Abstract

Contemporary and historical political debates often revolve around principles of federalism, in which governing authority is divided across levels of government. Despite the prominence of these debates, existing scholarship provides relatively limited evidence about the nature and structure of Americans’ preferences for decentralization. We develop a new survey-based measure to characterize attitudes toward subnational power and evaluate it with a national sample of more than 2000 American adults. We find that preferences for devolution vary considerably both across and within states, and reflect individuals’ ideological orientations and evaluations of government performance. Overall, our battery produces a reliable survey instrument for evaluating preferences for federalism and provides new evidence that attitudes toward institutional arrangements are structured less by short-term political interests than by core preferences for the distribution of state authority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Federalism is implicated in nearly every major policy debate in contemporary American politics. Policymaking activity on issues of immigration (Rodriguez, 2017), gun control (Lund, 2003), drug legalization (Chemerinsky et al., 2015), tax policy (Kincaid, 2017), health care (Gruber & Sommers, 2020), policing (Gerken, 2017), environmental regulation (Fitzgerald et al., 1988), and even foreign affairs (Goldsmith, 1997) is routinely contested on the basis of whether authority rests with national or state and local governments. The coronavirus pandemic and the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to reverse Roe v. Wade further sharpened debates about the division of power and responsibility across levels of government (e.g., Haffajee & Mello, 2020; Weisman, 2022). The salience and scope of the debate over federalism has led some observers to conclude that it is “without doubt, the most important political, legal, and constitutional debate taking place in America today, going to our very roots as a nation” (U.S. House, 1995).

Scholarship on federalism often debates whether and how it is associated with the quality of representative democracy. On the one hand, this literature finds that decentralized institutional arrangements create a more informed and involved public (Aidt & Dutta, 2017; Ordeshook & Shvetsova, 1995) and enhance selection (Myerson, 2006) and accountability mechanisms (Chhibber & Kollman, 2004). Other research, in contrast, argues that federalism is associated with higher rates of corruption (Treisman, 2000), reduced government responsiveness to public opinion (Soroka & Wlezien, 2010), and widening political inequality (Grumbach & Michener, 2022). While these studies reach mixed conclusions about the implications of federalism for citizen welfare, they do not study whether decentralization itself is consistent with citizens’ preferences over governing arrangements.

How do Americans view the allocation of power between national and state government? Existing scholarship offers several competing perspectives. One line of argument posits that preferences for local control are associated with traditional political orientations (e.g., Green & Guth, 1989), suggesting that individuals with more conservative ideologies are more supportive of decentralization. A second line of argument suggests that Americans support policymaking by the level of government that is most closely aligned with their own partisan affiliations and political interests (Dinan & Heckelman, 2020; Riker, 1964; Wolak, 2016). A third view argues that attitudes toward federalism reflect Americans’ relative trust for national versus local governing institutions (Hetherington & Nugent, 2001). Still other research suggests that evaluations of federal arrangements are shaped by the public’s experience with the quality of government across them (Gehring, 2021).

Despite the prominence of federalism in debates over the American political system, previous research provides relatively limited evidence about the nature and structure of preferences for decentralization. Empirical research on attitudes toward federalism has focused on the measurement of confidence assessments and approval ratings across levels of government or officials holding positions within them. These evaluations appropriately measure what Easton (1975, p. 437) termed “specific support,” but this research has largely neglected the measurement of diffuse support, or “a reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed or the effects of which they see as damaging to their wants” (Easton, 1965, p. 273). While specific support reflects short-term political evaluations, diffuse support characterizes more fundamental and longstanding attachments to institutional arrangements. We argue that the latter quantity provides a more appropriate assessment of the public’s views about the distribution of power across levels of government apart from their evaluations of contemporary political actors.

In this article, we develop a new survey-based measure to characterize Americans’ preferences for subnational power and evaluate it with a national sample of more than 2000 American adults. We validate the measure by demonstrating its relationship with respondents’ preferences for devolution across a number of policy domains. Using our new measure, we examine how attitudes toward subnational power reflect individuals’ partisan and ideological orientations, political context, and evaluations of government performance. We find that respondents do not evaluate questions of federalism merely as expressive partisans, and we find only limited evidence that attitudes toward federalism reflect the partisan context in which respondents live. Instead, views toward decentralization appear to reflect more deeply-rooted commitments to federal institutions and comparative evaluations of the performance of state governments. Overall, our battery produces a reliable survey instrument for measuring preferences for federalism and provides new evidence about public opinion on the allocation of power in a federal system.

Public Attitudes Toward Federalism

Federalism sits front and center in many of the most important debates in American political history. The Tenth Amendment attempted to assuage concerns among Anti-Federalists that the Constitution provided insufficient protections for the infringement of state sovereignty by the national government. Following the Civil War, Supreme Court jurisprudence routinely addressed the national government’s power to compel states to enforce the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. And in the last century, conflict over states’ rights and federal power has emerged over issues including civil rights, gender-based violence, interracial and same-sex marriage, abortion, gun control, and marijuana laws (for a selection of research on the role of states’ rights in party platforms and policy debates, see, e.g., Beienburg, 2018; Melder, 1939; Mettler, 2000; Mooney, 2000; Phillips, 1969; Stevens, 2002).

How does the American public view federalism? Survey data consistently show that Americans hold more positive views of state and local governance than they do of the national government. According to Pew Research Center (2018), for instance, two-thirds of Americans held favorable ratings of local government in 2018, and 58 percent viewed state government favorably, while only 35 percent provided favorable evaluations of the federal government. These data describe an American public with considerably greater esteem for local rather than national governing authorities.

We study how Americans view the balance of power between national and state government. Our focus on public preferences for federalism contributes to research that studies public attitudes toward political institutions and procedures (Becher & Brouard, 2022; Doherty & Wolak, 2012; Gibson, 1989; Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, 2002; Reeves & Rogowski, 2016, 2022). Attitudes about federalism may affect how Americans evaluate policy outcomes and political officials across levels of government. As Reeves and Glendening (1976, p. 135) explain, “The attitudes of the citizenry constitute one set of influences on a system’s movement along the centralization/decentralization continuum.” According to Kam and Mikos (2007, p. 623), moreover, “ordinary citizens play a role in policing the limits of federal power... because they value federalism.” In addition, attitudes about local control may be linked to behavioral outcomes, such as the use of violence against federal employees (Nemerever, 2021). Given the salience of federalism and its role in the U.S. political system, understanding public views on federalism provides insights into contemporary attitudes about American government.

How Americans Evaluate Federalism

Traditional theories of public opinion leave little room for the American public to hold meaningful attitudes toward federal arrangements. Most Americans evince relatively low levels of political knowledge (Campbell et al., 1960; Carpini & Keeter, 1996) and may have little interest in the details of federalism. According to Dahl (2002, p.115), attributing responsibility for policy decisions in a federal system is difficult “even for those who spending their lives studying politics,” and citizens often misattribute policy decisions to officials at different levels of government (Sances, 2017). These perspectives paint a dim portrait about the capacity of the American public to possess and express coherent preferences about the distribution of power in a federal system. Consistent with this conclusion, studies of federalism jurisprudence have argued that “no one besides the justices really cares about federalism” (Tushnet, 2005, p. 277).Footnote 1 Others argue, however, that Americans have “intuitive” beliefs about federalism (Schneider et al., 2011) that exhibit a “comprehensible structure” (Arceneaux, 2005, p. 311).Footnote 2

If Americans have genuine preferences over federalism, how are those preferences organized? A first perspective suggests that attitudes toward federalism could reflect more specific evaluations of officeholders and levels of government. For example, public preferences for federal arrangements could reflect their level of trust across levels of government. On this view, to the degree the public is more trusting of local government vis-à-vis national government, they support vesting policymaking authority in local officials rather than national policymakers. Consistent with this perspective, Hetherington and Nugent (2001) argue that trends in devolution during the 1980s and 1990s reflected the public’s greater trust in state governments relative to the national government.

Alternatively, attitudes toward federalism may be based in core beliefs about the distribution of authority across levels of government (e.g., Wolak, 2016). This view is reflected in the “federalist theory” of representation outlined by Arceneaux (2005, p. 300) which posits that citizens attribute policymaking responsibility to different levels of government and evaluate those governments on the basis of how well they perform those responsibilities. According to this perspective, beliefs about federalism reflect long-standing views about political structures rather than short-term or ephemeral political interests (on the distinction, see, e.g., Easton, 1975). For example, attitudes toward states’ rights may comprise a larger set of “traditional values” (Green & Guth, 1989, p. 50).

Evaluations of federalism may also reflect short-term political conditions. Individuals’ affinities for copartisan officials and/or their beliefs that copartisan officials better serve their interests could link the partisan composition to government with evaluations of federalism. For example, when the public’s preferred party controls national (but not local government), they may express greater support for centralizing power at the national level, and vice versa. Kolcak and McCabe (2021) provide evidence for this argument in the context of public support for federal intervention in states’ administration of the 2020 election. Previous research also indicates that Americans are more trusting of the national government when their preferred party is in power (Morisi et al., 2019), and scholarship on beliefs about devolution among both political elites (Goelzhauser & Rose, 2017; Stratford, 2018) and the mass public (Dinan & Heckelman, 2020; Wolak, 2016) indicates that these attitudes are associated with individuals’ partisan and political alignments with governing authorities.

Finally, preferences over federalism may be shaped by the public’s evaluations of government performance. To the extent Americans believe one level of government performs more effectively relative to others, Americans may support greater authority for the high performing level. Arceneaux (2005) terms this criterion the “causal-responsibility” attribution. This perspective suggests that, observing variation in policy performance across levels of government, the public endorses greater authority for the level of government they perceive as most effective. This perspective may further explain why preferences for federalism may vary across policy areas (Schneider et al., 2011; Thompson & Elling, 1999), as Americans perceive that some levels of government are more effective in addressing issues of transportation and schools while others are more effective in addressing economic and social policies.

Empirical Studies on Attitudes Toward Federalism

While previous scholarship provides a range of evidence in support of the perspectives outlined above, we argue and propose to rectify two persistent limitations of the empirical literature on public preferences for federalism. First, previous research has used inconsistent measurement approaches for studying attitudes toward federalism. Perhaps most commonly, attitudes about federalism have been studied using comparative measures of trust or confidence in various levels of government (e.g., Cole et al., 2004; Kincaid, 2017; Reeves & Glendening, 1976; Wlezien & Soroka, 2011). Other research studies preferences for federalism using measures of policy devolution (e.g., Dinan & Heckelman, 2020; Wolak, 2016). But because scholarship has tended not to jointly study trust (or confidence) and beliefs about devolution, it is unclear how to relate the findings from research that uses one approach but not the other.

Second, existing measurement approaches do not distinguish what Easton (1975) termed specific support from diffuse support. While measures of trust and confidence may be important indicators of affective evaluations, it is unclear whether they reflect short-term evaluations of institutional performance, approval of the officials serving in those levels of government, more durable views about the distribution of authority in a federal system, or something else altogether. Based on the distinction articulated by Easton (1975) in his conceptualization of regime support, these indicators are more akin to measures of specific support rather than diffuse support. While the former describes individuals’ satisfaction with the performance and outputs of current political authorities, the latter quantity characterizes one’s “commitment to an institution” (Easton, 1975, p. 437, p. 451). Just as, for instance, approval ratings of the current president are not synonymous with individuals’ beliefs about the institution of the presidency (e.g., Reeves & Rogowski, 2016), evaluations of contemporary governments may not be synonymous with preferences toward federalism. Because federalism describes a system of governance, we argue that diffuse support provides a more appropriate characterization of public beliefs about federalism than measures based on confidence assessments or approval ratings.

Given these limitations, existing literature provides an incomplete assessment of contemporary beliefs about federalism. This omission is surprising because previous research finds some evidence to suggest that the public has well-structured beliefs in this domain. In their work evaluating attitudes toward devolution, for instance, Schneider et al. (2011, p. 16) conclude that there is “a meaningful unifying characteristic (presumably, a psychological trait such as an attitude) generating the systematic structure” observed in their survey data. We contribute to this literature by focusing on the potential sources of this structure. We do so by developing a new battery to measure preferences for federalism and comparing it with attitudes about policy devolution and approval ratings across levels of government. These measures allow us to provide the most comprehensive evaluation to date of attitudes toward the American federal system.

Measuring Preferences for Federalism

We measured public views about the distribution of power between national and state governments using a battery we developed and fielded with an online survey of Americans in May 2020. The survey was carried out by Lucid, which used quota sampling to produce a sample that approximates the U.S. adult population with respect to gender, age, race and ethnicity, and Census region. A total of 2052 respondents completed the survey.

At the outset, we emphasize the limitations of using a non-probability sample to make generalizations about American public opinion. Table A.1 in the Appendix contains full demographic information about the sample. While the sample is broadly representative of the American population, it is also better educated, more white, and lower income than the country as a whole. So that the patterns in our data can be generalized to the demographic composition of the country, we construct sampling weights based on gender, age, race, Hispanic origin, educational attainment, income, and Census region. We apply these weights in the analyses reported below.Footnote 3 Nevertheless, we exercise caution in making descriptive inferences given the potential for differences between our sample and the national population on the basis of other (potentially unmeasured or unobservable) characteristics beyond those measured here.

Our survey contained three main components: (1) a series of randomly-ordered questions canvassing performance evaluations of state and local government, (2) a series of questions on devolution across a range of policy areas, and (3) a battery of randomly-ordered questions on more general attitudes towards federalism. In the rest of this section we describe this third battery of questions, which we call the federalism battery. Additionally, we present summary statistics for the measure and evaluate its properties.

Components of the Federalism Battery

Table 1 displays the text of the ten questions we used to develop the federalism battery. Following Schneider et al. (2011, Fig. 3), who collapse attitudes toward local and state government and distinguish them from attitudes toward national government, our questions focus specifically on the relationship between national and state government.Footnote 4 The first item reflects question wording used by the Pew Research Center and analyzed in previous scholarship on federalism (e.g., Dinan & Heckelman, 2020). The second, third, and fourth items reflect questions used by Schneider and Jacoby (2003). We devised the remaining items to measure other theoretically relevant aspects of federalism, including perceptions of the relative efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and innovative qualities of state government vis-à-vis the national government and support for state secession. Each question was answered on a four-point scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (4).Footnote 5 Table 1 collapses “strongly” and “somewhat” responses for the purpose of presentation, but we retain the full set of response options when constructing the composite measure of federalism preferences.

Respondents agreed with the items in the battery at varying rates, suggesting that our items provide a more nuanced assessment of attitudes toward federalism than any single indicator could. For example, about two-thirds of respondents agreed that “the federal government should run only those things that cannot be run at the state or local level,” similar to levels of support recorded in surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center and analyzed by Dinan and Heckelman (2020). Consistent with this view, the sample also reported high levels of agreement with statements that “the national government is involved with too many aspects of American society” (61 percent) and that “state governments should take on more responsibility” (84 percent). However, a large majority (79 percent) also agreed that “national government should do more to try and solve pressing problems.”Footnote 6

The new items we created further describe a public with relatively complex views about federalism. In asking respondents to comparatively evaluate the characteristics of state and local governments, we find that large majorities believed that state governments address problems faster (77 percent), more cost-effectively (68 percent), and with better ideas (81 percent) than the national government. Responses to other items suggest, however, that the public does not hold uniformly limited views about the role of the national government. For example, a majority endorsed the supremacy of national statutes relative to state law (59 percent) and disagreed that the federal government should only be responsible for military affairs (59 percent). Respondents were split about whether states should have the right to secede if they are dissatisfied with the national government (45 percent support, 55 percent oppose).Footnote 7 Overall, the patterns displayed in Table 1 provide new information about Americans’ views toward the federal system.

We used the responses to the items in Table 1 to calculate an additive index of public preferences for federalism. To calculate this index, we used the full four-point response options for each of the ten indicators, where larger values indicated increased support for state rather than national power. The items in Table 1 with the (RC) identifier were reverse coded to be consistent with this interpretation. We then rescaled the values of this measure so that they ranged between zero and one. Overall, the scale appears to produce an internally consistent and reliable measure of federalism preferences, as the Cronbach’s alpha is 0.72.Footnote 8

Figure 1 displays the distribution of respondents’ federalism preferences.Footnote 9 The mean score is nearly in the center of the range, reflecting the mixed aggregate patterns shown in Table 1. Moreover, relatively few respondents have scores at the extreme ends of the range, suggesting that most Americans do not hold absolutist views about state versus national control of government.Footnote 10

Measurement Validation

We validate our federalism measure by studying its relationship with attitudes toward policy devolution. To the extent Americans possess coherent preferences for federal arrangements, we would expect that their general views toward federalism would be associated with their attitudes about which level of government should exert control over specific policy areas.Footnote 11

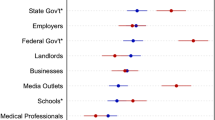

We measured preferences for policy devolution by asking respondents whether local, state, or federal government ought to have primary control over nine different issue areas: education, roads and infrastructure, economic affairs, foreign affairs, environmental policy, health policy, social welfare, law enforcement, and criminal justice.Footnote 12 A respondent has a preference for devolution if they believe that policy control ought to be at the state or local level rather than at the federal level. Overall, we find that preferences for devolution vary across issue areas. For example, nearly three-quarters of respondents (74 percent) preferred devolution to address roads and infrastructure while less than half of respondents preferred devolution in the areas of foreign affairs and defense (20 percent), environmental policy (39 percent), and economic affairs (46 percent). For the most part, partisan differences in preferences for devolution were relatively small in magnitude, although Republicans and Democrats differed by four to twelve percentage points in support for devolution on education, roads and infrastructure, health policy and social welfare.Footnote 13

We estimate linear probability models to predict preferences for devolution across each issue area. Table 2 presents the results, where the dependent variable is an indicator for whether a respondent prefers devolution in the relevant policy domain. Our main independent variable is respondents’ federalism scores from Fig. 1. Given how we coded responses to the federalism battery, we expect a positive relationship between our battery and each of the dependent variables, which would indicate that individuals who report abstract preferences for state power relative to national power are more likely to support policy devolution. To distinguish whether federalism preferences reflect individuals’ general ideological orientations, we control for respondents’ ideological self-placements on a five-point scale from “very conservative” (1) to “very liberal” (5). We created indicators for respondents who identified as Republicans or Democrats, treating leaners as partisans. Thus, independents are the omitted category. We also include several demographic controls for income (scaled to range between 0 and 1), race, Hispanic origin, individuals with college degrees, and gender. Because political culture and context can vary across states and may affect how respondents evaluate national versus state power, we include state fixed effects in our models. Standard errors are clustered by state.

We find that respondents with greater preferences for federalism as measured by our battery are more likely to prefer policy devolution to the state or local level. This relationship is positively signed in eight of the nine issue areas and is statistically distinguishable from zero in seven of them.Footnote 14 Interestingly, the magnitude of the relationship varies somewhat across policy areas. Just as preferences for devolution may vary across policy areas (Schneider et al., 2011), so too might the relationship between diffuse attitudes toward federalism and devolution in a particular policy domain. And, as the final column of Table 2 shows, this relationship holds when calculating each respondents’ average preferences for devolution across all issues, where the coefficient for federalism preferences is again positive and statistically significant. These results lend support for the validity of our measure of federalism preferences.

Predictors of Preferences for Federalism

Using our measure of preferences for federalism, we now investigate how these attitudes are associated with individual characteristics and political context. We begin by evaluating how partisanship and ideology are associated with respondents’ preferences for federalism. We include indicators for respondents who identified as Republicans and Democrats along with respondents’ five-point ideological self-placements, where larger values indicate individuals who reported more liberal orientations. As before, we include demographic controls and cluster standard errors on state.

Table 3 presents our results. The results in column (1) provide little evidence that partisanship is systematically associated with preferences for federalism. The coefficients for the indicators for both partisan indicators are small in magnitude and neither is statistically distinguishable from zero. However, we do find evidence of a link between ideological self-placements and views toward federalism. The coefficient for Ideology is negative and statistically significant, indicating that individuals with more liberal orientations have lower scores on our federalism battery. Respondents with more conservative ideologies are more supportive of state power vis-à-vis national power compared with individuals with more liberal ideological beliefs. These results provide support for the claim that attitudes toward federalism are associated with individuals’ underlying ideological orientations.

Column (2) reports results when our model includes state fixed effects. In this specification, the coefficients for partisanship reflect difference within states rather than cross-sectionally within the entire sample. We find similar results as in column (1). The model provides evidence of a link between ideology and attitudes toward federalism but no evidence that Republicans and Democrats have systematically different views about federalism.Footnote 15

State Political Context and Preferences for Federalism

While an individual’s partisan affiliation may not be predictive of her attitude toward federalism, these beliefs may vary with state political context. For example, individuals who share the partisanship of state government officials might be more supportive of those officials’ policy agendas and express greater trust in state government more generally. In turn, individuals whose state officials share their partisanship may support greater power for states relative to the national government. Likewise, individuals who have more favorable evaluations of their state government may also express greater support for state power relative to federal power. We test these hypotheses with two sets of measures. In the first, we create indicators for Same-party governor and Opposite-party governor. The former measure takes a value of 1 if the respondent and her state’s governor are from the same party, and zero otherwise. The latter measure takes a value of 1 if the respondent and her governor are from opposite parties, and zero otherwise. Thus, Independents have values of zero for both indicators.

For the second measure, we use Gubernatorial approval. This variable indexes respondents’ approval ratings of their state’s governor, which were measured on five-point scales from “strongly disapprove” to “strongly approve.” We rescaled this measure to range between zero and one, where larger values indicate respondents who evaluated their governor more favorably. In all our models, we again include controls for self-identified ideology and demographic characteristics, as well as state fixed effects.Footnote 16

The first column of Table 4 shows the result of a model that includes indicators for respondents’ partisan alignments with their state’s governor. The coefficient for Same-party governor is positive but small in magnitude and is not statistically significant. Likewise, the coefficient for Opposite-party governor is positive, but it too is small in magnitude and statistically indistinguishable from zero. Column (2) shows the results when accounting for Gubernatorial approval. The coefficient for this covariate is positive and statistically significant, indicating that increased approval of one’s governor is associated with greater support for state power relative to national power. Column (3) shows results when jointly accounting for partisan alignment with the government and respondents’ approval of the governor relative to the president. We continue to find little evidence that partisan alignment with state government is associated with attitudes toward federalism. We also continue to find that Gubernatorial approval is positive and statistically distinguishable from zero. However, the magnitude of its relationship with respondents’ federalism preferences is relatively small. A one-unit change in Gubernatorial approval—that is, from “strongly disapprove” to “strongly approve”—is associated with an increase in federalism preferences equivalent to about one-quarter of a standard deviation.Footnote 17 Overall, we find little evidence that attitudes about federalism are simply a reflection of an individual’s partisan context.Footnote 18 This finding contrasts with results presented in Dinan and Heckelman (2020), who show that Democrats and Republicans differ systematically in their preferences for devolution. They further show that these preferences are sensitive to changes in political context, particularly among Democrats. While we find in Table C.1 that preferences for policy devolution vary somewhat with partisanship, we find no evidence in Table 3 that individuals’ partisanship is associated with more general preferences for the allocation of power across state and national government. Furthermore, Table 4 provides no evidence that individuals’ partisan contexts are associated with their views toward federalism. Instead, we find relatively consistent evidence that respondents’ ideological orientations are connected with their views toward federalism, suggesting that these preferences are rooted in more deeply-seated political values. Finally, the results presented above provide some evidence that greater satisfaction with state relative to national government is associated with increased support for state power, though the findings are modest in magnitude.

Performance Evaluations and Attitudes toward Federalism

In a final set of analyses, we consider how individuals’ performance evaluations of state and national government are associated with their attitudes toward federalism. In particular, we consider whether individuals who report greater satisfaction with their state government’s performance relative to national government express stronger preferences for state power. While Gehring (2021) presents evidence for this hypothesis in a cross-national setting, to our knowledge no studies investigate this possibility in the context of the United States. We address this question in the context of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Our survey was fielded several months into the pandemic’s spread in the United States. Therefore, every respondent was “treated” by the country’s national policy response to the pandemic, while responses varied significantly across state lines as governors and other policymakers adopted divergent means of addressing the crisis.Footnote 19 State-level variation in pandemic response thus is likely to generate variation in respondents’ approval of their governors. We asked respondents four questions to evaluate their state’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic along fivepoint scales, where larger values indicate greater approval or agreement. In addition to a question that asked about respondents’ general approval of how state officials have handled the pandemic on a five-point scale, they were asked each of the followingFootnote 20:

-

My state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was aggressive. (strongly disagree [1]/strongly agree [5])

-

My state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was appropriate. (strongly disagree [1]/strongly agree [5])

-

Compared to other states, how would you rate the performance of your state government’s response to coronavirus and COVID-19? (much worse [1]/much better [5])

We created a measure of State job performance by averaging the five-point responses to each question.Footnote 21 We then rescaled the measure to range from zero and one, where larger values indicate higher performance ratings of state government. We estimate regression models that include this composite measure as a predictors of attitudes toward federalism. We again include demographic and political controls, estimate models with state fixed effects, and cluster standard errors on state.

Table 5 shows these results. The model reported in column (1) shows that the coefficient for State job performance is positive and statistically significant, indicating that individuals who evaluated their state’s pandemic response more approvingly expressed stronger preferences for state power. Column (2) includes state fixed effects, so that the coefficients now compare among respondents living in the same state. We again find that the coefficient is positive and statistically significant, indicating that individuals in a given state who were more approving of their state’s response to the pandemic expressed greater support for state power.

The results in Table 5 provide evidence that Americans’ attitudes toward federalism are at least partially responsive to their performance evaluations of state government. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals who perceived their state as responding more effectively supported more authority for state government relative to national government.

We acknowledge the challenges in interpreting our ordinary least squares estimates as causal estimates as they are likely to be biased. In particular, individuals’ evaluations of state governmental performance could be endogenous to their federalism preferences. To address this possibility, and to further explore the relationship between state outcomes and respondents’ evaluations, we instrument evaluations of state job performance with the percentage of individuals in a given respondent’s county confirmed with COVID-19 at the time of the survey. The intuition for this specification is that local experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to affect beliefs about federalism only through their impact on respondents’ evaluations of state government.

The results of the instrumental variables analysis and further discussion are included in Appendix Section D.1. Our two stage least squares estimates are consistent with those presented in Table 5. Local experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic are positively associated with state government evaluations in the first stage model; moreover, the second stage model shows a statistically significant relationship with federalism preferences. While we do not wish to overinterpret the estimates because our instrument is relatively weak, the findings provide support for a causal link between state government performance and preferences for the allocation of state power.

Overall, our results suggest that evaluations of federalism appear to reflect both ideological commitments and evaluations of government performance. Moreover, we find suggestive evidence that these evaluations of government performance are not completely uncoupled from real policy outcomes, implying that preferences for state power are in part shaped by sub-national government’s agendas and actions.

Conclusion

Conflicts between state and national authority are omnipresent in policy debates in American politics. At the elite level, these debates often reflect partisan politics. For instance, though Democratic officials tend to advocate for more centralized, national authority, policy disagreements with Republican figures in national government are sometimes accompanied of the assertion of local prerogative by Democratic officials serving in local positions.Footnote 22 Yet, at least among elites, these debates often invoke more abstract principles related to the importance of local control. Are these factors reflected in Americans’ views about federalism? Addressing this question is important for characterizing how Americans view the distribution of power and understanding how elite debates resonate with the American public.

We present a new measure of public preferences for federalism. Our measurement approach follows Easton (1965, 1975), who distinguishes evaluations of political authorities from evaluations of political systems. The components of our federalism battery were designed to measure the latter quantity. Thus, while existing research focuses largely on performance evaluations and approval ratings of local, state, and national government, our measure focuses attention on respondents’ core beliefs about the distribution of authority in a federal system. This approach allows us to evaluate the presence and correlates of attitudes about national and state power that may structure evaluations of federalism in individual policy domains (see, e.g., Schneider et al., 2011).

Using our measure of diffuse attitudes about the distribution of power across national and state governments, we uncover several new findings about the predictors of attitudes toward federalism. First, we show that neither individuals’ partisanship nor their partisan alignment with governing officials predicts support for state power vis-`a-vis national power. Second, these beliefs are more strongly and reliably associated with ideological orientations, where individuals with more conservative self-reported ideologies express greater support for state rather than national control. This evidence may suggest that federalism preferences are more deeply-rooted in core political values than they are in more ephemeral partisan debates. Third, we provided evidence that preferences toward federalism may reflect respondents’ evaluations of the performance of state government. As individuals believe that state authorities more effectively address contemporary problems, they express greater support for state power.

Our findings provide a starting point for additional research about the political significance of Americans’ attitudes about federalism. We invite further research to employ and revise our measure of preferences for federalism and to study the conditions under which they are relevant for understanding political debates. Indeed, our analysis did not probe all relevant factors that may structure beliefs about federalism and the distribution of political power. For example, prior research has highlighted the role of regional equity in evaluations of federalism (Kincaid & Cole, 2016). To the degree that the federal government is perceived to treat states fairly in distributing resources, the public may be more accepting of national power than if the federal government is perceived to allocate resources in a more biased manner. We also did not account for the relationship between state and local government. Individuals may also have preferences for the relationship between local and state power, and these relationships may also vary with the relative performance of local governments. Exploring these possibilities can enrich our knowledge about how the public evaluates the distribution of authority across multiple levels of government.

Of course, our analyses have important limitations. Respondents’ attributes and political contexts were not randomly assigned, and thus our findings are correlational in nature. Additional research is needed to study how these factors are causally related to views about federalism. It would also be useful to evaluate temporal variation in the attitudes reported in our study. Our survey was conducted during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, when the relationship between state and national government may have been especially salient. Understanding whether attitudes toward federalism are stable at the aggregate and individual levels would shed additional light on the nature of these beliefs. Finally, our research leaves unanswered the question of whether and how these attitudes might structure how individuals evaluate specific politics and government actions. For example, do individuals view policies differently depending on which level of government implements them, in ways that vary with their more abstract beliefs about federalism? This is an important agenda for future scholarship.

Data Availability

All data will be made publicly available upon acceptance of the manuscript for publication.

Code Availability

Data and code are publicly available at the Political Behavior Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8JVXOS).

Notes

For a contrasting view, see Friedman (2010).

See also Roeder (1994).

Unweighted results for the analyses presented below are shown in Appendix A. While the weights occasionally have minor implications for the descriptive patterns shown in Table 1 and the magnitudes of the regression coefficients presented below, none of our substantive inferences depend on applying the survey weights.

Of course, this is not the only intergovernmental relationship in federal systems. Future work could also incorporate preferences for local control in addition to national and state power, or evaluate attitudes on the relationship between state and local government.

The absence of a neutral and/or “don’t know” option differs from Schneider and Jacoby (2003). By forcing respondents to provide an answer even if they are genuinely ambivalent or unsure, we may risk biasing or inducing measurement error in our assessments of preferences toward federalism. While we cannot entirely rule out this possibility, our validation exercise below provides evidence that responses to the federalism battery are correlated with other attitudes toward federalism in ways that suggest the validity of the measure.

The results for these three questions are generally similar (though not identical) to those reported in Schneider and Jacoby (2003), who use a sample from South Carolina and a five-point scale with a neutral middle option.

The secession figure is somewhat higher than what some previous polls have found. For instance, 30 percent of respondents in a poll conducted by CBS in 2013 supported allowing a state to secede if its citizens voted to do so (CBS News, 2013) and 25 percent of Americans supported a similar item in a 2010 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center. One potential explanation for the relatively higher support for our secession item is that it asks about the right to secede as opposed to being in favor of secession. It is also possible that our findings reflected the particular context during which our survey was conducted. For example, a 2021 poll conducted by the UVA Center for Politics found than 40 to 50 percent of Americans favored secession (see https://centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/articles/new-initiative-explores-deeppersistent-divides-between-biden-and-trump-voters/. Evaluating potential change over time is an important opportunity for future research.

Factor analysis indicated that the items loaded on a single factor, which was the modal result across a number of factor retention criteria. Table B.1 shows the loadings for each item on a single factor. All items load fairly strongly with the exception of the item asking respondents whether the national government should do more to solve pressing problems in society. Table B.1 also shows loadings for models with two and three retained factors. We do see some evidence that the three items assessing the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and superiority of ideas of state government may comprise a distinctive factor. However, because we do not have strong theoretical expectations about the multidimensional nature of attitudes toward federalism, we are reluctant to interpret these patterns more definitively. Due to the variation in the item loadings for the single factor model, we replicate all analyses below using the factor loadings to create a measure of federalism preferences that ranges between zero and one. These results are shown in Appendix B. This alternative measurement strategy does not change our substantive inferences.

Figure B.1 in the Appendix shows the distribution of federalism preferences when they are calculated using the factor loadings. This measure is correlated with the additive index at .93.

Figure C.1 in the Appendix shows how preferences for federalism vary across states. We make these comparisons more tentatively since our sample is not designed to be representative at the state level and many states have relatively small samples. Interestingly, though, the figure suggests that state level preferences toward federalism are not neatly distinguished on the basis of partisan control of the governorship (though in some cases gubernatorial partisanship is not neatly aligned with the public’s or the legislature’s preferences).

As Thompson and Elling (1999) show, the public may prefer for multiple levels of government to be involved in a given policy area. For the purposes of validating our measure of preferences for national versus state power, however, we focus on evaluating whether our measure of preferences for national power map onto an individual’s preferences for primary control over specific policy domains.

We show an image of the survey instrument in Figure C.2.

Descriptive statistics for the aggregate sample and by party are shown in Table C.1.

The coefficient for federalism preferences is negatively signed for the foreign affairs policy domain, though it is small in magnitude and not distinguishable from zero. Note, too, that preferences for devolution were weakest in this issue area. We find similar patterns when using the factor score based measure rather than the additive index, as the coefficient for federalism preferences is positively signed in eight of the nine issue areas and statistically distinguishable from zero in five. The composition measure is also positive and statistically significant. See Table B.2.

When using the factor score measure of federalism preferences, we find positive, and generally statistically significant, coefficients for the partisan indicators. These patterns suggest that both Democrats and Republicans have more favorable attitudes toward federalism than political Independents, but they also support the finding from Table 3 that there are no major differences in views toward federalism between members of different parties. See Table B.3.

We include controls for partisanship only in the models that do not include Same-party governor and Opposite-party governor, since these variables are perfectly collinear with respondent partisanship.

The standard deviation of the federalism preferences measure is 0.14.

We provide additional evidence for this claim in two additional analyses. First, when using the factor score measure of federalism, we continue to find little difference in views about federalism based on whether an individual is a copartisan or counterpartisan of the governor, though we do find a positive association between gubernatorial approval and federalism preferences. See Table B.4. Second, we used an alternative measure to characterize individuals’ partisan alignment with state government. Rather than construct a measure based solely on the governor’s partisanship, we based it on partisan control of the state legislature as well as the governorship. This measure takes a value of one if a respondent shared the partisanship of the party that controlled the state legislature and the governorship, a value of 0.5 in states with divided party control, and a value of zero if both branches are controlled by the party opposite the respondent’s. We omitted independents for the purposes of this analysis. Using this measure, the coefficient estimate for partisan alignment is extremely small in magnitude and indistinguishable from zero. See Table C.2.

Policy responses also varied by locality, though our analysis focuses on state-level variation.

A neutral middle option was available in each set of response options. The distribution of responses to each question is shown in Table C.3 in the Appendix.

The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for these four items is .82. Factor analysis indicates that these items load on a single dimension.

See, e.g., Dara Lind, March 8, 2018, “Sanctuary cities, explained,” Vox; available at https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/3/8/17091984/sanctuary-cities-city-stateillegal-immigration-sessions.

References

Aidt, T. S., & Dutta, J. (2017). Fiscal federalism and electoral accountability. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 19(1), 38–58.

Arceneaux, K. (2005). Does federalism weaken democratic representation in the United States? Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 35(2), 297–311.

Becher, M., & Brouard, S. (2022). Executive accountability beyond outcomes: Experimental evidence on public evaluations of powerful prime ministers. American Journal of Political Science, 66(1), 106–122.

Beienburg, S. (2018). Neither nullification nor nationalism: The battle for the states’ rights middle groundduring prohibition. American Political Thought, 7, 271–303.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. University of Chicago Press.

Carpini, M. X. D., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. Yale University Press.

CBS News. (2013). CBS News Poll: October 2013

Chemerinsky, E., Forman, J., Hopper, A., & Kamin, S. (2015). Cooperative federalism and marijuana regulation. UCLA Law Review, 62, 74–122.

Chhibber, P., & Kollman, K. (2004). The formation of national party systems: Federalism and party competition in Canada, Great Britain, India, and the United States. Princeton University Press.

Cole, R. L., Kincaid, J., & Rodriguez, A. (2004). Public opinion on federalism and federal political culture in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, 2004. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 34(3), 201–221.

Dahl, R. (2002). How democratic is the constitution? Yale University Press.

Dinan, J., & Heckelman, J. C. (2020). Stability and contingency in federalism preferences. Public Administration Review, 80(2), 234–243.

Doherty, D., & Wolak, J. (2012). When do the ends justify the means? Evaluating procedural fairness. Political Behavior, 34, 301–323.

Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. Wiley.

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science, 5, 435–457.

Fitzgerald, M. R., McCabe, A. S., & Folz, D. H. (1988). Federalism and the environment: The view from the states. State and Local Government Review, 20(3), 98–104.

Friedman, B. (2010). The will of the people: How public opinion has influenced the supreme court and shaped the meaning of the constitution. Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Gehring, K. (2021). Overcoming history through exit or integration: Deep-rooted sources of support for the European Union. American Political Science Review, 115(1), 199–217.

Gerken, H. K. (2017). Federalism 3.0. California Law Review, 105, 1695–1724.

Gibson, J. L. (1989). Understandings of justice: Institutional legitimacy, procedural justice, and political tolerance. Law & Society Review, 23(3), 469–496.

Goelzhauser, G., & Rose, S. (2017). The state of American federalism, 2016–2017: Policy reversals and partisan perspectives on intergovernmental relations. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 47(3), 285–313.

Goldsmith, J. L. (1997). Federal courts, foreign affairs, and federalism. Virginia Law Review, 83(8), 1617–1715.

Green, J. C., & Guth, J. L. (1989). The missing link: Political activisits and support for school prayer. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53, 41–57.

Gruber, J., & Sommers, B. D. (2020). Fiscal federalism and the budget impacts of the affordable care act’s medicaid expansion. NBER Working Paper No. 26862; Retrieved December 6, 2020, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w26862

Grumbach, J. M., & Michener, J. (2022). American federalism, political inequality, and democratic erosion. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 699(1), 143–155.

Haffajee, R. L., & Mello, M. (2020). Thinking globally, acting locally—The U.S. response to covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(22), e75.

Hetherington, M. J., & Nugent, J. D. (2001). Explaining public support for devolution: The role of political trust. In J. R. Hibbing & E. Theiss-Morse (Eds.), What is it about government that Americans dislike? (pp. 134–156). Cambridge University Press.

Hibbing, J. R., & Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how government should work. Cambridge University Press.

Kam, C. D., & Mikos, R. A. (2007). Do citizens care about federalism? An experimental test. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 4(3), 589–624.

Kincaid, J. (2017). Introduction: The trump interlude and the states of American federalism. State and Local Government Review, 49(3), 156–169.

Kincaid, J., & Cole, R. L. (2016). Citizen evaluations of federalism and the importance of trust in the federation government for opinions on regional equity and subordination in four countries. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 46(1), 51–76.

Kolcak, B., & McCabe, K. T. (2021). Federalism at a Partisan’s Convenience: Public opinion on federal intervention in 2020 election policy. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, and Parties, 31(1), 167–179.

Lund, N. (2003). Federalism and the constitutional right to keep and bear arms. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 33(3), 63–81.

Melder, F. E. (1939). Trade barriers and states’ rights. American Bar Association Journal, 25(4), 209–307.

Mettler, S. (2000). States’ rights, women’s obligations. Women & Politics, 21(1), 1–34.

Mooney, C. Z. (2000). The decline of federalism and the rise of morality-policy conflict in the United States. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 30(1–2), 171–188.

Morisi, D., Jost, J. T., & Singh, V. (2019). An asymmetrical ‘president-in-power’ effect. American Political Science Review, 113(2), 614–620.

Myerson, R. B. (2006). Federalism and incentives for success in a democracy. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 1, 3–23.

Nemerever, Z. (2021). Contentious federalism: Sherifs, state legislatures, and political violence in the American West. Political Behavior, 43, 247–270.

Ordeshook, P. C., & Shvetsova, O. (1995). If Hamilton and Madison were merely lucky, what hope is there for Russian federalism? Constitutional Political Economy, 6, 107–126.

Pew Research Center. (2018). American trends panel, wave 31. Conducted January 29–February 13. Retrieved December 8, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/dataset/american-trends-panel-wave-31/

Phillips, K. P. (1969). The emerging republican majority. Anchor Books, Doubleday and Company.

Reeves, A., & Rogowski, J. C. (2016). Unilateral powers, public opinion, and the presidency. Journal of Politics, 78(1), 137–151.

Reeves, A., & Rogowski, J. C. (2022). No blank check: The origins and consequences of public antipathy towards presidential power. Cambridge University Press.

Reeves, M. M., & Glendening, P. N. (1976). Areal federalism and public opinion. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 6(2), 135–167.

Riker, W. H. (1964). Federalism: Origin, operation, significance. Little, Brown.

Rodriguez, C. (2017). Enforcement, integration, and the future of immigration federalism. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 5(2), 509–540.

Roeder, P. W. (1994). Public opinion and policy leadership in the American States. University of Alabama Press.

Sances, M. W. (2017). Attribution errors in federalist systems: When voters punish the president for local tax increases. Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1286–1301.

Schneider, S. K., & Jacoby, W. G. (2003). Public attitudes toward the policy responsibilities of the national and state governments: Evidence from South Carolina. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 3(3), 246–269.

Schneider, S. K., Jacoby, W. G., & Lewis, D. C. (2011). Public opinion toward intergovernmental policy responsibilities. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 41(1), 1–30.

Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2010). Degrees of democracy: Politics, public opinion, and policy. Cambridge University Press.

Stevens, D. (2002). Public opinion and public policy: The case of Kennedy and civil rights. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 32(1), 111–136.

Stratford, M. (2018). Trump endorses states’ rights–but only when he agrees with the state. Politico. https://www.politico.com/story/2018/04/02/trump-states-rights-education-sanctuary-drilling-492784

Thompson, L., & Elling, R. (1999). Let them eat marblecake: The preferences of Michigan citizens for devolution and intergovernmental service-provision. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 29(1), 139–153.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 399–457.

Tushnet, M. V. (2005). A court divided: The rehnquist court and the future of constitutional law. W. W. Norton & Company.

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, & Committee on Government Reform and Oversight. (1995). The federalism debate: Why doesn’t washington trust the states? Hearing before the subcommittee on human resources and intergovernmental relations of the committee on government reform and oversight. Testimony to the Subcommittee on Human Resources and Intergovernmental Relations Committee on the Government Reform and Oversight, United States House of Representatives. July 20

Weisman, J. (2022). Spurred by the supreme court, a nation divides along a red-blue axis. New York Times.

Wlezien, C., & Soroka, S. N. (2011). Federalism and public responsiveness to policy. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 41(1), 31–52.

Wolak, J. (2016). Core values and partisan thinking about devolution. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 46(4), 463–485.

Funding

Funding was provided to Rogowski by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HR and JCR jointly designed the survey instrument. HR programmed the instrument into Qualtrics; JCR submitted the human subjects application. HR performed the analyses for and reported the empirical estimates in the paper; JCR wrote the text for the other portions of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Harvard University Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (#IRB20-0633).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Data and code to reproduce the results presented in this article are deposited at the Political Behavior Dataverse and are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8JVXOS. We thank three anonymous reviewers and the Editor for helpful comments and suggestions. Harvard University provided financial support.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rendleman, H., Rogowski, J.C. Americans’ Attitudes Toward Federalism. Polit Behav 46, 111–134 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09820-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09820-3