Abstract

Purpose

Hypothalamic obesity (HO) is a complication associated with craniopharyngioma (CP). Attempts have been made to perioperatively predict the development of this complication, which can be severe and difficult to treat.

Methods

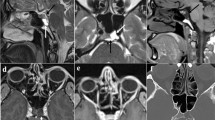

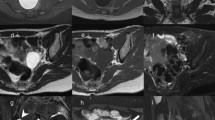

Patients who underwent first transsphenoidal surgical resection in a single center between February 2005 and March 2019 were screened; those who have had prior surgery or radiation, were aged below 18 years, or did not have follow up body mass index (BMI) after surgery were excluded. Primary end point was BMI within 2 years post-surgery. Hypothalamic involvement (HI) was graded based on preoperative and postoperative imaging with regards to anterior, posterior, left and right involvement. Data on baseline demographics, pre-operative and post-operative MRI, and endocrine function were collected.

Results

45 patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Most patients in our cohort underwent gross total resection (n = 35 patients). 13 patients were from no HI or anterior HI only group and 22 patients were classified as both anterior (ant) and posterior (post) HI group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the gross total, subtotal or near total resection. Pre-operative BMI and post-operative BMI were significantly higher in patients who had ant and post HI on pre-operative MRI (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively). Similarly, post-operative BMI at 13–24 months was also significantly higher in the ant and post HI group on post-op MRI (p < 0.01). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of baseline adrenal insufficiency, thyroid insufficiency, gonadal insufficiency, IGF-1 levels, hyperprolactinemia, and diabetes insipidus. Diabetes insipidus was more common following surgery among those who had anterior and posterior involvement on pre-operative MRI (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

HO appears to be predetermined by tumor involvement in the posterior hypothalamus observed on pre-operative MRI. Posterior HI on pre-operative MRI was also associated with the development of diabetes insipidus after surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ordonez-Rubiano EG, Forbes JA, Morgenstern PF et al (2018) Preserve or sacrifice the stalk? Endocrinological outcomes, extent of resection, and recurrence rates following endoscopic endonasal resection of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.6.JNS18901

van Iersel L, Brokke KE, Adan RAH, Bulthuis LCM, van den Akker ELT, van Santen HM (2019) Pathophysiology and individualized treatment of hypothalamic obesity following craniopharyngioma and other suprasellar tumors: a systematic review. Endocr Rev 40(1):193–235. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2018-00017

Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, Preston-Martin S, Davis F, Bruner JM (1998) The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg 89(4):547–551. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0547

Pereira AM, Schmid EM, Schutte PJ et al (2005) High prevalence of long-term cardiovascular, neurological and psychosocial morbidity after treatment for craniopharyngioma. Clin Endocrinol 62(2):197–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02196.x

Sterkenburg AS, Hoffmann A, Gebhardt U, Warmuth-Metz M, Daubenbuchel AMM, Muller HL (2015) Survival, hypothalamic obesity, and neuropsychological/psychosocial status after childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: newly reported long-term outcomes. Neuro-oncology 17(7):1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nov044

Yang I, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ et al (2010) Craniopharyngioma: a comparison of tumor control with various treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus 28(4):E5

Tan TSE, Patel L, Gopal-Kothandapani JS et al (2017) The neuroendocrine sequelae of paediatric craniopharyngioma: a 40-year meta-data analysis of 185 cases from three UK centres. Eur J Endocrinol 176(3):359–369. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-16-0812

Wijnen M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Janssen JAMJL et al (2017) Very long-term sequelae of craniopharyngioma. Eur J Endocrinol 176(6):755–767. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-17-0044

Cohen M, Guger S, Hamilton J (2011) Long term sequelae of pediatric craniopharyngioma—literature review and 20 years of experience. Front Endocrinol 2:81–81. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2011.00081

Park SW, Jung HW, Lee YA et al (2013) Tumor origin and growth pattern at diagnosis and surgical hypothalamic damage predict obesity in pediatric craniopharyngioma. J Neurooncol 113(3):417–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-013-1128-0

Andereggen L, Hess B, Andres R et al (2018) A ten-year follow-up study of treatment outcome of craniopharyngiomas. Swiss Med Wkly 148:w14521. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14521

Tosta-Hernandez PDC, Siviero-Miachon AA, da Silva NS, Cappellano A, de Pinheiro M, Spinola-Castro AM (2018) Childhood craniopharyngioma: a 22-year challenging follow-up in a single center. Horm Metab Res 50(9):675–682. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0641-5956

Karavitaki N, Brufani C, Warner JT et al (2005) Craniopharyngiomas in children and adults: systematic analysis of 121 cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol 62(4):397–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02231.x

Lo AC, Howard AF, Nichol A et al (2014) Long-term outcomes and complications in patients with craniopharyngioma: the British Columbia Cancer Agency experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 88(5):1011–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.019

Bagnasco M, Tulipano G, Melis MR, Argiolas A, Cocchi D, Muller EE (2003) Endogenous ghrelin is an orexigenic peptide acting in the arcuate nucleus in response to fasting. Regul Pept 111(1–3):161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00283-5

Belgardt BF, Okamura T, Brüning JC (2009) Hormone and glucose signalling in POMC and AgRP neurons. J Physiol 587(Pt 22):5305–5314. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179192

Berthoud HR, Jeanrenaud B (1979) Acute hyperinsulinemia and its reversal by vagotomy after lesions of the ventromedial hypothalamus in anesthetized rats. Endocrinology 105(1):146–151. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-105-1-146

Monroe MB, Seals DR, Shapiro LF, Bell C, Johnson D, Parker JP (2001) Direct evidence for tonic sympathetic support of resting metabolic rate in healthy adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280(5):E740-744. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.5.E740

Holmer H, Ekman B, Björk J et al (2009) Hypothalamic involvement predicts cardiovascular risk in adults with childhood onset craniopharyngioma on long-term GH therapy. Eur J Endocrinol 161(5):671–679. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-09-0449

Muller HL, Faldum A, Etavard-Gorris N et al (2003) Functional capacity, obesity and hypothalamic involvement: cross-sectional study on 212 patients with childhood craniopharyngioma. Klin Padiatr 215(6):310–314. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-45499

Roth CL (2015) Hypothalamic obesity in craniopharyngioma patients: disturbed energy homeostasis related to extent of hypothalamic damage and its implication for obesity intervention. J Clin Med 4(9):1774–1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm4091774

Schneeberger M, Gomis R, Claret M (2014) Hypothalamic and brainstem neuronal circuits controlling homeostatic energy balance. J Endocrinol 220(2):T25-46. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-13-0398

Babcock Gilbert S, Roth LW (2015) Hypothalamic obesity. Minerva Endocrinol 40(1):61–70

Brobeck JR, Tepperman J, Long CN (1943) Experimental hypothalamic hyperphagia in the albino rat. Yale J Biol Med 15(6):831–853

De Vile CJ, Grant DB, Kendall BE et al (1996) Management of childhood craniopharyngioma: can the morbidity of radical surgery be predicted? J Neurosurg 85(1):73–81. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1996.85.1.0073

Elliott RE, Sands SA, Strom RG, Wisoff JH (2010) Craniopharyngioma Clinical Status Scale: a standardized metric of preoperative function and posttreatment outcome. Neurosurg Focus 28(4):E2. https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.2.FOCUS09304

Elowe-Gruau E, Beltrand J, Brauner R et al (2013) Childhood craniopharyngioma: hypothalamus-sparing surgery decreases the risk of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(6):2376–2382. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-3928

Fjalldal S, Follin C, Gabery S et al (2019) Detailed assessment of hypothalamic damage in craniopharyngioma patients with obesity. Int J Obes 43(3):533–544. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0185-z

Mortini P, Gagliardi F, Bailo M et al (2016) Magnetic resonance imaging as predictor of functional outcome in craniopharyngiomas. Endocrine 51(1):148–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-015-0683-x

Van Gompel JJ, Nippoldt TB, Higgins DM, Meyer FB (2010) Magnetic resonance imaging-graded hypothalamic compression in surgically treated adult craniopharyngiomas determining postoperative obesity. Neurosurg Focus 28(4):E3. https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.1.FOCUS09303

Bogusz A, Boekhoff S, Warmuth-Metz M, Calaminus G, Eveslage M, Müller HL (2019) Posterior hypothalamus-sparing surgery improves outcome after childhood craniopharyngioma. Endocr Connect 8(5):481–492. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-19-0074

Joly-Amado A, Cansell C, Denis RGP et al (2014) The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus and the control of peripheral substrates. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 28(5):725–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2014.03.003

King BM (2006) The rise, fall, and resurrection of the ventromedial hypothalamus in the regulation of feeding behavior and body weight. Physiol Behav 87(2):221–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.10.007

Roth CL, Eslamy H, Werny D et al (2015) Semiquantitative analysis of hypothalamic damage on MRI predicts risk for hypothalamic obesity. Obesity 23(6):1226–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21067

Daubenbüchel AMM, Müller HL (2015) Neuroendocrine disorders in pediatric craniopharyngioma patients. J Clin Med 4(3):389–413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm4030389

Müller HL (2016) Craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic injury: latest insights into consequent eating disorders and obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 23(1):81–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000214

Roth CL (2011) Hypothalamic obesity in patients with craniopharyngioma: profound changes of several weight regulatory circuits. Front Endocrinol 2:49. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2011.00049

van Swieten MMH, Pandit R, Adan RAH, van der Plasse G (2014) The neuroanatomical function of leptin in the hypothalamus. J Chem Neuroanat 61–62:207–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchemneu.2014.05.004

Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG (2000) Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404(6778):661–671. https://doi.org/10.1038/35007534

Roth C, Wilken B, Hanefeld F, Schröter W, Leonhardt U (1998) Hyperphagia in children with craniopharyngioma is associated with hyperleptinaemia and a failure in the downregulation of appetite. Eur J Endocrinol 138(1):89–91. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje.0.1380089

Fruhwürth S, Vogel H, Schürmann A, Williams KJ (2018) Novel insights into how overnutrition disrupts the hypothalamic actions of leptin. Front Endocrinol 9:89. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00089

Kwon O, Kim KW, Kim MS (2016) Leptin signalling pathways in hypothalamic neurons. Cell Mol Life Sci 73(7):1457–1477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2133-1

Timper K, Brüning JC (2017) Hypothalamic circuits regulating appetite and energy homeostasis: pathways to obesity. Dis Model Mech 10(6):679–689. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.026609

Tokunaga K, Bray GA, Matsuzawa Y (1993) Improved yield of obese rats using a double coordinate system to locate the ventromedial or paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res Bull 32(2):191–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-9230(93)90074-L

Schoelch C, Hübschle T, Schmidt I, Nuesslein-Hildesheim B (2002) MSG lesions decrease body mass of suckling-age rats by attenuating circadian decreases of energy expenditure. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283(3):E604-611. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00439.2001

Roth CL, Blevins JE, Ralston M et al (2011) A novel rodent model that mimics the metabolic sequelae of obese craniopharyngioma patients. Pediatr Res 69(3):230–236. https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182083b67

Godil SS, Tosi U, Gerges M et al (2021) Long-term tumor control after endoscopic endonasal resection of craniopharyngiomas: comparison of gross-total resection versus subtotal resection with radiation therapy. J Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.3171/2021.5.JNS202011

Grewal MR, Spielman DB, Safi C et al (2020) Gross total versus subtotal surgical resection in the management of craniopharyngiomas. Allergy Rhinol 11:2152656720964158. https://doi.org/10.1177/2152656720964158

Yuen KCJ, Kołtowska-Häggström M, Cook DM et al (2014) Primary treatment regimen and diabetes insipidus as predictors of health outcomes in adults with childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99(4):1227–1235. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-3631

Müller HL, Emser A, Faldum A et al (2004) Longitudinal study on growth and body mass index before and after diagnosis of childhood craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(7):3298–3305. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-031751

Patel KS, Raza SM, McCoul ED et al (2015) Long-term quality of life after endonasal endoscopic resection of adult craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg 123(3):571–580. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.12.JNS141591

Lemaire JJ, Nezzar H, Sakka L et al (2013) Maps of the adult human hypothalamus. Surg Neurol Int 4(Suppl 3):S156–S163. https://doi.org/10.4103/2152-7806.110667

Acknowledgements

Anjile An, MPH, was partially supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science of the National Institute of Health under Award number UL1TR002384.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GAD contributed to the study conception and design. Surgeries were performed by BC, RR, and THS. Material preparation and data collection were performed by KNR. Radiology imaging analysis were performed by SBS, CDP, and JEL. Radiology figures were prepared by SBS. Statistical analysis was performed by AA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by KNR and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Informed consent

Not required for this study type.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rachmasari, K.N., Strauss, S.B., Phillips, C.D. et al. Posterior hypothalamic involvement on pre-operative MRI predicts hypothalamic obesity in craniopharyngiomas. Pituitary 26, 105–114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-022-01294-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-022-01294-0