Abstract

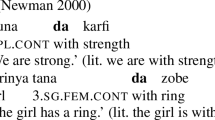

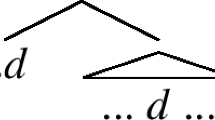

In some sentences, demonstratives can be substituted with definite descriptions without any change in meaning. In light of this, some have maintained that demonstratives are just a type of definite description. However, several theorists have drawn attention to a range of cases where definite descriptions are acceptable, but their demonstrative counterparts are not. Some have tried to account for this data by appealing to presupposition. I argue that such presuppositional approaches are problematic, and present a pragmatic account of the target contrasts. On this approach, demonstratives take two arguments and generally require that the first, covert argument is non-redundant with respect to the second, overt argument. I derive this condition through an economy principle discussed by Schlenker (in: Maier, Bary, Huitink (eds) Proceedings of Sub9, 2005).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, e.g., Kaplan (1989).

I will have little to say about cases where demonstratives are acceptable but their definite counterparts are not, e.g. (8 a)–(8 b). See King (2001) for a more detailed discussion of such cases.

I will also put to one side so-called “emotive” uses of demonstratives, which are often compatible with semantically unique descriptive content, e.g. (19):

Such uses of demonstratives raise puzzles that I cannot address here. See (Wolter 2006) for further discussion.

I do not consider the descriptivist proposals of King (2001), Roberts (2002) or Wolter (2006) in detail in this paper. Elbourne (2008) provides a detailed, critical discussion of both King (2001) and Roberts (2002), so perhaps saying more about them is unnecessary here. But I will add a few brief remarks. Since King ties the denotation of a demonstrative to the speaker’s intentions, it is clear that his theory, as it stands, cannot account for the relevant contrasts [this point is also observed by Nowak (2014, 428, fn. 25)]. For instance, supposing that the speaker has the intention to talk about whoever wrote Blood Meridian, King’s theory cannot explain why (9 b) is unacceptable. However, like Elbourne’s theory, it is not implausible that King’s theory could be supplemented with the sort of pragmatic account that I develop in Sect. 5. As for the accounts of Roberts and Wolter, neither appear to have the empirical reach of Elbourne’s account. More specifically, it is unclear how Roberts could account for cases such as (4). When a demonstrative is not being used deictically [as in (1)] Roberts requires that it has an accompanying linguistic antecedent in discourse (so-called “discourse deictic” demonstratives) (Roberts 2002, 122–123). But the demonstrative in (4) has no accompanying linguistic antecedent. So, in order to handle all of the relevant data, Roberts’s conditions need to be relaxed. One might try to amend her account by allowing that no accompanying linguistic antecedent is needed when the relevant entity is “weakly familiar”: when the existence of the entity referred to is evident to the participants in the discourse, for example by direct perception or deduction from things that have been said, even though it has not been mentioned (Roberts 2002, 24). It is arguable that this amendment would handle a sentence such as (4). However, the observation in fn. 24 below implies that even if my car is weakly familiar in context, (34 b) is infelicitous. As for Wolter, it is unclear how she could account for (3). Wolter works within a framework which assigns predicates situation variables that determine where the predicate is to be evaluated. She requires that the situation variable assigned to the argument of the demonstrative determiner be free in the relevant sentence (Wolter 2006, 64). But quantified cases such as (3) involve binding the situation variable associated with the argument of the determiner. It is unclear how to revise Wolter’s account to solve this problem (also see Sect. 6 for a more general problem with this sort of binding).

What has been presented here is a (harmless) simplification in two respects. First, I assume that the semantic value of the covert variable is a set. But this means that, relative to a context, the covert variable will rigidly designate its value, which is problematic (Stanley and Szabó 2000, 252). For this reason, the semantic value of the variable is better treated as an intensional entity such as a property, rather than a set. Second, in order to handle quantified cases, the covert structure will likely need to be more complex than simply a set/property variable. See (Stanley and Szabó 2000) and (Hawthorne and Manley 2012, ch. 4.5) for further discussion.

As far as I can tell, my account of the target contrasts doesn’t hang on which particular semantics for descriptions we adopt. For instance, we could have chosen a broadly Russellian, quantificational account. See (Coppock and Beaver 2015) for a survey of the various semantics available here.

\(\mathcal {N}\) is not itself a noun-phrase, since it is a complex made up of a noun-phrase and the variable \(\mathcal {V}\). However, given our assumptions above regarding this variable, \(\mathcal {N}\) will have the type of a noun-phrase.

The lambda binder ‘\(\lambda\)’ is a device for forming functions. More specifically, a lambda-term \(\ulcorner \lambda \alpha : \phi . \ \delta \urcorner\) is to be understood as “the smallest function which maps every \(\alpha\) satisfying \(\phi\) to \(\delta\)”. \(\phi\) is the domain condition, and is introduced by a colon; while \(\delta\) is the value description, and is introduced by a period. See (Heim and Kratzer 1998, ch. 2.5) for further discussion.

‘X’ is intended to be a placeholder for a syntactic structure, e.g. a noun-phrase. I have presented things this way because I want to remain neutral on how exactly this argument is represented at logical form.

The condition \(f(x) = 1\) is usually treated as a definedness condition rather than a “mere entailment”, but this won’t make a difference for our purposes.

A similar explanation can be be given for the unacceptability of demonstratives involving superlatives, such as (11 b) (‘That fastest horse won the race’) from Sect. 1. This result is obtained if, e.g., \(\ulcorner \hbox {fastest } {F }\urcorner\) holds of an individual x just in case x is the fastest thing to which F applies (so that \(\ulcorner \hbox {fastest } {F }\urcorner\) denotes, at most, a singleton). The result is also obtained if a more sophisticated entry for superlatives is used, e.g. that given by Herdan and Sharvit (2006) (see fn. 38 for further discussion).

Although intuitions about these matters are rather delicate, I take the initial motivation for maintaining that non-redundancy is a constraint on definedness rather than a “mere entailment” to be the feeling that nothing is “said” when this condition is not satisfied (but see the arguments immediately below).

On Nowak’s account, the covert argument is the second argument to the determiner, rather than the first. Although this difference is significant when it comes to demonstratives that feature postnominal modifiers (see Sect. 5.3), it isn’t relevant when we restrict our focus to the target contrasts. Moreover, presenting things as in (29) will be more convenient when it comes to discussing my preferred account in Sect. 5.2.

It is worth mentioning that Nowak does not provide an account of implicit content; nor does he explicitly discuss what role implicit content plays with respect to the non-redundancy condition. However, some of his remarks suggest that it is contextually enriched overt predicate material that forms the second argument of the determiner. This is as what we are assuming here. Whether Nowak would endorse all of our assumptions outlined in Sect. 2.1 is unclear, but they do appear to be compatible with his general framework.

Presuppositions that are not satisfied by the context set can sometimes be “accommodated”, e.g. even if it is not common knowledge that I have a sister I can say ‘I’m visiting my sister this weekend’. However, I take it that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to accommodate a presupposition once the speaker has signaled their ignorance as to whether the presupposition is satisfied.

Interestingly, as Schoubye (2011, 160, fn. 6) notes, examples such as (31 a)–(31 c) are improved when the second conjunct is embedded in the antecedent of a conditional:

(32)

(a)

I don’t know if France is a monarchy, but if the King of France is bald, then...

(b)

I don’t know if Mary ever smoked, but if Mary stopped smoking, then...

Why there should be this contrast is unclear. Schoubye suggests that the contrast marker ‘but’ license “local accommodation” here so that the antecedent is interpreted at a possible world where the presupposition is satisfied. Whatever the correct explanation of this fact is, accommodation doesn’t seem to be available in (31 a)–(31 c).

Hawthorne and Manley also maintain that covert material supplied by the covert variable must be salient. This is supposed to explain the contrast between (34 a) and (34 b) when both are uttered discourse initially and without any associated demonstrations:

(34)

(a)

I took the car to the garage last night.

(a)

I took ?? that car to the garage last night (Hawthorne and Manley 2012, 209).

Even if the audience can exploit a background assumption that the speaker has only one car, if no car is salient then there will be no salient covert material to restrict the denotation of the overt noun-phrase ‘car’. In this case, (34 b) is predicted to be infelicitous.

Note that in each case we can make the covert material as salient as we like, e.g. by pointing to the relevant objects—this makes no difference to (un)acceptability.

In fairness to Hawthorne and Manley, after giving their account they say ‘no doubt this sketch is inadequate’ (Hawthorne and Manley 2012, 209).

Thanks to both Cian Dorr and Philippe Schlenker for independently drawing my attention to (Schlenker 2005) and the principle of Minimize Restrictors!

My formulation of Minimize Restrictors! varies slightly from Schlenker’s, but as far as I can tell these differences are not significant.

There is clearly much more to be said about condition (ii). For instance, even if ‘stupid’ has an expressive function, ‘The stupid only student is angry’ is still unacceptable. See (Blumberg 2018) for further discussion of this issue. Also see (Marty 2017) for a more general discussion of condition (ii).

One might think that Minimize Restrictors! could be derived from the sort of general redundancy principles that have been discussed by Fox (2007); Singh (2011); Mayr and Romoli (2016); and Blumberg (2017). For instance, these authors appeal to principles such as the following: \(\phi\) cannot be used in context C if \(\phi\) and \(\psi\) have the same assertive content relative to C, and \(\psi\) is a simplification of \(\phi\) (\(\psi\) is a simplification of \(\phi\) if \(\psi\) can be derived from \(\phi\) by replacing nodes in \(\phi\) with their subconstituents). Assertive strength is commonly defined as follows: clauses F and F’ have the same assertive content relative to C just in case \(\{ w: F' \ \text {is \,true \,in} \ w \} = \{ w: F \ \text {is \,true \,in} \ w \}\). However, although (36 a) is a simplification of (36 b), even if is not commonly known that the American president is educated, (36 b) is infelicitous. That is, (36 a) and (36 b) need not have the same assertive content relative to C in order for (36 b) to be infelicitous. [See (Blumberg 2018) for some reasons why, in this case, the infelicity can’t be explained by simply maintaining that the presuppositions of (36 b) aren’t satisfied.]

For a similar reason, Minimize Restrictors! cannot be derived from the principle of Maximize Presupposition (Heim 1991; Percus 2006; Schlenker 2012): if a sentence S is a presuppositional alternative of a sentence S’ and the context C is such that (i) the presuppositions of S and S’ are satisfied in C; (ii) S and S’ have the same assertive content relative to C; and (iii) S carries a stronger presupposition than S, then S should be preferred to S’ [this formulation is due to Schlenker (2012, 393)]. As Marty (2017) points out, \(\ulcorner \hbox {the } B \urcorner\) does not trigger stronger presuppositions than \(\ulcorner \hbox {the } A B \urcorner\). Presuppositional strength is commonly defined as follows: a clause F carries a stronger presupposition than a clause F’ just in case \(\{ w: F' \ \text {is \,undefined \,in} \ w \} \subsetneq \{ w: F \ \text {is \,undefined \,in} \ w \}\). But now consider a world w with the following features: \(|A_{w}| = 0\), \(|B_{w}| = 1\). At w, the presupposition triggered by \(\ulcorner \hbox {the } B \urcorner\) will be satisfied, but the presupposition triggered by \(\ulcorner \hbox {the } A B \urcorner\) will not be.

Marty (2017, ch. 3) tries to derive a principle similar to Minimize Restrictors! from a more general theory of implicatures. However, in order to predict that (36 b) is infelicitous in context, he requires that (36 b) and (36 a) be contextually equivalent. But as noted above, this isn’t necessary for (36 b) to be unacceptable. (Also see fn. 41 for further discussion of Marty’s attempt to derive Minimize Restrictors!.) I suspect that Minimize Restrictors! is partly the product of a principle recently discussed by Anvari (2018) called “Logical Integrity”, for this would explain why \(\ulcorner \hbox {the } A B \hbox { is } G \urcorner\) is infelicitous even when it isn’t contextually equivalent to \(\ulcorner \hbox {the } B \hbox { is } G \urcorner\). However, this still leaves condition (ii) of Minimize Restrictors! unaccounted for. See (Blumberg 2018) for further discussion of this topic.

To be sure, use of a demonstrative does often communicate the stronger claim that it is commonly believed that F does not denote a singleton. What this shows is that inferences based on the Competition Principle are often strengthened through an “epistemic step” where from ‘not B P’ one infers ‘B not P’, where B is a belief operator. A similar effect has been observed for scalar implicatures (Sauerland 2004), for so-called “antipresuppositions” (Chemla 2007), and for general redundancy-based inferences (Blumberg 2017). I am hopeful that the explanation for the epistemic step for antipresuppositions presented in (Chemla 2007) can be applied to the Competition Principle, but this matter requires a more detailed investigation.

As a reviewer observes, the phenomenon of interest carries over to the plural case as well:

(41)

[Mary has pictures of all Olympic 100m gold medalists and Olympic 200m gold medalists.]

(a)

The 100m gold medalists look fitter than the 200m gold medalists.

(b)

Those 100m gold medalists look fitter than ?? those 200m gold medalists.

As the reviewer notes, my account can explain such contrasts so long as we replace the definite’s uniqueness presupposition with a maximality presupposition (Sharvy 1980).

Thanks to Ben Holguín for discussing this worry with me and inspiring this example.

Note that the felicity of both (44 a) and (44 b) poses a problem for Hawthorne and Manley’s account presented in Sect. 4.2, given the principle Maximize Presupposition: among a set of competitors whose logical forms have the same assertive content relative to the context, choose the one that marks the strongest presupposition (see fn. 30 for a more detailed presentation of this principle). On Hawthorne and Manley’s account the presuppositions of demonstratives are stronger than the presuppositions of definite descriptions. On this theory, felicitous use of a definite description presupposes that it is “candidly” restricted to a singleton, i.e. that ‘the audience can grasp how a quantified expression is being restricted without having to access it in a way that is cognitively parasitic on that very use of the expression’ (Hawthorne and Manley 2012, 140). As Hawthorne and Manley (2012, 210) point out, the non-redundancy condition on demonstratives is just a refined candidness condition: if the audience is in a position to grasp how the demonstrative is being restricted using salient supplemental information, then clearly the audience is able to non-parasitically grasp how the demonstrative is being restricted. Thus, Maximize Presupposition says that (44 b) should be preferred. However, as we have seen, (44 a) is perfectly felicitous.

These cases are the definite and demonstrative counterparts of sentences such as (47):

(47)

Every boy who danced with a girl kissed her.

Such constructions pose the following problem: the pronoun clearly isn’t referring to any particular girl, and familiar ways of interpreting it as a variable bound by ‘a girl’ don’t give the right truth-conditions. Put another way, the choice of girl seems to co-vary with the choice of boy, but it is unclear how this reading is achieved given standard binding principles. The literature on this topic is enormous: see (King and Lewis 2016) for a survey; (Abbott 2002) contains a discussion of donkey demonstratives in particular.

In order to make these ideas precise, the covert structure that provides implicit content will need to be more complex than simply a set variable. See fn. 13.

A reviewer suggests that even demonstratives that feature superlatives are acceptable when they take donkey anaphoric readings:

(48)

Every race organizer praised the fastest horse (in his race) and the jockey who mounted that fastest horse.

This seems to raise the following problem: if ‘fastest horse’ invariably denotes a singleton (supposing it denotes anything at all), then appealing to shifts in the value of the variable that provides implicit content can’t explain why (48) is unproblematic. However, cases such as (48) can be accounted for if an independently motivated entry for superlatives is adopted, namely that of Herdan and Sharvit (2006). On this semantics, superlatives have a context sensitive meaning that allows, e.g. ‘fastest horse’ to denote the set of horses each of which are fastest in their respective race. That is, on this semantics ‘fastest horse’ needn’t denote a singleton. We can then argue that the superlative denotes a singleton when it appears on the definite in (48) (e.g. the singleton containing the unique fastest horse in the relevant race), but does not denote a singleton when it appears on the demonstrative in (48) (e.g. the set of horses each of which is fastest in their respective races). In this case, there is no problem for the Competition Principle.

As Wolter (2006) observes, a similar contrast arises with free choice ‘any’:

(52)

(a)

?? Any man didn’t eat dinner.

(b)

Any man who saw the fly in the food didn’t eat dinner (Dayal 1998, 434–435).

An ‘any’ phrase can become acceptable when modified by a subordinate clause, e.g. a relative clause—a phenomenon known as subtrigging (Dayal 1998, 434).

It is worth noting that Marty’s (2017) theory might be able to explain why postnominal modifiers are able to disrupt the functioning of Minimize Restrictors!. Marty essentially derives Minimize Restrictors! from the presence of a covert exhaustification operator. It is commonly maintained that this operator is sensitive to the syntactic structure of its complement (Katzir 2007). More specifically, the set of relevant alternatives is determined syntactically. It is plausible that when postnominal modifiers are present, the set of alternatives is affected in such a way that the relevant non-uniqueness effects no longer arise. If this is correct, then our observations above would constitute a striking argument in favor of Marty’s account (and accounts that try to derive Minimize Restrictors! through exhaustification more generally). See Blumberg (2018) for further discussion.

In response to contrasts such as (49 a)–(49 b), Nowak (2018) maintains that in some cases involving postnominal modification the modifier may be attached high in the syntactic tree [adopting the proposal of Bach and Cooper (1978)], so that the modifier takes the place of what is usually the covert argument and the head noun takes the place of what is usually the overt argument. This handles examples such as (49 b), since the head noun ‘man’ does not denote a singleton without help from the relative clause ‘who is tallest among Germans’.

However, there are problems with this response. For one thing, the sort of movement it posits is not possible on dominant theories of the syntax of postnominal modification (Bhatt 2002). Moreover, this response still can’t handle cases such as the following:

(53)

Most avid snow skiers remember that first black diamond run they attempted to ski (King 2001, 10).

Relative to a snow skier x, ‘first’ needs to take as argument ‘black diamond run x attempted to ski’—the head noun can’t be separated from the rest of the clause. Finally, adopting a non-standard syntax for postnominal modifiers does not explain the contrast between (51 a) and (51 b): attaching the modifier high in the syntactic tree doesn’t alter the interpretation of definite descriptions. However, it is plausible that the contrast between (51 a)–(51 b) and (50 a)–(50 b) should be accounted for in the same way.

Hawthorne and Manley briefly consider the problem of postnominal modifiers and maintain that these modifiers should count as supplemental and automatically salient, and that what matters is whether the head noun denotes a singleton. That is, the proposal is that felicitous use of a demonstrative presupposes that the head noun does not denote a singleton without help from additional material (either covert material or a postnominal modifier), and that this additional material is salient. But notice that this response leads to further problems with the principle of Maximize Presupposition. If relative clauses are supplemental and automatically salient, then Maximize Presupposition predicts that sentences such as (49 c) should be unacceptable, since (49 b) involves stronger presuppositions because it contains a demonstrative. Thus, Maximize Presupposition says that (49 b) should be preferred. However, (49 c) is perfectly felicitous.

What is given is a simplification of Elbourne’s entry, since he works in a situation semantics where each type is ‘raised’ by an intensional parameter, e.g. the type of a noun-phrase is \(\langle se, st \rangle\) rather than \(\langle e, t \rangle\). See (Elbourne 2008, 429–430) for the details, and see below for a potential problem with trying to reconcile Elbourne’s situation semantics with the pragmatic mechanism presented in Sect. 5.

Notice that on this account it is the index, and not the denotation of the demonstrative that determines the distal feature. This is in order to account for cases such as the following (Nunberg 1993, 23). Suppose I point to two sample plates in my china shop. The first one is right in front of me, but the second is across the room. I say:

(56)

These [I gesture at the nearby plate] are over at the warehouse, but those [I gesture at the distant plate] I have in stock here.

If the denotations and not the indices of ‘these’ and ‘those’ were what was relevant here, then I should have used the one where I used the other.

Elbourne (2008, 434–435) uses a system that involves assigning situation pronouns to predicates, and captures the rigidity of deictically used demonstratives by appealing to an operator that shifts the assigned situation pronoun to the actual world.

Thanks to Cian Dorr for discussion here.

A similar problem arises with cases of donkey anaphoric demonstratives, e.g. (46 b) (‘Every boy who danced with a girl kissed that girl’).

References

Abbott, B. (2002). Donkey demonstratives. Natural Language Semantics, 10(4), 285–298.

Anvari, A. (2018). Logical integrity: From maximize presupposition! to mismatching implicatures. lingbuzz/003866.

Bach, E., & Cooper, R. (1978). The NP-S analysis of relative clauses and compositional semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy, 2(1), 145–150.

Bhatt, R. (2002). The raising analysis of relative clauses: Evidence from adjectival modification. Natural Language Semantics, 10(1), 43–90.

Blumberg, K. (2017). Ignorance implicatures and non-doxastic attitude verbs. In Cremers, A., van Gessel, T., & Roelofsen, F. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 21st Amsterdam colloquium (pp. 135–145).

Blumberg, K. (2018). A note on deriving minimize restrictors!. New York City: New York University.

Chemla, E. (2007). An epistemic step for anti-presuppositions. Journal of Semantics, 25(2), 141–173.

Coppock, E., & Beaver, D. (2012). Weak uniqueness: The only difference between definites and indefinites. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 22, 527–544.

Coppock, E., & Beaver, D. (2015). Definiteness and determinacy. Linguistics and Philosophy, 38(5), 377–435.

Dayal, V. (1998). “Any” as inherently modal. Linguistics and Philosophy, 21(5), 433–476.

Elbourne, P. (2005). Situations and individuals. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Elbourne, P. (2008). Demonstratives as individual concepts. Linguistics and Philosophy, 31(4), 409–466.

Elbourne, P. (2013). Definite descriptions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fox, D. (2007). Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In U. Sauerland & P. Stateva (Eds.), Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics (pp. 71–120). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hawthorne, J., & Manley, D. (2012). The reference book. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heim, I. (1990). E-type pronouns and donkey anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy, 13(2), 137–77.

Heim, I. (1991). Artikel und definitheit. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Handbuch der semantik. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Heim, I., & Kratzer, A. (1998). Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Herdan, S., & Sharvit, Y. (2006). Definite and nondefinite superlatives and NPI licensing. Syntax, 9(1), 1–31.

Kaplan, D. (1989). Demonstratives. In J. Almog, J. Perry, & H. Wettstein (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan (pp. 481–563). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Katzir, R. (2007). Structurally-defined alternatives. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(6), 669–690.

King, J. C. (2001). Complex demonstratives: A quantificational account. Cambridge: MIT Press.

King, J. C., & Lewis, K. S. (2016). Anaphora. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (summer 2016 ed.). Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Lakoff, R. (1974). Remarks on ‘this’ and ‘that’. In Proceedings of the Chicago Linguistics Society (Vol. 10, pp. 345–356).

Levinson, S. (1998). Minimization and conversational inference. In A. Kasher (Ed.), Pragmatics (Vol. 4, pp. 545–614). London: Routledge.

Marty, P. (2017). Implicatures in the DP domain. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Mayr, C., & Romoli, J. (2016). A puzzle for theories of redundancy: Exhaustification, incrementality, and the notion of local context. Semantics and Pragmatics, 9(7), 1–48.

Mikkelsen, L. (2004). Specifying who: On the structure, meaning, and use of specificational copular clauses. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Nowak, E. (2014). Demonstratives without rigidity or ambiguity. Linguistics and Philosophy, 37(5), 409–436.

Nowak, E. (2015). Complex demonstratives, hidden arguments, and presupposition. Unpublished manuscript.

Nowak, E. (2018). Saying ‘thatF’is saying whichF: Complex demonstratives, hidden arguments, and presupposition. Unpublished manuscript.

Nunberg, G. (1993). Indexicality and deixis. Linguistics and Philosophy, 16(1), 1–43.

Percus, O. (2000). Constraints on some other variables in syntax. Natural Language Semantics, 8(3), 173–229.

Percus, O. (2006). Antipresuppositions. In Ueyama, A. (Ed.), Theoretical and empirical studies of reference and anaphora: Toward the establishment of generative grammar as an empirical science. Report of the Grant-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Project No. 15320052, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Roberts, C. (2002). Demonstratives as definites. In K. van Deemter & R. Kibble (Eds.), Information sharing: Rand presupposition in language generation and interpretation (pp. 89–196). Stanford: CSLI Press.

Sauerland, U. (2004). Scalar implicatures in complex sentences. Linguistics and Philosophy, 27(3), 367–391.

Schlenker, P. (2005). Minimize restrictors! (Notes on definite descriptions, condition cand epithets). In Maier, E., Bary, C., & Huitink, J. (Eds.), Proceedings of Sub9.

Schlenker, P. (2008). Be articulate: A pragmatic theory of presupposition projection. Theoretical Linguistics, 34(3), 157–212.

Schlenker, P. (2009). Local contexts. Semantics and Pragmatics, 2(3), 1–78.

Schlenker, P. (2012). Maximize presupposition and Gricean reasoning. Natural Language Semantics, 20(4), 391–429.

Schoubye, A. J. (2011). On denoting. Ph.D. thesis, University of St Andrews.

Sharvy, R. (1980). A more general theory of definite descriptions. Philosophical Review, 89(4), 607–624.

Singh, R. (2011). Maximize presupposition! and local contexts. Natural Language Semantics, 19(2), 149–168.

Soames, S. (1986). Incomplete definite descriptions. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 27(3), 349–375.

Stalnaker, R. (1978). Assertion. Syntax and semantics (Vol. 9, pp. 315–332). New York: Academic Press.

Stanley, J., & Szabó, Z. G. (2000). On quantifier domain restriction. Mind and Language, 15(2–3), 219–261.

Stanley, J. C. (2002). Nominal restriction. In G. Peter & G. Preyer (Eds.), Logical form and language (pp. 365–390). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Westerståhl, D. (1985). Determiners and context sets. In J. van Benthem & A. ter Meulen (Eds.), Generalized quantifiers in natural language (pp. 45–71). Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Wolter, L. (2006). That’s that: The semantics and pragmatics of demonstrative noun phrases. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Yalcin, S. (2014). Semantics and metasemantics in the context of generative grammar. In A. Burgess & B. Sherman (Eds.), Metasemantics: New essays on the foundations of meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

Versions of this paper were presented at a department colloquium at the University of the Witwatersrand, at a meeting of the junior reading group at Institut Jean Nicod, and at a semantics seminar run by Philippe Schlenker. I would like to thank all of the participants at those presentations for their feedback. Thanks to Chris Barker, Manuel Križ, Murali Ramachandran, Daniel Rothschild and Yael Sharvit for helpful discussion of various points. Also, Ben Holguín, Ethan Nowak, James Pryor, Stephen Schiffer and Philippe Schlenker provided useful comments on earlier drafts. Finally, I would especially like to thank Cian Dorr for his continued encouragement, and for providing valuable feedback at every stage of the project’s development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blumberg, K.H. Demonstratives, definite descriptions and non-redundancy. Philos Stud 177, 39–64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1179-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1179-3