Abstract

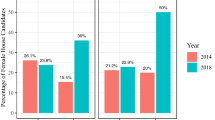

Party elites and voters are reluctant to cede multiple ballot positions to women simultaneously, so that men are able to have running mates of either gender but women tend to have male running mates. Evidence from American gubernatorial elections, state legislative caucuses, and presidential tickets from around the world confirms this: nominating a woman for the top position reduces a party’s likelihood of nominating a woman for the second position by half or more.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The prior occasions where major-party gubernatorial nominations were both women (Hawaii in 2002, Nebraska in 1986) also featured men as the associated lieutenant-governor candidates.

Currently, women comprise 21 % of national parliamentarians worldwide (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2013). Since the 1970s, women presidents, prime ministers and chancellors have increased from three to more than twenty (Hawkesworth 2012). In the United States, women hold 17 % of mayoral positions (of cities with more than 30,000 residents), 24 % of state legislative seats, 23 % of statewide elective executive positions, and 18 % of Congressional seats in the United States (Center for American women in politics 2013).

Some suggest that the sacrificial lamb theory held in earlier decades but no longer applies (Welch and Studlar 1996), or that sacrificial-lamb strategies are partisan, with right-leaning parties being more likely to nominate women as sacrificial lambs (Cooperman and Oppenheimer 2001; Ryan et al. 2010; Sanbonmatsu 2002; Stambough and O’Regan 2007).

Strictly speaking, candidates for lieutenant governor are not always on the same “ticket” as are those for governor: in some states the offices are formally elected separately, and winners can be from opposite parties. We thus refer generically to a party “slate” when discussing candidates who are on the same ballot representing the same party but may not be part of a package deal.

If nominators worry that femaleness will harm electoral prospects or that women are less suited for a hard-fought campaign, races expected to be close may be less apt to see female candidates (Palmer and Simon 2008). Polls’ tendency to understate female-candidate performance (Stout and Kline 2011) may further hinder women’s chances of being nominated in competitive races: a poorly-polling running mate might be avoided for fear of costing the otherwise winnable election. Competitiveness may then have non-linear effects, with women less often nominated for close races than for blowouts in either direction. Allowing this sort of effect with a quadratic term on margin of victory does not noticeably affect the coefficients of interest; nor does it come up significant itself.

It may not always be clear whether the opposing party or parties will nominate female candidates (e.g., if parties have simultaneous primaries), but even there front-runners offer some information about the likelihood of females being selected.

State fixed effects force the exclusion of New Jersey, which has only had female major-party candidates in its short history of having a directly elected lieutenant governor.

Using year fixed-effects gives virtually identical results, but odd years often drop from the analysis because the few elections often feature lieutenant-governor candidates all of one gender.

Though by no means definitive, the similar results argue against the possibility that the results here reflect candidate supply rather than demand—i.e., that women may be less likely to put themselves forward as candidates for office when women are also running for other offices.

This is a noisy measure. Many resignations see a sitting governor leaving office a few days early to enter Congress, leaving very little time for the ex-lieutenant governor to attain authority.

These include eight in Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, the Seychelles, and Tanzania), four in Asia (Indonesia, the Maldives, the Philippines, and Taiwan), one in Europe (Bulgaria), and 15 in Latin America (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay) along with the United States.

The sex of vice-presidential candidates is unknown for one slate in Honduras in 2001 and another in the Seychelles in 1998. In both cases, the presidential nominee was male, so even if the vice-presidential candidates were male, reported results would change relatively little.

Countries have concurrently had female presidents and vice-presidents (Nicaragua 1996–1997, Switzerland on multiple occasions), but the women involved did not face the electorate jointly.

OLS and penalized-likelihood models can cope with Table 4 distribution of observations. Multivariate regressions of both types, featuring controls for region, time trend, and a binary variable indicating leftist parties (Schmidt 2009), had coefficients with larger magnitude and t statistics than did the analogous bivariate regressions without controls. Though not definitive, this suggests that Table 4 results are not a spurious consequence of its lack of control variables.

References

Arceneaux, K. (2001). The ‘Gender Gap’ in state legislative representation: New data to tackle an old question. Political Research Quarterly, 54(1), 143–160.

Ashe, J., & Stewart, K. (2012). Legislative recruitment: Using diagnostic testing to explain underrepresentation. Party Politics, 18(5), 687–707.

Atkeson, L. R. (2003). Not all cues are created equal: The conditional impact of female candidates on political engagement. Journal of Politics, 65(4), 1040–1061.

Baer, D. L. (2013). Welcome to the party? Leadership, ambition, and support among elites. In M. Rose (Ed.), Women & executive office: Pathways and performance (pp. 181–207). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Blais, A., & Lago, I. (2009). A general measure of district competitiveness. Electoral Studies, 28(1), 94–100.

Bratton, K. A., & Spill, R. L. (2002). Existing diversity and judicial selection: The role of the appointment method in establishing gender diversity in state supreme courts. Social Science Quarterly, 83(2), 504–518.

Burns, N., Schlozman, K., & Verba, S. (2001). The private roots of public action: Gender, equality, and political participation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Carroll, S. J. (1985). Women as candidates in American politics. Bloomington, IN: Indiana.

Carroll, S. J., & Sanbonmatsu, K. (2013). Entering the mayor’s office: Women’s decisions to run for municipal positions. In M. Rose (Ed.), Women & executive office: Pathways and performance (p. 115). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Caul, M. (2001). Political parties and the adoption of candidate gender quotas: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Politics, 63(4), 1214–1229.

Center for American Women in Politics. (2013). “Facts on Women Officeholders, Candidates, and Voters.” Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/fast_facts/index.php.

Cheng, C., & Tavits, M. (2011). Informal influences in selecting female political candidates. Political Research Quarterly, 64(2), 460–471.

Cooperman, R., & Oppenheimer, B. I. (2001). The gender gap in the House of Representatives. In L. C. Dodd & B. I. Oppenheimer (Eds.), Congress reconsidered (p. 125). Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (2000). Gender and political knowledge. In S. Tolleson-Rinehart & J. J. Josephson (Eds.), Gender and American politics: Women, men, and the political process (p. 21). London: M.E. Sharpe.

Duerst-Lahti, G. (1997). Reconceiving theories of power: Consequences of masculinism in the executive branch. In M. A. Borelli & J. M. Martin (Eds.), The other elites (p. 11). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Esteve-Volart, B., & Bagues, M. (2012). Are women pawns in the political game? Evidence from elections to the Spanish Senate. Journal of Public Economics, 96(3), 387–399.

Flammang, J. A. (1997). Women’s political voice: How women are transforming the practice and study of politics. Philadelphia: Temple.

Fowler, L. L., & McClure, R. D. (1989). Political ambition: Who decides to run for Congress?. New Haven, CT: Yale.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2004). Entering the arena? Gender and the decision to run for office. American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 264–280.

Fox, R. L., & Oxley, Z. M. (2003). Gender stereotyping in state executive elections: Candidate selection and success. Journal of Politics, 65(3), 833–850.

Fulton, S. A., & Ondercin, H. L. (2013). Does sex encourage commitment? The impact of candidate choices on the time-to-decision. Political Behavior, 35(4), 665–686.

Gertzog, I. N., & Simard, M. M. (1981). Women and ‘Hopeless’ congressional candidacies: Nomination frequency, 1916–1978. American Politics Research, 9(4), 449–466.

Hawkesworth, M. (2012). Political worlds of women: Activism, advocacy, and governance in the twenty-first century. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hinojosa, M., & Gurdián, A. V. (2012). Alternate paths to power? Women’s political representation in Nicaragua. Latin American Politics and Society, 54(4), 61–88.

Hogan, R. E. (2001). The influence of state and district conditions on the representation of women in U.S. state legislatures. American Politics Research, 29(1), 4–24.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Inter-Parliamentary Union. 2013. “Women in National Parliaments: April 1, 2013.” http://www.ipu.org.

Isom, W. R. (1938). The office of lieutenant-governor in the states. American Political Science Review, 32(5), 921–926.

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 965–990.

Koch, J. W. (2000). Do citizens apply gender stereotypes to infer candidates’ ideological orientations? Journal of Politics, 62(2), 414–429.

Krook, M. L., Lovenduski, J., & Squires, J. (2009). Gender quotas and models of political citizenship. British Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 781–803.

Latu, I. M., Stewart, T. L., Myers, A. C., Lisco, C. G., Estes, S. B., & Donahue, D. K. (2011). What we ‘Say’ and what we ‘Think’ about Female managers: Explicit versus implicit associations of women with success. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(2), 252–266.

Lawless, J. L., & Fox, R. L. (2010). It still takes a candidate: Why women don’t run for office. New York: Cambridge.

Loftus, B. (2008). Dominant culture interrupted: Recognition, resentment and the politics of change in an english police force. British Journal of Criminology, 48(6), 756–777.

Martin, J. M. (1989). The recruitment of women to cabinet and subcabinet posts. Western Political Quarterly, 42(1), 161–172.

McDonald, S. (2011). What’s in the ‘Old Boys’ network? Accessing social capital in gendered and racialized networks. Social Networks, 33(4), 317–330.

Meeks, L. (2012). Is she ‘Man Enough’? Women candidates, executive political offices, and news coverage. Journal of Communication, 62(1), 175–193.

Nechemias, C. (1987). Changes in the election of women to U. S. state legislative seats. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 12(1), 125–142.

Niven, D. (1998). The missing majority: The recruitment of women as state legislative candidates. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Niven, D. (2006). Throwing your hat out of the ring: Negative recruitment and the gender imbalance in state legislative candidacy. Politics & Gender, 2(4), 473–489.

O’Brien, D. Z. (2012). Gender and select committee elections in the British House of Commons. Politics & Gender, 8(2), 178–204.

O’Regan, V., & Stambough, S. J. (2011). The novelty impact: The politics of trailblazing women in gubernatorial elections. Journal of Women, Politics, & Policy, 32(2), 96–113.

Oxley, Z. M., & Fox, R. L. (2004). Women in executive office: Variation across American States. Political Research Quarterly, 57(1), 113–120.

Palmer, B., & Simon, D. (2005). When women run against women: The hidden influence of female incumbents in elections to the U.S. House of Representatives, 1956–2002. Politics & Gender, 1(1), 39–63.

Palmer, B., & Simon, D. (2008). Breaking the political glass ceiling: Women and congressional elections. New York: Routledge.

Paxton, P., & Hughes, M. (2007). Women, politics, and power: A global perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press/Sage.

Philpot, T. S., & Walton, H, Jr. (2007). One of our own: Black female candidates and the voters who support them. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 49–62.

Plüss, L., & Rusch, M. (2012). Der Gender Gap in Schweizer Stadtparlamenten. Swiss Political Science Review, 18(1), 54–77.

Riccucci, N. M., & Saidel, J. R. (2001). The demographics of gubernatorial appointees: Toward explanation of variation. Policy Studies Journal, 29(1), 11–22.

Roth, L. M. (2004). The social psychology of tokenism: Status and homophily processes on wall street. Sociological Perspectives, 47(2), 189–214.

Ryan, M. K., Alexander Haslam, S., & Kulich, C. (2010). Politics and the glass cliff: Evidence that women are preferentially selected to contest hard-to-win seats. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(1), 56–64.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Political parties and the recruitment of women to state legislatures. Journal of Politics, 64(3), 791–809.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2006). Where women run: Gender and party in the American states. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Schmidt, G. D. (2009). The election of women in list PR systems: Testing the conventional wisdom. Electoral Studies, 28(2), 190–203.

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2011). Women who win: Social backgrounds, paths to power, and political ambition in Latin American legislatures. Politics and Gender, 7(1), 1–33.

Scola, B. (2013). Predicting presence at the intersections: Assessing the variation in women’s office holding across the states. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 13(3), 333–348.

Shair-Rosenfield, S. (2012). The alternative incumbency effect: Electing women legislators in Indonesia. Electoral Studies, 31(3), 576–587.

Sigelman, L., & Wahlbeck, P. J. (1997). The ‘Veepstakes’: Strategic choice in presidential running mate selection. American Political Science Review, 91(4), 855–864.

Smooth, W. G. (2008). Gender, race, and the exercise of power and influence. In B. Reingold (Ed.), Legislative women: Getting elected, getting ahead (pp. 175–196). Lynne Rienner: Boulder.

Stambough, S. J., & O’Regan, V. R. (2007). Republican lambs and the democratic pipeline: Partisan differences in the nomination of female gubernatorial candidates. Politics & Gender, 3(3), 349–368.

Stout, C. T., & Kline, R. (2011). I’m not voting for her: Polling discrepancies and female candidates. Political Behavior, 33(3), 479–503.

Studlar, D. T., & Moncrief, G. F. (1999). Women’s work? The distribution and prestige of portfolios in the Canadian Provinces. Governance, 12(4), 379–395.

Thomas, M. (2012). The complexity conundrum: Why hasn’t the gender gap in subjective political competence closed? Canadian Journal of Political Science, 45(2), 337–358.

Thomas, M., & Bodet, M. A. (2013). Sacrificial lambs, women candidates, and district competitiveness in Canada. Electoral Studies, 32(1), 153–166.

Ulbig, S. G. (2010). The appeal of second bananas: The impact of vice presidential candidates on presidential vote choice, yesterday and today. American Politics Research, 38(2), 330–355.

Verba, S., Burns, N., & Schlozman, K. (1997). Knowing and caring about politics: Gender and political engagement. Journal of Politics, 59(4), 1051–1072.

Welch, S., & Studlar, D. T. (1996). The opportunity structure for women’s candidacies and electability in Britain and the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 49(4), 861–874.

Winder, D. W., & Hill, D. (2006). The governor and the lieutenant governor: Forms of cooperation between two state executives. Politics & Policy, 34(3), 634–656.

Windett, J. H. (2011). State effects and the emergence and success of female gubernatorial candidates. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 11(4), 460–482.

Wolbrecht, C., & Campbell, D. E. (2007). Leading by example: Female members of parliament as political role models. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 921–939.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hennings, V.M., Urbatsch, R. There Can Be Only One (Woman on the Ticket): Gender in Candidate Nominations. Polit Behav 37, 749–766 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9290-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9290-4