Abstract

Existing scholarship suggests that attitudes about the real or imagined beneficiaries or targets of public policies shape public opinion about those policies, with racial and ethnic stereotypes driving policy evaluations for many Americans. Despite the importance of these assumptions, we lack strong evidence about how and why people form such assumptions in the first place. In a pre-registered survey experiment, I demonstrate that elements of policy design (e.g., a work requirement) significantly affect the assumptions that individuals make about policy beneficiaries (their race and national origin). These assumptions shape individuals’ evaluations of the policy, conditional on existing attitudes (e.g., racial resentment). Importantly, existing attitudes do not condition the effects at the assumption stage: even those who profess not to believe in racial stereotypes about work ethic still assume that the absence of a work requirement makes a policy more likely to benefit blacks and immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data files and replication code are available in Stata format on the Political Behavior Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/X4EUKO.

Notes

There is some degree of endogeneity in this process, as perceptions of deservingness also guide the design of policy itself.

Of course, traditional cash welfare (now TANF) is no longer unconditional following the revisions of 1996, but this fact is apparently little-appreciated by the public (Soss and Schram 2007).

See Haselswerdt (2016) for all pre-registration details and the full pre-analysis plan. Note that all EGAP registrations have been migrated to the Open Science Framework website.

The wording of these hypotheses has been changed from the pre-analysis plan for clarity.

I return to this later, with reference to analyses displayed in Appendix 4.

Respondents who are familiar with the EITC may assume that the policy includes a work requirement even if they are in the “no work requirement” condition. This would bias the effect size downward, making this a tougher test of the hypotheses than it would otherwise be.

I include information about cost (based on the Joint Committee on Taxation’s budget estimate for the EITC) in order to fix this information across conditions. Since this study does not focus on fiscal attitudes, I want to avoid a situation in which respondents in one condition assume that the policy is more costly than those in other conditions.

These perception questions are deliberately placed after the approval question, to avoid explicitly priming considerations of race or immigration that would alter the respondent’s policy attitude.

There were only 17 such respondents (less than 1% of the sample). Excluding them from the analysis does not appreciably change the results.

This response option does not distinguish between illegal and legal immigrants. This was a deliberate choice, as the phrase “illegal immigrants” is a politically loaded term. Including it in the list may have undermined my effort to avoid aggressively priming issues of race or immigration.

Respondents were also asked whether they thought this policy was likely to be supported by Democrats, Republicans, both, or neither (see Appendix 1). I return to these questions in footnote 27.

Only three of these items were repeated on the 2016 ANES.

Analysis of the 2012 ANES finds that these five items scale well (α = .71).

Since the 2016 ANES included only three of the five immigration policy items, a three-item scale was used for that analysis. I used survey weights for all regressions using ANES data.

These control variables are part of my pre-registered design (Haselswerdt 2016). Simple regressions show that none of the attitudinal independent variables (symbolic racism, anti-immigration attitudes, ideology, and party identification) were affected by the experimental treatments.

Replication data and code can be accessed on the Political Behavior Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/X4EUKO. Workers on MTurk voluntarily select tasks and complete them in exchange for payment (45 cents in this case). 1865 unique workers accepted this task. Those that completed the survey on Survey Monkey were given a code to enter on MTurk to receive payment. Five were rejected for failing to enter the correct code. Another 61 were excluded due to missing data.

Appendix 3 provides more detail.

See Table 9.

See Appendix 2 for more information on what groups respondents identified as likely to benefit, including cross-tabulations.

Tables 11 and 12 in Appendix 4 substitute ideology and party identification for these group-specific variables in the interactions. Overall, no clear patterns emerge, though the negative coefficient of the conditional tax credit treatment was stronger for conservatives in the “immigrants only” model, and that of the conditional cash treatment was weaker for Republicans in the “blacks only” model.

This is somewhat in contrast to the findings of Ellis and Faricy (2019) on delivery mechanism and symbolic racism.

An additional multinomial analysis, displayed in Table 17, establishes that the effects of the conditional tax credit treatment on each “exclusive” group assumption are statistically significant even when considered in the same model.

Tables 18 and 19 and Figs. 5 and 6 in Appendix 5 display the results of alternative specifications that treat the assumptions that the minority groups will benefit as separate from the assumption that the majority groups will not benefit, with triple interactions between the assumptions and the attitudinal variables. Consistent with the main results, the negative interaction is strongest when the respondent assumes that the minority benefits to the exclusion of the majority. Tables 20 and 21 demonstrate that the interactive findings reported in the main results are robust to the inclusion of interaction terms of the assumptions with ideology and party identification.

One possible confounding factor here is assumptions about partisanship—it could be that the apparent interaction between assumptions about target groups and preexisting attitudes is just an artifact of assumptions about which of the major parties supports the proposal. Using questions included in the survey (see Appendix 1), I am able to rule out this possibility—see Table 22 in Appendix 5.

This scenario is a case of “Model 3” in Preacher et al. (2007) since the relationships between the mediator (group assumptions) and the dependent variable (policy approval) are conditioned by other variables (symbolic racism and anti-immigration attitudes). These analyses use “normal-theory” standard errors; bootstrapped standard errors for selected values are nearly identical. See Appendix 8 for details.

For nonwhite respondents, the interaction effect of the “immigrants only” assumption and anti-immigrant sentiment was actually larger than for white respondents (p = .08 for the triple interaction).

Note that there is some evidence of such effects in the multinomial logit results in Appendix 4.

References

Administration of Children and Families. (2019). Characteristi and financial circumstances of TANF recipients Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/characteristics-and-financial-circumstances-of-tanf-recipients-fiscal-year-2018.

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Nevitt Sanford, R. (1982). The authoritarian personality (Abridged ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.

Ashok, V. L., & Huber, G. A. (2019). Do means of program delivery and distributional consequences affect policy support? Experimental evidence about the sources of citizens’ policy opinions. Political Behavior.

Bergmann, M. (2011). IPFWEIGHT: Stata module to create adjustment weights for surveys. Statistical Software Components S457353, Boston College Department of Economics.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s mechanical turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Brown, H. E. (2013). Race, legality, and the social policy consequences of anti-immigration mobilization. American Sociological Review, 78(2), 290–314.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s mechanical turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Burgoon, B., Koster, F., & van Egmond, M. (2012). Support for redistribution and the paradox of immigration. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 288–304.

Callaghan, T., & Olson, A. (2017). Unearthing the Hidden Welfare State: Race, Political Attitudes, and Unforeseen Consequences. The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 2(1), 63–87.

Camorata, S. A. (2015). Welfare use by immigrant and native households: An analysis of medicaid, cash, food, and housing programs. Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder http://cis.org/sites/cis.org/files/camarota-welfare-final.pdf.

Carten, A. (2016). How racism has shaped welfare policy in America Since 1935. The Conversation column. http://theconversation.com/how-racism-has-shaped-welfare-policy-in-america-since-1935-63574.

Clifford, S., Jewell. R. D., & Waggoner, P. D. (2015). Are samples drawn from mechanical turk valid for research on political ideology?” Research & Politics 2(4).

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent (pp. 206–261). New York: Free Press.

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18.

Edelman, M. (1960). Symbols and political quiescence. The American Political Science Review, 54(3), 695–704.

Edelman, M. J. (1964). The symbolic uses of politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Eger, M. A. (2010). Even in Sweden: The effect of immigration on support for welfare state spending. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 203–217.

Ellis, C., & Faricy, C. (2019). Race, ’deservingness’, and social spending attitudes: The role of policy delivery mechanism. Political Behavior,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-09521-w.

Faricy, C., & Ellis, C. (2014). Public Attitudes toward social spending in the United States: The differences between direct spending and tax expenditures. Political Behavior, 36(1), 53–76.

Faricy, C. G. (2015). Welfare for the wealthy: Parties, social spending, and inequality in the US. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Federico, C. M. (2006). Race, education, and individualism revisited. The Journal of Politics, 68(3), 600–610.

Garand, J. C., Ping, X., & Davis, B. C. (2017). Immigration attitudes and support for the welfare state in the American mass public. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 146–162.

Gilens, M. (1996). ‘Race coding’ and white opposition to welfare. The American Political Science Review, 90(3), 593–604.

Gilens, M. (1999). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goren, P. (2003). Race, sophistication, and white opinion on government spending. Political Behavior, 25(3), 201–220.

Hahn, H., Aron, L., Lou, C., Pratt, E., & Okoli, A. (2017). Why does cash welfare depend on where you live? How and why state tanf programs vary. Urban Institute report,. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/why-does-cash-welfare-depend-where-you-live.

Haselswerdt, J. (2016). Policy design and public assumptions: A survey experiment on the submerged state. Evidence in Government and Politics/Open Science Framework Pre-Registration: osf.io/9t4qh.

Haselswerdt, J., & Bartels, B. L. (2015). Public opinion, policy tools, and the status quo: Evidence from a survey experiment. Political Research Quarterly, 68(3), 607–621.

Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253–283.

Horton, J. J., Rand, D. G., & Zeckhauser, R. J. (2011). The online laboratory: Conducting experiments in a real labor market. Experimental Economics, 14(3), 399–425.

Huber, G. A., & Paris, C. (2013). Assessing the programmatic equivalence assumption in question wording experiments: Understanding why Americans like assistance to the poor more than welfare. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77(1), 385–397.

Huddy, L., & Feldman, S. (2009). On assessing the political effects of racial prejudice. Annual Review of Political Science, 12(1), 423–447.

Ingram, H. M., & Smith, S. R. (1993). Public policy for democracy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Jardina, A. (2019). White identity politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Kam, C. D. (2010). Us against them: Ethnocentric foundations of American opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Larsen, C. A. (2011). Ethnic heterogeneity and public support for welfare: Is the American experience replicated in Britain, Sweden and Denmark? Scandinavian Political Studies, 34(4), 332–353.

Lieberman, R. C. (1998). Shifting The color line: Race and the American welfare state. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Luttig, M. D., Federico, C. M., & Lavine, H. (2017). Supporters and opponents of Donald Trump respond differently to racial cues: An experimental analysis. Research & Politics, 4(4), 2053168017737411.

Mau, S., & Burkhardt, C. (2009). Migration and welfare state solidarity in Western Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 19(3), 213–229.

Mettler, S. (2011). The submerged state: How invisible government policies undermine American democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miratrix, L. W., Sekhon, J. S., Theodoridis, A. G., & Campos, L. F. (2018). Worth weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments. Political Analysis, 26(3), 275–291.

Mullinix, K. J., Leeper, T. J., Druckman, J. N., & Freese, J. (2015). The generalizability of survey experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(2), 109–138.

Murray, C., & Kneebone, E.. (2017). The earned income tax credit and the white working class. Brookings: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2017/04/18/the-earned-income-tax-credit-and-the-white-working-class/.

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon mechanical turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5(5), 411.

Peffley, M., Hurwitz, J., & Sniderman, P. M. (1997). Racial stereotypes and Whites’ political views of blacks in the context of welfare and crime. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 30–60.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Schmidt-Catran, A. W., & Spies, D. C. (2016). Immigration and welfare support in Germany. American Sociological Review, 81(2), 242–261.

Schneider, A., & Ingram, H. (1990). Behavioral assumptions of policy tools. The Journal of Politics, 52(2), 510–529.

Schneider, A., & Ingram, H. (1993). Social construction of target populations: Implications for politics and policy. The American Political Science Review, 87(2), 334–347.

Schneider, A. L., & Ingram, H. M. (1997). Policy design for democracy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Schneider, A. L., & Ingram, H. M. (Eds.). (2005). Deserving and entitled. New York: SUNY Press.

Skocpol, T. (1991). Targeting within universalism: Politically viable policies to combat poverty in the United States. In C. Jencks & P. E. Peterson (Eds.), The urban underclass (pp. 411–436). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Skocpol, T. (1992). Protecting soldiers and mothers. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Soss, J., & Schram, S. F. (2007). A public transformed? Welfare reform as policy feedback. The American Political Science Review, 101(1), 111.

van Oorschot, W. (2006). Making the difference in social Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), 23–42.

Wetts, R., & Willer, R. (2018). Privilege on the precipice: Perceived racial status threats lead white americans to oppose welfare programs. Social Forces p. soy046.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy (Seco ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Winter, N. J. G. (2008). Dangerous frames: How ideas about race and gender shape public opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges funding support from the National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant program (Award Number SES-1264171) and research assistance from Grace Yousefi. The author would also like to thank Vincent Hutchings, Brendan Nyhan, Julianna Pacheco, Steven Perry, Joe Soss, and the editor and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Questionnaire

-

1.

We would like your opinion on a hypothetical federal government policy. Under this policy, people with lower incomes would receive assistance in the form of cash aid/a tax credit. [Also vary:] Only individuals that earn income through work would be eligible for this program. The government estimates that this policy would cost the U.S. Treasury about $73 billion per year.

Would you approve or disapprove of this program?

-

(a)

Strongly approve

-

(b)

Approve

-

(c)

Approve somewhat

-

(d)

Neither approve nor disapprove

-

(e)

Disapprove somewhat

-

(f)

Disapprove

-

(g)

Strongly disapprove

-

(a)

-

2.

Here is a list of different groups in American society. Which of these groups do you think are most likely to benefit from this program? You may select multiple groups.

-

Poor people

-

The unemployed

-

Working-class people

-

Middle-class people

-

Wealthy people

-

Big business

-

Small business

-

Labor unions

-

Whites

-

Blacks or African-Americans

-

Latino or Hispanic Americans

-

Asian Americans

-

Immigrants

-

Americans born in the United States

-

Men

-

Women

-

-

3.

Which political party do you believe would support this program?

-

(a)

Democrats

-

(b)

Republicans

-

(c)

Neither Democrats nor Republicans

-

(d)

Both Democrats and Republicans

-

(e)

Don’t know

-

(a)

-

4.

Do you think of yourself as a Democrat, a Republican, and Independent, or what?

-

(a)

Democrat

-

(b)

Republican

-

(c)

Independent

-

(d)

Other

-

(e)

No preference

-

(a)

-

5.

[If answered a or b to question 6] Would you consider yourself a strong Democrat/Republican, or a not very strong Democrat/Republican?

-

(a)

Strong

-

(b)

Not very strong

-

(a)

-

6.

[If answered c, d, or e to question 6] Do you think of yourself as closer to the Republican Party or the Democratic Party?

-

(a)

Closer to Republican

-

(b)

Closer to Democratic

-

(c)

Neither

-

(a)

-

7.

Where would you place yourself on this scale?

-

(a)

Very liberal

-

(b)

Liberal

-

(c)

Slightly liberal

-

(d)

Moderate; middle of the road

-

(e)

Slightly conservative

-

(f)

Conservative

-

(g)

Very conservative

-

(a)

-

8.

What is your age?

-

(a)

18 to 24

-

(b)

25 to 34

-

(c)

35 to 44

-

(d)

45 to 54

-

(e)

55 to 64

-

(f)

65 to 74

-

(g)

75 or older

-

(a)

-

9.

What racial or ethnic group best describes you?

-

(a)

White

-

(b)

Black

-

(c)

Hispanic

-

(d)

Asian

-

(e)

Native American

-

(f)

Mixed

-

(g)

Middle Eastern

-

(h)

Other

-

(a)

-

10.

What is your gender?

-

(a)

Male

-

(b)

Female

-

(a)

-

11.

Thinking back over the last year, what was your family’s income? [16-point ordinal scale]

-

12.

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

-

(a)

No high school

-

(b)

High school graduate

-

(c)

Some college

-

(d)

2-year degree

-

(e)

4-year degree

-

(f)

Post-graduate degree

-

(a)

-

13.

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? “Over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve.”

-

(a)

Agree strongly

-

(b)

Agree somewhat

-

(c)

Neither agree nor disagree

-

(d)

Disagree somewhat

-

(e)

Disagree strongly

-

(a)

-

14.

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? “Irish, Italian, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.” [same 5-point agree–disagree scale]

-

15.

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? “It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.” [same 5-point agree–disagree scale]

-

16.

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.” [same 5-point agree–disagree scale]

-

17.

Which comes closest to your view about what government policy should be toward unauthorized immigrants now living in the United States?

-

(a)

Make all unauthorized immigrants felons and send them back to their home country.

-

(b)

Have a guest worker program that allows unauthorized immigrants to remain.

-

(c)

Allow unauthorized immigrants to remain in the United States and eventually qualify for U.S. citizenship, but only if they meet certain requirements like paying back taxes and fines, learning English, and passing background checks.

-

(d)

Allow unauthorized immigrants to remain in the United States and eventually qualify for U.S. citizenship, without penalties.

-

(a)

-

18.

There is a proposal to allow people who were illegally brought into the U.S. as children to become permanent U.S. residents under some circumstances. Specifically, citizens of other countries who illegally entered the U.S. before age 16, who have lived in the U.S. 5 years or longer, and who graduated high school would be allowed to stay in the U.S. as permanent residents if they attend college or serve in the military. From what you have heard, do you favor, oppose, or neither favor nor oppose this proposal?

-

(a)

Favor

-

(b)

Oppose

-

(c)

Neither favor or oppose

-

(a)

-

19.

Some states have passed a law that will require state and local police to determine the immigration status of a person if they find that there is a reasonable suspicion that he or she is an undocumented immigrant. Those found to be in the U.S. without permission will have broken state law. From what you have heard, do you favor, oppose, or neither favor nor oppose these immigration laws?

-

(a)

Favor

-

(b)

Oppose

-

(c)

Neither favor or oppose

-

(a)

-

20.

Do you think the number of immigrants from foreign countries who are permitted to come to the United States to live should be [increased a lot, increased a little, left the same as it is now, decreased a little, or decreased a lot/decreased a lot, decreased a little, left the same as it is now, increased a little, or increased a lot]? [Randomly reverse order]

-

(a)

Increased a lot

-

(b)

Increased a little

-

(c)

Left the same as it is now

-

(d)

Decreased a little

-

(e)

Decreased a lot

-

(a)

-

21.

Now we’d like to ask you about immigration in recent years. How likely is it that recent immigration levels will take jobs away from people already here -- [extremely likely, very likely, somewhat likely, or not at all likely/not at all likely, somewhat likely, very likely, or extremely likely]? [Randomly reverse order]

-

(a)

Extremely

-

(b)

Very

-

(c)

Somewhat

-

(d)

Not at all

-

(a)

Appendix 2. Descriptive Statistics

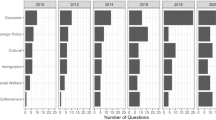

See Fig. 4.

Appendix 3. Representativeness of Sample

Table 9 displays summary measures for the Mechanical Turk sample on key demographic and political variables as compared to estimates for the US population. US Census Bureau estimates are calculated from the Census “QuickFacts” page (2016 estimates) and the annual population estimates by single year of age and sex for 2016. American National Election Studies (ANES) estimates are 95% confidence intervals calculated using full sample survey weights. Since two of the five questions used to construct the anti-immigration scale are missing from the 2016 ANES, I calculate a three-item version for comparison with the more recent benchmark (also rescaled to range from 0-1). A comparison with the 2012 benchmark for the full five-item version is also included.

Appendix 4. Alternative Models of Race and Nationality Assumptions

This appendix displays the results of a series of alternative specifications of the “assumption” models presented in Tables 1 and 2 in the main text. Table 10 adds interaction terms of the treatments with education. Tables 11 and 12 add interaction terms of the treatments with ideology and party identification, respectively. Tables 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 show the results of multinomial logit models that treat assumptions about each group as separate outcomes.

Appendix 5. Alternative Specifications of Policy Approval Models

This appendix displays the results of alternative specifications of the OLS regressions of policy approval displayed in Table 3 in the main text.

Tables 18 and 19 displays the results of models that treat the assumptions that minority groups will benefit and that majority groups will benefit as separate variables. Figures 5 and 6 display these results graphically.

Tables 20 and 21 add interactions of the minority group assumptions with ideology and party identification, respectively.

Table 22 incorporates a dummy variable for the assumption that only the Democratic party supports the policy, with interaction terms with the relevant attitudinal variables.

Appendix 6. Analysis of Effects Across Overrepresented and Underrepresented Subgroups

This section graphically presents the results of models using interaction terms of the independent variables of interest in the main analysis with indicators identifying subgroups of respondents that are underrepresented in the sample. These results suggest how the central findings of the study might change if a more representative sample were used. Separate analyses were conducted for age (18 to 34 vs. 35 and up), ideology (liberals vs. moderates and conservatives), party identification (Democrats vs. Republicans and independents), gender (male vs. female), race (non-Hispanic whites vs. nonwhites and Hispanics), education (4-year degree and higher vs. no 4-year degree), and income (less than $50,000 vs. $50,000 and up). For each variable, categories were divided to maximize the size of the group that is underrepresented in the sample.

Effects of the work requirement treatment (collapsing across the tax vs. cash payment conditions) on the assumption that blacks will benefit to the exclusion of whites, and that immigrants will benefit to the exclusion of native-born Americans, are explored in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively. The effects of these assumptions on policy approval in interaction with symbolic racism and the anti-immigration scale are explored in Figs. 9 and 10.

Appendix 7. Replication of Analyses using Survey Weights

Survey weights were generated using the ipfweight command in Stata (Bergmann 2011), based on American Community Survey estimates for race and ethnicity, age, gender, and income of the adult population for 2016. Specifically, the sample was weighted based on the following percentages for specific groups that are overrepresented or underrepresented in the data:

-

Age 18 to 34: 30.4%

-

Age 55 and up: 35.2%

-

Female: 51%

-

White, non-Hispanic: 67%

-

African-American: 13%

-

White Latino/Hispanic (proxy for people who would identify as “Hispanic” in the question): 14.5%

-

Four-year degree or higher: 30%

-

Income $75,000 and up: 36.8%

As recommended by Bergmann , I limit survey weights to a maximum of 5 for each respondent (Tables 23, 24, and 25).

Appendix 8. Mediated Moderation Analyses

The plots displayed in Fig. 3 are derived from a structural equation model and subsequent calculations recommended by Preacher, Rucker and Hayes (2007, see, in particular, Model 3 and Equation 20). These models take the following form:

The first model is a linear probability model, which facilitates the calculation of mediated effects. The indirect or mediated effect of workreq is \(\hat{a}_{1}(\hat{b}_{1} + \hat{b}_{3}attitude)\), and is distinct from the direct effect of the treatment on policy approval represented by \(\hat{c'}\). The standard error of the mediated effect is calculated with the following equation:

These are “normal theory” standard errors that rely on an assumption that the product of \(\hat{a}_{1}\) \(\hat{b}_{1}\) is normally distributed, though this can be relaxed for large samples. Preacher et al. (2007) recommend bootstrapped standard errors to obviate the need for this assumption. As a robustness check, I also ran bootstrapped structural equation models with 10,000 repetitions and compared the standard errors for the effects of the work requirement treatment at the mean values of the attitude variables and one standard deviation above and below the mean. In all cases, the bootstrapped standard errors are virtually identical to those calculated with the normal theory method. The results of the two structural equation models are displayed in Tables 26 and 27.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haselswerdt, J. Who Benefits? Race, Immigration, and Assumptions About Policy. Polit Behav 44, 271–318 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09608-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09608-3