Abstract

A multi-element and multi-phase internal oxidation model that couples thermodynamics with kinetics is developed to predict the internal oxidation behaviour of Fe–Mn–Cr steels as a function of annealing time and oxygen partial pressure. To validate the simulation results, selected Fe–Mn–Cr steels were annealed at 950 °C for 1–16 h in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and dew points of − 30, − 10 and 10 °C. The measured kinetics of internal oxidation as well as the concentration depth profiles of internal oxides in the annealed Fe–Mn–Cr steels are in agreement with the predictions. Internal MnO and MnCr2O4 are formed during annealing, and both two oxides have a relatively low solubility product. Local thermodynamic equilibrium is established in the internal oxidation zone of Fe–Mn–Cr steels during annealing and the internal oxidation kinetics are solely controlled by diffusion of oxygen. The internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels follows the parabolic rate law. The parabolic rate constant increases with annealing dew point, but decreases with the concentration of the alloying elements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advanced high-strength steels (AHSS) are extensively used for automotive applications to reduce the weight of car bodies and thereby reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions; see, for example, [1]. A zinc coating is applied onto the steel surface usually by hot-dip galvanizing [2] in order to protect the AHSS against corrosion. Before entering the zinc bath, the steel strip passes through continuous annealing furnaces. The annealing atmosphere is mostly a gas mixture of N2 and H2 with dew points ranging from − 60 to 10 °C, whose oxygen partial pressure level is below the dissociation oxygen partial pressure of Wüstite (FeO). However, oxidation of the alloying elements (e.g. Mn, Cr, Si, Al) in AHSS is thermodynamically favourable during annealing process prior to galvanizing. The presence of these alloying element oxides at the steel surface reduces the zinc wettability [3] and thus impairs the quality of the galvanized steel product [4]. Hence, understanding the nature of oxidation of AHSS and predicting the oxidation behaviour of AHSS are essential to the steel industry in terms of designing new steel grades and optimizing annealing parameters.

The transition from internal to external oxidation as well as the kinetics of internal oxidation of Fe–Mn binary steels has been studied extensively [5, 6]. It has been found that the internal oxidation behaviour of Fe–Mn binary steels can be well described by the classical Wagner internal oxidation theory [7]. Recently, the thermodynamics of oxides formation in Fe–Mn–Cr ternary and Fe–Mn–Cr-Si quaternary steels has been reported, and the type of oxides formed during annealing of Fe–Mn–Cr steels can be predicted as a function of alloy composition and oxygen partial pressure of annealing atmosphere [8]. However, the kinetics of internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels are not reported yet. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the kinetics of internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr ternary steels under different oxygen partial pressures below that of dissociation of Wüstite. The internal oxidation behaviour of selected Fe–Mn–Cr steels is first predicted by the newly developed coupled thermodynamic–kinetic internal oxidation model [9]. Then the predicted internal oxidation kinetics as well as the concentration depth profiles of internal oxides formed during oxidation are validated by comparison with experimental results.

Modelling of Internal Oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr Steels

The concentration depth profiles of internal oxide precipitates as well as the solute atoms in the Fe–Mn–Cr steels oxidized for different time and at different ambient oxygen partial pressures were simulated with a multi-element and multi-phase coupled thermodynamic–kinetic (CTK) internal oxidation model [9], which is built on a similar model involving external oxidation [10]. The details of this CTK model are described elsewhere [9]. The schematics of the internal oxidation model and the flowchart of the simulation program are displayed in Fig. 1. The alloy matrix is divided into a series of thin slices. Mass transport occurs between adjacent slices driven by the gradient of the chemical potential of each alloy constituent (i.e. alloying elements, iron and dissolved oxygen). Each slice is considered as a closed entity when conducting thermodynamic computation. At each time increment during oxidation, a two-step calculation procedure is executed. In the first step, the flux of each element between neighbouring slices is calculated and the change of the composition in each slice is obtained. In the second step, the thermodynamic equilibrium composition of each slice is calculated in terms of concentration of oxide precipitates and concentration of dissolved oxygen and alloying elements in the steel matrix. Thus, at each time step it is assumed that local thermodynamic equilibrium is instantaneously established between oxides, alloying elements and dissolved oxygen. This assumption is valid for the internal oxidation of Fe–Mn steels [11]. When annealing below dissociation oxygen partial pressure of Wüstite, the type of oxide phases formed in the Fe–Mn–Cr steels with the compositions used in this study is MnO and MnCr2O4 [8]. Hence, the precipitation of MnO and MnCr2O4 is considered in the simulations. The possible dissolution of Fe in MnO and MnCr2O4 is ignored. The amount of oxide precipitated in each slice and at each time increment is calculated considering mass balance and the solubility product, Ksp, of each oxide. The Ksp of MnO and MnCr2O4 is defined as, respectively:

where \(N_{\text{Mn}}\), \(N_{\text{Cr}}\) and \(N_{\text{O}}\) denote the local mole fraction of Mn, Cr and O dissolved in the alloy, respectively.

The change in Mn activity coefficient in austenite due to Cr addition is negligible according to thermodynamic computation [12]. Moreover, the effect of thermodynamic solute interaction between Mn and O on internal oxidation behaviour of Fe–Mn alloys is negligible [9]. Thus, the Fe–Mn–Cr steels can be considered as ideal solutions. Hence, the solubility product of MnO and MnCr2O4 as well as the diffusion coefficients of Mn, O and Cr in iron is considered as functions of temperature only, i.e. independent of local alloy composition. The diffusion coefficients of oxygen, Mn and Cr in austenite at 950 °C are: 3.5 × 10−7 [13], 4.0 × 10−12 [6] and 1.3 × 10−12 [14] cm2/s, respectively. The solubility products of MnO and MnCr2O4 in austenite at 950 °C are computed with a thermodynamic tool [12] and equal 2.4 × 10−10 and 3.0 × 10−39, respectively.

During oxidation, the surface of the steels is considered to be in equilibrium with the annealing atmosphere. The concentration of the oxygen dissolved at the surface of steels, which remains constant throughout the simulation, can be calculated as a function of temperature, the hydrogen volume fraction and dew point of the annealing atmosphere; see Appendix.

Experimental Procedures

Samples

The chemical compositions of the Fe–Mn and Fe–Mn–Cr steels are listed in Table 1. The steel samples were cut from hot-rolled steel plates by electric discharge machining (EDM). Before annealing, the surface of all specimens was grinded with SiC emery paper and then polished with 1-micron diamond grains. Next, the samples were cleaned ultrasonically in isopropanol and dried by a flow of pure nitrogen (purity better than 5 N). Finally, the samples were stored in airtight membrane boxes (Agar Scientific G3319, UK).

Annealing

The oxidation experiments were carried out in a horizontal quartz tube furnace (Carbolite MTF 12/38/850, UK) with tube inner diameter of 30 mm. The temperature in the furnace tube was measured with a NiCr/NiAl (type K) thermocouple at the sample location. A gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 passed the furnace tube at atmospheric pressure. Prior to admitting the gas mixtures to the furnace, the Ar and H2 gases (all with a purity better than 5 N) were filtered to remove any residual hydrocarbons, moisture and oxygen, with Accosorb (< 10 ppb hydrocarbons), Hydrosorb (< 10 ppb H2O) and Oxysorb (< 5 ppb O2) filters (Messer Griesheim, Germany), respectively. Deaerated and deionized water (18.2 MΩ cm at 25 °C) was evaporated with an in the gas line controlled evaporator mixer (CEM, Bronkhorst, The Netherlands) to create specific dew points of − 45, − 30, − 10 and 10 °C in the furnace. These dew points correspond to oxygen partial pressure of 8.1 × 10−22, 2.2 × 10−20, 1.0 × 10−18 and 2.3 × 10−17 atm. at 950 °C; see Appendix. The pure water was deaerated with nitrogen in a closed pressurized stainless-steel vessel, and the concentration of oxygen dissolved in the pure water was below 100 ppb, as measured with an O2 sensor (InPro 6850i, Mettler Toledo, USA). The dew points of − 10 and 10 °C were monitored with a cooled mirror analyser (Optidew, Michell Instruments, UK). The dew points of − 45 and − 30 °C were monitored with another cooled mirror analyser (S4000 TRS, Michell Instruments, UK). The fluctuation of dew points during annealing was within ± 2 °C. The partial pressure of evaporated H2O in the gas mixture is related to dew point according to the formula given in Appendix. The flow of each gas was regulated and monitored using mass flow controllers (Bronkhorst, The Netherlands). The flow rate of gas mixture with dew points of − 30–10 °C was 1500 sccm, while the flow rate of gas mixture with dew points of − 45 was 3000 sccm. Before annealing, the sample was placed onto a quartz boat located at the cold zone of the furnace tube. Then, the furnace was closed and flushed with the Ar + 5 vol% H2 gas mixture for more than 30 min. Next, the sample was moved to the hot zone of the furnace with a quartz rod to start an annealing cycle. The annealing times were 1, 4 and 16 h. At the end of the annealing cycle, the sample was moved in the reverse direction to the cold zone of the furnace tube. The heating and cooling of the sample were relatively fast, about 140–180 °C/min.

Characterization

X-ray diffractometry (XRD) was used to identify the oxide phases formed in the steel alloys after annealing. The XRD patterns were recorded, with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer in the Bragg–Brentano geometry using Co Kα radiation, in the 2θ region between 10 and 110° with a step size of 0.034° and a dwell time of 4 s. The depth below the surface corresponding with 70% of the diffracted intensity of pure iron is about 2.3–6.7 μm for 2θ from 20° to 60° [15].

The surfaces and cross sections of the annealed samples were observed with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a JSM-6500F (JEOL, Japan) operated with an accelerating voltage of 5 and 15 kV, respectively. X-ray microanalysis (XMA) using energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was performed with the same SEM instrument, but equipped with an UltraDry 30 mm2 detector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to determine the chemical composition of oxides qualitatively. The depth of internal oxidation zone was measured with SEM on backscattered electron images of cross section of oxidized samples. The volume fraction of internal oxide precipitates was determined from the backscattered electron images of cross section of oxidized samples using the image processing software ImageJ (version 1.47 s).

The concentration of Fe, Mn, Cr and O was determined with electron probe X-ray microanalysis (EPMA) using a JXA 8900R (JEOL, Japan) microprobe employing wavelength dispersive spectrometry (WDS). A focussed electron beam was used with an energy of 10 keV and a current of 50 nA. The composition at each analysis location of the sample was determined using the X-ray intensities of the constituting elements after background correction relative to the corresponding intensities of reference materials. In this case, the X-ray intensities of Fe-Kα, Mn-Kα, Cr-Kα and O-Kα were measured and pure Fe, Mn, Cr and SiO2 were used as references. The thus obtained intensity ratios were processed with a matrix correction program CITZAF [16]. The concentration depth profiles of Mn, Cr and O were determined from the cross section of the oxidized samples. An average concentration of each element at each depth was obtained from a line parallel to the sample surface consisting of 40 measurement points. The distance between adjacent measurement points was 1 μm. The distance between the adjacent lines (i.e. at different depths) parallel to the sample surface was also 1 μm. In order to prevent carbon contamination, an air jet cleaning the surface was employed during the EPMA measurements.

Results and Discussion

Transition from External to Internal Oxidation

Increasing the oxygen partial pressure in the annealing atmosphere (i.e. the dew point) promotes the internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels. Figure 2 shows the backscattered electron images of the surface and cross section of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel annealed at 950 °C for 16 h in the gas mixture with dew points ranging from − 45 to 10 °C. When annealing at a dew point of − 45 °C, the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel is externally oxidized, since the oxides are mainly formed at steel surface. The transition from external to internal oxidation of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel occurs at an annealing dew point of − 30 °C, with oxides formed both at steel surface and in the alloy matrix. The Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel is internally oxidized when annealed at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C. The observed microstructure and oxidation mode of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.0Cr steel after annealing is similar as that of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel. According to the results of XRD and XMA, the oxide formed during annealing at a dew point of − 45 °C is the (Mn,Cr,Fe)3O4 spinel, while annealing at dew points of − 30, − 10 and 10 °C forms both the (Mn,Cr,Fe)3O4 spinel and (Mn,Fe)O at the steel surface and as internal precipitates. The type of oxide species identified in the Fe–Mn–Cr steels annealed at dew points from − 45 to 10 °C is in agreement with the phase diagrams and experimental results reported in Ref. [8]. Lowering the dew point of the annealing atmosphere reduces the inward flux of oxygen and favours the outward diffusion of the oxidizing alloying elements and thus promotes the enrichment of oxides within internal oxidation zone. Adopting the extended Wagner internal oxidation theory for ternary alloys (see section “Kinetics of internal oxidation”), the calculated theoretical volume fractions of internal oxides in the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steels are 0.48, 0.18, 0.09 and 0.07 when annealing at dew points of − 45, − 30, − 10 and 10 °C, respectively. Taking the critical volume fraction of oxides for transition from internal to external oxidation as 0.2 [5], the predicted oxidation modes of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steels annealed at different dew points are in agreement with the experimental observations. Annealing Si free Fe–Mn–Cr ternary alloys does not form internal oxides along grain boundaries [17]. However, the Fe–Mn–Cr steel samples used in this study contain 0.1 at.% Si (see Table 1), and the formation of internal (Mn,Fe)2SiO4 and (Mn,Cr,Fe)3O4 along grain boundaries was observed; see Fig. 2. The penetration depth of oxides along grain boundaries is much larger (by a factor of 2 and more) than that of internal oxides formed inside grains.

SEM backscattered electron images of surface and cross section of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steels annealed for 16 h at 950 °C in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and dew points of − 45, − 30, − 10 and 10 °C. The Fe–Mn–Cr steels are internally oxidized above annealing dew point of − 30 °C. The Si impurity in the steels leads to the formation of (Mn,Fe)2SiO4 and (Mn,Cr,Fe)3O4 along grain boundaries

Concentration Profiles

The Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel is used as an example here to study the concentration profiles after oxidation, because this sample contains the highest amount of Cr. Figure 3 shows the simulated concentration profiles of internal MnO and MnCr2O4 precipitates as well as the Mn, Cr and O dissolved in iron matrix after annealing a Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr alloy at 950 °C for 16 h in the gas mixture with a dew point of 10 °C. The formation of an internal oxidation zone of MnO and MnCr2O4 beneath the steel surface is predicted, which agrees with the experimental observation; see Fig. 2. The concentrations of internal MnO and MnCr2O4 are almost constant in the internal oxidation zone and drop sharply to zero. The width of the internal oxidation zone of MnO is almost the same as that of MnCr2O4. Mn and Cr in the iron matrix are depleted within the internal oxidation zone, while their concentrations increase to bulk values beyond the internal oxidation front. The concentration profiles of MnO, MnCr2O4 and solute Mn and Cr as shown in Fig. 3 indicate that both MnO and MnCr2O4 are oxides with a low solubility product [6, 18]. The concentration of the oxygen dissolved in iron matrix decreases almost linearly with the depth below the surface to practically zero at internal oxidation front.

The simulated concentration profile of oxygen in the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel annealed at dew point of 10 °C is in good agreement with the experimental results; see Fig. 4. Since the concentration of solute oxygen in the iron matrix (maximum 3.6 ppm, see Fig. 3) is much below the detection limit of EPMA, the measured oxygen concentration reflects that of internal oxides. Once the ratio of MnO to MnCr2O4 concentration is known (see below), the volume fraction of internal oxides at each depth can be estimated from the oxygen concentration measured with EPMA, taking the molar volume of iron, MnO and MnCr2O4 as 7.1, 13.1 and 45.0 cm3/mol, respectively. The profile of the volume fraction of internal oxides determined by image analysis agrees with that obtained from the EPMA measurement; see Fig. 5. Both the results of the EPMA measurement and the image analysis show that the concentration of oxide precipitates is almost constant in the internal oxidation zone and drops sharply to zero at a depth of about 17 μm; see Figs. 4b and 5. Although the volume fractions (concentrations) of internal oxides at different depths are almost the same, the size of the oxide precipitate increases while the number density decreases with depth; see Fig. 4a. This is due to the fact that the driving force for oxide precipitation at internal oxidation front decreases with the width of the internal oxidation zone, as has been explained in details in the work of Bohm and Kahlweit [19]. The change in the size and number density of oxide precipitates with depth while maintaining an almost constant oxide concentration also indicates that during 16 h oxidation of the Fe–Mn–Cr steels the precipitation of MnO and MnCr2O4 (reaction between solute O, Mn and Cr) at internal oxidation front is fast compared with the progression of internal oxidation front, and thus, the local thermodynamic equilibrium is likely established during the internal oxidation process. The increase in the size and the decrease in the number density of oxide precipitates with depth are also observed for internal oxidation of Fe-7 at.% Mn binary steels [5].

a SEM image (backscattered electrons) of the cross section of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel where EPMA measurements were performed, and b simulated and measured (with EPMA) profiles of total oxygen concentration (oxygen in oxides and iron matrix) in the steel, after annealing for 16 h at 950 °C in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and a dew point of 10 °C. The dashed line indicates the internal oxidation front observed

Simulated and measured profiles of the volume fraction of internal oxides in the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel after annealing for 16 h at 950 °C in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and a dew point of 10 °C. The dashed line indicates the internal oxidation front observed; see Fig. 4a

Since the solubility products of MnO and MnCr2O4 are low, the concentrations of both Mn and Cr that remain in the alloy matrix within the internal oxidation zone can be neglected; see Fig. 3b. Hence, the Mn and Cr detected with EPMA within the internal oxidation zone are those present in the oxide precipitates. Since Cr only exists in the MnCr2O4 spinel and the molar ratio of Mn to Cr in MnCr2O4 is 1:2, the concentration of MnO and MnCr2O4 at each depth of the oxidized Fe–Mn–Cr steels can be evaluated from the measured concentration of Mn and Cr with EPMA within the internal oxidation zone. The experimental results show that the concentration of each type of oxides (i.e. MnO and MnCr2O4) within the internal oxidation zone of the annealed Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel is almost constant with depth, in agreement with the above predictions; see Fig. 6. The concentration ratio of MnO to MnCr2O4 is almost a constant and equal to 3:2 within the internal oxidation zone; see Fig. 6b. The experimental results confirm the prediction that the penetration depth of internal MnO is almost the same as that of MnCr2O4 for internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels; see Figs. 3a and 6.

a Simulated and measured (EPMA) concentration profiles of internal MnO and MnCr2O4, and b the corresponding ratio of concentration of MnO to MnCr2O4 as a function of depth in the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel after annealing for 16 h at 950 °C in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and a dew point of 10 °C. The dashed line indicates the internal oxidation front observed; see Fig. 4a

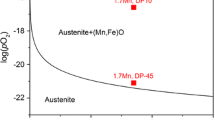

The oxygen concentration within the internal oxidation zone can also be evaluated from the measured concentrations of Mn and Cr with EPMA considering the stoichiometry of MnO and MnCr2O4 and also that all Mn and Cr within the internal oxidation zone are oxidized. However, the evaluated oxygen concentration based on Mn and Cr concentration is slightly lower than the oxygen concentration directly obtained from EPMA; see Fig. 4b. This is caused by the dissolution of Fe in the internal MnO and MnCr2O4 particles to form (Mn,Fe)O and (Mn,Cr,Fe)3O4 oxide solutions, respectively [8, 11]. For example, at 950 °C and with an oxygen partial pressure of 2.3 × 10−17 atm. (corresponding to the gas mixture with a dew point of 10 °C), the Fe fraction in cations of (Mn,Fe)O and (Mn,Cr,Fe)3O4 for a Fe–Mn–Cr alloy system at equilibrium is about 0.31 and 0.12, respectively, and the amount of Fe in both oxides increases with the oxygen partial pressure [8]. The concentration profile of solute oxygen within the internal oxidation zone of the annealed Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel decreases with depth below the surface; cf. Fig. 3b. The corresponding profile of oxygen activity expressed in terms of the logarithm of oxygen partial pressure (in atm.) is then obtained adopting Sievert’s law [11]; see Fig. 7a. Next, the Fe concentration in (Mn,Fe)O and (Mn,Cr,Fe)3O4 as a function of oxygen partial pressure in a Fe–1.9 at.% Mn–1.6 at.% Cr alloy system at equilibrium is computed with a thermodynamic tool [12]. Then, the estimated amount of excess oxygen consumed by Fe at each depth is obtained, considering that the concentration ratio of MnO to MnCr2O4 is 3:2; see above. Figure 7b shows the predicted and measured ratio of the total concentration of precipitated oxygen to that of oxygen consumed by Mn and Cr as a function of depth in the annealed Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel alloy. Both predicted and experimental results show the trend that the concentration of Fe in the internal oxides decreases with depth to almost zero near the internal oxidation front.

a Predicted profiles of solute oxygen concentration and the corresponding oxygen activity (expressed as oxygen partial pressure on logarithm scale) within the internal oxidation zone, and b profiles of predicted and measured ratio of the total precipitated oxygen concentration to the concentration of oxygen consumed by Mn and Cr, in the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel after annealing for 16 h at 950 °C in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and a dew point of 10 °C. The dashed line indicates the internal oxidation front observed; see Fig. 4a

The predicted and measured profiles of internal oxide volume fraction are in reasonable agreement for the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel annealed in the gas mixture with a dew point of − 10 °C; see Fig. 8. According to the EMPA results, the size of the internal oxidation zone of MnO is close to that of MnCr2O4. The measured concentration of internal oxides within the internal oxidation zone of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel annealed at a dew point of − 10 °C is still almost constant and decreases sharply to zero at the internal oxidation front. A relatively sharp internal oxidation front can also be observed from the SEM images. Thus, the depth of internal oxidation zone in Fe–Mn–Cr steels annealed at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C can be determined precisely, and the kinetics of internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels can be quantified accurately.

a SEM backscattered electron image of the cross section of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel at the location where EPMA measurements were performed, and b simulated and measured (EPMA) profiles of volume fraction of internal oxides in the steel, after annealing for 16 h at 950 °C in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and a dew point of − 10 °C. The dashed line indicates the internal oxidation front observed

Kinetics of Internal Oxidation

The measured kinetics of internal oxidation of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel annealed at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C are in good agreement with the predictions using the coupled thermodynamic–kinetic model; see Figs. 5, 8 and 9. The growth of internal oxidation zone of Fe–Mn–Cr steels during annealing follows the parabolic rate law (see Fig. 9), which can be described as:

where \(\xi\) is the depth of internal oxidation zone, t is oxidation time, and kp is the parabolic rate constant. Hence, the internal oxidation kinetics of Fe–Mn–Cr steels are solely controlled by diffusion of the reacting elements (i.e. O, Mn and Cr), while the precipitation of internal oxides can be considered to occur instantaneously. Therefore, local thermodynamic equilibrium between oxides and solute elements (O, Mn and Cr) in alloy matrix within internal oxidation zone is established during internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels. The parabolic growth behaviour of internal oxidation zone also shows that the Fe–Mn–Cr steel surface is in equilibrium with gas ambient during annealing, i.e. the concentration of oxygen dissolved at steel surface is constant with annealing time. Moreover, as discussed in the previous section, both MnO and MnCr2O4 have a relatively low solubility product and the size of internal oxidation zone of MnO is similar to that of MnCr2O4 when annealing at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C. Hence, the analytical approach using the extended Wagner internal oxidation theory for ternary alloys [20] is applicable for estimating the kinetics of internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels annealed above a dew point of − 10 °C. The parabolic rate constant kp is given by:

where \(\gamma\) is a dimensionless parameter and \(D_{\text{O}}\) is the diffusion coefficient of oxygen in alloy matrix. The value of \(\gamma\) can be obtained by solving the following equation [20]

where \(N_{\text{O}}^{\text{s}}\) is the mole fraction of oxygen dissolved at steel surface, \(N_{\text{Mn}}^{0}\) and \(N_{\text{Cr}}^{ 0}\) are the mole fraction of the solute Mn and Cr in the bulk alloy, \(D_{\text{Mn}}\) and \(D_{\text{Cr}}\) are the diffusion coefficient of Mn and Cr in the alloy matrix, and \(\nu\) and \(w\) are the oxygen-to-metal ratio of MnO and Cr2O3 (i.e. \(\nu = 1\), \(w = 1.5\)), respectively. Although MnCr2O4 is actually formed instead of Cr2O3 during annealing of Fe–Mn–Cr steels, the amount of oxygen consumed by oxidizing one mole of Cr equals 1.5 mol O. \(G(r)\) and \(F(r)\) are two auxiliary functions, which reads:

When the permeability [14] of oxygen is much higher than that of Mn and Cr, i.e. \(N_{\text{O}}^{\text{s}} D_{\text{O}}\,{>}{>}\,N_{\text{Mn}}^{0} D_{\text{Mn}}\) and \(N_{\text{O}}^{\text{s}} D_{\text{O}}\,{>}{>}\,N_{\text{Cr}}^{0} D_{\text{Cr}}\), Eq. (4) can be simplified and \(\gamma\) can be approximated as:

The experimentally determined parabolic rate constants for internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels are in good agreement with the calculated results using the extended Wagner approach [20]; see Table 2. The parabolic rate constants obtained from Eqs. (4) and (6) are almost the same (see Table 2), which indicates that the permeability of oxygen is much higher than the permeability of Mn and Cr for the steels studied here when annealing at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C. Hence, the kinetics of internal oxidation of the Fe–Mn and Fe–Mn–Cr steels annealed at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C are dominated by the bulk alloy composition and the oxygen permeability; see Eqs. (3) and (6). Adding Cr to the Fe–Mn steels decreases the internal oxidation rate simply because of the consumption of solute oxygen by forming MnCr2O4. The growth rate of internal oxidation zone increases with ambient oxygen partial pressure (i.e. annealing dew point) because the inward oxygen flux increases with the concentration of oxygen dissolved at steel surface.

The extended Wagner internal oxidation theory also allows estimating the degree of enrichment of the reactive alloying elements (in the form of oxides) in the internal oxidation zone [20]. The degree of enrichment of Mn (\(\alpha_{\text{Mn}}\)) and Cr (\(\alpha_{\text{Cr}}\)) is given by:

and

where \(N_{\text{MnO}}\) and \(N_{{{\text{MnCr}}_{ 2} {\text{O}}_{ 4} }}\) are the mole fraction of internal MnO and MnCr2O4, respectively. For example, the values of \(\alpha_{\text{Mn}}\) and \(\alpha_{\text{Cr}}\) calculated with the extended Wagner approach for the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel annealed at a dew point of 10 °C are 1.12 and 1.05, respectively, which are almost the same as the simulation results; cf. Fig. 3. The values of \(\alpha_{\text{Mn}}\) and \(\alpha_{\text{Cr}}\) are close to unity, indicating that the enrichment of each reactive element in the internal oxidation zone is small due to the high oxygen permeability. The mole fractions \(N_{\text{MnO}}\) and \(N_{{{\text{MnCr}}_{ 2} {\text{O}}_{ 4} }}\) can be obtained from the degree of enrichment of the two reactive elements according to Eqs. (7) and (8). Then, the volume fraction of oxides (f) within the internal oxidation zone can be estimated according to:

where \(V_{\text{MnO}}\), \(V_{{{\text{MnCr}}_{ 2} {\text{O}}_{ 4} }}\) and \(V_{alloy}\) are the molar volumes of MnO, MnCr2O4 and the alloy matrix, respectively.

However, the extended Wagner approach may not be valid for estimating the internal oxidation kinetics of Fe–Mn–Cr steel alloys annealed at a dew point of − 30 °C, because MnO and MnCr2O4 have different internal oxidation fronts. According to the simulation results, the depth of the internal oxidation zone of MnCr2O4 is about two times larger than that of MnO after annealing at a dew point of − 30 °C for 16 h; see Fig. 10b. Thus, the measured internal oxidation kinetics of Fe–Mn–Cr steels annealed at a dew point of − 30 °C were only compared with the simulation results. The measured depth of internal oxidation zone (inside grains) in the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel annealed for 16 h at a dew point of − 30 °C is about 3.4 μm, which is in fair agreement with our prediction; see Fig. 10.

a SEM image (backscattered electrons) of the cross section of the Fe–1.9Mn–1.6Cr steel and b simulated concentration profiles of internal oxides and precipitated oxygen in the steel, after annealing for 16 h at 950 °C in a gas mixture of Ar with 5 vol% H2 and a dew point of − 30 °C. The dashed line indicates the internal oxidation front observed

The good agreement between the measured and predicted kinetics of internal oxidation of Fe–Mn [6] and Fe–Mn–Cr steels annealed at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C shows that both the numerical simulation and the analytical approach based on the extended Wagner theory using the values of oxygen diffusivity [13] and oxygen dissolution [21] in austenite can be applied to these steels.

Conclusions

The coupled thermodynamic kinetic model allows prediction of the internal oxidation behaviour of Fe–Mn–Cr steels annealed under different ambient oxygen partial pressures, including the growth kinetics of internal oxidation zone and the concentration profiles of multiple internal oxides. The internal oxidation rate of Fe–Mn–Cr steels is controlled by the diffusion of reactants through the iron matrix and thus follows the parabolic rate law. Both MnO and MnCr2O4 exhibit a relatively low solubility product, while local thermodynamic equilibrium is established during internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steels. When annealing at dew points of − 10 and 10 °C, the depth of the internal oxidation zone of MnO is almost the same as that of MnCr2O4.

References

N. Fonstein, Advanced High Strength Sheet Steels, (Springer, Switzerland, 2015).

A. R. Marder, Progress in Materials Science 45, 2000 (191).

G. M. Song, T. Vystavel, N. van der Pers, J. T. M. De Hosson and W. G. Sloof, Acta Materialia 60, 2012 (2973).

E. M. Bellhouse and J. R. McDermid, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 41, 2010 (1539).

V. A. Lashgari, C. Kwakernaak and W. G. Sloof, Oxidation of Metals 81, 2014 (435).

V. A. Lashgari, G. Zimbitas, C. Kwakernaak and W. G. Sloof, Oxidation of Metals 82, 2014 (249).

C. Wagner, Zeitschrift Fur Elektrochemie 63, 1959 (772).

W. Mao and W. G. Sloof, accepted by Oxidation of Metals.

W. Mao and W. G. Sloof, in preparation.

T. J. Nijdam and W. G. Sloof, Acta Materialia 56, 2008 (4972).

W. Mao and W. G. Sloof, Scripta Materialia 135, 2017 (29).

C. W. Bale, E. Bélisle, P. Chartrand, S. A. Decterov, G. Eriksson, A. E. Gheribi, et al., Calphad 54, 2016 (35).

J. H. Swisher and E. T. Turkdoga, Transactions of the Metallurgical Society of AIME 239, 1967 (426).

D. J. Young, High Temperature Oxidation and Corrosion of Metals, (Elsevier, Oxford, 2008).

B. D. Cullity and S. R. Stock, Elements of X-ray Diffraction, 3rd ed, (Prentice Hall, New York, 2001).

J. T. Armstrong, Electron Probe Quantitation, (Springer, Boston, 1991).

Y. Ma, Kinetics of internal oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr steel alloys, Master thesis, (Delft University of Technology, 2017).

E. K. Ohriner and J. E. Morral, Scripta Metallurgica 13, 1979 (7).

G. Bohm and M. Kahlweit, Acta Metallurgica 12, 1964 (641).

Y. Niu and F. Gesmundo, Oxidation of Metals 60, 2003 (371).

V. A. Lashgari, Internal and External Oxidation of Manganese in Advanced High Strength Steels, Ph.D. thesis, (Delft University of Technology, 2014).

D. Huin, P. Flauder and J. B. Leblond, Oxidation of Metals 64, 2005 (131).

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out under Project Number M22.3.11439 in the framework of the research programme of the Materials innovation institute (M2i). Financial support from International Zinc Association (IZA) for Programme ZCO-62 is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are indebted to Dr. W. Melfo of Tata Steel (IJmuiden, The Netherlands) for providing the steels and the composition analysis. The authors are also grateful to Ing. J.C. Brouwer and Ing. C. Kwakernaak for technical support and assistance with experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The relation between dew point (DP) and partial pressure of water vapour (\(p_{{{\text{H}}_{2} {\text{O}}}}\)) was adopted from Ref. [22]:

where the units of \(p_{{{\text{H}}_{2} {\text{O}}}}\) and DP are in atmosphere (atm.) and degree Celsius (°C), respectively. Then, the partial pressure of oxygen (pO2, in atm.) at equilibrium can be calculated with the Gibbs free energy of formation of water vapour, namely [22]:

where T is absolute temperature and \(p_{{{\text{H}}_{2} }}\) is the partial pressure of H2 in atm.

For the concentration of oxygen dissolved at the surface (\(N_{\text{O}}^{\text{s}}\), in mole fraction) of iron with a fcc crystal lattice in equilibrium with ambient gas mixture, it holds that [21]:

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mao, W., Ma, Y. & Sloof, W.G. Internal Oxidation of Fe–Mn–Cr Steels, Simulations and Experiments. Oxid Met 90, 237–253 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11085-018-9836-7

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11085-018-9836-7