Abstract

What grounds facts of ground? Some metaphysicians invoke fundamental grounding laws to answer this question. These are general principles that link grounded facts to their grounds. The main business of this paper is to advance the debate about the metaphysics of grounding laws by exploring the prospects of a plausible yet underexplored minimalist account, one which is structurally analogous to a familiar Humean conception of natural laws. In the positive part of this paper, I articulate such a novel view and argue for its merits. The minimalist account shuns essences and takes laws to be unmysterious elite regularities. Therefore, it is a promising alternative for theorists of ground who spurn the acceptance of essentialism about the grounding laws but think that these are needed in our theorizing. In the negative part, I argue that widely accepted principles of ground, coupled with the tenets of minimalism, jeopardize the fundamentality of the grounding laws. I discuss two immediately available and prima facie appealing strategies to evade this threat. However, I show that both have undesirable theoretical costs. I conclude by casting doubts on whether the benefits of a minimalist account of fundamental grounding laws outweigh such costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Grounds for what grounds what

Many important philosophical disputes concern a peculiar kind of non-causal dependence. Do mental facts depend on physical facts? Do facts about someone’s knowledge depend on facts about their total evidence? Do facts about what is necessary to an object depend on facts about what is essential to it? The list might continue.

Theorists of ground would argue that these are questions about what grounds what. As I understand it, ground is a form of non-causal yet determinative relation with explanatory import among facts. Here I assume that facts are worldly entities whose constituents are objects, properties, relations, and other worldly items. I also assume that if one fact grounds another, both obtain. I use f and g as variables for singular facts and Greek letters, such as Γ and Δ, for pluralities thereof. Sometimes I write [ϕ] for ‘the fact that ϕ’, where ϕ is a schematic sentential variable. If the enclosed sentence has an internal syntactic structure, I assume that the corresponding fact is about its constituents. For instance, [Clelia is smart] is a fact having the individual Clelia and the property of being smart as constituents. For the sake of simplicity, I will assume that facts are structured like sentences in the language of first-order logic and its extensions. But I am not committed to the claim that there is a property for every predicate. Nor do I have to say that there is a fact corresponding to the structure of every true sentence. In this sense, ground is worldly. Informally, ground captures the idea that some facts obtain because or in virtue of others in some distinctive metaphysical fashion. One might say, for example, that fact that {Hypatia} exists is grounded in and thus metaphysically explained by the fact that Hypatia exists.

It is orthodoxy amongst grounders that grounds (i.e., facts that do the grounding) are more fundamental than the facts they ground (e.g., Rosen, 2010, p. 116; Raven, 2012, p. 689; Bennett, 2017, p. 40; Rabin, 2018, p. 42). It is also standard to define or characterize the fundamental facts as those which are ungrounded (e.g., Schaffer, 2009, p. 373; Rosen, 2010, p. 112; Audi, 2012, p. 710; Bennett, 2017, p. 106; Leuenberger, 2020, p. 2648). These principles, which will take centre stage later, can be formulated as follows.

Ungroundedness:

f is fundamental if and only if there is no plurality of facts Γ that is a ground of f.

G→MFT:

if f grounds g, then f is more fundamental than g.Footnote 1

Because of its connection with fundamentality, ground is a serviceable tool for investigating the structure of reality. Canonically, ground is taken to be irreflexive, asymmetric, and transitive. Thus it is said to induce strict partial order among facts (though not everyone agrees; for example, see Jenkins, 2011; Schaffer, 2012; Wilson, 2014).

Theorists of ground face an unfamiliar question: what grounds facts of ground? Suppose that f grounds g. What grounds the fact that f grounds g? This is the question of iterated ground (or it is one of the questions of iterated ground; see Kovacs, 2020a). The main business of this paper is to advance the debate concerning what grounds facts of grounds, or grounding facts. To this end, I explore a novel and prima facie attractive minimalist account of grounding laws that is structurally analogous to a familiar Humean conception of laws of nature. On the minimalist view, facts of the form ‘f grounds g’ are grounded in unmysterious elite regularities that systematize patterns of facts grounding other facts. I will argue that this view is well-motivated and has compelling merits. For example, it joins grounds and grounded together without appealing to essences. It is, therefore, a promising alternative for those who spurn metaphysical movers of this sort. Another selling point of this approach is that it allows for the possibility of contingent grounding laws. Those metaphysicians who think that even the laws of ground ought to be contingent are thus invited to take the proposed minimalist account seriously. In the negative part of the paper, however, I will show that widely accepted principles of ground, coupled with the defining principles of minimalism, jeopardize the fundamentality of the grounding laws. The upshot is problematic because, as I will explain in due course, there are prima facie compelling reasons to hold that some grounding laws are fundamental. There are two immediately available and superficially appealing strategies to evade this threat. Unfortunately, both have undesirable theoretical costs. I conclude by casting doubts on whether the benefits of a minimalist account of fundamental grounding laws outweigh such costs.

Someone might contend that the question of iterated ground is a symptom of a degenerate research programme. However, such a reaction would be ill-conceived. At least three reasons justify the relevance of the investigation of what grounds the grounding facts:

-

(1)

Implications concerning the structure of reality. Under the adoption of G → MFT, whatever grounds facts of ground is more fundamental than such facts. If the fact that f grounds g is grounded in some fact c, this is more fundamental than the fact that f grounds g.

-

(2)

Connections to metaphysical explanation. Ground is intimately connected to metaphysical explanation.Footnote 2Unionists say that ground is metaphysical explanation (e.g., Fine, 2012; Litland, 2017; Raven, 2012). Whenever f grounds g, f metaphysically explains g. Separatists claim that ground is not metaphysical explanation but backs or support metaphysical explanation. Whenever f grounds g, f backs or supports a metaphysical explanation of g. Seekers of metaphysical explanation face an analogous question: what metaphysically explains the fact that f metaphysically explains g? An answer to the question of iterated ground may illuminate an answer to this question. Whatever grounds the fact that f grounds g can be said to metaphysically explain or back a metaphysical explanation of this fact of ground.Footnote 3

-

(3)

Completeness. A complete theory of ground must specify the grounds of facts of ground. Without an account of how these facts are grounded, we cannot evaluate the theory properly.

The plan is as follows. In the remainder of this section, I clarify an important distinction between full and partial grounds. In Sect. 2, I outline what I call nomic approaches to iterated ground. In Sect. 3, I develop and motivate the minimalist account of laws of ground. In Sect. 4, I introduce the thesis that some grounding laws are fundamental and argue that the minimalist ought to embrace it. However, I show that widely shared principles about ground undermine the fundamentality of minimalist grounding laws. To evade this threat, I devote Sects. 5 and 6 to discuss two prima facie attractive strategies that can be found in the literature. But, as I mentioned above, my conclusion will be negative: both strategies have undesirable theoretical costs.

Now we need to clarify a distinction between partial and full grounds. To illustrate it, let us consider an analogy with explanation. To say that some facts taken together fully ground another is akin to say that the former completely explain the latter. To say that some facts partially ground another is like saying that the former provide a partial explanation of the latter. It is customary to define the partial variety in terms of full grounds (Rosen, 2010, p. 115; Audi, 2012, p. 698; Fine, 2012, p. 50; Raven, 2013, p. 194; see also Trogdon & Witmer, 2021).

Completability:

f is a partical ground of g if and only if there is a plurality of facts Γ such that (1) Γ is a full ground of g and (2) f is a member of Γ.

This principle tells us, for example, that if [Hypatia is a philosopher] is a partial ground of [Hypatia is a philosopher and a mathematician], then [Hypatia is a philosopher], on its own or together with other facts, is a full ground of [Hypatia is a philosopher and a mathematician].Footnote 4 In slogan form: partial ground is dichotomous (cf. (Leuenberger, 2020, p. 2565). If something has a partial ground, it has a full ground (see Dixon, 2016a for a more detailed discussion of partial grounds). The Completability principle will be the spotlight of Sect. 6. I shall postpone its discussion for now. But the reader is advised that talk of partial grounds will occasionally appear from the next section on.

2 Nomic approaches to iterated ground

There are five families of approaches to the grounds of grounding facts. Schematically, these views can be classified as follows (the labels are from Bennett, 2017 and Wilson, 2019).

-

(1)

Primitivism (or Fundamentalism): Whenever f grounds g, nothing grounds the fact that f grounds g. (This view does not enjoy popularity.)

-

(2)

Zero-Grounding Account: Whenever f grounds g, the fact that f grounds g is zero-grounded. That is, the fact that f grounds g is ‘the conclusion of an explanatory argument from the empty collection of premisses’ (Litland, 2017, p. 280; see Wallner, 2018 for a critical discussion of this view).Footnote 5

-

(3)

Downward Anti-Primitivism: Whenever f grounds g, the fact that f grounds g is grounded in g. (See Bennett, 2017, pp. 205–206 for a discussion of this view.)

-

(4)

Upward Anti-Primitivism: Whenever f grounds g, the fact that f grounds g is fully grounded in f (Bennett, 2017, pp. 193–198; see Dasgupta, 2014, pp. 572–574 and Wilson, 2018, pp. 594–598 for criticism).

-

(5)

Nomic Approaches or Connectivism: Whenever f grounds g, the fact that f grounds g is partially grounded in some law of ground that facts like f ground facts like g.

Since the minimalist account belongs to the fifth group, let me say more about nomic approaches. These views share the idea that what grounds facts of the form ‘f grounds g’ are general principles connecting f and g. An analogy with causal explanation is apt. As laws of nature link causes and effects, laws of ground join grounds and grounded together. Roughly put, we could say that nomic approaches are motivated by the idea that grounding laws allow us to enjoy unified grounding explanations. Different and superficially diverse grounding facts could be subsumed under a few general principles about what grounds what (for a discussion of what motivates the adoption of a nomic approach, see Schaffer, 2017).

To make things more concrete, let us consider a toy example. Suppose that [Ines loves Nilde] partially grounds [Ines loves Nilde and Ines is a logician]. What grounds the fact that [Ines loves Nilde] grounds [Ines loves Nilde and Ines is a logician]? Nomic approaches would argue that there is a grounding law that conjunctive facts of the form [ϕ & ψ] are partially grounded in each of [ϕ] and [ψ]. Such a law would be a ground of the fact that [Ines loves Nilde] grounds [Ines loves Nilde and Ines is a logician]. Unsurprisingly, more complex cases would require us to invoke more sophisticated grounding laws.Footnote 6

Diversity abounds among nomic approaches. In the literature, we can find: functionalist views (Schaffer, 2017); deductive-nomological models (Wilsch, 2015, Granjer, 2021); primitivist views that invoke a special operator (Glazier, 2016; cf. Fogal & Risberg, 2020); and essentialist views (Dasgupta, 2014; Fine, 2012; Kment, 2014; Lenart, 2021; Rosen, 2010, 2017). This list may well be incomplete. For reasons of space, I cannot reconstruct these views. However, recall that this paper does not aim to establish the superiority of the minimalist account over these competing views. Nor does it aim to establish the correctness of nomic approaches over the other available strategies to answer the question of iterated ground. Instead, the goal is to canvass the general tenability of a minimalist conception of laws of ground, thereby filling an underexplored conceptual space. The result is a profitable expansion of the family of nomic approaches for those in the market for a theory of grounding laws.

As I will explain in the next section, the minimalist account is structurally analogous to Humeanism about natural laws. It is well known that essentialism and Humeanism about laws of nature are philosophical adversaries. Thus, one might reasonably expect that also minimalism and essentialism about the grounding laws will be opposed to one another. As it will become clear in due course, this seems to be the case. Essentialist approaches conceive of grounding laws as general facts that express or capture necessary connections that arise from the nature of their constituents. There are difficult questions regarding the specification of such an essential connection. For example, the “direction” of the essentialist link among some given constituents is unclear. Likewise, it is not immediately obvious whether all the given constituents must be essentially connected to each other. Elucidating these issues is a burden that the essentialist must shoulder. Here a general formulation of the core of essentialism will suffice to clarify the opposition with the minimalist account (see Wallner, 2018, pp. 1269–1270 for a similar formulation):

Essentialism:

Whenever f grounds g, there is a law of ground L that involves the essential connection between some or all constituents of f and g such that L at least partially grounds the fact that f grounds g.

Rosen illustrates the essentialist view with a familiar example. Suppose that [p] grounds [p or q]. On essentialism, [[p] grounds [p or q]] is grounded in [p] and a ‘general grounding law’ such as ‘[◻v∀ϕ∀ψ(ϕ ⊃ ([ϕ] grounds [ϕ v ψ]))]’ (Rosen, 2017, p. 284), where ‘◻v’ is an operator which means something like ‘it lies in the nature of the disjunction that …’. Dasgupta (2014, p. 568) explicitly claims that an essentialist fact of this sort can be understood as a law of ground. And Fine discusses a similar view for truths. Whenever a truth C is grounded in some truths Γ, there is a ‘generalization of the particular connection of ground that will hold in virtue of the nature of’ Γ or ‘the items it (the plurality of facts) involves’ (2012, pp. 75–76).

It goes without saying that essentialist grounding laws are metaphysically necessary. As is now standard, necessity follows from essentiality. To use the previous example, if it lies in the nature of the disjunction that ∀ϕ∀ψ(ϕ ⊃ ([ϕ] grounds [ϕ v ψ])), then it is metaphysically necessary that ∀ϕ∀ψ(ϕ ⊃ ([ϕ] grounds [ϕ v ψ])) (cf. Rosen, 2017, p. 391).

Note that Essentialism should not be confused with the thesis that any essentialist fact is a law of ground. For example, it might be a fact about the essence of {Hypatia} that it has Hypatia as a sole member. But it does not seem right to say that it is a law of ground that the essence of {Hypatia} grounds the fact that this singleton set has Hypatia as a sole member. Such a law lacks sufficient generality, which is the mark of lawhood. By contrast, the principle that for every {x}, the essence of {x} grounds the fact that {x} has x as a sole member is a more plausible candidate grounding law (see Glazier, 2017, pp. 2873–2878 for discussion of when and where grounding and essentialist explanations come apart).

Having clarified essentialism about laws of ground, I turn to articulate the minimalist view.

3 The minimalist account of grounding laws

The minimalist account of grounding laws is structurally analogous to a familiar Humean conception of laws of nature. On the Humean view, natural laws are nothing but universal generalizations that supervene upon the Human mosaic—namely, the contingent distribution of fundamental properties and relations that fundamental things instantiate. Laws thus understood encode and systematize patterns in the mosaic (the classic references are Lewis, 1983, 1994; For discussion, see Lange, 2013, Hicks & van Elswyk, 2015, Marshall, 2015, Miller, 2015, Hicks, 2020, Kovacs, 2020c). In a similar fashion, the minimalist account holds that the grounding laws ultimately supervene on the Humean mosaic, and they are elite systematizations of grounding patterns. In slogan form: no difference in the grounding laws without a corresponding difference in the fundamental tiles of the mosaic.

Some important clarifications are in order. To start, let us note that the structural similarity between the minimalist account and Humeanism is just that, namely a structural similarity. There are significant differences between these approaches. Therefore, we should not conflate the minimalist view with Humeanism. For example, Humean natural laws are classically analyzed in terms of privileged regularities and non-nomic vocabulary. Arguably, a purist Humean account of grounding laws should be ground-free. By contrast, the minimalist account retains the idiom of ground to characterize the grounding laws. It does not aim to analyze away ground from the grounding laws. Another relevant difference is that a typical Humean would happily maintain that natural laws are, metaphysically speaking, non-fundamental. After all, they are derivative upon goings-on in the mosaic. Unlike the Humean, minimalists need not embrace an analogous view about the grounding laws. Supervenience is not ground. The claim that grounding laws ultimately supervene upon facts about the mosaic does not entail, or does not immediately rule out, that there is no ground-theoretic sense in which such laws can be fundamental (for more on ground and supervenience, see Leuenberger 2014a and 2014b, and Chilovi, 2021). This is good news. As I will explain in the next section, there are persuasive reasons for believing in the fundamentality of some grounding laws. It would be a drawback of the view if the minimalist account could not accommodate fundamental grounding laws. Fortunately, I will show that even minimalist grounding laws can be fundamental in a certain ground-theoretic sense. But first, let us continue with the illustration of the minimalist view.

It is common wisdom that not any true generalization is a law. We need a criterion for distinguishing between laws of ground and accidental regularities. Typically, Humeans appeal to the best system account (BSA), which turns laws into elite regularities (Lewis, 1994, pp. 478–480; see also Loewer, 2004 and 2012). A true generalization is a law just in case it figures as a theorem in every true deductive system of facts about the world that achieves, on balance, the best combination of simplicity and informativeness.

Minimalists can embrace BSA, or a suitable adaptation of it, and argue that grounding laws are theorems of every best system that describes the grounding patterns of a world under study. However, they might have to reject a Lewisian constraint: the principle that the non-logical vocabulary of the axioms of the best system must refer only to perfectly natural properties (cf. Lewis, 1983, pp. 366–368). These are properties that carve reality at the joints. They ground objective similarities among things and suffice to characterize everything completely and without redundancy. And, in our world, physics is in the business of discovering them. Charge, mass, and spin are putative examples of perfectly natural properties (Lewis, 1986, pp. 60–61). Lewis proposes the requirement of perfect naturalness to eschew a ‘perverse choice of vocabulary’ (1983, p. 367) that would achieve the simplicity of the best system illegitimately.

The minimalist, however, should not prohibit grounding laws from figuring in the best system just because they are formulated in a vocabulary that does not involve perfectly natural properties only. As it happens, it is a live possibility that some grounding laws do not satisfy the Lewisian constraint of perfect naturalness. The minimalist should not rule them out. Consider, for example, the plausible law that disjunctions are partially grounded in their true disjuncts. It is dubious that being a disjunct is a perfectly natural property. For example, this property does not appear in our best physical theories. Nor does it seem obvious that being a disjunct is a property that grounds objective similarities among things. But even so, the plausibility of this grounding law is not undermined by the absence of perfectly natural properties in its formulation. Now consider the law that the existence of a singleton set is grounded in the existence of its member. Perhaps being a singleton is a property that grounds objective similarities among things. But it is not a property that figures in our best physics. Thus, it remains unclear whether it is a perfectly natural property. But such a possibility does not threaten the apparent plausibility of the singleton law. Nor does it seem to give us a strong reason for banishing this law outright.

The rejection of the naturalness constraint leaves the thorny question of how to legitimately achieve the simplicity of BSA for grounding laws unanswered. However, this is an unsolved problem for laws of nature as well. To mitigate the issue, one could relax the Lewisian principle and maintain that the formulation of laws of ground should contain at least some perfectly natural properties. Alternatively, one could argue that grounding laws must include some perfectly natural properties or some non-perfectly natural yet joint-carving notions. In Siderian fashion, one might call structural notions the ones that best capture the structure of reality (Sider, 2011, 7.2). Then, it could be argued that some structural notions should appear in the formulation of the laws of ground. On this proposal, some mathematical and logical properties can be structural (Sider, 2011, p. 19). To use one of the previous examples, if the property of being a singleton is structural, then the singleton law could satisfy the revised constraint (but note that which mathematical and logical notions are structural properties is a contested affair. For example, see Sider, 2011, 10.2).Footnote 7

It is a challenging task to adjudicate between these options. Arguably, a comprehensive evaluation demands a comparison against the backdrop of a specific metaphysical theory. However, the point here is different: rejecting the naturalness constraint does not amount to a downright insolvable problem.

Setting the above complications aside, we can formulate the core of the minimalist account of grounding laws with these two principles.

Minimalism:

laws of ground are true universal generalizations about what grounds what.

BSA:

a true universal generalization about what grounds what is a law of ground in a possible world w if and only if it is a theorem of every best system that describes the grounding patterns of w.

These tenets can be sharpened further. But additional bells and whistles are negotiable. For present purposes, nothing more is needed. As I will explain in the next section, the problematic principle is Minimalism. For the time being, I will omit the discussion of BSA.

Before motivating this account, it may be instructive to consider a plausible formulation of minimalist grounding laws. For the sake of simplicity, I offer a schema for singular variables. However, the proposal should strictly speaking be generalized to allow for plural variables.Footnote 8 Schematically, a law could be quasi-formally formulated as follows, where the variables P and Q stand for properties or relations. (All the variables should be read as bound. I will suppress some quantifiers for the sake of readability.)

Minimalist Grounding Law:

∀f∀g ((f = [x has some P1, …, PN] & g = [x has some Q1, …, QN]) ⊃ f partially or fully grounds g)

The schema is meant to capture the idea that for any fact f and any fact g, if f is a fact about some constituents such-and-such related and g is a fact about some constituents so-and-so related, then f partially or fully grounds g. Obviously, the difficult part is specifying the constituents of the grounding laws. Two plausible examples will convey the general idea, the first of which deserves the label of paradigm case.Footnote 9

Consider the principle that the existence of an object grounds the existence of its singleton set (e.g., Schaffer, 2009, p. 375). If this were a minimalist grounding law, it would look quasi-formally like this.

Singleton:

∀f∀g ((f = [x exists] & g = [{x} exists] ⊃ f grounds g)

Now suppose that facts about the dispositions of objects are grounded in facts about the non-modal categorical properties they possess playing the role of dispositional or causal basis (cf., Prior et al., 1982). As a law of ground, this principle could be quasi-formally formulated as follows.

Categoricalism:

∀f∀g((g = [x has some disposition D] & f = [x has some categorical property Q that plays the causal basis role of D] ⊃ f grounds g)

Whether Singleton and Categoricalism are true grounding laws is a contentious matter which I shall not attempt to settle. Yet both laws give us an accessible illustration of the minimalist framework outlined so far.

Before presenting some reasons why someone might endorse the minimalist account, I must address a potential worry. We may wonder about the relationship between the minimalist grounding laws and their instances. Like other nomic approaches, the minimalist view would typically accept that the grounding laws ground (at least partially) their instances. However, because of the structural similarity with Humeanism about laws of nature, it might be tempting to believe that minimalist grounding laws are, in turn, grounded in their instances. Despite its naturalness, the temptation must be resisted. As I formulated it, the minimalist account does not dictate any specific view about the relationships between the grounding laws and their instances. To repeat, I proposed that the minimalist account holds that the grounding laws are privileged true generalizations that ultimately supervene on the Humean mosaic. But such a claim does not entail that the instances of the grounding laws ground the latter. Therefore, we should not presuppose that this is the only way minimalist grounding laws and their instances can be related (Rosen, 2017, pp. 287–288 makes a similar point). The proposed framework is thus compatible with different views about the relationship between the grounding laws and their instances. As such, I wish to leave open how specific minimalist views can conceive of it.

Why would anyone endorse the minimalist account of laws of ground? There are two important reasons, in addition to providing a theory of the grounds of grounding facts. Both draw on the structural similarities between the minimalist view and Humeanism about laws of nature.

The first reason appeals to the benefits of a Humean conception of natural laws. For example, Marshall claims that the motivations for embracing Humeanism about laws of nature—such as ‘ideological parsimony and the avoidance of obscure epistemically problematic primitives’ (2015, p. 3157) —extend to a Humean conception of laws of metaphysics. Not all Humeans would agree with Marshall. However, like Humeanism about natural laws, the minimalist account can claim to offer an unmysterious conception of grounding laws as nothing but privileged regularities. Therefore, it suits grounders who are inclined to ‘regard the covering metaphysical laws as being mere regularities’ (Sider, 2011, p. 172).

The second concerns the possibility of contingent laws of ground. A typical motivation for embracing Humeanism about laws of nature is that it leaves room for an alleged desirable contingency. A similar reason can be adduced for minimalism about the grounding laws.Footnote 10 In possible worlds where the patterns of instantiation of fundamental properties (and relations) differ from those of our world, the grounding laws are different. This account is thus an attractive option for the sympathizers of the idea that ground violates a principle of internality which can be standardly formulated as follows (for a discussion on internality and its link to necessitarian views of ground, see Leuenberger 2014a, Skiles, 2015; Richardson, 2019):

Internality

: f fully grounds g ⊃ necessarily((f & g) ⊃ f fully grounds g)

There are independent reasons for believing in contingent ground. For example, one might think that some legal and social facts are only contingently grounded. I currently enjoy legal residency in the UK. This fact is grounded in some facts about the post-Brexit UK legal framework. Before the end of the Brexit transition period, however, I was also a legal UK resident. This fact was grounded in some facts about the pre-Brexit EU legal framework. On the minimalist account, we can explain the persistence of the grounded fact by citing a change in the laws about the grounds of UK residency (see Wilson, 2020, pp. 59–62 for similar cases). Necessitarians should not fear: the claim is not that ground is contingent. Instead, the claim is that the contingency of ground represents a reason someone could invoke in favour of the minimalist account.

As we might have expected, the minimalist account appears to be opposed to essentialism about the grounding laws (as well as other necessitarian nomic approaches). On essentialism, the laws of ground are metaphysically necessary. A law of the form ∀f∀g((f = [x has some P1, …, PN] & g = [x has some Q1, …, QN]) ⊃ f grounds g) would express the essential connection between the constituents of f and g. It should be understood as preceded by the familiar box operator for necessity as in ◻∀f∀g((f = [x has some P1, …, PN] & g = [x has some Q1, …, QN]) ⊃ f grounds g). By contrast, no box should be introduced if this were a minimalist law of ground.

Thus far, I have presented the metaphysical core of the minimalist account. Specific versions will differ on how Minimalism, BSA, and the two schemata of grounding laws are articulated. I will leave these matters open, for they are independent from the purposes of this paper. Instead, I turn to discuss the most intriguing claim that nomic approaches make: namely, that some laws of ground are fundamental. The remainder of the paper discusses the tenability of a minimalist account of fundamental grounding laws.

4 The fundamentality argument

Let us call the Fundamentality Thesis that according to which some laws of ground are fundamental. Such a thesis is appealing for one main reason. The acceptance of the Fundamentality Thesis yields a unified and parsimonious theory. Instead of positing a plethora of fundamental particular grounding facts, we countenance a small number of basic general grounding principles that account for the grounding connections among all other facts. Like fundamental natural laws, fundamental grounding laws are plausible ‘root explanatory principles’ (Schaffer, 2017, p. 316) or satisfying unexplained explainers (cf., Maudlin, 2007, pp. 5–49). A related advantage is that the resulting theory is simpler than one that posits a multitude of particular grounding facts. It allows us to ground many derivative particular facts in some basic fundamental laws of what grounds what.Footnote 11

These benefits vindicate the popularity of the Fundamentality Thesis. For example, Schaffer defends an argument for the conclusion that ‘there are ungrounded facts about the existence’ of laws of ground (2017, p. 315). Echoing this claim, Rosen claims that beyond the domains of the conventional and the quasi-normative, there ‘may be fundamental general norms: rules that simply hold, but not in virtue of anything more fundamental’ (2017, p. 187). He also claims that ‘it’s highly likely that some such facts [the laws of ground] (are) basic in the grounding order’ (Rosen, 2017, p. 288). Similarly, Wilsch appears to be sympathetic to the idea that ‘the laws [of ground] are the independent dynamic postulates that God would have to decree in addition to the instantiation of fundamental properties and relations’ (2015, p. 3307).

More could be said about the Fundamentality Thesis. However, my goal is not to adjudicate its truth. Here my claim is a different one. It seems to me that the above merits represent prima facie cogent reasons for embracing the idea of fundamental laws of ground. Accordingly, we might wonder whether the minimalist account can accommodate the Fundamentality Thesis. If this view cannot establish the fundamentality of some grounding laws, it would be less appealing than other nomic approaches that can do so. As I will argue in the remainder of this paper, the minimalist account can hold that some grounding laws are fundamental. But to accomplish this goal, the minimalist must address a forceful argument, which I outline below, that threatens the viability of fundamental minimalist grounding laws. The good news is that such an argument can be resisted. However, my overall evaluation will not be unreservedly enthusiastic: the fundamentality of minimalist grounding laws has non-negligible theoretical costs that are not clearly outweighed by their benefits.

The combination of Minimalism (Sect. 3) and widely shared principles about ground yields the falsity of the Fundamentality Thesis. I will call this the Fundamentality Argument.

We need three assumptions to get this argument off the ground. These are also useful to avoid unnecessary complications that would distract us from our main target, namely the possibility of fundamental minimalist grounding laws.

First, I assume that laws of ground are facts. Recall that we took that ground relationships occur only among facts—this assumption blocks ‘category mistake’ type of objections from the get-go.

Second, to ease the foregoing discussion, I restrict the focus to positive instances of laws of ground (see Shumener, 2019, p. 801 for a similar restriction on the verifiers of laws of nature). These are facts that involve individuals instantiating the properties and relations that figure in the law of which they are instances. An example will illustrate. Consider a familiar toy law from our philosophy of science classes: ∀x(Fx ⊃ Gx). If this were a law of ground, it would be a fact: [∀x(Fx ⊃ Gx)] (first assumption). A positive instance of this law is a fact like [Fa & Ga], where a is an individual. By contrast, [~ Fa ∨ Ga] is an instance but not a positive one. In effect, the second assumption bars certain logically equivalent facts from being positive instances of laws (for a technical discussion of factual equivalence and ground, see Correia, 2010; Krämer & Roski, 2015; Krämer, 2019).

Lastly, we need to distinguish between the fundamentality of facts and the fundamentality of their constituents. As discussed in Sect. 3, the fundamentality of laws of ground cannot be understood in terms of that of their constituents. The two senses come apart. It might be that some fundamental facts involve only fundamental items. But typically, grounding laws will not as they connect the more fundamental with the derivative. To repeat, I conceive of the fundamentality of facts in terms of Ungroundedness (Sect. 1).

Bearing these assumptions in mind, we can lay out the Fundamentality Argument against a minimalist account of fundamental grounding laws. In its simplest form, it goes like this.

-

(1)

Minimalism: laws of ground are true universal generalizations.

-

(2)

Platitude: true universal generalizations are partially grounded in their instances.

-

(3)

Ungroundedness: a fact is fundamental if and only if it is ungrounded.

From premisses (1) – (3), we reach the conclusion that:

-

(4)

Laws of ground are not fundamental.

If grounding laws are true universal generalizations (about what grounds what), and if these are partially grounded in their instances, they cannot be ungrounded. Therefore, laws of ground are not fundamental either. If sound, the argument establishes the falsity of the Fundamentality Thesis.

The minimalist cannot renounce Minimalism, for this would amount to the rejection of the very view they advocate. If we wish to free the possibility of minimalist grounding laws, either the Platitude or Ungroundedness (or both) must go. In the remainder of this paper, I discuss the denial of these principles and problematize each move.

Two comments are in place before we proceed any further. First, the Fundamentality Argument targets a peculiar audience: minimalists who are persuaded by the serviceability of the Fundamentality Thesis. This argument does not represent a threat to all minimalists. And it does not faze metaphysicians who are ‘inclined to reject fundamental laws of metaphysics’ (Sider, 2011, p. 172). Nor does it affect nomic approaches that are not committed to Minimalism. For example, both Glazier (2016, pp. 23–26) and Rosen (2017, p. 287) explicitly argue against a conception of grounding laws as regularities. But the Fundamentality Argument does target other nomic approaches that embrace Minimalism or something in the vicinity, such as D-N models (Grajner, 2021; Wilsch, 2015).

Second, because of the structural analogy with Humeanism, someone could believe that the minimalist account suffers a familiar circularity objection (Armstrong, 1983; Emery, 2019; Lange, 2013, 2018; Shumener, 2019). Typically, Humean natural laws are said to explain their instances. Like other nomic approaches, minimalists can happily endorse this claim for grounding laws since these ground their instances. But standardly, Humeans also maintain that the instances explain the laws. If minimalist grounding laws explain their instances and the latter explain or ground the former, a circularity will arise. Here we should note two points. The first is that Humeans have put forward creative strategies to break free from the circularity (Hicks, 2020; Hicks & van Elswyk, 2015; Kovacs, 2020c; Loewer, 2012; Marshall, 2015; Miller, 2015). Once suitably amended, some of these are available to defend the minimalist account. The second is that the minimalist account, as I formulated in Sect. 3, does not entail that the instances ground the grounding laws. Though natural, this claim is not mandatory. Different views about the relationships between grounding laws and their instances can be implemented into the minimalist account. For these reasons, I shall not discuss the circularity objection further.

5 Against the platitude

The first strategy to resist the Fundamentality Argument is to deny the Platitude—namely, the claim that true universal generalizations are partially grounded in their instances. It is a ‘platitude’ because such a claim is incorporated into the standard logic of ground. Fine discusses it as one of the ‘obvious rules’ of ground (2012, p. 59). Correia introduces it as a ‘fairly natural suggestion’ (2014, p. 44). Along these lines, Schnieder includes this principle among the ‘standard introduction and elimination rules for the quantifiers’ (2011, p. 459). However, the Platitude should not be confused with the stronger and more problematic principle that universal generalizations are fully grounded in their instances. Technical issues with this version of the principle are well-known. But these can be set aside for they do not concern the weaker version that appears in premise (2) (see Fine, 2012, pp. 60–63 for some problems with the strong principle). Had the Fundamentality Argument involved the strong version, the rejection of the Platitude would have been an obvious and unproblematic move. The denial of the target version of the Platitude gives rise to unwelcome complications. Two of them provide us with reasons to opt for a different approach.

First, the rejection of the Platitude is logically revisionary. It requires us to abandon a widely accepted principle of the logic of ground. This is not to say that such a replacement cannot be found. However, a theoretically conservative approach that evades the challenge of identifying a satisfactory substitute for the Platitude seems preferable.

Second, there is a more serious problem of unexplained generality. Imagine that Alfie is smart, Bertha is smart, and Chan is smart, and that these are all the individuals there are. By endorsing the Platitude, we can argue that each of [Alfie is smart], [Bertha is smart], and [Chan is smart] partially explains the generality of [∀x(x is smart)]. Each of them contributes to an explanation of why all individuals are smart. The denial of the Platitude does not guarantee this explanatory route. Once we reject the Platitude, there might be universal generalizations of the form [∀xFx] that are not grounded in their instances. What could explain the generality of such facts is not immediately apparent. In our example, if this were the case, we could not say that each of [Alfie is smart], [Bertha is smart], and [Chan is smart] partially grounds and thus partially explains [∀x(x is smart)]. It would remain mysterious what explains this generalization. Perhaps the mystery is not downright unsolvable. But a strategy that avoids this issue is preferable.Footnote 12

There is an interesting option that we might pursue. However, I believe it ultimately fails. Yet the failure is instructive because it guides the minimalist to better attempts. The strategy is to replace the Platitude with Totality or something akin.

Totality:

True universal generalizations are grounded in some totality fact about the Humean mosaic.

As I understand them, totality facts are sort of “and that’s all” higher-order facts. That is, they are facts having other facts as constituents. Following a well-developed conception defended by D. M. Armstrong, we can regard totality facts as expressing that some first-order facts are all the first-order facts that obtain (see Leuenberger, 2020, p. 2658 for a similar interpretation). On Armstrong’s view, totality facts involve a totalling or alling relation that relates the first-order facts (Armstrong, 1997, pp. 198–201; Armstrong would think of totality facts as relating states of affairs). For example, if f, g, and h are all the first-order facts that obtain, then a higher-order totality fact t also obtains; t is the fact that f, g, and h obtain, and these are all the first-order facts that obtain. Presumably, the constituents of the relevant totality facts that ground universal generalizations are first-order facts about all the objects there are or all the objects having certain properties there. There might be different ways of spelling out the ‘that’s all’ clause of totality facts. Likewise, there may be different views about the content of the first-order facts constituting a relevant totality fact. I wish to leave these matters open as my concern is with the general strategy, which I outline below.

The minimalist could argue that laws are grounded in some totality fact about the mosaic. A plausible candidate might be the totality fact having as constituents the particular (first-order) facts about the distribution of fundamental properties and relations and things that instantiate them. One might be inclined to claim that the appeal to Totality defuses the threat of the Fundamentality Argument. However, the problem will not fade.Footnote 13

It seems to me that totality facts thusly understood do not float for free since they have first-order facts as constituents. Suppose that the members of a plurality Γ of first-order facts are all the first-order facts that obtain. A totality fact t would also obtain. This connection strongly suggests a dependence of t upon Γ. A natural view of the relationship between Γ and t is that t is at least partially grounded in Γ. After all, t is the (higher-order) fact that all the (first-order) facts in Γ obtain. If this view is correct, the first-order facts that constitute a totality fact are extremely plausible and readily available candidate partial grounds. Accordingly, if laws of ground are grounded in some totality fact, and totality facts are grounded in their composing first-order facts, then the laws are not ungrounded. The conclusion of the Fundamentality Argument strikes again.Footnote 14

Someone could reject this conception of totality facts. For example, one could argue that totality facts need not be always grounded in their constituents. This option is metaphysically intriguing. But two more natural ways of regarding totality facts give us reason to consider them as at least partially grounded in their constituents.

One view is that a totality fact is a ‘vast conjunction’ of first-order facts related by the totalling relation (Armstrong, 1997, p. 198). The other is that a totality fact is a peculiar universal “vast disjunction” of first-order facts (see Fine, 2012, pp. 61–63 for a discussion and rejection of a similar approach).Footnote 15

Both conceptions lead us to the non-fundamentality of the grounding laws. The logic of ground dictates that conjunctions are partially grounded in their conjuncts. If we adopt the first option, a law of ground would be mediately grounded in the conjuncts of the totality fact. The same logic of ground tells us that disjunctions are grounded in their true disjuncts. If we adopt the second conception, a law of ground would be mediately grounded in the true disjuncts of the totality fact. Either way, the law would not be ungrounded.

The appeal to totality facts, at least as I understand them, is unpromising. Perhaps there are other ways to salvage this strategy. I leave the task of showing that these are successful to the sympathizers of totality facts. For now, I turn the attention to a different and more straightforward option to resist the Fundamentality Argument. The attentive reader would note that the failure of the totality fact strategy hinges on the definition of the fundamental as that which is ungrounded. One might thus wonder whether the minimalist ought to concentrate their effort against Ungroundedness.

6 Against ungroundedness

One justification for positing ground in our theorizing is that it enables an analysis of the fundamental as that which is ungrounded. The popularity of such a definition is evidence of the intuitive appeal of this characterization (e.g., Audi, 2012, p. 710; Bennett, 2017, p. 106; Dixon, 2016b, p. 442; Shumener 2017, p. 1; Rosen, 2010, p. 112; Schaffer, 2009, p. 373; Wallner, 2018, p. 5; Leuenberger, 2020, p. 2648). The rejection of Ungroundedness implies the denial of the fruitfulness of this analysis. As it will become clear in this section, this strategy is puzzling for the minimalist who aims to defend the fundamentality of laws of ground.Footnote 16

One problem is that the rejection of Ungroundedness offends against the conceptual economy of the minimalist account. In addition to ground, we need another concept that characterizes the Fundamentality Thesis. Someone might propose that laws of ground are fundamental by virtue of playing an axiomatic role in the best system. This option is intriguing. However, a minimalist account that resists the Fundamentality Argument without severing the tie between ground and fundamentality is preferable by the yardstick of parsimony.

Another problem is that a worrisome methodological tension arises. We are attempting to defend a minimalist account of fundamental grounding laws. Since ground is already part of our toolkit, we can get a characterization of the fundamental for free by accepting Ungroundedness. This package deal has a clear advantage: we can elucidate the Fundamentality Thesis in a desirable unified way. It is not just that this merit is lost, however. There is something suspiciously odd in a view committed to a thesis about the fundamental that accepts ground but denies Ungroundedness.

These undesirable implications count against the denial of premise (3) of the Fundamentality Argument. A more promising strategy is to adopt a different formulation of the fundamentality of grounding laws. Ideally, it should preserve the structural properties of ground and avoid excising its link with fundamentality. The remainder of the paper discusses this manoeuvre. I will argue that its advantages are compelling but whether the strategy succeeds is a more controversial affair.

There are two natural views of the fundamental in terms of ground. One conception is expressed by Ungroundendess. The other takes the fundamental as that which grounds everything else: the ‘all-grounding’. Following Leuenberger, who offers an extensive discussion of the implications of this notion, let us define it as follows (2020, p. 2651).

All-Groundedness:

f is fundamental if and only if it belongs to every grounding base.

A grounding base is the ground-theoretic formulation of the more popular notion of a supervenience base. Informally, a grounding base is a plurality of facts that taken together ground every other fact. All-Groundedness captures the plausible view that the collection of fundamental facts explains everything else. Sticking with Leuenberger’s formulation (ibid.), we can define a grounding base like this.Footnote 17

Grounding Base:

a plurality of facts Γ is a grounding base if and only if for every fact f that does not belong to Γ, there is Γ* such that Γ* ⊆ Γ and Γ* is a ground for f.

In terms of All-Groundedness, some laws of ground would be fundamental in the sense that some of them ‘will be an indispensable part’ of ‘whatever full account of the world we offer’ (Leuenberger, 2020, p. 2651). The minimalist could then reformulate the premisses of the Fundamentality Argument as follows:

-

(1)

Minimalism: laws of ground are true universal generalizations.

-

(2)

Platitude: true universal generalizations are partially grounded in their instances.

-

(3*)

All-groundedness: f is fundamental if and only if it belongs to every grounding base.

From (1) – (3*), it does not immediately follow that laws of ground are not all-grounding. The minimalist could argue that the fundamentality of grounding laws should be therefore understood in terms of All-Groundedness. If this move were successful, a minimalist account of fundamental grounding laws would be home and dry.

The appeal to All-Groundedness is a prima facie attractive strategy. This formulation is logically conservative because it does not require us to reject the structural properties of ground. And since it is a ground-theoretic definition, the approach is conceptually parsimonious and escapes the ideological tension that the rejection of Ungroundedness generates.

Unfortunately for the minimalist, the attraction of this approach wears off because trouble is just around the corner. Leuenberger (2020) shows that Ungroundedness and All-Groundedness are logically equivalent. The proof strikes me as correct. It only demands the irreflexivity of ground and the notion of a Grounding Base, which here we accepted.Footnote 18 It follows that the all-grounding laws should be ungrounded under logical equivalence. The replacement of Ungroundedness with All-Groundedness is nothing but a cosmetic remedy. Because of the Platitude, the alleged all-grounding laws are not ungrounded. And if they are not ungrounded, they are not all-grounding either. Once again, we reach the conclusion of the Fundamentality Argument: laws of ground are not fundamental. The problems with the rejection of the Platitude (Sect. 5) will resurface if we attempt to deny it.

This is not the end of the road, however. Leuenberger (2020, p. 2654) argues that there is a way to prize apart All-Groundedness and Ungroundedness: we can reject the Completability principle (Sect. 1). Recall that this is the principle that if f has a partial ground, it has a full ground.

We need to enrich our apparatus to evaluate this strategy. Adapting the Leuenbergerian terminology, let us say that f is weakly all-grounding if and only if it belongs to every full grounding base. And f is strongly all-grounding if and only if it belongs to every partial grounding base. Complementarily, let us say that f is strongly ungrounded if and only if no Γ is a partial ground of f. And f is weakly ungrounded if and only if no Γ is a full ground of f. Weak all-groundedness is ‘weak’ because membership to every full grounding base is a weaker condition than membership to every partial grounding base. The latter is more elitist than the former. Strong ungroundedness is ‘strong’ because it implies that f lacks even a partial metaphysical explanation (see Leuenberger, 2020, pp. 2654–2655 for a more elaborate discussion of these distinctions).

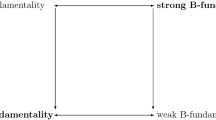

It is a consequence of the logical equivalence between Ungroundedness and All-Groundedness that weak ungroundedness and weak all-groundedness entail each other. So do strong ungroundedness and strong all-groundedness. It also follows that strong all-groundedness entails weak all-groundedness, and strong ungroundedness entails weak ungroundedness.Footnote 19 Under the irreflexivity of ground and Completability, the strong principles entail the respective weak ones. Drawing from Leuenberger (2020, p. 2654), we can construct a diagram that represents a fundamentality square. The arrowheads point to the direction of the entailment (Fig. 1).

In our fundamentality square, weak all-groundedness does not entail strong ungroundedness (instead, the converse is true). An intriguing strategy to resist the Fundamentality Argument emerges.

The minimalist could argue that some laws of ground are weakly all-grounding (and thus weakly ungrounded) without being strongly ungrounded. In essence, this is the view that some grounding laws are fundamental in the sense of being weakly all-grounding and yet are merely partially grounded. The qualifier ‘merely’ is crucial. It means that no plurality of facts Γ is a full ground of such laws. To put it differently, the minimalist should countenance the possibility that some grounding laws are partially grounded in some Γ, but Γ is a mere partial ground. On such a view, the grounds of some fundamental grounding laws are incompletable.

The cost of this approach is the denial of Completability. If we retain this principle, partially grounded laws would be fully grounded in some Γ. Such laws would not be strongly ungrounded. And as inspection of Fig. 1 reveals, they would not be all-grounding either. The rejection of Completability ensures that Ungroundedness and All-Groundedness do not collapse. By giving up Completability, the minimalist could maintain the latter but deny the former to characterize the fundamentality of the grounding laws.

This is all very tantalizing. But the success of this manoeuvre hangs on the plausibility of minimalist fundamental grounding laws that are merely partially grounded. It seems to me that such a view has yet to garner its merits.

To start, it is worth noting that the rejection of Completability can be justified independently from the commitment to the minimalist account of laws of ground. For example, Leuenberger (2020) discusses some compelling metaphysical scenarios which falsify the principle. Echoing this result, Bader (2021) discusses probabilistically grounded facts as plausible examples of facts whose partial grounds are incompletable. For reasons of space, I cannot reconstruct these cases. However, as I explain below, the problem with this strategy is different.

It seems to me that the denial of Completability generates a problematic tension for a minimalist account of the grounding laws. On the one hand, it is undoubtedly desirable to enjoy an unmysterious conception of grounding laws. The minimalist view fares well with this requirement. On the other, we have prima facie reasons for embracing the thesis that some grounding laws are fundamental. The minimalist can acknowledge this claim. But these two things do not harmonize well together. It is one thing to believe that some fundamental facts are merely partially grounded. It is another thing to accept that some fundamental laws are merely partially grounded. The latter claim is in tension with a motivation for adopting the minimalist view, namely that it gives us an unmysterious conception of the grounding laws. To put it in the parlance of metaphysical explanation, we can formulate the problem as follows. Merely partially grounded laws are such that no complete metaphysical explanation of why they hold can be given. These laws cannot be completely explained by facts about the Humean mosaic. Worse yet, there would be nothing in the mosaic (or elsewhere for that matter) that would ground a complete metaphysical explanation of why this or that fundamental grounding law obtains. Thus, the minimalist who desires the benefits of the Fundamentality Thesis (Sect. 4) must pay the price of renouncing, or severely weakening, the advertised merit of their account: weakly minimalist all-grounding laws would suffer an inescapable partial ungroundedness. That is, some aspects of such laws would remain inexorably metaphysically unexplained. The appeal to All-groundedness to recover the Fundamentality Thesis is, therefore, a less promising option for the minimalist than what appearances initially suggest.

Let me stop here for now. I suggested that advocates of nomic approaches, including minimalists, have prima facie reasons for adopting the Fundamentality Thesis. However, the rejection of either the Platitude or Ungroundedness raises significant concerns for a minimalist account that aspires to capture such a thesis. On the bright side, however, the problems discussed do not conclusively establish that the fundamentality of minimalist grounding laws is unattainable. Hope remains: my argument shows that there are costs that need to be paid. The next task is to show that the benefits of the minimalist account outweigh such costs. For example, it should be established that there is something to be gained in accepting that some fundamental regularities are merely partially grounded. Perhaps partial ungroundedness (that is, partial metaphysical inexplicability) is better than full ungroundedness. I leave the challenge of defending this claim to the minimalist grounder who is sympathetic with the account marketed in this paper.Footnote 20

Notes

In this sense, ground is strict. It does not allow f to ground itself. The strict sense is opposed to a weak one, which demands or allows f to ground itself.

How to characterize metaphysical explanation is a complicated affair that I shall not attempt to settle here. For present purposes, it suffices to say that metaphysical explanation is not an epistemic notion. It is independent from contextual and pragmatic factors that affect epistemic achievements such as the production of understanding or intelligibility. For a critical discussion, see Maurin (2019).

Conjunct (1) of Completability is a contraction of ‘the facts that are members of Γ taken together fully ground g’. Note that Γ may contain only f.

Note that Litland (2017) defends the zero-grounding account by assuming a non-factive conception of ground as primitive. A more precise formulation of the schema would be: whenever f factively grounds g, (1) f non-factively grounds g and (2) the fact that f non-factively grounds g is zero-grounded.

Someone might believe that natural laws are ceteris paribus. Do laws of ground require us to specify the absence of undermining factors in their formulation? Some laws, like the one for conjunctive facts, appear to be exceptionless. Perhaps others are not. Grajner (2021, pp. 9–13) argues that we should accept both varieties. For now, we can remain neutral: an answer to this question would demand a case-by-case analysis which cannot be pursued here.

Note, however, that laws of ground do not satisfy the Siderian principle of purity (Sider 2011, 7.2). This says that a fact is pure if and only if it involves only structural notions. Sider takes structural notions to be fundamental or fundamentality-conducive (2011, p. 163). But laws of ground connect the more fundamental with the derivative. Therefore, they do not involve only structural notions. Sider (2020, fn. 6) acknowledges a similar point. For a discussion of derivative entities appearing in metaphysical laws, see Glazier (2016).

To avoid unnecessary complications, I will not show how such a generalization can be achieved.

There are non-Humean contingent views of natural laws. The claim here is not that the minimalist account is the only available contingentist view about the grounding laws.

Since it is possible that grounding chains do not terminate, we should conditionalize these considerations. For example, Schaffer (2017) notes that the Fundamentality Thesis is best understood in conditional form: if grounding chains terminate, then some grounding laws are fundamental. A more ecumenical formulation would be as follows.

Disjunctive Fundamentality Thesis: for every law of ground L, (1) L is fundamental or (2) there is some law of ground L* such that L* partially grounds L.

Under G → MFT, L* is more fundamental than L. The second disjunct ensures that it is laws of ground all the way down if the grounding chain is bottomless.

For a more on the grounds of true universal generalizations, see also Rosen (2010, pp. 117–121).

The appeal to totality facts might raise further worries that are not directly linked to the Fundamentality Thesis. For example, we might wonder whether different true universal generalizations are grounded in the same totality fact. Perhaps, that the same totality fact is a ground for different true universal generalizations might be unproblematic in the same way the same a true disjunct is a ground of different disjunctions. But not all cases might be so unproblematic. Since the discussion of the Fundamentality Thesis does not hang on this issue, I shall set it aside.

As I understand Armstrong’s view, t does not need to be included in Γ. However, someone might wonder whether this conception always generates new facts. For example, we could think that there is a higher-order totality fact t* that totalizes all the totality facts that obtain. Insofar t* is at least partially grounded in some lower-order totality fact, this possibility—albeit odd—does not seem to be metapahsically problematic. The resulting picture would be an upward hierarchy of totality facts grounded in some lower-order ones.

Alternatively, one could follow Armstrong (2004, pp. 72–75) and think of a totality fact as a mereological whole. If we accept that such a whole is constituted by the totalled facts, it seems natural to claim that the constituent facts partially ground the whole. However, this interpretation might be incorrect as parts of mereological wholes need not to constitute them. In response, one could point out that a conception of totality facts as mereological whole so understood generates implausible consequences (see Leuenberger 2020, p. 2659, fn. 21).

There are independent reasons to reject Ungroundedness. For example, Wilson (2014, 2016) and Tahko (2018) argue that it rules out certain live metaphysical possibilities inappropriately—such as the possibility of mutually grounded or self-grounded fundamental entities. It is worth noting that there are other ground-theoretic formulations of fundamentality that claim to mitigate such worries. For example, see Raven (2016), Author (nnnn), and Correia (2021).

It is worth noting that there are other ways to capture the idea of fundamental all-grounding facts.

Here is a reconstruction of Leuenberger’s proof (2020, pp. 2651–2652), adapted to the present notation. Suppose that ground is irreflexive. Then f is ungrounded ↔ f is all-grounding.

Proof → : Suppose that f is not all-grounding. Then there is some grounding base Γ to which f does not belong. It follows that there is Γ* ⊆ Γ and Γ* is a ground for f. Therefore, f is not ungrounded.

← : Suppose that f is not ungrounded. Then there is some Γ that grounds f. Under the assumption that ground is irreflexive, f is not a member of Γ. Now consider the set of all facts Δ. Δ is a grounding base. Pick an arbitrary fact g and consider the set-theoretic difference of Δ and g (written as Δ / g). If f = g, then the Γ ⊆ Δ / f grounds g. If g ≠ f, then g is a member of Δ / f. Since Δ / f is a grounding base, f is not all-grounding for it does not belong to every grounding base.

□

Unsurprisingly, if f belongs to every partial grounding base Γ, then it also belongs to every full grounding base. Under Completability, there are some facts that together with Γ fully ground any other fact that is not included in the base. Fairly obviously, if f lacks any partial ground, it also lacks any full ground.

I am especially grateful to María Pía Méndez Mateluna, Alice Huang, Noelia Iranzo Ribera, Katie Robertson, Franzo Berto, Aroon Cotnoir, Nick Emmerson, Mike Hicks, Markel Kortabarria, Stephan Leuenberger, Al Wilson, Giacomo Giannini, and Martin Glazier. I would also like to thank audiences at the universities of Birmingham, Durham, and St. Andrews, and two supportive reviewers.

References

Armstrong, D. M. (1983). What is a law of nature? Cambridge University Press.

Armstrong, D. M. (1997). A world of states of affairs. Cambridge University Press.

Armstrong, D. M. (2004). Truth and truthmakers. Cambridge University Press.

Audi, P. (2012). Towards a theory of the in-virtue-of relation. The Journal of Philosophy, 109(12), 685–711. https://doi.org/10.5840/jphil20121091232

Bader, R. (2021). The fundamental and the brute. Philosophical Studies, 178(4), 1121–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01486-z

Baron, S., & Norton, J. (2019). Metaphysical explanation: The Kitcher picture. Erkenntnis, 86(1), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-018-00101-2

Beebee, H. & Fisher, A. R. J. (eds.) (2020). Philosophical Letters of David K. Lewis: Volume 1: Causation, Modality, Ontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bennett, K. (2017). Making things up. Oxford University Press.

Berker, S. (2019). The explanatory ambitions of moral principles. Noûs, 53(4), 904–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12246

Chilovi, S. (2021). Grounding entails supervenience. Synthese, 198, 1317–1334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1723-x

Correia, F. (2010). Grounding and Truth-Functions. Logique Et Analyse, 53, 251–279.

Correia, F. (2014). Logical Grounds. Review of Symbolic Logic, 7(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755020313000300

Correia, F. (2021). Fundamentality from grounding trees. Synthese, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03054-2

Dasgupta, S. (2014). The possibility of physicalism. Journal of Philosophy, 111(9/10), 557–592. https://doi.org/10.5840/jphil20141119/1037

Dixon, T. S. (2016a). Grounding and supplementation. Erkenntnis, 81, 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-015-9744-z

Dixon, T. S. (2016b). What is the well-foundedness of grounding? Mind, 125, 439–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzv112

Emery, N. (2019). Laws and their Instances. Philosophical Studies, 176(6), 1535–1561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1077-8

Fine, K. (2012). Guide to ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding (pp. 37–80). Cambridge University Press.

Fogal, D., & Risberg, O. (2020). The metaphysics of moral explanation. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford Studies in Metaethics (Vol. 15, pp. 170–194). Oxford University Press.

Glazier, M. (2016). Laws and the completeness of the fundamental. In M. Jago (Ed.), Reality making (pp. 11–37). Oxford University Press.

Glazier, M. (2017). Essentialist explanation. Philosophical Studies, 174(11), 2871–2889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0815-z

Grajner, M. (2021). Grounding, metaphysical laws, and structure. Analytic Philosophy, Early View. https://doi.org/10.1111/phib.12216

Hicks, M. T. (2020). Breaking the explanatory circle. Philosophical Studies 178 (2), :533–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01444-9

Hicks, M. T., & van Elswyk, P. (2015). Humean laws and circular explanation. Philosophical Studies, 172(2), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0310-3

Jenkins, C. S. (2011). Is metaphysical dependence irreflexive? The Monist, 94, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.5840/monist201194213

Kment, B. (2014). Modality and Explanatory Reasoning. Oxford University Press.

Kovacs, D. M. (2020a). Four questions of iterated grounding. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 101(2), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12591

Kovacs, D. M. (2020b). Metaphysically explanatory unification. Philosophical Studies, 177(6), 1659–1683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01279-z

Kovacs, D. M. (2020c). The oldest solution to the circularity problem for Humeanism about the laws of nature. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02608-0

Krämer, S., Roski, S. (2015). A note on the logic of worldly ground. Thought: A Journal of Philosophy, 4 (1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/tht3.158

Krämer, S. (2019). Ground-theoretic equivalence. Synthese, 198(2), 1643–1683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02154-4

Lange, M. (2013). Grounding, scientific explanation, and humean laws. Philosophical Studies, 164(1), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-012-0001-x

Lange, M. (2018). Transitivity, self-explanation, and the explanatory circularity argument against humean accounts of natural law. Synthese, 195, 1337–1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1274-y

Lenart, K. (2021). Grounding, essence, and contingentism. Philosophia, Early View. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-021-00360-4

Leuenberg, S. (2014). From grounding to supervenience? Erkenntnis, 79(1), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-013-9488-6

Leuenberger, S. (2014). Grounding and necessity. Inquiry, 57(2), 151–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2013.855654

Leuenberger, S. (2020). The fundamental: Ungrounded or all-grounding? Philosophical Studies, 177(9), 2647–2669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01332-x

Lewis, D. (1983). New work for a theory of universals. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 61(4), 343–377.

Lewis, D. (1986). The Plurality of Worlds. Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (1994). Humean supervenience debugged. Mind, 103(412), 473–490.

Litland, J. E. (2017). Grounding ground. In K. Bennett & D. Zimmerman (Eds.), Oxford studies in metaphysics (Vol. 10, pp. 279–315). Oxford University Press.

Loewer, B. (2004). David Lewis’s Humean Theory of Objective Chance. Philosophy of Science 71(5), 1115–1125. 10.0031-8248/2004/7105-0041

Loewer, B. (2012). Two accounts of laws and time. Philosophical Studies, 160(1), 115–37. 10.1007/s 11098-012-9911-x

Marshall, D. (2015). Humean laws and explanation. Philosophical Studies, 172(12), 3145–3165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-015-0462-9

Maudlin, T. (2007). The metaphysics within physics. Oxford University Press.

Maurin, A.-S. (2019). Grounding and metaphysical explanation: It’s complicated. Philosophical Studies, 176, 1573–1594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1080-0

Miller, E. (2015). Humean scientific explanation. Philosophical Studies, 172, 1311–1332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0351-7

Prior, E. W., Pargetter, R., & Jackson, F. (1982). Three theses about dispositions. American Philosophical Quarterly, 19(3), 251–257.

Rabin, G. O. (2018). Grounding orthodoxy and the layered conception. In R. Bliss & G. Priest (Eds.), Reality and its Structure: Essays in Fundamentality (pp. 37–49). Oxford University Press.

Raven, M. J. (2012). In defence of ground. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 90(4), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12220

Raven, M. J. (2013). Is ground a strict partial order? American Philosophical Quarterly, 50, 193–201.

Raven, M. J. (2016). Fundamentality without foundations. Fundamentality without Foundations. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 93, 607–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12200

Richardson, K. (2019). Grounding is necessary and contingent. Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2019.1612777

Rosen, G. (2010). Metaphysical dependence: Grounding and reduction. In B. Hale & A. Hoffmann (Eds.), Modality. Metaphysics, logic, and epistemology (pp. 109–35). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosen, G. (2017). Ground by Law. Philosophical. Issues, 27(1), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/phis.12105

Schaffer, J. (2012). Grounding, transitivity, and contrastivity. In Correia F. & Schnieder B. (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding. Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 122–138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2009). On what grounds what. In D. Manley, D. J. Chalmers, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 347–383). Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2017). Laws for metaphysical grounding. Philosophical. Issues, 27(1), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/phis.12111

Schnieder, B. (2011). A logic for because. Review of Symbolic Logic, 4, 445–465. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1755020311000104

Shumener, E. (2019). Laws of nature, explanation, and semantic circularity. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 70(3), 787–815. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axx020

Sider, T. (2011). Writing the book of the world. Oxford University Press.

Sider, T. (2020). Ground grounded. Philosophical Studies, 177(3), 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1204-6

Skiles, A. (2015). Against grounding necessitarianism. Erkenntnis, 80(4), 717–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-014-9669-y

Author Surname, Author Initial. (XXX). Title, Journal, page range.

Tahko, T. (2018). Fundamentality. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/fundamentality/

Thompson, N. (2019). Questions and answers: Metaphysical explanation and the structure of reality. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 5(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1017/apa.2018.51

Trogdon, K., & Witmer, D. (2021). Full and Partial Grounding. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 7(2), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1017/apa.2020.26

Wallner, M. (2018). The ground of ground, essence, and explanation. Synthese 198 (Suppl 6), 1257–1277. ttps://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1856-y

Wilsch, T. (2015). The nomological account of ground. Philosophical Studies, 172, 3293–3312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-015-0470-9

Wilson, A. (2018). Metaphysical causation. Noûs, 52, 723–751. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12190

Wilson, A. (2019). Review of Making Things Up, by Karen Bennett. Mind, 128(510), 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzy047

Wilson, A. (2020). Classifying dependencies. In D. Glick, G. Darby, & A. Marmodoro (Eds.), The Foundation of Reality: Fundamentality, Space and Time (pp. 46–23). Oxford University Press.

Wilson, J. M. (2014). No work for a theory of grounding. Inquiry, 57, 535–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2014.907542

Wilson, J. M. (2016). The priority and unity arguments for grounding. In K. Aizawa & C. Gillet (Eds.), Scientific Composition and Metaphysical Ground (pp. 171–204). Palgrave-MacMillan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giannotti, J. Fundamentality and minimalist grounding laws. Philos Stud 179, 2993–3017 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-022-01811-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-022-01811-8