Abstract

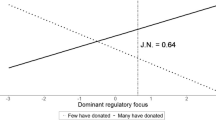

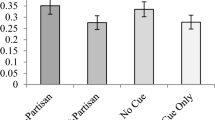

Electoral campaigns are increasingly reliant on small donations from individual donors. In this work, we examine the influence of racial and partisan social descriptive norms on donation behavior using a randomized field experiment. We find that partisan identity information treatments significantly increase donation behavior, while racial identity information has only small and insignificant effect compared to the control. We find, however, significant variation by racial status. For minorities, information about the behavior of other donors in their racial group is as powerful or more powerful than information about co-partisan behavior, while white respondents are much more responsive to information about co-partisan behavior than to information about co-racial behavior. Our results show that partisan and racial identity based social normative information can have a strong effect on actual donation behaviors and how these normative motivations vary across racial groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

We are open to share our data for replications.

Notes

Magleby et al. (2018) estimate that between 9 and 10 (12 and 13) million donors gave to federal campaigns, committees and PACs in 2008 (2012), most being small dollar donors.

Social norms can be differentiated into injunctive and descriptive norms (Cialdini et al., 1990). Injunctive norms refer to “what others want us to do or … avoid doing,” and compliance to injunctive norms is often associated with social enforcement and monitoring. However, descriptive norms refer simply to what others actually do. People use descriptive norms as decisional shortcut and conform to descriptive norms, in the absence of enforcement and monitoring, because their desire to live successfully (Cialdini and Trost 1998). Our study focuses on the effects of descriptive norms rather than injunctive norms.

Older studies of donation behavior identify three main benefits to donors: purposive, solidary, and material benefits (Francia et al., 2003; Wilson 1974). Recent work, however, “finds little evidence…for material (an individual or group benefit) or solidary (sociability and prestige) reasons for giving” (Magleby et al., 2018, p. 27).

Previous studies have used social information (Broockman and Kalla, 2022; Ou and Tyson 2021), such as the money raised by another candidate (Augenblick and Cunha 2015; Green et al., 2015) or money donated by neighbors (Perez-Truglia and Cruces 2017), but have not examined racial or political identity as potential motivators.

These works are limited in their attempts to estimate the effect of partisan social normative information. Perez-Truglia and Cruces (2017) focus on neighbors and only examine presidential campaign donations over $200. Augenblick and Cunha (2015) only test the effect of messages coming from a single campaign on that campaign’s fundraising.

The precise identification of how descriptive social normative information prompts giving is beyond the scope of our design. While our treatments highlight descriptive behaviors of others in ways consistent with other work on social norms (e.g., Gerber and Rogers 2009; Hassell and Wyler 2019), we cannot exclude the possibility that our experimental interventions may prompt other considerations such as expressive motivations (Magleby et al., 2018; Schuessler 2000). Information about descriptive norms could work because they create social expectations for behavior (Cialdini and Goldstein 2004) or because they help solve coordination problems (Lewis 1969). Unable to differentiate between these two pathways here, this is an area ripe for future work.

Our hypotheses are preregistered and available at EGAP registry (https://osf.io/bz53e).

The messages did not favor any particular candidate, political party, or political organization.

Florida’s nickname, the Sunshine State, is said to refer both to weather and regulations governing transparency.

Florida sunshine laws mandate publicizing donors’ addresses allowing us to match survey respondents from the voter file to donation records. Bulk data from the FEC, in contrast, only provides the city and zip code thus inhibiting such precise matching.

Diversity statistics at the state and national level are available at https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/racial-and-ethnic-diversity-in-the-united-states-2010-and-2020-census.html.

See Appendix A3 for additional details of the survey.

Only one registered voter from each address was selected for the study to limit spillover (or multiple forms of the treatment) from one experimental subject to another.

We note that there was no overlap between the respondents of the two surveys.

More information about the Florida voter file is available at https://dos.myflorida.com/elections/for-voters/voter-registration/voter-information-as-a-public-record/.

We limit our experiment to survey respondents in part because we knew, given their response to the survey, that the email in the voter file was active. Although our measure is still an intent to treat effect, because we know these email inboxes were being regularly monitored we can be more confident in measuring treatment effects.

More information about how we determine and categorize participants’ racial identity is available in the Appendix A2.

Based on Florida campaign finance records, 3.2% of individuals in the control group, 3.6% in the partisan identity group, and 2.9% in the racial identity group donated in the 2018–2020 election cycle. We compare the proportion of previous donors using two-tailed t-tests and none are statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. When we focus on previous donors, we compare donation frequency and amount using equality of median tests. These pre-treatment differences are also not significant.

Future work should consider whether or not independent leaners respond similarly to partisan social norms.

Treatment emails were sent from a university email account while the invitations for the original survey were sent by the survey research firm. Thus, there was no association between the two emails that would lead respondents to believe they were connected.

The emails were non-partisan and did not promote any particular candidate or party.

The information about the amount and frequency of donations given to subjects in our study is derived from the self-reported information collected in Phase 1. We note that there are differences between subjects’ reports about their behavior and their actual behavior as reported in Florida’s campaign finance data. The difference may be the result of individuals over-reporting political contributions because giving is socially desirable or because they gave to candidates outside of Florida which would not be in the Florida campaign finance data. Importantly, however, the information regarding the frequency and amount of donation is a range value consistent across treatments and should not affect the identification of treatment effects.

FEC bulk data also does not provide donors’ specific addresses in their bulk data, limiting our ability to match subjects to donations.

Indeed, the average and median donation amount to Florida campaigns of those who donated after the treatment was substantially smaller than $200.

According to Florida’s laws, any political donation (even as small as $0.01) in Florida is recorded. We identified whether and when a subject donated from public information available at https://dos.elections.myflorida.com/campaign-finance/contributions/.

We used individuals’ first name, last name, street number, and zip code as identifiers to match to public records.

Importantly, since we focus on the average treatment effects, the identified effects are equally valid using three-weeks or ten-weeks as the time window. However, it should be noted that we may risk lose informative data by using a shorter time window. Hence, in our analysis, we tested both 3-week and 10-week time windows.

Another question is whether our treatments changed who respondents gave to. Unfortunately, we cannot identify this effect because our treatments reinforce the previous behavior of donors. Before as well as after our treatments, donors gave to candidates who shared the same partisanship or ethnic group, or both, which is consistent with previous research (see Grumbach and Sahn 2020).

Most people, 97% of our sample, had never donated to Florida state-level campaigns. We do not have reliable records regarding whether our sample donated to candidates outside of Florida or to federal campaigns in Florida. We discuss more about this in the conclusion.

Appendix B.3 in the Online Appendix presents the calculations of statistical power. We focus on the analysis of treatment effects caused by partisan identity based social norm. At the aggregate level, the identified effects are sufficiently statistically powerful at the conventional level (i.e., greater than 0.8).

As noted when we describe our results, we also conduct the Mann–Whitney Wilcoxon test as a robustness check, since it takes the ranks of each observation into account and is thus more powerful than the median test (Siegel 1956).

Individuals in the partisan identity descriptive social norm group gave nine donations (a total of $449.33 in which one donor gave $250 and the others gave on average $24.8) while individuals in the control group gave only one donation ($25).

Six donors in the racial identity group contributed a total of $49.

A caveat is that our study is based on a relatively small sample. When we break down the analysis by ethnic and racial status, the power of the effects is between 0.67 and 0.71, which is somewhat underpowered. In order to partially address this issue, we report the results of the non-parametric Fisher–Pitman permutation tests as a robustness check. The non-parametric Fisher–Pitman permutation tests rely on fewer and weaker assumptions and have the highest power (100%) compared to related tests (Siegel 1956). Using a Monte Carlo study, Moir (1998) shows permutation tests have statistically reliable power for as few as eight observations per treatment category. In all of our analysis there are more than eight observations per treatment category.

Based on the data of the 10-week time window, about 38% of minorities in the racial identity social norm treatment donated compared to 0% in the control group. The difference is statistically significant both under t test (p = 0.008) and permutation test (p = 0.042).

Because we might be concerned the fact that blacks are highly likely to be Democrats (and thus are reacting to a partisan cue rather than a racial cue), we also examined the results only for Hispanic/Latinos (who are much more divided along partisan lines in Florida). We find the same directional effects with further reduced statistical power.

Our estimates may even further underestimate the effect because giving at the state level is smaller than the federal level donation given the national media exposure and the nationalization of politics in recent years.

References

Abrajano, M., & Hajnal, Z. L. (2015). White backlash. Princeton University Press.

Anoll, A. (2022). The obligation mosaic: Race and social norms in US political participation. University of Chicago Press.

Ansolabehere, S., De Figueiredo, J. M., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2003). Why is there so little money in US politics? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(1), 105–130.

Augenblick, N., & Cunha, J. M. (2015). Competition and cooperation in a public goods game: A field experiment. Economic Inquiry, 51(1), 574–588.

Barber, M., & Eatough, M. (2020). Industry politicization and interest group campaign contribution strategies. Journal of Politics, 82(3), 1008–1025.

Berinsky, A. J. (1999). The two faces of public opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 43(4), 1209–1230.

Berinsky, A. J. (2005). The perverse consequences of electoral reform in the United States. American Politics Research, 33(4), 471–491.

Bonilla, T., & Tillery, A. B. (2020). Which identity frames boost support for and mobilization in the #BlackLivesMatter movement? An experimental test. American Political Science Review, 114(4), 947–962.

Broockman, D. E., & Kalla, J. L. (2022). When and why are campaigns’ persuasive effects small? Evidence from the 2020 US presidential election. American Journal of Political Science, 67(4), 833–849.

Broockman, D. E., Kalla, J. L., & Sekhon, J. S. (2017). The design of field experiments with survey outcomes: A framework for selecting more efficient, robust, and ethical designs. Political Analysis, 25(4), 435–464.

Broockman, D. E., & Malhotra, N. (2020). What do partisan donors want? Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 104–118.

Burt, C., & Popple, J. S. (1998). Memorial distortions in donation data. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(6), 724–733.

Chandra, K. (2006). What is ethnic identity and does it matter? Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 397–424.

Cialdini, R. B., Demaine, L. J., Sagarin, B. J., Barrett, D. W., Rhoads, K., & Winter, P. L. (2006). Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Social Influence, 1(1), 3–15.

Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015.

Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske & G. Lidzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, 4th ed., pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

Condon, M., Larimer, C. W., & Panagopoulos, C. (2016). Partisan social pressure and voter mobilization. American Politics Research, 44(6), 982–1007.

Dawson, M. C. (1994). Behind the mule: Race and class in African-American politics. Princeton University Press.

DellaVigna, S., List, J. A., Malmendier, U., & Rao, G. (2016). Voting to tell others. The Review of Economic Studies, 84(1), 143–181.

Enos, R. D. (2016). What the demolition of public housing teaches us about the impact of racial threat on political behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 60(1), 123–142.

Enos, R. D., Fowler, A., & Vavreck, L. (2014). Increasing inequality: The effect of GOTV mobilization on the composition of the electorate. Journal of Politics, 76(1), 1–288.

Francia, P. L., Green, J. C., Herrnson, P. S., Powell, L. W., & Wilcox, C. (2003). The financiers of congressional elections: Investors, ideologues and intimates. Columbia University Press.

Frey, B. S., & Meier, S. (2004). Social comparisons and pro-social behavior: Testing “conditional cooperation” in a field experiment. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1717–1722.

Garcia Bedolla, L., & Michelson, M. R. (2012). Mobilizing inclusion: Transforming the electorate through get-out-the-vote campaigns. Yale University Press.

Gerber, A., & Rogers, T. (2009). Descriptive social norms and the motivation to vote: Everybody’s voting and so should you. Journal of Politics, 71(1), 178–191.

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 472–482.

Grant, J. T., & Rudolph, T. J. (2002). To give or not to give: Modeling individuals’ contribution decisions. Political Behavior, 24(1), 31–54.

Green, D. P., Krasno, J. S., Panagopoulos, C., Farrer, B., & Schwam-Baird, M. (2015). Encouraging small donor contributions: A field experiment testing the effects of nonpartisan messages. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(2), 183–191.

Grier, K. B., & Munger, M. C. (1993). Comparing interest group PAC contributions to House and Senate incumbents, 1980–1986. Journal of Politics, 55(3), 615–643.

Grumbach, J. M., & Sahn, A. (2020). Race and representation in campaign finance. American Political Science Review, 114(1), 206–221.

Grumbach, J. M., Sahn, A., & Staszak, S. (2022). Gender, race, and intersectionality in campaign finance. Political Behavior, 44(2), 319–340.

Hassell, H. J. G. (2022). Local racial context, campaign messaging, and public political behavior: A congressional campaign field experiment. Electoral Studies, 69, 102247.

Hassell, H. J. G., & Quin Monson, J. (2014). Campaign targets and messages in campaign fundraising. Political Behavior, 36(2), 359–376.

Hassell, H. J. G., & Wyler, E. E. (2019). Negative descriptive social norms and political action: People aren’t acting, so you should. Political Behavior, 41(1), 231–256.

Hill, S. J., & Huber, G. A. (2017). Representativeness and motivations of the contemporary donorate: Results from merged survey and administrative records. Political Behavior, 39(1), 3–29.

Holbein, J. B., & Hassell, H. J. G. (2019). “When your group fails: Race and information responsiveness. Journal of Public Administration and Theory, 29(2), 268–286.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Karp, J. A., & Brockington, D. (2005). Social desirability and response validity: A comparative analysis of overreporting voter turnout in five countries. Journal of Politics, 67(3), 825–840.

Kessler, J. B. (2017). Announcements of support and public good provision. American Economic Review, 107(12), 3760–3787.

Klar, S. (2013). The influence of competing identity primes on political preferences. Journal of Politics, 75(4), 1108–1124.

Landa, D., & Duell, D. (2015). Social identity and electoral accountability. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 671–689.

LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. actions. Social Forces, 13(2), 230–237.

Lewis, D. (1969). Convention: A philosophical study. Harvard University Press.

Magleby, D. B., Goodliffe, J., & Olsen, J. A. (2018). Who donates in campaigns? The importance of message, messenger, medium, and structure. Cambridge University Press.

Moir, R. (1998). A Monte Carlo analysis of the Fisher randomization technique: Reviving randomization for experimental economists. Experimental Economics, 1(1), 87–100.

Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., & Torres, M. (2018). How conditioning on posttreatment variables can ruin your experiment and what to do about it. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 760–775.

Morton, R., & Ou, K. (2019). Public voting and prosocial behavior. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 6(3), 141–158.

Morton, R. B., Ou, K., & Qin, X. (2020). Reducing the detrimental effect of identity voting: An experiment on intergroup coordination in China. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 174, 320–331.

Murray, G. R., & Matland, R. E. (2014). Mobilization effects using mail: Social pressure, descriptive norms, and timing. Political Research Quarterly, 67(2), 304–319.

Ou, K., & Tyson, S. A. (2021). The concreteness of social knowledge and the quality of democratic choice. Political Science Research and Methods, 11(3), 483–500.

Panagopoulos, C. (2010). Affect, social pressure and prosocial motivation: Field experimental evidence of the mobilizing effects. Political Behavior, 32(4), 369–386.

Panagopoulos, C., Larimer, C. W., & Condon, M. (2014). Social pressure, descriptive norms, and voter mobilization. Political Behavior, 36, 451–469.

Parry, H. J., & Crossley, H. M. (1950). Validity of responses to survey questions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 14(1), 61–80.

Perez-Truglia, R., & Cruces, G. (2017). Partisan interactions: Evidence from a field experiment in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 125(4), 1208–1243.

Petrow, G. A., Transue, J. E., & Vercellotti, T. (2018). Do white in-group processes matter, too? White racial identity and support for black political candidates. Political Behavior, 40(1), 197–222.

Schnakenberg, K. E. (2013). Group identity and symbolic political behavior. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 9, 137–167.

Schuessler, A. A. (2000). A logic of expressive choice. Princeton University Press.

Shang, J., & Croson, R. (2009). A field experiment in charitable contribution: The impact of social information on the voluntary provision of public goods. The Economic Journal, 119(540), 1422–1439.

Siegel, S. (1956). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill.

Steck, L. W., Heckert, D. M., & Alex Heckert, D. (2003). The salience of racial identity among African-American and white students. Race and Society, 6(1), 57–73.

Thomsen, D. M., & Swers, M. L. (2017). Which women can run? Gender, partisanship, and candidate donor networks. Political Research Quarterly, 70(2), 449–463.

Valenzuela, A. A., & Michelson, M. R. (2016). Turnout, status, and identity: Mobilizing Latinos to vote with group appeals. American Political Science Review, 110(4), 615–630.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

White, I. K., & Laird, C. N. (2020). Steadfast Democrats: How social forces shape black political behavior. Princeton University Press

Wilcox, R. R. (2011). Introduction to robust estimation and hypothesis testing. Academic.

Wilson, J. Q. (1974). Political organizations. Basic Books.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The experiments and reported findings are not under review at any other journals and have not been previously published in any format.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank Paul Herrnson, Jake Grumbach, John Kuk, Joyce Ejukonemu, Ethan Busby, members at APSA Annual Meeting, MPSA Annual Meeting, and seminar audiences at Brigham Young University and Florida State University for invaluable feedback. We thank Braeden McNulty and Kwabena Fletcher for their helpful assistance. This study is pre-registered at EGAP registry (https://osf.io/bz53e). Supplementary material for this article is available in the Appendix in the online edition. Replication files are available in the Political Behavior Data Archive on Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E6ND6G). This research was reviewed and approved by the Florida State University Institutional Review Board. All errors remain the responsibility of the authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cyphers, K.H., Hassell, H.J.G. & Ou, K. Racial and Partisan Social Information Prompts Campaign Giving: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Polit Behav (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09902-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09902-w