Abstract

This article examines a national policy of performance-related pay for teachers in the educational context of England, as understood in relation to the concept of New Public Management. Using a mixed methods approach employing surveys and in-depth interviews, the article considers the perspectives of working teachers, thus engaging directly with those who might be incentivized (or disincentivized) by performance pay. Significant implications for the broader international policy context are drawn in terms of teachers’ complex and problematic attitudes towards incentivization, particularly when performance pay is located within a wider agenda of New Public Management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Performance pay for teachers is a topic of sustained international interest and relevance (Conley & Odden, 1995; Dalton & Marcenaro-Gutierrez, 2011; DeSander, 2000; Eren, 2019; Firestone, 1991; Hill & Jones, 2021; Malen, 1999; Mintrop et al., 2018; OECD, 2012; Pham et al., 2021; Springer et al., 2012; Woessmann, 2011) and can be located within a broader global policy agenda of critical contemporary importance, namely, New Public Management (Helgetun & Dumay, 2021; Hood, 2000; Hood & Peters, 2004; Greany, 2020; Kulz, 2021; Pagès, 2021; Tolofari, 2005; Verger & Curran, 2014; Wilkins et al., 2019, 2021). Various studies have sought to examine possible links between teacher performance pay and grade outcomes, including some indicating positive correlations (e.g., Woessmann, 2011), or mixed findings, such as efficacy contingent on specific merit pay program (e.g., Pham et al., 2021; Kelley, 1999), or outcomes varying by school subject (e.g., Eren, 2019), or being effective only under very specific economic conditions (e.g., OECD, 2012), or where the effect of the incentive is negatively skewed (e.g., Hill and Jones, 2021) or else where no correlation is found (e.g., Springer et al., 2012).

However, the perspectives of those teachers who are incentivized (or disincentivized) by such policy initiatives can be more fully considered (Mintrop et al., 2018; Lee & Nie, 2017; Lundstrom, 2012; Mahony et al., 2004) and the need for such empirical work has been clearly identified in regard to performance pay (Pham et al., 2021; Eren, 2019; Woessmann, 2011). Indeed, as Firestone (1991, p.270) notes, it is only once teachers’ perspectives are garnered that “problems appear” with performance pay and “links between teacher reforms and changes in teaching and teacher motivation become apparent,” with Heneman (1998) also stating the importance of understanding teachers’ motivational reactions to performance pay. This is particularly the case given the prominence and potential influence of recent work on performance pay which relies either wholly (Eren, 2019; Woessmann, 2011) or to significant degree (Pham et al., 2021) on sources of data other than teacher perspectives. Thus, there is a present need for work which offers a counterbalance, by foregrounding the views of working professionals. Indeed, much of this same work (e.g., Eren, 2019; Woessmann, 2011) has also called for such greater nuance because of the challenges associated with disentangling the various effects associated with performance pay. One key source of this greater nuance is the perspectives of those being incentivized, hence the need for work in this vein. Further, the context explored (England—to be discussed in detail below) represents a key area of contemporary inquiry because of the scale and international relevance of recent policy on performance pay. This study therefore examines the views of working teachers in a context where a major recent policy change has occurred in respect to performance-related pay, drawing fresh conclusions significant from a broader international perspective. Participants’ perspectives on performance pay in the present study prove at best ambivalent, with considerable reservations expressed as to the aims, implementation, and unintended consequences of such a policy, especially when examined through the lens of New Public Management.

1 New Public Management and performance pay

Before considering the specific policy, it is important to observe that performance pay can be located within a wider geo-political trend, New Public Management (NPM). The conceptualization of NPM emerges significantly from the work of Hood, both in isolation (1976; 1991; 2000) and in collaboration (Dunleavy and Hood, 1994; Hood & Peters, 2004). Hood (1991, p. 4–5) defines the “doctrinal components” of NPM as including:

explicit standards and measures of performance…greater emphasis on output controls (resource allocation and rewards linked to measured performance)…[a] shift to greater competition…[and] stress on private- sector styles of management practice… parsimony in resource use.

Internationally, it is characterized by “widespread use of data, infrastructures, comparative-competitive frameworks, test-based accountabilities” (Wilkins et al., 2019, p.147). Performance pay thus forms one very important and totemic element of this wider agenda, as the accountable, competitive, and intensively managed subject strives for reward (or the avoidance of punishment). Yet whilst this policy agenda can be discerned globally (Apple, 2011; Tolofari, 2005; van der Sluis et al., 2017; Verger & Curran, 2014), nonetheless, as Wilkins et al. (2019, p.158) argue, it is essential to be mindful of “the complex patterning and layering of NPM within different geo-political settings owing to the historical development of their unique political-administrative structures.” In other words, NPM shapes itself to a specific context and it is therefore important to explore the policy environment particular to England and the crucial empirical data this offers up in respect to performance pay. This context is particularly relevant not least given Hall and Gunter’s (2016, p.22) apposite description of England as the NPM “laboratory” of European education, and performance pay can be seen as one of its most significant experiments. Likewise, given the nakedly market-inspired characteristics of performance pay and England’s particularly charged emphasis on the competitive-comparative individual teacher, it can be seen as an emblematic expression of the broader NPM policy environment.

1.1 The English performance pay policy context

In England, it is possible to delineate the intensification of a policy trend of educational accountability over the last 30 years. Early legislation sets a tone or pathway for later reforms (2000 onwards) which were specifically related to performance pay. For example, the 1988 Education Reform Act is a key starting point, ushering in the control of the curriculum by government, with teachers instructed to teach specific content. In 1992, with the Education (Schools) Act, another key moment occurs: the creation of a new inspectorate, the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) and the more punitive approach to school inspection this entailed. Increasing teacher accountability proceeded unabated with (the politically centrist) New Labour’s introduction of the Excellence in Schools White Paper in 1997 (critical to the introduction of target-setting culture) and the School Standards and Framework Act (including yet more punitive powers for Ofsted) in 1998. Importantly, this succession of reforms was bi-partisan; Bartlett (2000, p.36) has described how “teacher appraisal, as part of Conservative attempts to exert increasing control” was then furthered by “Labour, using the rhetoric of partnership and consensus…increasingly towards the original Conservative goal.” Bartlett (2000, p.36) also highlighted that Government would “shortly be able to provide a means of exerting greater control…by assessing performance and linking it to pay”; subsequently, in 2000, this government introduced the Performance Management Framework, creating a “Threshold” for future pay progression. This “Threshold” system entailed time-served pay progression for the first 6 years of service following qualification, leading to a performance threshold only to be crossed by satisfactory appraisal against performance benchmarks which were set for an upper pay scale consisting of three bands. In a government-sponsored enquiry, Atkinson et al. (2009) asserted a positive causal link between the “Threshold” pay system and performance: “value added increased on average by about 40% of a grade per pupil” (2009, p.251). However, whilst headteachers were consulted in a qualitative way in this study, there was no examination of the perceptions of those being incentivized (i.e., teachers). By contrast, Mahony et al. (2004) offer a very different view of the effectiveness of “Threshold” performance pay in England, identifying “little evidence…even though teachers were successful [in securing pay progression], that Threshold has done anything to redress the deep alienation in the work of many teachers” (p.453). The study predicted “what is educationally important will either become regarded as marginal or felt to be in conflict…students could become further reduced to the means through which teachers meet their targets” (Mahony et al., 2004, p.453). Such a view of “Threshold” was echoed by Cutler and Waine (2000), who noted the counterproductive nature of numeric performance targets serving to undermine teachers’ meaningful professional development. Similarly, they describe “Threshold” as a means of divisive individuation which inhibits teamwork and collegiality, alongside other concerns including associated workload and fairness/consistency of appraisal. Indeed, such outcomes (and others, such as problems associated with implementation due to the complexity of schools as organizations) were anticipated by Storey (2000), even prior to the policy’s actual inception. Arguably, such views are even more applicable to the new and intensified system introduced in 2013 (discussed below). These references to factors such as divisive individuation, target culture, and intensive appraisal can again be located squarely within a NPM agenda (for example, Helgetun and Dumay, 2021; Kulz, 2021; Pagès, 2021; Wilkins et al., 2021), whereby “homo-economicus…[becomes a]…competitive creature” (Read, 2009, p.28).

In 2006, further reforms were enacted, triggering more intensive documentation of performance-related activities and the widespread formal grading of lessons, through the requirement that “the performance of every teacher at the school shall be managed and reviewed on an annual basis” (DFES, 2006, 12.1) with the requirement to “state…results…and how these will be measured” (7.9.a) and “include a classroom observation protocol” (7.9.e). Such policies have led Gunter (2008, p.225) to observe that “controlling…conditions of work…are core preoccupations of both New Right and New Labour governments,” with Beck (2008, p.133) noting that such successive reforms are “a systematic effort…to marginalize competing models of professional organization.” Thus, over this period of policy change, there was the “effect of turning the status of teachers from autonomous professionals into directed technicians” (Leaton-Gray, 2006, p.307). Such policies can be clearly related to the international agenda of NPM, as Whitty notes (2008, p.170): this “major policy thrust…is by no means restricted to England. Choice and competition, devolution and performativity, and centralization and prescription now represent global trends.”

In 2010, this agenda of teacher accountability intensifies with “The Importance of Teaching” White Paper, “making schools more accountable to their communities, harnessing detailed performance data” (DfE, 2010, p.7). The sense of continuation has been observed by Bates (2012, p.89) to “reveal the same neoliberal thinking as their New Labour predecessors” and by Lumby and Muijs (2014, p.535) “as continuing the late twentieth century neoliberal capitalist project…furthering an agenda of control” and thus again expressive of NPM. Morris (2012, p.104) also notes how this White Paper shapes evidence, “based on invalid inferences from the data…which [in fact] indicates that…[no improvement in] pupil performance” to fit a pre-ordained agenda of NPM. Subsequently, the Education (School Teachers’ Appraisal) (England) Regulations (DfE, 2012), whilst less prescriptive in the sense of volume of regulation, represented another intensification of the environment of accountability, clearing the ground for the 2013 policy which replaced the Threshold model.

In the current English context, the key changes introduced have been the removal of pay progression based on years’ service, and the linkage of all pay progression to performance, with individual teachers’ pay increasing at different rates. Interestingly, the DfE’s (2019) most recent guidance on remunerating teacher performance is at pains to articulate the need for a “clear” process, referenced on no fewer than 33 occasions (and perhaps expressive of its inherent ambiguities). However, the document outlines how the policy might work in practice, recommending specific increments linked to precisely pre-determined criteria: “Teachers will be eligible for a pay increase of £x…if…£y…if…£z if…” (DfE., p.55), with such “judgements of performance” and their associated increment made on the “extent to which teachers have met their individual objectives and the relevant standards” informed by a composite of measures including “impact on pupil progress; impact on wider outcomes for pupils; improvements in specific elements of practice, such as behavior management or lesson planning; impact on effectiveness of teachers or other staff; wider contribution to the work of the school)” (DfE. p.56) with the relative weighting and evidencing of such measures determined by the particular school. Thus, again, the policy can be seen as emblematic of the NPM agenda, given the emphasis on comparison, measurement, competition, and accountability (see, for example, Tolofari, 2005; Verger and Curran, 2014; Wilkins et al., 2019).

In terms of distinguishing this policy from others elsewhere, it should be noted that it provides punitive grounds whereby “Teachers judged as being in the bottom 5/10/x% of teachers in the school will not be eligible for any increase” (DfE. p.57). Importantly, this would differentiate such a policy from that delineated by Salazar-Morales (2018), whereby performance pay is understood as an incentive only; instead, in the English context, pay might also be punitive. Likewise, this policy relates specifically to the compulsory introduction of performance pay for all currently in-service teachers. It can thus be differentiated from studies which examine signing bonuses for entrants to the profession (for example, Liu et al., 2004) and from studies examining an option to join an incentive scheme (Goldhaber et al., 2016). However, this said, there may be shared commonalties with these studies around the limited attractiveness of financial inducements or incentives for teachers. Similarly, the policy relates to the remuneration of individual teachers and therefore is distinct from studies which examine team performance pay initiatives (Springer et al., 2012), but might again share commonalities with this study in terms of teachers not having sufficient clarity on how a bonus program operates (whether because of communication or inherent design) and this could be as applicable to individual incentivization as much as to team incentivization.

As schools are “free to adopt their own approaches” (DfE. p.5), practical enactment on the ground is inhibited by a policy which itself equivocates over implementation. This relates to Wilkins et al. (2021, p.28) who argue a characteristic of NPM is “the separation of strategic policy-making and policy implementation,” thus problematizing enactment. Yet some seemingly more nuanced attitudes are also evident: “Schools should…enable teachers to demonstrate performance, as well as results.” (DfE, 2019, p.13), though problematic if teachers perceive themselves judged by numeric targets, rather than more holistically (Parcerisa, 2020; Peace-Hughes, 2020; Piattoeva, 2021; Smith & Holloway, 2020). Similarly, the notion that “collection of evidence should be proportionate and not increase workload for teachers” (DfE, 2019, p.18) seems reasonable, though whether this accords with teachers’ perceptions of bureaucracy is debatable (Humes, 2021; Whiteoak, 2020).

1.2 International perspectives on teacher performance pay

OECD (2012) claims “the overall picture reveals no relationship between average student performance…and performance related pay” (2012, p.2) across countries, which suggests a worrying finding for the current pay policy in England. However, they argue where teacher salary is lower than 15% below GDP per capita, then financial incentives have greater impact, concluding that “countries which do not have the resources to pay all well” (OECD, 2012, p.2) should consider performance pay. Yet Dalton and Marcenaro-Gutierrez (2011) draw on data from 39 different countries to argue a causal link between teacher quality and higher basic remuneration in relation to GDP only (i.e., not enhanced through bonus payments), arguing teachers need simply to be paid well to start off with. By contrast, Woessmann (2011) asserts “countries that adjust salaries…perform about 25% of a standard deviation higher” in mathematics with “similar associations for reading and…smaller, but…significant associations for science” (p.405), acknowledging however that around “70%” of the data was based on mathematics testing, with “less detailed testing of science and reading” (2011, p.408). Whilst OECD (2012) and Woessmann (2011) offer differing conclusions, there is also an important similarity to note in terms of a complexity associated with international comparison; neither OECD (2012) nor Woessmann (2011) fully disaggregates different countries’ approaches. For example, in some countries, performance pay means permanent salary gains, whereas for others, it is an annual bonus system.

Eren (2019) observed a similar association to that of Woessmann (2011) in relation to mathematics outcomes in Louisiana, though “no effects” (p.869) in language and science outcomes. Similar positive (if modest) associations have been noted by Liang and Akiba (2015) in the middle school context in Missouri. Yet contrastingly, Fryer’s (2011, p.400) study in the New York City area concludes “teacher incentive scheme piloted in 200 NYC public schools did not increase achievement.” However, Pham et al.’s meta-analysis (2021, p.29) offers a more mixed perspective: “a positive…effect of teacher merit pay on student test scores,” but “differing effects imply that not all merit pay programs are motivating,” a view shared by Kelley (1999). Relatedly, however, Eren (2019, p.888) concludes it is difficult to “disentangle the effect of performance-based compensation from other elements” influencing teacher-student performance and “cannot conclusively infer whether achievement gains …reflect true learning or not.” A more general point is also germane, namely that associations made by such studies do not imply causality, though a danger exists that such inferences might be drawn. In reality, various unmeasured variables may be at play.

This quantitative picture linking student outcomes and performance pay also warrants examination in relation to other available data sources internationally. For example, taking a country which OECD claims operates a relatively successful performance pay system (Sweden) and comparing this against other evidence sources (Lundstrom, 2012), it appears test scores alone are limited indicators. Lundstrom’s (2012) qualitative study argues that performance pay not only fails to produce positive outcomes, but is actively counterproductive, disincentivizing teachers due to factors such as an absence of transparency and problematic measurement of performance. Here, Hood and Peters’ (2004) description of the Mertonian law of unintended consequences comes to mind, with NPM inadvertently achieving the opposite of its stated goal (diminished rather than improved performance).

Likewise, where positive (if not uniform) correlations have been found in the United States (for example, Eren, 2019), this can be juxtaposed with studies from the same context which are generative of data presenting teachers’ complex and problematic attitudes towards performance pay (Conley and Oddin, 1995; Firestone, 1991; Mintrop et al., 2018; Smylie & Smart, 1990; Springer et al., 2012). Findings similar to Lundstrom’s (2012) work include concerns over clarity (Springer et al., 2012) or subjective judgement of performance (Conley and Oddin, 1995) or fairness of implementation (DeSander, 2000; Heneman & Milanowski, 1999; Malen, 1999) and are ably summarized overall by Firestone (1991, p.285): “there are significant barriers to the reward values of merit pay…teachers question…fairness…accuracy of assessment…equity of distribution and barriers to collegiality.” Yet at the same time, the effectiveness of a performance pay policy might not solely be a question of its practical operationalization (simply solving the question of performance measurement), because as Smylie and Smart (1990, p.151) found, “singular attention to technical precision…is inadequate to garner substantial levels of teacher support,” arguing that “instead…unless…implications for teacher professional relationships, learning, recognition, and empowerment are addressed adequately, the prospects of…success, are seriously diminished.” This emphasis on the importance of teachers’ support for merit pay has also been underlined by DeSander (2000). Likewise, as Pham et al. (2021, p.30) note: “studies of teacher perceptions report that teachers have difficulty trusting interventions based solely on student test scores,” a view echoed by Piattoeva (2021) and Smith and Holloway (2020). Here, definitions of “performance” are important, particularly in relation to a teacher’s working context. For example, effective “performance” in an economically deprived context may look very different to “performance” in a more affluent school, with teachers pursuing a range of goals which extend beyond graded outcomes (e.g., Lupton, 2014; Lupton and Thrupp, 2013). There is also the question of the extent to which teachers can or should be held solely or largely responsible for performance outcomes given the complex societal factors which relate to structural poverty (McKinney, 2014). Relatedly, there is also a more general question of the distinction between constitutive and instrumental performance (Proudfoot & Boyd, 2023), whereby a professional may feel the need to choose between, on the one hand, the holistic educational best interests of learners (constitutive performance) and, on the other, the raw pursuit of grades because of the rewards and punishments at play for teachers (instrumentalism).

Given such complexities, perhaps unsurprisingly, Woessmann (2011) and Eren (2019) conclude greater analysis is needed, both in terms of contextual variance and in regard to richer data extending beyond the purely quantitative association of performance pay and student outcomes.

These various international studies should also be related to the broader notion of NPM. Tolofari (2005) describes “NPM…[as] characterized by marketisation, privatization, managerialism, performance measurement and accountability” (p.75), various features which are referenced extensively by the studies above. Wilkins et al.’s (2019) idea of a mutable New Public Management which shapes itself to different policy environments is also relevant. In the international contexts above, there are differences such as governance structures and specific pay systems, but these are adaptive variations on recurring themes within NPM.

2 Method: generating teachers’ views on performance pay

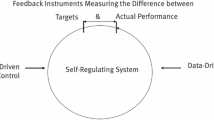

This study employed a convergent mixed methods approach to data generation and analysis (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018), illustrated by Fig. 1. Using Creswell and Plano Clark’s (2018) approach to notation, this study specifically made use of a “QUAN + QUAL” convergent design, where “both strands had equal emphasis, and the results of the separate strands were converged” (Creswell and Plano Clark, p.63). However, as Bazeley (2012) and Law (2004) astutely observe, such a process of convergence can be complex and iterative in practice, hence the circular arrow in the figure below to capture this aspect. This complexity noted, each of these strands will be examined separately in the interests of clarity, before moving to the synthesis phase as indicated by Fig. 1. Paradigmatically, this mixed methods study is located within the critical realist tradition; space and focus do not allow for an extended discussion, but a related methodological paper explores this at length (see Proudfoot, 2023).

2.1 Quantitative survey design

The quantitative element of this research consists of an 18-item Likert scale survey measuring teachers’ motivational dispositions towards performance management, using self-determination theory (SDT) as the organizing framework (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020). This was chosen as performance pay can be clearly understood as a “a motivational approach” (Ryan & Weinstein, 2009, p.225), because of the central emphasis on the reward and punishment of specified behaviors and outcomes, a view supported by Carr (2015) and Heneman (1998). The survey was first developed through evaluation of previous SDT surveys, with item statements making use of established key words and phrasing and a seven-choice response range (Tremblay et al., 2009; Gorozidis & Papaioannou, 2014; Fernet et al., 2008). Each construct within self-determination theory was measured by 3 items. The construct is given below:

The figure above illustrates the various elements of the self-determination theory continuum (Fig. 2), but the present article’s findings concern most specifically amotivation and external regulation and thus these warrant further explication. External regulation is in a sense more straightforward to define, relating as it does to a controlling form of extrinsic motivation pertaining principally to the salience of reward and punishment (or the promise/threat of these). Thus, it is a construct of considerable relevance to a study of performance pay, with the reward element being self-evident, but the notion of punishment also being applicable (for example, through withholding pay progression). The second area of importance to the present study is amotivation as this was most salient in the findings. Amotivation has been acknowledged as a complex construct within the self-determination theory framework (Cheon & Reeve, 2015; Legault et al., 2006; Markland & Tobin, 2004; Shen et al., 2010), with Shen et al. (2013, p.209) describing its “multidimensional” character, including “deficient ability beliefs, deficient effort beliefs, insufficient…values, and unappealing characteristics of…tasks.” Markland and Tobin (2004, p.195) have also noted that amotivation can variously “arise from a lack of perceived contingency between behavior and desirable outcomes, a failure to value the behavior, or a feeling that one is not competent to successfully engage in it.” Thus, the survey items sought to encompass aspects of this complexity, which fall under the broad heading of amotivation, defined more generally as the absence of a sense of purpose or impetus (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020). Example statements for these constructs are given for external regulation: “I am motivated to be a better teacher by my school’s system of financial reward” and “My motivation to be a better teacher is increased by the prospect of greater pay rewards” and for amotivation “Performance management systems have taken away my previous motivation to be a better teacher” and “Performance management processes do not have any relevance to my motivation to be a better teacher.” These examples are chosen as they relate most closely to the subsequent analysis. The survey was then piloted, indicating a plausible instrument with ordinal alpha = 0.803745.

For the full distribution, this survey was released via a university alumni database (with institutional clearance) in order to approach teachers through a means which did not involve circulation via school hierarchies (because of the managerial aspect). Participants were asked to identify a range of characteristics to enable comparison by groups. These were school type, number of years’ service, roles and responsibilities, and gender. Crucially for the present paper, participants were also asked to identify whether they worked in a school in which performance pay was in operation. The available response categories for this were Yes, No, and Don’t Know; these were employed as, whilst by government regulation all schools in England must implement performance pay, there was the possibility of variation in terms of schools’ responsiveness to this requirement and also how schools have elected to communicate this policy to teachers themselves.

Descriptive statistics were analyzed and the Kruskal-Wallis tests, appropriate for ordinal data such as Likert scales (Kuzon et al., 1996; Shearman & Petocz, 2013), were used to identify any meaningful variations between groups. Post hoc Dunn-Bonferroni tests were then employed to identify specific statistically significant pairwise combinations, where the Kruskal-Wallis tests identified the possibility of differences.

2.2 Qualitative approach to data generation

Qualitative data were generated by two means: semi-structured interviews and survey open responses. These methods were considered appropriate for addressing the research aim of garnering perspectives on performance pay as they enabled the generation of teacher voice. Further to this end, in the case of both means of data generation, approaches were made so as to not entail the use of school management structures. In the case of the survey open response, this was distributed via an Initial Teacher Education alumni database as already outlined in respect to the quantitative element. Similarly, participants for semi-structured interviews were approached via the present researcher’s informal networks. In both cases, the rationale for such approaches was the same: given descriptions of school leaders’ silencing and marginalization of teachers’ views on performance management (Courtney & Gunter, 2015) and the risk of “teachers’ sensitivity and uneasiness in participating willingly” (Lee & Nie, 2017, p.276) given the nature of the topic, it was thought prudent to pursue direct engagement with working teachers.

2.3 Survey open response design

The open prompt “Please use the box below to add any other thoughts that you wish” was used. This was appended to the 18-item Likert scale survey already outlined. The intent with this open prompt was to create neutral phrasing which enabled participant teachers to make any further comment on any aspect of performance management. Performance pay was a highly salient area for participants, as will be discussed.

2.4 Interview design

Interviews were semi-structured in nature (Gill et al., 2008), employing a funnel design (Brenner, 2006) from the broad theme of general motivations to improve or develop as teacher, through to specific attitudes on the effectiveness of performance management and lastly to performance pay itself (if this had not already arisen). Again, motivation was chosen as an organizing structure due to the centrality of incentivization to the notion of performance pay (Carr, 2015; Heneman, 1998; Ryan & Weinstein, 2009). The funnel structure of the interviews was as presented as “What makes you want to develop further as a teacher?,” followed by “To what extent are your motivations to develop shaped by the school you work in?,” and finally, “Does performance management motivate you to be a better teacher?” Importantly, however, such an approach was sufficiently flexible to allow for the “contents to be reordered, digressions and expansions made, new avenues to be included” (Cohen at al. 2007, p.182). This open approach demonstrated particular utility, as teachers proved keen to discuss aspects performance pay.

2.5 Participant selection and characteristics

As noted, participants were surveyed or interviewed in respect to their general motivations and, for the present article, open responses (N = 68) and interviews (N = 7) were considered relevant where they pertained to performance pay. For example: (a) the most recent iteration of performance pay policy was now in active operation in their school or (b) experience of previous “Threshold” pay measures meant comments were made that were also relevant to the current policy or (c) whose comments on financial motivations in general or on given hypothetical pay scenarios are readily applicable to performance pay as articulated by the current policy or (d) that a participant teacher (for example, “Grace”) had worked in contexts where performance pay was in explicit operation and made reference to this (but whose school context at time of interview was not one where performance pay was overtly in use) or (e) where the effects of performance pay were felt though the policy was not explicitly articulated by management (such as “Ian”).

Participants quoted are given as Pseudonym, Years’ Service, PRP?, and Age Phase. Here, PRP? denotes whether a teacher was explicitly aware of performance-related pay in their current school when asked this question. However, responses were at times ambiguous in this respect and this is explored in the analysis.

2.5.1 Quoted survey open response participants

Gillian (3yrs, PRP? Yes, Elementary).

Margaret (9yrs, PRP? Yes, Elementary).

Tommy (3yrs, PRP No, Elementary).

Kath (10yrs, PRP? Yes, Secondary).

Melanie (3yrs, PRP? Yes, Secondary).

Joanna (9yrs, PRP? Yes, Secondary).

Mandy (5yrs, PRP? Yes, Elementary).

Amaya (6yrs, PRP? Don’t Know, Elementary).

Jimmy (1 year, PRP? Don’t Know, Special School).

2.5.2 Quoted interview participants

Ian (3yrs, PRP? Yes, Secondary).

Pete (10yrs, PRP? No, Elementary).

Lee (12yrs, PRP? No, Elementary).

Grace (9yrs, PRP? Don’t Know, Secondary).

Natalie (4yrs, PRP? Don’t Know, Secondary).

Katie (6yrs, PRP? Don’t Know, Elementary).

Heather (2yrs, PRP? Don’t Know, Elementary).

2.6 Generalization and transferability

In respect to qualitative data, it is important to comment in respect to generalization/transferability. As Firestone (1993, p.16) notes, possibilities include “(a) extrapolation from sample to population, (b) analytic generalization or extrapolation using a theory, and (c) case-to-case translation” with the latter two cases applicable to qualitative work. The present paper, following Firestone (1993), seeks to make analytic generalizations (that is, the relation of data to general analytical themes) and generate possible case-to-case translations (that is, the transferability of specific findings to other persons or contexts), deferring to the reader on this: “it is the readers and users of research who “transfer” the results” (Polit & Beck, 2010, p.1453). The present paper does not seek to extrapolate from sample to population; participant numbers are such that findings are presented tentatively as valuable insights in themselves which may also be suggestive of broader teacher perspectives, rather than a claim being made they are fully representative of the profession as whole.

2.7 Approach to theme generation

For a systematic approach to theme generation, Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six stage approach to inductive thematic analysis was employed (familiarization with data, generation of initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes, final analysis). This was used in conjunction with Nowell et al.’s (2017) trustworthiness criteria, including dependability, where the approach to data collection is carefully documented, hence the detail and transparency above in relation to methods. Nowell et al. (2017) similarly emphasize the importance of credibility, recommending a process of peer debriefing/external checking to ensure the robust critique and justification of themes generated, achieved in this case through review of themes with academic colleagues. Triangulation of open responses and interview data took place (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018), meaning a parallel analysis, followed by cross-checking and combination (though inevitably “messy” (Law, 2004) and involving iterations of analysis).

3 Quantitative analysis

3.1 Initial descriptive statistics

Three hundred twenty-three teachers replied to the survey at a respondent rate of 9.8% (a rate anticipated when employing a university alumni database—see Lambert and Miller, 2014). Cook et al. (2000) emphasize the value of a broad respondent range and this was positively the case: newly qualified teachers, 68; less than 6 years’ service, 113; more than 6 years’ service, 53; middle leadership responsibility holder, 38; department manager, 18; senior school leader, 15; other, 18. Data screening led to the removal of four cases for intentional mis-responding or entry error (resulting in N = 319). For the performance pay Kruskal-Wallis tests, any individuals not presently working in schools in England were removed (supply teachers or the unemployed, for example), as they were not presently subject to performance pay. Likewise, those who self-identified as senior leaders were considered not subject to performance pay as applied to classroom teachers and so were also removed from this analysis (N = 275). Initial indicators for the viability of the instrument proved very encouraging, with ordinal alpha = 0.792125 (Table 1).

As already noted, participants responded across seven categories. These were as follows: (1) Strongly Disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Disagree Somewhat, (4) Neither Agree/Disagree, (5) Agree Somewhat, (6) Agree, (7) Strongly Agree. A first point to observe is that there is evidently higher perceived motivation to be discerned in terms of the medians for those variables measuring for the identification, integration, and intrinsic aspects of the SDT continuum, which in itself suggest that there may be other factors driving teacher motivation which are more potent than performance pay. Additionally, insofar as these impetuses might be in conflict or contradiction with performance pay, this represents a potential complication for such a policy and this will be discussed further in relation to the qualitative findings at the point of synthesis. Conversely, there was lower perceived motivation for variables measuring for external regulation and introjection, with aspects of external regulation in particular areas representing where teachers disagreed. This included a variable asking if their present pay structure was an impetus “I am motivated to be a better teacher by my school’s system of financial reward,” suggesting that contemporary practical implementation of performance pay is problematic and that the policy as configured is poorly effective (if not inoperable). Likewise, a variable measuring for external regulation which explicitly foregrounded punitive practices “Intensive managerial scrutiny motivates me to be a better teacher” was disagreed with by respondents. Each of these aspects will be discussed more fully in relation to qualitative findings at the point of synthesis in terms of both the present workability of approaches to incentivization and the demotivating use of punitive practices. This said, some variables are worth slightly longer pause. There was a slightly higher perceived motivation towards a variable measuring for external regulation which specifically referenced the prospect of greater pay reward (V3). Crucially, this variable measured for the future prospect of reward, rather than the present fact of it; this will be given fuller consideration in relation to other qualitative findings in due course, linked to the idea that if a pragmatic and fair approach could be found (if feasible), then this might possess some traction (albeit mild) for some teachers (alongside other more potent perceived impetuses). Similarly, there was some higher perceived motivation towards some introjection variables, again suggesting that notions of ego and esteem may carry motivational potency (however this is discussed more fully in a separate paper; Proudfoot, 2022). Considerable ambiguity also emerged in respect to the amotivation aspect, which will be discussed in relation to the Kruskal-Wallis findings below in terms of the complexity of this aspect of the SDT construct.

3.2 Kruskal-Wallis tests and post hoc Dunn/Bonferroni tests

In terms of variation by performance pay awareness, there were two findings of significance. The first was an absence in variation between groups on the basis of awareness of performance pay in relation to external regulation (reward and punishment). It might be considered, for example, by architects of incentive pay policies, that in schools where performance pay was explicitly in use, this would result in external regulation being a more salient and potent motivator. However, such a correlation appeared not be evident in the present study, with the Kruskal-Wallis test showing no such variation.

Instead, a second difference emerged with a variable measuring for amotivation: “Performance management systems have taken away my previous motivation to be a better teacher,” whereby teachers who were overtly aware of the use of performance pay in their context appeared more likely to be amotivated. The post hoc Dunn-Bonferroni test suggested a statistically significant difference between those who identified as Yes and No (H = 31.558, P = 0.034) to performance pay being explicitly in use in their school (though it is worth noting again that No is technically incorrect in legislative terms). This outcome was not replicated across all variables measuring for amotivation, likely due to the multi-dimensional complexity of amotivation already noted (Cheon & Reeve, 2015; Legault et al., 2006; Markland & Tobin, 2004; Shen et al., 2010, 2013), but it is striking that this difference emerged for a variable measuring for amotivation that was most explicitly phrased in respect to performativity undermining teachers’ own values, leading to an absence of impetus or purpose. Given that this was most prominently the case in those contexts where performance pay is in explicit operation, it can be perhaps be inferred either that the overt use of performance pay is indicative of contexts which were already controllingly performative, or else such conditions were exacerbated or indeed initiated by the introduction of performance pay. Either way, it seems that there is a correlation between the employment of performance pay and teachers’ increased amotivation.

No significant differences emerged in respect to the various variables relating to school type, years’ service, roles and responsibilitie,s or gender, suggesting a commonality of perspective in terms of motivational dispositions.

4 Qualitative analysis: incentives, negative incentives, and emoluments

4.1 Incentives: “the carrot”

The first theme identified was that of positive incentivization, or the prospect of a future reward for enhanced performance. One way this theme was generated related to some teachers’ perceived hostility towards incentivization, with the “carrot” seen as actively demotivating: “Performance management is disrespectful. I want to be better because I want to be better. I don’t need the financial aspect to be dangled in front of me” (Gillian). In terms of identifying the reasons for this negative attitude towards the “carrot,” other participants’ comments were characterized by a sense of vocation which outweighed any financial incentive: “PRP (performance related pay) works in business when you are motivated to get more money” (Margaret). This first response pertains to the notion that such a system of reward might be antithetical to a more vocational profession. A similar, but subtly different sentiment was expressed as “Though pay is a driving factor in attending work, it is not a driving factor in my work performance” (Tommy). This articulates the idea that pay has traction in terms of employment, but not improvement. Collectively, these teachers perceived pay to have a lack of traction in respect to their motivation to improve as teachers.

Yet there was divergence from this view, with some positivity towards the “carrot” in evidence. For example, one participant perceived himself unmoved by punitive performance pay, but noted the appealing prospect of performance-enhanced pay, as opposed to performance-related pay: “Yeah. I think money is a great motivator” (Pete). Another professed they would be motivated by performance-enhanced pay, but only if it were based upon a holistic judgement:

If someone said to me, ‘I’m going to give you £10,000 extra because you’ve been an outstanding teacher and because you guide others, you coach others…but if they turned round and said, ‘I’m going to give you a £10,000 pay rise because of your results’, I think that’s wrong because every cohort is different. (Lee)

Related to this, a participant noted similar misgivings about performance pay being based upon unachievable criteria. These issues with consistent and fair judgement led her to the conclusion:

I completely don’t agree with it because there’s so many different set ups and context to classrooms and those stories aren’t always considered… and so for us to then have a performance pay related kind of conversation around that, I think that would be really unfair. (Grace)

By contrast, some teachers with fewer years’ service (but by no means all) seemed to perceive financial incentivization as a considerable attraction, perhaps expressive of a kind of mercenary syndrome, whereby performance pay induces such behaviors amongst staff:

A lot of what I do is dictated by appraisal and this is when I’m gonna sound slightly selfish because I want to progress financially. I want to move up and I want more money. (Ian)

This figure emphasized the idea of enhanced, rather than punitive performance pay, explicitly endorsing the “carrot,” rather than the stick. Yet this was not consistent amongst participants with fewer years’ service, with another stating it would not be motivating (though adding the ambiguous detail there was some sense of injustice):

I don’t think I’d be motivated by it. I know earlier last year I did have a bit of a conversation with someone who said I should be earning more than I did cos I earn the least in the entire department, yet I do essentially at one point the most (Natalie)

Indeed, even the previously quoted participant noted some room for doubt: “That’s the carrot. I want that carrot. That’s a nice carrot. That carrot would make me a little bit happier, assuming of course that money makes you happy” (Ian). The note of ambivalence at the end of this remark is worth pause, expressive of an uncertainty over whether monetary increase is synonymous with happiness.

For some, an interesting factor in respect to “the carrot” was identified as a lack of awareness of the policy, with teachers of varying years’ service unacquainted with the legislative change:

No, we’re just doing the old traditional going through the pay scales and as long as you do your pay scales you can work up but we’re still working on the accepted way the County recommends. (Lee)

There appears an issue with school hierarchies not articulating clearly the existence of performance pay (perhaps due to budget restraint or opposition to the policy). It is worth noting the responses of No and Don’t Know are technically incorrect (all school must have implemented it in some way as a requirement). Yet such an absence of clarity over performance pay as evident elsewhere: “I jumped up two pay scales last year, which I didn’t think could happen, but yeah. If they introduced accelerated pay, I quite like the idea of that” (Ian). What is intriguing here is that this same individual, when asked directly if his school operated performance pay said this was not the case, despite his being the beneficiary of accelerated financial advancement.

Another participant developed upon the idea of an interesting factor being the implementation of the policy in an era of budgetary restraint:

School strapped for cash so told head I’m not looking to go up the pay ladder next year. Jobs in local schools all offering no higher, so I think I’ve got a good deal. Despite doing 70 h last week. And being a so-called outstanding teacher. (Katie)

In this case, an element of the policy appears to be in operation, namely that progression is not automatically tied to years’ service. However, the participant appears to be unaware of her entitlement to progress (given the reference to an “outstanding” inspectorate grading).

For others, teachers who suggested that pay might incentivize, there was a sense this might be one motivation amongst others:

Definitely freedom to take hold of what you teach…the people I work with…the management team and how they value me, and yeah the pay would come in there as well (Amaya)

This was not solely a question of finding it difficult to disaggregate pay from other forms of motivation, but even to a certain degree noting a connectivity. This makes it challenging to analyze pay policy in isolation from other factors:

Teaching is a vocation…you certainly don’t do it for the money, but the money helps…I really do love the visions and the values…I think pay connects them, it’s the common factor or denominator…Yes, pay is in there. (Ian)

This is illustrative of the complex web of motivations that can exist within any profession (or indeed any individual). Pay, where it exhibits perceived traction as an incentive, is perhaps one impetus amongst many.

4.2 Negative incentives: “the stick”

A second theme salient in the qualitative data was “the stick,” defined as the use of performance-related pay in a punitive sense. Perhaps most compellingly, respondents offered descriptions of performance-related pay being used to actively preclude pay progression: “Performance Management Targets are used to PREVENT pay progression, not reward hard work” (Kath) and “School with financial problems - they will find any reason not to give raise” (Melanie).

While clearly related in part to perceived financial issues in schools, it is also possible some school hierarchies perceive punitive use of pay as a motivating factor. However, the accuracy and objectivity of performance assessment is salient here: “Performance related pay, based on students achieving unrealistic targets and data driven activities are certainly having a huge impact” (Joanna). Being subject to unfair judgements based on unachievable or inappropriate measures of effectiveness appeared to affect teachers’ motivations significantly. In other words, it seemed to result in disengagement, as opposed to increased impetus: “I was strongly advised not to apply…even though I achieved all my targets from my previous appraisal. I am now no longer teaching” (Mandy). In contrast with performance-enhanced pay, the demotivating nature of the punitive use of performance pay was emphasized by some, with one individual even describing collective pay punishment:

They put a ban on anybody moving up despite the fact that we could actually prove that we’d met the certain criteria…the school as a whole wasn’t delivering the correct grades and the correct grades A-C in terms of English and Maths…that’s probably the worst decision that they made. They lost their experienced teachers that were probably holding the school together to a certain extent. (Grace)

This was not confined to teachers with greater years’ service, however, as other participants describing a downward spiral that would result from pay as punishment, with a consequent impact on productivity and motivation:

I think if pay were to be dangled in front of you in that way you don’t meet this target then you lose X, Y, Z of your pay or whatever, that would be really de-motivating. I think it would make me think in a negative downward spiral. (Heather)

In sum, whilst pay as an incentive was recognized as a motivator by some, by contrast, pay as a punitive measure not only often lacked motivational traction, but proved actively demotivating.

4.3 Emoluments

The idea of an emolument is distinct from incentives/negative incentives as it represents a reward for services already rendered, as opposed to an incentive or negative incentive to perform better in the future. This suggests the idea that pay in this sense can be about maintaining motivation or encouraging retention, rather than a “carrot” as such: “if…pay reflected the work that we put in every day and the extra hours and the stresses that it can bring to your life” (Amaya). This sense of a reward commensurate to the extent of work already undertaken was articulated as pay which was proportionate, corresponding with the difficulty and scope of the work:

It would be nice if the pay reflected the amount of hours I put in (working over 12 hours most week days) but that would have little impact on my professional conduct. (Jimmy)

This comment was not in relation to future-orientated performance (indeed, the participant above explicitly excludes this). However, the sense of reward for work already undertaken may affect factors such as morale, with potential implications for future performance.

5 Synthesis of data strands

For the present study, there was considerable variation in perceptions of pay across all participants, with perceived traction for some, but not for others. Likewise, reports of inconsistent implementation of performance pay (including a lack of awareness of its existence in some cases) mean that discerning a general perspective amongst participants is compounded in difficulty. Similarly, these differences are not straightforward, as a person’s motivations can be multiple, complex, variable over time. and sometimes contradictory (or co-existing), points also noted by Heneman (1998) and Malen (1999). Thus, it could not be assumed there are stable types in relation to performance pay, compounding the difficulties associated with such a policy.

This acknowledged, there were a range of interesting points of convergence and divergence between the data strands. The use of incentives in the form of performance pay constituted a point of some divergence. The quantitative findings and open responses from the survey ranged from negative to mildly positive on performance pay, while the interviews indicated that it may possess more considerable motivational potency. There was a clear and open admission of pay as a strong potential motivator in some of the qualitative interviews. Yet these remarks were often accompanied by other comments pertaining to the difficulties associated with obtaining a fair and holistic judgement on pay progression. It may also be that the relatively small number of teachers interviewed possessed a disproportionate number of individuals motivated by pay, though this is conjectural. It could equally be that the format of qualitative interviews might allow both for more openness and probing on the subject of pay. At the same time, there were areas of alignment with the survey, with other teachers interviewed indicating they were not strongly motivated by financial reward.

Similarly, the notion of a positive sense of pay as an emolument (as opposed to an incentive) was relevant to all strands of the analysis. This included the survey (where a variable measuring for external regulation which explicitly referred to reward received a more slightly more positive response), as well as the open responses and the interviews. The distinction between an emolument (a just reward for services already rendered) and an incentive (a future-orientated inducement) is important, as some teachers appeared to be more in favor of an emolument than an incentive.

Another point of synthesis relates to the awareness of performance pay. There appears to be an issue in relation to school hierarchies not articulating the existence of performance pay to teachers, clearly evident across both the qualitative and quantitative data strands. This could be driven a range of factors, such as inconsistent or partial adoption of the policy across the national context in question, or perhaps as a consequence of an inherent absence in clarity as to the policy’s nature, or possible communication issues in given school contexts (or a combination of these and other factors).

In one final important sense, the different qualitative and quantitative analyses were in strong accord in respect to pay. A clearly negative view of punitive performance pay was reported by interviewees and in the open responses, according with the survey results. There was a clear sense of pay being reduced or salary progression being stalled on the basis of performance as something that would result in very considerable demotivation. Thus, the use of negative incentives was powerfully rejected by participants.

6 Discussion: carrot or stick? Or neither?

This discussion will explore performance pay as New Public Management in action. To reiterate, core definitional features of NPM include “explicit standards and measures of performance…output controls (resource allocation and rewards linked to measured performance)…private-sector styles of management practice… parsimony in resource use” (Hood, 1991, p.4–5) and “widespread use of data…test-based accountabilities…comparative-competitive frameworks” (Wilkins et al., 2019, p.147). This discussion will explore the extent to which these doctrinal components of NPM are at work and how they shape teachers’ responses to performance pay.

A first area for discussion relates to the inefficacy of negative incentives. Here, different doctrinal components of NPM can be seen as operating in combination as teachers are subject to the prospect of performance pay employed punitively, most especially teachers being made to compete for a limited and “parsimonious” resource allocation, as well as the emphasis on being held accountable for “poor performance.” In relation to studies such as Atkinson et al. (2009) which articulate the value of performance-related pay, rather than performance-enhanced pay, the present study identifies no evidence to support such a view, particularly given findings on the punitive use of performance pay. Thus, a crucial finding here for policy development would be the avoidance of the use of performance pay in a punitive fashion; pay being reduced or stalled on the basis of performance was regarded as a very considerable demotivation, a view also articulated by Mahony et al. (2004). This would also contrast with Heneman (1998, p.54) who found that “teachers did not report…fear of any formal negative sanctions for failing to meet the achievement goals.” Thus, the present study observes that punitive aspects of private-sector style pay management (implemented through NPM) are inefficacious or outright counterproductive in this context.

Another key facet of NPM is that of monetary reward, working on the private-sector premise that financial incentivization is a powerful inducement for improved performance. In addition, relevant here is NPM’s embrace of explicit standards—the use of “objective” measures of performance in order to determine reward. Insofar as performance-enhanced pay in the context of England is a potential incentive for some teachers, it seems to be regarded with considerable ambivalence and/or limited appeal (similar to Goldhaber et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2004) or only to the degree as Mintrop et al. (2018, p.306) found, that “the effect…is mixed and success is partial.” Those participant teachers who reported the attraction of performance-enhanced pay (not a universal view) were consistent in arguing the judgement should be holistic, as echoed by Malen (1999) and Smith and Holloway (2020), rather than based on numeric targets (and participants observed this was very difficult to achieve in practice, thus echoing Heneman’s (1998) findings). Thus, this finding would contrast with Liu et al. (2016), who found evidence supporting teachers’ confidence in student outcomes as a valid and important evaluation measure in a context of performance pay. Here, NPM’s emphasis on measurement is a major factor, specifically the use of quantitative success indicators as the primary (if not sole) “output control” (Hood, 1991, p.4–5) employed. This is perhaps especially problematic given the complexity of learning and its irreducibility to a simplistic “teaching quality = grade outcome” formulation, not least given the difficulties associated with defining effective performance in general terms (Proudfoot & Boyd, 2023), as well as contextual factors at play, such as economic deprivation (Lupton, 2014; Lupton & Thrupp, 2013; McKinney, 2014). This tension between quantitative targets and professional goals has been well-observed by Cutler and Waine (2000) and Smylie and Smart (1990), including “incongruities and tensions between merit pay and career ladder programs and beliefs and practices that characterize and govern teachers’ work” (Smylie & Smart, 1990, p. 139). Here, Conley and Odden’s (1995, p.233) observation that “policy analysts, then, should strategically consider how [a]…system of compensation might affect sacred norms of collegiality” seems especially pertinent, if performance pay undermines collaboration through the introduction of competition. Yet as competition is a key doctrinal aspect of New Public Management (the “comparative-competitive frameworks” articulated by Wilkins et al., 2019, p.147), it seems inevitable that such a damaging effect would occur in an environment where NPM is the policy orthodoxy. The present study similarly accords with Lundstrom (2012), who delineates teachers’ perspectives of perverse incentives leading to teaching to the test, as also articulated by others (for example, Parcerisa, 2020; Piattoeva, 2021). These features again correlate with New Public Management, as they are expressive of the “unintended” or “paradoxical” consequences which so often typify NPM (Hood & Peters, 2004, p.267); namely, that in the pursuit of performance, educational standards are in fact lowered. Corollaries with Lundstrom’s (2012) work would also include considerable reservations over consistency, transparency, and fair judgement expressed by participant teachers in the present research, issues that are also variously articulated by others (for example, DeSander, 2000; Firestone, 1991; Heneman and Milanowski, 1999; Malen, 1999; Pham et al., 2021; Springer et al., 2012). This is not only true of performance pay per se, but is also emblematic of NPM, as it aligns with other work (e.g., van der Sluis et al., 2017; Greany, 2020; Pagès, 2021) which shows the enactment of New Public Management is characterized by the absence of clarity and fairness (a point expanded upon below), with this most especially the case for those at an operational level (Hood, 1991), in this case, teachers.

The notion of a positive sense of pay as an emolument merits some pause. The distinction between an emolument (a just reward for services already rendered) and an incentive (a future-orientated inducement) is perhaps important, as some teacher participants appeared more in favor of an emolument than an incentive. Mintrop et al.’s (2018, p.299) observation of teachers’ perceptions of the “universal deservingness” of such rewards for all education professionals is relevant here. However, such an observation would still need to be located within a “NPM ideology centered on measured value for money” (Helgetun & Dumay, 2021, p.82). Whilst an emolument might be deployed post hoc (as opposed to a pre-determined incentive), it nonetheless creates an association between measurement and reward and is thus not without serious dangers. If assumptions around NPM are correct and the focus is on measurement rather than learning, the intended effect is not achieved.

This relates to the workability of NPM more broadly, and how “new public management regimes focus on raising standards and efficiency through mechanisms of competition, audit and performance management” (Kulz, 2021, p.99) which are “fraught, with significant implications for…coherence, equity and legitimacy” (Greany, 2020, p.1) when confronted with practical implementation. This is a view shared by van der Sluis et al. (2017, p.326) “NPM is often surrounded by an uncertainty by all of those involved” and Pagès (2021, p.557) who reports the “ambiguous mandate” created by New Public Management. Indeed, significant difficulties around implementation were noted even with the arguably relatively less complex precursor “Threshold” system in England (Storey, 2000). In sum, issues around workability mean implementation of the mechanisms noted by Kulz (2021), yet simultaneous negotiation of the (perhaps insurmountable) challenges described by Greany (2020). This is particularly the case for performance pay given that it is such a totemic and charged an aspect of NPM.

In terms of other implications for policy, it may be helpful to relate the findings to DfE’s (2019) stated guidance, with the assistance of the idea of “unintended consequences” whereby New Public Management “can unintendedly produce the opposite of the effect desired by their architects” (Hood & Peters, 2004: p.269). For example, the DfE’s twin aims that performance pay should be transparent in implementation and objective in judgement appear to be achieving the opposite effect, with participants reporting the absence of clarity and biased, unfair judgement. Similarly, DfE’s (2019) emphasis on proportionality, in the sense of measurement and evidencing not increasing teachers’ workloads, seems at odds with the perspectives of a substantial body of participants in this study (which instead accords with Humes (2021) on the burdens of bureaucracy). In one respect, however, they do appear to have met their stated intention. This is that they anticipated schools would adopt different approaches, which appears to be the case based on the present findings. However, the extent to which this is down to inconsistency of implementation, rather than a school’s thoughtful tailoring of policy to context is a not insubstantial question. This could be partly driven by Mintrop et al.’s (2018. p.303) idea that “school leaders, rather than risking conflict with their faculties, retreated from the idea of managing by incentives…[and] quietly distanced themselves.” This represents a significant area of challenge, given a centrally mandated policy which requires practical implementation at the local level. Indeed, perhaps of greatest relevance here is Wilkins et al. (2021) observation that the gap between strategic policy and enacted practice is a known feature of NPM and one which performance pay strongly encapsulates.

7 Conclusion

In terms of the specific implications for performance pay, this study sought to examine the views of working teachers in a context of major recent policy change, drawing conclusions significant both to the context itself and internationally. This study concludes that teachers perceive performance pay at best ambivalently, either due to an inherent lack of impetus, or, where perceived to be more appealing, due to the problematic practical implementation of such a model. Taken overall, there appear to be considerable difficulties associated with performance pay in respect to both theoretical principles and enacted practice. Importantly, the study demonstrates the clear need to seek out and understand teachers’ own perspectives on performance pay, examining the views of the supposedly incentivized.

Performance pay can be seen as a particularly emblematic manifestation of New Public Management, where characteristics such as measurement for comparative and competitive purposes, high-stakes accountability, and intensive managerialism are perhaps at their most nakedly exposed in a single policy. Given the totemic nature of performance pay, an empirical examination of its facets is thus powerfully demonstrative of the wider NPM agenda. Given the pervasive nature of NPM, such an example provides a writ-large illustration of the problematic and counterproductive nature of such an approach to management. Indeed, Hood and Peters (2004, p.272) assertion, “the harder we look, the more Mertonian the world of NPM seems likely to be” seems very true for the present study, with clearly unintended consequences in the form of “goal displacement” or “functional disruption” (Hood & Peters, 2004, p.271). But this article demonstrates not only the value of performance pay in understanding NPM more generally. Crucially, New Public Management represents a powerful lens for contextualizing performance pay, understanding its underlying principles and grasping its problematic enactment in practice.

8 Limitations and future research

The present study recommends further research on the extent to which teachers’ might be shaped longitudinally by performance pay policy. It might be suggested that teachers with fewer years’ service (and typically paid less) would be more responsive to incentivization, but this was not always apparent in the present findings. There was, however, evidence of a mercenary syndrome expressed by some early-career teachers in the qualitative strand (whereby beginning professionals are inculcated into such a view). This may in part be exacerbated by Jerrim’s (2020, p.19) observation that recently qualified teachers “feel undervalued and under-appreciated,” a view echoed in the American context by Ford et al. (2017). Hargreaves and Goodson (2006) have described how a given generation of teachers can be inculcated into a particular perspective or way of thinking by the dominant educational environment as they entered the profession (though they also argue that perspectives can be expressive of broader societal shifts in generational attitudes). Whether this mercenary syndrome is a growing trend could be of interest. Another separate recommendation would relate to sample size. This study offers rich data on performance pay and its significance to NPM, but more extensive studies would be recommended given the limited sample size of the present study. Finally, the idea of an emolument also perhaps warrants further examination. The present study anticipated views in respect to incentives and negative incentives, but the idea of the emolument was a surprising element in the data and would benefit further dedicated exploration.

Data availability

Data cannot be made available as permission was not sought from participants.

References

Apple, W. M. (2011). Democratic education in neoliberal and neoconservative times. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 21(1), 21–31.

Atkinson, A., Burgess, S., Croxson, B., Gregg, P., Propper, C., Slater, H., & Wilson, D. (2009). Evaluating the impact of performance-related pay for teachers in England. Labour Economics, 16(3), 251–261.

Bartlett, S. (2000). The development of teacher appraisal: A recent history. British Journal of Educational Studies, 48(1), 24–37.

Bates, A. (2012). Transformation, trust and the ‘importance of teaching’: Continuities and discontinuities in the coalition government’s discourse of education reform. London Review of Education, 10(1), 89.

Bazeley, P. (2012). Integrative analysis strategies for mixed data sources. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(6), 814–828.

Beck, J. (2008). Government professionalism: Re-professionalising or de-professionalising teachers in England? British Journal of Educational Studies, 56(2), 119–143.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brenner, M. (2006). Interviewing in educational research. In Green J., G. Camilli, P. Elmore, A. Skukauskaiti, & E. Grace (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research. E. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Carr, S. (2015). Motivation, educational policy and achievement: A critical perspective. Routledge.

Cheon, S. H., & Reeve, J. (2015). A classroom-based intervention to help teachers decrease students’ amotivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40, 99–111.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. RoutledgeFalmer.

Conley, S., & Odden, A. (1995). Linking teacher compensation to teacher career development. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 17(2), 219–237.

Cook, C., Heath, F., & Thompson, R. L. (2000). A meta-analysis of response rates in web- or internet-based surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(6), 821–836.

Courtney, S. J., & Gunter, H. M. (2015). Get off my bus! School leaders, vision work and the elimination of teachers. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(4), 395–417.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Cutler, T., & Waine, B. (2000). Mutual benefits or managerial control? The role of appraisal in performance related pay for teachers. British Journal of Educational Studies, 48(2), 170–182.

Dalton, P., & Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. (2011). If you pay peanuts do you get monkeys? A cross-country analysis of teacher pay and pupil performance. Economic Policy, 26(65), 5–55.

DeSander, M. K. (2000). Teacher evaluation and merit pay: Legal considerations, practical concerns. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 14(4), 307–317.

DfE. (2010). The importance of teaching: The Schools White Paper. Crown.

DfE. (2012). The education (school teachers’ appraisal) (England) regulations 2012. Crown.

DFE. (2019). Implementing your school’s approach to pay departmental advice for maintained schools and local authorities. Crown.

DFES. (2006). The education (school teacher performance management) (England) regulations. Crown.

Dunleavy, P., and Hood. C (1994). From old public administration to New Public Management. Public Money and Management, 14(3), 9–16.

Eren, O. (2019). Teacher incentives and student achievement: Evidence from an advancement program. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 38(4), 867–890.

Fernet, C., Senécal, C., Guay, F., Marsh, H., & Dowson, M. (2008). The work tasks motivation scale for teachers (WTMST). Journal of Career Assessment, 16(2), 256–279.

Firestone, W. A. (1991). Merit pay and job enlargement as reforms: Incentives, implementation, and teacher response. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 13(3), 269–288.

Firestone, W. A. (1993). Alternative arguments for generalizing from data as applied to qualitative research. Educational Researcher, 22, 16–23.

Ford, T. G., Van Sickle, M. E., Clark, L. V., Fazio-Brunson, M., & Schween, D. C. (2017). Teacher self-efficacy, professional commitment, and high-stakes teacher evaluation policy in Louisiana. Educational Policy (Los Altos Calif), 31(2), 202–248.

Fryer, R. G. (2011). Teacher incentives and student achievement: Evidence from New York City public schools. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(2), 373–407.

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204(6), 291–295.

Goldhaber, D., Bignell, W., Farley, A., Walch, J., & Cowan, J. (2016). Who chooses incentivized pay structures? Exploring the link between performance and preferences for compensation reform in the teacher labor market. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(2), 245–271.

Gorozidis, G., & Papaioannou, A. G. (2014). Teachers’ motivation to participate in training and to implement innovations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 39, 1–11.

Greany, T. (2020). Place-based governance and leadership in decentralised school systems: Evidence from England. Journal of Education Policy, 37(2), 1–22.

Gunter, H. M. (2008). Policy and workforce reform in England. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 36(2), 253–270.

Hall, D., & Gunter, H. (2016). England. The Liberal State: Permanent instability in the European Educational NPM Laboratory. In H. Gunter, E. Grimaldi, D. Hall, & R. Serpieri (Eds.), New Public Management and the reform of education: European lessons for Policy and Practice. Routledge.

Hargreaves, A., & Goodson, I. (2006). Educational change over time? The sustainability and non-sustainability of three decades of secondary school change and continuity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(1), 3–41.

Helgetun, J. B., & Dumay, X. (2021). From scholar to craftsperson? Constructing an accountable teacher education environment in England, 1976–2019. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 80–95.

Heneman, I. I. I., H. G (1998). Assessment of the motivational reactions of teachers to a school-based performance award program. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 12(1), 43–59.

Heneman, I. I. I., H. G., & Milanowski, A. T. (1999). Teachers attitudes about teacher bonuses under school-based performance award programs. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 12(4), 327–341.

Hill, A. J., & Jones, D. B. (2021). Paying for whose performance? Teacher incentive pay and the black–white test score gap. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 43(3), 445–471.

Hood, C. (1976). The limits of Administration. John Wiley.

Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19.

Hood, C. (2000). Paradoxes of public-sector managerialism, old public management and public service bargains. International Public Management Journal, 3, 1–22.

Hood, C., & Peters, G. (2004). The Middle Aging of New Public Management: Into the Age of Paradox? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14, 3.

Humes, W. (2021). The ‘iron cage’ of educational bureaucracy. British Journal of Educational Studies, 70(2), 235–253.

Jerrim, J. (2020). How is life as a recently qualified teacher? New evidence from a longitudinal cohort study in England. British Journal of Educational Studies, 69(1), 1–38.

Kelley, C. (1999). The motivational impact of school-based performance awards. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 12(4), 309–326.

Kulz, C. (2021). Everyday erosions: Neoliberal political rationality, democratic decline and the Multi-academy Trust. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(1), 66–81.

Kuzon, W. M., Urbanchek, M. G., & McCabe, S. (1996). The seven deadly sins of statistical analysis. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 37(3), 265–272.