2009).

The single clear pattern that emerges across studies is a pronounced expectation of women to be communal (e. g., warm, cooperative, loyal). This finding has implications for women on the campaign trail. It corroborates past findings that women candidates can safely and strategically use communal traits in their campaign messages (Bast et al., 2022; Bauer, 2020; Bauer & Santia, 2022). This paper showed that incongruity with leadership norms does not hurt women candidates as long as they ensure congruity with gender stereotypical expectations. This incongruity tradeoff means that women’s boost in communality can translate into actual electoral advantages, as people rely more strongly on evaluations of communal than agentic traits in their opinion formation of political candidates (Laustsen & Bor, 2017) and people in general (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014).

This series of studies comes with at least four limitations. First, this project relied on well-powered but non-representative online samples which constrains the generalizability of its insights. Second, this analysis omitted the role of partisanship in candidate evaluations to better isolate gender effects. Extant research has investigated the interaction of gender and partisan cues (e.g., Cassese & Holman, 2018; Schneider & Bos, 2016; Van Der Pas et al., 2022), but it remains unclear how these different cues link to the different types of role incongruity outlined in this study. Second, part of the explanatory power of RCT derives from its integration of moderating influences on incongruent role expectations (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Heilman et al., 2004). As instances of such influences, this paper varied the salience of gender cue for trait inferences and internally replicated the trait evaluations in a second national contexts.Footnote 8 Yet more work is needed to understand how different types of incongruity effects are conditioned by other aspects, such as electoral context or individual differences in voters (for a discussion see Schneider & Bos, 2019). Finally, I distinguish three types of incongruity and briefly discuss—but do not test—how they causally relate to each other in the candidate evaluation process. Future research could integrate affect in RCT and investigate its role as a potential causal conduit connecting different types of incongruent role expectations, ideally combining a range of explicit and implicit measures (Bakker et al., 2021; Lodge & Taber, 2013). This paper has undertaken efforts to shed light on how incongruent stereotypical expectations shape evaluations of political candidates. Disentangling stereotype incongruity is a small but crucial step to better understand women’s knotty trajectories in a changing political sphere.

Data Availability

Replication files (data, code, documentation) are available on the Open Science Framework server (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/WNQB4).

Notes

Note that the manuscript reports the empirical studies in inverse sequence to better map onto the theoretical framework. The original empirical strategy started, like most studies on gender and candidate evaluation, with incongruity in trait evaluations. It then sought to disentangle incongruity effects by “reverse-engineering” the candidate evaluation process, focusing on trait inferences second and trait expectations last.

The Online Appendix also includes a list of minor points in which the manuscript deviates from the study pre-registrations.

In all studies, I employed several strategies to mitigate problems associated with the use of online survey pools such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (e.g., Necka et al., 2016). First, I did not impose eligibility criteria other than a 90% approval rate to discourage worker deception based on demographic information. Second, I pre-registered two attention checks and filtered out double failures during data cleaning. Third, I excluded cases with unrealistically rapid response rates.

In the present study only the comparisons between female politicians, male politicians, and women in general are of interest.

I do not include a comparison of results to the original study by Prentice and Carranza (2002), because their analysis is not within the scope of this paper.

Exploratory subgroup analyses showed that it is mostly men (but not women) participants who punish the woman politician for displaying undesirable agentic traits. I report a summary and detailed results of the role of participant gender in section E3.1 on the online appendix.

One explanation of these findings might be the specific stereotypical expectations held by participants in the United States. To test the robustness of the trait evaluation patterns, I conducted an internal replication of study 4 on a sample of 1272 participants from the UK (50% women, Mage = 34.4, SDage = 13.5). As an English-speaking country with a bipartisan political system, I was able to use the same materials and only slightly modify the survey to match the UK context. The pattern of results converges across studies, indicating that incongruity affects trait evaluation in similar ways in the US and UK context. One exception is that UK participants report less tolerance of undesirable traits in candidates of both gender groups, which is showcased by their more negative evaluations. I report the full results of this additional fifth study in the online appendix (see in particular section C).

See previous footnote and additional study 5 reported in the online appendix.

References

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Chapter four—communal and agentic content in social cognition: A dual perspective model. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 195–255). Academic Press.

Anzia, S. F., & Berry, C. R. (2011). The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson effect: Why do congresswomen outperform congressmen? American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 478–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00512.x

Banducci, S., Karp, J. A., Thrasher, M., & Rallings, C. (2008). Ballot photographs as cues in low-information elections. Political Psychology, 29(6), 903–917. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00672.x

Bakker, B. N., Schumacher, G., & Rooduijn, M. (2021). Hot politics? Affective responses to political rhetoric. American Political Science Review, 115(1), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000519

Bast, J., Oschatz, C., & Renner, A.-M. (2022). Successfully overcoming the “double bind”? A mixed-method analysis of the self-presentation of female right-wing populists on instagram and the impact on voter attitudes. Political Communication, 39(3), 358–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.2007190

Bateson, R. (2020). Strategic discrimination. Perspectives on Politics, 18(4), 1068–1087. https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272000242X

Bauer, N. M. (2013). Rethinking stereotype reliance: Understanding the connection between female candidates and gender stereotypes. Politics and the Life Sciences, 32(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.2990/32_1_22

Bauer, N. M. (2015). Emotional, sensitive, and unfit for office? Gender stereotype activation and support female candidates. Political Psychology, 36(6), 691–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12186

Bauer, N. M. (2017). The effects of counterstereotypic gender strategies on candidate evaluations. Political Psychology, 38(2), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12351

Bauer, N. M. (2020). A feminine advantage? Delineating the effects of feminine trait and feminine issue messages on evaluations of female candidates. Politics & Gender, 16(3), 660–680. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000084

Bauer, N. M., & Carpinella, C. (2018). Visual information and candidate evaluations: The influence of feminine and masculine images on support for female candidates. Political Research Quarterly, 71(2), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917738579

Bauer, N. M., & Santia, M. (2022). Going feminine: Identifying how and when female candidates emphasize feminine and masculine traits on the campaign trail. Political Research Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912921102025

Bernhard, R., & de Benedictis-Kessner, J. (2021). Men and women candidates are similarly persistent after losing elections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2026726118

Bligh, M. C., Schlehofer, M. M., Casad, B. J., & Gaffney, A. M. (2012). Competent enough, but would you vote for her? Gender stereotypes and media influences on perceptions of women politicians. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(3), 560–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00781.x

Bos, A. L. (2011). Out of control: Delegates’ information sources and perceptions of female candidates. Political Communication, 28(1), 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.540306

Bos, A. L., Greenlee, J. S., Holman, M. R., Oxley, Z. M., & Lay, C. J. (2022). This one’s for the boys: How gendered political socialization limits girls’ political ambition and interest. American Political Science Review, 116(2), 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001027

Boussalis, C., & Coan, T. G. (2021). Facing the electorate: Computational approaches to the study of nonverbal communication and voter impression formation. Political Communication, 38(1–2), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1784327

Bridgewater, J., & Nagel, R. U. (2020). Is there cross-national evidence that voters prefer men as party leaders? No. Electoral Studies, 67, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102209

Brooks, D. J. (2013). He runs, she runs: Why gender stereotypes do not harm women candidates. Princeton University Press.

Cassese, E. C., & Holman, M. R. (2018). Party and gender stereotypes in campaign attacks. Political Behavior, 40(3), 785–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9423-7

Coronel, J. C., Moore, R. C., & deBuys, B. (2021). Do gender cues from images supersede partisan cues conveyed via text? Eye movements reveal political stereotyping in multimodal information environments. Political Communication, 38(3), 281–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1763530

Ditonto, T. M., Hamilton, A. J., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2014). Gender stereotypes, information search, and voting behavior in political campaigns. Political Behavior, 36(1), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9232-6

Domke, D., Lagos, T., Lapointe, M., Meade, M., & Xenos, M. (2000). Elite messages and source cues: Moving beyond partisanship. Political Communication, 17(4), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600050179013

Eagly, A. H. (2007). Female leadership advantage and disadvantage: Resolving the contradictions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00326.x

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., & Sczesny, S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of US public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist, 75(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000494

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Fowler, L. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2009). Looking for sex in all the wrong places: Press coverage and the electoral fortunes of gubernatorial candidates. Perspectives on Politics, 7(3), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709990843

Fridkin, K. L., & Kenney, P. J. (2011). The Role of candidate traits in campaigns. The Journal of Politics, 73(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000861

Grumbach, J. M., Sahn, A., & Staszak, S. (2022). Gender, race, and intersectionality in campaign finance. Political Behavior, 44(1), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09619-0

Heilman, M. E., Wallen, A. S., Fuchs, D., & Tamkins, M. M. (2004). Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.416

Herrnson, P. S., Lay, C. J., & Stokes, A. K. (2003). Women running “as women”: Candidate gender, campaign issues, and voter-targeting strategies. The Journal of Politics, 65(1), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00013

Holman, M. R., Merolla, J. L., & Zechmeister, E. J. (2016). Terrorist threat, male stereotypes, and candidate evaluations. Political Research Quarterly, 69(1), 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912915624018

Hyde, J. S. (2014). Gender similarities and differences. In Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115057

Karl, K. L., & Cormack, L. (2023). Big boys don’t cry: Evaluations of politicians across issue, gender, and emotion. Policalt Behavior, 45(2), 719–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09727-5

Keysers, C., Gazzola, V., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2020). Using Bayes factor hypothesis testing in neuroscience to establish evidence of absence. Nature Neuroscience, 23(7), 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0660-4

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 616–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023557

Kruschke, J. K. (2013). Bayesian estimation supersedes the t test. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2), 573. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029146

Kunda, Z., & Spencer, S. J. (2003). When do stereotypes come to mind and when do they color judgment? A goal-based theoretical framework for stereotype activation and application. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4), 522–544. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.522

Laustsen, L., & Bor, A. (2017). The relative weight of character traits in political candidate evaluations: Warmth is more important than competence, leadership and integrity. Electoral Studies, 49, 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2017.08.001

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. Cambridge University Press.

Miller, C. F., Lurye, L. E., Zosuls, K. M., & Ruble, D. N. (2009). Accessibility of gender stereotype domains: Developmental and gender differences in children. Sex Roles, 60(11), 870–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9584-x

Necka, E. A., Cacioppo, S., Norman, G. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2016). Measuring the prevalence of problematic respondent behaviors among MTurk, campus, and community participants. PLoS ONE, 11(6), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157732

Okimoto, T. G., & Brescoll, V. L. (2010). The price of power: Power seeking and backlash against female politicians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(7), 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210371949

Pastore, M., & Calcagnì, A. (2019). Measuring distribution similarities between samples: A distribution-free overlapping index. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1089. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01089

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(4), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Rohrbach, T. (2022). Loud and negative: Exploring negativity in voter thoughts about women and men politicians. Politics & Governance, 10(4), 374–383. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v10i4.5752

Rohrbach, T., Aaldering, L., & Van Der Pas, D. J. (2023). Gender differences and similarities in news media effects on political candidate evaluations: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 73(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqac042

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Glick, P., & Phelan, J. E. (2012). Chapter four—reactions to vanguards: Advances in backlash theory. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 167–227). Academic Press.

Saha, S., & Weeks, A. C. (2022). Ambitious women: Gender and voter perceptions of candidate ambition. Political Behavior, 44(2), 779–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09636-z

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Political Psychology, 35(2), 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12040

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2016). The intersection of party and gender stereotypes in evaluating political candidates. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 37(3), 274–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2016.1188598

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2019). The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Political Psychology, 40(1), 173–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12573

Schneider, M. C., Bos, A. L., & DiFilippo, M. (2022). Gender role violations and voter prejudice: The agentic penalty faced by women politicians. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 43(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2021.1981095

Schwarz, S., & Coppock, A. (2022). What have we learned about gender from candidate choice experiments? A meta-analysis of sixty-seven factorial survey experiments. The Journal of Politics, 84(2), 655–668. https://doi.org/10.1086/716290

Swigger, N., & Meyer, M. (2019). Gender essentialism and responses to candidates’ messages. Political Psychology, 40(4), 719–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12556

Van Der Pas, D. J., Aaldering, L., & Steenvoorden, E. (2022). Gender bias in political candidate evaluation among voters: The role of party support and political gender attitudes. Frontiers in Political Science, 4, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.921252/full

Van der Pas, D., Aaldering, L., & Bos, A. L. (2023). Looks like a leader: Measuring evolution in gendered politician stereotypes. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09888-5

Hinojosa, M. (2021). The Descriptive Representation of Women in Politics. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, I thank Daphne van der Pas, members of the Hot Politics Lab at the University of Amsterdam, panels at the 2023 annual conferences of the Swiss Political Science Association, The Swiss Association of Communication and Media research as well as the International Communication Association.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Fribourg. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Informed Consent

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The questionnaires (including informed consent form) and methodology for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Management, Economics, and Social Sciences of the University of Fribourg (Application No. 2021–12-01).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rohrbach, T. Are Women Politicians Kind and Competent? Disentangling Stereotype Incongruity in Candidate Evaluations. Polit Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09956-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09956-4