Abstract

Descriptive Experience Sampling (DES) attempts to apprehend in high fidelity pristine inner experience (the naturally-occurring, directly-apprehended phenomena that fill our waking lives, including inner speaking, visual imagery, sensory awarenesses, etc.). Previous DES investigations had shown individual differences in the frequency of inner speaking ranging from nearly zero to nearly 100% of the time. In early 2020, the Internet was ablaze with comments expressing astonishment that constant internal monologue was not universal. We invited Lena, a university student who believed she had constant internal monologue, to participate in a DES analog of a pre-registered study: We would announce, on the Internet, that we would conduct a fully transparent DES investigation and roll out videos of the DES interviews (and annotated transcripts) as they occurred in (almost) real-time, something like “reality TV about inner experience,” so that spectators could examine for themselves our characterizations of Lena and how we arrived at them. We describe here the procedure and its findings: Lena did not have frequent internal monologue (contrary to her expectations); she did have frequent visual imagery (to her surprise); and we speculated about the frequent presence of two simultaneous “centers of gravity” of her experience. The entire procedure is available for inspection.

Similar content being viewed by others

On January 27, 2020, a twitter user with the handle @KylePlantEmoji tweeted a “fun fact”: “Some people have an internal narrative and some don’t.” In a blog post spawned by that tweet, Ryan Langdon, a Physician Assistant student, quipped,

My day was completely ruined yesterday when I stumbled upon a fun fact that absolutely obliterated my mind. I saw this tweet yesterday that said that not everyone has an internal monologue in their head. All my life, I could hear my voice in my head and speak in full sentences as if I was talking out loud. I thought everyone experienced this. (Langdon 2020)

Ryan’s post went viral, garnering (at the time of this writing) more than 7,500,000 views and 2,500 comments, many of which were the commenters’ descriptions of their own inner experiences (most referring to internal monologue, some not). For example, “Robin” wrote,

I always have words running through my mind, whether it’s me conversing with myself, thinking of my next move, or a word someone says suddenly making a song start playing in my mind, I always hear things.

“MaEva,” wrote,

I do have a constant inner narrative, but can’t talk directly with myself in my head, so my mind has to make up someone [sic] talk with. Most of the time it’s an actual person that I know in real life, or someone I don’t but anyway I can imagine the way they would answer.

In contrast, “Ella” wrote,

Just when you thought things couldn’t get worse. I don’t hear sounds in my head, not even when I am trying to remember a song, I also can’t imagine images so there are no pictures in there either. I often joke when someone asks what I’m thinking about that there’s nothing going on upstairs, just blank.

There are two important observations to make from this viral event: (1) many people are fascinated by the topic of inner experience; and (2) many people are intensely confident about the characteristics of their own inner experience.

1 Pristine Inner Experience

The internal-monologue-kerfuffle comments such as those just cited are claims about what Hurlburt (2011a; Hurlburt & Akhter, 2006) has called “pristine inner experience,” the naturally-occurring, directly apprehendable “before the footlights of consciousness” (James, 1890) phenomena that we create for ourselves and in which we are immersed every waking moment of our lives. When Ryan wrote “my voice in my head,” he was describing a directly apprehended imaginary inner voice speaking “in full sentences as if I was talking out loud,” and thus was intending to characterize his own pristine inner experiences.

Pristine experiences are not just verbal but include any directly apprehended (before the footlights of consciousness) phenomenon either internal (e.g., innerly visualizing the scene I am reading about; feeling a stomach cramp) or external (e.g., hearing a train pass; noticing the grid-like pattern of my windowpane). Pristine experiences can be tightly tied to the physical surroundings, as when I feel the toothbrush bristle slide between my two front teeth; but they can also be far distant from the present physicality, as when, while brushing my teeth, I imaginarily see my friend’s look of surprise at last week’s birthday party.

My pristine experience is that which, at some particular moment, I make figural out of the welter of a nearly infinite range of potential figures: While brushing at 7:14:27 am, I might feel the particular bristle, or recall my friend’s face, or hear the water running, or feel the pressure in my left foot, or rehearse what to say at my upcoming meeting, or notice the particular turquoise-y blue of the toothpaste drip, or try to remember who was at the 1945 Potsdam Conference, or any of millions of other potential experiences. Perhaps just one of those occurs at a given moment; perhaps two or a few (but not all of them) occur simultaneously. Or perhaps none—perhaps at 7:14:27 I am entirely on autopilot, implementing some skillful toothbrushing script without directly apprehending anything before the footlights of my consciousness.

There is nothing hidden, implied, concealed, unconscious, or obscure about pristine inner experience—it is experientially there at a particular moment, created by me, for me, in my way, directly apprehended as ongoing (Hurlburt, 2011a). It is private and not in any way inferable from external observation: No currently known behavioral or physiological measurement can discover what passes before the footlights of my consciousness as I brush.

“Pristine” refers to naturally occurring, “in the wild.” A psychological experiment whose instructions say, “Form an image of the house in which you grew up” is not an inquiry into pristine imagery. An experiment that says “Pay particular attention to your left foot” is not an inquiry into pristine sensation. An armchair introspection (I will pay attention to whatever arises now) is not an inquiry into pristine experience.

Ryan’s “all my life, I could hear my voice in my head and speak in full sentences as if I was talking out loud” is a claim about his pristine inner experience. It is made with unquestioned confidence and, in fact, with great distress at the possibility that not everyone’s experience is similar to his. Many of the thousands of commenters to Ryan’s blog expressed similar confidence about their own pristine experience, as when Robin wrote, “I always have words running through my mind” or MaeEva wrote, “I do have a constant internal monologue.” And how could they be doubted? They spend their entire waking lives immersed in their own pristine inner experience.

2 Descriptive Experience Sampling (DES)

However, Hurlburt (2011a; Hurlburt & Heavey, 2015) has argued that people typically do not know well the characteristics of their pristine inner experience and are sometimes (maybe often) dramatically mistaken about them. Hurlburt’s claim is based on more than 40 years of Descriptive Experience Sampling (DES) research intending to describe pristine inner experience with fidelity (Hurlburt, 1990, 1993, 2011a; Hurlburt & Heavey, 2006). DES uses a random-interval beeper to cue people to attend to the inner experience that was ongoing at the “last undisturbed moment” before the beep and then engages them in an “expositional interview” aimed at (a) describing each beeped experience with fidelity and (b) ratcheting up the participant’s skill at apprehending and describing experience (through “on-the-job” training, which DES calls “iterative”; Hurlburt, 2009, 2011a) so that future beeped experiences might be apprehended and described with even greater fidelity.

The DES procedure is described in the Method section below. Table 1 lists places where DES has been compared to other methods. To summarize:

-

DES aims at pristine experience—it seeks to describe directly apprehended phenomena, whereas other methods may seek to discover the human significance of events. For example, what van Manen (2016) calls the “experience of ‘being sick in bed’” (p. 64, emphasis added) is the human significance of being sick in bed, not the directly-before-the-footlights-of-consciousness pristine experience that might occur while sick in bed.

-

DES seeks to grasp what is already grasped, whereas other methods seek to bring into view something that was not necessarily originally in plain sight. For example, Petitmengin’s micro-phenomenology (Petitmengin et al., 2018) seeks to make the pre-reflective reflective—to make thematic that which was previously hidden. The phenomena of interest to DES have not been hidden—they were already directly apprehended at the moment the beep interrupts. DES is necessary not because phenomena are hidden (or pre-reflective) but because, on retrospection, they are quickly forgotten (like a dream upon waking) or confused with not-directly-experienced things.

-

DES seeks to describe whatever pristine experience happens to be occurring at the moment of some randomly-triggered beep, whereas most other methods specify their target phenomenon in advance. For examples, Giorgi (1975) specified that his interest was in learning by initiating his interview with “Could you describe in as much detail as possible a situation in which learning occurred for you?” (Giorgi, 1975, p. 84, emphasis added); Petitmengin and colleagues specified that their interest was in pre-seizure phenomena by asking patients with epilepsy to “choose a particular seizure from the past for which the patient retains a memory. If the patient sometimes feels warning sensations, we choose a seizure in which these sensations were especially vivid” (Petitmengin et al., 2006, emphasis added). By contrast, DES asks, “What, if anything, was in your experience at the moment of the beep?” DES refers to this as an “open-beginninged” question (it does not at the outset specify the target content) whereas Giorgi’s and Petitmengin et al.’s questions are closed-beginninged (Giorgi’s began with learning; Petitmengin’s began with a vivid seizure).

-

DES seeks to minimize retrospection. The participant’s task is, within a second or fractions thereof, to “capture” the a-second-ago ongoing experience; then, within a few seconds, to jot down notes constrained by that experience; and then, within 24 h, to participate in an expositional interview constrained by the notes. (We have sometimes minimized the 24-h interval by, for example, following the person around in the natural environment and conducting the interview immediately after the beep; our sense is that this doesn’t matter much). Many other methods inquire about long-past events (such as Giorgi’s “situation in which learning occurred” or Petitmengin’s vivid seizure).

-

DES accepts that most people are not skilled at apprehending their ongoing inner experience and that most people quickly forget their experience or confuse it with not-directly-experienced things. Therefore, DES recognizes that it has to teach its participants the apprehend-and-jot-down and description skills; it does so with “iterative” on-the-job training. DES therefore routinely discards first-sampling-day samples as being unskilled and expects that fidelity is likely to increase across sampling days. Thus, DES descriptions are based on a series of ever-newly-encountered phenomena that are apprehended with (perhaps) ever-increasing skill and described with (perhaps) ever increasing fidelity. Moreover, DES recognizes that, because they have never been asked to do so before and because they have never had experiences other than their own, people may not be skilled at describing the details of their experiential phenomena. Therefore, an approximately hour-long interview follows each sampling period in which skilled DES investigators (who have seen experience samples from dozens or hundreds of people other than themselves) help participants to describe their experiences with fidelity.

-

DES tries to bracket presuppositions about inner experience, that is, to cultivate in DES participants and interviewers a neutral perspective regarding all aspects of inner experience including the existence of any particular characteristic such as internal monologue (Hurlburt & Schwitzgebel, 2007, 2011).

3 A “Pre-registered” Case Study

Lena, an undergraduate student at the university where Hurlburt usually conducts his DES research, was captivated by the Internet internal-monologue kerfuffle. Like many of those commenters, she read Ryan’s blog post and confidently agreed that she, too, has a constant internal monologue, a voice narrating in her head. When she mentioned the kerfuffle in a neuroscience class she was taking, her instructor encouraged her to contact Hurlburt. On February 3, 2020, she did so and expressed interest in participating in a DES study.

Hurlburt suggested that they undertake a DES-case-study analogue of a pre-registered research study. Across the last decade or so, psychological science has increasingly recognized the risks of making the publication of scientific results dependent on their “aesthetics” (particularly their statistical significance or P value) rather than their authenticity (Hardwicke & Ioannidis, 2018). One way to lessen that risk is to “pre-register” research: to describe the rationale, hypotheses, methods and proposed analyses prior to data collection and to make publication decisions based on that prior-to-data-collection description rather than on the actually obtained results. Such a procedure would reduce the incentive to “P-hack” (to continue collecting data until a particular criterion, e.g., P < 0.05, is met) and would lessen the bias against reporting null results. Hurlburt’s suggested case-study pre-registration analogue would be to announce to the world that we would conduct a DES investigation of Lena’s inner experience and would report our results regardless of their outcome—that is, regardless of whether they confirmed Lena’s self-understanding of ubiquitous internal monologue or were in line with Hurlburt’s claim that people often do not know the characteristics of their own inner experience.

Actually, we would be even more thoroughly transparent than pre-registration typically requires. The typical pre-registered research is hidden from view between the registration and the publication—that is, the consumer does not get to verify by direct observation whether the procedures were actually followed and the data actually collected as the pre-registration specified. Hurlburt was suggesting to Lena that we make our entire set of interactions public. Hurlburt would create a website (called “Reality TV about inner experience”; Hurlburt & Krumm, 2020) that announced the upcoming DES investigation of Lena, which (like most DES investigations) would involve at least four DES interviews. We would videotape each interview and roll it out on YouTube before the next interview occurred. Thus, there could be no question of cherry-picking or hiding results—everything would be plainly available as it unfolded.

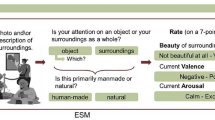

This everything-on-public-display suggestion involved a substantial invasion of Lena’s privacy, so Hurlburt suggested four safeguards. First, Lena should take a few days to consider whether she really wanted to participate in such a public investigation of her private experience and to consult with relatives or friends or whomever she trusted to give her advice on such things. Second, Hurlburt would not release any videos until after the second interview, thus giving Lena a few chances to experience the actual DES procedure before publication ensued. Third, Hurlburt would initially make each YouTube video “unlisted,” giving Lena a chance to review it and potentially veto publication; when Lena approved, Hurlburt would move the video to “public” status. Fourth, Lena could withdraw from the project at any time without having to state a reason and without prejudice. None of those potentials caused Lena to object to anything in any of the videos—the videos were released uncut and unedited on schedule as they occurred. A screen shot from one of the videos is shown in Fig. 1.

Thus, Lena’s sampling was, in most ways, a prototypical case study of DES, though it differed in one fundamentally important way: We took it as an opportunity to present a look inside the DES process as it unfolds, something potentially instructive to those who are fascinated by inner experience both on the Internet and in the scientific community. Furthermore, DES claims that iterative training improves fidelity of apprehending, and presenting the entire set of interviews would allow the viewers to evaluate that claim for themselves. Though Hurlburt and colleagues have over the years made available video clips, transcripts of interviews, and written summaries (e.g., Hurlburt & Heavey, 2006; Hurlburt, 2011a, 2020), they have never before made available an entire set of interviews from start-to-finish in (almost) real time (nor has anyone else, as far as we know). Moreover, published descriptions by DES or other methods are always written retrospectively, from the perspective of reviewing the entire set of data. The present procedure involved transcripts and comments written contemporaneously, allowing the viewer to see if or how concepts evolved across the interviews.

See Table 2 for a summary of several aspects of the evolution of this project, including the webpage containing links to all of Lena’s sampling interview videos and transcripts with commentary. The “Reality TV about inner experience” website and its videos remain as they were when originally created—that is, we have not gone back and edited or cleaned them up (except to fix obvious mistakes such as mis-identifying a speaker in a transcript)—so the reader may vicariously experience the original events as they occurred. [Part II of the “Reality TV about Inner Experience” project repeated the above-described procedure with Ryan Langdon, the author of the blog post that sparked the Internet kerfuffle and our sampling with Lena. Part III repeats the procedure with Sadie Dingfelder, a Washington Post reporter who has written about face-blindness, a condition that she herself says she has. The present paper discusses only Part I.]

4 Method

We engaged Lena in the typical DES sampling procedure: DES typically involves multiple interviewers, so (with Lena’s assent) RTH invited one of his graduate students, Alek Krumm, to participate in the project. We gave Lena the standard DES beeper and earphone (see Interview 1 (DES introduction), 5:58; in Table 2, see Part I: Lena for links) and asked her to wear them on each sampling day until she had collected six samples (requiring approximately three hours) while going about her everyday life. The beeper is programmed to emit a 700-Hz signal randomly, uniformly distributed in the range from a few seconds to 60 min with a mean of 30 min. We instructed Lena that, when the beep sounds, she was to pay attention to whatever was ongoing the “microsecond before” (Interview 1, 6:20) the beep sounded (i.e., the experience that was “caught in flight” by the beep) and to jot down notes about each experience.Footnote 1 The notes were Lena’s “own property” (i.e., the investigators would not themselves read them) to be used by Lena as memory aids in the expositional interview which would follow within 24 h of each sampling period.

DES expositional interviews have two aims: (a) apprehending and describing each of a participant’s beeped experiences in high fidelity; and (b) iteratively improving the participant’s and interviewers’ skills. The (a) apprehending / describing aim involves asking one fundamental question, “What, if anything, was in your direct experience at the moment the beep interrupted you?” (Interview 1, 36:00) and clarifying the ensuing responses. DES interviews are usually in-person and indeed were in person with Lena at the outset. However, due to coronavirus-related limitations, the interviews moved (beginning with Interview 7) to Skype or Zoom. All interviews were video recorded, as is typical in DES. After each interview, AK wrote summaries of Lena’s beeped experiences and circulated those summaries to RTH for tracked-changed edits, comments, and any other queries or exercises that seemed to advance the understanding of Lena’s experience or the interviewers’ skills. These were passed back and forth until both agreed with what had been written about that sampling day. RTH prepared a word-for-word transcript of each interview, and RTH and AK annotated that transcript with commentary that they deemed of potential value to anyone with an interest in DES (in Table 2, see Part I: Lena for links). All videos and annotated transcripts are available on the Internet (see Table 2).

We completed this natural-environment-sampling-followed-by-expositional-interview-followed-by-contemporaneous-written-summaries-and-annotated-transcript procedure 11 times total. Our original agreement had been for Lena to participate in about four or more sampling days, but that we would continue sampling if we found the process interesting, enjoyable, and/or potentially informative for our audiences.

5 Results and Discussion

Spoiler alert

What follows will describe what we found and how we found it. Readers who wish to encounter the interviews as they unfolded, unencumbered by the ex post perspective described here, may wish to explore the website (see Table 2) now.

5.1 Internal monologue: Correcting a misperception

Lena was initially drawn to DES by her interest in internal monologueFootnote 2 and her belief that such monologue was ubiquitous in her own inner experience (Interview 1 (DES introduction), 1:01). However, as with all DES studies, her sampling was not specifically focused on internal monologue or any other particular phenomenon but aspired to be an “open-beginninged” procedure, meaning that, beyond grasping Lena’s inner experience in as high fidelity as we could muster, we had no a priori interest in Lena’s sampling results. If by sampling with Lena we would discover the details of what she called internal monologue, that would have been great. If by sampling with Lena we would discover details of her preoccupation with visions of Egyptian pyramids, that would have been equally great. Had we discovered a preoccupation with left-foot sensations, that would be equally great. Our interest was only and always in Lena’s inner experience—whatever that may involve.

Excluding sampling day 1 as training (as is usual in DES studies), we discussed 37 samples across 10 sampling days, of which 7 samples involved innerly speaking or innerly hearing words (19%). All 7 of these involved innerly spoken or heard words synchronized to reading or typing.Footnote 3 Lena was not surprised to find such inner-speaking-while-reading experiences, but such experiences are not what Lena herself (as well as Ryan and Ryan-blog commentators) described as inner-narration / running-commentary-style “internal monologue.” Therefore, our sampling found zero examples of internal monologue as Lena herself defined it, even though, prior to sampling, Lena understood such experiences as being ubiquitous for her. Note that the discrepancy between expected-ubiquity and zero-samples cannot be understood as being merely a difference in definition of the phenomenon—it was Lena’s definition in both situations.

We discussed 2 samples on Lena’s first sampling day (see Interview 2 (DES sampling day 1) beginning at 4:35 and at 27:45); Lena mentioned the occurrence of inner-narration style internal monologue in both of these samples. The interviewers asked about the details of this monologue, but Lena could not provide any; for example, she could not recall the words of this narration/monologue (see, for example, Interview 2 (DES sampling day 1) 43:25 to 50:07). We wrote a contemporaneous comment into the transcript at 50:07: “Note that we have not discouraged Lena from telling us about her narrative. On the contrary, we have expressed interest and asked for its details.” That is, we conveyed to Lena that if she had internal monologue, we wanted to know its specifics.

Recall that DES customarily discards sampling-day-1 samples as being training because DES participants, on the first day, do not limit themselves to describing inner experience that had been occurring at the moment of the beep and do not generally adequately discriminate between actual ongoing experience and presuppositions or supposed generalizations about experience. Of the samples that DES discards because the participant is unskilled, Lena was 2 for 2 discussing internal monologue.

On days 2 through 11, Lena described zero instances of internal monologue; that is, Lena had 100% internal monologue on day 1 but 0% internal monologue on subsequent days. There are at least three possible explanations: (1) Lena’s experience on day 1 was different from all the remaining days; (2) the interviewers overtly or covertly discouraged Lena from reporting internal monologue; or (3) Lena came to realize that her experience did not in fact include internal monologue. We believe that (1) is unlikely, but if true, it contradicts Lena’s original understanding of her ubiquitous internal monologue. We believe that (2) is not the case; as we just saw, we expressed honest interest in all aspects of her experience and encouraged Lena on future sampling days to report her internal monologue. The “pre-registered” nature of this study allows the readers to evaluate the interviews for themselves: for the internal monologue discussion in sample 1.1, see Interview 2 (DES sampling day 1), 19:47 to 27:47; for the internal monologue discussion in sample 1.2, see 42:53 to 50:09.

That leaves option (3), which we think is correct. That is, we think Lena herself came to believe that she had been mistaken about her internal monologue; see Interview 5 (DES sampling day 4), 47:35 to 53:03, including 47:57 at which Lena says,

You know, it's funny ‘cause I know I started out saying that [referencing RTH’s 47:35 “I have words all the time”], which I feel that I do have words a lot. But I'm also realizing I'm very visual. And in that, in that particular thing, um, I wasn't personally having words. I was taking the words from my environment and creating a mental picture, a play almost.

We encourage readers to evaluate for themselves the believability of Lena’s change in belief. We ourselves find it quite compelling and note the remarkable power that careful discussions of 37 randomly selected moments had for Lena, causing her to abandon a lifelong and strongly held belief about her own inner experience.

5.2 Inner seeing: Recognizing the overlooked

Lena was innerly seeing (aka seeing an image) in 20 of the 37 samples discussed (54%).Footnote 4 That was a surprise to Lena—she had not considered herself a particularly visual person (recall Interview 5 just quoted, as well as Interview 6 (Lena asks questions), 0:40 to 2:14). By DES standards, 54% is a very large frequency of any phenomenon.

Nine of Lena’s 20 inner seeings occurred while she was reading. In fact, in nearly all of the samples while she was reading (9 of 11 while-reading samples), Lena created some sort of inner visual illustration of the text. For example, at sample 6.2, Lena was reading a textbook about how people’s circadian rhythms change as they become older. As she read, Lena innerly saw an elderly man watering the plants in his outdoor garden with a hose. The seeing was clear and in color—she saw a tall man with white hair, seen from the left side, holding a hose in his right hand. The lighting suggested it was early morning, an apparent illustration of the fact she was reading about—that older adults’ changing circadian rhythms lead to earlier waking (Interview 8 (DES sampling day 6) 21:20 to 27:50).

Lena’s inner seeings ranged in clarity, from very clear (like the man watering) to nearly indeterminate. For example, at sample 8.5, she was trying to remember the parts of the ear. She innerly saw her own drawing of an ear that she had previously sketched for a class, which was appearing to her in this moment only as colors (purple, red, and black). Her interest was not primarily in the colors (that is, this was not a sensory awareness as DES defines that phenomenon; Hurlburt et al., 2009)—it’s just that the colors were the only thing present to her at this moment (Interview 10 (DES sampling day 8) 13:41 to 24:06)—the shapes of the colors (which represented the ear itself) were indeterminate.

Lena’s inner seeings sometimes involved aspects that would be impossible in the real physical world. For example, at sample 8.3, Lena was driving and listening to Scottish bagpipe music. At the moment of the beep, she imagined herself as if she lived in Celtic clan times; she innerly saw herself wearing traditional Scottish belt, tartan shawl, and dress. She simultaneously saw herself from two different perspectives—her face from the front and her body from straight on (Interview 10, 35:11 to 41:13). Such multiple perspectives would be impossible in real seeing.

Throughout her interviews, Lena was confident and differentiated when describing her inner visual experience. That is, she demonstrated (sample by sample) an apparent familiarity with the visual aspect of her experience even though she had not (prior to sampling) considered herself a particularly visual person.

5.3 Sensing: Exploring the unknown

We have illustrated that DES can relatively easily discover that phenomena Lena thought to be frequent are probably actually rare, and that phenomena Lena thought to be rare are probably actually frequent. Those conclusions had become apparent within the first few sampling days. There is a sense in which this paper would be stronger if it ended here, having confidently presented compelling and surprising (at least to some) results. However, DES has the potential to explore less obvious experiential phenomena, and Lena’s interviews provide the opportunity to “ride along” on one such exploration. The results will not be as clear-cut or compelling, but the insights to be gained about how the struggle for fidelity develops over time may be at least as valuable as the clear-cut/compelling results. If your interest is in process, then buckle in and work your way through sampling days 4 through 11.

In interview 4, the DES investigator is trying to understand what Lena is trying to describe about her inner experience. There are two “tryings” involved: Lena is trying to put into words a phenomenon that she has (probably) never tried to describe. We are trying to sort through whether Lena is describing a phenomenon (something directly present to her but difficult to describe) or whether she has perhaps been captured by her own words and presuppositions. It is a struggle on both sides, a struggle that requires each side to clarify and re-clarify for each other the words we use and the intentions behind those words.

We invite you to watch the complete interview for sample 4.1 (see Interview 5 (DES sampling day 4) beginning at 2:34). Here are some snippets of what Lena says there; your task is to try to figure out what experience, if any, she is describing:

3:30 I was, um, visualizing myself performing that song in my philosophy class [laughs].

3:54 So I just kind of imagined singing that song, not like to her but like with her and this sort of camaraderie of the subjects we’ve been discussing.

4:46 So in my mind, I am seeing myself (I’m learning how to play the acoustic guitar) um playing this song on the acoustic guitar in my philosophy class.

5:05 So I see my teacher and, um, I see her as enjoying it as much as I do. And also the, my fellow peers.

5:26 I kind of go back and forth between viewing the whole scene—kind of like how I did with the nurse’s station [a reference to sample 3.1], just having this bird's eye view—and then I go into also feeling myself and viewing it from this perspective, looking down at myself doing the guitar. And I also can back away and then see. So it's like an in and out of that kind of perspective.

[RTH asks “And in and out or simultaneous? And if it’s not simultaneous, can you, do you know, at the moment of the beep, which of these scenes you’re in?”]

6:00 At the moment of the beep, I was in the scene of visualizing myself playing the guitar and saying the words of the song. But yet at the same time, I’m still imagining my teacher here and then students here [gestures]. Um, so I, yeah, I guess I’m seeing it from looking out this way, teacher here, students here and then the layout of the classroom.

6:47 I see myself playing the guitar from, as Lena. But then there’s also this sense of also seeing Lena from outside of myself as well. It, it’s hard to explain as if it’s, it feels like it’s a very wish-washy experience. Like I am not specifically just in the as-Lena, I’m also outside of Lena, too. Um, it’s like, um, mixture of, so I can get like the whole detail of what I’m visualizing.

8:13 I see it in both ways, both perspectives as, as myself playing as I see myself just right now. Like if I had a guitar on my lap, that’s how I'm seeing it [demonstrates looking down at a guitar]. And then I also at the same time, it feels like I can see myself like almost a little bit outside of myself. Almost standing halfway outside of myself and, and getting a different perspective of myself playing the guitar.

9:17 And it’s visually I am in myself and there is that feeling that I’m having a hard time differentiating if, Did I step outside of myself and my visual representation? Or was I just in myself? Like I know I was seeing myself playing the guitar like as this version here. [indicates the first-person perspective looking down on the guitar] But I also didn’t feel exactly myself because I’m not those exact things that I was imagining or fantasizing about.

This was Lena’s fourth sampling day, and it was difficult or impossible to grok what was in her experience at the moment of the beep. Was she clear about what is the exact moment of the beep? Did she understand the difference between simultaneous and sequential? Did she have one image or two? What did Lena mean by “this sense of also seeing Lena from outside of myself” (6:57)? She was consistent in that regard: She said “halfway outside myself” at 8:13 and then seemed to be describing the same thing 60 s later (“Did I step outside of myself and my visual representation?” 9:17), so these were not merely random utterances. It seemed that she was trying to describe something—but what?

It turns out that the key to answering that question seemed to be understanding Lena’s use of the word “sense” (as at 6:47). On the tenth sampling day, we had started to believe that we knew what she meant (but that was only after she used, on the first nine days, “sense” or “sensing” 69 times, not counting “sensation” and not counting expressions such as “does that make sense?”). We came to believe that Lena was indeed using “sensing” to describe a specific experiential phenomenon. Her use of “sensing” was skillful; it was not merely a sloppy or imprecise way of speaking; “sensing” is somewhat vague and circumscribed because the experiences themselves were somewhat vague and circumscribed.

Lena’s sensing, as we eventually came to understand it, involved experiences that were “folded back” on themselves and involved multiple “centers of gravity” of experience wherein one center of gravity was Lena’s direct experiencing in a straightforward way of some internal or external perception (a thought or feeling, for example) and the other center of gravity was Lena’s separate but simultaneous deep / superordinate sense / awareness / contemplation. Lena used “sensing” to refer both to some kind of deep processing and the knowledge that the deep processing was ongoing.

For example, at sample 11.4, Lena was on the phone with her brother talking about consciousness, but she wasn’t paying much attention to her brother. Instead, she was both pondering how bodily injury and disease can impact consciousness (a fairly straightforward thinking, a cognitive/analytical process without explicit words or images) and sensing what it must be like for someone who is so tragically injured that they lose the function of consciousness (a deeply empathic process). As we came to understand it, there were two “centers of gravity” in her experience, which we illustrate in the sketch of Fig. 2.

One center of gravity (on the left in the sketch) was Lena’s thinking in a fairly straightforward way about damage or illness preventing the function of consciousness. The second center of gravity (on the right) was Lena’s empathically entering into the what’s-the-point? / defeated feeling of one who has been deprived of consciousness due to injury or disease. This empathic Lena-center-of-gravity feels herself deeply involved in the why? of the injured person’s world. The Lena-straightforward-center-of-gravity “senses” the existence of the empathic center of gravity but does not empathically enter into it. That is, the experienced defeat was not a characteristic of the straightforward Lena center of gravity; Lena (in the straightforward center of gravity) did not (directly) feel defeated; rather, she sensed that she was feeling defeated.

This distinction between feeling and sensing that she was feeling was difficult for Lena to describe and for us all jointly to understand because simple questions provoked complicated answers. Was Lena feeling (empathically) defeated? Yes (from the empathic-center-of-gravity point of view) but No (from the straightforward-point-of-view). Was Lena sensing a feeling of defeat? Yes (from the straightforward-point-of-view) but No (from the empathic-center-of-gravity point of view). We had to learn what we were talking about at the same time that Lena had to learn what she was talking about and how to talk about it, all of which required practice and refinement. In her own words, see Interview 13 (DES sampling day 11):

33:59 Um, it’s kind of the same of what I said before in the past. Like that sensing / wondering thing where I am deeply sensing, wondering about the question that I have. And to me in this particular moment, it does have a very cognitive, mental um, tone to it. Um, and emotionally what’s there is if consciousness, if you, if, if the damaged body or sick body or whatever doesn’t get to have consciousness, then it was the, I had the feeling of like, uh, it’s hard to explain. Like it was like a feeling like, um, thinking that, yeah, I dunno how to explain the feeling part, but it was, it was like, I don’t know how to explain it. Maybe you have a question that will kind of pry it open a little bit. But there was a feeling about it, there was also this cognitive mental thing about it and this feeling about it. But I don’t, I don’t know how to describe the feeling about it.

An iterative-across-sampling-days process is a necessary predecessor for a comment such as “the same of what I said before in the past,” and such a process provides Lena with the means to describe an experience without necessarily having apt words for it. The opportunity to describe before the words have been clearly defined is a necessary part of the effort to describe in high fidelity: words are created to lie comfortably on experiences, rather than experiences being forced into predefined worded categories. Lena (like most people) had never considered in a differentiated, principled way the features of her pristine inner experience and therefore, she (like most people) was not naturally skilled at doing so. However, she became more skilled through the DES iterative procedure as evidenced, for example, by the evolution and clarification of our understanding of the sensing phenomenon between the guitar-playing sample 4.1 and this injured-person sample 11.4.

So what about Lena’s experience at sample 4.1? We can’t really be sure, because Lena and we were not at that time ready to describe the sensing phenomenon efficiently. But now, with the hindsight advantage of 11 interviews, it seems that “this sense of also seeing Lena from outside of myself as well” referred to a second center of gravity centering around an empathic understanding of her teacher’s reaction in an audience role. From the standpoint of one center of gravity, Lena saw herself looking down at her guitar from the point of view of Lena the guitar player; and from another center of gravity, she empathically understood her singing as being appreciated by her teacher.

6 Discussion

We have tried, in our analog to a pre-registered study, to lay bare fundamental aspects of the DES procedure. In so doing, some things became straightforwardly empirically clear: Prior to sampling, Lena believed she had frequent internal monologue whereas sampling revealed she was mistaken in that belief; sampling revealed that Lena experienced frequent inner visualizations, a characteristic she had overlooked prior to sampling. The case of Lena is thus one more example of the general principle that people are often mistaken, and sometimes dramatically mistaken, about the nature of their own inner experience (Hurlburt, 2011a, b, c).

What to make of Lena’s frequent references to “sensing” is not so straightforward. The DES task is to allow our perspective on Lena’s use of “sensing” (and all other terms) to emerge, triangulated across multiple samples and multiple occasions. By considering the emergence of our perspective on sensing / multiple foci of experience, we have illustrated important aspects of the DES process:

1) The DES procedure is open-beginninged: We did not set out to discover multiple foci of experience. Imagine that Lena had volunteered for a Giorgi-like or micro-phenomenological-like study on internal monologue and participated in an interview that began (echoing Giorgi, 1975), “Could you describe in as much detail as possible a situation in which internal monologue occurred for you?” We suspect that Lena’s self-understanding in such a study would have been similar to her self-understanding during our own first sampling interview, where she reported internal monologue as occurring in both of the two samples we discussed. On that basis, we think it likely that Lena would have created plausible and perhaps even correct characterizations of her own internal monologue but would likely not have come to the realization that such monologue was rare for her. Moreover, she likely would have continued to overlook imagery as a phenomenon that is actually quite frequent for her and she likely would have never discovered her multiple-centers-of-gravity experience.

2) The DES iterative procedure is patient: We tried to understand what Lena was trying to tell us about her experience, and where we didn’t understand, we kept that ball in the air, so to speak, which, thanks to the pre-registered nature of this study, is clearly documented (for example in this comment we made in the contemporaneously written transcript of Lena’s fifth sampling day:

The comprehension / meditative / thoughtfulness / feeling / sensing that Lena is describing is indeed difficult. Is this a directly-before-the-footlights-of-consciousness experience, as Lena has consistently maintained throughout this interview (starting at about 22:08)? Or is it a non-experienced self-theoretical presupposition: if I’m writing I must be experiencing the meaning? It is not our job to try to decide which of these (if either) should be accepted. Instead, we will let the iterative method work: If this kind of experiencing is indeed important, we will likely see it on some subsequent sampling day, and at that time we will have under our belt the practice of talking about this sample. Here, our task is to keep both (or all) possibilities open. (Interview 7 (DES sampling day 5), 28:17)

3) The DES iterative process is forward-looking: We did not, for example, specifically guide any interview back to sample 4.1 in a repetitive attempt to understand or flesh out Lena’s sample-4.1 experience—we had one chance at 4.1 and were ill-prepared to understand it when that chance presented itself. There was no trying to relive or recreate that experience.

4) The DES iterative process is refreshed by new opportunities: Our understanding of samples 4.1 and 6.2, and so on, were doubtless corrupted by our ignorances, presuppositions, and the idiosyncratic peculiarities of each individual sample. Maybe the details of 4.1 apply only to samples where Lena is innerly playing the guitar. Maybe the details of 6.2 apply only to samples where Lena is thinking about circadian rhythms. At each individual interview, we don’t and can’t know which aspects reflect our own presuppositions, or which reflect the specific context, or which are recurring themes—those are balls that have to be kept in the air. But across multiple samples and multiple sampling days, the particular-sample idiosyncrasies will fall away, allowing a common thread to emerge across samples. Here, for example, we came to believe that Lena sometimes experienced multiple centers of gravity. The DES iterative procedure refreshes the exploration with ever new perspectives, allowing triangulation again and again across very different experiences.Footnote 5 Here, for example, we extracted the multiple-centers-of-gravity commonality not merely from one deep dive into one (injured-person) sample, but from an APA-writing-style experience (sample 2.2), guitar playing experience (4.1), Epicurus typing 5.2, stomach pain (5.3), spooky TV (6.3), sexual predation (7.1, 7.2 and 7.3), Celtic life (8.2), distressed neighbor (8.4), daughter crying (8.6), people lying (9.1), nomad wandering (9.2), Hitler empathy (9.3), googling “exilic” (9.4), disciplining toddler (10.1), searching for chords (10.2), cleaning freezer (10.3), “please hold” (10.4), and serious injury in (11.4). Prior to sampling, there would have been no way to predict that from these disparate experiences would emerge a commonality.

5) The DES procedure can be retroactively clarifying. Whereas we did not specifically return to sample 4.1 (see #3), we did naturally come to a refined understanding of sample 4.1 as the result of the encountering of new samples (see #4).

6) The DES procedure is descriptive: We leave “center of gravity” as a descriptive expression without making any neurological, multiple-personality, or any other claims of meaning or causation.

7) DES resists (part of the bracketing of presuppositions) presuming that the phenomena it encounters are similar to (or different from) those described by others. For example, some, perhaps struck by the similarity of terminology, would encourage us to assimilate Lena’s “sensing” to Gendlin’s “felt sense” (Gendlin, 1978/2007). However, Gendlin’s felt sense is a bodily experience, typically brought into existence by a special kind of act:

Focusing … is a process in which you make contact with a special kind of internal bodily awareness. I call this awareness a felt sense.

A felt sense is usually not just there, it must form. You have to know how to let it form by attending inside your body. (Gendlin, 1978/2007 p. 11)

If DES did not bracket Gendlin’s perspective, we would likely have been led to search for, to explore specifically Lena’s bodily expression in ways similar to Gendlin’s focusing. Instead, we tried to be even-handed about her sensing, happy to discover bodily aspects if they presented themselves. In so doing, we discovered that Lena’s sensing is not a bodily experience across any of her samples. If we had applied Gendlin’s focusing process with Lena, we might have discovered that lying behind her sensing was a felt sense that existed at a “deeper bodily level.” However, DES does not look for such behind-the-scenes processes.

As another example, DES would resist applying Gallagher’s (2003) phenomenologically based four experiential perspectives: the first-person-egocentric (“I do X here”), the first-person-allocentric (“X is done by me over there”), the third-person-egocentric (“I do X as if I were the other”), and the third-person-allocentric (“X is done by the other person”). If we had applied those perspectives to the injured-person experience (sample 11.4), we would have discovered a first-person-egocentric perspective (Lena’s directly apprehending her own thinking about damage caused by illness, as shown schematically on the left side of Fig. 2) and a third-person-egocentric perspective (Lena’s empathically entering into the experience of an injured person, as shown on the right side of Fig. 2). Gallagher’s other two perspectives do not apply to this experience. To the extent that we had been motivated by Gallagher’s perspective, we would have stopped there, and therefore we would have missed the sensing aspect of Lena’s experience (the recognition / incorporation of the third-person-egocentric perspective by / into the first-person-egocentric perspective aspect, as schematized by the lines influenced by the right side and then heading toward the left side of Fig. 2). That is, it was not merely that Lena imagined what it was like for a patient (“I do X as if I were the other”). That imagining took place, but beyond that, some recognition of that empathic imagining was incorporated into the first-person-egocentric perspective such that Lena experienced herself empathically entering the state of a damaged patient.

In short, DES avoids being driven by theoretical or rational categories. The DES aim is to describe, with as much fidelity as we can muster, Lena’s inner experience, not to fit Lena’s experience into predefined categories or to measure it along predefined characteristics. Thus, we prefer perhaps poetic descriptions such as “center of gravity” to disjunctive claims such as distinguishing between Gallagher’s first-person-egocentric and third-person-egocentric, because our use of “center of gravity” discourages subsequent fidelity-motivated investigators from snapping their new descriptions into one or another prior disjunctive categories. It would be much better for a subsequent investigator to try to describe her participant’s experience in high fidelity than to force a description into a Procrustean choice between prior but incomplete categories.

8) The DES procedure is tentative (part of the iterative procedure). It is entirely possible (although we took pains to avoid it) that Lena and we miscommunicated or entered into an unwittingly collusive misunderstanding of her experience—one could argue that the more interviews, the more occasions there are for interviewer influence. Perhaps other investigators would use DES with Lena but would not have discovered the multiple-centers-of-gravity phenomenon, either because we ourselves have been mistaken about that phenomenon or because they were not adequately observant. Perhaps yet other investigators would have discovered some other phenomenon even more interesting. Some might see that as demonstrating the “unreliability” of DES and cite that as reason to exclude DES from science. We see it as reflecting the world as it is: Any investigation into a relatively unknown arena must accept that some findings might be fairly easy to replicate (such as Lena’s low frequency of inner speaking), but others, which in the long run might be fundamentally important, may be challenging at the outset. Science will have to grapple with the implications of that.

9) The DES procedure is intensive. If we had discontinued sampling with Lena after four (or even eight) interviews, we would not have come to understand the multiple-centers-of-gravity characteristic of Lena’s experience.

10) DES resists theorizing about its results. Again part of the iterative procedure, DES seeks to describe phenomena with fidelity, on the faith that if the phenomena it describes are indeed important and robust, they will emerge again and again when (or if) others pursue phenomena with fidelity—especially if those pursuits are independent high-fidelity attempts as opposed to low fidelity Procrustean-categorization attempts (recall #7). Theorizing is appropriate after a sufficient critical mass of overlapping phenomena have been described.

We do not mean to suggest that the DES procedure is the best or only way to apprehend another’s pristine experience. We do think that the pre-registered nature of this study allows readers to explore in as much detail as desired the DES iterative procedure and its potential for gradual skill-building and iterative exploration. The study demonstrates (1) that (at least sometimes) people’s confident self-characterizations of their own experience are substantially mistaken; (2) that (at least sometimes) people’s mistaken self-characterizations can be easily altered by careful discussions of a few randomly selected experiences; and (3) some experiential phenomena emerge only after substantial struggle, requiring substantial care and probably including something similar to (or better than) DES’s iterative procedure.

Availability of data and material

All data (videos and transcripts of DES interviews) from this study are freely available online at http://hurlburt.faculty.unlv.edu/lena/do_I_have_internal_monologue_sampling.html.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Note that the experience, though grasped as ongoing at a particular “microsecond” in time, is not itself constrained to be of short duration (see Hurlburt, 2011c, Sect. 5, “Diachronic”). Further note that “microsecond before” is intended as a metaphorical description, not a time measurement.

The term “internal monologue” is not precise (DES does not use that term, preferring “inner speaking” or “inner hearing” (Hurlburt et al., 2013)). However, “internal monologue” is the term used by Ryan and then by Lena, so the question is whether Lena’s inner experience included ubiquitous internal monologue however Lena defined that term. We will conclude that the answer is No.

DES typically distinguishes inner speaking that is freely engaged in and inner speaking that is tied to an ongoing verbal task such as reading, writing, typing, or texting.

Lena also reported visual imagery in the two samples from day 1, but they are not counted here.

We note that micro-phenomenology considers its method to be iterative, for example, “micro-phenomenological interviews have an iterative structure which helps subjects repeatedly evoke the experience to be described while guiding their attention towards a progressively finer synchronic and diachronic mesh” (Petitmengin et al., 2018 p. 5). However, with some exceptions (e.g., Petitmengin et al., 2017), the micro-phenomenological iteration is usually a within experience undertaking, repeatedly returning to the same experience, aiming for a deepening and refining of an already-encountered aspect.

References

Gallagher, S. (2003). Complexities in the first-person perspective: Comments on Zahavi’s self-awareness and alterity. Research in Phenomenology, 32, 238–248.

Gendlin, E. T. (1978). Focusing ([1st ed.].). Everest House.

Giorgi, A. (1975). An application of phenomenological method in psychology. Duquesne Studies in Phenomenological Psychology, 2, 82–103.

Hardwicke, T. E., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2018). Mapping the universe of registered reports. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(11), 793–796. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0444-y

Heavey, C. L., Hurlburt, R. T., & Lefforge, N. L. (2010). Descriptive experience sampling: A method for exploring momentary inner experience. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(4), 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880903009274

Hurlburt, R. T. (1990). Sampling normal and schizophrenic inner experience. Plenum Press.

Hurlburt, R. T. (1993). Sampling inner experience in disturbed affect. Plenum Press.

Hurlburt, R. T. (2009). Iteratively apprehending pristine experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 16(10-12), 156-188.

Hurlburt, R. T. (2011a). Investigating pristine inner experience: Moments of truth. Cambridge University Press.

Hurlburt, R. T. (2011b). Descriptive Experience Sampling, the Explicitation Interview, and pristine experience: In response to Froese, Gould, & Seth. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18(2), 65–78.

Hurlburt, R. T. (2011c). Nine clarifications of Descriptive Experience Sampling. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18(1), 274–287.

Hurlburt, R. T. (2020). DES-IMP: Descriptive Experience Sampling interactive multimedia project. http://hurlburt.faculty.unlv.edu/desimp/labs/lab0/lab0.html

Hurlburt, R. T., & Akhter, S. A. (2006). The descriptive experience sampling method. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 5, 271–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-006-9024-0

Hurlburt, R. T., & Heavey, C. L. (2006). Exploring inner experience: The descriptive experience sampling method. John Benjamins.

Hurlburt, R. T., & Heavey, C. L. (2015). Investigating pristine inner experience: Implications for experience sampling and questionnaires. Consciousness and Cognition, 31, 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2014.11.002

Hurlburt, R. T., & Krumm, A. E. (2020). Do I really have internal monologue? (Reality TV about inner experience). http://hurlburt.faculty.unlv.edu/lena/do_I_have_internal_monologue_sampling.html

Hurlburt, R. T., & Schwitzgebel, E. (2007). Describing inner experience? Proponent meets skeptic. MIT Press.

Hurlburt, R. T., & Schwitzgebel, E. (2011). Presuppositions and background assumptions. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18(1), 206–233.

Hurlburt, R. T., Heavey, C. L., & Bensaheb, A. (2009). Sensory awareness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 16(10–12), 231–251.

Hurlburt, R. T., Heavey, C. L., & Kelsey, J. M. (2013). Toward a phenomenology of inner speaking. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(4), 1477–1494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.10.003

Hurlburt, R. T., Alderson-Day, B., Fernyhough, C. P., & Kühn, S. (2015). What goes on in the resting state? A qualitative glimpse into resting-state experience in the scanner. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, article 1535, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01535

James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology (Vol. I). Holt.

Langdon, R. (2020). Today I learned that not everyone has an internal monologue and it has ruined my day [blog post]. Inside My Mind. https://insidemymind.me/2020/01/28/today-i-learned-that-not-everyone-has-an-internal-monologue-and-it-has-ruined-my-day/

Petitmengin, C. (2011). Describing the experience of describing? Comments on Hurlburt and Schwitzgebel’s “Describing inner Experience?” Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18(1), 44–62.

Petitmengin, C., Baulac, M., & Navarro, C. (2006). Seizure anticipation: Are neurophenomenological approaches able to detect preictal symptoms? Epilepsy & Behavior, 9, 298–306.

Petitmengin, C., Van Beek, M., Bitbol, M., Nissou, J. M., & Roepstorff, A. (2017). What is it like to meditate? Methods and issues for a micro-phenomenological description of meditative experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 24(5–6), 170–198.

Petitmengin C., Remillieux A., & Valenzuela-Moguillansky C. (2018). Discovering the structures of lived experience. Towards a micro-phenomenological analysis method. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 18(4), 691–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-018-9597-4

van Manen, M. (2016). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere thanks and respect to Lena for her participation in this project. We hope that science will profit from the bravery and openness she displayed in sharing her innermost experiences with the world.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accord with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects.

Consent to participate

All parties provided verbal consent to participate and consent was discussed and renewed at each juncture in the project. Consent is documented in multiple places in the available online materials.

Consent for publication

All parties provided in writing consent for publication.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krumm, A.E., Hurlburt, R.T. A complete, unabridged, “pre-registered” descriptive experience sampling investigation: The case of Lena. Phenom Cogn Sci 22, 267–287 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-021-09763-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-021-09763-w