Abstract

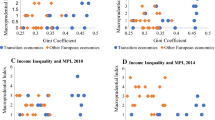

This paper examines the redistributive effects of financial liberalization, including domestic and external finance reforms, implemented in 64 emerging and low-income countries over the past four decades. To identify these effects, we employ a “doubly robust” estimation approach and generate impulse responses using the local projections method. Our findings reveal that financial reforms significantly reduce income inequality. These results are robust and hold across various specifications and alternative methods. We find that reducing income inequalities through financial reforms depends on several factors, including improved access to financial services, level of public expenditures, and institutional quality. Furthermore, we demonstrate that governments adopting a reform approach that considers sequencing and potential complementarity of measures can significantly reduce income inequality. Taking the business cycle into account, we observe that implementing financial reforms during periods of relatively slower economic growth would be more beneficial for developing countries. Financial reforms have an impact on reducing income inequality by increasing the income of individuals located at the bottom of the distribution while decreasing the income of individuals located at the top of the distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data used in this study, with the exception of the data on structural reforms, are sourced from public sources and are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

The concept of inequality, as defined by KNBS and SID (2013), pertains to the degree of variance between the distribution of economic well-being produced within an economy and the hypothetical equitable allocation among its populace. Recognizing the multidimensional nature of inequality, which encompasses disparities in access to fundamental services, opportunities, income, education, etc., this investigation specifically addresses the domain of income inequality.

Ostry et al. (2009) analyzes the impact of a sequencing strategy or complementarity of structural reforms on economic growth.

Furthermore, we conduct a thorough analysis to test the reliability of our findings by employing an alternative approach as defined by Alesina et al. (2020) to identify episodes of reform. This approach involves identifying episodes as those in which the absolute annual alterations in the reform indexes surpass the \(75^th\) percentile across the sample.

This observation aligns with the depiction of reform episodes using definitions from Alesina et al. (2020), wherein an episode involves a financial reform index exceeding the average annual change over all observations by two standard deviations or using the Kaopen indicator.

Refer to Fig. A2 in the Appendix Online for a visual representation of the diminishing relationship between financial reforms (domestic and external finance) and income inequality (Gini index).

However, it’s worth noting that local projection methods do have certain drawbacks in terms of efficiency.

Notably, the number of lag terms is determined based on the economic literature regarding the use of local projection methods, with a maximum autocorrelation lag set at \(h+1\).

An alternative choice is the enhanced inverse probability weighted (AIPW) estimator. This estimator includes an adjustment term that corrects for bias in the IPW estimator. Consequently, if the treatment model is accurately defined, the bias correction term becomes zero, rendering the estimator identical to the IPW estimator. In instances where the treatment model is improperly specified but the outcome model is correctly specified, the bias correction term fine-tunes the estimator. Notably, the inclusion of the bias correction term confers upon the AIPW estimator the same dual robustness attribute as the IPWRA estimator.

This approach may not be the most robust identification strategy, but it can serve as a starting point for developing one.

Qualitatively, in terms of the intensity of the estimated effects, we observe that the size of the estimated effects for domestic financial reforms, when used in continuous form, is relatively larger compared to those of external capital account liberalization reforms. However, quantitatively, Alesina et al. (2020) argue that it is not possible to compare reform indices across different sectors.

It’s important to note that achieving perfect alignment of covariates through conventional models like probit and logit is exceedingly rare.

These reform variables are incorporated as continuous variables rather than dummy variables. Nevertheless, when introduced as dummy variables according to the definition of reform episodes, the outcomes remain consistent with the baseline findings.

Similar to the Gini index, a lower Theil index signifies lower income inequality.

The calculation of the output gap relies on the approach outlined by Hamilton (2018), which employs the logarithm of GDP per capita. While conventional empirical practices often use the Hodrick-Prescott filter (Hodrick and Prescott 1997), this entails selecting a parameter value, a choice that warrants discussion. In contrast, we adopt the alternative method put forth by Hamilton (2018), which obviates the need for parameter selection and avoids the results’ sensitivity to the chosen parameter value.

The data is obtained from https://data.imf.org/?sk=f8032e80-b36c-43b1-ac26-493c5b1cd33b

If this volatility results in an inefficient allocation of resources, it is preferable to reform the domestic financial sector prior to opening the external capital account, rather than following a reverse sequencing strategy. By adopting this approach, higher economic growth can be expected (Ostry et al. 2009).

References

Abiad A, Oomes N, Ueda K (2008) The quality effect: Does financial liberalization improve the allocation of capital? J Dev Econ 87(2):270–282

Agnello L, Mallick SK, Sousa RM (2012) Financial reforms and income inequality. Econ Lett 116(3):583–587

Alemán JA (2011) Cooperative institutions and inequality in the oecd: bringing the firm back in. Soc Sci Q 92(3):830–849

Alesina AF, Furceri D, Ostry JD, Papageorgiou C, Quinn DP (2020) Structural reforms and elections: Evidence from a world-wide new dataset. Tech. rep, National Bureau of Economic Research

Ang JB (2010) Finance and inequality: the case of india. South Econ J 76(3):738–761

Aristei D, Perugini C (2014) Speed and sequencing of transition reforms and income inequality: A panel data analysis. Rev Income Wealth 60(3):542–570

Astarita C, D’Adamo G et al (2017) Inequality and structural reforms: Methodological concerns and lessons from policy. Tech. rep, Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European

Asteriou D, Dimelis S, Moudatsou A (2014) Globalization and income inequality: A panel data econometric approach for the eu27 countries. Econ Model 36:592–599

Barlow D, Radulescu R (2005) The sequencing of reform in transition economies. J Comp Econ 33(4):835–850

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2007) Finance, inequality and the poor. J Econ Growth 12(1):27–49

Bernal-Verdugo LE, Furceri D, Guillaume D (2013) Banking crises, labor reforms, and unemployment. J Comp Econ 41(4):1202–1219

Blanchard O, Giavazzi F (2003) Macroeconomic effects of regulation and deregulation in goods and labor markets. Q J Econ 118(3):879–907

Bradley D, Huber E, Moller S, Nielsen F, Stephens JD (2003) Distribution and redistribution in postindustrial democracies. World Politics 55(2):193–228

Buera FJ, Monge-Naranjo A, Primiceri GE (2011) Learning the wealth of nations. Econometrica 79(1):1–45

Cabral R, García-Díaz R, Mollick AV (2016) Does globalization affect top income inequality? J Policy Model 38(5):916–940

Causa O, Hermansen M, Ruiz N (2016) The distributional impact of structural reforms

Cull R, Xu LC (2003) Who gets credit? the behavior of bureaucrats and state banks in allocating credit to chinese state-owned enterprises. J Dev Econ 71(2):533–559

Dabla-Norris, Ho G, Kyobe AJ (2016) Structural reforms and productivity growth in emerging market and developing economies. IMF Working Paper

David AC, Komatsuzaki T, Pienknagura S (2022) The macroeconomic and socioeconomic effects of structural reforms in latin america and the caribbean. Brook Pap Econ Act

David AC, Komatsuzaki T, Pienknagura S, Roldos J (2020) The macroeconomic effects of structural reforms in latin america and the caribbean. IMF Working Papers 2020(195)

De Haan J, Sturm JE (2017) Finance and income inequality: A review and new evidence. Eur J Polit Econ 50:171–195

de Haan J, Wiese R (2020) The impact of product and labour market reform on growth: Evidence for oecd countries based on local projections. J Appl Econ

Delis MD, Hasan I, Kazakis P (2014) Bank regulations and income inequality: Empirical evidence. Rev Financ 18(5):1811–1846

Driscoll JC, Kraay AC (1998) Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev Econ Stat 80(4):549–560

El Herradi M, Leroy A (2019) Monetary policy and the top one percent: Evidence from a century of modern economic history

Fournier JM, Johansson Å (2016) The effect of the size and the mix of public spending on growth and inequality

Freistein K, Mahlert B (2016) The potential for tackling inequality in the sustainable development goals. Third World Quarterly 37(12):2139–2155

Furceri D, Celik SK, Jalles JT, Koloskova K (2021) Recessions and total factor productivity: Evidence from sectoral data. Econ Model 94:130

Furceri D, Loungani MP (2015) Capital account liberalization and inequality. International Monetary Fund

Furceri D, Loungani P (2018) The distributional effects of capital account liberalization. J Dev Econ 130:127–144

Furceri D, Ostry JD (2019) Robust determinants of income inequality. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 35(3):490–517

Ghosh AR, Christofides C, Kim J, Papi L, Ramakrishnan U, Thomas A, Zalduendo J (2005) The design of IMF-supported programs, vol 241. International Monetary Fund Washington

Giuliano P, Mishra P, Spilimbergo A (2013) Democracy and reforms: evidence from a new dataset. Am Econ J Macroecon 5(4):179–204

Haggard S, Webb SB (2018) What do we know about the political economy of economic policy reform? In: Modern Political Economy and Latin America, Routledge, pp 71–80

Hamilton JD (2018) Why you should never use the hodrick-prescott filter. Rev Econ Stat 100(5):831–843

Hodrick RJ, Prescott EC (1997) Postwar us business cycles: an empirical investigation. J Money Credit Bank pp 1–16

Imai K, Ratkovic M (2014) Covariate balancing propensity score. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Stat Methodol) 76(1):243–263

Imbens GW (2004) Nonparametric estimation of average treatment effects under exogeneity: A review. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):4–29

IMF (2008) World Economic Outlook, October 2007: Globalization and Inequality. International Monetary Fund

Jaumotte F, Buitron CO (2015) Inequality and labor market institutions. imf staff discussion note. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Jordà Ò (2005) Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. Am Econ Rev 95(1):161–182

Jordà Ò, Taylor AM (2016) The time for austerity: estimating the average treatment effect of fiscal policy. Econ J 126(590):219–255

Joumard I, Pisu M (2012) Bloch D (2013) Tackling income inequality: The role of taxes and transfers. OECD Journal: Economic Studies 1:37–70

KNBS and SID (2013) Exploring Kenya’s Inequality-Pulling Apart or Pooling Together? ISBN: 978-9966-029-19-5, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and Society for International Development (SID). Nairobi, Kenya

Kose MA, Di Giovanni MJ, Faria MA, Schindler MM, Dell’Ariccia MG, Mauro MP, Ostry MJD, Terrones MM (2008) Reaping the benefits of financial globalization. International Monetary Fund

Koudalo YM, Wu J (2022) Does financial liberalization reduce income inequality? evidence from africa. Emerg Mark Rev 53:100945

Kugler AD, Pica G (2003) Effects of employment protection and product market regulations on the italian labor market. Available at SSRN 477443

Larrain M, Stumpner S (2017) Capital account liberalization and aggregate productivity: The role of firm capital allocation. J Financ 72(4):1825–1858

Li J, Yu H (2014) Income inequality and financial reform in asia: the role of human capital. Appl Econ 46(24):2920–2935

Li X, Su D (2021) Does capital account liberalization affect income inequality? Oxford Bull Econ Stat 83(2):377–410

Lim G, McNelis PD (2016) Income growth and inequality: The threshold effects of trade and financial openness. Econ Model 58:403–412

Lunceford JK, Davidian M (2004) Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: a comparative study. Stat Med 23(19):2937–2960

Mahler VA (2004) Economic globalization, domestic politics, and income inequality in the developed countries: A cross-national study. Comp Pol Stud 37(9):1025–1053

Mandel B (2010) Dependencia revisited: Financial liberalization and inequality in latin america. The Michigan Journal of Business 1001:57–96

McKinnon RI (1973) Money and capital in economic development (washington: Brookings institute)

Morelli S (2011) Economic crises and inequality. UNDP-HDRO occasional papers (2011/6)

Nguyen VB (2021) The difference in the fdi inflows-income inequality relationship between developed and developing countries. J Int Trade Econ Dev 30(8):1123–1137

Ni N, Liu Y (2019) Financial liberalization and income inequality: A meta-analysis based on cross-country studies. China Econ Rev 56:101306

Ostry MJD, Berg MA, Kothari S (2018) Growth-equity trade-offs in structural reforms. International Monetary Fund

Ostry MJD, Prati MA, Spilimbergo MA (2009) Structural reforms and economic performance in advanced and developing countries. International Monetary Fund

Ramey VA, Zubairy S (2018) Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: evidence from us historical data. J Polit Econ 126(2):850–901

Roland G (2001) Ten years after... transition and economics. IMF Staff Papers 48(Suppl 1):29–52

Ronald M (1973) Money and capital in economic development. Brookings institution, Washington DC

Rubin DB (2002) Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 2(3):169–188

Shaw ES (1973) Financial deepening in economic development. Oxford University Press, New York

Stock JH, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear iv regression. chapter 5 in: Andrews, dwk, stock, jh (eds.), identification and inference in econometric models: Essays in honor of thomas j. rothenberg

Svirydzenka K (2016) Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. International Monetary Fund

Tenreyro S, Thwaites G (2016) Pushing on a string: Us monetary policy is less powerful in recessions. Am Econ J Macroecon 8(4):43–74

UNDP (2013) Humanity divided: Confronting inequality in developing countries. UNDP

Wiese R, Jalles JT, de Haan J (2023) Structural reforms and income distribution: New evidence for OECD countries

Wooldridge JM (2007) Inverse probability weighted estimation for general missing data problems. J Econ 141(2):1281–1301

Wooldridge JM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Chris Papageorgiou for kindly sharing the database on structural reforms. I would like to express my gratitude to the editor, the associate editor, and the two anonymous reviewers for providing highly valuable feedback on previous versions of my paper. Their input has played a crucial role in shaping the final version. I would also like to thank Estel Ablam Apeti for engaging discussions and valuable comments. Additionally, I am thankful to UNU-WIDER for providing me with the opportunity to conduct this study. Special thanks are extended to Jesse Lastunen, Michael Danquah, Abrams Tagem, Nyemwererai Matshaka, and Rodrigo Oliveira for their insightful comments that significantly enriched this paper. Any remaining errors or omissions are my sole responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomado, K.M. Distributional Effects of Structural Reforms in Developing Countries: Evidence from Financial Liberalization. Open Econ Rev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-023-09740-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-023-09740-7