Abstract

We examine the link between the quality of fiscal governance and access to market-based external finance. Stronger fiscal governance is associated with improvements in several indicators of market access, including a higher likelihood of issuing sovereign bonds and having a sovereign credit rating, receiving stronger ratings, and obtaining lower spreads. Using the more granular information on quality of fiscal governance from Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) assessments for 89 emerging and developing economies, we find that similar indicators of market access are correlated with sound public financial management practices, especially those that improve budget transparency and reporting, debt management, and fiscal strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Many credit agencies include governance measures such as the World Bank’s Worlwide Governance Indicators (WGI) in their publicly-available credit rating methodologies.

Existing research highlights factors explaining the probability that a country issue external debt, the amounts borrowed, and the yields and spreads on these debts in both primary markets [e.g.,] (Kamin and Von Kleist 1999) and secondary markets (Bellas et al. 2010; Rocha and Moreira 2010; Baldacci et al. 2011; Siklos 2011; Comelli 2012; Kennedy and Palerm 2014; Csontó 2014; Guscina et al. 2014). Other papers examine idiosyncratic differences that are region-specific or arise because of first-time bond issuances (Olabisi and Stein 2015; Gueye and Sy 2014). These factors can all be interpreted as increasing or mitigating risk and hence impacting the required return of investors.

Kennedy and Palerm (2014) argues that virtually all of the run-up in emerging market spreads during the 2008-09 financial crisis was due to a large increase in the measure of risk aversion.

Glennerster and Shin (2008) exploit random variation in the timing of introduction of improved IMF country reports, ROSC assessments and Special Data Dissemination Standard (SDDS) data releases across countries. They find that an improvement in fiscal transparency linked to these reforms lowered average sovereign bond yields across 23 emerging market economies.

Arndt and Oman (2006), Knack (2006), Kurtz and Schrank (2007) and Thomas (2010) question the usefulness of the WGI for making comparisons of governance over time and across countries since they are normalized within every year. These authors also call out possible biases in the inputs underlying the aggregate governance indicators, including the lack of independence of some of the assessments. Kaufmann et al. (2010) argue that these concerns are not specific to the WGI and are likely to arise in the context of any effort to measure governance.

The other WGI indicators are voice and accountability; political stability; regulatory quality; rule of law; and control of corruption.

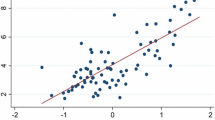

Since the inputs to the WGI are sometimes subjective or prone to measurement error, Charron et al. (2010) suggest that countries should be clustered with respect to their relative quality of governance. The binned scatterplots achieve this by computing the average outcome within deciles of the Government Effectiveness score. In the appendix, we also show that the results are robust to using alternative measures of fiscal governance, such as the WGI Rule of Law or Control of Corruption scores (See Figs. 6 and 7)

Many of these countries may be rated by export credit agencies, insurance agencies, and international banks, but these ratings are often confidential or for internal use only.

Ratha et al. (2011) examine the role of macroeconomic, fiscal and governance variables as predictors of sovereign credit ratings. However, they focus on rule of law, rather than government effectiveness.

The impact of fiscal governance on market access may be different in countries with large fiscal deficits or public debt. For example, a large fiscal deficit may be less of a concern in a country with a strong record of fiscal transparency. To account for these nonlinearities, we also considered controlling for interactions between fiscal governance and fiscal deficits and debt ratios. The results are similar, and are available upon request.

Since the regression of average ratings on the WGI score is conditional on having a credit rating, we have also considered two-step estimators as in Heckman (1979), which considers the possible selection bias of excluding unrated countries. The results are similar and are available upon request.

As Fig. 3 in the appendix shows, PEFA scores are strongly correlated with the WGI Government Effectiveness score.

See PEFA (2016). This format reflects the 2016 PEFA framework. The previous 2005 and 2011 PEFA frameworks had slightly different questions and structure, which we map into the 2016 framework to ensure consistent scores across assessments.

One important limitation of our analysis is the potential for spatial dependence in financial market access. Access to markets and financial market conditions tend to cluster by geographic region, and it is common to observe financial market shocks in one country (e.g., to sovereign spreads) spill over to neighboring countries. Even when spatial dependence does not impact the unbiasedness and consistency of the pooled OLS estimator, it can still impact the estimated standard errors [e.g.,] (Wooldridge 2002),.

No countries in our sample achieved an A score in the budget execution and external audit categories, so those coefficients could not be estimated and were dropped from the analysis.

As in the previous section, the impact on the average credit rating is estimated conditional on having a credit rating. Results from a two-step estimator that controls for possible selection bias of excluding unrated countries are qualitatively similar, and available upon request.

References

Alesina A, Perotti R (1999) Budget deficits and budget institutions. In: Poterba JM, von Hagen J (eds) Fiscal Institutions and Fiscal Performance, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, chap 1, pp 13–36

Alt JE, Lassen DD (2006) Fiscal transparency, political parties, and debt in oecd countries. Eur Econ Rev 50(6):1403–1439

Anselin L (1988) Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models, vol 4. Springer, Netherlands

Arbatli E, Escolano J (2012) Fiscal transparency, fiscal performance and credit ratings. IMF Working Paper (12/156)

Arndt C, Oman C (2006) Uses and abuses of governance indicators. Development Centre Studies OECD Publishing

Baldacci E, Gupta S, Mati A (2011) Political and fiscal risk determinants of sovereign spreads in emerging markets. Rev Dev Econ 15(2):251–263

Bellas D, Papaioannou M, Petrova I (2010) Determinants of emerging market sovereign bond spreads: Fundamentals vs financial stress. IMF Working Paper (10/281)

Bermeo SB (2017) Aid allocation and targeted development in an increasingly connected world. Int Organ 71(Fall):735–766

Biglaiser G, Staats JL (2012) Finding the democratic advantage in sovereign bond ratings: The importance of strong courts, property rights protection, and the rule of law. Int Org 66(3):515–535

Bodea C, Hicks R (2018) The use of corruption indicators in sovereign ratings. Econ Politics 30:340–365

Brown M, Sienaert A (2019) Governance improvements and sovereign financing costs in developing countries. MTI discussion paper World Bank, Washington, DC, p 14

Charron N, Lapuente V, Rothstein B (2010) Measuring the quality of government and subnational variation

Comelli F (2012) Emerging market sovereign bond spreads: Estimation and back-testing. Emerg Mark Rev 13(4):598–625

Coulibaly BS, Gandhi D, Senbet LW (2019) Is sub-saharan africa facing another systemic sovereign debt crisis? Brookings Institution

Csontó B (2014) Emerging market sovereign bond spreads and shifts in global market sentiment. Emerg Mark Rev 20:58–74

Eichengreen B, Mody A (1998) What explains changing spreads on emerging-market debt: Fundamentals or market sentiment? NBER Working Paper (w6408)

Gelos RG, Sahay R, Sandleris G (2011) Sovereign borrowing by developing countries: What determines market access? J Int Econ 83(2):243–254

Glennerster R, Shin Y (2008) Does transparency pay? IMF Staff Papers 55(1)

Gollwitzer S, Kvintradze E, Prakash T, Zanna LF, Dabla-Norris E, Allen RI, Yackovlev I, Lledo VD (2010) Budget institutions and fiscal performance in low-income countries. IMF Working Paper (10/80)

Gueye CA, Sy AN (2014) Beyond aid: how much should african countries pay to borrow? J Afr Econ 24(3):352–366

Guscina A, Pedras GB, Presciuttini G (2014) First-time international bond issuance - new opportunities and emerging risks. IMF Working Paper (14/127)

Hameed F (2005) Fiscal transparency and economic outcomes. IMF Working Paper (05/225)

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica pp 153–161

IMF (2012) Fiscal transparency, accountability, and risk. IMF Policy Paper pp 1–54

IMF (2018a) Fiscal Transparency Handbook. International Monetary Fund

IMF (2018b) Review of 1997 guidance note on governance - a proposed framework for enhanced fund engagement. IMF Policy Paper

IMF (2019a) Fiscal Monitor: Curbing Corruption. International Monetary Fund

IMF (2019b) Sub-saharan africa regional economic outlook (april 2019): Recovery amid elevated uncertainty. International Monetary Fund

Irwin TC (2012) Accounting devices and fiscal illusions. IMF Staff Discussion Note (12/02)

Kamin SB, Von Kleist K (1999) The evolution and determinants of emerging markets credit spreads in the 1990s. BIS Working Paper (68)

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2010) The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (5430)

Kennedy M, Palerm A (2014) Emerging market bond spreads: The role of global and domestic factors from 2002 to 2011. J Int Money Financ 43:70–87

Knack S (2006) Measuring corruption in eastern europe and central asia: A critique of the cross-country indicators. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (3968)

Kurtz MJ, Schrank A (2007) Growth and governance: Models, measures, and mechanisms. J Pol 69(2):538–554

Olabisi M, Stein H (2015) Sovereign bond issues: Do african countries pay more to borrow? J Af Trade 2(1–2):87–109

Panizza U (2017) The use of corruption indicators in sovereign ratings. IDB Working Paper

PEFA (2016) Framework for assessing public financial management. Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability Secretariat, Washington, DC

Persson T, Tabellini G (2004) Constitutional rules and fiscal policy outcomes. Am Econ Rev 94:25–46

Presbitero AF, Ghura D, Adedeji OS, Njie L (2016) Sovereign bonds in developing countries: Drivers of issuance and spreads. Rev Dev Finance 6(1):1–15

Ratha D, De PK, Mohapatra S (2011) Shadow sovereign ratings for unrated developing countries. World Dev 39(3):295–307

Rocha K, Moreira A (2010) The role of domestic fundamentals on the economic vulnerability of emerging markets. Emerg Mark Rev 11(2):173–182

Siklos PL (2011) Emerging market yield spreads: Domestic, external determinants, and volatility spillovers. Glob Financ J 22(2):83–100

Thomas MA (2010) What do the worldwide governance indicators measure? Euro J Dev Res 22(1):31–54

Weber A (2012) Stock-flow adjustments and fiscal transparency: A cross-country comparison. IMF Working Paper (12/39)

Wooldridge JM (2002) Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank Philip Barrett, Racheeda Boukezia, Sophia Chen, Jason Harris, Ashraf Khan, Jason Lakin, Paolo de Renzio, two anonymous reviewers and seminar participants at the IMF and World Bank for helpful comments and discussions. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

Appendices

Other Figures

Government Effectiveness and Share of External Public Debt that is Market-Based. Noted: The left panel examines the relation between the share of public external debt that was market-based in 2010 (e.g., sovereign bond issuances or syndicated loans) and the WGI Government Effectiveness score. The right panel shows the impact of PEFA score improvements on the same indicator. In both cases, the sample is restricted to emerging and developing economies

Rule of Law and Market Access. Note: These binned scatterplots display the nonparametric relation between fiscal governance, measured by the WGI Rule of Law score (horizontal axes), and different indicators of access to market-based external finance (vertical axes). Fitted quadratic regression lines are shown in red. The top left panel shows whether a country was rated by any of the three major rating agencies in 2010, while the top right panel looks at the average sovereign rating in 2010, for countries that did have a rating (the vertical axis follows the Standard & Poor’s rating scale). The bottom left panel examines whether a country issued at least one external sovereign bond between 1996 and 2016, focusing only on developing and emerging economies, while the bottom right panel plots the (option-adjusted) spread for countries that issued sovereign bonds

Control of Corruption and Market Access. Note: These binned scatterplots display the nonparametric relation between fiscal governance, measured by the WGI Control of Corruption score (horizontal axes), and different indicators of access to market-based external finance (vertical axes). Fitted quadratic regression lines are shown in red. The top left panel shows whether a country was rated by any of the three major rating agencies in 2010, while the top right panel looks at the average sovereign rating in 2010, for countries that did have a rating (the vertical axis follows the Standard & Poor’s rating scale). The bottom left panel examines whether a country issued at least one external sovereign bond between 1996 and 2016, focusing only on developing and emerging economies, while the bottom right panel plots the (option-adjusted) spread for countries that issued sovereign bonds

Other Tables

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keita, K., Leon, G. & Lima, F. Do Financial Markets Value Quality of Fiscal Governance?. Open Econ Rev 32, 907–931 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-021-09652-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-021-09652-4