Abstract

The ability of women in office to inspire other women to enter politics can be an important process in undoing longstanding gender gaps in political representation. Previous research on this potential role model effect of female officeholders finds mixed results in terms of female candidacies across a wide range of contexts. Explanations for these mixed findings include that positive effects are conditional on the nature of women’s incorporation in a given context, and also suggest female incumbents can lower the perceived need/utility of more women running. I take a wider view and test for role model effects across different levels of the candidate emergence process. In doing so, I put a spotlight on a potentially pivotal variable: the role of parties and their candidate selection processes in moderating role model effects. Through a case study of Mexico, I find evidence of engagement effects among women in the mass public as well as women seeking party nominations, but no evidence for role model effects at the candidate-level (either within or across districts) in congressional elections. Using data on the candidate nomination processes of one major political party, I find evidence that party decisions in candidate selection methods attenuate possible role model effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Replication materials are available via the Political Behavior Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LGWQB5.

As Lawless and Fox (2010) argue, the deficit in women’s representation is due in larger part to deficits in the number of women candidates than deficits in electoral performance compared to men. Langston and Aparicio (2011) find similar patterns in the case of Mexican legislative elections, the focus of this paper.

To further explore the potential for contagion effects, I provide a cursory analysis of Mexican legislative candidacies discussed in the online appendix and summarized in Table A12 of the online appendix. I find that contagion effects are not likely working in tandem with role model effects and in fact may work in the opposite direction.

Senior project personnel for the Mexico 2012 Panel Study include (in alphabetical order): Jorge Domínguez, Kenneth Greene, Chappell Lawson, and Alejandro Moreno. Funding for the study was provided by the Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinión Pública de la Cámara de Diputados (CESOP) and the Secretaría de Gobernación; fieldwork was conducted by DATA OPM, under the direction of Pablo Parás.

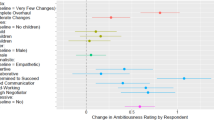

An alternative strategy would be to pool both men and women together and include an interaction term between gender and the indicator for a woman winning in the district. I opt for sub-setting the data in this way, which is equivalent to a fully interacted model. However, I report the results of these pooled analyses in Table A2 and Fig. A1 of the online appendix.

Documents from the party’s Electoral Organizing Committee are available at http://www.pan.org.mx/estrados-electronicos-coe-archivo/.

I do not have data on districts where the party simply designated a candidate, since there is no self-nomination by pre-candidates in those cases.

Economically active persons are defined as those who work, had a job but are not currently working, or were seeking work in the reference week.

It should be noted that given Mexico’s mixed electoral system, which distributes votes in the proportional representation (PR) tier based on votes in the single member districts (SMDs), parties and coalitions have an incentive to and do field candidates in every congressional district so as to maximize the number of votes for the larger PR tier districts.

The models in Fig. 2 are each OLS regressions of a measure of political engagement on an indicator variable for a woman winning in the legislative district, a lagged dependent variable, pre-electoral political preferences, and demographic variables, with robust standard errors. Table A1 in the online appendix summarizes the estimates and fit statistics for these models. R-squared for the models ranges from .1 to .15.

Table A3 in the online appendix summarizes the estimates and fit statistics for this model as well as the corresponding model for men.

The results for the male subsample of the interaction analysis are plotted in Fig. A2 of the online appendix.

Along with the results presented here, I also conducted an interactive analysis that substituted political information with copartisanship with the winning candidate as the moderator of interest. To the extent that role model effects are present among the mass public, one would expect they are strongest among copartisans of the winner. Indeed, I do find that the role model effect is stronger among copartisans with the winner. However, there are very few copartisans in the second wave of the panel (among women, 86 weak copartisans and 81 strong copartisans in total). I exercise caution in drawing strong conclusions from such observations. Results for this analysis can be found in Table A4 and Fig. A3 of the online appendix.

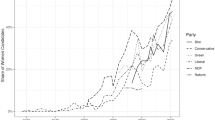

The reason the two models have a differing number of observations is because the PAN reserved some primaries for only female pre-candidates in 2015. The results here are robust to including an indicator for this reserved primary system in the model of the number of female pre-candidates. Those results are summarized in Table A6 of the online appendix.

Holding the share of neighboring women winners (t-1) at its mean value and the safe PAN indicator at its mode of zero.

I also conducted a similar analysis to the one in Table 1 that isolates for simply partisan effects. Rather than any woman winning in the district or neighboring districts, that analysis includes whether a PANista woman won in 2012 and whether a PANista woman won in a neighboring district in 2012. If partisan motivations are driving role model effects among aspirants, I should see stronger effects in this model. I find null results for both partisan role model variables. Results are reported in Table A7 of the online appendix. This indicates that it is not only PANista female winners that motivate PANista aspirants.

One possibility is that any effects of candidacies from female officeholders is entirely within-parties, rather across all parties as tested here. To investigate this possibility I conduct additional analysis only for the PAN, which is a useful case since it is the only major party in this period that did not engage in electoral alliances with other parties. I substitute the main variables of interest with an indicator of whether a PANista woman won the district and the percent of PANista women among the neighboring winners. The dependent variable has been changed to an indicator of whether the PAN nominated a woman in that election. The results, reported in Table A10 in the online appendix, show that there are no role model effects in this strictly partisan model. In fact, the effect for previous female PANista winner in the district is negative and significant at the .05 level.

Count models with the number of female candidates (rather than the share) as the dependent variable and controlling for the total number of candidates produce similar results.

The breakdown of how frequently each method was used across the 300 single member districts is as follows: Closed primary - 138, designation - 76, woman-reserved primary - 82, open primary - 4.

The share of women nominees to come out of each selection method was 18% (closed primary), 60.5% (designation), 94% (closed primary reserved for women pre-candidates), and 50% (open primary). Although women seem to perform better than prior research would expect in open primaries, this selection method was only used in 4 districts in 2015, so one should be cautious to conclude that PANista women fare well in open legislative primaries.

Table A11 in online appendix summarizes the estimates for the model used to plot Fig. 5.

Figure A4 in the online appendix plots the distribution of the PAN’s electoral performance in 2012 across the single member districts. One should note that given Mexico’s multiparty system, parties rarely receive more than 50% of a district’s votes. The first-place party in a district typically wins with a plurality considerably below the 50% mark.

References

Atkeson, L. R. (2003). Not all cues are created equal: The conditional impact of female candidates on political engagement. Journal of Politics, 65(4), 1040–1061.

Barnes, T. D., & Burchard, S. M. (2012). “Engendering" politics: The impact of descriptive representation on women’s political engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 46(7), 767–790.

Beaman, L., Chattopadhyay, R., Duflo, E., Pande, R., & Topalova, P. (2009). Powerful women: Does exposure reduce bias? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4), 1497–1540.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647.

Bhalotra, S., Clots-Figueras, I., & Iyer, L. (2018). Pathbreakers? Women’s electoral success and future political participation. Economic Journal, 128(613), 1844–1878.

Bhavnani, R. R. (2009). Do electoral quotas work after they are withdrawn? Evidence from a natural experiment in India. American Political Science Review, 103(1), 23–35.

Bjarnegård, E., & Zetterberg, P. (2016). Political parties and gender quota implementation: The role of bureaucratized candidate selection procedures. Comparative Politics, 48(3), 393–411.

Broockman, D. E. (2014). Do female politicians empower women to vote or run for office? A regression discontinuity approach. Electoral Studies, 34, 190–204.

Bruhn, K., & Wuhs, S. T. (2016). Competition, decentralization, and candidate selection in Mexico. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(7), 819–836.

Campbell, D. E., & Wolbrecht, C. (2006). See Jane Run: Women politicians as role models for adolescents. Journal of Politics, 68(2), 233–247.

Caul, M. (1999). Women’s representation in parliament: The role of political parties. Party Politics, 5(1), 79–98.

Caul, M. (2001). Political parties and the adoption of candidate gender quotas: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Politics, 63(4), 1214–1229.

Clayton, A. (2015). Women’s political engagement under quota-mandated female representation; evidence from a randomized policy experiment. Comparative Political Studies, 48(3), 333–369.

Clayton, A., O’Brien, D. Z., & Piscopo, J. M. (2019). All male panels? Representation and democratic legitimacy. American Journal of Political Science, 63(1), 113–129.

Desposato, S. W., & Norrander, B. (2009). The gender gap in Latin America: Contextual and individual influences on gender and political participation. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 141–162.

Dolan, J., Deckman, M. M., & Swers, M. L. (2007). Woman and politics: Paths to power and political influence. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Dolan, K. (2006). Symbolic mobilization? The impact of candidate sex in American elections. American Politics Research, 34(6), 687–704.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2014). Uncovering the origins of the gender gap in political ambition. American Political Science Review, 108(3), 499–519.

Funk, K. D., Hinojosa, M., & Piscopo, J. M. (2017). Still left behind: Gender, political parties, and Latin America’s pink tide. Social Politics, 24(4), 399–424.

Gauja, A., & Cross, W. (2015). Research note: The influence of party candidate selection methods on candidate diversity. Representation, 51(3), 287–298.

Gilardi, F. (2015). The temporary importance of role models for women’s political representation. American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 957–970.

Hinojosa, M. (2012). Selecting women, electing women: Political representation and candidate selection in Latin America. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Iversen, T., & Rosenbluth, F. (2008). Work and power: The connection between female labor force participation and female political representation. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 479–495.

Kanthak, K., & Woon, J. (2015). Women don’t run? Election aversion and candidate entry. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 595–612.

Kenny, M., & Verge, T. (2016). Opening up the black box: Gender and candidate selection in a new era. Government and Opposition, 51(3), 351–369.

Kerevel, Y. P., & Atkeson, L. R. (2017). Campaigns, descriptive representation, quotas and women’s political engagement in Mexico. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 5(3), 454–477.

Kunovich, S., & Paxton, P. (2005). Pathways to power: The role of political parties in women’s national political representation. American Journal of Sociology, 111(2), 505–552.

Langston, J. (2006). The changing party of the institutional revolution: Electoral competition and decentralized candidate selection. Party Politics, 12(3), 395–413.

Langston, J., & Aparicio, J. (2011). Gender quotas are not enough: How background experience and campaigning affect electoral outcomes. Mexico D.F.: C.d. I. y. D. Económicas.

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Politics of Presence? Congresswomen and Symbolic Representation. Political Research Quarterly, 57(1), 81–99.

Lawless, J. L., & Fox, R. L. (2010). It still takes a candidate: Why women don’t run for office. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Liu, S.-J.S. (2018). Are female political leaders role models? Lessons from Asia. Political Research Quarterly, 71(2), 255–269.

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent ‘yes. Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657.

Matland, R. E., & Studlar, D. T. (1996). The contagion of women candidates in single-member district and proportional representation electoral systems: Canada and Norway. Journal of Politics, 58(3), 707–733.

Norris, P., Vallance, E., & Lovenduski, J. (1992). Do candidates make a difference? Gender, race, ideology, and incumbency. Parliamentary Affairs, 45(4), 496–517.

Pereira, F. B. (2015). Electoral rules and aversive sexism: When does voter bias affect female candidates? Unpublished Manuscript.

Phillips, A. (1995). The politics of presence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Piscopo, J. M. (2016). When informality advantages women: Quota networks, electoral rules and candidate selection in Mexico. Government and opposition, 51(3), 487–512.

Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The concept of representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rahat, G., Hazan, R. Y., & Katz, R. S. (2008). Democracy and political parties: On the uneasy relationship between participation, competition and representation. Party Politics, 14(6), 663–683.

Reingold, B., & Harrell, J. (2010). The impact of descriptive representation on women’s political engagement: Does party matter? Political Research Quarterly, 63(2), 280–294.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Political parties and the recruitment of women to state legislatures. Journal of Politics, 64(3), 791–809.

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2005). The incumbency disadvantage and women’s election to legislative office. Electoral Studies, 24(2), 227–244.

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A., Malecki, M., & Crisp, B. F. (2010). Candidate gender and electoral success in single transferable vote systems. British Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 693–709.

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A., & Mishler, W. (2005). An integrated model of women’s representation. Journal of Politics, 67(2), 407–428.

Seltzer, R. A., Newman, J., & Leighton, M. V. (1997). Sex as a political variable. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Stockemer, D., & Byrne, M. (2012). Women’s representation around the world: The importance of women’s representation in the workforce. Parliamentary Affairs, 65(4), 802–821.

Thames, F. C., & Williams, M. S. (2013). Contagious representation: Women’s political representation in democracies around the world. New York: NYU Press.

Tripp, A., & Kang, A. (2008). The global impact of quotas: On the fast track to increased female legislative representation. Comparative Political Studies, 41(3), 338–361.

Wang, V., & Muriaas, R. L. (2019). Candidate selection and informal soft quotas for women: Gender imbalance in political recruitment in Zambia. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(2), 401–411.

Wolbrecht, C., & Campbell, D. E. (2007). Leading by example: Female members of parliament as political role models. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 921–939.

Wuhs, S. T. (2006). Democratization and the dynamics of candidate selection rule change in Mexico, 1991–2003. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 22(1), 33–56.

Wuhs, S. T. (2008). Savage democracy: Institutional change and party development in Mexico. University Park: Penn State Press.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the editor and anonymous reviewers of Political Behavior for their thoughtful comments. I also thank Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, Jonathan Hiskey, Joshua Clinton, Eric Guntermann and other participants at the 2018 MPSA conference for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castorena, O. Female Officeholders and Women’s Political Engagement: The Role of Parties. Polit Behav 45, 1609–1631 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09765-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09765-z